The Evolution of the Golf Course at Augusta National: What Would The Good Doctor Say?

by

Daniel Wexler

March 2011

It is a true paradox in the world of golf course design.

Consider the game’s two most famous layouts, the Old Course at St. Andrews and the Augusta National Golf Club. The former is a product primarily of nature and a timeless, almost mystical evolution – as though whatever cosmic forces govern such things have gently massaged the landscape (with a little help from Alan Robertson) over the course of several centuries. The latter, conversely, ranks among the most carefully planned layouts of all time, its creators – the legendary Bobby Jones and Dr. Alister MacKenzie – building it as the embodiment of a clearly articulated set of cutting-edge design principles. Yet as the game has changed immeasurably over the last 110 years, St. Andrews, a golf course “built” with virtually no plan whatsoever, has remained largely constant. Augusta, on the other hand, a layout based on the strictest of concepts, has been altered nearly beyond description.

Go figure.

But Augusta, after all, is not your local neighborhood golf course; indeed, it is not even your standard, run-of-the-mill, Major championship venue. By hosting The Masters every peacetime April since 1934, it has inevitably been subject to the sort of nipping and tucking that generally takes place perhaps once a decade (when a U.S. Open or PGA Championship visits) at places like Winged Foot, Oakmont or Pebble Beach. But at Augusta, well-intended ideas to improve the golf course seldom are tempered by several years worth of study and debate; with the next Major never more than 12 months away, they happen quickly and, in the contemporary era, with almost numbing regularity.

The purpose of this piece is to examine, on a hole-by-hole basis, the full scope of these changes, and to reach some conclusions as to how Jones and MacKenzie’s original 1933 design might measure up against the layout shortly to be on display once again at the 2009 Masters. In order to do this, however, we must first consider just what Jones and MacKenzie had in mind back in the beginning, for their approach was among the most revolutionary in the history of golf design.

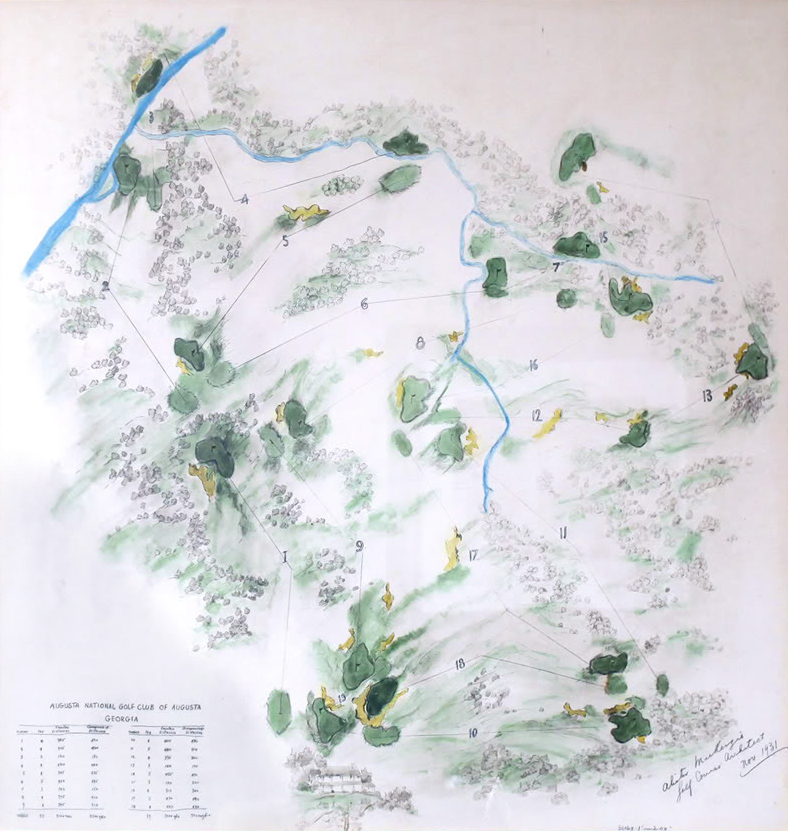

1930 – Four years before completion. (Note Magnolia Lane on the far right about a third of the way down)

Both Bobby Jones, 13-time Major champion and the greatest amateur golfer of all-time, and Dr. Alister MacKenzie, frequently considered the greatest course designer in history, believed in creating strategic holes whose challenge was as much mental as physical, with multiple angles of play generally allowing golfers of all abilities a chance to effectively navigate their way along. To accomplish this, they built Augusta with uniquely wide fairways so wide, in fact, that for the great majority of its history, the club was devoid of appreciable rough altogether. As a countermeasure to this apparent generosity, green complexes were intended to be especially challenging, the often severe contouring of the putting surfaces allowing for some demanding tournament pin positions and, more importantly, greatly favoring approach shots played from specific places. Thus a fairway might measure a full 60 yards in width, but only the player skilled enough to position their tee ball within, say, a particular 10-yard section (generally far right or left) would be rewarded with an ideal angle from which to attack. Those less skilled might still be approaching from the fairway, but generally from angles where the greens hazards, elevation and/or contouring would repel all but the a perfectly struck shot.

MacKenzie, of course, was well-known for his green contouring, but it is unlikely that many of his roughly 120 courses worldwide were constructed with putting surfaces as consistently undulating as those at Augusta. The great majority of these have since been altered, but not without reason, for if the contouring of Augusta’s original greens was anywhere near as severe as both MacKenzie’s sketches and early written descriptions indicate, the more demanding ones would have been largely unplayable under agronomical conditions circa 1990, never mind with profligate 12+ stimpmeter readings regularly achieved today. And it would appear that these potential problems were not lost on Bobby Jones and his right hand man (and longtime club operations majordomo) Clifford Roberts from the very beginning, for several of the more dramatic putting surfaces were softened considerably by one-time MacKenzie partner Perry Maxwell before the close of the 1930’s. The club was acting ahead of the curve by making such early changes, but there can be no doubt that agronomical advances would have eventually mandated most such alterations, regardless.

And one more largely forgotten point: Given Bobby Jones’s love of St. Andrews, and Dr. MacKenzie’s status as a former consulting architect to the Royal & Ancient Golf Club, the influence of the great Scottish links upon Augusta’s design was inevitable. But unlike so many American courses which have turned “Links Golf” into the most meaningless marketing phrase since that old 1970’s favorite, “PGA Championship Course,” Augusta actually made good, initially featuring at least seven greens (including the 1st, 3rd, 5th, 6th, 7th, 14th and 17th) upon which the run-up was the favored method of approach, and no less than nine holes which MacKenzie cited as bearing specific characteristics of famous British holes, with several being nearly direct replicas.

Augusta was also unique in one more prominent way: By relying on its green contouring to dictate ideal angles of approach, the need for the large-scale use of bunkering was minimized. Thus quite remarkably, on the day of its 1933 opening, Jones & MacKenzie’s layout, a design capable of making the player think on virtually every shot, included only 22 bunkers – or exactly half the number in play today. Further, fully nine of its 14 non-par 3s offered no sand along their generous fairways, and an impressive four holes (the 7th, 11th, 15th and 17th) included no bunkers whatsoever. Toss in the fact that water materially affected play on only five holes and the original Augusta National genuinely was the living embodiment of what today’s architects reflexively regurgitate as their “design philosophy”: a course capable of testing the greatest golfers on earth, yet also one which, with an absence of massive hazards and life-or-death carries, was truly manageable for the less-skilled player willing to put a little thought into their work.

But that was then, and this is now.

Beyond the long-forgotten fact that the nines were originally played in reverse order (the change was made in 1934 after the occasional Amen Corner frost delayed early rounds) today’s Augusta is a vastly different golf course. The roster of architects who have performed alterations – both minor and, occasionally, quite major – is led by the aforementioned Perry Maxwell (who modified or added a total of seven greens during the late 1930’s), Robert Trent Jones (significant changes to several holes), George Cobb (who performed all manor of alterations, large and small, throughout the 1960’s and ‘70s) and, most recently, Tom Fazio, but many more chefs (included several Masters champions) have added ingredients to this broth. The net result is a golf course which still retains roughly 90% of its original routing – but, with the addition of rough, the planting of trees, the alteration of nearly every green complex and sundry other changes, is, by any definition, a far cry from Jones and MacKenzie’s utterly unique original.

Just how different? With the understanding that more tiny nips and tucks have taken place than can be comprehensively cataloged, let’s take a hole-by-hole look at the layout’s most significant alterations, and how, over the decades, they have affected play.

Hole No. 1 – Tea Olive Par 4 1933: 400 yards 2009: 455 yards

Augusta’s famed opening par 4 – site of so many ceremonial tee shots by Jock Hutchison, Fred McLeod, Byron Nelson and Sam Snead – has undergone its fair share of alteration over the decades, though an argument can be made that at least in terms of playing angles, it still approximates Jones & MacKenzie’s strategic concept to a reasonable degree. Initially featuring the first of an original eight bunkerless greens, the opener was designed to encourage a run-up approach, though the precise configuration of the elevated putting surface (which included a protruding front-left section) made such a play considerably easier from the right side of the fairway. The most prominent single alteration was the replacement of this extended section of green with a bunker in 1951, which has limited the great majority of approaches (and certainly any played from the left two-thirds of the fairway) to the aerial route ever since. Of course, this hazard also served – at least cosmetically – to enhance the right third of the fairway’s “optimum” status, which in turn placed a greater emphasis on the large right-side fairway bunker, an invasive hazard which has existed since 1933, but which has been moved and/or expanded multiple times since World War II.

An additional change has substantially altered the holes aesthetics but done little to affect the play of the competent ball-striker: the removal of a large, impressively shaped MacKenzie bunker that sat just off the fairways left edge, some 50 yards shy of the green. Were it still in existence, this hazard would surely draw parallels to the huge, wildly shaped bunker that sits in a similar no-mans land along the 10th fairway though as we shall soon see, that bunker initially served rather a different purpose. Number one’s deceased hazard, in contrast, could never have factored very much into play for all but the weakest of golfers.

That the hole has been lengthened some 55 yards (by extending the tee backwards, onto land originally occupied by the putting green) represents at best a push in the courses battle to defend itself against modern equipment, though the deeper tees have certainly helped maintain the fairway bunkers continuing relevance in this era of unchecked technology.

Better Then or Now?

A fairly strong argument can be made that for all classes of players, the exchange of the old no-mans-land fairway bunker for the greenside hazard was a good one. True, Jones and MacKenzie’s favored run-up approach shot largely disappeared, but the move injected number one with a new strategic component, truly making the right fairway bunker the focal point and the subsequent decision whether to attempt to carry it or bail out left a fine strategic proposition. In this light, the tinkering with the bunkers size and position though anathema to purists has certainly served to strengthen the hole as well.

Hole No. 2 – Pink Dogwood Par 5 1933: 525 yards 2009: 575 yards

The par-5 second has grown 50 yards in 75 years, with the tee initially being moved back during the World War II era, then back and right in 1977, and ultimately even further back in 1999. However, the degree to which the hole has changed greatly exceeds simple size. Always a sharply downhill dogleg left that afforded the better player an opportunity to get home in two, it initially featured a near-L-shaped green bending left-to-right around a single deep bunker. This configuration naturally favored a second shot played from the far left side of the fairway an area made harder to access off the tee by Jones and MacKenzie’s placement of a vast, left-side carry bunker, and by the tree-lined turn of the dogleg.

Change initially came in 1946, when a bunker was added to the greens front-left edge, and in 1953 the putting surface itself was extended back and to the left, creating the near-triangular configuration still in play today. By 1966, the left-hand fairway bunker – long since obsolete for better players was filled in, but not replaced by a new left-side bunker further downrange. Instead, at the suggestion of Gene Sarazen, a right-side hazard was added, theoretically narrowing the primary driving area but also leaving the shorter left-side route more open for attack. This newer right-side bunker has been altered/expanded since, most recently being enlarged in 1999.

It is also interesting to note that MacKenzie’s original 1931 routing map indicates plans for a creek to cross in front of the second green. This same small hazard which was an extension of the creek-turned-pond which fronts the fifteenth green – was also slated to cross the first, third, seventh, eighth and seventeenth fairways, though generally in far less invasive ways. For the most part, however, this creek was piped underground during construction, though at the first and seventeenth, it remained in front of the tees until 1951, when it was finally buried in its entirety.

Better Then or Now?

The range of shotmaking skills originally required for the better player to reach the second green in two was enviable: a drawn tee ball (to carry/avoid the bunker, and follow the general turn of the fairway), then a long, controlled fade to the narrow, left-to-right bending green. Todays re-shaped putting surface, however, is a bit more neutral in which angle of approach it favors, varying daily with potential far-left and far-right pin placements. On the one hand, this can be viewed as more strategic – that is, one might be inclined to flirt with the fairway bunker to open up a back-left pin one day, then skirt the treeline to get a better angle on a back-right target the next. But on a hole of this size, where distance off the tee is a primary consideration, the fact that the bunker guards the longer (and thus generally less-desirable) right side seems a bit out-of-balance. Advantage: 1933 but only just.

Hole No. 3 – Flowering Peach Par 4 1933: 350 yards 2009: 350 yards

The range of shotmaking skills originally required for the better player to reach the second green in two was enviable: a drawn tee ball (to carry/avoid the bunker, and follow the general turn of the fairway), then a long, controlled fade to the narrow, left-to-right bending green. Today’s re-shaped putting surface, however, is a bit more neutral in which angle of approach it favors, varying daily with potential far-left and far-right pin placements. On the one hand, this can be viewed as more strategic – that is, one might be inclined to flirt with the fairway bunker to open up a back-left pin one day, then skirt the treeline to get a better angle on a back-right target the next. But on a hole of this size, where distance off the tee is a primary consideration, the fact that the bunker guards the longer (and thus generally less-desirable) right side seems a bit out-of-balance. Advantage: 1933 – but only just.

The third green was the first of the seven altered by Perry Maxwell, the sum of his work apparently being the shaving of some front-right putting surface and, perhaps, some reduction in overall contour. Beyond this, the lone obvious alteration was Jack Nicklaus’s 1982 division/expansion of a large, left-side fairway bunker into four smaller ones (thus creating an aesthetic anomaly on a course otherwise devoid of such clusters) and adding some adjacent mounds. It is also worth noting that the tee was moved slightly right in 1953 and has twice been modestly lengthened – a curious development given that the hole is listed at the same yardage today as it was in 1933. This suggests that the third was one of several holes (including the fourth, the thirteenth and the original sixteenth) that did not measure up completely to their listed opening-day yardages – though with modern measuring techniques, its current 350-yards can be taken to the bank.

Better Then or Now?

Is there a major difference? Today’s golfer can obviously place the tee ball much closer to the green, but smarter ones likely won’t, preferring to leave themselves a full wedge approach rather than a dicey three-quarter (or less) pitch. Further, the golfing world has really only known the post-Maxwell green (his work was done in 1937), and Nicklaus’s bunker work is, for the better player anyway, more cosmetic than invasive. The argument could perhaps be made that in today’s game, moving the tees forward might induce Masters participants to try and drive the green (as Tiger Woods did, leading to a memorable double-bogey six, in 2003) but that’s far more a function of evolving technology than any changes to the hole’s design.

Hole No. 4 – Flowering Crab Apple Par 3 1933: 190 yards 2009: 240 yards

The long par-3 fourth is the first of two front nine one-shotters to have begun life bearing more than a passing resemblance to a famous Old Country standard, in this case the Eden eleventh (more properly known as High In) at St. Andrews. During the club’s much-chronicled construction, Jones was careful to point out that Augusta’s holes would only demonstrate certain salient qualities of these great British holes and not include straight, Charles Blair Macdonald-like replicas. But the fourth (of which MacKenzie observed “we may have constructed a hole that will compare favorably with the original”) was clearly an exception. Like the hallowed original, MacKenzie’s replica featured a pair of fronting bunkers modeled after the legendary Hill and Strath, as well as a green with so much back-to-front slope that the Doctor’s own sketches indicate an eight-foot rise from front apron to back collar. The original green was also more of the boomerang variety (a MacKenzie favorite), but rotated slightly counter-clockwise – unquestionably a significant difference from the original Eden. Additionally, early photos indicate the finger of putting surface which extended forward, between the two bunkers, to be extraordinarily narrow, with several yards of grass separating it from the sand on either side. Clearly unpinable, and not a feature of either the original Eden or any C.B. Macdonald/Seth Raynor replicas, the purpose of this idiosyncrasy will forever remain a mystery.

Perry Maxwell rebuilt the fourth green in 1938, diminishing its pitch and turning it more towards the 90-degree, L-shaped configuration of the present. Further, the hole has twice been lengthened since World War II, though only in recent years did its back tee reach (and ultimately exceed) the 220-yard distance that has been listed since the early postwar years. Today, the hole stands a stout 50 yards longer than in its youth.

Better Then or Now?

A great question. Today’s hole is an entirely different beast from the Eden redux of yesteryear, playing far longer, to a green of different shape and contour. But… Since MacKenzie’s original, severely sloped putting surface would have been largely unplayable in the face of modern green speeds anyway, how much can we complain?

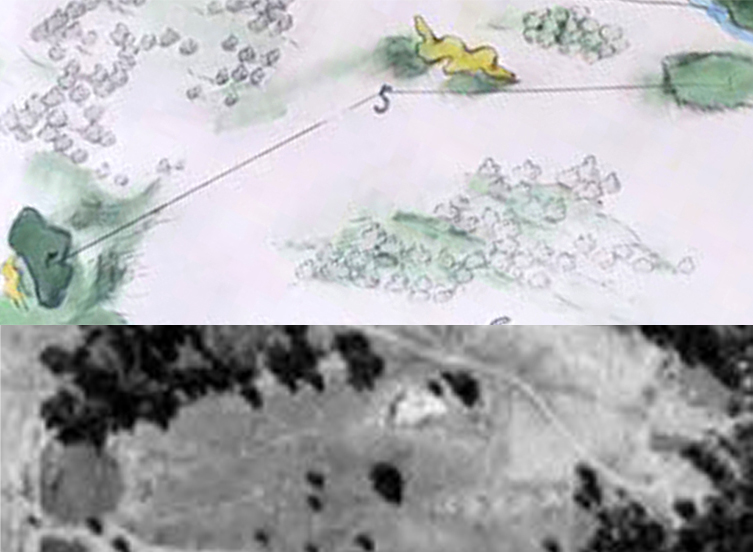

Hole No. 5 – Magnolia Par 4 1933: 435 yards 2009: 455 yards

The demanding par-4 fifth was, by MacKenzie’s own explanation, “a similar type of hole to the famous seventeenth, the Road Hole at St. Andrews” – this despite the absence of a road, railroad sheds, an Old Course Hotel, or any sort of fronting bunker whatsoever. But regardless of such glaring stylistic differences, the substance of the hole remains among the least-altered at Augusta, particularly the putting surface which, save for some adjacent mounding added during the 1950’s and ‘60s, has been little bothered. Despite a left-side fairway bunker being plainly apparent in MacKenzie’s plans, the fifth began life absent any man-made hazards. A single, rear bunker was added sometime after opening (its creation is sometimes dated to 1956, but it is clearly visible in prewar aerial photos) though it surely represented more of a charitable donation than an added danger, for it prevents overly aggressive shots from tumbling even further down a rear hillside.

A more visible change was the early addition of two left-side fairway bunkers, which, through frequent revision, fluctuated between being one large hazard or two smaller ones for many years. However, despite Bobby Jones citing them in his 1959 book Golf Is My Game as central to the hole’s challenge (“The proper line here is, as closely as possible, past the bunker on the left side of the fairway…”), they served primarily as little more than directional aids, for better players had little trouble carrying drives comfortably past them. They became far more significant in 2003, however, when, as a part of a Tom Fazio project to enhance the fairway’s dogleg, they were reconstructed far downrange (they are now a 310-yard carry) and placed at a more invasive angle.

Better Then or Now?

Not too terribly different, really. Adjusted for technology, the hole is certainly shorter (the back tee is flush against Berckmans Road, and thus offers no room for expansion) but the fairway bunkers are rather more in play. A demanding two-shotter then, a demanding two-shotter now.

Hole No. 6 – Juniper Par 3 1933: 180 yards 2009: 180 yards

In contrast to number five, the Old Country roots of the par-3 sixth were rather more apparent on opening day, for the sixth was modeled after the famous Redan at North Berwick, the game’s most copied hole. With typical modesty, MacKenzie referred to this version as “a much more attractive hole than the original,” and it did offer several prominent differences. First, whereas North Berwick’s Redan is played semi-blind over a short rise in its fairway, Augusta’s rendition is played downhill, affording a much greater sense of the hole’s angles and challenges. Second, while the original (and its legion of replicas) features a putting surface which falls away from front-right to back-left, MacKenzie’s sketch suggests that the sixth fell more sideways, into a left/front-left quadrant. Further, though not apparent in the sketch, it is widely reported that this green originally had a prominent mound very near its center – a hillock steep enough that golfers would be hard-pressed to maintain control of their ball if forced to putt over it.

In this light, it is hardly surprising that the sixth green was among Perry Maxwell’s initial 1937 renovations, a reconstruction that removed the mound, left much of the Redan-like left-side contour intact, and added a prominent right-side shelf. Also, a small creek, which sat in the valley some 75 yards shy of the green (and which was at one time dammed into a pond) was permanently buried in 1959.

Better Then or Now?

As with hole number four, modern green speeds would have surely rendered MacKenzie’s original green unplayable at least two decades ago, so the debate is largely a moot one. Still, the slightly modified Redan concept is alive and well in the putting surface’s front-left section, and the elevated right side represents a completely different strategic element – so if nothing else, it’s hard to seriously argue that the hole has gotten worse.

Hole No. 7 – Pampas Par 4 1933: 340 yards 2009: 445 yards

Few holes at Augusta National have been altered to the extent that the par-4 seventh has; indeed, aside from remaining in its original playing corridor, it is today an entirely different hole from that which Jones and MacKenzie created in 1933. Their original was a bunkerless drive-and-pitch modeled after the 18th at St. Andrews, running straight away and culminating in a shallow, three-tiered green with a prominent front-right finger, and a Valley of Sin-like depression guarding the front-left. Deemed too easy early in life, it was soon replaced by a “Postage Stamp” concept reportedly suggested by Horton Smith; that is, the small, somewhat elevated, and closely guarded putting surface which Perry Maxwell constructed on a rise behind the original green site in 1938. This comparably shallow target was initially fronted by the same three bunkers that remain before it today, with the back two bunkers only being added much later, in 1951.

By the new millennium, however, the club deemed that version too easy as well, leading Tom Fazio to extend the hole to 445 yards and narrow its fairway with the addition of both trees and rough. The result, while undeniably challenging, now bears zero resemblance to the Jones and MacKenzie original. It is, however, at least partially defendable if one accepts the notion that Jones’s word represents the Augusta gospel, for he clearly endorsed the narrowing concept (at least if accomplished via flora) back in 1959, when he wrote: “The tee shot on this hole becomes tighter year by year as the pine trees on either side of the fairway continue to spread. Length is not a premium here, but the narrow fairway seems to have an added impact because it suddenly confronts the player when he has become accustomed to the broad expanses of the preceding holes.”

But that said, the present version easily draws more (and louder) negative Masters comments than any hole at Augusta.

Better Then or Now?

For whom? While members might well enjoy the subtle challenges of the seventh hole circa 1933, with modern technology it would scarcely even be considered a par 4 for Masters competitors, who would drive indiscriminately towards the green and, at worst, hope for two-putt birdies from the Valley of Sin. The pre-Fazio postage stamp version, on the other hand, was still manageable for the members and quirky/fun for the pros. The present version is simply brutal unless one favors the sort of stilted, hit-it-here-or-else style of play incumbent to a modern U.S. Open, in which case we have a winner.

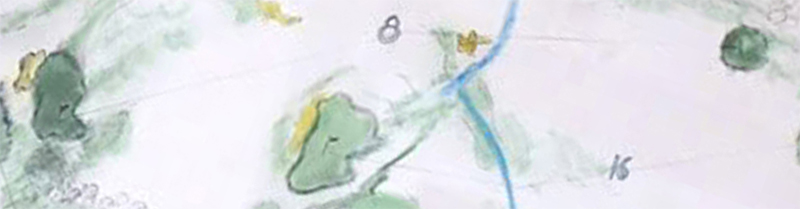

Hole No. 8 – Yellow Jasmine Par 5 1933: 500 yards 2009: 570 yards

The uphill par-5 eighth has traveled a lot of miles in its 75 years of existence, with its ruin-it-then-fix-it-again evolution representing the closest thing to a genuine architectural fiasco that Augusta National has ever had to endure. Originally built with a uniquely bunkerless, mound-flanked green similar to that in play today, the eighth was emasculated in 1956 when, concerned over spectator viewing and congestion, the club had George Cobb build a new, moundless putting surface which would eventually come to be guarded by bland, strategically insignificant bunkers. The failings of this concept were trumpeted far and wide (including, we are told, by Bobby Jones just as the project was getting started), ultimately resulting in the hiring of Byron Nelson and Joe Finger to rebuild the original green complex, complete with restored mounds and a back left quadrant nearly invisible from the front edge, in 1979.

Inasmuch as the present green can thus be considered “original,” the primary remaining alteration lies in the fairway bunker, which initially was a prominent, centerline hazard before being moved rightward in 1958, then enlarged and relocated once more by Tom Fazio in 2002. And the precise positioning of this hazard is key, for as Bobby Jones noted shortly after its initial move: “It is important that the ball be kept a bit to the right of center of the fairway… Should [the golfer] play left to avoid the bunker, the player must skirt the trees on the left with his second shot in order to get very near the green.”

During his 2002 work, Fazio also added a tee in close proximity to the 17th green, extending to 570 yards what began life as a semi-reachable 500-yarder upon which those trying to get home in two will, to quote Dr. MacKenzie, “be able to define the position of the green owing to the size of the surrounding hillock.”

Good thing they brought it back.

Better Then or Now?

Theoretically, save for the moving of the old centerline bunker, the present eighth plays very much like the original, with the additional 70 yards of length helping to retain the go-for-it-or-not balance of the 1933 version. Though the present, quite fascinating putting surface is not truly Jones and MacKenzie’s, it can still be said with reasonable fairness that this, the hole which has seen the most glaring desecration in Augusta’s design history, today plays as close to its original form as nearly any on the golf course.

Hole No. 9 – Carolina Cherry Par 4 1933: 420 yards 2009: 460 yards

Dr. MacKenzie described the par-4 ninth as being “of the Cape type” which, loosely translated, describes a hole with green jutting prominently in one direction, its often-elevated edges closely guarded by hazards. The description is an interesting one because while the initial ninth green did extend leftward above a large bunker, the putting surface itself was a classic MacKenzie boomerang, its two nearly symmetrical “wings” wrapped around the single, artistically shaped sand hazard. Given the famously uphill nature of the approach, this was a most distinctive green complex indeed, yet the club once again assigned Perry Maxwell the late-1930’s task of rebuilding it, resulting in the angled, three-tiered putting surface in play today. Maxwell’s initial version, by the way, featured four left greenside bunkers, but the two that have survived would likely be the only ones relevant to modern Masters participants.

An additional aspect of playing number nine has always been the downhill tee shot, for at the hole’s original 420-yard length, only longer hitters were capable of consistently driving more than 300 yards to the flat ground at the bottom, thus avoiding having to play so intimidating an approach – over a huge false front, no less – from a downhill lie. The hole was lengthened to 440 yards in 1973 and 460 in the new millennium, meaning that even though the bottom is more frequently driven today, the 340 yards necessary to reach it means that a missed tee ball can still result in a very dicey second.

Also noteworthy was the 2002 addition of trees and rough down the right side of the landing area, an attempt at minimizing the longer hitter’s ability to simply bomb it down the preferred side without a care in the world. At a glance, this might be decried as removing a strategic option – but an equally valid argument might be made that in this era of unchecked equipment, injecting some measure of accountability in this particular location was important in retaining the hole’s fundamental balance of play.

Better Then or Now?

This is largely a question of taste. The present three-level green, with its enormous back-to-front fall, requires the deftest of touches on both approaches and chips, and inevitably provides those tragic moments when a second shot, apparently well-struck, spins back just a yard too far…then agonizingly trickles some thirty yards back off the putting surface. MacKenzie’s original green, on the other hand, still featured the false front along its front-right edge (by most accounts, it was even more pronounced than at present), but also offered numerous exciting pin positions all around the boomerang. On balance, such was surely the more unique, invigorating configuration – but the present one hardly lacks for drama either.

Hole No. 10 – Camellia Par 4 1933: 430 yards 2009: 495 yards

Originally conceived as the layout’s opening hole, the par-4 10th opened for play as a highly strategic downhill test played to a green situated some 45-50 yards shy of the present putting surface, just to the right of the sprawling (if largely vestigal) MacKenzie bunker that famously fills the fairway today. The beauty of this configuration was that it significantly rewarded the player capable of hitting a controlled tee shot to the higher right side of the fairway, for their ensuing approach was a simple, unimpeded short iron into the heart of the crescent-shaped green. The golfer whose ball bounded indiscriminately down to the fairway’s leftward reaches, on the other hand, then faced, in MacKenzie’s words, “a difficult second shot over a large spectacular bunker, with small chance of getting near the pin” – for the green would indeed have become a very shallow, sand-fronted target from that angle.

Perhaps because it was soon being judged as a mid-round hole instead of kinder, gentler opener (indeed, MacKenzie initially described it as “a comparatively easy downhill hole”), the tenth was deemed not to be challenging enough soon after opening, prompting Perry Maxwell to build the present, longer green in 1937. Well into the postwar era, the right-front was guarded by a pair of bunkers, but the present hazard was enlarged in 1968, while the smaller “pothole” bunker located just to its right disappeared.

Other changes have been limited primarily to the teeing ground, which has been moved and elevated on multiple occasions, enhancing both the hole’s length and the angle of its dogleg.

Better Then or Now?

Once again, the operative question is: for whom? The present bigger, tougher tenth is clearly better suited to tournament competition than the hole’s initial incarnation – by a wide margin. Indeed, the longer approach – which must carry the fronting hillside, yet stop below the hole, and not be missed right (sand) or left (another steep hillside) – might be considered inspirational simply in its challenge. But the original version was considerably more strategic and, for anyone above a single-digit handicap, surely more fun. So do we judge by four days in April, or the rest of the club’s golfing year?

Hole No. 11 – White Dogwood Par 4 1933: 415 yards 2009: 505 yards

One of the more comprehensively altered holes at Augusta, the long par-4 eleventh debuted as a mid-length two-shotter played from a tee situated just behind the original tenth green (i.e. short and right of the hole’s present putting surface) to a green occupying essentially the same spot as at present. This made the hole a fairly pronounced dogleg right whose primary challenge lay in placing one’s drive in the center-right section of the fairway, for anything drifting too far left brought a corner of Rae’s creek – which lay several yards left of the putting surface – considerably more into play. Early drawings indicate the presence of a centerline mound within the driving zone, presumably to help “distribute” drives leftward or rightward, but this hazard was replaced by an invisible, St. Andrews-inspired bunker prior to the first playing of The Masters. The resulting test was quirky and apparently fun, leading MacKenzie to observe: “This should always be a most fascinating hole. I don’t know another quite like it.”

Unfortunately, “always” proved to be less than 20 years, for in 1950, the hole was substantially reconfigured, with a new tee constructed to the left of the tenth green, turning the eleventh into a nearly straight 445-yarder that began with a semi-blind drive to a cresting, wooded fairway. The turn in Rae’s creek was widened into a pond and brought flush to the green’s left apron, while the back-left section of putting surface was extended behind this new and intimidating hazard. Further, two rear bunkers were added to the green complex in 1953, though only one of the pair survives today.

The resulting hole created a fascinating strategic question for better players: was the preferred angle of approach from the far right side of the fairway, where the most direct line into the front of the green could be found? Or perhaps from the far left, where the pond might be turned into something of an easier-to-measure frontal hazard?

Sadly, this intricate and fascinating strategy was rendered moot in 2002 when, at the club’s request, Tom Fazio narrowed the fairway considerably by planting both trees and rough. While this method of so-called “Tiger Proofing” was also implemented on a number of other holes, its impact on number eleven was particularly noticeable. This, combined with a recent lengthening to an absurd 505 yards, has turned a truly captivating tournament hole into a brainless, one-dimensional exercise in compulsory golf.

Better Then or Now?

How about somewhere in between? Though the eleventh circa 1935 was an inventive sort of hole, it would unquestionably have required modification in the modern era, both in terms of length and bringing the greenside water hazard more prominently into play. Conversely, the present hole – though palpably difficult – stands virtually antithetical to the very concepts upon which Jones and MacKenzie based the entire Augusta project. Remove the rough and trees, however, and once again allow the players to actually do a bit of thinking, and we just might have something…

Hole No. 12 – Golden Bell Par 3 1933: 150 yards 2009: 155 yards

Arguably the most famous par 3 in golf (and surely the most consistently dramatic) the 155-yard 12th has undergone several significant changes over the decades, most of which seem largely forgotten today. To begin with, though a set of published drawings showed both this and the thirteenth greens as having been planned bunker-free (“It will be noted there is not a single bunker at either of these holes” – MacKenzie), the evidence is clear that the front bunker was indeed included during initial construction. The two rear bunkers were added sometime later, carved into the rear hillside above a shallow, poorly draining swale that originally backed the putting surface.

With this swale’s seemingly permanent dampness causing numerous embedded ball issues (including a famous 1958 ruling that helped Arnold Palmer to win his first Masters), a substantial project was undertaken in 1960 to elevate the entire green area some two feet. The net result makes for interesting viewing when comparing pre- and post-1960 photos: the rear bunkers, once carved into the back hillside at a level noticeably above the putting surface, are now drawn almost level.

Perhaps more significant are the changes that have overtaken the green itself, for today’s flattish, almost symmetrical putting surface belies a far more colorful past. Indeed, prior to a 1951 expansion, the right side was considerably smaller than the left, requiring some major skill (not to mention guts) if one elected to have a desperation go at the traditional final round pin. Additionally, as suggested in MacKenzie’s green sketch, this smaller right side was elevated significantly above the left – a substantial difference from the relatively flat surface in play today.

Better Then or Now?

Then – probably. Most would agree that the elevation of the green was certainly a positive, solving the dampness issues that provided the potential for endless rules controversies, and removing the “elevated” appearance of the back bunkers in the hillside. But the less-symmetrical, more-contoured putting surface was surely more interesting than that in play today, which inevitably made for even greater theater on those earlier Masters Sundays.

Hole No. 13 – Azalea Par 5 1933: 480 yards 2009: 510 yards

As dramatic a par 5 as has ever been built, Augusta’s legendary thirteenth has retained its general configuration fairly well – but a number of smaller, less-obvious changes have taken place. Like the twelfth, MacKenzie’s plan for the thirteenth green indicated a complete absence of sand, but again, things seem to have evolved quickly, as three flashy bunkers were carved into the back hillside either during construction or in preparation for the inaugural Masters. The putting surface itself has also been altered, being slightly re-contoured during the 1950’s, then entirely rebuilt by George Cobb in 1975. A resulting swale that bordered its left and rear flanks was ultimately judged too severe, and was subsequently softened in 1988, and even a cursory comparison of images of the fronting creek over the years makes clear the extent to which it has been widened, and otherwise cosmetically touched up.

The one really obvious change to the green complex came in 1955, when a fourth bunker was built immediately adjacent to the creek, replacing a narrow, front-left sliver of putting surface. This confined finger of green, squeezed tightly between the creek and the hillside, was a vintage piece of asymmetrical MacKenzie design, and would surely offer yet another dramatically tempting pin placement were it still in existence today.

Also evolving over the decades has been number thirteen’s length. The club originally listed it at 480 yards, but that number has been revised both upwards and downwards over the decades, ranging from a shortish 465 (its 1980’s Masters yardage) to as much as 485 during the 1970’s, when the tee was extended onto a bit of land purchased from the adjoining Augusta Country Club. More recently, as part of Tom Fazio’s new millennium makeover, even more neighboring land was purchased, allowing the hole to now measure a full 510 yards.

Better Then or Now?

Then – if we’re judging pound for pound. The only significant problem with today’s hole is that at 510 yards, the balance for Masters participants seems to have shifted a bit too far towards laying up, thereby diminishing some of the most dramatic moments in all of competitive golf. But the original version also had the front-left extension of the putting surface which, one senses, would offer particularly exciting possibilities to modern tournament players. Why not bring it back?

Hole No. 14 – Chinese Fir Par 4 1933: 425 yards 2009: 440 yards

The dramatically different 14th is famous today as a bunkerless hole. Clearly, MacKenzie didn’t always envisage it as such.

The par-4 fourteenth could stake a claim as Augusta’s least-altered hole, save for one significant change: the 1952 removal of a huge, wildly shaped MacKenzie bunker protecting the preferred right side of the fairway. True, this bunker – which was, by a considerable margin, the largest on the golf course – would not be relevant to today’s top players, but given its prominent place upon the landscape, the aesthetic difference is enormous. Also altered is the teeing ground, which was moved leftward and forward in 1972 (to create space relative to the thirteenth green), then extended back to its current 440 yards during Tom Fazio’s 2002 reworking.

Better preserved has been the green, a true roller coaster of a putting surface whose enormous bumps and undulations lead to all manner of creative approach shots each April. But even this Golden Age work of art is not altogether intact, for its back-left corner was extended a bit in 1987, its front edge has been brought noticeably forward, and multiple flanking mounds have been soften or removed over the decades. But watching the occasional smartly played Masters approach land thirty feet from the pin, turn 90 degrees, then ultimately trickle down to within inches of the cup, one cannot help but recognize that this remains, in many ways, the last true footprint of Dr. MacKenzie at Augusta.

Better Then or Now?

In real terms, it is little different – though a net gain of 15 yards in length surely isn’t enough to negate the effects of unchecked modern equipment. MacKenzie, however, had a purpose for his lost fairway bunker: tee shots which carried it were left with a clear view of the putting surface for their second, while balls played safely left stuck the golfer with a semi-blind approach over the now-deceased frontal mounding. The bunker would little affect today’s best in its original position, but what if, like fairway bunkers at the fifth and eighth,, it was restored somewhat further downrange?

Hole No. 15 – Firethorn Par 5 1933: 485 yards 2009: 530 yards

Always a short, straightaway par 5, the fifteenth has forever been reachable in two, initially because Bobby Jones believed that all par 5s potentially should be, and more recently because the presence of the eleventh fairway leaves no room to extend the tee back any further. Though, at a glance, things may not look too different today relative to the early years, the hole has seen its fair share of changes.

First, what began as a smallish creek meandering before the green was eventually widened, and enlarged into today’s famous pond, though accounts of just when this took place vary, ranging from 1947 through the early 1960’s. Also, a mound sitting just off the right edge of the putting surface was replaced by a bunker – at the apparent suggestion of Ben Hogan – in 1957. Additional mounds around the green have been added and removed, and a controversial series of mounds were added on the right side of the driving zone in 1969.

Of course, nothing has affected the fifteenth quite so much as the effect of trees along its fairway – and not just those installed around the new millennium. Once upon a time, the plain that encompasses parts of the second, third, seventh, fifteenth and seventeenth fairways was largely a wide open stretch, dotted only with the occasional pine tree. Two of those original pines formed the foundation of the large cluster of trees that now cuts into the left side of the fifteenth’s driving zone – so that particular copse is not entirely contrived – but the budding mini-forest which now occupies a stretch of former right-side fairway most certainly is.

And then there is a subtle, yet hugely important, agronomical difference: with the slope separating the front of the green from the pond now maintained with the firmness of a billiard table, the margin for error on approaches coming up fractionally short has been reduced to near nothing – a circumstance which affects heavily spun pitches more than longer irons from atop the hill, and thus might actually induce more players to go for the green in two.

Better Then or Now?

One certainly sympathizes with Masters officials who’ve grown weary of watching longer hitters reach the fifteenth green with short-iron seconds, so the hole’s recent lengthening to 530 yards certainly makes sense. The problem, once again, lies with the addition of rough and trees, both of which run directly against the philosophy of Bobby Jones, who specifically wanted players to have a go at this green in two. Jones wrote favorably of the fifteenth that “The tee shot may be hit almost anywhere without encountering trouble,” because he considered this a necessity in setting up the unique approach that has produced so many of championship golf’s most thrilling moments.

Hole No. 16 – Redbud Par 3 1933: 145 yards 2009: 170 yards

The famed par-3 sixteenth, site of so much Masters lore and the last of the layout’s true all-or-nothing tests, bears the unique distinction of being the only hole which was not a part of the original Jones and MacKenzie design. Indeed, their original sixteenth hole – now virtually forgotten – was listed at 145 yards and ran nearly due west, emanating from alternate tees on either side of the fifteenth green. Its putting surface sat in an area between the present hole’s pond and the edge of the sixth fairway, and was flanked closely on its right by the creek that once crossed the sixth, and not so closely on its left by a pair of bunkers. MacKenzie cited the seventh at England’s Stoke Poges Golf Club as its inspiration (a rather more obscure choice than earlier St. Andrews and North Berwick influences) and seemed generally to have liked the hole.

Unfortunately, club officials were less enamored with it. Clifford Roberts estimated that the original actually measured little more than 110 yards and, we are told, early Masters participants found it far too easy. Thus Robert Trent Jones was brought aboard in 1947 to construct the present, highly dramatic sixteenth, reportedly executing a concept laid out by Bobby Jones himself.

Better Then or Now?

For the purpose of The Masters, it is difficult to argue that the current hole – despite offering little more than two really effective pin placements on a larger-than-average green – isn’t far better suited to the rigors and excitement of modern tournament play. For the membership, however, the old sixteenth might have held more charm (and obviously more MacKenzie flavor), particularly as there was room to lengthen at least its left-side tee considerably. But on balance, it would be hard to suggest that the modern hole doesn’t better suit the club’s all-around purposes, the staleness of Trent Jones’s aesthetics (at least relative to Dr. MacKenzie) notwithstanding.

Hole No. 17 – Nandina Par 4 1933: 400 yards 2009: 440 yards

The par-4 seventeenth was originally built as the last of Augusta’s bunkerless holes, its shallow, swale-fronted putting surface leading Dr. MacKenzie to opine that “It will be necessary to attack the green from the right and it will be essential to play a run-up shot if par figures are desired.” Somewhere early on, however, this strategy was rejected by the club when it chose to add three bunkers, the two which presently front the putting surface and a third – long since removed – well short and left, the net result being that no modern run-up shot is played intentionally. For all intents and purposes, it is thus an entirely different hole than that built by Jones and MacKenzie.

Of course, the seventeenth’s most famous feature lies considerably closer to the tee in the form of the Eisenhower tree, a now-massive loblolly pine sitting some 210 yards off the tips and occupying the left third of the fairway. Named for President Dwight Eisenhower, a prominent club member whose tee shots it regularly devoured, this 70-foot-high landmark was little more than a sapling when Jones and MacKenzie elected to leave it standing during construction. Yet despite its great stature, it remains far more menacing to members than to the professionals, who can generally carry it with ease, even from the new-millennium, 440-yard tee. The trees and rough which have substantially narrowed the driving zone since 1998, however, are far less easy for Masters participants to ignore.

Better Then or Now?

This oppressive rough and tree presence has essentially turned the seventeenth into a lighter version of number seven – another narrow, thought-free, U.S. Open special. But even more disappointing is the presence of the fronting greenside bunkers, for it would be especially interesting to watch today’s professionals attempt to approach the original, hazard-free putting surface, especially under modern, ultra-firm-and-fast agronomical conditions. Save perhaps for Ike’s tree, this has largely become just another longish, uninspiring par 4 – and a far less interesting hole than it was in 1933.

Hole No. 18 – Holly Par 4 1933: 420 yards 2009: 465 yards

The long 18th – which, we recall, was originally planned as the ninth – was intended from the start to be a demanding par 4, both in its tee shot (played over a small valley, and through a narrow chute of trees) and its approach (long and uphill, to a tightly bunkered, two-tiered green). Of primary importance to Dr. MacKenzie was the shape and bunkering of the putting surface, for its angling against/behind the deep front-left bunker was intended to favor a drive played to the far right side of the fairway – which, in turn, mandated flirting with the forest of pine trees that has long filled the dogleg corner. Both putting surface and greenside bunkering have been modestly re-shaped over the decades (including some initial 1938 work by Perry Maxwell) but as a whole, the green complex is at least conceptually consistent with the Jones and MacKenzie original. What has changed, however, is the removal (during the late 1940’s) of a largely decorative crossbunker that filled the fairway some 60 yards shy of the green – another aesthetically imposing hazard that would not be in play for the modern golfer.

In 2002, Tom Fazio built a new tee situated so far back as to nearly impede play on the neighboring 15th hole, while also planting several trees on the outside of the dogleg to minimize the option of deliberately busting a big drive into the relative safety of the club’s practice fairway. But an even bigger change to the tee shot came in 1966 when, after reportedly witnessing a young Jack Nicklaus’s remarkable power firsthand, Clifford Roberts ordered the addition of the two deep fairway bunkers that guard the outside of the dogleg. Of course, they’re situated nowhere near where the ideal right-side tee shot will finish, but they have certainly helped to make the eighteenth – particularly at 465 yards – one of the tougher finishers around.

Better Then or Now?

Since a hole built at 420 uphill yards in 1933 was clearly never intended to be easy, today’s long and strong version of the eighteenth may not play so very much harder than what Jones and MacKenzie had in mind. But in this case, such relative consistency may be unfortunate, because while 72nd-green birdies to win The Masters have never been common, the difficulty of today’s hole minimizes such prospects tremendously. It thus appears to be precisely the sort of closer that the club’s present architectural vision calls for – which, since the U.S. Open won’t be coming there any time soon, is really rather a shame.

How then, does the Augusta National in play today shape up overall against the Jones and MacKenzie layout of yesteryear?

In assessing this, we must first acknowledge one very significant (and often overlooked) factor: the really substantive alterations that have taken place – wholesale changes at the seventh, ninth, tenth, eleventh, sixteenth and seventeenth – all occurred within the first two decades of the club’s history, and with the blessing (stated or implicit) of a still-very-much-alive Bobby Jones.

Recognizing this, we are then faced with the question that forever dogs any then-versus-now or restorative course discussion: which older version, exactly, are we comparing the present layout to? The much shorter, sparsely bunkered, 1933 layout which would at once be overwhelmed by modern power, yet also remain enormously challenging around a number of its more steeply contoured putting surfaces? An early 1950’s version, which incorporated the above-referenced major changes but not, for example, the decimation of the eighth green?

Speaking in general terms, the one indisputable difference between any early version and the present surely lies in the narrowing of fairways via the addition of rough and trees, moves which have sacrificed a significant degree of Augusta’s strategic challenge – and very nearly all that initially made the layout such a unique and groundbreaking advance in the field of golf course design. But at the same time, can there be even the faintest doubt that the present course, despite its myriad imperfections, is infinitely better suited to hosting a modern Major championship than even a realistically lengthened version of the 1933 track?

Thus the most logical question becomes not whether Augusta circa 1933 would be a “better” golf course than that in play today – because with so many changes to both the purpose of the layout and the game in general, they have essentially become non-analogous beings. Instead, it might be constructive to ask where, and in what specific ways, today’s club bosses might choose to dial back the clock on various changes, so as to find the optimum balance between what can be salvaged of Jones and MacKenzie’s original work and the demands of contemporary championship play.

In any such discussion, the one blanket change that would seem inarguable for a club claiming to so revere its past is the removal of the rough. MacKenzie in particular decried its use as a so-called hazard (observing that it created “a stilted and cramped style, destroying all freedom of play”) and its presence today represents little more than a panicky, simple-minded attempt at raising scores. Assuming its strategy-killing presence to be removed from the landscape, then, additional alterations/restorations might include the following:

Hole No.1 – Remove the row of trees most recently added off the left side of the fairway, a relatively minor change given that approaches played from the left side are already challenged substantially by the front-left bunker. Would the hole play slightly easier? Perhaps. But with a robust 4.24 average in 2008 (fourth hardest overall), such would be a small price to pay in setting a tone for this historically minded quest.

Hole No.2 – Rebuild the deceased left-side fairway bunker, far enough downrange (and positioned invasively enough into the dogleg corner) to make airmailing it something less than a given. Then remove Gene Sarazen’s right-side replacement bunker; if players wish to bail out right, add significant length to the hole and risk finding the right-side woods in the process, let them. It is also tempting to consider unearthing the long-buried creek that Dr. MacKenzie originally planned to have crossing the second-shot landing area +/- 70 yards shy of the putting surface – but from a traditionalist perspective, that might well represent pushing the envelope a bit too bar.

Hole No.3 – Replace Jack Nicklaus’s four fairway bunkers with a restored version of the original single hazard, slightly repositioned if necessary. For aesthetic/traditionalist reasons, mostly.

Hole No.7 – Though it’s tempting to suggest restoring the original bunkerless, Valley-of-Sin-fronted putting surface, the reality is that for most living Masters fans, the character incumbent to the seventh lies in its revised, heavily bunkered green complex. So in order to return some greater playing interest, and minimize the now-annual complaints from Masters participants, how about either shortening the back tee to a distance more in line with the actual affects of modern equipment (perhaps in the 405-420 yard range) or remove several of the most recently added trees to allow players some reasonable room to maneuver the driver? True, Bobby Jones did speak in positive terms of a driving area made increasingly narrow by the natural growth of trees during the 1950’s, but it’s difficult indeed to imagine he’d similarly endorse the strategy-less, U.S. Open-like hole presently in play.

Hole No.9 – Restore Dr. MacKenzie’s original single-bunker, boomerang green, a remarkably striking feature offering all manner of exciting pin placements – and whose right-side false front could still, with perhaps a bit of minor massaging, provide the same roll-down- the-hill dangers incumbent to present first-tier pins.

Hole No.11 – Remove at least 80% of the trees planted down the right side in 2002. This, combined with the eradication of rough, would re-open the far-left and far-right avenues of play, once again allowing the eleventh to pose one of the game’s wonderful strategic questions instead of simply being a backbreakingly brutal test.

Hole No.12 – Could it hurt to once again have the right half of the green just slightly smaller than the left, and perhaps just a little bit elevated?

Hole No.13 – A modest shortening (say 10-15 yards) might shift the balance back towards going for the green in two, making one of golf’s most uniquely dramatic shots a more regular occurrence – and leading to more than the eight eagles recorded for the entire 2008 event. Further, how about reducing the size of the first greenside bunker and re-establishing the lost section of putting surface that extended forward along the creek bank, creating a really dramatic pin placement whose slightly shorter carry might tempt even more players to have a go?

Hole No.14 – Rebuild both Dr. MacKenzie’s massive right-side fairway bunker further downrange, and some of the front-left green mounding removed in the modern era. Such changes would succeed in re-establishing both the clear advantage gained from placing one’s tee shot down the right side and the hazard that can make accessing this area of fairway a dicey but exciting proposition.

Hole No.15 – Remove the right-side trees, and thin the left-side copse down to its original two pines. This, combined with the renewed absence of rough, would restore the type of hole that Bobby Jones so extolled, surely resulting in more than the three (!) eagles recorded in 2008, and helping to restore the sort of Sunday afternoon drama so plainly absent in recent Masters.

Hole No.17 – Wouldn’t it be interesting to watch the world’s best attempt an utterly unfamiliar run-up shot – to a front pin perched just above the swale, in ultra firm-and-fast conditions – on Sunday afternoon with the Green Jacket on the line? Remove the bunkers from what is presently a patently mundane hole.

Hole No.18 – The eighteenth was built to be a demanding test, and 72nd-hole birdies to win The Masters were nearly unheard of before its recent lengthening anyway – but wouldn’t Sunday afternoon be that much more fun with this hole playing, say, 20 yards shorter, allowing players a chance to hit at least a semi-attacking approach?

And one final point: While MacKenzie’s bunkering at Augusta was fairly tame relative to his 1930’s aesthetic norm, the original hazards were still considerably more adventurous than the bland, cookie cutter-like ovals that inhabit the course today. Thus while Augusta may not be able – or wish – to restore most holes to their original configurations, and its altered putting surfaces must retain their modern contouring as a nod to contemporary green speeds, wouldn’t it be nice if the club re-established at least some of its original flavor by restoring the bunkers to MacKenzie’s original, unique shaping?

Beyond the architectural particulars inherent to individual holes, there are several broader conclusions which might reasonably be drawn when comparing Augusta National then and now. The first is that Jones and MacKenzie’s original design really was revolutionary, demonstrating brilliantly that a golf course didn’t require narrow fairways, 100 bunkers and 10 water holes to challenge the world’s best – and thus could be genuinely playable for the average golfer in the process. To the extent that this has largely been sacrificed with an eye towards The Masters might, depending upon one’s priorities, be forgivable. That such changes have managed to result in far less exciting Masters finishes, however, isn’t.

Also, though not a course design issue in the strictest sense, one would be remiss not to note the unfortunate impact that Augusta’s conditioning has had on the game of golf worldwide. This, of course, does not reflect any ill intent on the club’s part; they simply have boatloads of Masters money to dispose of, and, understandably, choose to put a great deal of it into the golf course. But there can be little doubt that their surrealistic maintenance standard has made many an American greenkeeper miserable, as gullible green committees have demanded comparably spotless results (generally on one-fifth the budget), often getting softer, duller and considerably less eco-friendly playing conditions in the process.

But in the end, perhaps the biggest difference between Augusta then and now is simply the role of Bobby Jones. For it was Jones’s vision that brought aboard Dr. MacKenzie, and led to the creation of so stunningly unique a golf course – a layout that was the living embodiment of all he believed comprised great design. Jones did, in fact, sign off on numerous course changes made during his lifetime, but when one considers the reduced modern playing strategies of many holes, par 5s which no longer tempt so many aggressive second shots and, above all, the recent addition of rough and trees, it becomes difficult to accept the notion that Jones’s wishes for his golf course are still, in any meaningful way, being adhered to.

To stray from these wishes, for whatever reason, is absolutely the club’s prerogative. But such architectural adventurism would undoubtedly seem less offensive if it weren’t forever masked in claims of reverence to Jones and his vision – a vision which is blurry, at best, on the golf course today.

THE END