A Round of Golf Courses: Bernard Darwin

as compiled by Tom MacWood

August, 2007

Bernard Darwin at Rye Golf Club.

‘There are few people so modest that they have not some little accomplishment which they like now and again to show off. Mine is a particularly tiresome one, tiresome, that is, to other people, though full of intense pleasure to the owner. It consists of reeling off certain lists of names of very doubtful interest to anybody but myself. They are a miscellaneous lot, and among them are the five members of the Cabal, the Knights Challengers in the two tournaments of Ivanhoe (any schoolboy can do one), the first four wranglers in Frank Fairlegh’s year, and the Cambridge eleven in 1878. The Seven Bishops I have, alas! forgotten, and I always come to grief over Mrs. Nickleby’s lovers. As regards my golf, my one little trick is, I am convinced, rare, but may strike the modern golfer as singularly futile. It is the list of the eight courses in England, in their correct order, over which Mr. Horace Hutchinson halved his great match against the mythical opponent, James Macpherson. Hoylake, Westward Ho!, Bembridge, Wimbeldon, Blackheath, Felixstowe, Yarmouth, Alnmouth.’

Most golfers enjoy lists, not only making their own but reading what respected figures like Horace Hutchinson mark down as the best, and apparently Bernard Darwin was no different. The preceding excerpt was how Darwin introduced his contemporary list of the ‘main golfing greens of England’, an article inspired by Hutchinson’s ‘Round the English Golf Links’ from 1898. The subject of list making and identifying the best courses came to me while re-reading A Round of Golf Courses written by Patric Dickinson. This wonderful book profiles Dickinson’s 18 ‘best’ golf courses around the British Isles: Aberdovey, Carnoustie, Ganton, Gleneagles, Harlech, Hoylake, Hunstanton, Little Aston, Moortown, Muirfield, North Berwick, Portrush, Rye, St. Andrews, Sunningdale, Walton Heath, Westward Ho!, and Worlington. One of the highlights of this little gem is the brief forward written by Darwin praising Dickinson’s descriptive abilities while gently admonishing the exclusion of Prestwick. That admonishment inspired a question: What 18 would Darwin have selected?

Unfortunately BD never produced a Dickinsonesque 18, or if he did I have yet to find it. However he did recreate Hutchinson’s 8-more than once I discovered. In fact identifying the best courses was something of a personal obsession with Darwin. The annual Golfer’s Handbook contained a ‘who’s who’ section that profiled the distinguished golfers of the day, including a listing of their favorite courses. Cataloging and analyzing their choices was a reoccurring theme for Darwin, although ironically BD’s own profile listed no favorites, his alibi, “Perhaps I was too modest or too cautious; perhaps my list grew too long; perhaps I began to think myself a bore with my Aberdovey and Worlington. I cannot say what were my motives, but at any rate the reader will not be troubled with any defense of my choice, which is all the better for him.”

So without a definitive list I set out to compose one for him. Before I begin let me acknowledge it is highly presumptuous to claim one knows what a past figure would do or say-especially someone of Darwin’s stature. With that being admitted I hope I can be forgiven on the grounds that any exercise that celebrates Darwin and great golf courses is a good exercise, and based on his track record I don’t think it too far fetched to believe BD would have relished this game.

As I said, my challenge was to identify Darwin’s best or favourite 18 (‘best’ vs. ‘favourite’ will be addressed later). One advantage we did have was the wealth of material Bernardo left us; the man wrote more articles than all his contemporaries combined. I cannot claim to have read everything he ever wrote, but I can tell you I have searched far and wide for everything he wrote relating to golf courses – hundreds of articles, if not more, from The Times, Country Life, other publications, and of course his numerous books. After compiling and analyzing these articles I came up with a list of about thirty favorites, which I eventually whittled down to 18, the last two or three being the most difficult. In the end I feel content this round of golf courses is representative of Darwin with one or two possible exceptions, and those can be attributed to artistic license on my part. So, without further ado…

Outward Nine

Sandwich

“There was once a little girl who, on being told she was going to be given a dog, said: ‘May I get under the table to think about it?’ She felt the need of secrecy and solitude and of a more concentrated atmosphere in order to gloat over so heavenly a prospect. I feel a little like her at this moment. I shall not take such acrobatic measures, but I feel a distinct desire to gloat. In my case the prospect is that of seeing Sandwich again-in a good hour be it spoken-after an interval of nine years. In 1939 the University match was played on the links of the Royal St. George’s Golf Club, and I have not been there since. The confession seems a shameful one, but it is true. Now towards the end of March, to be precise on the 24th and 25th, the match is to be played there once again, and, if that were not stunning enough, I have been asked to stay in a friendly house near by, where I have spent happy days in the past. So if I metaphorically get under the table to think about it, I hope I may be forgiven.

To those of my own University generation it is always a delight when this match is played at St. George’s, because in our time it was regularly played there, so that we came to think of Sandwich as, so to speak, the Lord’s of the match, and have always felt it something of a profanation to play it anywhere else. That is a personally sentimental feeling for our old battlefield, confined to a few now decrepit warriors; but, leaving it on one side, Sandwich is a spot that inspires a deep affection in all who know it. There are, of course, many golfing places of which its admirers say that there is a nothing like it, but there is, I think, no single one of which it can be said with more heartfelt conviction. Literally it cannot be quite true for close by is the noble course at Deal, which is in many ways very like it, and so was Prince’s, now alas! no more, which lay cheek and jowl with St. George’s. Nevertheless, everything at St. George’s from the very trees round the clubhouse has for its devotees an extraordinarily characteristic flavour. Other courses have mighty sand-hills, but there is a secrecy about the little winding paths among the Sandwich hills which give it, in my eyes at least, an unique fascination of mystery. We may be among a multitude there and yet in solitude.

St. George’s has long since settled down to a high and acknowledged place among great links, but in its earlier days it fluctuated considerably in point of reputation. It was new when I was very new indeed, and in those days golfers whispered of it in terms of positive awe. There never has been, so I used to gather as a boy, a course of such tremendous hills, such vast unthinkable carries. People in England, at any rate, were perhaps more simple-minded, and were swept off their feet by the thought of anything so colossal. They spoke of the towering height of the Maiden and the huge, sandy waste of the Sahara with bated breath. Even the Suez Canal sounded as if it were something appalling and tremendous which no man could hope to cross.

Then after a while, there rose those who looked upon the course with clearer and more critical eyes and saw its defects as well as its splendours. Freddie Tait’s terse comment, ‘A good two-shot course,’ was repeated from one to another. It seemed to some almost blasphemous, and yet there might be something in it. There were great carries from the tee and there were large and lovely putting greens, but driving and putting were not everything, and there were perhaps weaknesses in between.

There were undeniably many blind shots, played over high mountains and on to greens in hollows, wherein the ball might travel on the wings of chance. So for a while the stock of Sandwich fell, fell probably lower than it ever deserved. Then with a variety of changes in the course it rose again. The old ninth, the Corsets, with its two blind steeple-chasing shots over two boarded bunkers-they admittedly produced a pleasing sensation of terror-disappeared and there came in its place the infinitely superior hole with its narrow, visible green as we know it today. No one who ever played it can resist a certain unjustifiable regret for the old seventeenth in its deep cavernous hollow, now over-grown and neglected, without a little sentimental feeling in his inside. But the present hole on the plateau is incomparably better in every way, and the same may be said of the present tenth, one of the best and most exacting of all plateau holes, which superseded another blind hole in a deep pit. The new fifth, in itself a very fine hole, did take away the old, rudimentary but still impressive glories of the Maiden; but of all the changes that was the only one that could be criticized. From that process of reformation Sandwich emerged radiant and transfigured, still a fine course for the driver to open his shoulders on, but giving ample scope for all the other strokes in the game.

Apart from these individual changes one general change has come over Sandwich since I first knew it, or at least so I think. That is in the balance of the course, if I may so describe it. Once upon a time the carries and the shots in general were on a grander scale going out, the chances of utter destruction the more terrifying; but there were three threes to be possibly obtained, at the Sahara, the Maiden and Hades (the 3rd, 6th and 8th), and so if the grosser sins were avoided at the other holes, a fairly low score was possible. On the other hand, the home-coming nine, though less picturesque and alarming in aspect, regularly cost more strokes. At the 13th, 14th and 15th, for instance, the ordinary mortal, even though he could hit reasonably far, could not hope to do better than three fives. With a gutty ball indeed he was very thankful to get them; the Suez Canal with any adverse wind was much more likely to cost him six. There was only one three to be had, as indeed there still is, at the 16th, and some other fives were sure to creep in. Such a score as 37 out and 42 home did not mean any falling off on the way back. Rather it represented something a like a fair balance between the two halves. To-day the foundation of a really low score is still laid in the first nine, but the long hitters no longer take fives on the way back as they once did; no matter where the tees are they seem to be able to crash their way home in two shots. At any rate, the homeward scores they do always astound me, who cannot altogether rid myself of my old-fashioned standards.

When thinking about Sandwich I looked at an early book called British Golf Links, which was edited by Horace Hutchinson and published in 1897. There I found a little piece of knowledge new to me. It seems that the first man to discover the potentialities of the place was a schoolmaster, some time about 1867. He was a patriotic Scotsman and used to take out his pupils into that waste of sand-hills and try to make them appreciate the beauties of his native game. They were apparently obdurate, but the master continued to believe in his dream of golf which some twenty years later came gloriously true. Let us hope that his ghost gratefully re-visits the scene of his once fruitless labours amid those stupid little English boys.

Meanwhile I gloat at the thought of re-visiting, not quite yet a ghost, the scenes of some Cambridge victories. Candidly I do not expect to see one this time, what of that? I hope to take that dear little hidden path from the third green to the Maiden and there perch myself on its summit and look across Pegwell Bay. And so, as the announcers say, ‘Over to Sandwich.'”

Three Great American Courses

Darwin made two trips to the United States. The first came in 1913 when Vardon and Ray made their historic tour. Lord Northcliffe, the owner of The Times, sponsored their trip and Darwin was dispatched to cover it. During the tour he recorded his impressions of Garden City, the National Golf Links, Myopia, Brookline and a number of courses around Chicago. His second visit came in 1922 when he was assigned to report on the Walker Cup at the National Golf Links. The reporter became a competitor when the British Captain fell ill, and Darwin was forced to take his place. Although the British side fell, Darwin did win his singles match against William Fownes despite an inauspicious start: “While I was out playing some practice shots, a ball hit by another practicer, hidden from sight, hit me on the breast-bone. I thought for a moment that here was a state of things if the only available substitute was killed. Then I realized that I was none the worse, and that the ball had been spent and lifeless.” On this trip BD visited Pine Valley, Piping Rock, The Links, Westchester and the now extinct Lido.

Lido

“The Lido is the work of Mr. CB Macdonald, the creator of the National, and besides having a genius for golfing architecture, he must have the imagination of a poet and a seer. Otherwise he never could have envisaged the possibility of making the course. As we drive along an abominably bumpy road towards Long Beach, which is a superior sort of Coney Island, we see the material out of which the Lido was made. It is a perfectly flat stretch of green swamp-nothing more nor less. Yet the golf course is a seaside course of pure sand, full of gentle undulations and imposing hills bristling with bents; it is, in short, just like one of our own seaside courses at home, save that it is more difficult and, in my judgment, better than any of them. How was this miracle accomplished? Briefly, vast engines sucked up the sand of the sea and spread it over the swamp in all these various undulations. I must omit the different processes of laying down soil and humus, the sowing and turfing, because they would take too long to tell and I do not know them accurately enough; but the main miracle is the simple but stupendous fact of sandy hills being artistically dumped all over the flat muddy marsh.

The course is very long and very difficult, but it is full of interest and never tricky or fantastic. We never feel there, as we occasionally do nowadays, that the creator of the course is sitting metaphorically with his fingers to his nose behind one of his bunkers and laughing because he has scored off us. Undoubtedly the punishment is severe because the rough, which is both sandy and benty, hardly ever relents. Once in there, only a niblick as a rule will get us out again. On the other hand, the bunkers near the green give us a fair play. We do not get in them unless we deserve to, and we can get out if we can play the right shot. There are one or two holes, as is usual with Mr. Macdonald’s creations, which are modeled on-not slavishly copied from-famous holes at home. There is an Alps from Prestwick and Redan from North Berwick. I think, however, the two very best holes are the fourth and the eighteenth. The fourth is the most majestic two-shot hole I have ever seen, with a carry over a wilderness of bents from the tee and then home another great shot over the big bunkers on to a great plateau green. The eighteenth should have a particular interest to Country Life because it descends from it. Just before the war Mr. Macdonald offered to give me for Country Life three prizes for the best design for a two-shot hole. Mr. Horace Hutchinson, Mr. Herbert Fowler and I were the judges, and all the designs were sent in such a way that we did not know who were their authors. We unanimously gave the first prize to a design that turned out to be Dr. Mackenzie’s, and there at the Lido today this hole is faithfully reproduced with its three alternate routes for the tee shot and, for the big hitter, a glorious lash home for the second.”

Pine Valley

“If the Lido course reminded us in one way of home so did Pine Valley in another. In Surrey at a range of twenty to thirty miles of London, we have a number of courses in which the two chief ingredients are sand and pine trees. Therefore the green glades of turf winding here and there amongst the firs are distinctly familiar to us though no one of our courses of this type is conceived on so big a scale as is Pine Valley. Here, too, there is more than architecture.

The late George Crump must have had more than a touch of prophetic imagination as well. His was, I believe, the original conception and his design was modified by the advice of Mr. Colt and his partner Mr. Alison. The result is truly remarkable, but in order thoroughly to appreciate it we must know what was in Mr. Crump’s mind when he first thought of the course. This was, as we were told on our visit, that somewhere there ought to be one course where, as far as humanly possible, the best man on the day should win because every bad or indifferent shot should meet with its reward. That is a high but a very severe ideal. It relegates mere pleasure in playing to a minor position and personally I think there are just one or two holes at Pine Valley which are too hard work to be pleasant.

The tee shots are difficult but they are very interesting and not unfairly difficult. The rough is cruel, indeed, and you may find yourself almost unplayable in the woodlands, but there is adequate room and the fault is yours. What we Britons were disposed to criticize was the almost fantastic severity of the traps guarding some of the greens. They are so close to the greens, so omnipresent that is dreadfully easy to get out of one into another and then back again to the end of the chapter. This almost amounts to eternal punishment and eternal punishment had better be left for the day of judgment.

The hole I have particularly in mind is the eighth where the green is very, very small and rather fast and sloping into the bargain. There really seems here no limit to the player’s liabilities and there is a touch of trickiness and freakishness which is unworthy of so magnificent a courses. In one or two other instances the policy of undulating the green is to my mind carried a little far, but the eighth is the one real sinner. I admit that I took something more than an eight to it myself, but I hope that this has not warped my judgment. I should like to see the green bigger and at least a measure of Christian charity shown at the back of it in place of yet another trap.

Having got this off my chest I could write pages of admiration on many of the holes-the second, for instance, with its green perched so defiantly above a big sandy bluff; the eighteenth a really superb finish with a long second to be hit right home over a water jump and a big bunker; the thirteenth and sixth, two beautiful ‘dog leg’ holes, both scrupulously fair.

Again what a memorable short hole is the fifth-one full spoon shot over a tremendous chasm stretching from tee to green, a wilderness of fir trees on the right, big bunkers on the left. To land the ball on that green-and there is no reason in the world why you should not do it if you are not frightened-provides a moment worth living for. It is a wonderful course, yet my final belief, right or wrong, is that the pleasure of playing Pine Valley would be greater even than it is, if a few more concessions were made to human weakness. A game is not a competitive examination.”

National Golf Links of America

“I shall never forget the moment of my first arriving at the National. It was well timed, for the sun was just setting; we drove along a lonely sandy road amid huckleberry bushes. Everything was seen in a half-light, fading and fantastic, and on the horizon was a broad strip of flame, while between it and the waters of Peconic Bay there ran a narrow strip of jet black that marked the curve beyond the Bay. Here, after stifling New York, was peace and coolness and seaside golf, and indeed, further experience has convinced me that, taking all things into consideration-the golf, the company, the view, and the cooking-there is in the world no more delightful place in which to play than the National Golf Links of America.”

“I went to stay with my very kind friend Mr. CB Macdonald, at his house near the National, close to Southampton on Long Island. Mr. Macdonald was the ‘onlie begetter’ of this great course, and is, so far as I know, the only golfer whose statue adorns the Club which he created. Not only did he create the National Golf Links, but probably more than any other one man he created American golf. Never was there a more forceful and dominating person, nor one more brimful of energy. Nothing can stop him. He will play golf all day in all weathers, sit up a considerable part of the night and catch an inhumanly early train the next mourning, as fresh as a lark. Moreover he is apt to feel a pity akin to scorn for those who cannot do likewise. An admirable critic of golf, he is also a stern one. I remember watching, in his company, two people playing off a nineteenth hole at the National, and that hole with its green cocked on top of the hill, with many surrounding bunkers, is never at the best of times an easy one. One of the players made a rather weak second. ‘That,’ said Mr. Macdonald, ‘was a chump shot.’ I ventured to say that it was a very difficult shot and the circumstances were exacting. ‘It was a chump shot,’ he repeated with terrifying abruptness. ‘The man’s a chump!’ and there was no more to be said about it. I have lived in perpetual fear of his thinking me a chump, but, if he does, he has concealed it under a mask of uniform friendliness.

Fictions die hard, and if ever one mentions the National to a British golfer his remark is almost inevitable, ‘Isn’t that the course where they made eighteen exact copies of the eighteen best holes over here?’ In fact, I fancy that many people visualize the course as consisting entirely of plasticene models on a gigantic scale. How many are there of such copies in fact? Well, the second bears some trace of the Sahara at Sandwich, the third is more or less like the Alps at Sandwich, the fourth is the Redan at North Berwick (American courses are spotted with Redans), the seventh is the seventeenth at St. Andrews, and the fourteenth is the eleventh at St. Andrews, with the added feature of a strip of water in front of the tee. That is five in all, and I think the general opinion is that some of the holes, which owe nothing to any model, are better than any of the copies. In one sense indeed the copies are almost failures. They are excellent holes in themselves and, as far as measurements are concerned, they are triumphs of imitative art, but they are not really like the originals. In fact, unless you have the same kind of turf and the same kind of wind, as are to be found at St. Andrews, you cannot copy a St. Andrews hole. You can pitch the ball right up to these holes on the softer turf at the National in a way that you would never dare at St. Andrews, even now that the classic course has become, by comparison with its ancient state, an inland one. One advantage the seventh at the Nationals has over its Scottish original is that in place of the black sheds of the stations-master’s garden there is a splendid wilderness of sand, and so no out of bounds; nor of course is there a road and wall behind the green, but only a bunker. Still the elder hole remains, I think, the better. The National is, however, a grand course with one signal merit, reflecting particular credit on its architect. It is essentially a long driver’s course in that long driving will gain its full advantage, and yet it is not a laboriously long course, being in point of actual yards decidedly shorter than many modern ones. Exactly how this effect is produced I do not know, but doubtless ‘the immense and brooding spirit’ of Mr. Macdonald did not ponder over it so long for nothing.”

Darwin’s final analysis: “My own opinion is that Pine Valley is the hardest; that the Lido, judged as a battlefield for giants is the best, not only in America, but in the world; and that I would rather play on the National than on either. Frankly, I am not good enough golfer for Pine Valley or the Lido. For that matter, I suppose I am not good enough for the National, but I can pretend that I am and can enjoy that delightful game of pretending.”

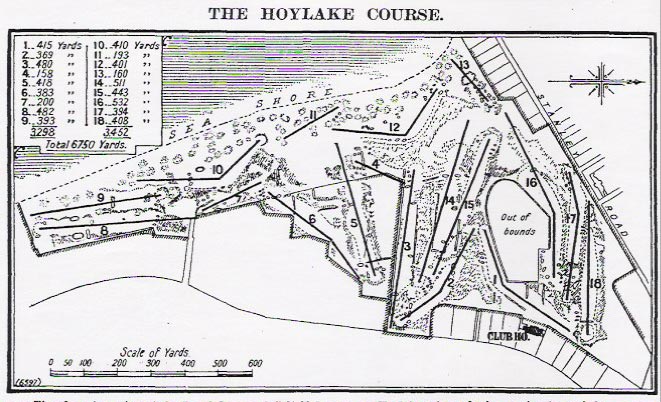

Hoylake

“Now we must hurry to England, and first of all to Hoylake in Chesire. Liverpool is a wonderful golfing centre, and Lancashire has wonderful golfing country, a country of sandhills and long, narrow valleys running between them. Formby, Birkdale, and Blundell Sands all possess this sort of golf, and very good and charming it its-but give me Hoylake. It looks flat, open dull, almost ugly, with its rectangular turf walls and the houses stretching out farther and farther along its edges; but what a golf course! Its greatness inevitably grows upon us the better we know it, and so come to understand its subtleties. There is one hole there beyond all others which illustrates this quality, and that is the seventh, always know as the Dowie. I have heard a very famous golfer, who ought to have known better, call it ‘the kind of hole you might find on Clapham Common.’ He ought to have known better as regards the merits of the hole, but it is a good description of its outward appearance. Here is a little three-cornered green tucked under a turf wall, with an out-of-bounds cabbage field on the other side. In front of the green is a rather scanty, straggling patch of rushes, and round the edge of the green runs the shallowest, most insignificant grassy dip; and that, except for some new bunkers a little way to the right, is all. Yet this is a magnificent one-shot hole, demanding the highest golfing qualities, whether of heart or of head or of technical skill. The same may be said of the wonderful first hole which at first sight may seem to consist only in tacking round two sides of a field with nothing in the way. In some respects Hoylake is like St. Andrews. It is essentially not the heroic golf of big mountains and spectacular carries, though it is a little more so than it used to be since the alterations [Harry Colt’s] have brought some of the sandhills into play. The topped shot can often go unscathed as far as direct punishment is concerned, and though there are some very narrow holes, there are others where there is a great breadth of fairway and no particular rough; but, as at St. Andrews, the man who makes a weak or crooked shot is going to pay for it by being left with a problem that is too hard for him unless he be very skilful indeed. Hoylake differs from St. Andrews in this, that there is much more compulsory pitching to be done; one or two of the old cross-bunkers have gone, but there are still a good many left, and the Hoylake-bred golfer has always been a good pitcher. It is also different in that it has been more elastic: there has been more room for the putting the tees farther and farther back, and no mortal man has ever said that Hoylake was too short. Indeed, the five last holes-the Field, the Lake, the Dun, the Royal, the Stand-make up the most strenuous and punishing finish in all the world of golf.”

BD’s thoughts on Colt’s alterations: “Not a rood of that sacred turf belongs to me: I have merely been a guest there more times than I dare reckon, and have no more right to criticize the bunkers than the potted shrimps. Yet in the recess of my mind I am inclined to adopt a proprietary air about the place.

Nobody, I imagine, will deny to Mr. Harry Colt unstinted praise for his eleventh and seventeenth holes, the new Alps and the new Royal. These are changes that count two on the division, for the old holes were poor and the new ones are admirable. The Alps consisted of an entirely blind one-shot hole and had little but its romantic name to recommend it. In its place is another one-shotter from an exhilarating tee to a narrowing green closely beset on one side by the shore and having perfect visibility. But this is a comparatively small improvement compared with that at the Royal. Today with its narrow green between devil of the road on one side and the deep sea of a horrid bunker on the other it is as fine and frightening a seventeenth as anyone can desire, and I imagine that many a reasonably stout heart with a good medal score will be tempted to play it by installments. It has already been the scene of one classic shot, Walter Hagen’s second when he wanted two fours for the Championship. It is worthy to be compared with another seventeenth in which the road plays its part.

The other three changes, namely the new greens at the Far or eighth hole, and the twelfth or Hilbre and the wholly new thirteenth, which has inherited the old name of the Rushes, are more open to criticism; not on the ground of any lack ingenuity on the architect’s part, but because, fine holes though they are, they are comparatively like many other fine holes to be found elsewhere, whereas those they have superceded were unique; they were essentially Hoylake. This conservativism can be pushed too far; I am ready to give up the old Hilbre, despite the fascination of that open simple approach made frightening by the pond behind the green; but I must shed a tear over the old Far green with its engaging run-in from the right. I cannot quite weep over the old Rushes, but I always remember that John Ball, to be sure an immovable Tory, said about it; that at the old hole the player had to for himself the work of getting the ball into the air and stopping it on the green, whereas at the new one the high tee did it for him.

I do not criticize the disappearance of the old cross-bunker at the Dun because that had been made inevitable by the modern ball and modern driving. It was sad to see it go if only because the soberest might fall into it after dinner-I have seen them do it-in finding their way home across the darkling links; but it had to go and the present Dun is a fine long hole. Trying not to be Blimpish and die-hard and to look at the course with eyes unblurred by sentiment, I solemnly and sincerely declare that Mr. Colt made a great job of it. When I last watched a Championship there I might sorrow a little that the course and the greens in particular had taken on something of an inlandish perfection and lacked the old hard and ruthless quality that fought ever against the player, but in point of design Hoylake seemed to me as fine a test of the best modern golfers as was to be seen anywhere in the world.”

Prestwick

“No course has, to my mind, more romantic names then has Prestwick, no, not even St. Andrews. The Alps, the Himalayas, the Sea Headrig, the Cardinal, the Pow Burn-these possess an eternal thrill and I only regret that the Green Hollow, most beautiful of all, is no more. It belonged to the old twelve-hole course, and I have walked with reverent steps to see the site where it once was. I am too juvenile to have seen that old twelve-hole course, for the new ground beyond the wall-the wall is gone now-was taken in the year 1883. It must have been a course of many lovely green hollows, and good as are the newer holes, sterner, longer and more testing, perhaps, than the old ones, I think the supreme fascination of Prestwick is still that of the storied past. The Alps, the 17th with its blind second over the big bunker, may not, according to the most rigid moralists, be a very great hole now; but I, like a romantic idiot, think of it as it was when the bunker engulfed old Willie Park owing to ‘a daring attempt to cross the Alps in two, which brought his ball into one of the worst hazards of the green and lost him three strokes; by no means the first occasion on which he has been seriously punished for similar avarice and temerity.’ Let the modern young gentleman who pitches comfortably home with a number 7 think of that temerous old warrior and feel a little humble.”

“It is the older ground inside the old wall (and I still want on a charger the head of the iconoclast who knocked it down) that makes us love our Prestwick. In his chapter on ‘Some Celebrated Links’Badminton volume, Mr. Hutchinson wrote, ‘We may ask, are not these flatter holes, which we have said to be of somewhat doubtful interest, on the far side of the Himalayas, almost a truer test of golf than those which lie in the dells of the sandhills?’ ; but he did not wait for his own answer, passing on to speak once more of the ‘fascinating uncertainty’ of the older holes. For my part I know that those far holes will test me all too truly, and that there is a most unfascinating certainty about them-namely, that the other fellow will reach them in two bludgeoning shots and get his 4’s, while I do a series of scrambling 5’s. Yet my views are not entirely dictated by selfishness, for when I am watching I always try to stay on this side of the Pow burn, and get some trustworthy person to tell me what happened on the other. in the

If I could, in the manner of William Rufus, steal a tract of country to make my happy hunting ground it is on Prestwick that I should cast my eyes, but my course should be a nine-hole one, stopping at the Cardinal and turning homeward with the Sea Headrig. What a nine-hole course that would be! I and the guests that I should invite to my kingly hunting lodge would enjoy golf of a truly glorious poignancy. But stay! I must reconsider my dream in one respect, because if we turned back after the Cardinal we should not play that terrifying fourth hole edging its way along the burnside, with a bunker exactly where we want to drive, the bunker that once made Taylor, its victim, say that Braid, its designer, should be buried in it with a niblick through his heart. That hole could not be left out. I should therefore have to employ an eminent architect to do my royal pleasure by making me a new hole from the fourth green to the sandhills near the Sea Headrig teeing ground. No doubt, under peril of having his head cut off, he could make me a good one and my course would then be one of 11 such holes as could not be matched in the whole round world. Since, however, this is but a dream, I have to admit that Prestwick is a great, a very great course as it is.”

The famed Alps has already been touched upon, now his thoughts on some of Prestwick’s other outstanding holes:

“The first hole is so good that, as with the first at Hoylake, it is a pity that we have to play it while we are still, perhaps, a little stiff and nervous. The crime against which we have chiefly to be on our guard is that of slicing, for the railway runs along the entire length of the hole on the right-hand side, quite unpleasantly near us. We must not hook either, for rough country awaits the ball hit unduly far to the left, and indeed, the shot is such a narrow one that there are some strong hitters who advocate the taking of a cleek from the tee. The second shot may be described on a calm day as a pitch, and there is a big bunker in front the green, rough ground and a sandy road behind, the railway to the right, and tenacious undergrowth to the left. There is apt to be an engine snorting loudly on the other side of the wall just as we are playing a critical curling putt, and said putt is none the easier from the engine having liberally besprinkled the green with cinders.”

“The third is the ‘Cardinal’, and has done a vast deal of mischief in its time. A topped brassey-shot into the cavernous recesses of the bunker was generally thought to have cost Mr. Laidlay a championship when he played Mr. Peter Anderson; and, to come to later times, it was in this very same bunker that his supporters saw with horror the great Braid trying to throw away the championship in 1908 by playing a game of racquets against those ominous black-boards. Yet, unless the tee be cruely far back, if we can but hit a reasonably straight tee-shot, we ought to send our second flying over the Cardinal’s sandy nob and a good long way on towards the green. Then comes a delicate little pitch over some broken ground, or, if we are lucky, a running-up shot, and we find ourselves on a small green in a setting of hummocks, and should obtain a respectable five; a four is, as a rule, the score of heroes only.”

“One great hole, the fourth. With the wind on one’s back I take this to be the hardest hole in the world. If we slice, the obvious thing to do, we are in the Pow Burn or, at best, in a black-boarded bunker. If we hook-no, not hook, but hit a good shot ever so little too much held up into the wind-plump we go into the bunker on the left, which has caused thousands of execrations to be called down on the highly respectable name of James Braid. If we hit quite straight and lie clear, we have just the same problem for the second-a slice into the burn or a ball held up into the bunker. And of course they-the devilish, impersonal, ‘they’ who do these things-always cut the hole to the left behind the bunker, so that it is hardly possible to get at it. People may talk of the terrors of the Road Hole at St. Andrews, but it is child’s play to the fourth hole at Prestwick with the tee back and the wind blowing half a gale from the left.”

“Now comes the ‘Sea Hedrig’ – a charming hole with a charming name, where the ball must be driven for the distance of two very full shots along a sort of gully or channel between the sand and bents on the right, and some rough and hillocky country to the left. There is narrow little green, with odd corners and angles sticking out and well guarded by hummocks, so that if we do get a four we shall probably have to lay a singularly deft little pitch close to the hole.”

“If a modern architect were to make a hole like the thirteenth he would be lynched by the infuriated members of the club. They would point out that many admirably struck balls are unjustly kicked away to right or left. Perhaps because they are afraid of being lynched few modern architects have ever made a hole as good as Sea Hedrig. I am not even sure that they would allow a blind second over the Alps at a seventeenth hole. I believe they would use the noble mountain as a flanking hazard; but they have never had and never will have the chance.”

Woking

“I find it rather curious to reflect that when I came first to London in 1897 there were but two sandy golf courses for London golfers, Woking and Byfleet. For the rest they had to play on the storied gravel of Blackheath and Wimbledon or upon mud. That is not quite a true statement. Mid-Surrey and Romford existed and though both can be very heavy in winter, it would be unfair to label them as mud. There was also Chorelywood, a most engaging common. The typical and most sought after London course was, however, old Tooting Bec, and that was mud and nothing but it. Yet it had a long waiting list, and men struggled to gain admission to it. I remember it as quite an event when, I think in my second year at Cambridge, I was taken to play on it, much as a young cricketer might feel when making a first appearance at Lord’s. It had some pretty trees and, I think, good greens. When it disappeared into the builder’s maw I do not exactly know, but I have in after days, when driving through the wilderness of Balham, had the spot pointed out to me where once stood Tooting Bec in all its pride.

Woking was in those days still quite new, but it was very good and it is essentially much the same course that it is to-day, though naturally a good deal shorter. I had the good luck to be elected to it at once, under some special rule as to University players, so that I have now belonged to it for thirty years. That was a great piece of luck, since it was by far the best course near London and the waiting list was immense. So long was it, indeed, that when years afterwards the committee had some need for new members, most of those who had waited were found to have died with their ambitions still unsatisfied. It had been founded originally as a Bar club, but this project had been wisely abandoned and select member of the outer world admitted. It still retained, however, a strong legal flavour; the committee sparkled with judges, which presumably accounts for our original lease having been drawn up with singular lack of perspicacity.

Getting to Woking was not then the comparatively simple matter that it is now. First there was the getting early to Waterloo on a Sunday morning. That was not so easy, for there was no tube and comparatively few cabs and these of the drowsiest abroad at such an hour. I lived in the Temple and so could get to the station on foot. Even that was not easy, as anyone will know who has ever tried to walk in nailed shoes upon the granite slabs of unique slipperiness that make or made the pavement on Waterloo bridge. Mr. Wordsworth could never have written his sonnet on that bridge. He would have been wholly occupied in not tumbling upon his nose.

We went in second class carriages with their dear departed red cushions, towards which I still have a tenderness, and got there and back for half a crown. I wish we could now. We were very jovial and friendly for most of the journey, but as we neared Woking station a certain silence and air of hostility fell upon us; we looked to see that our clubs could easily be got down from the rack and that somebody else’s were not on the top of them. Everybody was now our natural enemy to be defeated if possible in the race down the platform. There was a big brake awaiting us and there were also the cabs. It was important to get into the brake, which went faster than the cabs. I had the honour of bringing Mr. John Low down for his first visit to Woking. When the sauve qui peut down the platform began he remarked, ‘It is beneath the dignity of a Scottish gentleman to run.’ So we walked and took the last and slowest cab.

The struggle, however, was not over when the brake was gained. We could not drive up to the Club house, but stopped some way off and walked across a strip of heathery common intersected by ditches, then over a railway bridge, then through a little holly wood and there we were. It was possible to regain lost ground across the heather and to pass several people in the race to the tee. There was one, however, whom no one could pass. This was Mr. Cecil Coward. He always played golf in coat of indefinably horsy cut with voluminous tails. Those tails led the race down the platform, were first into the brake, first out of it, first to scamper across the heather, and the best that one could hope for was to arrive on the tee to see them flying down the fairway to the first hole. I must say for them that they never kept anyone back.”

“Woking has a certain, and almost unique, distinctions-or disgraces, according to one’s point of view-among golf clubs. It has but one medal day a year, and it possesses no bogey. Any innocent stranger visiting Woking and enquiring the bogey score for any particular hole will greeted with a glare of such withering contempt as seriously to impair his day’s pleasure. Another curious, and I think blessed, circumstance about Woking is that the bunkers, which are many and cunningly disposed, are the work of one benevolent autocrat [Stuart Paton]. Unconscious of their doom, the members disperse for their summer holidays and when they return they find that the most revolutionary things have been done. Upon greens that were formerly flat and easy have sprouted plateaus and domes and hollows. Hillocks have risen as if by magic in the middle of the fairway; ‘floral’ hazards bloom at the side, and bunkers have been dug at that precise spot where members have for years complacently watched their ball come to rest at the end of their finest shots. Even now as I write I believe there is a gigantic project in view at a certain hole, which I would rather die than reveal. All these things happen at the instigation of a very small secret Junta, and after a little grumbling, such as is only right and proper, the members settle down and admit that the alterations are exceedingly ingenious and the course more entertaining than ever. It appears to me to be the ideal way in which to conduct a golf club, but it is an ideal that can very seldom be attained.”

“There is one name which must always be freshly remembered in regard to Woking, and that, though he will not thank me for saying so, is the name of Mr. Stuart Paton. I once called him in print the Mussolini of Woking and he did not even thank me for that. No number of wild horses, however, shall prevent me from saying that I do not believe any Golf Club ever owed so much to one man as Woking did and does to Mr. Paton. He has nursed it and cared for it on principles peculiarly his own, and that it is still a place where the most interesting of golf can be played in decency and comfort, without crowding, without time sheets, without Bogey, is in a very large measure due to him. There never was anyone more worthy to be called in the best sense of the words a good golfer.”

St. Andrews

In his 1910 book The Golf Courses of the British Isles Darwin wrote a rather lengthy description of the Old Course, which began thusly: “Really to know the links of St. Andrews can never be given to the casual visitor.” He continued, “I can speak only as an occasional pilgrim whose pilgrimages, though always reverent, have been far too few. I do not know by instant whether or not my ball is trapped in ‘Sutherland’, I only just know the difference between ‘Strath’ and the ‘Shelly’ bunker; I could not keep my end in an argument as to the proper line to take at the second hole-I am, in short, a very ignorant person, who means thoroughly well.”

A very honest admission, however, Darwin was not totally forthcoming. He would later reveal, in the updated version of the same book, The Golf Courses of Great Britain, written in 1925, that when he had written those words he had not been a true believer. “As I come to St. Andrews I find myself in something of a difficulty. It is not that the course has changed, though balls that fly farther and green-keeping that grows better have made a difference. It is I that have in a measure changed since the first edition of this book appeared. Then I wrote ‘as an occasional pilgrim’; and I was by no means altogether a convert to the course. Now I have been there much oftener; I know the course much better and must confess to a far greater, perhaps it may be said a more blind and doting affection. Consequently I have felt bound to alter some of the remarks which I then made, because I do not now agree with them. On the other hand, there is much I might have altered, and have not, because most people go to St. Andrews as ‘occasional pilgrims,’ and may therefore prefer my unconverted views.”

It has been said many times-to the point of becoming a cliché-the notion that one must acquire an appreciation for the Old Course, that the first timer is often disappointed, perplexed as to why it is so highly acclaimed. This phenomenon can actually be observed in Darwin over the years through his writing, a metamorphous from ignorant person to true believer.

BD’s lingering doubts and evolving appreciation are apparent in ‘The Riddle of St. Andrews’, an article from 1913. “For the golfer who only visits them occasionally there is always something particularly baffling and mysterious about the links of St. Andrews. He may think that on his last visit he had really made himself master of them and behold! when he comes back again, he is as much puzzled and as doubtful whether to be angry or enthusiastic as ever he was.”

Darwin then emphasizes the puzzling nature of the bunkers, many which are blind, citing the 12th as a good example of this reoccurring theme. The same hole he completely dismissed in his 1910 book. “The player sees before him nothing but a green and blameless expanse of pleasant meadow land. And yet he knows-or if he does not he will very soon find out-that this innocent-looking plain is absolutely honeycombed with masked bunkers. He has to aim according to his caddie’s directions at some distant spire, without knowing in the least why he is to aim there or how great is the margin of error allowed him, and this is a most disconcerting and difficult thing to do…There is surely no course in the world where it is so hard to learn the right aim.” Darwin goes on to admit it had been many years since he had played the Old Course, and to complicate matters on this occasion he was “handed over to a caddie who was described by his companions as being ‘all right for taking the pin, but a bit soft.’ Consequently on my first round I had to throw myself on the mercy of my antagonists for advice, and these gentlemen, alike admirably qualified for the purpose and having the kindest of hearts, gave directions of diametrically opposite characters, one upholding and the other vehemently denying.” This amusing anecdote illustrates two things: the enigma that is St. Andrews and the limits of BD’s knowledge.

Darwin then gets right to the crux of the matter: “Another riddle which is always apt to bother the returning visitor is, why is it that the course is so good?” He notes the less than sterling 8th, 9th, 10th and the non-descript tee shots at the first and last holes. At this stage of his development Darwin wasn’t able to answer his own question, however a decade later we find he is better equipped.

By this time Darwin had discovered the cliché was in fact reality, that the only way to appreciate the charms of the Old Course was through experience and repeated play, and even then you never really knew the course completely. That was its appeal. “There is always something new to learn about it and a visiting player cannot be expected to acquire in a few rounds the wisdom of the ancients.”

In another article from this later period a well-versed BD explains the process to two confused and unimpressed readers. “About that course golfers so often change their views. They come to pray, remain for a short while to scoff, and then come back again another time to pray forever. The first two steps in this progress my correspondent and his friend followed exactly. They had been warned that they would probably be disappointed, and though they were ‘thrilled on sentimental grounds’ to be there, they were disappointed.”

The correspondent, and his playing partner, asked Darwin to explain why he considered it “‘the supreme golf course.” After their first trip around, these gentlemen found the links had two glaring weaknesses: a lack variety in the holes and far too many ‘small humps.’

“I am afraid my answer to him, since I could not write him a whole essay on the subject, must have proved unsatisfying. One part of it must have been downright exasperating, because I told him that if he went there again and got to know the links better he would probably change his tune. I cited as an example of such change the illustrious Mr. Bobby Jones. Nevertheless, I do not imagine for a moment he believed me, and nothing is more annoying than to be told that you will think differently some day.

This characteristic trait, that most people hate it at first and love it afterwards, belongs in an altogether peculiar degree to St. Andrews; but the question of humps and of sameness of holes is one that may be debated in respect to courses is general.

Admittedly sameness is a defect, and variety a great virtue in courses. Even Mr. Simpson, of the straitest sect of the architects, puts the Alps at Prestwick into his ‘eclectic’ course of eighteen holes. This not because he likes a blind second over a big hill, but because he like variety…I will not give examples of courses where all the holes seem much the same-there are plenty of them; but I do most solemnly protest that St. Andrews is one of them. To be intensely irritating yet again, my correspondent would never cling to that opinion on further acquaintance. Every hole there is cram full of character, and of character subtly diverse.

In the matter of those ‘small humps,’ it is, I think, essential to take, as far as possible, the long and impersonal view. A hump can be rather like a stymie, infuriating to the victim at the time, but interesting from the point of view of the greatest amusement of the greatest number. When we go dangerously near a bunker and the small hump turns us into it, we are naturally incensed, particularly when, as strangers to St. Andrews, we did not know of the hump’s proclivities or even of its existence. On the other hand, when, having further knowledge or better luck, we successfully skirt it or use it skillfully for our own ends, it adds a zest to life and golf.

It seems to me that correspondent’s two main criticisms, as to sameness and humps, both lead to this general question: Is it essential that a course should be easily intelligible to the stranger, or-to put it another way-is it a grave demerit in a course that it wants ‘knowing’? To my mind, the stranger has no right to expect that a course should yield up its secrets to him after the first round or two. They cannot be very exciting secrets if it does. I can remember many occasions on which I have been very cross because, when I had played what I thought was a good shot on a strange course, it turned out to be a disastrous one; but it does not follow that I had the right to be cross; on the contrary, I am, in retrospect, thoroughly ashamed of myself. A course which is perfectly obvious and plain sailing on a first visit-or, as the visitor is likely to call it, perfectly ‘honest’-is not, as a rule, the one that best stands the test of time or produces the most lasting affection among its votaries. In one of those superfluous defences of himself to which he was too prone, Dickens wrote that ‘the peculiarities and oddities of a man who has anything whimsical about him, generally impress us first, and it is not until we are better acquainted with him that we usually begin to look below those superficial traits and to know the better part of him.’ This was not in the least worth saying, as it was said, about Mr. Pickwick; but, as a general proposition, it is applicable to golf courses as well as to men. My correspondent thought the humps at St. Andrews peculiar and odd, and did not like the whimsical things that they did to his ball. I do hope he will go there again and discover the better part of them. I do not yet despair of his becoming a convert.”

We can clearly observe by the end of this process Darwin himself had become a devout disciple, one who believed the Old Course was “the most enchanting, exciting, interesting place to play golf, and especially to play for any length of time.” A mature Darwin shares his insight on why St. Andrews engenders these sentiments:

“When I was in America I was asked by a golfer who had never been to Scotland, what was the difference between St. Andrews and ——-, an ordinary, good, machine-made inland course. I do not remember what I answered, but I am sure I did not make him even faintly understand. What are the characteristics of St. Andrews? First, a profligate generosity on the part of Nature in respect to plateau greens, and incidentally the plateau greens are not like many of those that are elaborately built up for us by the architects, with the ground rising at the back of them; the St. Andrews plateau generally runs away from the player; he is far from having a back wall to help him. Then there is the equal richness in the matter of banks and braes and undulating ground, so that, as a great professional has said in warmest praise, ‘You may make a dashed good shot and get into a dashed bad place.’ Then again there is a remarkable number of ‘dominating’ bunkers which rule the play to the hole. I know no other course on which, if you do not lay your shot down in the right place, an apparently insignificant bunker in your path can make it so utterly impossible to remain anywhere near the hole. As a necessary corollary there is great scope for thought and for taking alternative routes. The course always keeps you thinking, and you must think afresh with every change of mind. Nowhere in the world is golf so little cut-and-dried. Because you make a bad shot it does not follow that you will be immediately punished; very likely you will not; but it is still more likely-it is almost certain-that your next shot will be made exceedingly difficult. You will be able to reach the green, but unless you are very skilful indeed, you will not be able to stay there. There will be a bunker to avoid and you may avoid it, but it will be cunningly reinforced by a slope that will take your ball exactly where you did not want it to go. It is a course of constant risks and constant opportunities of recovering, of infinitely varied and, to the stranger, unorthodox shots, of a certain amount of good luck and bad luck, of very great differences in result due to very small differences in direction. It is occasionally the most exasperating course in the world; it is always the least dull.”

Two Irish Links

Royal County Down

“A fortnight ago I confessed I had once written a description of Newcastle, in County Down, without having seen it. Now I have seen it and I know how lamentably far my imaginary description fell short of the real thing. I should start a fresh and say something of one of the most engaging of all links.

In any description of Newcastle two things play a prominent and inevitable part-Slieve Donard, the noble mountain which looks down on the links, and the almost equally fine mountains of sand on the links itself. Both are at least equal to anything the visitor’s fancy has painted. Slieve Donard is, I believe, some 3000ft. high, and it looks all its height and more because it rises so abruptly from the plain. Its sides are of lovely indeterminate colours, sometimes purple and sometimes brown, which sees to be changing all day as the shadows keep flitting across it. On the second day of my visit, which was very hot, we could first only see Slieve Donard as a towering crest out of a white sea of mist, and all day long it looked vague and hazy. My host tried to tempt me to climb to the top by the statement that all parts of the British Isles could be seen from the top-Northern Ireland, the Free State, the Isle of Man, England, Scotland and Wales. I took his word for it, however, and stuck to the mountains of the links. Various places claim the finest of all golfing mountains; there is Burnham, for instance, and Hayling Island and Prestwick and Dyffryn in Wales, which has, I think, the grandest of all if only they could be fully used. Newcastle can hold its sandy head very high in any such company, and it possesses one beauty which the others have not; heather grows thickly there so that the gold of the sand is splashed here and there with purple. In spite of the Heathery Hole at St. Andrews, we are inclined to connect heather with inland golf, but I shall never do so again after seeing Newcastle.

A course of mighty hills means almost inevitably a course of imposing carriers from the tee, and there are plenty of these at Newcastle. There is, indeed, one sandhill so supremely splendid that it cannot be used because it is too big to carry. As it is, it only makes a background for the third green. My host assured me that when a golf ball was made which would fly a little farther than the present one this hill would be duly used, but he is a person of whimsical humour and his statements are not to be taken too literally. Even without that hill there are plenty of tee shots in which we aim at a white stone on the mountain side and hope to see the ball flying over it into an unknown country beyond; and very fine fun those tee shots are. To my mind, the man who objects to blind tee shots over big hills is in grave danger of being a golfing prig, but it is reasonable to object to too many blind approaches. Now, the blindness of Newcastle is almost entirely confined to its tee shots. I can only remember one approach shot which is for the stranger a dip in the lucky bag; that is at the second hole. It is not a very interesting shot, and it may, as I gather, be altered. Apart from that, if we steer the ball from the tee to the right place, we can always see exactly where we have to go with the second-or third-shot, and have we any right to ask for more?

Besides these drives over hill tops, there are some of those most fascinating tee shots along valleys with the hills threatening on either side, shots which I associate in my own mind with the Lancashire courses of Formby and Birkdale and Blundelsands. We begin with a peculiarly romantic valley at the very first hole, with hills of terrible rough on the left and the seashore on the right; the thirteenth has another equally attractive valley and there are several more of something the same type. Perhaps, however, the most dramatic of all the tee shots is at the sixteenth, where we stand on a high place and see the hole as it seems in the dim distance, with a vast grassy hollow between us and it. When I stood on the tee for the first time I imagined that no human being could possibly reach the green, but in fact the hole is only 230yds long, and an ordinary good drive will get there. The more stern critics may condemn it, saying that there is too much room round the green, that the wild hitter has too much scope; that a strong adverse wind spoils the length, and so on. For my part I think that these austere gentlemen should not have their classic tastes invariably pandered to, and hope that hole will remain as it is, a monument to the cheerful holiday spirit in golf.

The word ‘holiday’ as applied to a golf course may be a double-edged term of praise, and so I ought to add that Newcastle, apart from its palpable jolliness, has some holes as good as can well be imagined, judged by any standard. The third, for instance, might well find a place in any ideal collection of two-shot holes. It has everything that a hole should have-a gorgeous background to the green, rolling broken country and the proper reward for the man who steers his ball to the proper place. If we do the obvious thing and drive right down the middle, we are partially blinded for the second shot, and have a bunker directly between us and the hole; but if we take a risk and go as near as ever we dare to the rough on the left, we can see everything and have a clear run for our money. The ninth, a comparatively new hole, combines spectacular drama and a rich reward for skill in almost equally good proportions; so do the fifth and fifteenth. In short, if there are better courses than Newcastle, there are not so very many, and for a combination of generally lovable and cheering qualities it is in the highest class of all.”