Unraveling the Much-Maligned Dick Wilson

While reams of books and magazine articles have been written to celebrate the “golden age” works of Donald Ross, Alister MacKenzie, A.W. Tillinghast, and C.B. MacDonald, scant information, given his impact on golf architecture, has been written regarding Dick Wilson.

Louis Sibbett (“Dick”) Wilson, was born in Philadelphia, PA, on January 29, 1904. Little is known of Wilson’s childhood, however, many attribute his start in golf came by way of Merion Golf Club, where his father worked as a dirt contractor.

Wilson attended the University of Vermont and was awarded a scholarship for football. He played the quarterback position. In 1924, he joined the golf course design firm of Howard Toomey and William Flynn. Between 1924 and 1925, Wilson worked in the field, (ironically) at Merion once again. Wilson went on to assist the firm at the Country Club, in Cleveland, two clubs in Boca Raton, nine holes at the Country Club, in Brookline, and the renovation of Philadelphia Country Club’s Spring Mill course in preparation for the 1939 US Open. Wilson’s most significant work came at age 27, while assisting Toomey and Flynn at Shinnecock Hills, in 1931.

By the late 1930’s, Wilson moved to Florida and oversaw the construction of Normandy Isles Golf Club, and as well, some touch up work at Indian Creek, in Miami. After the bombing of Pearl Harbour in 1941, lean financial times soon followed once again, post-depression. With little work on the horizon, Wilson took a position as the golf course manager at Delray Beach Country Club and picked up small renovation projects whenever he could. It should be noted that Pete Dye was in his teens when his family took trips to visit Delray, where Pete’s father became friends with Dick Wilson. Soon after, Wilson was drafted into WWII, where he was called upon to construct and camouflage airfields in Florida.

In 1945, Dick Wilson started his own course architecture firm. His first solo work was completed in 1947, at West Palm Beach Country Club.

By the 1950’s, Dick Wilson and rival, Robert Trent Jones, were the most sought after golf course architects in the United States, following the death of William Flynn in 1945 and Donald Ross in 1948. Wilson had 9-10 design and field associates on his payroll and was working on close to 10 courses annually at his peak. The PGA tour held Wilson in high esteem, awarding him the design of their PGA National home course (now BallenIsles), in 1964.

Many experts consider his greatest design and the best example of his work to be Pine Tree Golf Club, in Boynton Beach, Florida. Praise for the course at the time was effusive:

“The best course I have ever seen.” – Ben Hogan

“A truly great course.” – Jack Nicklaus

“The greatest course I have ever played.” – Ruth Jessen

“Dick Wilson’s greatest work of all.” – Gardner Dickinson

In 1964, Wilson was hired once again to renovate the East Course at Merion. Less than 12 months later, Dick Wilson died from a fall at Pine Tree in 1965, where he had a home nearby.

Courses

Dick Wilson designed many significant courses throughout his career. The following are considered his best:

Deepdale Golf Club in 1954. This commission came after the C.B. MacDonald/ Seth Raynor, original course was relocated due to the building of the New York Expressway. Deepdale is one of the most intensely private clubs in America.

NCR Country Club, North and South Course, in 1954. Hosted the PGA Championship in 1969. Both courses are stellar examples of what Wilson could do on a rolling piece of property.

Meadow Brook Club, in 1954. In October of 1955, Herbert Warren Wind, described Meadow Brook as follows, “to my tastes, it is the finest golf course that has been built in this country since Bob Jones and Dr. Alister Mackenzie produced the Augusta National back in 1931. While the course is still much too young for the turf to have taken on body and for the whole 18 to have taken on a final aspect, Meadow Brook has struck me from my first visit on as a “born classic” destined to be mentioned in the same exalted breath with Muirfield, Hoylake, Pinehurst No. 2, Pine Valley and the other acknowledged touchstones of architectural greatness.”

Hole-in-the-Wall, in 1957. Gene Sarazen was quoted as saying, “If I only had one golf course to play, it would be Hole-in-the-Wall.” Course architect, Ron Forse said, “It is one of only a handful of courses in all of southwest Florida with no houses or buildings. Pure golf in a pristine, natural setting.”

Hillwood Country Club, in 1957. Cypress Lake Golf Club, in 1959. Royal Montreal, (3) courses, in 1959. Coldstream, in 1959.

Laurel Valley Golf Club, in 1959. Hosted the PGA Championship in 1964.

Bay Hill Club and Lodge, in 1961.

Doral Country Club, (2) courses, 1962, which includes the famed, “Blue Monster.”

Pine Tree Golf Club, in 1962. Ben Hogan declared Pine Tree, “the greatest flat course in America.” Tom Doak stated, “Pine Tree is the ultimate Dick Wilson layout – longer, flatter, more heavily bunkered and more difficult than most of his other courses.”

Callaway Gardens, 1963

PGA National, (2) courses, in 1964. Hosted the PGA Championship in 1971 and 1987.

Bidermann Golf Club, in 1964. Added 9 holes and lengthened the original Devereaux Emmet design.

Cog Hill, (courses 3 and 4), 1963.

The Club at La Costa, in 1965.

Notable Wilson renovation work includes:

Moraine Country Club, 1955

Colonial Country Club, 1956.

Inverness, 1956.

Seminole, 1957.

Winged Foot (West), 1958.

Metropolitan, 1961.

Aronimink, 1961.

Bel-Air Country Club, 1961.

Columbus CC, 1962.

Scioto Country Club, 1963

Greenbrier, 1964.

Merion (East), 1964.

“A golf course should look more vicious to the player than it actually is. It should inspire you, keep you alert. If you’re playing over a sleepy-looking golf course, you’re naturally going to fall asleep.” – Dick Wilson, 1962, Sports Illustrated

A Brief History Lesson

It would derelict to discuss Dick Wilson’s design philosophy without first acknowledging the state of golf preceding his prime, with the onset of the Great Depression from 1929-1933, another deep recession which encompassed 1937-1939, and lastly, the WWII’s influence on the sport from 1941-1945.

All but the top courses were essentially in disrepair with green budgets slashed, bunkers being filled or left unkept, and once wide fairways began shrinking. To stay afloat, many dropped from eighteen holes to nine. Even top clubs have documented the near and actual bankruptcy during this period. Rationing due to WWII was an issue which lead to the sports further demise, as the New York Times reported, ”gas and rubber shortages reduced play by approximately 50%.” People were simply unwilling to waste gasoline to travel to the outskirts of town, to discover no golf balls were available and no caddies were left to carry their clubs.

“A golf course should look more vicious to the player than it actually is. It should inspire you, keep you alert. If you’re playing over a sleepy-looking golf course, you’re naturally going to fall asleep.” – Dick Wilson, 1962, Sports Illustrated

Another contributing factor to the demise of golf was the massive tax increases of the 1930’s, which cut into the discretionary income of golf’s most ardent supporters. The Revenue Act of 1943, for example, doubled the tax on club dues and initiation fees.

From 1932 to 1952, over six-hundred courses in America closed.

Things changed dramatically in the late 40’s and early 1950’s, as golf’s biggest stars returned from war, economic conditions improved, and America shifted away from the industrial-era, to an economy which allowed more time for leisure activities. America’s appetite for golf was stoked.

Golf equipment took a huge leap forward in both quality and consistency, as rationing for the war effort was halted.Corporations such as Firestone Tire (Firestone CC), Sylvania Electric (Sylvania CC), DuPont (Dupont CC), General Electric (General Electric Athletic Club), IBM (IBM CC), Bethlehem Steel (Bethlehem CC) and the National Cash Register Company (NCR CC – a wonderful 36-hole Dick Wilson design), saw golf as a distinct benefit in recruitment and employee retention, and as such, built full-scale multi-course country clubs, for the sole use of their employees.

The demand for faster greens and better conditioning for clubs also increased, as did the quality of equipment available for golf superintendents. E-Z Go, Pushman, and Club Car began selling golf carts during this period, replacing the golf caddie in masse.

It would be remiss to not include Ben Hogan’s influence on golf’s growing popularity and his impact on course design, as his play and writings of the time suggested a new era of Championship Golf, which demanded greater accuracy and precision, as well as bold strategy, not seen previously. It is no surprise that Dick Wilson was Hogan’s favorite architect.

When asked about shot values, Hogan said, “Playing the right shot into the right area, on each hole. It’s a thinking game, and you have to be able to control the ball.”

Design Philosophy

“A golf course should require equal use of every aspect of the game, rather than make a disproportionate demand on one or two phases, such as driving or putting,” – Dick Wilson

Dick Wilson’s design philosophy was rooted in the strategic, aerial game vs. the preceding, golden age-era architecture, which leaned more towards front-facing greens with wide openings, and run-up shot options.

This was no coincidence, as his early training came under the tutelage of Toomey and Flynn. William Flynn, a transplant from Boston, was part of the ‘Philadelphia School of Architecture’, whose ‘members’ included George Crump (Pine Valley), Hugh Wilson (Merion), A.W. Tillinghast (Baltusrol, Winged Foot, San Francisco Golf Club), George Thomas (Los Angeles CC, Bel-Air), and William Fownes (Oakmont).

Wilson’s green complexes, often raised and set at 30-45 degree angles, were clearly the chief defense of par. From the fairway, the player could easily visualize the challenge ahead, with many of his signature false fronts in plain sight. Wilson was fond of incorporating rear and side fall-offs, concealed by creative, flash-faced bunkering that was often knitted directly into the putting surface. Many of his green complexes contained at least one (front) greenside bunker that guarded the ideal line for players choosing the safe route from which to attack.

Wilson’s fairways were slightly more narrow in width than his historical counterparts, but were by no means considered ‘bowling alleys’. He would often add a fairway bunker (or cluster) that the better player could challenge to gain a distinct advantage and easier 2nd shot, but was careful to leave space for the higher handicap to still enjoy his round. Occasionally, on his more ‘Championship’ layouts, he would stagger fairway bunkers, which added options and visual intimidation for the better player.

Wilson’s chief rival, Robert Trent Jones, favored straight-lined, narrow fairways, that were flanked by bunkers on both sides of the landing area. Wilson liked a little movement in his fairways and was not afraid to add hard dog-legs. Wilson’s greens tended to be sympathetic (not overly done) with interesting interior contours, which could confound players who short-sided their approaches.

While Robert Trent Jones insisted on pushing water features to the edge of his greens and at times, to near-fairway landings, Wilson made use of natural and manmade water surrounds to build up his distinctive green shapes, tee boxes, and to add interest to his already excellent course routings; but rarely made water an integral part of his course strategy, except for a few very select holes. Wilson also loved ‘puzzle piece’ bunkering, which became a signature.

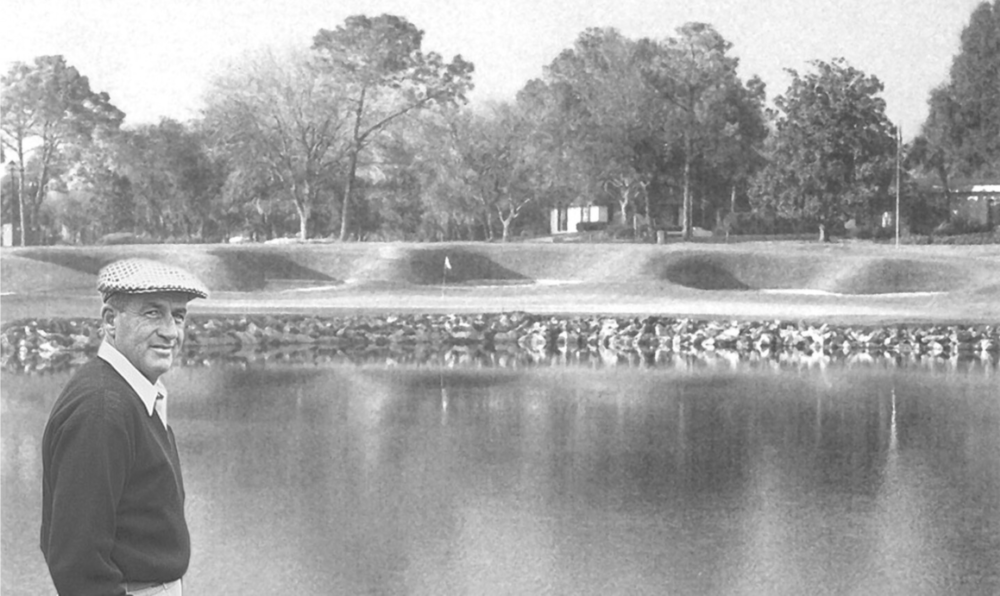

Pine Tree, Boynton Beach, Florida Photo credit: golfproperty.com

While many would consider Dick Wilson’s approach shot difficulty to be on the upper-end of his predecessors, the toughest shot on a Wilson design might well be the 40-50 yard, short-sided recovery.

Being on the correct side of the fairway bares extra weight, given the day’s hole location on a Wilson course; however, the architect did not dictate where (exactly) or how far to hit a drive on his par 4’s and 5’s. Nonetheless, Wilson does ask the player to make a decision on each hole based on the players skill level and risk tolerance – a hallmark of excellent course design. In short, Wilson was very much in favor of a balanced approach to his course design, lamenting the emphasis placed on driving and putting at places like Augusta National.

A study of William Flynn’s design work further reveals the genesis of Dick Wilson’s strategy and course aesthetic:

“Sharp knobs and little bumps and pots are wholly out of place; they do not belong in the picture. A concealed bunker has no place on a golf course because when concealed it does not register on the player’s mind as he is about to play a shot, and thus loses its value. The best looking bunkers are those that are gouged out of faces or slopes, especially when the slope faces the player. They are much more effective in that they stand out like sentinels beckoning the player.” – William Flynn, Golf course architect

Selected Quotes

“After the war, there was a need for golf courses. Mr. Jones figured out how to get them built quickly, Dick was different. He came in wiggling with all his bunkers. It was flat in South Florida, and he would come in and build up the greens and put bunkers in front of them. Dick was a good player, and he made a strong golf course. Dick brought a more severe style, but it was accepted. He did a lot of good work on flat ground in Florida, where you have to be more creative.”

“Few people know it, but all that great bunkering at Seminole, those huge waves of sand that seem to imitate the nearby surf, were the work of Dick Wilson, who revamped the course following WWII. It was one of his early jobs, and he made a pact to keep quiet about his involvement in exchange for healthy fee.” – Pete Dye, Golf course architect (note: Dye’s Father ‘Pinky’ was a frequent playing partner of Dick Wilson at Delray Beach CC)

“He always preached to stay within the history and tradition of the game, but push it out as far as you can. He was doing stuff that hadn’t been seen before. He loved bold expression. If you turned the hole right to left, it was like a speedway; you were high on the right, low on the left.” – Robert Von Hagge, Golf course architect and former design associate of Dick Wilson

“Wilson’s use of tongues in the design of the greens, which provide for more strategic hole locations. I don’t think people could really understand his nuances. His bunkering doesn’t look as intricate as it really is. He was very subtle. The golfer didn’t even recognize why he was being challenged that way. Wilson always made sure it was a golf course you wanted to play over and over again. He’s never really gotten the credit he’s due. Instead, the notoriety has been heaped on Robert Trent Jones, who was a better marketer during his much longer career.” – Rees Jones, Golf course architect

“Where Trent Jones was prolific, Dick Wilson was proficient in that era. Wilson’s courses were overall better, but Jones, the huge greens, and the championship golf, that’s what people wanted. – Ron Forse, Golf course architect

“I enjoy their (Dick Wilson/Joe Lee) golf courses because I feel in control. I think most average golfers find the same comfort in their designs as well. Players arrive on the tee and understand what is asked with regard to shot selection. If they can accomplish the first task, they are rewarded with a clear line of sight or angle on the next. Even on Dick’s most difficult courses, the player never find himself at the mercy of the design without undue cause. The hazards may compound, but only after failure on the first task. The shots, while demanding, are rarely improbable. I think maybe that’s what most understood about the work; the visual aspect gives the player all of the information up front and it’s up to them to hit the shot. In that regard, it’s maybe more player-friendly than the neo-links style of the modern era with super wide corridors, and open green fronts, because the player doesn’t know how to approach the hole without professional guidance or experience.” – Joe Jemsek, Golf course architect

“Dick always liked to have quite a variation in his courses. He designed a lot of tough holes, but he always sprinkled in a few drive-and-pitch holes so the golfer wouldn’t feel like he was playing in a torture chamber. He was especially concerned with the background of a hole, and would move the green in order to take advantage of features that showed it off. He always said a hole should look good from any angle, even looking from the green back down the fairway.”

“Visual appeal serves a psychological purpose. Here in Florida, for example, we go in for high tees. It makes a golfer, feel a little stronger, and it also enables him to see his drive hit, bounce and roll. It gets him more involved in the shot, and for the same reason they try to have the whole green displayed for him on the approach shot. – Joe Lee, Golf course architect and design associate of Dick Wilson

Final Thoughts

History has candidly been unkind to Dick Wilson’s legacy.

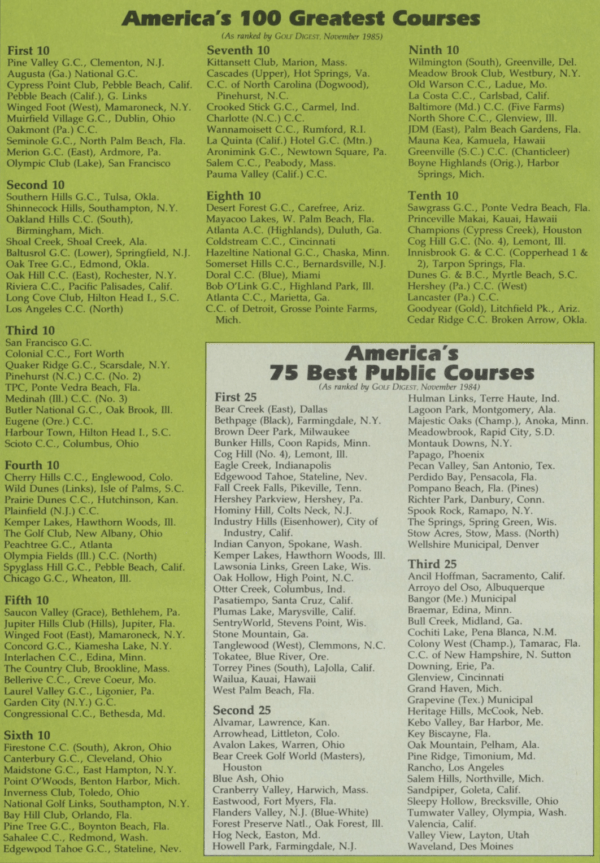

In 1975, for example, Wilson had an astounding (9) original designs in Golf Digest’s prestigious Top 100. In 1985, Wilson once again netted (9) designs with a few juxtaposing positions in the rankings.

Of those courses, none had the land features or views of a Pebble Beach, Cypress Point, or Fisher’s Island. None possessed glorious mountain views, either. PGA National was considered swampland. Doral, another course built on former swampland was dubbed, ‘Kaskel’s folly’, after owner Alfred Kaskel purchased it in the late 1950’s. Bay Hill, Pine Tree, and Hole-in-the-Wall were all built on dead- flat pieces of land; a testament to Wilson’s greatness.

Still today, little is known about his design philosophy or the number of future architects Wilson undoubtedly influenced?

Would we, for example, have a Pete Dye strike out on his own during his mid- thirties, without Pete’s father’s countless rounds at Delray Beach CC with Dick Wilson?

Would Jack Nicklaus’s design philosophy and course portfolio be radically different, had Robert Trent Jones and Dick Wilson not been competing head to head for the better part of ten years, considering both men’s divergence from ‘Golden Age’ design principles?

What about architects like, Arthur Hills, whose courses have never made a top 200 list, but nonetheless has created many fun, albeit challenging, public and private courses, members have enjoyed for decades? Could Wilson have inspired him to create bolder, more difficult designs than what most of his contemporaries in the late 1970’s-1980’s produced?

Could Dick Wilson have built more golf courses in his day, given the lack of competition and the quality of his work? Certainly, however, Joe Lee and others who knew him personally have commented on Wilson’s insistence on being involved in both the construction and design of his courses, in comparison to Robert Trent Jones, who leaned more heavily toward’s the sales and promotion side.

Lastly, what caused Dick Wilson courses to fall out of favor with Golf raters and the public?

A few theories (based on common sense and a little research):

1. Wilson’s most notable courses were softened or altogether changed over the years. Arnold Palmer radically altered Bay Hill and Laurel Valley. Wilson’s design associate, Joe Lee, softened countless original Dick Wilson courses after his passing, to the point of indistinguishable except in routing. Doral and La Costa, two of Wilson’s highest ranking courses, today have no Dick Wilson left.

2. Green committees. Nothing ruined great architecture in the 1950’s and 60’s more than the overzealous and frankly, ignorant armchair architect’s of the time who went on mass tree planting sprees. Coldstream is a perfect example of a great Dick Wilson original, that over time became an arboretum, due to the radical work of uneducated committee’s looking to toughen up their courses. How many of Dick Wilson’s signature ‘puzzle piece’ bunkers have survived the board room?

3. The ‘Minimalist’ movement. The return to golf’s roots in the early 1990’s dubbed the Trent Jones/Wilson-era the ‘dark ages’. Bulldozers were mostly eschewed. Renovations on Donald Ross courses were birthed. Seth Raynor, who only .0005% of the golf population had heard of, was being re-discovered once again. Trees were the enemy. Mega-width became a rallying cry.

4. The Developer movement. Course routings stretching across what used to be unfavorable land became ideal for placing neighborhoods in Anytown, USA during the 1970’s-early 2000’s vs. a walkable Dick Wilson. And who could blame the developers for understanding how to get top dollar for a home? Plastering Fazio or Nicklaus’s name in a magazine was a sure-fire way to sell out a subdivision, architecture be damned.

5. His courses were viewed as ‘too demanding’ for the average golfer. Trends in golf go back and forth. In the mid-1950’s through the 1970’s, hard, tight golf was right. After the Tiger boom, softer, more aesthetic features became en vogue. Nicklaus, Dye, Trent Jones, and Mike Strantz, have all had to come back at one time or another to soften their courses. The difference regarding Wilson? Even his middle-tier courses have become unrecognizable versus his contemporaries.

6. Wilson has been (unfairly) lumped in with Robert Trent Jones. Even in his prime, Robert Trent Jones courses were widely viewed as, “too tight, too tough, and too unfair” for regular golfers. A careful study of Wilson’s actual work reveals a compromise between ‘golden age’ principles and that of the “hard for hard’s sake” ethos of RTJ.

To be fair, until I accidentally drove into the parking lot of Cypress Lake Golf Club in Fort Myers, Florida in early 2021, I had written Dick Wilson off as little more than a 2-3 hit wonder. I had fond memories of a tournament ten years ago at NCR and had driven into Coldstream and Cog Hill to look at a few holes, but outside of those experiences, I had thrown Wilson into the same indifferent cubby hole as Trent Jones (although Trent Jones has not had his courses altered with near the ferocity of Wilson).

With more rounds (now) under my belt at a handful of re-touched Dick Wilson gems, I can clearly make the case for a second look at an architect I feel more would appreciate. It is especially pleasurable to note that one rarely loses a ball on a Dick Wilson-designed course. His courses are routed for ease of walking, as many of his green-to-tee walks are short and fit nicely with the flow of the round.

So where does all of this leave Wilson’s legacy? That’s for the player to objectively decide. For me personally, I enjoy walking his fairways as much as I do the Ross and Raynor clubs where I have logged many more rounds over the years. I’ve heard it said many times, ‘the best courses are ones that you immediately want to play again’. For me at least, Dick Wilson checks all of the boxes.

“You can put a beautiful woman in an expensive dress, but if the dress doesn’t fit, neither the woman nor the dress is going to look any good at all. It’s the same with building a golf course. You got to cut the course to fit the property.” – Dick Wilson

Bibliography

https://www.shinnecockhillsgolfclub.org/history

https://www.deepdalegolfclub.com/history.html

The Architects of Golf, Geoffrey Cornish and Ron Whitten

The Confidential Guide to Golf Courses, Tom Doak

The Evolution of Golf Course Design, Keith Cutten

Feed the Ball podcast, Episode 31(Joe Jemsek) and Episode 80 (Ron Forse), Derek Duncan

Golf and the American Country Club, Richard J. Moss

Golf Digest, February 1981, Ross Goodner

Golf Digest, December 1997, Nick Seitz

Golf Digest, June 1989, Ron Whitten

https://web.archive.org/web/20131031114707/http://157.166.226.103/golfonline/ travel/architects/wilson.html, Brad Klein

https://reader.golfdigest.com/2020/05/08/quantum-leaps/content.html? utm_campaign=programmarketing&utm_medium=onsite, Mike Stachura & E. Michael Johnson

https://www.golfcoursearchitecture.net/content/robert-von-hagge-light-and-shade, Adam Lawrence

https://www.golfpass.com/travel-advisor/articles/the-original-forgotten-golf- course-architect-of-arnold-palmers-bay-hill-club-lodge, Brad Klein

https://vault.si.com/vault/1962/07/02/golfs-battling-architects, Sports Illustrated Staff

https://www.golfdigest.com/story/gw20090209sherman, Ed Sherman

https://vault.si.com/vault/1963/08/26/where-is-the-golf-course-of-the-workers, Sports Illustrated Staff