New Discovery Opens Shot To Medinah’s Future

by Daniel J. Lane

with contributions by J. Ryan Potts

December 2020

Does this 1939 aerial show the essence of Tillinghast’s work at Medinah?

Long renowned as an exemplar of the “penal” school of golf design, Medinah Country Club’s Course #3 has just as lengthily been on the receiving end of punishment from fans of golf architecture. In his Confidential Guide for example, golf architect Tom Doak called the course not only a “maximum-security prison,” but also wrote that the course lacked “strategic challenge” and discouraged “finesse play.” But while the foundation of Course #3’s reputation is usually believed to have been present from the course’s birth in 1930, new evidence found by former University of Illinois golfer, architecture enthusiast, and Medinah member J. Ryan Potts suggests that Medinah’s story may be more complex than anyone has thought. Within the Medinah everyone is familiar with, there may be an older, wilder course that has not seen the light of day since Pearl Harbor—one whose design may in fact have been influenced by the Wizard of Winged Foot, A.W. Tillinghast.

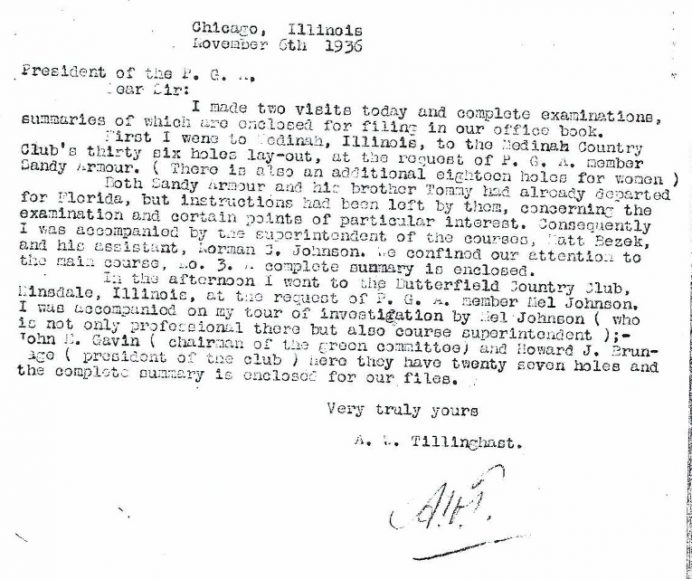

Provoked by a presentation that alluded to the possibility of a Tillinghast connection by newly-formed architecture firm Ogilvy, Cocking, and Mead (OCM)—recently hired to create a master plan for the legendary course—Mr. Potts inquired of the famous architect’s appreciation group, the Tillinghast Society, for material relating to Medinah. That inquiry unearthed a letter dated 6 November 1936 to the president of the PGA of America from Tillinghast, designer of Winged Foot West, Bethpage Black, and many other courses widely admired both for their strategy and toughness. In the letter the architect reports having been invited to visit by Sandy Armour—brother of Tommy Armour, the long-time head professional at the club—to perform a “complete examination” of the course, as well as to investigate “certain points of particular interest.” That examination, the letter says, is summarized in another document, which has unfortunately disappeared. Just what it contained is tantalizing, however, due to the next find.

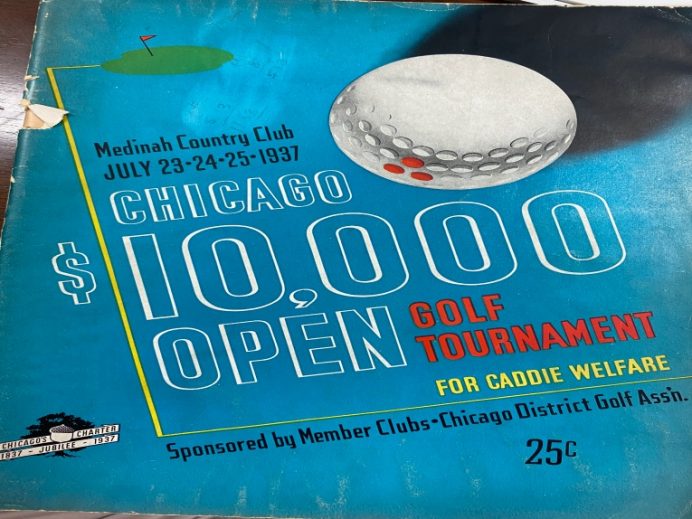

That discovery is a program for the Chicago Open held at Medinah July 23-25, 1937. The golf course on display in that pamphlet is hardly that of the lengthy bruiser familiar to golf fans. Instead, on view is a wide-open routing very different from the long familiar bowling-alley-in-a-forest recalled by most golf fans. The bunkers are free and wild with tendrils extending everywhere, and are very far from the composed structures visible today. They are, in fact, reminiscent of other Golden Age courses—courses very like those designed by A.W. Tillinghast.

Did the Bully of Bethpage have a hand in Chicago’s own brute or was this, as has been widely believed, simply Tom Bendelow’s best work? The photographs, reproduced below, are suggestive of Tillinghast’s work elsewhere, including Winged Foot. In contrast to the tree-lined narrow fairways that gave Medinah its fearsome notoriety and have often defined the penal school of architecture, the photographs depict a windswept landscape dominated by grass, not forest. Far from symmetrical greens pour across their settings, seemingly at random. Bunkers appear to lurk everywhere with shapes, position and scale unlike those built on Medinah’s lesser known sister-courses, #1 and #2.

Reminiscent in its vastness of the original twelfth at Beverly Country Club, the 2nd hole one-shotter presented a different angle and no bunkers in 1937.

Today at hole 3, the righthand bunker has been tucked into a corner, but in 1937 it extended far into the fairway.

Unlike 1937’s bunkerless 2nd hole, the 1937 version of the 4th was replete with bunkers nearly everywhere on the approach, and is considerably narrower than today. Undoubtedly that forced aerial approach to an elevated green increased the score-wrecking probability of “going long.”

Enormously wider than today, in 1937 the 5th fairway led to what now would be called an ‘infinity’ green.

Instead of today’s elevated green with a narrow chute to allow access, the 1937 version of the 7th featured a wide mouth very receptive to running chips and pitches.

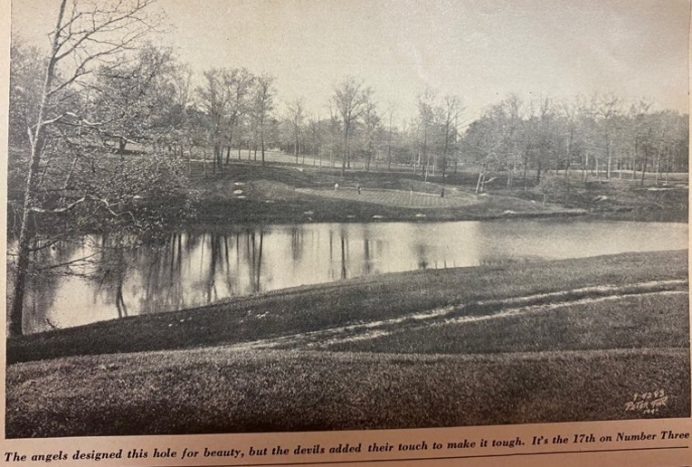

Unlike the holes remarked here, the essential challenge of the seventeenth (lucky thirteen in today’s routing) remains largely unchanged, though there is the hint of a false front on the left.

Unfortunately, that course however appears to have disappeared sometime in the 1940s, likely perhaps due to the exigencies of the Second World War. The club’s own history makes reference, for example, to sheep grazing the course during the emergency, as the able-bodied who might otherwise have been mowing Medinah were instead mowing down the nation’s enemies overseas. After the war, as golf historians know, the “Silver Age” of golf course architecture prevailed, rewarding straightforward ball-striking ability at the expense of cunning. From that perspective, the U.S. Open at Medinah in 1949 may have been a turning point in architectural history away from the Golden Age and towards the new style.

Yet, while the possibility of a Tillinghast connection might excite golf historians, the more significant question for golfers generally is what it means for Medinah and, perhaps, the game itself. Medinah has, after all, always prided itself for rewarding those who drive the ball long and straight—exactly the sort of golf currently embodied by Bryson DeChambeau, winner of this year’s U.S. Open at (you guessed it) Winged Foot. But a player as powerful as DeChambeau may be demonstrating the absolute limits of that approach to golf: following that line to its limit, as DeChambeau appears to be doing, suggests a game that may as well be played on a computer simulator as on real courses. The recently-discovered trove of photographs, then, may represent not the road not traveled for Medinah—but a “line of charm” to the storied club’s future.