‘Sair Fecht’: the 16th hole at Highlands Links

by Jeff Mingay

By the time golfers reach the sixteenth tee at Highlands Links, they’ve encountered what have been recognized by golfing authorities as three of the world’s best par 5s:

-

- the picturesque 532 yard sixth, played alongside the marshy mouth of the Clyburn River, emptying into the Atlantic Ocean;

- the demanding 570 yard seventh, aptly dubbed ‘Killercrankie’ by its legendary architect, Canadian Stanley Thompson; and,

- the spectacularly scenic 548 yard fifteenth, with its rolling fairway plunging toward the coastline, providing dramatic views out to sea.

Yet, it’s the relatively unheralded 460 yard sixteenth that seems to provoke the adventurous spirit in the golfing purist most of all Highlands Links’ three-shot holes.

Thompson gave all eighteen holes at Highlands Links Gaelic names. He called the sixteenth ‘Sair Fecht’, which translates as ‘hard work.’ Indeed, the sixteenth is a hole that must have required some really hard work back in 1941 when Highlands Links opened for play and the ball didn’t travel nearly as far, nor as straight, as it does today. Still, in this modern age of titanium club-heads and solid-core balls, the sixteenth remains one the course’s most interesting holes.

The walk from fifteen green to sixteen tee is one of Highlands Links’ legendary treks between holes – about 200 yards or so, I guess, across a highway, past St. Peter’s Church and its adjacent cemetery, then up a small hill from atop which golfers get their first glimpse of the sixteenth’s bunkerless yet boldly contoured fairway rising some fifty feet up a hillside. High in the distance, swaying with the ever-present seaside breeze, is the flag.

From the elevated 16th tee, the ravine to the left and the yellow flag on the green are evident.

The sixteenth green is the highest point on the course. On clear days, looking back toward the tee, golfers are provided spectacular views of Ben Franey – the mountain that presides over Highlands Links and shares its name with the first hole – the adjacent par 4 second, and just beyond it, the Atlantic.

The tee shot at sixteen is relatively straight-forward, played over a flora-and-fauna-filled ravine into a wide berth of fairway. The only driving hazards – a dense forest on the right and a steep drop-off at left – are peripheral. But of course, the massive fairway contour at sixteen can be hazardous too, and is difficult to avoid.

According to golf architect and historian Geoffrey Cornish, who supervised the construction of Highlands Links during the late 1930s, Thompson put a great deal of thought into the creation of the fairway contours at sixteen. He meticulously orchestrated the placement of piles of rocks and boulders cleared from the hole corridor, then covered the piles with riverbed silt excavated from the area comprising the sixth fairway – a construction method that caused serious problems for the irrigation contractor when Highlands Links’ first fairway watering system was installed in 1996.

Like most holes on the course, there are very few, if any, ‘flat’ spots at the sixteenth aside from the tee. The right side, which is the most direct route to the green, is particularly humpy and bumpy. There is however a ‘flattish’ areain theleft centre of the fairway, some 230-240 yards off the tee. But golf balls rarely find this spot today. Since the introduction of fairway irrigation, balls tend to ‘stick’ on uphill, downhill and sidehill lies rather than collect in lower, ‘flatter’ areas as they more often did in day’s gone by. Perhaps this phenomenon is an equalizer of sorts, providing a short par 5 with some additional challenge in the face of an ever-improving golf ball? After all, the second shot at sixteen becomes that much more challenging from an awkward lie.

Level lie or not, accomplished golfers, like Highlands Links’ long-time professional Joe Robinson, almost always go for the sixteenth green in two nowadays. Fashioned with a few small rolls, it’s a relatively flat green without a single bunker defending it. But there’s a steep drop-off immediately to the left to penalize wayward approaches. From down there, some 12-15 feet below the level of the putting surface, a blind pitch must be played over a steep grassy bank into the shallowest portion of the green.

No more than two-putts are generally required at sixteen, unless the wind is blowing hard, effecting equilibrium. And it often does.

For the majority of golfers more inclined to lay-up at sixteen, the principal hazard is yet another steep, grassy bank some 60 yards short of the putting surface in the direct line from tee to green. Laying-up too close to this bank leaves a completely blind third. Thus, the prudent play is to keep back about 100 yards or so from the green in order to have a look at the top half of the flagstick.

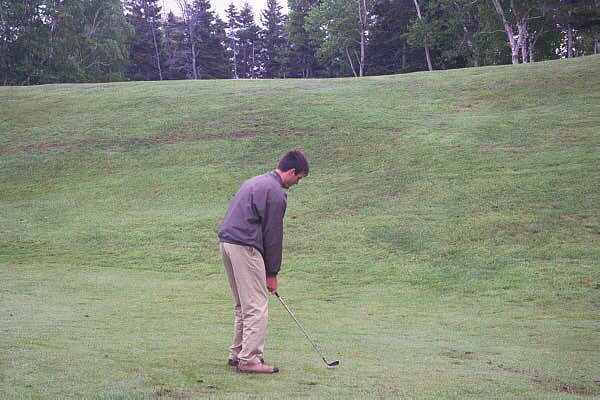

Having laid 30-40 yards back from the grass bank, Jeff has a fine view of the flag.

From the base of the grassy bank, Jeff can no longer see the flag.

Still, the sixteenth green is deeper than it is wide, so even with a partial view of the pin, it’s difficult, if not entirely impossible, to decipher where the hole is actually cut – front, middle or far back? – making for an interesting third.

In the old days, the aforementioned bank was covered by gorse bushes. Not only did the gorse present a very serious hazard to contend with, it must have added some beautiful texture to the sixteenth hole. Reportedly, the gorse bushes were eradicated decades ago because golfers were losing too many balls amongst them. Strange, considering there’s ample room to have avoided the gorse using some intelligence. The sixteenth fairway is more than 50 yards across.

Cornish doesn’t recall the gorse being part of Thompson’s original plan for the sixteenth hole. He suspects it was planted after the architect had finished his work. Nonetheless, it would be very exciting to see the gorse restored someday – to return yet another distinctive feature to one of the game’s most unique holes.

The End