In My Opinion

The Early Architects:

Beyond Old Tom

by

Thomas MacWood

June 2008

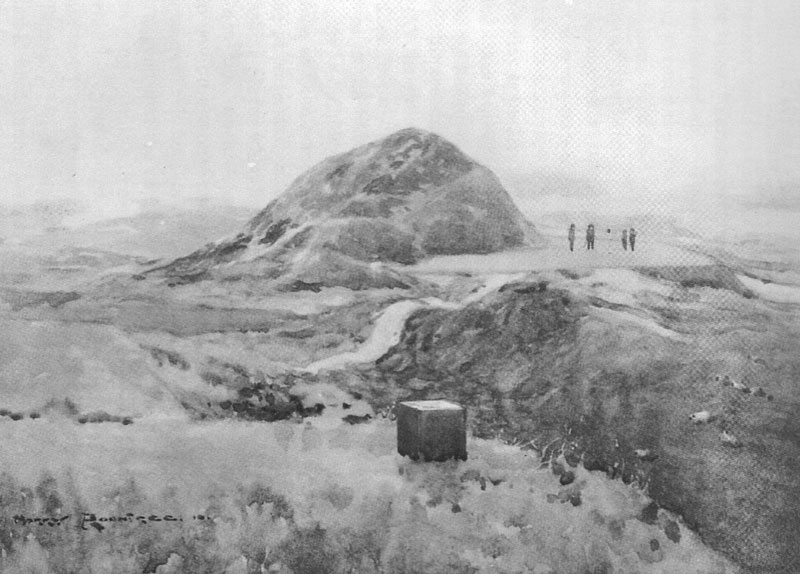

The Postage Stamp at Troon.

Most of us are stubborn by nature. Once we get an idea in our head its very difficult to remove it, at least that has been my experience. In contrast to this human nature a good researcher should strive to keep an open mind when approaching their subject, and for the better part of a year my subject has been the golf architecture of the 19thC, unfortunately when I began my mind was hardly open. Just the opposite, I entered with a predisposed and frankly poor opinion of the golf architecture of this period. My view had been formed by the likes of Colt, MacKenzie, and Simpson, who dismissed the era, going so far as to call it the Dark Ages. Because of their harsh treatment I had always thought the nineties were a wasteland, and as a consequence focused my energies on the so-called Golden Age. However ignoring the nineties proved to be difficult. While researching the more acclaimed age I continually came across references to this apparently unrefined period, and as I dug further I found many of the leading figures of the good years were either products of that previous era or influenced by men from that era. It became clear the two periods were linked, and in order to fully understand the Golden Age I had to better understand the earlier period, and so I set out to learn what I could.

Early on in the investigation what struck me was the sheer amount of activity, especially in the 1890s. The game’s popularity exploded in these years, and as a result there was great demand for new golf courses. Reports of new courses inundated magazines and newspapers, and as I made note of these courses a group of names surfaced as the primary designers. Some of the names are well known to us today, men like Tom Morris, Tom Dunn and Willie Park-Jr, but there were other names-Charles Gibson, Peter Paxton, B.Hall Blyth, and James McKenna as examples-that were unfamiliar. I concluded that the key to uncovering the truth would be found through these men.

Another surprising discovery, in contrast to what the critics implied, not everything created by these early architects was bad. On occasion they produced very good work, and sometimes historically significant work. In fact some of our most acclaimed courses trace their origins back to this period. I am not suggesting Simpson and the others were entirely wrong, it is true this period and these early men produced their share of average to below average designs, but there were notable exceptions.

This led to an obvious question – why was there such a disparity? When analyzing the good and bad results a fairly simple formula emerged. In virtually all the examples of good design the golf architect started with good material, usually near the sea. When they were given less than perfect land the results were often disappointing. The early architects had little or no capacity to improve what they were given. But despite these limitations a number of early designers stood out, not only for their good work, but also the influence they had upon those who followed.

If I may digress at this point, and explain my motivation for writing this essay. I had planned on writing about this subject at some point but had no immediate plans to do so, in fact I had moved on to another project. This changed when I learned of Melvyn Morrow’s fine essay ‘The Early Golf Designers: The Real Golden Age.’ When I first read the title understandably I was interested in his thoughts and how his conclusions might compare to my own. Based on the title it appeared we shared a similar view-that history had ignored important 19thC contributors. However as I read the essay it became clear his focus was different than my own. MM is justifiably proud of his great, great grandfather’s historic accomplishments, and without question Old Tom is a most deserving subject, but presumably, at least based upon the title, the essay was meant to celebrate the early golf architects not just Old Tom. Unfortunately, once again we find the others virtually ignored, and not only are they ignored, Old Tom’s architectural record is inflated at their expense. It was time to give these men their due.

Category One – The Amateurs

I have segregated the architects into two categories – amateur and professional. You will find one or two familiar names among these amateurs but the majority are unknown. Their anonymity is not surprising since the typical amateur was involved in only a handful of courses, if that, and in many cases just a single course. Despite their limited activity it is important we recognize these gentlemen, not only for their outstanding designs, but also for the example they set for the amateurs who followed, men like Fowler, Macdonald, Abercromby, and MacKenzie. While compiling background information on these men a similar profile began to form: good amateur golfers, well educated, successful professionally or inherited wealth, and like so many of their era, multiple interests.

Dr. W. Laidlaw Purves – William Laidlaw Purves was born at Edinburgh in 1842, the son of a physician. Purves was educated at Edinburgh University. In contrast to his father initially he turned to law, but then had a change of heart, and while employed in a lawyer’s office began to study medicine. His parents died during these years and at the age of 19 Purves found himself a ship’s doctor operating off the coast of Australia. After three years in Australia he returned to Europe and continued his medical studies at Universities in Berlin, Leipzig, Vienna, Utrecht, and Paris. After his European educational tour he eventually settled in London as a consulting aural surgeon at Guy’s Hospital. Purves had a most successful medical career, becoming ophthalmic and aural surgeon at the Hospital for Diseases of the Nervous System and aural surgeon at the Aural College and Academy for the Blind.

Dr. Laidlaw Purves

Medicine may have been Purves’s vocation but golf was clearly his passion. He learned the game on the Bruntsfield Links in golf crazed Edinburgh but found a very different situation when he arrived in England. There were but four golf clubs of any note in the entire country – Westward Ho!, Hoylake, Blackheath and Wimbledon. The first two were far from his home in London, and the latter two were nearby but poor substitutes for the real thing. For the next nine years Purves searched Greater London for a perfect site on which to build a golf course. Epping, Epsom, the downs from Reigate to Farnham, Windsor Forest, Bushey, Richmond Park were all prospected. At Epsom he actually marked out a Sunday course in 1875.

The coastal areas within reach of London were also surveyed. Purves inspected the Isle of Wight, New Forest, Southampton, Littlehampton, and Bognor. In 1876 Felixstowe was examined, and a golf course laid out. But Felixstowe was not completely satisfactory, in fact none of the sites were satisfactory, that is until he discovered Sandwich in 1877. Finding the perfect site was only half the battle, for the next several years Purves tried to convince his fellow golfers that the property held amazing potential and they should help finance the project. Finally in 1883 he had generated enough interest to make an offer to secure the land, actually he made four offers, unfortunately all failed. At last in 1887 an offer was accepted, a lease secured and a syndicate of 36 formed. Purves proceeded to lay out the course, and St. Georges was born.

The course immediately drew universal praise, and not long after became a fixture of the Open and Amateur Championships. Although some of the quirkier aspects of the early course are now gone, like the Maiden and Haides, its bones remain very much as Purves originally made them. One must also give credit to Ramsey Hunter, the club’s first professional, who helped to formalize the layout. Purves’s success at Sandwich led to another opportunity in 1888, when at the request of the proprietors of land on the coast near New Romney, he laid out Littlestone. Purves died in 1918 at Hartwick Cottage, his home and one of the oldest residences in Wimbledon.

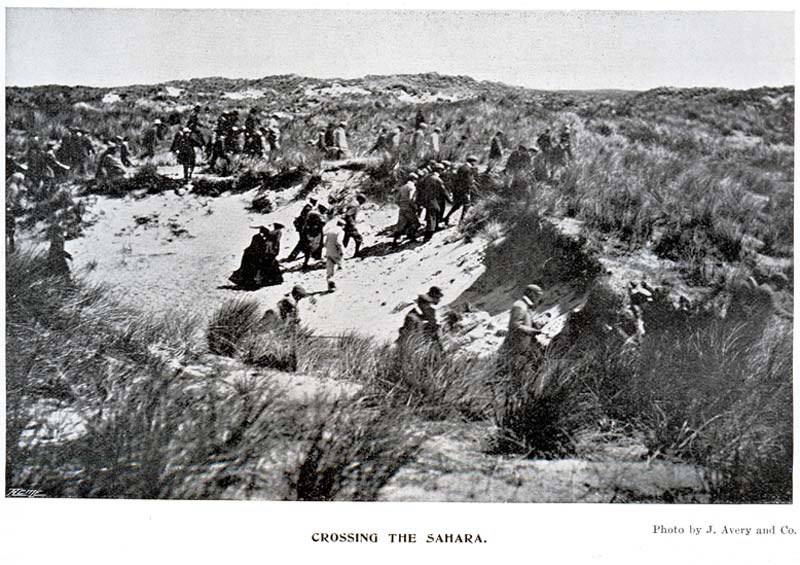

St. George’s opened to great acclaim, thanks to its wild hazards directly in the line of play such as the Sahara at the old third hole and…

…and the monster Hades bunker at the old eighth.

B. Hall Blyth – Born in Edinburgh in 1849 Benjamin Hall Blyth studied at Edinburgh University before joining the family engineering firm in 1867. His father, the senior Benjamin Hall Blyth, founded the firm of Blyth & Cunningham, which eventually became Blyth & Blyth (a prominent firm to this day). Hall Blyth like his father before him became one of the best-known civil engineers in Scotland. As the consulting engineer for the Caledonian, North British and Great North of Scotland Railway Companies he was involved in the design and construction of a large numbers important works, including the North Bridge and the Waverly Station in Edinburgh. He was also responsible for extending the North Berwick rail line to include stations at Aberlady, Luffness and Gullane. Blyth was elected the president of the Institute of Civil Engineers in 1914, the first Scot to have such an honor. In addition to his engineering activities he was President of the Scottish Football Union in 1875 and 1876 – BHB had been a prominent rugby football player as a young man.

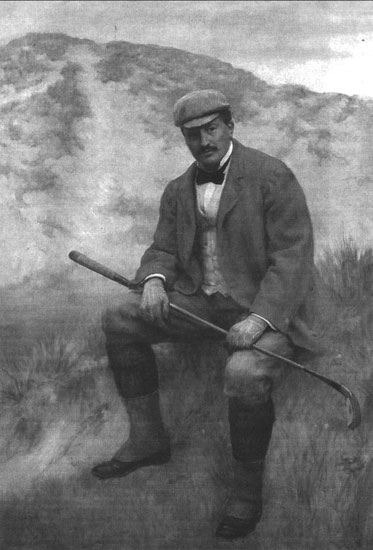

B. Hall Blyth

Benjamin Hall Blyth played his early golf at North Berwick, the family home Kaimend House overlooked the famous Redan hole. As an adult he was a long-time member of the Royal and Ancient Club, Captain of the Honourable Company of Edinburgh Golfers in 1880-81, Captain of the Royal Liverpool Club in 1885, and Captain of Tantallon Golf Club from 1896-98. Despite this impressive resume Hall Blyth was only an average golfer, although he did defeat Willie Campbell in 1880 in one of the more bizarre matches in history, a cross-country affair that began at Point Garry, North Berwick and ended at the High Hole at Gullane. “Campbell opted for the shore line and played over North Berwick, Archerfield and the ground that eventually became Muirfield, before reaching Gullane. Hall Blyth elected to play on an inland route through Dirleton and although longer this was a much simpler course. Hall Blyth won easily over the six mile distance and his opponent came early to grief on the rocks.”

Hall Blyth was a powerful voice within both the R&A and the HCEG. He was one of the primary forces behind the creation of the Amateur Championship. He pushed for the formation of the new Rules of Golf committee in 1897, and not only was one of the original 15 members of that committee, he was appointed its chairman. BHB is also credited with securing the transfer of the Honourable Company of Edinburgh Golfers from Musselburgh to Muirfield.

In ‘Muirfield and the Honourable Company’ author George Pottinger describes this extraordinary man: “Hall Blyth served continuously on numerous committees concerned with Golf clubs throughout East Lothian and he usually got his way. A tall powerfully built man, he had a loud voice in which he boomed confident opinions and defied challenge. He wore a Dragoon’s moustache and affected something of the air of a marinet. To see him, attired in checks almost as loud as his voice, referee a championship match and hear his resonant ruling was said to be unforgettable.”

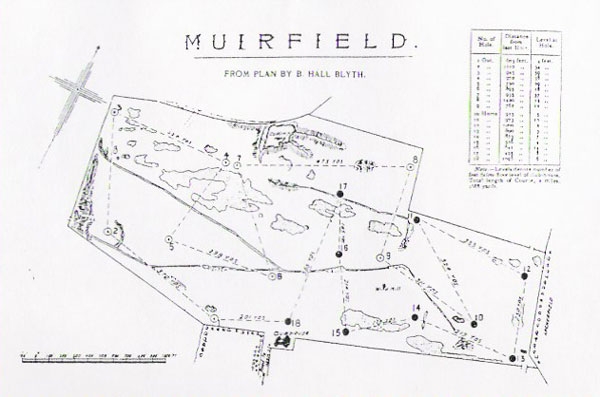

A drawing based on Blyth’s 1891 plan for Muirfield.

For many years Old Tom Morris was thought to be the architect of the New Course at St.Andrews however the R&A and Links Trust now recognizes Hall Blyth as its creator in 1895. His formal plan is thought to be the first draft plan to use centerlines to indicate the proper path to the hole. His involvement with the New should not have come as a complete surprise, he had been heavily involved in the new layout at Muirfield in 1891 (along with Old Tom). Early reports mention his name prominently during the design and construction phases of Muirfield. The Honourable Company minutes of April 1914 confirm his important involvement: “On the motion of the Captain it was unanimously agreed to record in the minutes the club’s heartiest appreciation of many services rendered by Mr. B. Hally Blyth in connection with acquisition and preparation of the course at Muirfield,” Remarkably he also designed Muirfield’s clubhouse. In addition to his design work, Hall Blyth was chiefly responsible for the acquisition of Braids Hill for the citizens of Edinburgh. Benjamin Hall Blyth died in 1917 at the family home overlooking the links at North Berwick.

The foreign correspondent Henry Leach wrote this amazing tribute in American Golfer:

“Mr. Hall Blyth was sixty-eight years of age, and a life member of the Royal and Ancient Club. Being an engineer by profession he could not help applying some of his engineering and constructional instincts to golf courses. Probably he was the first real golf course designer. Until he turned his attention to the business, which is now pursued ardently and thoroughly by many persons, golf holes were to a large extent made themselves, as it might be said. Nature, the lie of the land, suggested the places where putting greens should be made, the places for teeing, and the main route to the hole. In course of time it might happen that a number of persons who were agreed upon the point, such as the committee of a club or society that played upon the ground, would dig a hole for a bunker at a spot where it was considered there should be some punishment waiting, but this sort of thing was very sparsely done, for it was considered and generally found that Nature made quite enough trouble for the golfer. It was more or less in this way that most of the famous holes on the old courses came to be made, such as those of St. Andrews, North Berwick and other places, though in latter times bunkers were added according to carefully arranged schemes. But Mr. Hall Blyth considered that fine holes might be made without waiting for the slow evolution from Nature, and he set himself about the design and construction of such holes at St. Andrews itself, North Berwick, Muirfield and Gullane, and on these famous greens there endure testimonies to his fine imagination, great golfing judgment, and skill as a designer.”

S. Mure Fergusson – Born in Perth, Scotland in 1855 Samuel Mure Fergusson spent his formative years at St. Andrews. Ironically he did not take up golf until comparatively late in life, late that is for a lad in St. Andrews, he was fourteen. His father managed an insurance company in London, and acordingly time was split between north and south. His early golf on the Old Course was played with Tommy Morris, David Strath and Leslie Balfour-Melville. At the age of twenty Mure Fergusson was elected a member of the R&A, and proceeded to win the Autumn Medal in his first competition. In all he won twenty medals, the last one coming thirty-nine years after the first. Fergusson was twice runner-up in the Amateur championship, losing close matches to John Ball and FG Tate respectfully. He was fourth in the 1891 Open Championship at St.Andrews and might well have won had his putting not failed, the strongest part of his game. Not only did Fergusson compete at a high level he was also one the game’s most effective administrators, being a member of numerous committees including the inaugural Rules of Golf Committee of 1897. S. Mure Fergusson was captain of the R&A in 1910.

S. Mure Fergusson

Mure Fergusson was a successful stock-broker in London and as such played most of his golf in England. In the early eighties he was connected with Felixstowe but when Sandwich opened he migrated to that club. In 1895 he laid out a golf course on the estate of HF Locke-King, the pioneer in aviation and motoring. This was the New Zealand Golf Club at Blyfleet, and it was an unprecedented design being the first golf course carved out of a thickly forested property. Fergusson was New Zealand’s long time secretary, and in that capacity was regularly improving the course. Fergusson went on to design a nine-hole golf course for King Edward at Windsor and Duff House Royal in Scotland with Archie Simpson.

In 1906 Mure Fergusson contributed a chapter in Horace Hutchinson’s Golf Greens and Green-keeping-sharing his expertise on making a course out of a pine forest. It began, “To anyone who has been accustomed to play golf on a seaside course the idea of making a links in a pine forest seems, to say the least of it, a curious one. But when one thinks the matter out it is not so peculiar, for most pine forests grow on sand, and for a golf links sand is a sine quo non, at least from my point of view.” Later he describes how to construct a proper bunker, and can not resist taking a shot at golf architect’s favorite punching-bag, “Nothing to my mind, is more abominable on a golf course than the awful zarebas that used to be erected by poor Tom Dunn and others who first laid out inland greens.”

Zarebas? Merriam-Webster says they are improvised stockades native to North Africa, another in a long line of military allusions found in golf architecture’s lexicon. Mure Fergusson died in 1928 at his beloved New Zealand Golf Club.

H. Mallaby-Deeley – Harry Mallaby Deeley was born in London in 1863. His father William Clarke Deeley was a prosperous oil merchant. Harry was educated at Cambridge, and went on to become one of the most successful and daring real estate dealers at the turn of the century. “When the idea of acquiring any particular property had occurred to him he would follow it up with an interview with the owner, and usually, if the latter had the least intention of disposing of his interest, Mallaby-Deeley would come from the meeting place with a half sheet of notepaper recording the proposed contract.” That is how is he settled the purchase of Covent Garden with the Duke Bedford for the staggering price of just over £1,750,000 ($15,000,000). Similar sums were paid for the purchase of properties at Piccadilly Circus and Founling Estates.

H. Mallaby-Deeley

HMD was an avid golfer who played to a scratch at Prince’s Golf Club, Mitcham Common. Mitcham was designed by Tom Dunn in 1892, and was considered nondescript and ordinary. Mallaby-Deeley became the chairman of the club in the late 1890s and proceeded to overhaul the course. When he was done it was considered one of the better inland courses in the Kingdom.

Infected by the architectural bug Mallaby-Deeley then set his sites on a seaside property where he envisioned a modern links. His dream was to create The super course-a golf course incorporating all the theories of modern golf architecture. It had long been rumored the Earl of Guilford’s estate at Sandwich possessed some of the finest golfing ground in England, and there were several attempts to induce him to sell but he had always declined. In 1904 after a long negotiation HMD was finally able to purchase the 360 acre property.

Mallaby-Deeley then set out to make his dream a reality. Initially he consulted an impressive collection of experts, including Horace Hutchinson, HH Hilton, John Low, Cecil Hutchison and Herbert Fowler, and then proceeded to lay out the course with the assistance of Charles Hutchings and PM Lucas. It opened 1906 and was immediately recognized as a groundbreaking design. Princes was Britain’s version of the National Golf Links three years prior to the NGLA opening for play.

Princes was an incredibly well thought-out design for its day featuring big bold hazards.

Princes was Mallaby-Deeley’s last known excursion into design, but despite his limited activity Josiah Newman editor of the American magazine Golf in 1914 called Mallaby-Deeley “the finest amateur golf architect in the world.” He died in 1937 at his chateau at Cannes, but not before donating Princes, Mitcham Common to the public.

John Sutherland – John Sutherland was born in 1864 the son of a Dornoch shoemaker. He began playing golf at 14 and was admitted to the club three years later, making scratch at once. Sutherland was appointed secretary in 1883 – a position he held for an amazing 58 years. Sutherland first competed in the Amateur Championship in 1891 at St. Andrews, and was a consistent attendant for the next 20 years. If there had been a prize for distance traveled most years he would have won it.

John Sutherland

No one knows precisely when golf began at Dornoch, records indicate the game had been played there as far back as 1630. We do know the ‘modern’ game came to Dornoch in the 1870s with a nine-hole golf course. The Dornoch Golf Club was officially founded in 1877. In 1886 Old Tom Morris was engaged to layout a proper golf course, staking out a new nine thus extending the course to 18 holes. Sutherland carried out this work over the next few years. Old Tom deserves credit for getting things started but without question Dornoch was Sutherland’s long term project. Throughout his tenure he continually improved the courses including a major redesign in 1904, which included extending the ladies course to 18 holes.

In 1902 Golf Illustrated wrote of Sutherland: “He has given great service in laying out and altering, not only his own green but many of those in the neighbourhood.” Sutherland was invited in 1891 by the newly formed Brora Golf Club to layout a nine-hole golf course. He returned to Brora in 1902 and extended the links to 18 holes. That same year he laid out Skibo a private course for none other than Andrew Carnegie. In addition to Carnegie’s private course Sutherland designed and built private golf courses for the Duke of Portland at Lanfwell, the Duke of Sutherland at Dunrobin and Mr. Eric Chaplin at Stoer.

Sutherland taught the game to future professionals Donald Ross, Alec Morrison and Tom Grant, and this quote from The Scotsman may indicate which pupil he favored, “John Sutherland I know was proud of the Dornoch boys who carried the fame of his native town across the Atlantic.” One wonders what impact he may have had upon Ross the golf architect. As a young man Ross was both an apprentice to a building contractor and one of the best amateur golfers in the region. Members of the club urged him to go to St.Andrews to learn club-making, however his family wanted him to continue in the trade of carpentry. When the club promised to make him their professional, his parents consented and he was off to St. Andrews and Forgan’s golf shop for a brief apprenticeship. From 1893 to 1899 Ross was Dornoch’s first professional and presumably worked closely with Sutherland, who acted as the club’s secretary and greenkeeper (Sutherland was a self-taught expert in agronomy whose advice was sought throughout the UK). It is difficult to say to what extent Sutherland influenced Ross but it appears at the very least he laid his foundation.

In addition to his club responsibilities, John Sutherland was the Town Clerk, and beyond his public duties he advised Lord Rothermore and WT Tyser of Gordonbush on financial matters. He was also a successful Estate Agent. Sutherland even found time to write the golf notes for The Daily News, and contributed several articles to Golf Illustrated. Through his writing Sutherland was largely responsible for publicizing this islolated gem, and as a result the course attracted an impressive list of pilgrims including the Newton, Joyce and Roger Wethered, John Low, JH Taylor, Ernest Holderness and others. John Sutherland died suddenly at his home Golf View in 1941.

A.M. Ross – Alexander Mackenzie Ross was born in Edinburgh in 1850. His father made Venetian blinds for a living. One of the most famous of the old school Scottish golfers AM Ross was raised on the doorstep of the historic Bruntsfield Links. “It is said in St.Andrews that babies are toothed on golf clubs. Though born in Edinburgh, Mr. Ross’s aptitude for the game found almost the same fostering circumstances, for in boyhood he lived on the verge of Bruntsfield Links, and there, before he had reached his teen, he had become something of a prodigy.”

A.Mackenzie Ross

Had there been an Amateur Championship in those days it is difficult to believe he would not have been one of the first holders. When the Championship was eventually instituted in 1886 he had little time to devote to the game due to business interests. Ross was the most successful exhibition caterer and refreshment contractor of his day, and held the exclusive contracts for the International Exhibitions of Edinburgh (1886), Manchester (1887), Brussels (1888), and London (1891). He was also the proprietor of the famous Café Royal Hotel in Edinburgh.

MacKenzie Ross was a member of the Edinburgh Burgess Golfing Society, and for many years was considered almost invincible over Musselburgh links. He was also a frequent medalist at North Berwick, Gullane and Luffness. Ross won over one hundred medals during his golfing career (They are currently on display at the clubhouse of the Burgess Golfing Society at Barnton).

Later in life Ross was fortunate to have a good deal of leisure time, and this he spent in enjoyment of the game. In addition to playing the game Ross was keenly interested in golf course design. In fact his son, future course designer Phillip Mackenzie Ross, claimed his father was the first to coin the term golf architect. The elder Ross’s first taste of design appears to have come just prior 1890 when he and his friend Colonel Baird discovered Mildenhall and laid out two holes on the property of William Gardner. Eventually a club was formed and in 1891 Tom Dunn was brought in to extend the course. He pegged out 18 holes, however before construction commenced Ross convinced the principals nine holes would be preferable since Dunn’s eighteen was to utilize unsuitable marshy ground. Ross remained closely associated with Worlington and deserves a great deal of credit for what many consider the best inland course built prior to 1900.

In a twist of the Worlington situation Mackenzie Ross was involved with another famous nine-hole course when in 1893 he proposed Musselburgh be extended to 18 holes, and went so far as having the ground surveyed. In the end his proposal was rejected. In 1897 Ross was captain of Luffness New when a group of members broke away to form Kilspindie in 1898, and he along with Ben Sayers designed the new course. From 1898 to 1900 Ross was in charge of the committee that oversaw the construction of the second course at Gullane. Willie Park-Jr. had originally laid out the course but a disagreement over his fee resulted in the termination of that relationship. PM Ross claimed his father was involved in the design or redesign of Royal Burgess at Barnton Gate, Murrayfield and New Luffness.

Ross apparently enjoyed his boyhood home adjacent the Bruntsfield Links for in 1894 he acquired a villa overlooking North Berwick, and in 1904 built the impressive Hill House situated a top Gullane Hill with panoramic views over Luffness, Kilspindie and Gullane Links. A young PM Ross’s first foray into course design occurred at Hill House, when he designed a miniature golf course on land adjacent to the formal garden. AM Ross died in 1915 at Gullane Hill House.

Horace G. Hutchinson – Born Horatio Gordon Hutchinson in London in 1859, the son of General William Nelson Hutchinson. In 1860 the family relocated to Devon when his father was appointed commanding officer of Government House. It was at North Devon (Westward Ho!) that a very young Hutchinson was introduced to the game by his uncle, Colonel Hutchinson, one of the club’s founders. After studying at Oxford, Hutchinson went to London and began to read for the Bar, but before being ‘called’ he had second thoughts, and spent the next several months traveling through Europe. He did not touch a golf club for an extended period and claimed he had to ‘relearn’ the game on his return. Evidently he relearned well for he won the Amateur Championship the first two years it was held in 1886 and 1887.

Horace Hutchinson – the grandfather of golf course architecture

HGH used those championships as a springboard to his writing career, a very successful career that ultimately led to him becoming in essence the voice of the game. Bernard Darwin wrote, “In the early eighties golf was, save in a few places, comparatively little known in England, and Mr. Hutchinson, alike by his fine play and his pleasant writing, did a great deal to increase the popularity of the game. Indeed, it is hardly too much to say that at one time golf to the Englishman was represented by two names, those of Mr. Horace Hutchinson and Mr. Arthur Balfour.”

Hutchinson’s first known architectural involvement came in 1888 after his father moved from Devon to Eastbourne in Sussex. A local man requested HGH lay out a course which became Royal Eastbourne. The downland course was known for two attributes: the cavernous ‘Chalk Pit’ and wild greens. Darwin wrote, “To putt at Eastbourne is an art of itself. It is not that the greens are not good, for they are excellent, but the hidden slopes in them are extensive and peculiar.” That same year Hutchinson claimed to have laid out one of the first golf courses in America for the Rockaway Club in 1888. He toured the United States in 1887 and 1888.

Without question Hutchinson’s masterpiece was Royal West Norfolk (Brancaster)-collaborating with Holcombe Ingleby in 1892. A prideful Hutchinson remarked, “its distinguishing features are the absence of artificiality and the great variety to be found in the holes.” He would go on to design Isles of Scilly (1904), Harewood Downs (1906) with JH Taylor, and Le Touquet (1904) in France, in conjunction with Taylor and Willie Fernie. He also assisted in the redesign of Ashdown Forest where his friend Jack Rowe was the professional. Hutchinson lived in a cottage adjacent to the course. In addition to these projects he was involved in the formation of several new clubs, including Burnham & Berrow, Nairn, and numerous clubs around London. In all he was a member of a mind-boggling 300 golf clubs, and certainly his expertise in architectural matters would have been a benefit to all.

Brancaster’s lack of artificiality has helped make it a stand-out course for well over a century.

Although his design accomplishments are impressive unquestionably his greatest contribution came by way of the pen. In the 1890s he was a regular contributor to numerous magazines, most notably Golf magazine, often discussing aspects of design within its pages. An example of his forward thinking is illustrated in this excerpt from 1897, “Raynes Park itself is a pleasant and interesting course in the summer, but its soil is of very clayey nature, and in consequence becomes almost unplayable in the wet weather. But the country about Woking is all of that light, almost sandy soil in which rhododendrons and Scotch firs especially love to grow. This is, of all inland soils, the kind that gives the best golf, and its characteristics are those that the prudent prospector of a golf course in Great Britain, in America, and all the world over will first look for. Provided the soil is light-such at least is our experience over here-all things are possible, no matter what the growth or what sterility appears on the surface of the soil.”

A chronological look at Hutchinson’s architectural writing begins in 1890 with Golf from the Badminton series-one of the first and most widely read books on the subject. It touched on every aspect of the game including golf course development. That was followed by Famous Golf Links — published in 1891 — the first book profiling the great golf courses of both Great Britain and Europe. It was collection of articles he had written for The Saturday Review. In 1897 Hutchinson joined the staff of the new periodical Country Life as its first golf editor and almost immediately began commenting on new golf courses, emerging golf architects, and architectural theory. That same year he edited the remarkable British Golf Links – the striking photo essay that remains our best documentation of early golf. His next effort was The Book of Golf and Golfers, written in 1899. It included a chapter on “laying-out and up-keep of greens” written by Mssrs. Sutton & Sons, with supplementary remarks by Willie Fernie. In 1906 Hutchinson edited the first book devoted to the science of golf-architecture and maintenance — Golf Greens and Green-Keeping. Among the contributors were HS Colt, WH Fowler, S. Mure Fergusson, James Braid, CK Hutchison, Peter Lees and HH Hilton. Hutchinson was a guiding force not only for the game, but also for these men who would contribute so much to golf architecture.

Hutchinson’s last book relating to architectural matters was his golfing memoirs – Fifty Years of Golf – written in 1913, though not published until after the War. That same year he had very serious operation that almost killed him. He ultimately survived but was physically limited and in considerable discomfort the remainder of his life. Golf was over forever, as was his influence upon the game. The suffering ended in 1932 when he took his life, jumping from the roof of his four-story home at Lennox Gardens, Chelsea. He was 73 years of age.

Other amateurs – I would be remiss not to briefly touch on these other prominent amateurs golf architects.

Robert Chambers, Jr. was born at Edinburgh in 1832, and the son of Robert Chambers the famous publisher and author of Vestiges of Creation. He followed his father into the publishing business in 1853 and in 1873 became editor of Chamber’s Journal, which he ran with great success. Chambers was a fine golfer who grew up playing over the Old Course but in later years played mostly at North Berwick where he had a second home. In 1878 he won the inaugural Grand National at St. Andrews, the precursor to the Amateur Championship. Although not as prolific a writer as his father Chambers did manage to write one of the first books relating to golf – A Few Rambling Remarks on Golf. He also co-authored (with his father) the famous poem ‘The Nine Holes of the Links’ of St. Andrews, which appears in Robert Clark’s classic book, Golf: A Royal and Ancient Game. Chambers’ lone architectural accomplishment was laying out the first nine-hole course at Hoylake with George Morris in 1869-no minor accomplishment. Robert Chambers died at his house in Edinburgh in 1888.

Rev. AT Scott was born in 1848 at Cambridge where his father was vicar. A good athlete and avid sportsman, Scott was involved in the historic Oxford-Cambridge cricket match of 1871. In 1886 he became the vicar of St.James, Turnbridge Wells. In 1888 he was a founder of Royal Ashdown Forest, and laid out that famous golf course. Royal Ashdown Forest features a total absence of artificial hazards since the original charter of the Royal Forest prohibited man-made alterations to the land. Scott remained at the club his entire life, and was the Archdeacon of Turnbridge at the time of his death in 1925.

Henry Hope of Luffness in East Lothian was born in 1839, and educated at Eton and Christ Church College, Oxford. Henry Hope was the landed proprietor of Luffness House and it adjoining 3200-acre shire. Luffness had been in control of his family since the 18thC. In 1865 Hope laid out the first 18-hole golf course between Edinburgh and London. This was the old Luffness, which he built at his own expense with the help of Old Tom Morris. Sir Alexander Kinloch said, “Mr. Hope was very kind to lay out this course for them, but he did not see where the people were going to come from to play it.” They came, and they came in large numbers, and when in 1893 old Luffness moved to another site, Hope laid out Luffness New on his estate. The next year he asked Old Tom Morris to advise on the placement of hazards however the layout remained essentially Hope’s. Henry Hope died in 1913.

CJ Gilbert was born at New Romney, Kent in 1859. He began his professional life as a solicitor, but later became an electrical engineer and manager of a chemical works. Ironically he was best known as an amateur expert in geology, specializing in the occurrence of sand and gravel deposits. Who better than an expert in sand and gravel to dabble in golf architecture? His only known architectural work was the design of the nine-hole course at Berkhamsted in 1890. The site featured heather, bracken and the ancient Saxon earthworks known as Grim’s Dyke. Like Ashdown Forest there were no man-made bunkers.

George Combe was born at Belfast in 1862 and educated at Rugby. Combe was the consummate sportsman excelling in cricket, football, billiards and golf. He was also one of the pioneers of motoring in Ulster. Another in a long line of electrical engineers turned golf architect, Combe was a founder of the Irish Golfing Union in 1891, and for many years its Honorary Secretary. His status with the Union led to several design opportunities including the lay out of the first nine at County Sligo in 1895. Without question his greatest design accomplishment was transforming Royal County Down into one of the world’s great golf courses. That transformation began in 1900 and continued for the better part of a decade. Combe died at Lisburn, Northern Ireland in 1938.

George Combe

WC Pickeman was born at Montrose in 1868, the son of the administrator of the Royal Lunatic Asylum. As a young man Pickeman was an insurance clerk in Edinburgh – playing his golf over the links at Musselburgh. He moved to Dublin in the early nineties taking a position with the Law Union and Crown Insurance Company, eventually ascended to managing partner. His architectural career began on Christmas Eve 1893, when he and fellow Scot George Ross rowed over to the peninsula of Portmarnock in search of land for a possible golf links. Boating in late December? I suspect Christmas cheer was involved. Whatever the case they found the site perfectly suited, and made a proposal to the landowner Mr. Jameson, the famous distiller, who being a good Scot himself, and an avid golfer, consented. Nine holes were laid out by WCP in 1894, and the full 18 were in play two years later. It should be noted Pickeman wisely sought the advice of Mungo Park (Old Willie’s brother) in this early stage. Pickeman went on to design/redesign an estimated twenty golf courses, including Castle, Skerries and Kilmashogue. He also inspired a group of Dubliners who went on to their own distinguished design careers: Cecil Barcroft, Peter Gannon and AV Macan. WC Pickeman died in 1931 at his home in Dublin.

HS Colt was born in 1869 at Highgate, London. Colt studied at Cambridge where he captained the golf team. In 1893 he joined a solicitors office in Hastings. As one of the leading amateur golfers in England understandably the Rye Golf Club sought his advise when planning their new links. Ultimately Colt and Douglas Rolland (who Colt knew from Malvern) laid out the golf course. Those two were also involved in the redesign of Hastings-St. Leonard the following year. The inclusion of one of the most successful golf architects in history may seem a bit odd, but one must remember his professional design career would not commence for another twelve years. For that reason Colt is a good example of the amateur architect from the early period.

Category Two – The Professionals

Now we move on to the professionals. It was a very simple relationship, as the popularity for the game increased there became a demand for two things “ golf equipment and golf courses, and the early profesional architects could deliver both. In fact in most cases club-making was their primary profession. Creating golf courses was seen as a means of expanding their equipment market, and the quicker the better.

Tom Dunn “ Born in 1850 at Musselburgh Tom Dunn was the son Willie Dunn, who along with his twin brother Jamie Dunn played a series of historic matches with Allan Robertson and Old Tom Morris. Tom Dunn’s early life was spent at Blackheath in London were his father was custodian of the links. In 1864 Old Willie and family returned to Scotland taking a position at Leith. Tom remained at Leith until 1870 when he moved to North Berwick to start a club-making operation. Later that year he was appointed professional of the London Scottish Club at Wimbledon, and occupied that post for eleven years. In 1882 he returned to North Berwick taking charge of the links. This lasted until 1889 when he returned to London and the Tooting Bec Golf Club. It was during his tenure at Tooting Bec that the game’s popularity exploded in the south, as did the demand for new golf courses, and Tom Dunn was poised to meet that demand.

Tom Dunn

In 1902 Tom Dunn wrote, During the particular period I was at Tooting Bec I laid out a great number of golfing greens; a well-known golfer called it the “Dunn Era.” I cannot remember them all just now, but here are some: Furzedown Tooting [Tooting Bec], Mitcham, Sudbrooke Park, and the Old Deer Park at Richmond, Stanmore, Northwood, Enfield, Eltham, Woking, Rayne Park, Norbury, Balham, Bude, Fonthill, Buscot Park, Petworth, Staunton Harold, Steningford, Bedstone Court, Fan Court, Ganton reconstructed, Sheringham, Frinton-on-Sea, Skegness, Deal, Brighton extended, Hastings, Beckenham, Bromley, Welbeck Abbey, Dinard and Coubert in France, Shireoaks, Bulwell Forest, Surbiton, Hurlingham, Brooke, Ventnor, Taplow, Cork, Weston-super-Mare, Kingsdown, Landsdown at Bath, Ashley Park, Walton-on-Thames, Babraham, Hincksey Marsh at Oxford, Worlington, Soham at Newmarket, and the reconstruction of Littlestone and Seaford; and some in France, and Oratava in the Canary Islands, etc. In all I have laid out 137 golf links.” Others he did not recall include Felixstowe, Great Yarmouth, Chorleywood and Hayling.

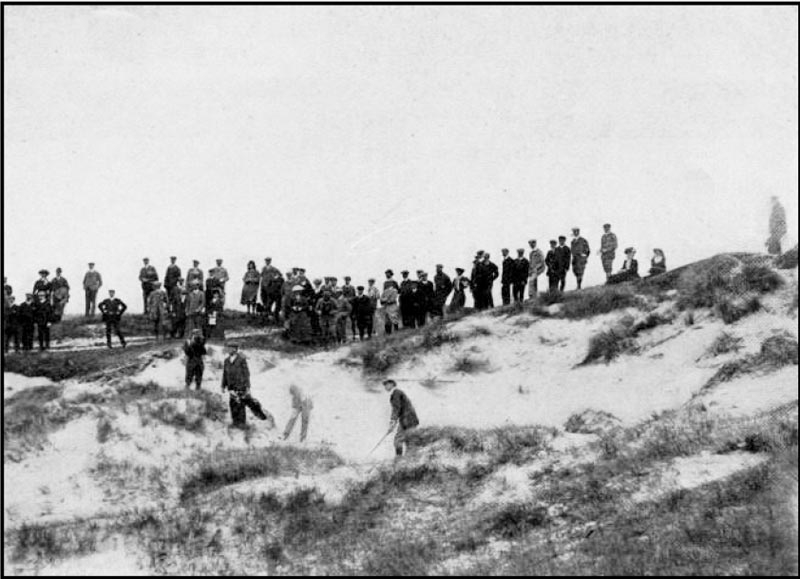

Dunn’s greatest talent as an architect may have been his ability to route eighteen consecutive holes in an appealing manner. Sometimes, his architectural features such as these cross hazards at Bournemouth didn’t stand the test of time.

In 1895 Dunn was approached by a group from Bournemouth who were interested in building a golf course and an adjoining resort. He was given three sites to evaluate and chose Meyrick Park. Tom Dunn wrote, “Nothing appeared on the surface of the land but heather, furze, and pine wood; but with 100 men, twenty horses, and a scarifier, short work was soon made of this wilderness, and the links was completed in three months. It cost £2500.” Dunn was appointed greenkeeper and professional, and remained for five years. During that time he designed nearby Broadstone on another heathery property. He considered Broadstone the best design of his career.

Near the end of his stay at Bournemouth Dunn’s health began falter, and in 1899 he went to America to recuperate. His son John Duncan Dunn, a noted golf architect himself, was working in Florida at the time. During his six month stay TD claimed to have laid out several golf courses including one near the Tampa Bay Hotel. When he returned to England he designed Hanger Hill, where he remained as professional and greenkeeper until a bout with consumption forced his retirement. He died at the Blagdon Sanitorium, near Bristol, in 1902. The Edinburgh newspaper The Scotsman had an interesting take on his mercurial career, “Tom’s career was rather much that of a rolling-stone, which was due to his own weakness, and not to the desire of any of the clubs which employed him to dispense with his services.”

Tom Dunn was the target of criticism after his death (the critics were mostly silent while he walked amongst them). After reading these later accounts one could easily conclude “Poor Tom Dunn” was his given name. Men like Colt, Campbell and Mackenzie when analyzing the 1890s singled him out as the symbol for Victorian golf architecture and all the evils it represented. And without question he was guilty of the formulaic use of cross-hazards and the hit and run method of staking out a course. Make no mistake, that was his modus operandi. On the other hand he was providing an important service at a time when no one really knew what they were doing. As Horace Hutchinson wrote, “It was a simple plan, nor is Tom Dunn to be censured because he could not evolve something more like a colourable imitation of the natural hazard. A man is not to be criticized because he is not in advance of his time.” One wonders if his formative years spent at Blackheath â€and not at Musselbourgh â€had a detrimental affect. Whatever the case he should at least be given partial credit for those courses that ultimately turned out well, like Woking. Certainly others were involved in polishing those courses but he did conceive their structure and should be credited at the very least for their initial routing, the foundation of all good architecture.

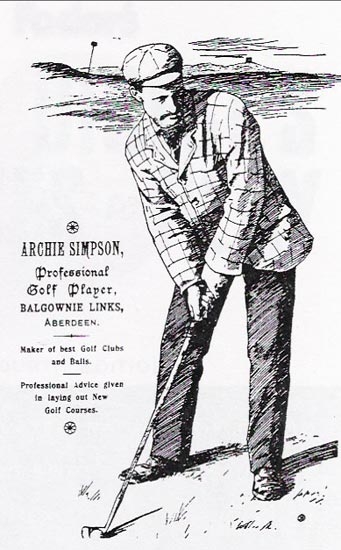

Archie Simpson “ Born at Earlsferry, Scotland in 1866, Archie Simpson was the son of a linen weaver. There were six Simpson brothers who played the game well, three of which were well known in golfing circles. Jack Simpson won the Open championship in 1884, and became the pro/greenkeeper at Elie. Robert Simpson was in charge of Carnoustie and a respected club-maker. Robert was also involved in golf architecture, including the redesign of Carnoustie and the design of Panmure, both assisted by Old Tom Morris. But of all the brothers Archie was the most famous and the most gifted. He was twice runner-up in the Open; won the first golf tournament at Sandwich (defeating Douglas Rolland in extra holes); and won numerous money matches, including a thrashing of Willie Park-Jr over Musselburgh and Carnoustie.

Archie Simpson

Simpson began playing the game at an early age on the links of Elie – winning prizes in local competitions when little beyond school age. At age fifteen he had the remarkable accomplishment of coming in with the lowest score of the day in a club match at St. Andrews. Even at this early age he displayed the power and long driving that became his hallmark. Archie was just eighteen years of age when he became a professional, joining his brother Robert at Carnoustie. In March 1891 he went south, taking the head job at Bembridge, Royal Isle of Wight, but by the end of the summer he was back in Scotland working with Charlie Hunter at Prestwick. His stay at Prestwick was short lived as well. He returned to Carnoustie in late 1892, setting up the company Robert and Archie Simpson Clubmakers.

The reasons for Simpson’s sudden movements are not known, but one often finds a woman behind such erratic behavior. We do know Archie married around this time, his wife Isabella Low Simpson was from Carnoustie (sister of George Low of Baltusrol fame, and future architectural partner of AW Tillinghast and Herbert Strong) and they had their first child in 1893. Late in 1894 Archie was on the move again, becoming the professional at Aberdeen, Balgownie “ a course he and his brother Robert designed in 1888. Here he finally settled down, remaining at Royal Aberdeen for 16 years. This would be his most productive design period.

Regarding Simpson’s design career as mentioned his first project was Balgownie in ’88. In 1896 Simpson laid out Stonehaven and Dufftown. Then came Cruden Bay in 1899, arguably his greatest architectural achievement, although you wouldn’t know it today since the club recognizes Tom Morris and not Simpson as its original designer. Multiple contemporaneous reports gave credit to Simpson although in March of 1899 The Times, when announcing the course’s opening, wrote that it had been laid out under the advice of Old Tom. The Great North of Scotland Railway Company developed Cruden Bay as a major golfing destination, spending £50,000 on the links, a hotel, and an electric tramway connecting the hotel and station. With that kind of an investment having a big name attached to the project would be well advised, and certainly Old Tom’s name brought a cache Simpson’s could not. It is also entirely possible Morris did give some limited advise at some point, nonetheless it seems clear based on the preponderance of reports the original design was Simpson’s. In 1902 Golf Illustrated wrote, “Since its inception three years ago, Cruden Bay has rapidly asserted itself as one of the finest greens in the kingdom. On the occasion of the inaugural tournament, the professional competitors were loud in its praises, and Archie Simpson, of Aberdeen, was congratulated on what is undoubtedly his masterpiece.”

In 1903 Simpson was back at Stonehaven for a redesign. In 1905 it appears he laid out Banchory, and the new course at Balgagask. In 1909 he collaborated with S.Mure Fergusson on the design of Duff House, constructed by Andrew Simpson his nephew and the pro at Cruden Bay. In 1909 he designed Murcar. Murcar originally was to be a joint effort with Harry Vardon but for whatever reason Vardon opted out. There have also been claims Archie designed Nairn in 1887 but I have yet to find any credible evidence. Presently the official position of the club is Archie Simpson of Royal Aberdeen laid out the course in 1887, although on occasion they substitute Andrew Simpson’s name. Royal Aberdeen was not founded until 1888, and Archie was not its pro until 1894, and Andrew Simpson was 13 years old in 1887. The evidence points to Tom Morris as Nairn’s original designer, so if Archie was involved it was likely some time after 1887.

In 1911 Archie Simpson immigrated to America accepting a position as professional of the CC of Detroit. Its not known why he moved to the States but there are several possibilities. Financial considerations could have certainly been one – following the success of his brother-in-law and a number of other Carnoustie men in America. Another possibility was his relationship with Carter’s Seed Company. Carter’s was heavily involved in golf course construction. Murcar had been one of their projects, as was the new course at Detroit, designed by HS Colt. When Simpson arrived in the States his first responsibility was to oversee construction in conjunction with Carters’ foreman Leonard Macomber.*

After a decade at Detroit Archie Simpson returned to Carnoustie in 1921 and stayed for a year. His wife and children came over before him, as did George Low’s wife. Apparently there was a family issue or illness. Late in 1922 Simpson returned to America to oversee the construction of Vincennes CC in Indiana, designed by William Langford. He remained there as pro for a couple of years and then moved to Tam O’Shanter in Detroit, designed by CH Alison and finally Clovernook in Cincinnati, again by Langford. Its not known if he was involved in the construction of those last two courses. He eventually retired to Detroit where he died in 1955, age 88.

* The American arm of Carter’s was Patterson, Wylde & Co. based in Boston

Charles Gibson “ Born in 1860 at Musselburgh Charles Gibson was the son of a tavern-keeper with no direct connection to golf. Growing up in the Mill Hill section of Musselburgh it was impossible for Gibson not be exposed to the game, and eventually, like many other Musselburghers, he found himself employed in its bustling club-making industry. Initially Gibson apprenticed under Old Willie Dunn but in 1882 he moved to North Berwick to work with Willie’s son Tom. Tom Dunn was keeper of the green at North Berwick and a club-maker. While at North Berwick Gibson met Helen Ramage, and they married in 1883. In 1886 Old Willie Dunn’s other son Willie Jr. became the professional at Royal North Devon, and the next year Gibson joined him as a club-maker. When Dunn left for Biarritz in 1888 Gibson was appointed professional.

Charles Gibson

Charles Gibson was not an accomplished golfer â€he competed in a few Opens but never finished in contention. Reportedly he didn’t play much golf and had little interest in teaching the game. His fame and prestige came as a master club-maker. Some considered him the premier craftsmen of his era, known for his hand-made work. In 1924 he was given the Royal patronage after making a miniature set of golf clubs for Queen Mary’s dollhouse at Windsor Castle. His standing as a club-maker was demonstrated at the 1911 Golf Exhibition, where he was chosen senior judge with Willie Park, Jr. and Willie Fernie his assistants.

When the game’s popularity took off in the 1890s Gibson was uniquely qualified to provide both golf clubs and golf courses. A quick glance at his list of designs shows he rarely went outside Devon, Cornwall, Somerset and South Wales. Gibson designed the nine-hole golf courses at Sidmouth and Lelant (West Cornwall) in 1889. He added the second nine at Lelant in 1894. In 1890 he designed the first nine at Burnham & Berrow, and extended it to 18 in 1896. In 1892 he laid out the first nine at Porthcawl, and designed nearby Ashburnham in 1894. This was followed by South Devon (1895), Wollacombe (1895), Churston (1896) and Thurlestone (1897).

Without doubt Gibson was the premier man in that part of England, and the totality of his involvement is likely understated. There are several courses in that neighborhood, formed in the 1890s, with uncertain antecedents – among this group are Tenby, Pennard, Newquay, and St. Enodoc. Gibson is the logical candidate, not only because of his preeminence in the region but also because they exhibit his typical quirkiness. One also wonders – based on his long service – what affect he may have had upon Westward Ho!

Gibson continued to design courses after 1900, including Lahinch in 1906 (his one known excursion outside the region) and Tourquay in 1909. At Lahinch he pushed the course closer to the sea and into the dunes. Charles Gibson died in 1932 at Westward Ho! where he had resided as professional for 44 years.

George Lowe – George Lowe was born in 1856 at Carmyllie, Scotland “ just seven miles from Carnoustie. Carmyllie was known for its flagstone exported worldwide for roads and buildings. His father was a stone quarrier in the Carmyllie Quarry. The Lowe family moved to Carnoustie in 1864, and it was there George was indoctrinated to the game, eventually becoming an apprentice to club-maker Frank Bell. He was working for Bell in 1873 when Old Tom Morris extended Carnoustie to eighteen holes. Morris’s version featured 13 hole of between 200 and 300 yards, and according to an article Lowe later authored he was not overly impressed by the results especially the large number of holes he described as Ëœa drive and a kick.’ Ironically he would later collaborate with the Old Tom.

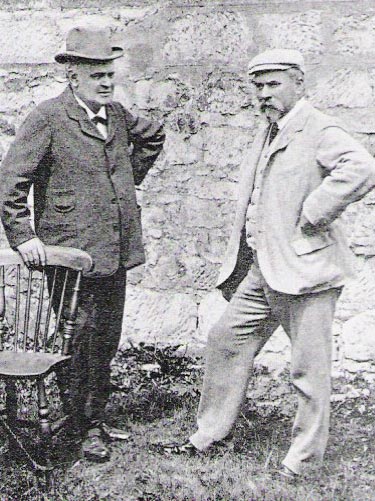

This photo is from the first professional tournament at Lytham in 1890. Back row left to right: George Lowe, Alex Herd, Jack Morris, Willie Campbell, and Hugh Kirkaldy and front row left to right: Willie Park-Jr., Andrew Kirkaldy, Tom Morris, Willie Fernie, and Archie Simpson.

After a short stint working at Leven Lowe took a position assisting Jack Morris at Hoylake in 1877. He remained at Hoylake for a decade, and although his primary responsibility was clubmaking he must have observed Morris’s renovation of the links, and perhaps even assisted. While at Hoylake he married Annie Allen, an Irish girl working as a cook for a local family. The Lowes would eventually produce six children.

Lowe was a good golfer but never a great one; his best finish in the Open Championship was sixth. He was however an accomplished teacher and club-maker. AJ Balfour reportedly used a set of Lowe’s clubs. Lowe claimed he was the first to introduce the golf bag while at Carnoustie.

In 1887 Lowe designed and built Lytham & St.Annes, and then became its custodian. It was during the Lytham years that Lowe began laying out golf courses, and like many successful golf architects of that period his influence was regional, working mostly in Lancashire, Chesire, Yorkshire and the Isle of Man. In all he claimed to have designed and redesigned 100 golf courses. The most prominent among them were (Royal) Lytham & St. Annes, (Royal) Birkdale, the second nine at Seascale, and St. Annes Old Links. This is a list of his known designs:

1887: Lytham & St.Annes, Hesketh

1888: Rochdale

1889: Wilmslow, Birkdale

1891: Pleasington Lodge, Knutson, Maccelsfield, Windemere, Penrith, Studley Royal

1892: Preston

1893: Anson

1894: Worsley, Walney Island, Howstrake (w/Tom Morris), Burnley

1895: Halifax, Rowany, Horwich, Preston (new course)

1896: Hallowes

1897: Seascale, Lytham & St.Annes (new course)

1901: St. Annes Old Links, Colne

1902: Nelson, Didsbury, Wigam

1904: Blackpool North Shore, Saddleworth

1905: Lancaster, Morecambe

1909: Knutson (redesign)

1911: Peel (redesign)

In 1905 Lowe left Lytham-St.Annes and set up shop at St.Annes Old Links. Six years later he left that club and opened a storefront in the city of St.Annes. His wife Annie died in 1919, and the following year he moved to Australia with his daughter Annie, joining four sons already living down under. He settled in Queenscliff, Victoria, close to Barwon Heads GC where his son George was the professional. He remarried, took up vegetable gardening and dabbled in design, advising Queenscliff GC on their bunkering. George Lowe died in Australia in 1934.

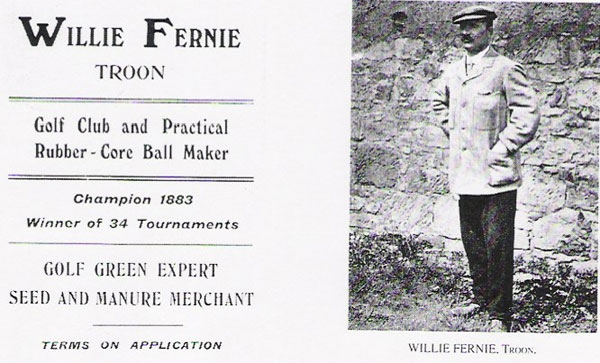

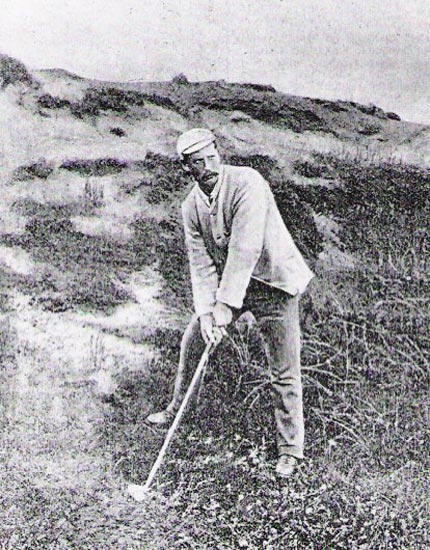

Willie Fernie “ Born in 1858 at St. Andrews Willie Fernie was the son of a caddie. One of five golfing brothers, he won his first professional competition at age 15. In the 1882 Open Championship he finished second to Bob Ferguson. The following year he finished in a tie with Ferguson at Musselburgh, eventually winning a play-off by a stroke and preventing Ferguson from equaling Tommy Morris’s record of four consecutive championships. This was his only Championship though he did finish second five times. Fernie was known for his graceful and easy swing, and was in great demand as a teacher. He gave a series of successful lectures in London and elsewhere on the ËœPerfect Swing’ “ thought to be the first example of indoor instruction.

Willie Fernie

Fernie’s first job was at Dumfries in 1880 as greenkeeper. In 1884 he took the professional position at Felixstowe Ferry, and immediately redesigned its nine-hole course. Bernard Darwin played his earliest golf at Felixstowe and idolized Willie. “By the tee, and close to Martello tower, stood the professional’s little shop, with its beautiful smell of pitch. Out of it would come Willie Fernie, an heroic figure in short sleeves, an apron, and sort of yachting cap with a shining peak, waggling a newly-made club in his vigorous wrists.” Darwin told the story of nearly being killed by a half-topped hook off the club of Fernie while exiting a boarded-bunker known as Morley’s Grave, “that,” he said “would have been a glorious death.”

From Felixstowe Fernie moved to Troon, replacing George Strath in 1887. He would remain at that club for 37 years, retiring in 1924. It was during those Troon years that Fernie became one of the most sought after and active designers of his era.

A partial list of Willie Fernie’s designs and redesigns: Aldebrugh, Outney Common, Berwick-upon-Tweed (Goswick), Skinburness, Wemyss Bay, Lamlash, Abington, Anstruther, Thronhill, Shandon Hydropathic, Landside, Troon Portland, Shiskine (Blackwaterfoot), Douglas Park, Strathaven, Dunaghadee, Chateau Royal d’Ardenne (Belgium), Turnberry-Old, Turnberry-New, Seacroft (Skegness), Strathkendrick, Appelby, Caldwell House, Gairloch, Troon Municipal, Golf du Touquet (France), Maybole, Colwell, Usk, Whitsand Bay, Cardross, Bathgate, Pitlochry and Callander.

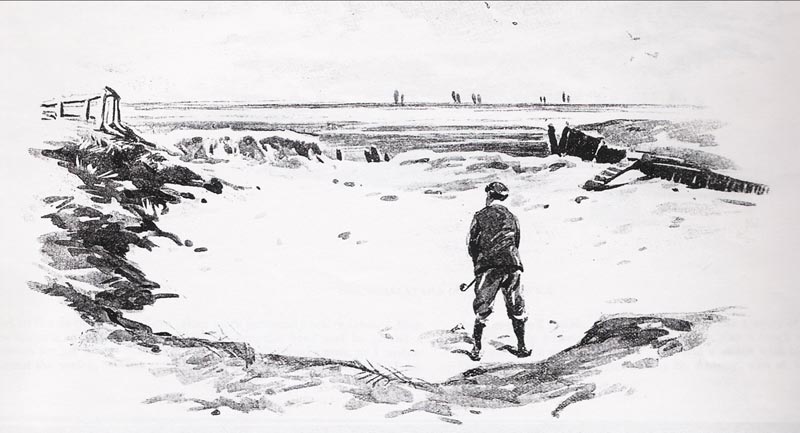

Certainly an impressive collection but his most acclaimed project has to be Royal Troon. Originally laid out by Strath, Fernie transformed Troon over his long tenure – among his additions was the world famous Postage Stamp.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Fernie was not a regional designer; his scope was more expansive, not only throughout the UK but also on the Continent. Fernie also created important designs before and after 1900, for that reason is considered a transitional architect. Willie Fernie died in a nursing home at Glasgow in 1924 just months after his retirement.

Willie Campbell “ Born in 1862, Willie Campbell like his father before him was a caddie at the nine-hole links at Musselburgh. He learned the game from the great Bob Ferguson, who in the early eighties was the premier player in the world, having won the Open Championship in 1880, 1881, and 1882. In those days nearly all the caddies were professional players, and Willie was no different, competing for money at an early age. Among his contemporaries at Musselburgh were David Brown, Peter Paxton, and Willie Park-Jr.

Willie Campbell

Campbell was a tall strapping man with a demeanor admirably adapted to the difficulties of a match â€fearless and courageous. Willie was regarded as one of the finest match players of his time. Garden Smith of Golf Illustrated described him as a golfing genius. During the 1880s Campbell never backed down from a match â€anywhere, anytime, with anyone. In 1882 an admirer offered to back him, and the following year Campbell issued a challenge to the world. From 1883 to 1890 he played every player who would meet him for money. Some reports claim he never lost a match during those years, although I have been unable to substantiate that claim. What is certain Campbell delivered some incredible beatings to the world’s best players.

Despite all his success his most famous golfing moment was a failure. In the 1887 Open Championship at Prestwick, where Campbell was an assistant professional, Willie was coming home the sure winner when he healed his drive at the 16th and found a deep bunker (later dubbed Campbell’s grave). The gallery tried to convince him to play backward, unfortunately he ignored their advice and took eight instead of four. Willie Park-Jr won the title by a stroke. Horace Hutchinson told the sad story of coming into Charlie Hunter’s shop after Willie had thrown away the Championship. On either side of the shop were upturned buckets “ on one sat Willie Campbell and on the other his caddie, both weeping bitterly.

After the disappointment Campbell challenged the champion to a match over 72 holes. He defeated Park 18 up with 17 to play. The year before he had finished second in the Open to Davie Brown at Musselburgh. Again he issued a challenge; ultimately defeating Brown 13 and 12. He had similar one-sided victories over Bob Martin and Willie Fernie. His match against Archie Simpson may have been the most publicized, it was held over Carnoustie, St.Andrews, Prestick and Musselburgh in front huge crowds. The battle ended at Musselburgh with Willie up 16.

Campbell was engaged as professional at Prestwick (1887-88), Ranfurly Castle (1889-91) and North Berwick (1892-94). His first architectural involvement appears to be at Ranfurly Castle in 1889, where he designed their nine-hole course. In 1891 he laid out the wild links at Machirie on Islay, considered a cult classic today. That same year he designed Cowal, Rothesay and Kilmacolm in western Scotland, and in 1893 the first nine at Seascale.

Campbell suffered from a rheumatic condition and immigrated to America in 1894 – setting up shop in Boston. 1894 was a critical year for golf in Boston, and the United States. There were four major projects that year “ the expansion of Brookline, the laying out of the first nines at Essex County, Quincy (Wollaston) and Myopia Hunt. Campbell was responsible for all four. Considering the importance of those courses, particularly Brookline and Myopia, its surprising he hasn’t received more recognition.

Over the next few years Willie continued to lay out courses throughout the region including Oakley, Wannamoisett (RI), Winchester, Worcester, New Bedford, Beaver Meadow (NH) and Franklin Park. Although not as prolific as some he was without doubt one of the most important early golf architects, especially in America. Unfortunately his place in American golf architecture history has been largely ignored. Willie Campbell’s life was cut short when he succumbed to cancer in 1900. He was only 38 years old.

Willie Park-Jr. “ The son of Old Willie Park, Willie Park-Jr. was born in 1864 at Musselburgh. ËœAuld Wullie’ was a rival of Old Tom Morris, and one of the greatest golfers of his day. The elder Park won the first Open Championship in 1860, and then again in 1863, 1866 and 1875. Mungo Park, Old Willie’s brother, won the belt in 1874. Young Willie followed in their footsteps and began competing at an early age.

Willie Park Jr.

In 1880, at the age of 16, Willie Park-Jr. was appointed greenkeeper and professional at the Ryton Golf Club in northeast England, his uncle Mungo was the pro at nearby Alnmouth. Willie later admitted he spent as much time at Alnmouth as he did at Ryton. One gets the impression he leaned heavily upon his uncle. Willie returned in Musselburgh in 1884 to assist in his father’s club-making business. Old Willie’s health was on the decline.

Willie Park-Jr. won his first Open Championship in 1887 at Prestwick and repeated the feat in 1889 at Musselburgh. Like his father before him he never refused a big money match. In 1888 he issued his famous £100 challenge to the world, and over the next decade met every great player of his era with mixed results although on balance he won more than he lost. As a golfer Park was known for two main attributes: a very cool demeanor and a wonderful putting stroke. Even in adversity he always kept the same placid exterior. Horace Hutchinson suggested he would have been better served letting off a little steam now and again, especially in the heat of a match. Ironically the man best known for high stakes matches was considered more dangerous in medal play.

On the business side Park established a successful golf equipment operation with shops in London, Edinburgh, and Manchester in addition to the original Musselburgh shop. In 1895 he made a tour of America, playing in number of arranged matches although his primary objective was to promote his business and open a shop in New York (which he did although it ultimately failed due to heavy tariffs). On this visit he agreed to become the professional at Shinnecock Hills, commencing in the spring of 1896. The following year his return was delayed so Shinnecock was forced to go another direction. One has to wonder how history would have been altered had he taken the position.

Near the end of the 1890s Park was so busy with business he had little time for playing the game. Despite his inactivity he nearly won his third Open Championship in 1898. Willie played brilliantly and led throughout but missed a three-foot putt on the final green to tie Harry Vardon. Following a heated debate over who was the better player the famous Vardon-Park challenge match was arranged – thirty-six holes at Ganton and thirty-six holes at North Berwick. It was dubbed the match of the century and drew enormous interest â€10,000 spectators were on hand at North Berwick, thought to be the largest golf gallery to that point. In the end Vardon won 11 and 10 but the loss did nothing to diminish Willie’s reputation, if anything it was enhanced.

Park’s first design effort came at Innerleithen in 1886, where he was sent as a substitute for his father, but his architectural career didn’t start in earnest until the boom of the 90s. There has been an assertion that father and son collaborated during these years but I’ve yet to find evidence the two ever worked together. In fact Old Willie was more or less inactive after 1886 due to failing health. He passed away in 1902.

Willie Park-Jr. is recognized today as one of the great golf architects in history, however that reputation was not made based on his work in the 1890s. The following is a chronological list of courses Willie Park designed or redesigned in the nineties:

1892: Bathgate, Bo’ness, Jedburgh

1893: Baberton

1894: Bridge of Weir, Muswell Hill, Glencorse

1895: Torwoodee, Misquamicut (USA), Shelburne Farms (USA)

1896: Dalkeith, Wembley, Lauder

1897: Dieppe, Dunnington, Turnhouse

1898: Gullane #2, Bruntsfield

1899: St. Boswells, Burntisland, Sunningdale

Make note there are two high-profile courses normally associated with Park missing from the list – Silloth and Western Gailles. Silloth-on-Solway was laid out by his friend David Grant and constructed by his uncle Mungo Park. Willie did inspect the course near the end of construction, and was said to be very impressed, but credit should not be assigned based upon an inspection or last minute advice. The confusion surrounding Western Gailes was due to the fact Willie listed Gailes, Ayshire as a golf course he designed, but that course was Glasgow Gailes, designed in 1912. Western Gailes was designed and built in 1897 by the greenkeeper F. Morris. A third course deserves mention as well, that would be Burntisland. The club claims Park designed their new course at Dodhead in 1896. The club did acquire the Dodhead property in 1896 however they were not playing golf at that site until 1899, and it is unclear if Willie is responsible for the 1899 layout or was involved in a later redesign. We do know the greenkeeper John Drurie carried out a number of changes in the early 1900s.

During the nineties to say Willie Park distinguished himself would be a mischaracterization. His golf courses were no better or worse than most of his contemporaries, and he followed many of the common practices of the period “ the cop bunker, the straight out and straight back approach to routing, the crossing hazard often placed at regular intervals and a generally penal approach to hazard placement. Much of this is documented in his 1896 book The Game of Golf in which Willie dedicated a chapter to golf course design. But there were also advancements evident in that book. Park was developing some progressive ideas beyond the old stereotypical ones, for example promoting the use of natural hazards and the importance of variety.

Like most of his fellow architects at that time Park’s success (or lack of success) could easily be predicted. When given good material near the sea he produced good results, when given an ordinary inland site he did nothing of consequence â€that is until 1899. That year he began Sunningdale, and it was a major advancement. It was considered revolutionary for two primary reasons: first its scale was enormous for that time, and secondly the severity of the site, not only topographically but also in the nature of the ground. At that time it was considered unadvisable to make a course over sandy ground overgrown with heather. Sunningdale was the first course to be wholly sown from seed, at a considerable cost I might add.

Soon after being engaged at Sunningdale Willie began Huntercombe, and it was another breakthrough design. Huntercombe was unusual for its use of hazards “ man-made and natural “ strategically placed in central and flanking locations. These two courses were constructed simultaneously, and Willie reportedly made frequent trips back to Musselbourgh seeking inspiration. That was a novel approach as well. Both Sunningdale and Huntercombe opened to positive reviews in 1901, and were tremendous improvements over the dreaded Victorian courses, but one should not get the impression they were polished gems. Golf architecture improved incrementally not overnight.

Willie Park’s history is a microcosm of golf architecture history. Producing inconsistent quality in the ninties followed by very good to excellent work in the decades that followed. After suffering from a Ëœnervous breakdown’ Willie Park died in 1925 at an Edinburgh nursing home.

Other professionals “ There are other professionals from this era who deserve mention. Below you will find a brief profile along with a list of their most prominent designs:

Peter Paxton of Musselburgh was born in 1857. Runner-up in the 1880 Open, Paxon was the professional of several high-profile clubs, including Malvern, Tooting Bec and Hanger Hill. He was also one of the premier club-makers of his time, an art he learned from David Park, Old Willie’s brother. Peter Paxton was a very active designer in the 1890s. His designs include Wimbledon Park, Limpsfield Chart, Rochford Hundred, Romney Sands and East Berkshire.

James McKenna was born in 1874 at Clontarf, just outside Dublin. Very little is known about this Irishman. McKenna seems he have been associated with railroad in his early years, which led to some early designs, including Ballybunion and Lahinch. He was the professional at Lahinch, Carickmines, Portmarnock and Rossmore. His designs include Lahinch (with the help of Alexander Shaw), Ballybunion, Waterville, Hermitage and Killiney.

Jack Morris was born at St. Andrews in 1847, the son of George Morris, brother of Old Tom. George Morris laid out the first nine at Hoylake assisted by Robert Chambers,Jr. Jack Morris became professional at Royal Liverpool in 1869, and remained at the club for sixty years. During his tenure he was responsible for expanding and perfecting that famous golf course. It was his unconventional but charming version of Hoylake, featuring the old Rushes hole, the old Hilbre, and the Dun Bunker, which was beloved by so many old-timers, including Darwin. In addition to Hoylake Morris was quite active laying out courses throughout the region. His designs include Hoylake, Conwy (Caeenarvonshire), Grange Park, Rhyl, and Pwllheli.

Douglas Rolland was born at Earlsferry in 1860. Starting at the age of 13 he worked for several years as a stonemason. Not surprising Rolland was known for his powerful build and prodigious driving. During his prime he was considered the best player never to have won the Open Championship. Although his architectural portfolio is somewhat sparse he was a major influence upon the great HS Colt. Rolland’s designs include Malvern, Hastings-St. Leonard and Rye, the latter two assisted by Colt.

Charles Hunter was born in 1836 at Prestwick. Charlie Hunter was a caddie and a clubmaker under Old Tom Morris, and succeeded him at Prestwick in 1864 where he remained until his death in 1929. Charlie Hunter operated an extensive club-making business from his shop at Prestwick. His designs include Machrihanish, Prestwick St. Nicholas and revising Prestwick.

Charles Hunter and Jack Morris

Jack Rowe was born at Westward Ho! in 1870. He was a protégé of Horace Hutchinson who convinced him to make a career in golf rather than attending Art school. He was the professional at Royal Ashdown Forest for over fifty years. His designs include Lewes, Piltdown, Ifield Lodge (w/Ernest Lehman), Morecambe, Folkstone and Shernfold Park.

Ramsey Hunter was born in 1854 at Edinburgh. He learned the trade of carpentry from his father who was a cabinetmaker. He played his early golf over the historic Bruntsfield Links. In 1888 Hunter was hired as professional/greenkeeper of St. Georges, Sandwich, and did much to improve that course during his stay. In 1900 he was dismissed for being Ëœworse with drink.’ In addition to his work at Sandwich he designed Porthcawl and expanded Deal. Ramsey Hunter died in 1909 while collaborating with Willie Park-Jr at the aptly named Gravesend (Mid-Kent GC).

Conclusion

Now that we have examined this period by way of its leading practitioners there are several observations to be made. The first point relates to the title of this essay, and the number of golf courses erroneously attributed to Old Tom Morris. Old Tom is one of the most important figures in the history of the game, and one of the most significant course designers of this early period. Not only did he lay out a large number of golf courses, he was instrumental in spreading the game at a most crucial time. That being said there are scores of courses (some of them very prominent courses) that Morris biographer Robert Kroeger and others have given to Old Tom that are actually the work of others. In fairness to these Morris biographers it is not entirely their fault. In Old Tom’s day clubs were eager to have his name associated with their golf courses. A site inspection, a grand opening appearance, a minor redesign, advise on greenkeeping matters or the use of the clubhouse restroom might result in Old Tom being given design credit. Lahinch and Rosapenna are two glaring examples. It should also be noted this practice is not unique to OTM – there has been tendency for some clubs to overplay the involvement of James Braid, Donald Ross and other favored architects. Whatever the motivation of these clubs and authors, there is no need to exaggerate Old Tom’s already outstanding record, especially when it is done at the expense of these men.

The second observation involves the influence of St. Andrews and other historic courses. It has often been stated that the Old Course was the primary influence on the development of golf architecture. And while there is some truth to that claim it is interesting to note how many of these early architects came from Edinburgh and were likely influenced by the courses of that metropolis: Bruntsfield, North Berwick and especially Musselburgh. In fact if we were to compare the production of these architects by their native course undoubtedly the by-product of Musselburgh would out number St.Andrews. Perhaps it is time we gave more attention to Musselburgh and its architecture.

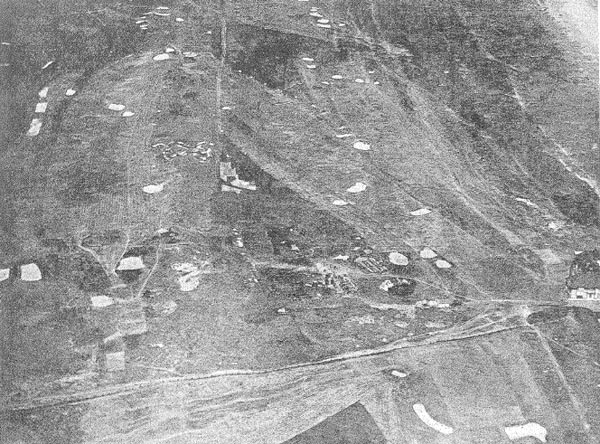

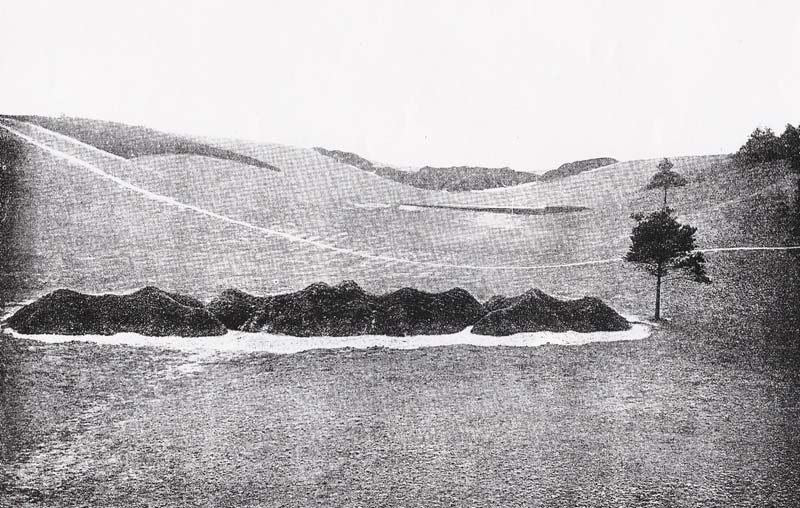

Musselburgh’s impact on golf course architecture is sometimes underestimated. Pictured above is Pandemonium, one of Musselburgh’s famous hazards.

Another observation surrounds the phenomenon of the amateur architect. This was a time when amateurs were making significant contributions throughout society â€in the sciences and in the arts and elsewhere. The factors contributing to amateurism included superior education, the unprecedented dissemination of information (through books, magazines, newspapers, libraries, museums, etc,) and increased leisure, allowing time to follow other pursuits. John Ruskin, Robert Chambers, Nathaniel Lloyd, and Gertrude Jekyll are individuals who made major contributions in fields outside their formal training. Based on the societal trend it is no surprise golf produced its own group of amateur architects. It should also be noted that professionals, or more seasoned amateurs, often assisted these amateur architects. There has been a tendency to ignore that fact and give these amateurs a mythical persona. I hope we have avoided this pitfall.