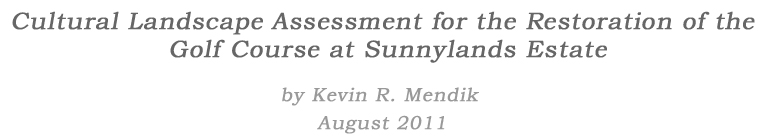

The Context: A private nine-hole golf course sited within the 200-acre Historic Core of The Sunnylands Estate in Palm Springs, California. Course architects Dick Wilson & Joe Lee. Originally opened in 1965. Historic Restoration and Renovation undertaken during 2010 and 2011.

History of Golf and Golf Architecture in America1

Popular throughout the United States, golf originated in Scotland before the 15th2 Century where it was played on undulating, sandy, seaside terrain known as links. Links tended to be the area between the high tide line and where land became arable; essentially links were the least valuable land and could only be used for grazing. These lands were also in the public domain, and would constitute a Historic Vernacular Landscape.3 Links courses first developed on narrow strips of land and tended to follow an out and back routing: the front nine would extend in a string away from the clubhouse or starting location and the back nine would return along a roughly parallel string. The onset of “golf architecture” began around 1837 when Sir Andrew Playfair, Provost of St. Andrews, directed clubmaker and professional golfer Allan Robertson to upgrade The Old Course, already 300 years old, which had simply evolved from the natural terrain. The two earliest American golf clubs,4 the South Carolina Golf Club and the Savannah Golf Club, were founded in 1786 and 1795 respectively, but had gone out of existence by 1811.5 The golf course known as Oakhurst Links in White Sulfer Springs, WV was founded in 1884, but also closed from 1910 until its restoration in 1994. The oldest continuously operating golf club in the U.S. is Foxburg Country Club, near Pittsburgh, founded in 1887.6 Less than 50 courses existed in America at the time of the U.S.G.A.’s founding7 in 1894, but by 1900 there were over 1000 although all but a handful were primitive by today’s standards. Evolving designs reflected changes in the knowledge base of course designers as more immigrated from the UK, advances in construction technology, and advances in maintenance equipment and mowing practices, along with developments in the science of agronomy.

Natural or Pasture Golf (1786-1900)

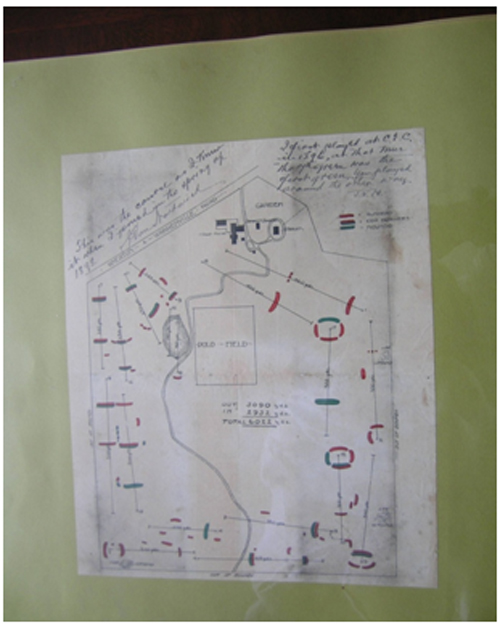

Courses tended to exhibit less formal design intervention and instead tended to be laid out on extant terrain with pre-existing hazards incorporated, including stone walls, roads, and watercourses. Courses often moved from year to year depending upon whose land was available, playing over grazing lands and estate lawns. Greens were often made of sand and doubled as teeing grounds. A handful of courses involved design modifications such as sodded greens located on hillsides or with undulating lateral and greenside bunkers, but these were the exceptions. Livestock were the primary means of trimming grass. Hazards were often modeled after or incorporated elements of the Steeplechase. Riding over stone walls and mounds, across water and sandy areas morphed into the scale appropriate for a golfer to play out of versus what a horse and rider had to cross. The earliest plans were relatively simple and crude by today’s standards.

Above, one of the first plans that incorporated color, although only for the bunkers. Chicago Golf Club, circa 1898. Note that the greens are not delineated except where surrounded by collar bunkering.

The Landmark Period (1900 – 1918)

This era was preceded by the arrival of Scottish pros and designers in the United States in the late 1880s and 1890s, the availability of horse-drawn reel type mowers circa 1895, and the 1899 introduction of the Haskell ball, which flew much farther than the prior gutta percha,8 rendering most existing courses obsolete. These innovations, along with earth-working, allowed course designs to lengthen considerably, and encouraged and allowed designers to incorporate larger lateral as well as cross hazards. The term golf architect was coined by Charles Blair Macdonald, circa 1907 during the design process for National Golf Links of America, located in New York adjacent to Shinnecock Hills.

Macdonald designed and laid out holes replicating the terrain of traditional Scottish links courses, often so precise as to recreate specific holes from various courses. In other cases, he altered or combined elements, and created new holes.

The Golden Age of American Golf Architecture: (1918-1945)

Significant advances in turf grass science and management, such as irrigation systems and more precise mowers, allowed for relatively manicured conditions, resulting in considerably increased green speeds, which in turn meant that elevation changes and slopes on greens had to be less severe that had previously been designed for.9 A combination of post-war prosperity, large tracts of available land near population centers, plenty of available labor, an influx of golf architects, and a surge in interest in the game led to an average of 500 new courses opening each year during much of the mid to late 1920s. These courses departed from layouts emphasizing the center shot, returning to links inspired designs in which each hole could be played a variety of ways, depending upon the golfer’s skill. The use of dynamite, along with more advanced heavy equipment, allowed for course designers to work in, around and through rocky and wooded terrain, a significant departure from the earlier periods.

The Modern Era: (1945- present)10

Beginning in the middle of the 20th century, many miles of paved roadways and the interstate highway system heralded a new era of golf course expansion. Significant changes to the natural land forms became common as large-scale hydraulic earth moving equipment and considerable refinement in the use of explosives became available to the civilian population post-World War II. By the mid 1950s, the widespread use of golf carts was in place, 11 permitting individual holes to be built out of sight of others as the tee of the following hole no longer needed to be close to the previous green. This also freed designers to incorporate significant elevation changes in their courses. The need for cart paths close to an often around tees and greens, along fairways and from greens to the next tee, resulted in a whole new set of factors that golf architects had to factor into each hole. Far more people could play golf into their later years, resulting in a proliferation of courses in the warmer locations (especially Florida and the South West) where retirees were flocking. In addition, new composite metals allowed for lighter clubs, which hit higher and farther and heralded in the era of target golf.

The Course at Sunnylands as a Historic Designed Landscape

Ambassador and Mrs. Annenberg’s private 9-hole golf course at their Sunnylands Estate in Palm Springs, California was designed by golf architect Dick Wilson and opened for play in 1965, placing the course in the category of Modern American golf courses. It was designed in a desert environment with elements of parkland style, such as the incorporation of trees and other plantings, as well as lakes and watercourses. Cart paths were not included in the original design, but 200 yards worth were incorporated on the east side between 1969-1974 and on the west side in 1977. The course was sited roughly on the western half of the Historic Core of the 200 acre estate. Additional improvements to that core included the main residence, various cottages and the guesthouse, the caretaker’s house, three greenhouses, the gatehouse, ancillary working structures, a swimming pool, ponds and landscaped parkland. The course was designed as a nine-hole course at 3385 yards.

The fact that the golf course at Sunnylands is the largest physical feature on the estate indicates the relative importance placed on golf by Ambassador Annenberg. The course was intended for his private use and that of his close friends, family and visiting dignitaries, who in many cases, included sitting and former U.S. Presidents and top professional golfers.12 The extent to which the Sunnylands Trust wishes to interpret the historical context and significance of presidential golf is undetermined, but should be accorded at least some degree of focus, given the history of golfing presidents.

Prior to the decision to restore the golf course and renovate some elements with modern systems, it was necessary to decide the critical Period of Significance13 for which the golf course was to be interpreted and restored to, and the desired future conditions under which it would then be managed, as well as the extent to which various stories and people associated with the golf course would be interpreted. The Sunnylands Transition Project (STP) adopted a position to “do no harm,” which translated essentially into restoring, as closely as possible, the course that DW envisioned and the design elements contained therein, in order to accurately convey his design philosophy and intent at Sunnylands.

Top left, President Reagan. Top right, Lee Trevino and Reagan’s Secretary of State George Shultz. Bottom, President Reagan, Ambassador Annenberg and Tom Watson. Photos copyright the Annenberg Foundation Trust at Sunnylands.

By its very nature as the private golf course of a U.S. Ambassador, frequented numerous times by sitting and former U.S. presidents, dignitaries and public figures, and designed by one of the two most highly regarded golf architects working in the U.S. at that time, the golf course at Sunnylands constitutes a historic golfscape, and would likely qualify for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places, if that designation were to be applied for. The term golfscape is often used to further define historic designed landscapes that have a golf focus or component.14 A Google search of “National Register of Historic Places Golfscape” turns up numerous references to the term being used in association with NR listings and applications. The term has been utilized from types of paintings to golf related destinations.15

The golf course could be argued as having achieved significance upon its opening, based on its having been designed by a” master” golf architect as defined by the NRHP criteria.

Available information16 for the project included aerial photographs from August of 196517 and 197418 , original plans and drawings, an analysis of subsurface conditions, on course interviews and discussions with Robert von Hagge, (a former associate of DW) and Tony Cuellar, the original course superintendent who had been on site from December of 1964, following the completion of the majority of the construction work .19 Based on the sum of that information, it was possible to determine how much of the historic integrity of the course remained including the original sizes and shapes of greens, tees and bunkers, the size and shape of the water bodies, and their intended relationship with the greens and fairways as envisioned by DW.

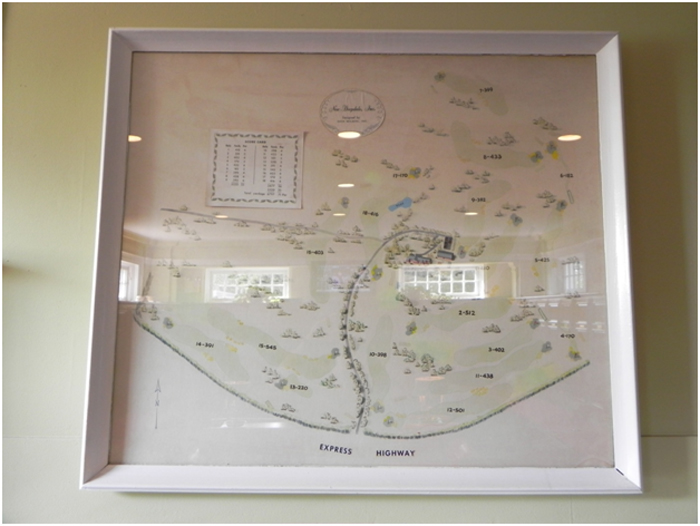

Equally important was the ability to identify what changes had occurred to the golf course, both active (intentional changes such as the addition of tees) and passive (changes to mowing and maintenance patterns resulting in reduction of green sizes, alterations to bunker shapes, along with reduction in bunker depth from added sand over time). The restoration included a renovation component which added and in some cases, relocated various post-Wilson alternative tees, to allow for an 18-hole course that could accommodate as many as three distinct holes for single green locations, and allow for a Historical, Championship or Tournament experience. In addition, as shown in the Jackson Kahn plan below, a driving range and practice chipping and putting green were added to the Northeast of the house.

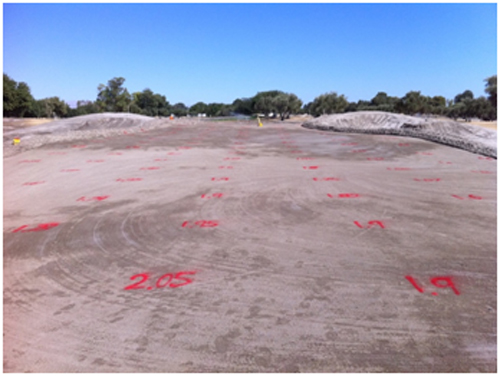

#6 green with grid markings, May 2011. David Kahn photo, Copyright The Annenberg Estate At Sunnylands.

Most renovations at modern and many classic era golf courses have been designed to accommodate the longer drives and higher trajectory approaches to greens than were possible in the early 1960’s. This is most evident when at renovations where tournament level play is anticipated. This is the case at Doral’s Blue Monster, Royal Montreal’s Blue Course and Cog Hill #4, several of Wilson’s best known designs which host professional level tournaments. Those courses today are more likely associated with Rees Jones, the renovation architect at each course.

However, the approach at Sunnylands was more of a pure restoration; the general distance from tees to hazards was retained at roughly 230 yards, the average driving distance at the time the course was designed. This element not only ensured the integrity of Wilson’s original design, but also the historic integrity of the golf course and by association, Sunnylands as a whole. Therefore, the STP may want to consider offering the use of period golf clubs (steel shafted bladed irons and persimmon headed woods) to provide an experience similar to that which Dick Wilson envisioned when the course was designed. He played with 1960’s era clubs and as with most golf architects, did not design his courses to accommodate the 50-100 plus yard difference that many of today’s golfers can achieve with modern equipment.

Given that restoration and renovation efforts at Sunnylands extend to other features, the addition of new structures and modern systems, such as solar power, and the allowance of public visitation (although not necessarily to the golf course), the golf course will continue to be consistent in terms of size and location relative to the larger landscape much as it did when it was first constructed. The degree to which the course retains its exclusivity and access is undetermined. At the time of its construction, the course was considered state of the art, not only for nine-hole courses, but for golf courses in general and was designed by one of the top golf architects then working in the field. It is still among the most highly ranked nine-hole courses in the country.20 Therefore, restoring the course to the conditions that were envisioned by the original architect serves to strengthen the overall historic fabric of the Sunnylands Estate. Wilson did not believe in ladies or forward tees, however, shortly after his departure from the project, additional sets of tees were added. On Mrs. Annenberg’s request, Lee added additional tee boxes in the 1980’s, resulting in a course that could play to 18 holes of varying distances.

The Nine Hole Course

Although 18-hole courses are considered the standard for today’s tournament play, it was far more common for early American courses to be nine holes (or six, three, twelve or whatever the property allowed for).21 None of the five clubs who came together to found U.S.G.A. clubs began as 18-hole layouts. The first 18-hole course in the U.S. didn’t even appear until 1895 at the Chicago Golf Club. The first U.S. Amateur and first two U.S. Open Championships were held at nine-hole courses, The Newport Country Club and Shinnecock Hills respectively. Foxburg, Oakhurst Links and many of the earliest clubs have remained at nine holes. Entire books have been devoted to nine holes courses.22 Virtually all the great Classic Era golf architects have several nine hole designs to their credit, often among their earliest work. In many cases, 18-hole courses from that era are essentially two distinct nine-hole courses often designed and built by different architects anywhere from a few years to a few decades apart. It is not uncommon for Classic or earlier nine hole courses to have added another nine, and/or reworked their old nine into an 18-hole layout during the Modern era. This is not an American phenomenon; the same development pathway of golf courses in other countries rings largely true, with the exception being modern resort style courses. The Links at Musselbrough (below), arguably Scotland’s oldest continuously operating course dating to 1744, is a nine-holer that was later surrounded by a racetrack across which two of the holes play today.

Several early American courses played across horse race and bicycle track ovals, among them The Country Club and the course at Vesper, both in Massachusetts. While it is a matter of opinion that few truly great nine-hole courses have been built during the Modern era,23 they continue to be an integral and important part of the game.24 However, since the beginning of the Modern era, far fewer nine-hole courses have been developed than in earlier periods. Roughly 28% of golf courses in the U.S. today are 9-holes. According to the National Golf Foundation, that percentage has dropped from 44% in 1995. From 1995 to 2010, over 1,000 9-holers courses have either been turned into18 holes or have gone out of existence. A larger portion of the Top 100 Classic (GolfWeek) Courses began as nine than their counterparts in the Modern list. Fortunately for golf purists who enjoy the old style courses, many unheralded and out of the way nine-holers, remain largely untouched. This is due in some cases because the 9 hole courses tended to have fewer resources and many didn’t put money into large scale and costly renovations or expansions. However, Golf Digest’s Top 100 Courses list has not contained a nine-hole course since 1968.25

Private Estate Nine-Hole Courses

Unlike in Scotland where golf originated on common land, many of the earliest golf courses were laid out on private estates. Although golf was sometimes tolerated on town commons in the U.S. there were no public courses until Van Cortlandt Park opened in New York in 1895.

Individuals with names such Rockefeller, du Pont, Mellon, Vanderbuilt and Edward Harkness (financier to J.D. Rockefeller) had private courses built for them on their east coast estates.26 On the west coast, Charlie Chaplin and comedian Harold Lloyd had nine-hole par three courses built on their Hollywood lawns. In each case, these individuals employed the top talent of their era, including C.B. Macdonald, Donald Ross, Seth Raynor27, Wayne Stiles, Walter Travis, A.W. Tillinghast, Dr. Alister Mackenzie and William Flynn who worked for the Rockefellers re-designing their course at Pocantico Hills in Tarrytown, NY in the 1930s.28 In Chicago in 1926, Albert Lasker, who had made his fortune in advertising, hired Flynn to design and build his own private course. Lasker was Jewish and had been blackballed from Chicago’s established private clubs. Similar experiences may have led other prominent individuals to build private courses, but for many, as with Ambassador Annenberg, they simply wanted privacy and the enjoyment of knowing they would always be first off the tee and not have to leave home to play golf.29

It is hardly surprising then that Ambassador Annenberg, an intensely private individual with considerable resources would desire to have his own golf course built. He no doubt could have afforded his own 18-hole course, but it may simply have been that 9 holes were all that was desired within what was envisioned for the property. He spent considerable time playing golf at the Tamarisk CC, located just to the west of Sunnylands, which offered views similar to those that were taken advantage of for his personal course.30

His choice to retain Dick Wilson and Joe Lee31 was logical, given that Wilson was among the most highly regarded golf architects in the country at the time. They were in the process of completing the 18-hole course at La Costa in nearby Carlsbad which opened the year before Sunnylands. Wilson and Lee had done work for the Bel Air Country Club in 1961, and were already well regarding in California. Their work at Bel Air included elevating and substantially expanding several of the greens, putting in new fairway contours and adding and renovating numerous bunkers. 33 Wilson also had experience with original desert designs, including Moon Valley CC in Arizona in 1958, and had worked in Texas and Australia. His credits by then also included several 9-hole projects as well as the highly regarded Palm Beach Par Three GC which opened in 1961. While working on Sunnylands, they were also designing Desert Rose GC in Nevada, which opened in 1964.

Considerable private estate course development continued into the Modern Era, not only in California, but on the eastern United States as well. In the early 1960s, Larry Wien, the part owner of the Empire State Building, commissioned his own 18-hole course to be built in rolling and rocky terrain in Easton, Connecticut. The site was almost the exact opposite of the terrain around Palm Springs, and required considerable blasting to accomplish, but as with Sunnylands, cost was not a limiting factor.

Mr. Wien hired Geoffrey Cornish to design what was then known as The Golf Club At Aspetuck. As with Sunnylands, it was completed in 1965, and for many years was Mr. Wien’s personal course. Gradually he began inviting paid corporate memberships, largely from the New York real estate, banking and finance community, and he eventually offered traditional individual memberships in the early 1970s. It is known today as the Connecticut Golf Club.34 Private estate courses continue to be built in varying configurations. Some are 18 holes, some are 9 and others are some combination.35 Some remain strictly private, while others are opened regularly or occasionally for charitable or other functions.

As with any desert course of the modern era, irrigation and drainage had to be incorporated at Sunnylands and fully functional at all times. Various types of plantings, from naturally indigenous vegetation to imported plantings were regularly included and continue to be so used today. Because Sunnylands was a private course, either as much or as little land could have been utilized for the holes, with options to space then close together or allow broad areas between holes. A decision was made to orient the golf holes together primarily on the western portion of the property, instead of having them wind throughout the 200 acres.

The Golf Architect Dick Wilson

When Dick Wilson passed away in 1965, he was among the preeminent American golf architects of the 1950s and 1960s.36 He did work at some of the country’s most renowned venues, including the 18th hole at Seminole Golf Club in Florida and three holes at Winged Foot’s West Course in 1959.37 However, due to his reputation as being gruff with his clients and his use of alcohol, especially in the last few years of his life after the passing of his wife, his reputation as a golf architect has been diminished and somewhat overlooked.38 He has been described as “warm, direct, rugged, extremely likeable” and at times, was considered “temperamentally volatile.”39 Other descriptions of him include being a “gruff, surly, unpolished artist-in-the-rough [although] his basic warmth and humor still manage[d] to show through.”40 He was known to alienate both business associates and in some cases, his clients, including Ambassador Annenberg.41 His actions got him removed from a number of projects which were then completed by his associates.42 Former associate Robert von Hagge described him as a “ball of barbed wire and ground glass. But when the situation calls for compassion he will melt like a marsh-mallow. He’s such a bug on honesty that he does all his business with a handshake.”43 von Hagge also noted that Wilson had been drinking by the time he began working for Wilson in 1955, and noted that it picked up by 1958. While building Cog Hill #4 in Illinois, he was not allowed into the clubhouse in order to keep him away from alcohol. According to Wilson, “That’s the damn most exclusive club I’ve ever seen in my life; they won’t ever let me in the clubhouse.”44

During the last several years, restoration and renovation work on a number of his golf courses have led to a resurgence of interest Mr. Wilson.45 Among them are Cog Hill #4 (Dubsdread) in Lemont, Illinois, a public course which was renovated during 2008 by Rees Jones (son of Robert Trent Jones).46 The course has been a constant PGA Tour venue since the Western Open from 1991-2006, and currently hosts the BMW Championship,47 the third stop on the season ending FedEx Cup series. Four U.S.G.A. Championships, most recently the 97th U.S. Amateur in 1997 have been contested at Dubsdread. The 2007 President’s Cup was held on Royal Montreal’s Blue Course, which had also undergone a renovation overseen by Rees Jones. Although these renovations may be considered sympathetic to Mr. Wilson’s design intent, they were undertaken to accommodate top level tournament play and the distances and type of shots routinely played by PGA Tour players.

Dick Wilson Life History

The son of a dirt contractor, he was born in 1904 in Philadelphia, PA with the name of Louis Sibbett Wilson. He attended the University of Vermont for the 1924-1925 academic years, with a major in economics, but did not graduate from UVM. It has often been written that he was admitted on a football scholarship and played quarterback, but how and when that information originated is not clear.48 It is possible that Dick Wilson made those claims himself. Wilson’s first contact with the field of golf architecture was in the mid 1920s when he worked as a water boy at Merion Golf Club while the course was undergoing revisions by the firm of Toomey and Flynn.49 Wilson stayed on with Toomey and Flynn where he worked his way up to being a construction superintendent and eventually became a design associate of the firm.50 By 1931, Wilson was the lead construction supervisor for Flynn’s complete redesign of Shinnecock Hills on Long Island. His function was primarily to interpret Flynn’s plans and implement them on the ground.51 However, he was neither the actual foreman nor architect on the project and at one point, took it upon himself to deviate from Flynn’s design, which got him into a bit of trouble. Flynn came out to the site to “put Wilson in his place” and ordered the crew to rework what Wilson had done to conform to Flynn’s plans.52 Wilson although without formal training in golf architecture, had a background in construction work through his father’s profession and essentially learned the trade while translating Flynn’s designs and blueprints into golf holes on the ground. The actions by Wilson at Shinnecock did not get him fired, as he continued to build courses to Flynn’s designs until as late as 1937 with the Plymouth CC in NC.

In the early 1930s Wilson moved to Florida in order to oversee the construction of the Indian Creek Club in Miami Beach, Florida. The combination of the Depression and Toomey’s death combined to lead Wilson to seek other work as course projects were discontinued and the Toomey and Flynn firm disbanded. Wilson stayed in the golf industry, taking a job as the pro and greenkeeper at the Delray Beach CC.53 While at Delray Beach, Wilson met two transplanted siblings from Lumberton, NC, Pete Sundy and Daisy Sundy Meehan. Wilson visited frequently with the Sundys in Lumberton and became interested in the Lumberton Golf Course, a relatively primitive 9-hole course with sand greens dating to circa 1928. The course had been laid out by a civil engineer named J.W. Spruill who worked for the NC Department of Transportation. The course had been taken over by the town in 1934-35 and received funds for its upkeep through the Works Projects Administration. Wilson met the local pharmacist J.E. Johnson who became a Class A PGA Pro in 1939. Johnson was instrumental in keeping up the foundering Lumberton course. In 1935, Johnson, along with another NC DOT engineer, Cyrus Williams, and Wilson as the golf architect, spent several weeks redesigning the original 9-holer. The Lumberton Golf Course is now known as the Pine Crest CC and represents the earliest golf design work properly credited to Dick Wilson.54

His familiarity with blueprint interpretation and earthmoving led him towards the constructing and camouflaging of airfields during World War II.55 After the war ended, he returned to the golf business and formed a joint venture with the Troup Brothers, a Miami-based earth moving company. It was at this time that Wilson began to promote himself as a golf architect. His formal design credits begin in 1947 and include the West Palm Beach CC in Florida and the Kinderton CC in Virginia where he worked with Donald Ross, followed by a 9-hole course at Westview CC in Florida in 1949. As with most golf design firms in the late 1940s, business was slow, but by 1952, Wilson was successful enough to hire a 30 year old an associate named Joe Lee who had graduated from the University of Miami 1949 with a degree in education, and had taken up golf during college.56 Lee met Wilson at Lake Worth CC (which Wilson had just reworked); when Lee was the guest of club pro Vic Bass. Lee was on the practice tee when Wilson arrived. Wilson gave him a few pointers and they played the round together. Wilson subsequently invited Lee to Delray where they became good friends. It is not surprising that the two were drawn to each other. Lee had grown up in Florida on his family’s citrus farm and had always worked the land. He was, like Wilson, a top flight athlete, having competed for the swim team and been a standout baseball player. Golf came easy to him as well. Wilson hired Lee at Delray as a ranger, and let him give lessons, which indicates how easily Lee mastered golf, having just been introduced to the game.

In 1951, Moraine CC head pro Tommy Bryant spent the winter in Delray Beach and offered Lee the job of assistant professional at Moraine in Dayton, Ohio. Wilson had just contracted57 to design the 36-hole complex at the abutting National Cash Register courses and encouraged Lee to take the job. While at Moraine, Lee was naturally interested in the roughing out of the courses next door, and told Wilson that design work was what he was really interested in. Wilson responded that “you can’t design a damn thing if you don’t know how to move dirt.”58 Given his farming background, it is likely that Lee had some experience in this area, as he soon became responsible for overseeing construction of the two NCR courses. When NCR’s courses were completed in 1953, Wilson and Lee moved back to Florida where business began to flourish.

The late 1950s and early 1960s saw a boom in golf development not seen in the U.S. since the 1920s when close to 500 golf courses a year were coming on line. With the advent of post World War II earth moving equipment, the refined use of explosives, the availability of the new golf cart, and the lack of need for environmental permits, new course were appearing on mountainsides, in deserts, on former swamps and junglelands. Over 300 18-hole courses were completed in 1962 alone.59 Dick Wilson and his chief rival, Robert Trent Jones, were among those most in demand, especially in Florida where they competed for a number of projects. Although a number of golf courses were associated with housing developments, Wilson did not “believe in joint golf and housing developments, and he was all about pure golf. He didn’t even want to build ladies tees.”60 This divergence of views eventually led to Hagge’s split from Wilson at the end of 1962. After returning from Ohio in 1953, Wilson’s business picked up substantially, largely as a result of the reviews the NCR courses were receiving along with that from his work at West Palm Beach. He was awarded contracts for several courses in the Northeast, most notably Deepdale and Meadow Brook on Long Island, Laurel Valley in Pennsylvania and the new 45-hole complex for Royal Montreal.61 Rave reviews by Herbert Warren Wind about the newly opened course at Meadow Brook appeared in Sports Illustrated in the fall of 1955, and this further elevated Wilson’s status as one of the premier architects of the time. Meadowbrook evolved over several years from its opening in 1955 through 1967 as various pieces of adjacent land and the current clubhouse became available to the club. The club retains several original plans, including Wilson’s revisions from 1958 and 1962, along with Lee’s plans from 1967, which are closest to the current layout. These show Wilson and Lee’s adaptations to the evolving land ownership patterns at the club.

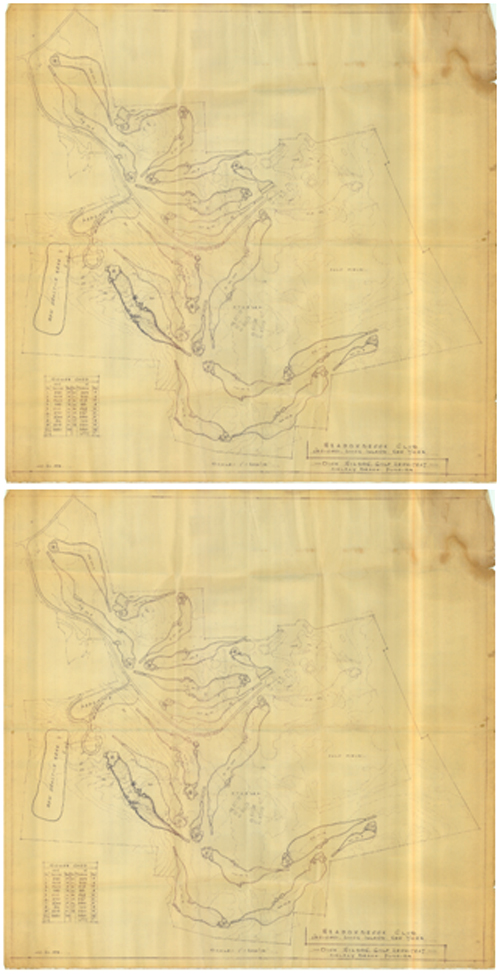

Wilson’s 1958 layout, top and the 1962 plan with partial rerouting, below resulting from the club’s purchase of additional land including the current clubhouse.

Twelth hole at Meadow Brook, left and the #15 runway tee, 79 yards long, at right. Top, the original 8th green with intact bnukers, now a practice area.

Numerous additional courses in the northeast included The Deepdale GC near Meadow Brook, The Garrison Golf Club on elevated and rocky terrain opposite West Point, the Cavalry Club near Syracuse, NY and Beden’s Brook CC near Princeton, NJ.

At Bedens Brook, the club’s 1975 history notes that Wilson “was chosen over Robert Trent Jones, who was also considered but whose initial submissions were inferior to those of Dick Wilson. It is a tribute to his talent that only four changes have been made in the course since it was originally constructed” in 1965.62 Since then a number of changes have been made, but the look and feel of Wilson is apparent right from the first tee with a view to the fairway bunkers and their ubiquitous islands within. The club retains a full set of copies of the “Original Greens Drawings” so it is relatively simple to identify exactly what changes have occurred and when. Although there are few runway tees, the routing remains intact with the exception of alternating 9 and 18. Ron Forse did a number of bunker and other renovations in recent years, and the club is focused on restoring as much of Wilson’s features as possible.

These courses illustrate Wilson’s versatility in working on varying environments, from the flat terrain ubiquitous to Florida, to the rolling parkland settings on Long Island to the rugged rocky terrain at Garrison. Wilson also knew how to handle the complex engineering aspects of drainage in both warm and cold climates.63 Wilson insisted that the greens at Royal Montreal be elevated, not only to give golfers an elevated target as per his usual designs, but to ensure an “effective means of surface drainage in the deadly ‘January thaws’ of a Quebec winter.”64

Below, Bedens Brook #5 Original Drawing, courtesy the Bedens Brook Club.

His list of original design credits (solo or with Joe Lee) in the U.S. runs to 58. This is a difficult number to pin down with complete accuracy. The list contained at http://www.worldgolf.com/golf-architects/dick-wilson.html totals 57, but includes some of his renovations as well as original designs. A likely more accurate source is the list found in Cornish and Whitten (1993) at pages 435-36, from which the associated text is derived. The Jackson Kahn Research Document lists 59, including original designs and remodeling. No sources currently list his early work at Lumberton. A further illustration of this type of uncertainty is at The Cavalry Club near Syracuse, NY where groundbreaking occurred on June 3, 1964. The course opened the following June and is generally considered a Lee design, but was built by Lee from Wilson’s plans.65

His U.S. renovations number 20. He designed the 3 courses at Royal Montreal in 1959, 8 courses during the early 1960’s in the Bahamas, Villa Real in Cuba in 1957 and traveled to Venezuela in 1958 to design Lagunita. He did renovation work in 1959 in Australia at Royal Melbourne’s East and West Courses, and returned to Australia in 1961 to renovate and add 8 holes at the Metropolitan GC.

The #4 greenside bunkering and #11’s runway tee at Deepdale. The bottom photo is the 18th green from #10 tee.

- #9, left and #17, right at Garrison.

Dick Wilson’s Design Philosophy

Wilson’s primary style involved letting the land dictate how the course would lay out. He noted that “you can put a beautiful woman in an expensive dress, but if the dress doesn’t fit, neither the woman nor the dress is going to look any good at all. It’s the same with building a golf course. You got to cut the course to fit the property.”66 He was heavily involved in not only designing a golf course, but in the physical work to lay it out. According to Wilson, “It takes a better man to build a course than to lay one out.”67 Wilson was of the opinion that a good golf course should require the full range of a player’s shots, instead of relying too much on elements such as putting or driving. His design theory was likely strongly influenced by his time at Merion, which he regarded as one of the finest golf courses in the U.S. because of its visually intimidating aspect, which requires considerable thought and the need for using many different shots, instead of focusing on length. “A golf course should appear more vicious to a player than it actually is, it should inspire you, keep you alert. If you’re playing a sleepy-looking course, you’re naturally going to fall asleep.”68 Roughly one third of his courses were designed on the flat land of Florida, which requires considerably more imagination for a golf architect to make a course interesting than is necessary on varied terrain.

He disliked blind shots or unseen hazards; when one plays a Wilson course, everything is laid out for the golfer to see, from fairway hazards to greenside bunkers. He moved away from standard round bunkers to a more feathered edge, which not only enhanced their appearance, but offered more challenging play to escape. Jones was fond of using round bunkers, so that was for Wilson, a good reason do design something different. Wilson tended to design large, rolling greens and incorporated mounding and raised putting surfaces throughout his courses, thus enhancing the generally flat Florida terrain with what is known today as vertical expression. Wilson, along with many architects of his period, often designed large greens with collars or tongues extending from the main portion in order to accommodate shots coming from the relatively low trajectory of a long iron or wood, especially on the longer holes, but often on the par threes as well. Today’s greens can be much smaller, given that modern equipment allows the top players (and the average golfer as well) to hit greens with higher lofted irons than was possible 50 years ago, and with more spin from the sharper grooves. The tongues or fingers might be areas of a green that were essentially peninsula shaped and could accommodate tighter pin placements than the main part of a green. Wilson would usually place bunkers or water hazards tight into these tongues to offer the player a more challenging, but rewarding shot if well struck. His bunkers were as a rule, 31” from the putting surfaces at Sunnylands, and the restored course reflects these elements.

He utilized long runway style tees, which allowed a course to be played at many different yardages, and worked well from a maintenance perspective compared with small tees. However, his design at Sunnylands did not include this type of tee, but had the more common (to that era) pods.69 Wilson did not favor the use of ladies tees, although these were incorporated by Lee and Cuellar after Wilson’s departure.

Wilson incorporated numerous doglegs, in some cases using them on virtually every hole. According to his chief rival Robert Trent Jones, “he builds too many doglegs. On some courses he’ll dogleg 14 of the 18 holes.”70 Wilson was somewhat formulaic in his designs, usually having water hazards on one third of the holes, landing areas at roughly 230 yards from the tees (the average drive of that era), bunkers and hazards close in to greens which required an accurate and lofted shot, and even incorporating specific distances from greenside bunkers to the putting surface. In the case of Sunnylands, 31” was the rule, which allowed for easy identification of greens that had been reduced over time due to mowing and maintenance practices.

Note that Doral’s #9 Red green above, was originally located where the current pavilion is today. Photo circa 1969. Courtesy Ryan Hershberger, Marriott Corporation.

Doral Blue’s #1 above left and the Blue’s #11, considered the #18 handicap hole on the course. View is from the middle of the fairway.

Dick Wilson’s Signature Course: the Pine Tree Golf Club in Boynton Beach, Florida

The Pine Tree Golf Club in Boynton Beach, Florida is widely considered to be his finest work.71 The original 1961 routing is intact and much of the look and feel of original course remains, along with 128 bunkers. The runway tees are present on every hole, including the longest one at 160 yards on the 16th hole, a 666 yard par five, which also happens to be the longest hole in the state of Florida. A single engine Piper Cub once made a successful landing on that tee.

The club remains strictly a golf club; there is no tennis or pool. Mr. Wilson considered it his home course, and until his death, he lived in the house (below) along the entrance drive. It is currently for sale, but does not come with a membership at Pine Tree.

The club remains strictly a golf club; there is no tennis or pool. Mr. Wilson considered it his home course, and until his death, he lived in the house (below) along the entrance drive. It is currently for sale, but does not come with a membership at Pine Tree.

The bunkering exemplifies Wilson’s use of elaborate shapes, multiple islands within bunkers, and numerous fairway and cross bunkers. Consistent with his style as well was making them all visible to the player. The course features two dog legs (there are rarely more on his courses) and many of his large greens with elongated fingers for tight pin placements. Although renovation work, including bunker reconstruction was undertaken in 1997 under Ron Forse and again in 2005 by Bobby Weed, the historic integrity of the course remains largely intact. Among the club’s archives are aerial images, original plans and numerous photos of each hole commissioned by Ben Hogan in the mid 1960’s.

Pine Tree’s first hole above, and #15 below. Note the uncharacteristic round bunker at left on #15, which is to be restored along with a number of similar atypical bunkers on the course.

The 12th hole, where Wilson incorporated a signature pine tree into the fairway. The tree has been periodically replaced to retain its strategic importance.

Below, two of Wilson’s play clubs on display in the clubhouse and his portrait which hangs in the lobby.

Conclusion

As evidenced by recent renovation and restoration work at many of the Dick Wilson solo designs and co-designs with Joe Lee, along with regular tournament play at his courses, Dick Wilson’s reputation is regaining ground. Between contemporaries Dick Wilson and Robert Trent Jones, Jones was by far better at public relations. His son Rees Jones has continued in his footsteps and further enhanced his name, whereas Wilson has had no such champion or descendants. His challenges with alcohol and somewhat ornery reputation have combined to overshadow his contributions to the field of modern American golf architecture. Without question, the hiring of Dick Wilson, arguably the most highly rated golf architect of the time, to design the course at Sunnylands, is an indication of Ambassador Annenberg’s intent to develop a state of the art private 9-hole course. Its restoration with the strong emphasis on retaining the historic character of the golf course as Mr. Wilson and Ambassador Annenberg envisioned it, should further enhance Mr. Wilson’s reputation, and solidify the characterization of The Course At Sunnylands as a significant historical and cultural landscape. The restored course and property as a whole would clearly satisfy the criteria for listing on the NRHP, should such designation be sought in the future. The restored course will constitute an outstanding example of a Modern golfscape.

—————————————————————————————–

1 History and period definitions prepared by the author for The Cultural Landscape Foundation. See http://tclf.org/content/golf-course

2 The first written reference to the game was in 1457, contained in a Scottish Parliamentary Order that imposed a ban on the game because the King’s archers were spending too much time on it, instead of practicing their bow work for the ongoing wars with England. The Sext Parliament Of King James The Third, Item 45. “And that the Fute-ball and Golfe be abufed in time cumming…”

3 Birnbaum, Charles A. Protecting Cultural Landscapes Planning, Treatment and Management of Historic Landscapes. 36 Preservation Briefs, National Park Service (1994).

4 Golf clubs have traditionally been organizations of people with the collective interest in playing the game of golf. The

course initially was anywhere the club played, and the location and character often changed each year depending upon whose land was available, which in turn depended on who was grazing their animals where and what crops were being rotated.

5 Price, Charles & Rogers, George C. Jr. The Carolina Lowcountry Birthplace of American Golf 1786. Sea Pines Company, Hilton Head, SC (1980).

6 The Dorset Field Club in Vermont cites a founding date of 1886 and golf has been played over the same grounds since that year. However, conclusive evidence in terms of written records from 1886 have not been identified. The St. Andrews Golf Club in NY was founded in 1888 and has been in continuous existence since then, but the course location varied in the club’s early years. Foxburg continues in its original location. Royal Montreal in Canada was founded in 1873 and moved to its current location in the late 1950s, when a new 45-hole complex was designed by Dick Wilson.

7 The five founding member clubs were The Chicago Golf Club in IL, The Country Club in MA, The Newport Country Club in RI, The St. Andrews Golf Club in NY and Shinnecock Hills Golf Club in NY.

8 Gutta Percha is a rubber like substance derived from the sap of the Palaquium genus of trees native to Southeastern Asian. It was originally used in Western cultures in the mid 1800s as an insulator for telegraph and electrical wires (including the first transatlantic undersea cable) as it was flexible and not prone to being eaten by marine creatures. It is still in use as filling for root canal work. In the 1840s, the substance, known as “precious gum,” was first adapted for use in golf balls. Known as the “gutty” it replaced the feathery ball (essentially feathers compressed and covered with a sewn leather case), as it was far less costly and flew considerably farther. McGimpsey, Kevin W. The Story of the Golf Ball. Philip Wilson Publishers Ltd. London (2003). Its first documented use as a golf ball was by Mr. H. Thomas Peter who won a medal event at Innerleven in Scotland in April of 1848. McGimpsey at page 10.

9 Labbance, Bob and Witteveen, Gordon. Keepers of the Green A History of Golf Course Management. Ann Arbor Press, Chelsea, MI (2002) and the Golf Course Superintendents Association of America. As gradual advances in technology sped up greens, architects responded by reducing slope and severity.

10 Various publications including GolfWeek Magazine develop lists of the top “Classic” and “Modern” courses, with 1960 being the point at which the “Modern” period commences. I prefer to categorize courses designed from 1945-1960 as Modern, given that there was little golf development in the US from the onset of World War II until the late 1940’s. Wilson was on e of few who did golf architecture work both before and after the war. In the context of Dick Wilson’s designs, the 1960 cutoff seems illogical given that one of Dick Wilson’s original designs (The NCR CC South Course in 1954) and one revision (Moraine CC A. Campbell 1936, D Wilson 1954) is listed on GolfWeek’s Top 100 Classic Course list (Laurel Valley CC from 1959 fell off the Top 100 for 2011), while Cog Hill #4 Dubsdread from 1964 is on their Modern list. Robert Trent Jones also has courses on both sides of the current divide.

11 The golf cart was patented in 1948. Car Care World War II Spawned First Golf Car. Golf Industry June July 1987 by Tom Rogers. See also, A Brief History of the Power Golf Car, National Club Association/Club Director January 1991 by Sheridan Much and. History on Wheels, Golf Industry, November 1991 by Kit Bradshaw.

12 Campbell, Sheperd and Landau, Peter. Presidential Lies The Illustrated History of White House Golf. Macmillan, New York, NY (1966). Pages 185-198. President Reagan had a forty year long tradition of playing at Sunnylands on New Years’ Eve.

13 The Period of Significance as defined by The National Register of Historic Places is “the span of time in which a property attained the significance for which it meets the National Register criteria.” Properties generally may be considered for eligibility fifty years after they are built; however, this is not a requirement if the property is of “exceptional importance.” Although Sunnylands is not seeking National Register status at this time, applying the NRHP criteria, it would most certainly meet all four elements. See generally, http://www.nps.gov/nr/publications/bulletins/nrb15/Index.htm Myriad golf courses and/or clubhouses are listed on the NRHP.

14 See the Currituck Shooting Club, listed on the NRHP, also referenced in McNaughton, Marimar. Outer Banks Architecture: An Anthology of Outposts, Lodges and Cottages. John F. Blair, publisher, (2000).

15 (Bucky Bowles http://www.hcc-al-ga.org/store ) to golf related destinations and locations. See Nelson, R. Resilient Form of the California Golfscape. Senior Project for a BA in Landscape Architecture at UC Davis, June 12, 2009, which discussed the need for alternative maintenance and design practices to make golf courses more naturally resilient in the CA environment. http://lda.ucdavis.edu/people/2009/RNelson.pdf See also, Zyl, Louise-Mary van. The Garden Route Golfscape: A Golfing Destination in the Rough. Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of a Degree of Master of Arts at the University of Stellenbosch (December 2006), which focuses on a golf tourism area in South Africa.

16 For a detailed description or sources and information, see Jackson and Kahn Research Report, January 7, 2010.

17 The image has somewhat poor resolution, but the bunker locations and number can be determined, and at 43, the number corresponds to DW’s January 1964 plan.

18 This image is has better resolution and also shows 43 bunkers. The relationship of the lakes and ponds to the green

locations is somewhat different than that shown on DW’s plan, but that is likely due to Tony Cuellar and his crew having

completed many of the lakes after DW’s crew had left the site.

19 TC noted that some of the work had not been completed when he arrived on site, including final shaping of some bunkers and completion of the lakes. As a result, not all aspects of DW’s original design were implemented.

20 GolfWorld’s Top 25 Best 9-hole Courses in America lists Sunnylands at #5. https://golfclubatlas.com/forum/index.php?topic=43301.0

21 John D. Rockefeller initially had four holes developed at Pocantico before 1900; the Country Club’s first course was six holes. Charles Blair Macdonald, considered the father of American Golf Architecture, designed his first course in 1892 as a seven-holer for Illinois Senator John B. Farwell. See Bahto, George. The Evangelist of Golf, The Story of Charles Blair Macdonald. Clock Tower Press, Chelsea, MI (2002).

22 Pioppi, Anthony. To the Nines, Ann Arbor Media Group, Ann Arbor, MI (2006).

23 Pioppi (2006) Introduction at page IX.

24 Pennington, Bill. Half the Holes, No Less the Charm, The New York Times. August 9, 2010. See also Pioppi (2006)

Introduction at page IX, and Whitten, Ron. Small Wonders, Golf Digest, February 8, 2010.

25 Pennington (2010).

26 Mackay, Robert B., Baker, Anthony K., and Traynor, Carol A. Long Island Country Houses and Their Architects: 1860-1940. New York, London: Society for the Preservation of Long Island Antiquities in Association with W.W. Norton & Company, 1997. Many private estate courses became membership based golf and country clubs. Others are now public or municipal. See also Silverman, Jeff. Personal Golf Courses, Travel & Leisure Golf, November, 2005.

27 Raynor, a surveyor by training, was working in Southampton, NY when he was hired by Macdonald to layout the holes at National Golf Links. He became a highly sought after golf architect in his own right.

28 The original course had been a rudimentary four holes, but Rockefeller brought in Scotsman Willie Dunn in 1901 to remodel those holes into a more formal 13-hole course.

29 According to Tony Cuellar, the course at Sunnylands was the realization of Ambassador Annenberg’s lifelong dream to build his own golf course. On-site conversation between Mr. Cuellar and Tim Jackson, January 2010.

30 Delong, David G. Sunnylands Art and Architecture of the Annenberg Estate in Rancho Mirage, California. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, PA (2010).

31 Although Dick Wilson is often listed as the architect of record, in many cases, he and/or Lee may have been primarily responsible for a particular design. In some cases, Wilson did the design and Lee implemented it on the ground, or vice versa. Wilson was the principle of the firm, but he and Joe Lee hand a handshake agreement that amounted to a 50% split on design fees by the early 1960s. See Whitten (2003). Therefore, the course at Sunnylands can just as easily be considered a Dick Wilson design as a Joe Lee design, although Wilson’s name is on the plans and the corporate entity under which they operated was Dick Wilson, Inc.

32 There is inconsistent information contained in various sources regarding who did what and when at La Costa. The Jackson Kahn Research Document notes that Lee added a third 9 in 1973 to complete the South course and the final 9 for the North course in 1986. Their primary source was La Costa Director of Golf Jeff Minton. However, Mike Bailey, a highly regarded golf writer who has worked at GolfWeek and for PGA Magazine, stated in 2009 that La Costa was originally 27 holes in 1964 and that Lee added the last nine in the 1980s. His source was then La Costa Director of Golf Dave Doerr. http://www.golfcalifornia.com/departments/coursereviews/la-costa-resort-spa-north-course-carlsbad-11165.htm

33 Bel Air Country Club A Living Legend. Bel Air Country Club (2003) at page 29.

34 The author’s father was among the first individual members in 1972. See Mendik, Kevin. Larry Wien’s Camelot The Golf Club At Aspetuck. Connecticut Golf Magazine (2002).

35 The Dean Estate Course in Ohio has six teeing areas playing into four greens, allowing 18 combinations, the Dee’s Place in New Jersey has six tees, one central fairway and a green on each end, Rees Jones designed Three Ponds Farm in NY with five fairways and four greens that can play as nine holes. Silverman (2005).

36 Brown, Gwilym S. Golf’s Battling Architects, Sports Illustrated, July2, 1962. See also, Sherman, Ed. Troubled Genius, Golf Digest, February 9, 2009. Robert von Hagge, an associate of Dick Wilson from 1955-1962 noted that he was the first to receive design fees in excess of $100,000. Jackson, Kahn Research Document January7, 2010 at page 30.

37 Cornish, Geoffrey S. and Whitten, Ronald E. The Architects of Golf Harper Collins, New York (1983) at page 435.

Originally published by The Rutledge Press in 1981 as The Golf Course. According to Neil Regan, Winged Foot’s Club Historian, many of the club’s records from that time were lost to a fire. Mr. Regan noted that Geoff Cornish was also on the property at that time. Personal communication October 6, 2010.

38 Why No Love For Dick Wilson, a June 2008 discussion thread in Golf Club Atlas, an online forum for golf architecture.

39 Wind, Herbert Warren. The Architect Makes a Golf Course Great, from Davis, William H. and the Editors of Golf Digest. Great Golf Courses of the World, Harper & Row, New York (1974), at pages 29-30.

40 Brown, Gwilyn S. Flags Are Flying Among the Palms. Sports Illustrated January 24, 1962.

41 According to Tony Cuellar, the superintendent who arrived on site in December of 1964, Wilson was “kicked off” the project because of a disagreement with Ambassador Annenberg regarding the use of particular fertilizers to grow in the greens. Jackson, Kahn Research Document at page 32.

42 Whitten, Ron. Gentleman Joe Lee 50 Years of Golf Design. Joe Lee Scholarship Foundation, Boynton Beach, FL (2002) at pages 18-19. See also Sherman (2009).

43 Brown, (July, 1962).

44 According to Cog Hill CEO Frank Jemsek, the son of Joe Jemsek, who initially hired Wilson. Sherman (2009).

45 Sherman (2009).

46 See http://www.cybergolf.com/golf_news/cog_hills_dubsdread_to_reopen_in_midmay See also http://www.coghillgolf.com/Dubsdread

47 After the first year of the BMW in 2006, it was collectively determined by PGA pros and tour officials that the course would need to be renovated and lengthened in order to continue to host a top tier PGA event. Although Rees Jones was sympathetic to Wilson’s original design, modern elements such as SubAir drainage and green cooling systems were installed, fairway bunkers were moved back to factor into today’s longer drives, and tee complexes were squared off and placed at various new angles and yardages.

48 According to Sylvia Bugbee, Bailey-Howe Library, UVM Special Collections, Wilson appeared on class lists during the 1924-1925 academic year and would have been among the Class of 1928. He appears in the UVM Yearbook Ariel in 1926 (the yearbooks were one year behind), but is not listed as being on either the freshman or varsity football teams. Personal communication November 9, 2010. See Fn. 51 below for similar reference ambiguities.

49 This account has been widely cited and was initially referenced by Herbert Warren Wind in The Meadow Brook Club’s New Course In Jericho, L.I. Has All the Hallmarks Of A ‘Born Classic’ of Golf. Sports Illustrated, October 31, 1955. Mr. Wind is one of the most highly regarded American golf writers of the 20th Century. He was known for fastidious research, and although his source was not identified, his reference is considered accurate. According to Wayne Morrison, the biographer for the as yet unpublished work on William Flynn and John Capers III, the archivist at Merion, there are no existing personnel records in the extensive Merion archives which prove that DW worked on Merion’s East course. Personal conversations with Mr. Capers III and Wayne Morrison, Flynn’s biographer (The Nature Faker, William S. Flynn, Golf Architect, published in electronic format, spring 2011), August 17, 2010.

50 Cornish & Whitten (1983) at page 435.

51 Although both The 75 Year History of Shinnecock Hills Golf Club by Ross Goodner (1966), and Shinnecock Hills Golf Club 1891-1991 by George Peper (1991) refer to Wilson as having designed the 1931 course, subsequent research as referenced in Fn. 46 above, has confirmed that Wilson was not involved in the architectural development associated with Flynne’s work at Shinnecock. See also, Cornish & Whitten (1983) at page 435.

52 This story was confirmed by William Flynne’s daughter in discussions with Flynne’s biographer, Wayne Morrison. 2010. See also, Why No Love For Dick Wilson, the June 2008 discussion thread in Golf Club Atlas as noted by Tom Paul, a past President of the Pennsylvania Golf Association and co-author (with Wayne Morrison) of the recently released biography of William Flynn. There are many instances where the on-site person doing the physical shaping must make field changes or simply determines that a particular shaping of the land may work better than what is actually in the field. The relationship of golf architect C.B. Macdonald (who designed the 1916 course at Shinnecock which had to be reworked in 1931 due to the construction of Route 27) and his surveyor, Seth Raynor, was replete with instances where this occurred, but their relationship was quite different, with Raynor being credited jointly with a number of Macdonald’s designs.

53 Cornish and Whitten (1983) at page 320. See also Brown, (July 1962).

54 Unpublished final draft history of the Pine Crest Country Club (FKA Lumberton Golf Course), dated September 30, 1999. Prepared by I. Murchinson Biggs, Esq. Although the exact year is somewhat uncertain, the course was expanded into 18 holes shortly after WWII. Mr. Johnson enlisted the help of Donald Ross to design an additional nine holes, but all the Wilson holes remained intact due to a shortage of funds. At the Tufts Archives, there are no plans or notes of Ross’ regarding work done at Pine Crest; however, a handwritten sheet of notes in the archives file indicates that Ross visited the site in 1946. The Wilson holes remain today as holes 1, 2, 3, 8, 9, 10, 11, 17 and 18. According to Head Pro and course owner Dwight Gane, Peter Tufts provided a concept for a 1990 bunker restoration plan which was implemented in-house. When I called Mr. Gane to tell him I was researching Wilson, he immediately stated “we’re his first course.” Personal conversation April 21, 2011.

55 Wilson’s experience as both a golf architect and a camouflager of airfields led to one of his most interesting

assignments: Project Greek Island, to hide the construction of the secret Eisenhower-era underground bunker, designed to house members of Congress and their staffs during and after nuclear attack. The 112,544-square-foot bunker is over 700 feet below the West Virginia Wing of the Greenbrier resort. All that dirt had to go somewhere, and Wilson was probably given the site’s topographical maps as prepared by the Army and asked to lay out a golf course to hide the hundreds of thousands of yards of cubic fill. His work camouflaging airfields may have resulted in connections with those responsible for the bunker project. The army contractors likely completed the work, as the finished product had few, if any of the type of intricate features normally associated with a Dick Wilson design of that era. The Army used Wilson’s name to give the course a degree of legitimacy. The Meadows Course (FKA Lakeside) opened in 1962 and was extensively remodeled by Bob Cupp in 1999. Personal communication with Robert G. Harris, Director of Sports and Recreation, The Greenbrier Resort. November 5, 2010. See also, Conte, Robert S., The History of the Greenbrier America’s Resort. Pictorial Histories Publishing Company, Inc. Charleston, WV (1998).

56 Whitten, (2002).

57 According to Lee, Wilson was given that job on the condition that he did not drink, as he already had a reputation for heavy drinking. Lee claims Wilson did not drink during the NCR development years, but was back on the bottle by the late 1950’s. Whitten (2002) at page 18.

58 Whitten (2002) at page 15.

59 Brown (January, 1962).

60 Golf Course Architecture Issue 12, interview with Robert von Hagge, April 1, 2008.

61 Wilson was given this job somewhat by default. RTJ had originally been offered the contract, but was unable to begin work on the project as a result of the club’s moving forward earlier than anticipated with the purchase of the land on Ile Bizard and the sale of their old land. Owen, Hon. George R.W. The Royal Montreal Golf Club 1873-2000. Royal Montreal Golf Club, Montreal, Quebec, Canada (2001) at pages 182-190.

62 http://www.bedensbrookclub.com/history.cfm

63 During the design of the course at Royal Montreal, Wilson had a strong disagreement with one of the club’s board of

directors who was insisting on using relatively new plastic piping for the watering system. Wilson slammed $1,000 down on the table, betting that the plastic pipe would not work. The bet was declined, the plastic pipe installed, and it promptly failed, resulting in a lawsuit. Brown (July, 1962).

64 Owen (2001) at page 190.

65 http://www.cavalryclub.org/newassets/cavalry-leaderboard.pdf. See also, Hamrock, Jarlath. Finger Lakes Golf Guide, Eastward Point Press, Willett, NY (2003) at page 135. www.cavalryclub.org

66 Brown (July, 1962).

67 Brown (July, 1962).

68 Sherman (2009).

69 Jackson Kahn Research Document (January, 2010) at page 33.

70 Brown (July, 1962).

71 Ben Hogan called it “The best course I have ever seen.” Sherman (2009).