Feature Interview with Frank Pont

January, 2008

Frank Pont is a late arrival on the European golf course architecture scene. After careers in Offshore, Strategy Consulting, Investment Banking and Venture Capital this Dutchman with an American twist has progressively been making his mark in the European golf architecture world over the last 5 years. Originally a competitive field hockey player who played in the Dutch youth team, he now regrets having only taken up golf when he was 18; it means his swing will never gain prizes for beauty nor will it ever become dependable. Also due to the yips and a virtually blind left eye his putting is abominable. Still he finds consolation in the fact that occasionally he manages to play his 8 handicap. Frank like so many at GCA loves the designs of the classic architects, and due to the fact that so many classic designs virtually lie at his doorstep in Holland, he has immersed himself in all things Colt, Simpson and Pennink. This has resulted in a large number of restoration projects of courses by these architects, and more recently his own design projects where he tries to carry on the torch of the strategic design tradition. Should yet another career ever materialize in the distant future, it wouldn’t surprise Frank that he would become an apprentice of photographic craftsmen the likes of David Scaletti and Larry Lambrecht. For more information, please go to his web site www.infinitevarietygolf.com.

You did not exactly follow the conventional path for becoming a golf course architect. Tell us about it.

I grew up in the Philippines and Brazil because my dad was an exp-pat for Philips. Given that the only good schools there were American, my first language became English and I only really learned Dutch when I moved back to Holland when I was six. After high school I studied Civil Engineeringat Technical University Delft and specialized in soil mechanics. After graduating with a MSc I went to work for Shell in Norway building offshore platforms on the North Sea. But constant rain and cold drove me to the States where I got an MBA from the University of Chicago, followed by five years in consulting for McKinsey and Monitor in Amsterdam. Finally I spent 6 years in London working in Investment Banking for Merrill Lynch and later Deutsche Bank, where I was head of their Telecoms group. This was quite an intense period, with 16 hours days and lots of travel (more than 200 flights a year), so I needed something that would allow me to periodically clean my head; this became golf. It was during this period I played a lot of courses all over the world and started reading the classics on golf design. At the end of this period in 2000 I was completely fed up with the job, lifestyle and travel , and decided to quit. My goal was to do something creative next, but I had no idea what (writing or painting seemed to far removed from what I had done before), so I spent a couple of months soul searching. By accident during surfing on the internet I came across a notice about the one year Golf Architecture MSc program in Edinburgh and I immediately knew that that was what I had been looking for. Even though I did not have a background in the golf industry, the fact that I had seen a lot of golf courses, had a background in civil engineering and could present myself well helped me land a slot in the 2001-02 program. I thus spent a year with 9 other golf nuts playing golf, walking courses, learning to design and last but not least spending time at the pubs! Overall it was a fantastic and very useful year. The only real disappointment was that the academic program itself was not great, and then especially the quality of staff. What also did not help was the total lack of real support by EIGCA and the lackluster performance of their visiting lecturing architects.

Your start in golf coursearchitecture came with David Kidd. How did that happen?

When I had made the decision to get into golf architecture I thought it would be smart to first get my feet wet and see if I liked the actual work in the field before I plunged into a year of studying golf architecture. I decided to write to the 10 architects I felt were the best in their field with the question if I could join them for a month or so (at my own expense) to get a feel for the work. As you can imagine the response was meager: 5 never even responded, 3 politely declined (Steel, Phillips and Norman) and 2 reacted positively (EGD and Kidd). Kidd’s was the first reaction, and amazingly came within half an hour of sending the e-mail. I was obviously startled to get his call, but later discovered this is his usual refreshing style of being direct. He had been triggered on my CV by two things: one that I like himself am a member at Machrihanish, and second that I was a banker. He was just in the process of signing the deal for Nanea and was dealing with the founders who are two of the most influential people in the US financial circles and wanted to better understand their mindset. He proposed a deal where I could be fly on the wall for a month at his project at Powerscourt, and he could pump me on various things financial and managerial. Being at Powercourt was great, and even though the contrast with the flying First class and staying at the Four Seasons of my banking days was stark, I loved every minute of it. Kidd made sure though I understood I what my place was; one of the first tasks he gave me (with a big grin) was to survey the new water level of a proposed pond forcing me to wade thigh high in the mud for an hour or so while checking the laser. I was impressed with Kidd’s personality and approach, and felt lucky to be allowed to repeat my experience working around him a year later when I was invited to join him and Paul Kimber at the Nanea project in Hawaii. Here again I spent a month walking around doing errand jobs and trying to learn as much as possible (and enjoying the rays!). The result was I was for good hooked on being an golf architect. For a while we tried to set up a continental European office for Kidd, but that did not work given his focus then on the US and UK, and since I did not want to have the extensive travel again that working for him would entail, we both agreed it was best to part ways. David Kidd was always extremely kind to me, and shared his knowledge and insights generously, and I will always be very grateful for the impact he has had on me at the beginning of my design career.

Your first solo project was at Eindhoven, your home course. What was entailed?

After I had started my own practice in Holland I was contacted by the board of the Eindhovensche to comment on a design that had been made by Donald Steel for the 16th hole, a medium length par 3 playing towards the lake and the clubhouse. The problem with this hole was that it had been destroyed by the Germans during WW II to allow them to store their light weight planes there (the fairway of the next hole, a par 5, was used as runway, and to this day the 17th therefore is the only flat fairway at Eindhoven). After the war the hole was hastily renovated by the members and green keepers, but it always sort of lacked authenticity and subtlety. The proposed design involved bringing the lake in front of the par 3 so that the shot to the green would play over water. I wasn’t excited about this idea, because in my view Colt never had a great love for water hazards. Not without reason does the whole lake at Eindhoven never come into play once, something which would be unthinkable for most modern designers given that site. I then showed the board about 100 pictures of par 3 holes by Colt, none of them showing water, but being quite consistent in many other ways. After that presentation it was clear that the water hole design was of the table, and subsequently the board asked me to design a more Colt style par 3 hole. The only condition they made (for budget reasons) was that I had to leave the green itself intact, something which wasn’t a big problem since funny enough the putting surface actually did fit in well with the existing other greens. However I did have the freedom to change everything around the green. The first thing I did was expand the number of bunkers from 2 to 3, to make the number of bunkers uneven, something quite characteristic for Colt. Second I made the defense of the green asymmetrical, which allowed for more diversity in the difficulty of pin positions. Third I raised the tees by about a meter and removed a lot of vegetation behind the green so that one could look over the green and saw the lake and clubhouse again. Fourth I lowered the surface in front of the green so that it visually seemed one was hitting into higher green, another Colt favorite. Finally I created a number of grassy hollows behind the green, another typical Colt design element often found around his greens. The hole reopened 3 months after the renovation, and has been quite popular since, even being voted one of Holland’s best 18 holes. This in my view is inflated; it is a good solid hole with beautiful views, but that’s it.

The sixteenth at Eindhoven, still with the lake only as a backdrop as Colt intended.

What made this first project extra special and somewhat sentimental for me was that my father had died on this exact hole of a heart attack some 10 years before; is there such a thing as coincidence?!

You then got involved with Kennemer, Colt’s first work in the Netherlands. The coastline of the Netherlands differs quite a bit from that along England; describe the opportunity that the land at Kennemer presented and how Colt made the most of it.

The coastline of the Netherlands has a dunes area that is significantly wider than that found in most places in the UK. In most locations the dunes are about 3 kilometers wide, in certain parts even stretching to almost 5 kilometers. Within these dunes there are many distinct types of landscapes, varying from the more typical relatively flat Links type of ground (found especially on the Wadden, a number of islands in the north of the Netherland) to the steep and very high dunes found near Wassenaar (where Royal Hague lies) and Bergen further to the North (no golf course present). The dunes land is so extensive and so well suited for excellent golf that one could easily have built 15-20 world class golf courses in the dunes and still not have really made an impact on the landscape.

The Netherlands enjoys a wide dune line for its coastline.

The land at De Kennemer lies more towards the spectrum of typical Links land, although even here some quite significant dunes are present.

Ironically, Pennink’s A nine, which is the the farthest from the ocean, enjoys the bigger dunes relative to Colt’s B and C nines.

The B and C loops which were designed by Colt, lying closest to sea but still a kilometer away from it, run through the more moderate dunes landscape, whereas the most inward nine, the A loop which was designed Frank Pennink, has significantly more movement through higher dunes.

Colt made a number of smart decisions on the routing. Fist he positioned the clubhouse perched on a hill with great views over the course. Second he routed the holes in two loops of nine holes.

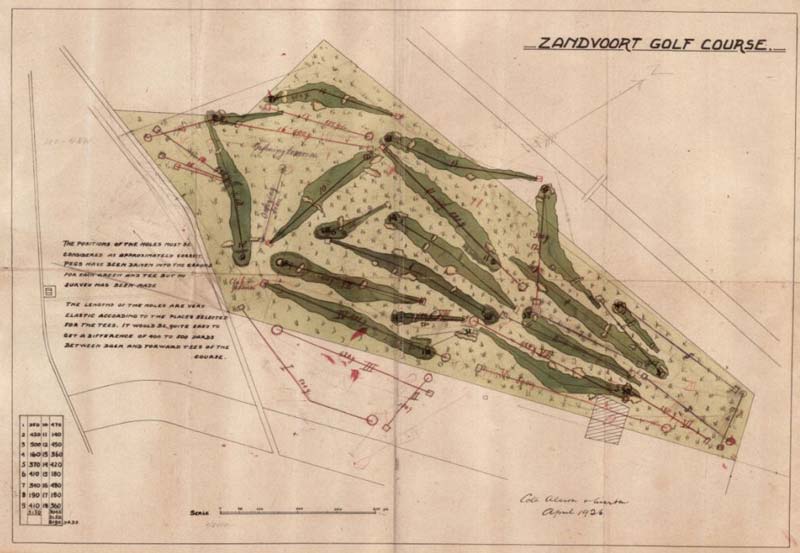

Colt’s routing of Kennemer with the inward loop contained within the bigger loop of the outward nine.

These loops both played out and back along a dunes ridge, and also both had to traverse the dunes ridge twice out and back. Third he was able to use one of his favorite design elements in abundance; the raised tee and green. Fourteen of his holes play from raised greens over a depression or lower fairway to a raised green. Finally because the existing soil was rather poor, and therefore there were a lot of sand erosion spots, he was able to build large natural looking bunkers.

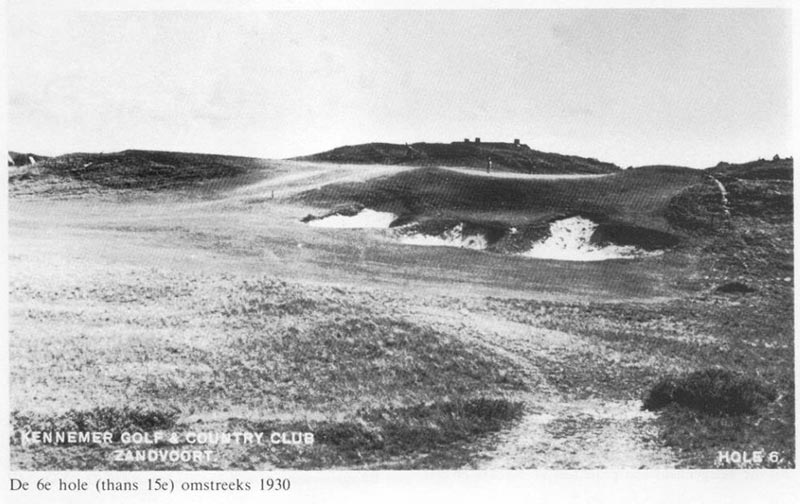

One of Colt’s favorite – and best – par threes is the uphill fifteenth hole at Kennemer.

Unfortunately the decision was made to cart in a lot of rich soil to construct the fairways (at Royal Hague the same was done), which did allow for green fairways from the start, but has caused the fairways ever since to be softer and less Links like than one would have liked.

Another problem was the fact that significant parts of the course were ruined during WWII, with a significant amount of (concrete) defense bunkers built throughout the dunes. This required that a number of holes and greens had to be rebuilt after the war, a process that took up quite some time. A hole that was very much influenced was C15, the special par three, where a bunker had been built in the green plateau. After the war the only way to rebuild the green was to raise it 1-2 meters and rebuild it over the bunker. Unfortunately the green now is rather flat, and the old natural looking bunkers have reverted into ordinary flat sand traps.

As seen today, the magic of Colt’s fronting bunkers at the fifteenth has been lost with time.

What work have you done at Kennemer? What work remains to be done?

I got involved with the Kennemer through Dolph Cox, their unofficial club historian and an absolute Colt aficionado, who showed me the complete correspondence between Colt and the club. They were looking for someone to help them make the Pennink designed green of B3 fit in better with the other Colt designed greens of the B and C loops. The green had a number of problems.

Pennink’s old B3 green had several issues, including the large pine front left.

First was that it was half behind a number large pine trees, something Colt would never have done. We solved that by removing the trees and reintroducing a hazard in the form of a bunker guarding the left front of the green. Second the green complex did not fit well with the landscape, but rather was a small hill lying separate in the landscape. This was remedied by moving sand from the right of the hole to the left of the green. Now the green surround was lifted on the left side with a drop on the right hand side, which followed the topography around the hole. This also solved the third issue, namely that the hole lacked interesting green surrounds from a playing perspective. The new grassy hollow on the right side of the green with short grass made missing the green with a long shot into the green a lot more daunting than before (this was shown in the amount of fumbles by players in this hollow during KLM Dutch Opens played here subsequently). Finally we also removed a levy that had been built behind the green to protect players teeing up on the tee of B4 behind the green of B3.

After Pont’s work, the new B-3 better fits with Colt’s other holes.

After this renovation I’ve done a lot of analysis but except for some tee renovations very little hands on work yet. Most of the last two years was spent working with the club making a detailed hole for hole course analysis specifying what elements of the course needed to be restored and how. Hopefully the plan will be approved this spring and work will commence full blown on the plan.

Most of the plan focuses on restoring Colt elements that had been lost over time. One example was the fact that over time many bunkers were added, removed or changed. This was established by comparing aerial pictures from 1938, 1956, 1966 and 1977. Most striking was the fact that in contrast to the original Colt design, where most greens were asymmetrically defended with bunkers only on one side of the green, most greens were now defended with what I call “pin ball machine” bunkering (bunker left and right of the green).

All of Kennemer’s bunkers, both the old and the new, are highlighted in blue above.

The other main issue will be bringing the bunkers back closer to how they looked when the course was opened,as opposed to the rather unexceptionally looking sand pits of today. This is a struggle since many of the club members do not see any need for this and furthermore the green keepers are strongly opposed to making the bunkers rougher again because they fear a maintenance nightmare due to sand blow.

Finally some of the back tees will be extended to make the course long enough for the best players (6500 m) and the A holes will be brought more in line with B+C in terms of bunkering and detailing around the greens (they tend to be much simpler than the detailing around the BC greens). Also the plan is to build a new green for A6 since the current green has a slope of more than 5% from back to front which makes it impossible to cut short and keep puts on the green (my guess this was a construction mistake not spotted by Pennink).

Overall work should take between 5 and 10 years to complete. This winter we will start with the first hole in the program, renovating the par 3 hole B8, where the work will entail removing the right side green bunker which is not original (and an eye sore), reshaping the right side of the green surrounds, restoring the green side bunker, lowering the hill left in front of the green and raising the tees to improve visibility.

After Kennemer, Colt’s next project was at De Pan, nearly a one hour drive inland. Given Netherland’s fame for being flat, how could an inland course hold much interest?

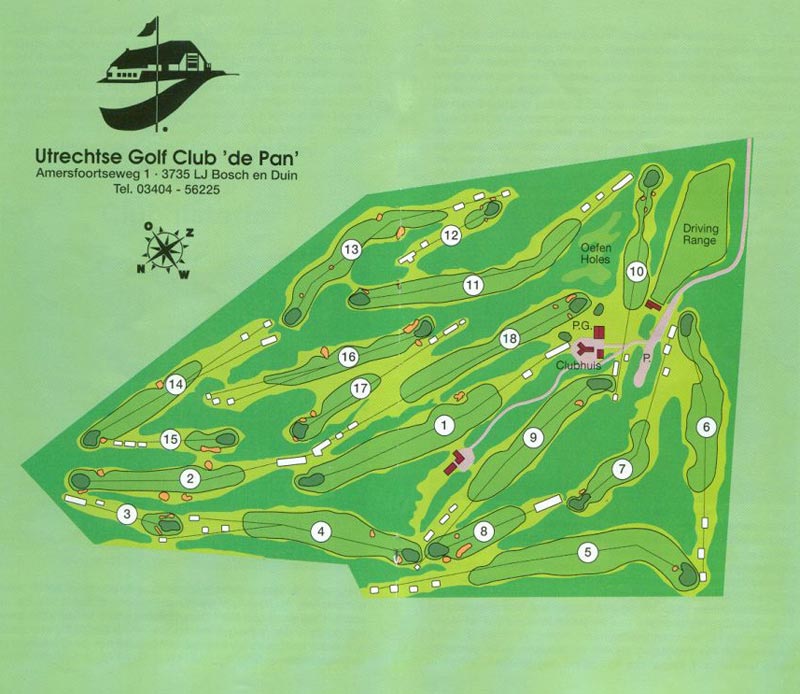

Your right that large parts of the Netherlands are flat, and often even below sea level, but certain parts do have significant movement in them. One such spot is the Utrechtse Heuvelrug (Utrecht ridge of hills) in the middle of the country, which was formed by glacial sand deposits left after the last ice age. Since this was extremely poor soil, it was never used for agriculture of for grazing, but rather remained forest or heath land. When in the early 1900’s people went to look for golf sites other than the dunes, it was logical that people would look at this area. De Pan was the first real golf course that was built there and was later joined by courses such as Hilversum, Hoge Kleij and the more modern layout Lage Vuursche. De Pan lies in a nature preserve of some 120 hectares, although the course itself only covers a rather small area of some 49 hectares. The vegetation consists of a mix of Scottish pines, heather and (less and less) sand erosion spots. The landscape has a rolling surface with a number of high dune ridges running through the property. It is the combination of a secluded feeling combined with very interesting but not too extreme topology that give De Pan its unique charm and character.

Tell us about the merits of Colt’s routing at De Pan and what ongoing work you are doing at the club?

The thing that makes the routing at De Pan so ingenious is that you feel as secluded on the course as you do whilst playing at Eindhoven, a course that is situated on a property three times as large. Most courses on 49 hectares would feel cramped, something you never feel at De Pan. The trick is the fact that Colt very cleverly used a number of dune ridges that run parallel through the property to separate the holes visually from each other, and the two spots where this wasn’t possible (holes 4,5,8,9 and holes 16,17,18) he created enough golf architectural interest that you forget about the seclusion (picture of routing of De Pan). The other thing that strikes you whilst playing at De Pan is the overall subtlety and refinement of the design of the course; it is a great course to play that lazy late afternoon summer round with friends, not dissimilar to the experience at a place like Swinley Forest. The third point are the individual quality of the holes, with some really unique and memorable holes. Examples are the 6th hole with a blind tee shot and a blind shot in to the green, the 10th hole with a unique feature of a bottleneck fairway, the beautiful 15th (almost a replica of Sunningdale Old hole 8 ) and the exciting drivable 17th hole with its highly positioned tee.

The work we are doing at De Pan is very much focused on trying to carefully restore the course. As someone in the Dutch golf world once famously remarked: “There are two things in life one should not mess with. Young girls and De Pan.” Unfortunately De Pan was touched a bit too much in certain areas in the past, which we are trying to restore gently over time. These are mostly the bunkers, a few tees and two greens that unfortunately were changed in the past.

Many of the bunkers were changed about 10 years ago when they got a somewhat American makeover (some of the visitors have likened them to Tom Fazio bunkers, with which I must admit I am less familiar). Here we are slowly but steadily bringing back the original oval shaped sand faced Colt type bunkers back that he was building during this period in the Netherlands. For this we are using historical aerial and ground photographs to assist us in bringing the old situation back.

An aerial drawing of Pan in 1947.

With the tees we are remodeling some of the tees that are standing out in the landscape to blend in better with the surrounding landforms. Finally in the past two greens were rebuilt (holes 5 and 7) that clearly are quite different in style to all the other greens. Both are likely to be restored back to their original forms as best as possible. Unfortunately we will have to work of old pictures since the old greens were never surveyed in detail before they were removed; the clear lesson here for clubs and architects alike is that if you want to change classic greens at least make sure you measure them up before you do so because otherwise you can’t revert back to the old design if the new design doesn’t work out ¦

Overall the restoration plan is scheduled to last a full ten years! That way we have the time to do the restorations gradually without too much disturbance for the members; De Pan has the time.. So far in the first two years we have managed to do holes 1 through 4 and we will also be restoring the green side bunker of hole 15 this winter.

Colt gets credit in name only for Royal Hague. Please explain.

Royal Hague was built in 1938, much later than the other Colt courses in the Netherlands which were all built at the end of the 1920’s (only other exception was Amsterdam Old built in 1934). By that time Colt due to his advancing age was not travelling very much anymore, and in the case of Royal Hague the work on site was done by Alison.

This however does not mean that the design therefore is purely Alison; Colt & Co worked too tightly as a group for that to be possible. Typically on other Colt projects of which I have read the correspondence (Eindhoven, Kennemer and Toxandria), the group would divide the site visits between them with Colt taking 60% of the visits and the others the rest. With the earlier Dutch courses Morrison was the man assisting Colt, and Alison only got involved in Holland later with Amsterdam Old and Royal Hague.

Nevertheless Royal Hague is different from the other Colt courses in the Netherlands. First of all the bunkering is larger, deeper and bolder than on the other Colt courses. Not only that but very few bunkers were used on the course, only one fairway bunker and18 bunkers in total. This was less than half the bunkers that Colt would normally use on a course and a third of what he used at Kennemer.

Furthermore the routing, and also the green locations were more adventurous, one might even say extreme, than Colt had shown in his work up to then.Royal Hague to this day remains a stern walk, and probably being a member there will add years to one’s life due to the healthy exercise. What remains quintessential Colt are the typical false flat looking greens, the beautiful shaping around the greens and of course the infinite variety and strategy of the holes.

How would you compare and contrast Alison’s work and that of Colt’s based on your experience in the Netherlands?

Hard to draw a conclusion based on one data point. For that I would need to take a closer look at what remains of Alison’s work in Japan, South Africa, Canada and the U.S. (and I hope I will get the chance one day to do just that!). But I’ll give it an educated try anyways.

From what I’ve seen of old pictures of his Japanese and American work here on GCA my conclusion would be that Alison’s style was a lot wilder, provided more drama and was tougher on the player than most of Colt’s designs, maybe even in certain situations quite penal/heroic. Royal Hague clearly gives one much more opportunity to lose a lot of balls than Kennemer, Eindhoven or De Pan do.

The other thing that is striking is that his hazards were built on a much larger scale, something I think he scaled back once back in Europe during the 1930’s (I think that without Colts moderating influence on Alison the bunkers at Royal Hague would have been even bigger and wilder).

The final thing I noticed being different from other Colt designs is the fact that a lot more of greens (15 out of 18) were crowned, making it easy for a shot not perfectly hit to run off the green.

What was your mission statement at Royal Hague?

Before I go into that let me first explain the problem the club was facing with their golf course. Royal Hague similar to Kennemer was built by carting in fertile clayish soil on to the areas of the greens, tees and fairways. This worked fine in the first decades and allowed for golf to be played in this otherwise barren dunes landscape, but became a problem in that in the winter the fairways are rather softer than one would like for a true links type course, but more importantly that the old clay layer after 70 years of topdressing on the greens had sunk so deep that it had become an impenetrable layer that could not be broken anymore with normal maintenance equipment.

The advice of a number of well known agronomists therefore was to build new greens. Royal Hague rebuilt one of the greens (hole 18), and although the process went OK they were convinced by the architectural issues that came up during this work that they wanted help from a golf architect with specific knowhow and experience in working with Colt courses. I was fortunate to be chosen from a number of architects who had been interviewed for the job, and got the mandate to design 17 greens, green bunkers and green surrounds. Thesehad tobe as close as possible to the originals in case of the greens that were still original, and for the greens and bunkers that were not original anymore I was asked to redesign them if necessary. Finally I was expected to be present at the club virtually all the time during construction of the greens in the summers of 2006 and 2007.

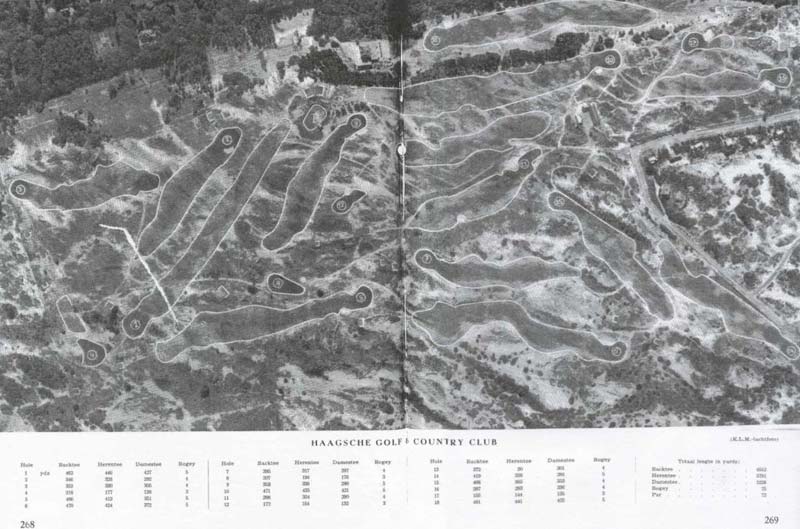

My goal at Royal Hague was to try to restore the original greens, their surrounding bunkers and the green surrounds as accurately as possible to the earliest pictures I had of the course (originally pictures from 1954, later even from 1946; the oldest aerial picture I found taken in 1938 unfortunately was made just before the course was built ¦).

Aerial of Haagsche in 1946.

The only changes I allowed were to correct drainage issues such as enclosed areas on the greens that did not surface drain and probably had resulted from variable compaction of the sub-soils under the green over time.

Even though you are keen to conserve Colt & Co’s work as best as possible, you elected to significantly change five green complexes at Royal Hague. Why? Please describe your thought process at each hole.

Of the 18 greens of Royal Hague 13 were still original, while 5 greens had been rebuilt or moved since the course was originally built. Three of these (holes 1,2, and 13) had been built by Pennink in the seventies, one (hole 17) by a local Dutch golf architect Rijks in 2001 and one (hole 7) by Kyle Phillips in 2003. We also slightly changed the green surrounds of the original greens of holes 8 and 16.

For the greens and green surrounds that weren’t original I gave myself more liberty in design, in that I set as my goal to create greens that would look and play like original Colt greens to a knowledgeable visitor. I will try to give an overview of the thought process per hole.

The only new green that we left virtually untouched was that of the first hole. This green could have fooled me of being an original Colt green, and given that I decided to keep it in its current shape. The only thing we did is remodel the green side bunker, which due to its banana shape clearly wasn’t a Colt bunker, and somewhat raise the entry into the green to make the bump and run shot into the green a little more demanding.

The green on the second hole was a different story; here the green complex obviously wasn’t original. The green was very small, all upward sloping and had an artificial looking band-like dune behind it. The hole is a medium length par 4 where the shot into the green, due to a massive valley in front of the green, either is hit blind with a short iron or visible with a medium length iron.

The old second green at Royal Hague…

I wanted to give the player hitting into the green with the longer shot more room to land on the green, whilst also making the blind wedge shot into the green harder. The other thing I wanted to achieve was to remove as much as possible the visual backdrops to the green so that the better player would have a harder time judging the distance to the green. The solution was to build a new green which was almost 50 percent larger, where the front of the green remained the old surface, but where a new back part was added that was first flat and after that sloped away from the player. This was possible by removing the little hill behind the green.

…and the new second green with its skyline green.

Finally I installed short grass grassy hollows behind the greens, which would both save most long balls from skidding over the edge to the much lower driving range, and at the same time would function as subtle hazards for the resulting up and down shots.

Royal Hague’s new second green as seen from behind. Alison frequently employed crowned greens at Hague and Pont successfully recaptured that aspect.

Solving the problem of getting the green on the seventh hole was a more problematic one. The main problem here was the same as that at hole 2, namely that the green was much smaller than the rest of the greens on the course and that it was impossible to keep it in good enough shape given the amount of play. Another issue was that during the previous renovation a final round of shaping of the green had happened after the green mix had been evenly spread, which had led to big differences in the thickness of the green mix layer giving maintenance problems. Finally a major headache is that all traffic on the course needs to go along the left edge of the green, since there simply is no other way to go, which makes it almost inevitable that a path right next to the green and in full sight is needed. The solution would seem simple, just like at green 2 just increase the size, and try to hide the path as best as possible. The problem however was that expanding the green was very difficult since the green was bordered by steep dunes on two sides and by deep ravines on the two other sides. The logical solution in the end was to LOWER the whole green by about 1 meter, which created just enough extra space on the right side to make the total green surface large enough. The green surface was kept relatively similar to the one before other than that a number of smaller undulations were removed to make it more consistent with the other greens on the course. The nice thing about expanding the green to the right is that it makes the tee shot even more strategic; any shot that is not left enough on the fairway faces a blind shot into the green.

A view of the old seventh green and…

…a view of the new one where 60% of the green is now visible.

The thirteenth green was quite a different challenge. This green was very out of character with its two-tiered structure and the double bunkering left-right of the green, both of which clearly indicate it wasn’t an original Colt green.

The hole is a difficult par 4, that most of the time plays into the wind. In designing the new green I wanted more space for players to land a long iron on the green and keep it there. This was possible by moving the green somewhat back whilst making it significantly longer. The new green is defended by a bunker on the right font side, flanked on the left side by a nice little nasty hump at the entrance to the green, which puts a premium on attacking the green from the left side of the fairway, a spot which is tricky to reach from the tee. The whole left hand side and back of the green is defended by three huge grassy hollows that will be swallowing most of the less accurate shots of the players. Putting on this long upward sloping green will not be easy either since it plays tricks with your eyes. From both the front as well as looking back it seems the green slopes left, something which obviously is impossible. As Simpson nicely said: “golf architecture is about creating difficulties, not explaining them.”

The sixteenth hole is a short par 4, which from the men’s tee is drivable for the big hitters. The green had a large pine tree right next to the green, which many members liked, but it had not been there in Colt’s days, certainly did not fit his design philosophy and most important was a maintenance nightmare for the green keepers.

The old sixteenth green at Royal Hague with a pine just right of the green.

So it was decided the tree had to go, and would be replaced, defense wise, by a new bunker, which also would bring the number of green bunkers up to three. To further increase the interest of the hole, the valley before the green was widened, so that dives or shots into the green that would slightly short would roll all the way down to the right hand side of the fairway, from which the recovery shot will be rather delicate and tricky

Though the photograph was taken in grow-in, the new sixteenth green is obviously a significant improvement, recapturing some of Alison’s flair for dramatics.

Describe the new seventeenth green at Royal Hague in more detail and what you like about it.

The last of the new greens is hole 17, the final par 3 of the course. Most people know that one of the things that set Colt & Co aside was the time they took to find the best locations for the par 3 holes in their courses. Almost all Colt’s par 3 tend to be excellent and interesting holes. If this is lacking, something has changed or been altered. That was the feeling I had when I first saw the old seventeenth hole of Royal Hague. The green wasn’t well visible from the tee, the green complex looked rather square and did not fit in the existing landscape that falls from right to left, and finally from a playing point of view the green only yielded a small number of different and interesting pin positions. Overall the old green complex was what I would call rather “one dimensional,” a disappointment for a par 3 on a Colt course, especially late in the round after so many fantastic holes.

The old seventeenth at Royal Hague was not a very exciting penultimate hole.

In designing the new green and its surrounding landforms I therefore wanted to achieve a number of things: It had to clearly visible, yet be visually deceiving. It had to have both easy and very hard pin positions. It had to be hard for the pro’s whilst playable for the elderly ladies members. It had to be very Colt, yet also be slightly eccentric in style compared to the rest of the greens up to then in the round. It had to be great for match play without being an automatic card wrecker. It just had to be very memorable, exciting and fun.

To try to achieve all this in a new design I started out by stating a number of things I wanted in the new green. First the front part of the green should be sloping upward so as to be very well visible from the green. Second the back left part of the green should be lower than the top plateau to create a hard to hit target, and to better blend with the surrounding landscape. Third I wanted to incorporate more bunkers, an uneven number of 3, with various degrees of difficulty and flashed sand faces to further make the defense of de green more varied. Fourth I constructed a number of short cut grassy hollows right and behind the green to catch slightly inaccurate shots and make the up and down shots more interesting. Finally I allowed for a less risk bailout area for the older members front-left of the green, from where a risk free chip onto the green was possible.

As seen from behind, the new seventeenth green has much more character now.

We will see how the end result will finally come out and play; the proof is in the pudding!

Is there any explaining how Colt came to dominate in the Netherlands and Simpson in Belgium? How do you compare Colt’s work in the Netherlands to that of Simpson’s in Belgium?

Hard to tell what exactly caused that, funny enough Simpson literally stopped at the French language barrier, since he did not build any courses even in the Flemish speaking part of Belgium ¦. If not the guttural language, maybe it was the poor Dutch food that put him off 🙂 ¦

It is hard to compare their work, but easy to see the differences in style. Colt was much more methodological and consistent in his approach. This makes it easier to tell quickly if and where things have been removed or altered on a Colt course. Gras faced bunkers, trees near greens or bunkers, symmetrical bunker defense of greens, even number of bunkers round greens, all are sure signs something had happened after Colt had left. Simpson was just much more, well, crazy. With him one can expect all kinds of strange things, although even he had a number of guiding principles, which however mostly centered around the strategy of the hole.

I find Colt the smart expert craftsman, Simpson the eccentric creative genius. Simpsons worst holes are far worse than those of Colt, but his best are in my view often even better than Colt’s best. Simpson was definitely better in building natural looking bunkers than Colt, and he and McKenzie might have learned a few tricks from each other’s work (if they ever saw it ¦). However I would have Colt do the routing if my life depended on it.

Comparing their work, I would say that Colt had the better draw with the sites he was allowed to work with (Hague, Kennemer, Pan, Knokke), but that Simpson did an excellent job of the less perfect material he had to work with. A course like Spa is an absolute joy to play, even though the soil isn’t sandy enough to provide for good golf all year round. His links at Oostende probably also was great before they put a highway right through it.

Overall I would say the main course of the meal should be a good staple of golf on Colts layouts, with some excursions once in a while to Simpsons work in the south to get a boost in creativity vitamins.

Noordwijk was the last links course built in dunes land in the Netherlands. When was that and is there any such chance another such links might ever follow?

Noordwijk was opened in 1972 and will most likely be the last real links course built in the dunes in Holland. The current European regulations are so strict, the water utilities (who own and control most of the dunes land) have no incentive to let any outsiders develop anything on their land and finally the sentiment in Holland that golf still is an elitist sport which will fence their golf courses off to the outside world at the first chance all doesn’t help. Two courses were built on two of the Wadden islands (Texel and Ameland), but these cannot be called real links courses because they do not lie in the dunes themselves but rather behind them in flat former agricultural land.

Nevertheless if golf keeps growing and becomes more and more popular (it now is the third sport in Netherlands behind soccer and tennis) who knows what might happen. Given that a project like Machrihanish Dunes went ahead, even though it was smack in the middle of pure dunes land that falls under the same strict European rules that don’t allow anything in the Netherland, means that that if the community really wants it, things can happen. In any case it will have to be developed with no or minimal earth movement, but with a great dune landscapes you really don’t need that in any case.

You’re involved in the renovation of a number of other Frank Pennink designed courses in the Netherlands. Could you describe the main differences between his style and that of Colt’s?

Frank Pennink, who had Dutch blood, was quite active in the Netherlands as a golf course architect. He designed more than 15 courses in Holland, many of them initially only 9 holes courses, which then later were expanded to 18 holes, often by Donald Steel. Penninks best designs are Noordwijk, which really is notch above the rest in quality, followed by Kennemer A holes, Rosendaelsche and Hoge Kleij, and then other designs such as Gelpenberg and Broekpolder. I’m working with 8 of these clubs, often focusing on trying to get the character of the two nines to better blend in with each other.

Although Pennink was an architect of the old British style, it is quite easy to see the difference between him and Colt. To state it bluntly his work was a lot less refined and strategic that of Colt, something especially evident when looking at the green complexes. His greens are similar to those of Colt, in that they are rather flattish with few undulations, but his greens surrounds are often uninspired and straightforward, often not connecting that well to the surrounding landforms. Also his bunkering, both at the greens as well as on the fairways was not very strategic. Many of greens have symmetrical bunkers left and right, and it could well be that he had a role in the bunker changes on the BC course of the Kennemer when he was involved with the club doing the A holes.

To be fair I think this lack of refinement often was also caused by the low budgets available to him to build the courses, which forced him to make concessions on certain design elements. I envision that he decided to focus on his greens and spend less time and money on the surrounds and bunkering, assuming he could always come back later to redo them when more money would be available. I have termed this approach the “Casco” method. The only places where he seems to have been given more money and where it shows were Noordwijk and Rosendaelsche. His bad luck was that he never got the chance to finish many of his Casco designs; however in a number of cases I am trying to make up for him by doing for him the best I can imagine some 20-30 years later, digging up green surrounds whilst trying to make them more strategic, natural and interesting.

How has the golf market developed in the Netherlands? What is the state of modern course construction there and what is your role in it?

The Dutch golf market is doing well, with large numbers of golfers taking up the sport every year. Golfers currently make up about 2% of the population, and I expect that number to double to 4% resulting in some 600,000 golfers. The problem is that there is an acute shortage of golf courses to play on for them, shown by the fact that there are currently 1400 golfers per golf course in Holland compared to an European average of less than 500 per golf course. If Holland with a 4% penetration rate reverts to an average of 1000 golfers per course this still means that there is demand for another 400 golf courses on top of the existing 200, something that will be extremely supply constrained due to the very long permitting times (5-10 years is quite normal) and the relative scarcity and high price of land. In this projected growth of golf a lot will also depend on us producing a number of top golfers. We now have 3 players on the European Tour, and the young amateurs are doing extremely well; in 2006 Holland won the World Cup for mens amateur teams in South Africa.

On the quality of golf courses things haven’t been as stellar. After the golden age of golf design in the Netherlands before the war, not much happened until about 5-10 years ago. Many of the 140 golf courses that were built in the period were pure functional affairs with flat unshaped fairways, holes mostly lacking any strategy, and in the worst cases built on sites that were too small with poor routings. The best of these were the designs of Pennink/Steel, but even these often depended more on the beauty of the surrounding than on the excellence of the design. The one piece of good news was that most of the green designs were good. Then about 10 years ago the first maturity started to come to the market with more demand for better courses. Lage Vuursche was built by Kyle Phillips and Belgian architect Bruno Steensels built De Goyer, two American style layouts that quality wise were a couple of notches above what had been built so far by the Dutch architects. More foreign led innovation and competition has led to a remarkable increase in the quality of the course that are being built nowadays. Main issue is the availability of high quality sites, meaning enough surface, sandy soil and interesting landscapes. I currently have about 10 really interesting 18 holes new build projects I am working on in the Netherlands, but then I have been fortunate. Most of the work in still on projects on uneventful flat polder land in clay or peat.

To tackle this problem of lack of good sites for golf, I co-founded a foundation (Natuurwinst which translates as Nature gain) last year which has as its goal to develop large nature reserves of over 150 hectares (400 acres) with golf courses interwoven in them. The other founders were the largest Dutch project developer, the most prominent landscape architect practice, a leading ecological developer and a golf developer. This has been very successful, we are now working on a number of huge projects, the largest involves 5 golf courses spread throughout a new nature preserve of almost 2000 hectares surrounded by a number of new country style villages.

Tell us more about thetwo Simpson designed courses outside of the Netherlands where you are working. Do you have more plans to work outside Holland?

I’m working at the moment with Cruden Bay in Scotland (where I’m also an overseas member) and Fontainebleau in France. I initially got involved with Cruden for almost two years now after reading a green committee report I found rather alarming. The reason was that it stated that they were contemplating changing a number of holes on the course, some of these holes being for the large part the reason why I had become a member in the first place. I then wrote to the committee and expressed my views on this, and to their credit the committee took it very serious and asked me to come along and explain myself on site. Now two years later we are involved in a multiyear restoration program for the course, trying to bring back the course closer to its origins, treading very lightly with any changes. One thing we already did was restore the entrance into the famous bath tub green of hole 14. What had happened here was that the slope into the green had grown so steep over the years that it had become virtually impossible to mow as fore green anymore and every ball would always make it onto the green. The reason became clear while we were renovating the entrance; over the years almost a meter of sand had blown onto the green entrance. The renovation work focused on restoring a natural looking and maintainable entrance to the green and at the same time also bringing the bunker in play more and making the tees of hole 15 safer by moving them further down the green.

The entrance to the one-of-a-kind bathtub green at Cruden Bay’s fourteenth hole.

Talking to the retired former head green keeper, he remarked that 30-40 years ago they would have storms blowing so much sand on to the green and its front that they sometimes would have to use a railway sleeper tied behind a tractor to pull the sand of the green!! After hearing that remark I was a lot less concerned with restoring the green surface exactly like at Royal Hague J ¦ One can safely assume the same forces of wind blow have similarly been at work at holes 15, 16 and 4, all of which are in the same zone of sand erosion.

Another thing we will be doing this year at Cruden this year will be building a spare par 3 hole, lying at the end of the property behind the green of hole 12 and the tees of hole 13. The hole will be a middle length par 3 playing down from the bluffs to a new wide but shallow green positioned on the last dune ridge before the beach and defended by three bunkers, giving the player a very exciting shot into green.

My involvement at Fontainebleau started differently, they had read and heard about my Colt/Simpson restoration work. This Simpson designed heath land gem an hour south of Paris has somewhat changed over the years, but still hold Simpson’s genius in abundance. I am currently working on a detailed course analysis, which will strive to restore some of the courses intricate style details (such as the lace edged bunkers, more heather etc.

I am indeed currently looking to expand my restoration work to more classic Colt and Simpson courses in Europe, and if sensible even further overseas. There are a large number of Colt and Simpson courses that could use support bringing their courses back closer to what their designers had in mind when the made the courses originally. My final goal is to work with 10 foreign classic courses and the 10 of the best Dutch and Belgian golf clubs in a few years time.

You founded www.golfarchitecturepictures.comone year ago. Why did you start it and what are your plans for it?

Over the years I had made a huge number of detailed pictures of many of the top golf courses in Europe. I was using these a lot as inspiration and in general to refresh my memory when I was thinking back on a certain hole of a certain course. The idea started when I was thinking how I could start sharing those pictures and make it sort of open source on the net. This quickly led a former classmate of mine, Chris Hunt, to also donate his collection, giving a total of almost 400 courses worldwide. The idea was to let people browse and download medium res images of golf courses. Usage has been huge, with almost a 1.2 million pictures viewed by some 12,000 unique visitors in 2007, something that actually has amazed me.

What however has severely disappointed me is the lack of cooperation by golf architects and other golf enthusiasts out there in contributing pictures. Other than Joe Bausch, and a number of others no one has contributed, while I’m pretty sure they are all browsing the site happily. Open source is taking and giving. The other problem has been the lack of time I have to keep the site up to date. As Joe Bausch can confirm it now sometimes takes me a while to get his new pictures on.

What I would like for GAP is to move to one size larger yet. This required two main changes: first for much more people to start contributing and second to streamline the logistics of contributing so that my interference isn’t necessary anymore. Maybe the way to do the latter is to have more people, say one per continent do what I’m doing now, and collecting and uploading pictures form their area to the central server. Money for storing the pics on the net is not an issue, $100 a year buys you 600 GB of space nowadays, a sum I’m more than happy to keep donating for this cause for the foreseeable future. Once this part of the logistics are settled one can start promoting the contributing of pictures through more channels such as the Golf Magazine’s and the clubs themselves. My goal still is to get to more than a million golf course pictures publicly online in the next few years.

The End