Feature Interview with Jaeger Kovich

February 2016

Jaeger Kovich is one of the talented young shapers coming out of the Doak and Hanse camps and is in the process of establishing himself as an architect in his own right. Continuing to build golf courses with the game’s leading architects, he is starting to work directly with clubs, whether for shaping, plan work, or consulting on issues big or small. Jaeger prides himself on a hands on approach that produces quality work at affordable prices. His web site is www.propergolf.net.

I am a big fan of Quaker Ridge. Others think it is overrated. You caddied there so you have an excellent perspective. Tell us your thoughts, especially now that Gil Hanse has it back to how Tillinghast intended.

I am such a homer for Quaker Ridge! She was my first true love. I had played a few great golf courses, and just finished an internship with (Mark) Mungeam Cornish Golf Design, when Rick Versure hired me to caddy at Quaker. It quickly became my answer when asked what my favorite course was, and I seemed to love it more every year as the club and Gil restored it.

Quaker has one of the best properties within a 45 minute drive from Manhattan. It also has a routing which takes advantage of its natural features in a unique way. The first 8 holes play in a “Reverse Muirfield counter-clockwise loop” with white soldiers down the right. Tillinghast provides golfers with some white-knuckler shots straight out of the gate such as the approach to the incredibly steep first green and the tee shot at the second. Then there is a massive change of pace as the course begins its interior loop. Suddenly the fear of right is removed, and the golf course takes on a new set of challenges as it enters a different part of the property.

Many of my favorite holes are found on the interior loop. Holes like # 9, 11, 13, 14, 15 inspire me as a golfer and student of architecture as they require so much thought from tee to green. Tillinghast challenges you, not just to be accurate and pick your side of the fairway on #11, 14 and 15 but daring you to get close to the hazards. A premium is placed on club selection with so many go for it or lay back decisions. How close do you drive it to the creek down the right of 11 or the cross bunkers on 14 or the creek on 15? This is as good as strategic golf gets in a parkland setting.

You also caddied at several other Tillinghast courses in the Met area. Give us – in order – your ten favorite Tillinghast courses in the area.

Tillinghast was my favorite architect growing up. I was lucky enough to play some of his best courses as I was developing an interest in architecture. Caddying proved to be a great way to gain access and study some of his other courses that I would never have been able to see otherwise at the time. It also afforded me the opportunity to return to places like Winged Foot, Fenway, Bethpage Black, and spend more time on the greens, while dissecting the strategy of his designs for some of the best local amateur and pro golfers. For a college kid fascinated with golf courses, I always looked forward to such opportunities.

Going by the list of Original Designs according to The Tillinghast Association, and accompanied by “my” Doak Scale number:

Winged Foot West 9

Sommerset Hills 8

Quaker Ridge 8

Bethpage Black 8

Ridgewood 7

Fenway 7

Winged Foot East 7

Bethpage Red 6

Baltusrol Upper 6

Paramount 6

Note* I have not seen Baltusrol Lower, or Sands Point Golf Club, and a few other examples of his work that may be worthy of inclusion in this list.

You have seen over 200 golf courses in eight countries since 2012. What does seeing so much golf mean to you? Does it help you grow?

The urge to see as many different golf courses as possible is part of who I am. There is something in my soul that makes me travel. In many ways I feel like it is my job too. The more I am exposed to different courses, styles, and features, the more ideas I have to draw on to influence my work.

The opportunity to study so many courses has been a huge help to me as my career has been progressing at the same time. It is very important to me to supplement all I have learned on site, in the office and by reading books with seeing as many courses as possible. There are different things about every course that will stand out to me and leave an impression in my mind. It can be something as broad as style, or a grassing concept. Other times it is a single feature that will leave a lasting impression. That is part of what keeps it interesting. You never know what you are going to find, and how it is going to relate to something you are working on at the moment or down the road.

For example, while working on the 18th green in China, we were trying to build a mound in the approach to get it to feel and play like a proper punchbowl. I wasn’t happy with how it was looking, when Eric Iverson (Tom’s lead associate, who is likely the best shaper in the world) and I took a walk back into the fairway to have a look. We were chatting away about how to edit it when all of a sudden he said he really liked the mound on Riviera #5 that creates a blind shot from the right side of the fairway. I looked at him, said, “I’ve got it” and away we went.

I have a rare ability to remember almost every hole I’ve seen, and that has certainly helped me in many ways. However, in most cases I find that it is the people involved that truly define each course to me. I have met many incredible people that have helped create, maintain and play a lot of these golf courses that have made all of the traveling worth it.

What is an example of a single feature you saw that you have locked away to use later in one of your own designs?

Wow, I can’t believe I am going to put this in print! I feel like I am giving away a secret weapon!

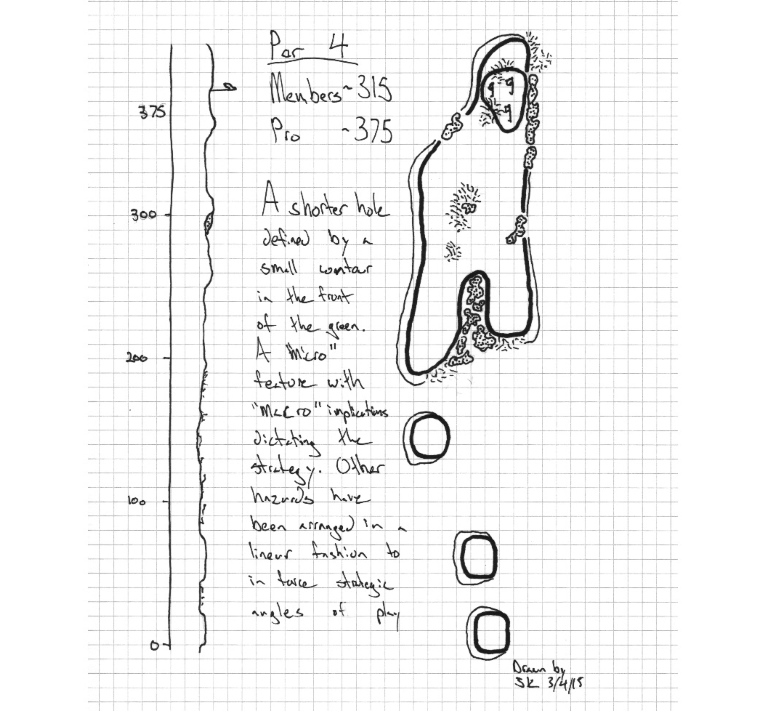

This feature has been at the very top of the list, in the back of my mind, for a long time. My sketchbook is filled with versions of this “template” hole and green based on this single feature. I love how this little feature dictates everything. It is a struggle to navigate on every shot. This is the first place where my mind went when Tom was holding his “Not The Lido Contest”.

The feature is the smallish knob jutting into the front of the 5th green at Friar’s Head Golf Club.

This is from the description for my “Not The Lido” hole:

A shorter hole defined by a small contour in the front of the green. A “micro” feature with “macro” implications dictating the strategy…

Who is your favorite dead architect?

My answer to this question has changed over the last few years. Tillinghast, the man responsible for the contouring of the first green on Winged Foot West, was my favorite for a long time. As I traveled more and was introduced to the work of Dr. MacKenzie at Crystal Downs and then in California, I fell in love again. His courses are so much more than wild green contours, camoflauge, and sprawling bunkers. What wooed me to Dr. MacKenzie was his artistic routings that are the true genius of his work.

The front nine at Crystal Downs blew me away; it is the best set of 9 holes I have ever seen. However, it was the routing at The Valley Club of Montecito that really spoke to me. I love the way Dr. MacKenzie used the two dominant features of the Santa Barbara property so brilliantly to create amazing interest, and a dramatic climax. Instead of using the best features to create one or two spectacular holes, he locates a number of greens and tees into the slopes and along the sides of the beautiful ridge with sycamore trees. This way the golf can interact with the most interesting part of the property as many times as possible. Then the golf begins to make its way back across the road, and a new sense of excitement begins to build.

Dr. MacKenzie uses the second dominant feature to guide the routing for the finishing stretch. However, this time it is not part of the natural landscape, but the amazing Stanford White clubhouse looming over this part of the property. As the golfer sets foot on the par-3 # 14th, Dr. MacKenzie’s symphony comes to a climax with the long-range view to the spectacular clubhouse. The next hole plays up to the spectacular building, and then turns away for a brief reprise, before the final hole plays back to its doorstep. On an otherwise difficult property, Dr. MacKenzie found a creative way to generate interest, suspense and drama at every hole using both natural and manmade features. It was this concept of using two dominant features, and especially the manmade aspect, that would help inspire my rerouting concept at The Village Club of Sands Point, which is also blessed with some inspired building architecture.

The long view from the 14th tee highlights MacKenzie’s optimal use of both nature and the impressive clubhouse.

Tell us the history of the Village Club of Sands Point. What are you presently doing there?

The Village Club of Sands Point was formerly the Gold Coast estate of Isaac and Solomon Guggenheim on Long Island during the roaring 20’s. Known as “Villa Carola”, the Italian Renaissance style mansion sits on a high point looking in one direction down to The Hempstead Bay, and in the other to the skyscrapers of New York City.

It had become IBM Country Club when The Village of Sands Point purchased the 210-acre estate in 1994, including a 9-hole golf course with some Robert Trent Jones influence in it. After an extensive planning process that lasted a few years, the course was transformed into 18 holes by Tom Doak, and Renaissance Golf Design.

I started working with The Village Club of Sands Point in the summer of 2014. They had contacted Tom interested to explore what it would take to move the current clubhouse from the barn to The Mansion. Coincidentally, I had just spent a few weeks in Tom’s Traverse City office learning about his routing process for The Village Club in order to help co-write a chapter for a potential book. Understanding the history of the golf course, and all the political and legal battles that influenced his design, was very important in coming up with potential solutions for moving the clubhouse. Tom kindly referred the club to me as I live nearby.

I presented the club with a plan to reconnect the golf course with the history of the site through the rerouting. Because of the way the course and property evolved over time, the facilities on the property feel a little disjointed. I was determined to find a routing that would use the site’s underutilized vistas along with the storied buildings to maximize the experience.

Jaeger’s handiwork in reshaping the bunkers is evident above at The Village Club of Sands Point, his first solo project.

While we wait for a final decision on the rerouting, the club had already committed to rebuilding their bunkers. I had a lot of fun reshaping them this past year. They were in need of some love. Along with an in-house crew lead by Superintendant Mike Benz, we did everything we could to improve them on a tight budget.

We still have three holes to go on the bunker project. We have purposely put off the holes near The Mansion for a little while longer until we have a plan in place for the bigger changes.

Tell us about Tom Doak’s course on Simapo Island in Hainan, China. Apart from it being set on an island, what were its design attributes?

Simapo Island was such a cool project. It has to be one of the most difficult and unique projects ever undertaken by Tom and Renaissance Golf Design. It was built on a 300 acre island in the middle of the Nandu River, where Haikou, the provincial capital, opens up into the South China Sea. Due to its location in the floodplain, there were a lot of engineering requirements that demanded huge amounts of fill. We ended up creating an entire landscape, not just a golf course in our giant sand box. Just because it required a few million cubic meters of earth moving doesn’t mean you can separate the influence of the site on the design of the golf course. This is the work and principals of Tom Doak and Renaissance Golf Design, known for site specific design and finding golf courses in the landscape.

What I really liked about the “story” of Simapo, as Eric Iverson, Tom’s lead associate for the project called it, was that we weren’t just engineering the site to withstand a 100 year flood event. The entire Island was designed to feel like it had been carved out by hundreds of years of river erosion. Now, river erosion and fast moving water does not leave behind linksy sand dunes, where wind blown sand creates humps, hollows and other shapes. River erosion uses massive amounts of force, cutting across the island. It deposits sand in a linear fashion along the path of the water, if it isn’t carried all the way out to sea.

Another unique part of the design was the interaction between the greens and the horizon. Finding different ways to play to, from, and alongside the water inspired a lot of the golf. Tom and Eric did a great job in creating variety by making you feel like you were playing down or level into many of the holes, rather than getting lost in the skyline with elevated greens.

The punchbowl 18th at Simapo Island with Nandu River and the ever growing city of Haikou in the horizon. Simapo would have been one of the most spectacular examples of golf in an urban setting.

What’s its exact status?

This is China we are talking about; nothing is exact! Last year there was a list of 66 golf courses that were deemed to be under investigation for their legal status by Presdient Xi Jinping and The Communist Party. Translation: You are shut down for an undetermined amount of time, and you are stuck in the Chinese vortex of not being officially labeled illegal. You are on the path to disappearing into the abyss.

The latest photos I have show that trees have been planted in every green, bunker, and fairway. All the bunkers have been grassed over as well. The most recent Google Earth image makes it appear like the irrigation system was shut off this past summer, which in many circumstances would be a death sentence.

I feel terrible for Mr. Han, our client. My understanding is that he still has hope that this is only temporary. For all of us that helped build the course, it is sad. However, I learned something towards the end of our project, before anyone had any idea what was coming, that I will carry with me forever in this business: All too often we do not get to go back and play the courses we build. Even if or when we do, chances are we won’t find them the way we envisioned them. The fact is, they aren’t ours and no matter how much we would like it to be different, all those things are entirely out of our control. To be really happy in this business one must truly love the act and process of creating the golf course.

A sad sight indeed: trees and vegetation have taken over these bunkers on the fourteenth hole. The bushes up on top mark the remains of a skyline green to the dramatic par-5.

Additional information is found here:

https://golfclubatlas.com/forum/index.php/topic,60801.0.html

China is a huge country with varying climates. Having said that, I lived in Hong Kong for a year and between the monsoon season and high humidity, how excited are we really supposed to get about golf there?

Unfortunately there is not that much to get excited about. Bill Coore’s Shanqin Bay is really good, and there are a few other solid golf courses on Hainan. We always had fun playing Weiskopf’s The Dunes on the Shenzhou Peninsula and two of the Mission Hills Haikou courses deserve a bit of recognition. However, I would not highly recommend a Hainan trip on its own even for the most die hard architecture fan unless you are already in that part of the world. I cannot imagine trying to organize a golf trip traveling through China. Getting from Haikou to Boao can be quite difficult and it is only ~ 100km away!

What were your takeaways from working on the Red Course at Dismal River?

The Red Course at Dismal River was eye-opening in terms of what minimalism can be. I was lucky enough to be one of the first people on site for year two. On my first day in Nebraska, three of us went out and played the course in its mowed out native state. And not much has changed since!

The golf course was mostly built by about 10 guys with rakes. Tom will tell you that no shaping was required for about 12 greens! It was amazing. If you ever wanted to learn how minimalism is truly practiced, go spend 5 months in the Sandhills with Tom, Brian Schneider, and Don Mahaffey.

Why do you think the Nicklaus Course there is so polarizing? I saw a lot to admire.

As far as the White Course goes, we were focused on building something different than what Jack’s team did, making it hard to judge it fairly. That said, what I admire most about it is that the Nicklaus team went out there looking to do something totally different to all their other work.

For some reason Jack and Nicklaus Design get unfairly stereotyped. If I had to give an award for the most improved architect over the course of a career, Jack Nicklaus would win hands down. While many still typecast him for the right to left tendencies and the high level of maintenance associated with his work, what I see is an entirely different take on creativity. Instead of digging his heels in and refusing to change, the best golfer of all time has made a clear and impressive effort to evolve. His work shows a maturing of his design philosophies. Taking chances and breaking away from the typecast mold, Nicklaus is now building courses that could not be more different than his early work. Courses like Sebonack and Dismal River define a significant shift in attitude and approach to golf.

Reinventing oneself is not easy, and Jack deserves a lot of credit for taking chances like he did in Nebraska.

As a shaper, please share with us your take on ‘good’ fairway contours versus ‘bad’ fairway contours.

There are so many places to go with this question. I could easily go on a tirade about containment mounding, my distaste for catch basins, and the importance of surface drainage, but what it really comes down to is the way the golf hole interacts with the landforms. Ideally you don’t have to build fairways: the definition of minimalism.

The best fairway contours relate to the overall landscape. They tie in seamlessly and use the most interesting parts to affect the way a hole is played. There are so many examples of golf courses going for the faux links look that have a lot of artistic mounding that don’t make it out of the rough and into the fairways. All that time and money [Don’t get me started on that subject!] is spent creating landforms that have little to no effect on the golf. Many of these courses end up with wild and rugged contours on the sides and pancake flat fairways down the middle, or worse, bowls littered with sopping wet turf and catch basins. The real golf elements don’t relate to any of those landforms on the sides of the holes. They end up looking incredibly artificial. On top of that, this containment-mounding concept repeatedly forces all the water into the fairways, when the goal should be to keep them dry.

One architecturally significant modern course that started to break this mold was Long Cove Club on Hilton Head Island. Is there a lot of created mounding on the sides of the holes? Yes, but here the landforms make their way across the fairway and relate to the bigger picture of the created landscape. There are no excessively rumpled contours perpendicular to the line of play, but Pete Dye and a laundry list of architects that cut their teeth working on his crew there offer hints and suggestions of these landforms throughout the golf course, forming a cohesive landscape rather than just a collection of individual features.

Note how the seventh fairway at Long Cove is rumpled throughout, including down the middle. The two and three foot humps and bumps force golfers to fiddle with their stance and set-up, helping the course to always remain ‘fresh.’

What is the thought process in shaping a fairway?

There is so much to think about when shaping a fairway. First and foremost my main concern when I get on the dozer, is where the water is going: surface drainage. Next, I’m thinking about what the ball is doing, what the effect of each and every broad contour or little knot is going to have on the ball. If I can accentuate surface drainage and create a contour that will help golfers gain distance by playing to a particular side of a fairway, or add a few inches and allow them to see a little more of green, then you are really on to something.

I’m also thinking about adding a shape to help explain a grassline, creating a shadow here or there to highlight a particular landform by drawing the golfers eye in that direction, and texture all come into play. You don’t always need to turn every hole into the 8th at Muirfield with the washboard like contours, but little hints that make it feel like the same natural events that caused the sand to pile into large dunes and ridges on the 3rd hole, also left some small interesting humps and hollows throughout the course, just at a different scale. In the end, one must always consider restraint.

One of the best shaping tips I ever got was actually a quote from the famous fashion designer Coco Chanel, “Once you’ve dressed, and before you leave the house, look in the mirror and take at least one thing off.”

Tell us about the transformation underway at Vineyard Golf Club on Martha’s Vineyard.

At this point, the transformation of Donald Steel’s faux links into the new course is essentially complete. When the course reopened in the spring/summer of 2015, all of the features were redesigned and rebuilt by Gil Hanse, Jim Wagner and “The Cavemen”. Some of the routing was changed, making the course significantly more walkable, as well as giving the course a few totally new holes, like #14, which turned out to be a really good short par-4. Even when some of the hole corridors stayed the same, greens sometimes shifted a hundred plus yards in places.

The course changed significantly, both stylistically and aesthetically. The faux links has been re-imagined, and the course now sits gently upon the naturally sandy Martha’s Vineyard landscape. Using a combination of sprawling sandscapes and more classically inspired features, the course offers a completely new experience.

The revised bunkering at the Vineyard Club better captures the natural sandy qualities of Martha’s Vineyard.

Last time I saw you, you were working on a ten foot deep greenside bunker on the Five & Dime hole at Ridgewood. Please update us on that restoration project.

I am happy to report, that just before Christmas, we finished reshaping and restoring the bunkering and green sizes on all 27 holes of A.W. Tillinghast’s Ridgewood Country Club. As the Met Area native I am, who was exposed to a lot of Tillinghast’s work early on as my interest in golf courses grew, the opportunity to come home and help the club, Gil Hanse, and Superintendant Todd Raisch restore Tillinghast’s work was a dream come true. It was a lot of fun restoring some of Tilly’s most impressive, and artistic bunkering. The intricate capes, and bays juxtaposed to the daunting trees provides for some amazing contrast and texture, producing an entirely different style and feel from much of his other work in the area. Tying it all back to your earlier question, I first saw Ridgewood looping during The Met Open in 2009.

The par 5 fourth hole on the West Nine at Ridgewood is one of two par fives on the property that features Tillinghast’s famous Sahara bunker. As seen above, its angled green favors approach shots played from the left side of the fairway.

You have worked for Gil Hanse on both new and restoration projects and Tom Doak on new course construction. How are their styles similar? Different?

Lets just compare New to New.

Both have similar working styles in that they genuinely encourage collaboration. I cannot tell you how rewarding it is to work with people who put their egos aside and are genuinely interested in finding the best idea. The team approach that both employ really brings about the highest quality work.

In my opinion one key difference is that Tom spends most of his time on site on foot editing, and Gil spends most of his time on site on a bulldozer. I really admire Gil’s philosophy that if he can’t get on the bulldozer and create, then he feels like he has lost the battle in his hands on approach.

Tom, who I have seen get on a bulldozer, is more valuable spending his longer visits editing the work in progress, and sinking his teeth into the next set of holes. His design associates (Eric Iverson, Brian Schneider, and Brian Slawnik) are normally the lead shapers. I have been so fortunate to be able to work alongside such talented and creative architects. There is so much of both Gil and Tom that I try to incorporate into my own work and process, reaching well beyond the design/shape philosophy. Whether it is their attention to detail, approach to how they run their business, or their non-stop work ethics, they have both taught me so much. I have been lucky learning from and working for the best in business.

Do you agree that restorations and renovations are likely to continue to dominate your profession for the next five years just as they have the last five?

Yes, renovation and restoration will continue to dominate the industry and keep it afloat. Some of these will be small projects aimed at fixing problems, while others will be more of the “blow up” nature as a semi-new build, and offer both the club and the architect the chance to dramatically alter the experience.

The new build part of the business seems to be almost an entirely separate profession. There has been some really high quality projects undertaken recently, and it appears that will continue in handfuls here and there.

Is that good or bad to you personally? After all, some people really just want to create something new while others are more happy to restore something close to population centers where courses matter to people’s day to day life.

I mostly fall in the first category as someone that loves the creative process. I enjoy being a part of a team, working together to create something new and different. I am always searching for ways to improve and hone my craft, and the best way to do that is by working alongside smart, talented people, learning about their creative process, bouncing ideas off each other, critiquing each others work, and pushing each other to get better.

That being said, I am happy to restore the work of some of our architectural icons on the game’s classic courses. Restoration offers the chance to use a different skill set and process. To be really good at it, one must find creative ways to problem solve at almost every turn in order to recreate. Every feature almost requires a forensic investigation in the dirt.

What is the one golf course that you wish you could say was your design?

Ballyneal Golf and Hunt Club in the sandy chophills of Colorado because of the emphasis on fun, and the influence of the landscape on every shot. Everything about the place epitomizes fun. As a lover of contour, I cannot think of a golf course where the ground has a greater effect on the golf ball. I am a big believer in the theory that the longer the ball is in motion, the more enjoyment one has playing golf. Ballyneal’s magical contours inspire you to get the ball rolling more than any course I have come across. Even more than that, Ballyneal challenges the golfer to use the course in ways that differ from the standard conventions. No golf course I have ever seen allows for such freedom and creativity.

You are 29 years old. People younger than you trying to get into the profession won’t see much new course construction. Wonder what the ramification of a continued paucity of new construction will mean in terms of the skill sets 10 and 20 years from now?

What it comes down to is that opportunities to learn on the job will become even harder to come by for the younger generation. The stakes are higher on new construction because they are rare, and often highly publicized. As a consequence, one ramification already developing is that the opportunities to shape greens from concept to finish are hard to come by, and thus this most important onsite skill is becoming harder to develop. While there will be chances to build bunkers with an excavator and knuckle-bucket, a skill that can also be learned through renovation, finding enough opportunities to practice the art of shaping with a bulldozer is going to be increasingly rare. A bulldozer can be the most impactful machine in building a golf course. Not only is it often the ideal tool to build greens, but it can alter a landscape faster than any other tool.

What I would say to anyone interested in entering the business over the next 20 years is there is always room for talent in this business, but it takes a lot of hard work as well as luck. I graduated from college in 2009, at the height of the “crisis”. I didn’t expect to see much new course construction either. I worked very hard. Reading all the books, I wrote hundreds of letters begging for an opportunity, but that was not enough. It took teaching myself Mandarin Chinese as well as learning how to run a bulldozer and excavator on my own before I got the chance to do it on a golf course. I have also been very, very lucky. Perseverance is something all the young talented people I work with have, and the ones a decade or two behind us will need it too.

Why did you start Proper Golf? Did you see a niche not being addressed (pun intended!) properly?

For a young and eager architect and shaper like myself, Proper Golf offered me the ability to make the leap into the next phase of my career. I started Proper Golf when I returned from China in 2014 because I fell in love with building golf courses. Architects had fallen into the habit of handing over very expensive plans to be constructed by an outside party or contractor over the last few decades. Today, thanks to modern construction equipment things can change very quickly, and having control over both the process and decision making is essential to building something great. There is no substitute for spending time in the field allowing for the design to evolve into its three dimensional form.

I love being on site, in the machines, creating fun and interesting golf. My approach to golf design is more like that of an artisan and master craftsman. I take a lot of pride in playing the role of both architect and shaper. I have learned first hand what it takes to build a world-class golf course from the absolute best. I know what it takes to go from concept, to roughing it in, and refining it all the way down to the smallest details by hand.

I founded Proper Golf so I could continue building golf courses with the passion and detail they deserve. If the people building the golf course are on site having fun, then it will directly translate to the amount fun golfers will have playing the course.

How will Proper Golf save clubs money?

It is quite simple. I am a trained architect and have a background in art – and love to draw. Yet, golf architecture doesn’t require excessive planning nor paper work to be great. In most cases, a concept plan detailed for budget purposes is all that is required. And yes, the occasional artistic rendering is a great tool to help promote the ideas to memberships. However, the extremes of detailed elevations and massive telephone book size reports for a simple bunker renovation do a huge disservice to the game. Clubs spend tens of thousands of dollars on reports rather than spending the money ‘in the dirt’ where it matters.

By letting the bulk of my work and process take place on site, not only do I save the club from paying for paper they don’t need, but the product is better as I react to what I am uncovering in the ground rather than sticking to a two dimensional drawing. By actively participating in the construction, I cut out the middleman and preserve the art that otherwise can get lost in translation. Additionally, I never take a percentage of the final cost for a fee – that pricing model whereby the architect makes more money if the club spends more is ill-suited to the club’s best interest.

With less backroom costs and overhead, and more time spent on an individual project, my company Proper Golf allows clubs to spend less and keep the focus on where it should be: solving problems in the ground.