Feature Interview with Harry Ward

May, 2019

Harry Ward fell in love with the sport at an early age, playing many rounds with his brother and best friend Alfie. Harry subsequently has spent much of his adult life giving back to golf by his research, writing and even reviving for several years a 9 hole Willie Fernie design. Harry is frequently found at major golf events across the United Kingdom, is a member of the British Golf Collectors Society and a hickory enthusiast. If you see a man carrying 5 or 6 hickory clubs (literally carrying his clubs sans golf bag which is how the sport was played its first several hundred years), then that might well be ‘Hickory Harry,’ a traditionalist in every sense! His latest contribution on the sport’s history is entitled Forgotten Greens, which tells the story of 500 defunct courses across Scotland. Laced with numerous appealing graphics, it also amply conveys the allure of being outside in Scotland a century ago, perhaps hitting a ball on a haugh or in a glen with friends. It can be purchased here.

1. What drove you to compile and publish Forgotten Greens, your recently released book on Scotland’s abandoned courses?

It all started in the early 90s when my late brother (Alfie Ward) whom you knew, began the research for the Biggar Golf Club centenary book. We had no idea we were about to uncover information of a visit from Old Tom to lay out and open our second course at Heavyside in 1901 (now defunct).

This little snippet alone raised our expectations as to what else may be hiding in the local newspapers or archives in relation not only to our main mission, the book, but also to other possible lost courses in our district of Lanarkshire. By the time we finished the Biggar book, we were in possession of all sorts of material in relation to no less than 15 defunct golf courses all within a 30 mile radius from our home town.

Alfie was pretty much a home bug and not too keen on travelling, so when I suggested tackling the rest of Scotland, which would have involved a lot of travel to the various libraries throughout Scotland (before internet and online newspapers), my idea fell on deaf ears. Plus, we were already considering the Arbory Brae golf course project which is well known to your readers (editor’s note: please read both Alfie’s October 2005 Feature Interview and Harry and Alfie’s February 2014 Feature Interview for additional information). However, I was smitten with the possibilities of numerous defunct golf courses all hiding in the library archival newspapers and decided to crack on by myself.

The key feature to finding so many unknown lost courses was really quite simple, although rather ambitious. I had decided, in my wisdom, that rather than search for target dates from books such as the golfing annuals, I would start a particular year of a newspaper in January 1st and not come out of that year of the paper until I got to December 31st, a herculean prospect ahead but one which had to done to alleviate any possibility of missing important information. I found that on a good day I could cover about four years of a weekly newspaper in a 10 hour shift (no breaks or loose your machine), but a daily such as the Scotsman was a different animal entirely, it could take weeks to complete, so much so, that I still have many years of the Scottish daily’s to complete.

As I was still working on a daily basis as an electrician, I would rush in from work and grab a sandwich or whatever and travel to any of the libraries which were within a one hour drive of my house, carry out my searches until the library closed and travel home again, hopefully with something worthwhile. The more distant libraries such as Inverness, Dornoch, etc. would have to wait until the weekend arrived and a five o’clock start to travel the 200 odd miles with an overnight in the car.

When I realised I was getting some good quality and never-seen-before information, my research changed into an obsession. I was becoming a collector of information on lost golf courses and could think only of adding another to the ever increasing list. I was also compiling a comprehensive archive on other aspects of Scotland’s golfing history as I went along and over the years this has grown to several thousand files, some typed and some not. The costs were beginning to spiral out of control with both fuel and A4 paper copies from libraries, some costing upwards of 50 pence a copy. I was knocking out hundreds in a day. I still have a shed full of paper copies awaiting transcription to my laptop, it will never happen, as I will not live long enough to complete the mission. I could do with some helpers!

2. When you started, did you have any idea that the number would surpass 500 abandoned courses?!

No, absolutely no idea whatsoever. I suppose that when Alfie and I found so many defunct courses so close to our home town, it should have been fairly obvious at the time that this trend should follow throughout the entire country, but the penny didn’t drop at the time.

When I started on the whole of Scotland, my original intention was to concentrate on the Scottish Islands for some reason, it was so long ago I forget why, perhaps its was the romance of some of the Highland courses that interested me, or perhaps it was due to the fact that one of the very first newspapers I researched was the Oban Times which covered some of the Scottish Islands. I have completed every edition from 1886 to the 1960s of this publication and the total of defunct courses as it stands today is around 800, with approx. 500 being featured in Forgotten Greens and a further 300 that need to be dealt with.

3. Eight hundred – that is hard to fathom! For a course to go defunct, it had to exist first and you note a pattern to how many of these courses were formed. Please explain.

As your readers know, the earliest Scottish courses were all of a linksland nature, close to the sea with the natural sandy machar ground, kept short only by rabbits and sheep. There are still some sites in Scotland where the true enthusiast of golf can simply turn up and whack away without pre-booked times or notifications and enjoy the game as it once was played on natural turf. One such location is on the Isle of Iona, and I can assure your readers that if they ever want to experience the game at its roots, then a summer’s day on the deserted links on the Isle of Iona is a must on their bucket list.

Of course, inland golf had to wait a little longer to develop, requiring a considerable amount of outside assistance to make it an enjoyable experience. Trying to play golf in a field of long wet grass is not exactly a fun day out, spending most of your time trying to find the ball, let alone hitting it, no, the inland game had to wait until we had invented the grass cutting machine in the mid 1800s. Some early inland clubs played their golf in the winter months when the grass was naturally shorter but this was still fairly unsatisfactory.

A considerable amount of my defunct courses were formed in the 1890s, which was not a coincidence. The game exploded in Scotland after 1880 due to several main factors, namely, the gutty ball, the grass cutter, trains, tourism, and good old fashioned vanity. I say ‘vanity’, as once the trend of the numerous new courses became apparent, towns and villages began competing against each other by laying out a course of their own in an attempt to attract the tourists. This situation also gave the local dignitaries (provosts etc.) the chance to show off their negotiation skills and carry through the arrangements to the successful opening of the course and get their name in the papers.

4. Please identify the typical qualities of the people who built the courses. Local farmers? The land owner?

Great question Ran. The ground of nearly all the golf courses, especially in the rural areas, was owned by well to do landowners, but managed by tenant farmers for agriculture or otherwise. This meant that in order to get a particular piece of ground for a course, the club or the organisers had to get the agreement from two sources, the owner and the tenant. The owners were usually quite keen to oblige in order to show their support for the local community and it was always a good move to get the owner’s wife involved knowing that she would probably influence her husband into supporting the project. This clever policy nearly always culminated in the lady of the house hitting off the first ball at the opening of the course.

The tenant farmers on the other hand were not so easy to convince, unless that is, there was a couple of shillings in it for them. Cattle and sheep grazing in the 1890s was a big deal with the tenant farmer paying a fee to the owner in the form of a lease. When a golf club came along and wanted to walk all over his fields with possibly hundreds of people, alarm bells started to ring. Even when a farmer agreed to a lease agreement with a club, he would have all sorts of conditions attached to it, e.g. his cattle and sheep remain on the ground and continue to graze, the grass will not be cut or interfered with in the summer months, greens and tees will be prepared solely by the agreement of the tenant, and an access route to and from the course will be strictly adhered to by the golfers. All of this ensured that the tenant farmer was now laughing all the way to the bank, just for allowing the golfers on to the ground and at the same time, giving up nothing. If a club did make a request to either cut the grass, remove cattle etc, then their lease would soar beyond their means.

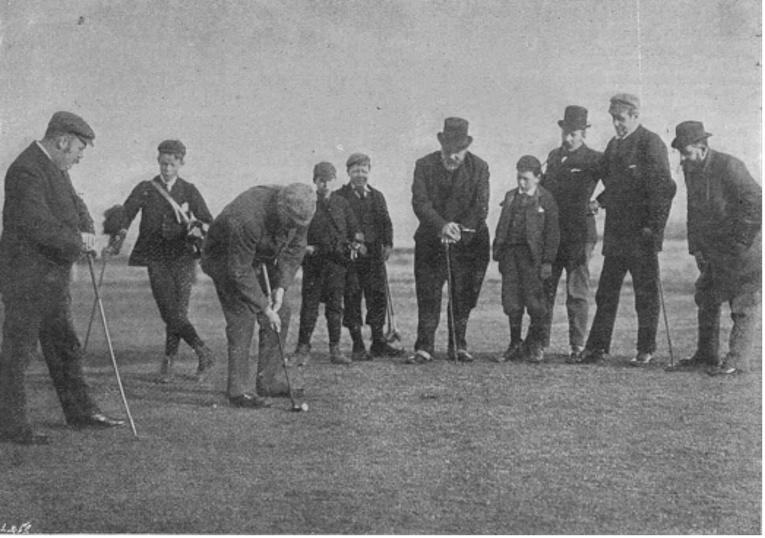

Many clubs played their golf medals throughout the winter months when the grass was shorter with less growth. As far as the course builders or designers were concerned, it was always a good practice to get some well known professional to lay out the course for promotional purposes, however, the professional laying out the course would simply walk the ground with the committee, armed with stakes and markers and instruct the committee where to place the greens and tees. This was just about all he did, leaving the club to carry out the work, and of course charging them a fee for his services.

5. You talk about the legends – Old Tom Morris, Willie Park, Ben Sayers, Willie Fernie – but few readers might have heard of Chief Constable MacHardy. Tell us about his role in expanding the game.

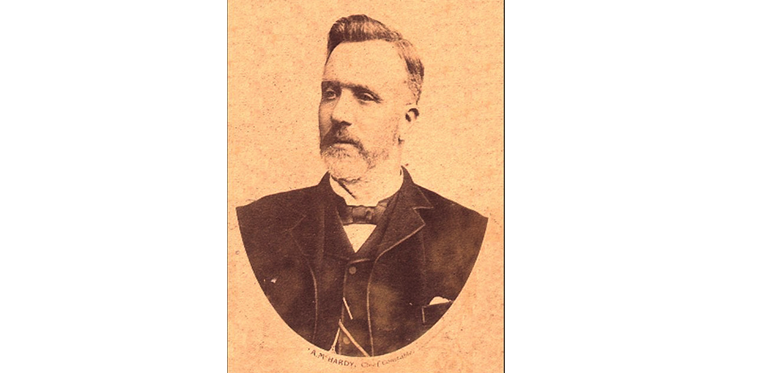

This guy has turned out to be a massive find as far as course architects are concerned. I think the best way I can answer this is to include an article I wrote for the British Golf Collector’s Society in their magazine “Through The Green” below:

Scotland’s Forgotten Golf Course Architect

The names of Scottish golf course architects trip off the tongue both because of their creations both at home and abroad. Willie Auchterlonie, James Braid, Willie Campbell, Willie Dunn and his brother James, sons Tom and ‘Young’ Willie, and his grandsons John Duncan and Seymour, Willie Fernie, ‘Old’Tom Morris, Willie Park Junior, Donald Ross were the most prolific, and there were many others, usually local professionals, who laid out a lesser number in their own surrounding areas. In Scotland particularly, James Braid designed some 45 courses, although he redesigned and altered many more. ‘Old’ Tom Morris laid out 42 and also redesigned many more, and Willie Fernie 32, with Willie Park and Ben Sayers responsible for around 18 each. Yet there is one man, as far as is known, completely unrecognised who, according to his obituary, was responsible for laying out over 100 courses. This by a man whose chosen career was that of a police officer – Alexander (Alister) McHardy.

Following his death, the Inverness Chronicle, on 2nd May 1911, carried the following tribute: “The death of Mr Alexander McHardy, Chief Constable of Inverness-shire and President of the Scottish Chief Constables Club, carries away from our midst another conspicuous and respected citizen. There was no man better known in the Highlands, or regarded with more esteem and affection, than Mr McHardy. Coming early to the front in the police force, he was for sixteen years chief constable of Sutherland, and for twenty-nine years Chief Constable of Inverness-shire, making a service as Chief of forty years. The qualities which Mr McHardy displayed in Sutherland as a young man, remained with him to the end. In the very year of his appointment, 1866, the late King Edward, then Prince of Wales, and the Princess of Wales, paid their first visit to Dunrobin.

In making the police arrangements on that memorable occasion, and in dealing with the crowds which gathered in the ducal grounds, Mr McHardy showed himself singularly happy and efficient. Riding on a handsome pony, dressed in a becoming uniform, he was to be seen everywhere, smiling, courteous, capable, and firm, keeping the ring, so to speak, without causing any annoyance to any of the eager populace. It was this combination of qualities that made him so acceptable to Royalty, and to the common people. The late Duke of Sutherland – who at first, we believe, favoured another candidate for the Chiefship – came to rely on Mr McHardy with complete confidence, and to honour him with his friendship. The Prince of Wales extended to him a similar privilege. Mr McHardy was in Sutherland during all the visits of the Prince to Dunrobin, and when the Prince became King, his Majesty was delighted to meet Mr McHardy again as Chief Constable of Inverness-shire. In his relations with the chiefs of Executive Departments, during the crofter troubles on our own county, Mr McHardy had sometimes to take up a position of his own, which he did with his accustomed suavity, but with perfect self-reliance.

The discussion of disputed points invariably showed the soundness of his judgement, and won the admiration of the authorities. To officials in the position of Mr McHardy, there is no opening in the ordinary life of the community. Fortunately he had the tastes which made him a pioneer and leader in the game of golf. He was, in fact, by constitution a sportsman, broad-shouldered and athletic. He took pleasure in every kind of physical exercise. A man of splendid physique, he was in his early days one of the finest athletes in Sutherland, and competed with success at many of the Highland Gatherings. On one occasion – in the early sixties – he stood second to Donald Dinnie, the World Champion, in the hammer and stone contest at the northern Meeting Games.

A native of Braemar, he joined the Aberdeenshire police in 1858, and in 1861 was transferred to the Fifeshire police, in which he was to become Deputy-Chief Constable. During his stay in Fife he acquired a love of golf, which he carried with him to Sutherland in 1866, when, in addition to his police duties, he became Secretary of the Sutherland Golfing McHardy Putting Out Society. The fine possibilities of the Dornoch links appealed to him, and he was not satisfied with having these links merely as a playground for himself and a few friends. so he applied for permission from the Royal Burgh of Dornoch for members to play golf over that part of the links of Dornoch which was the property of the Royal Burgh.

Permission was granted on 9 November, 1877 “Such permission being held by the society at the pleasure of the Magistrates and Town Council, who hereby reserve to themselves power to withdraw the same at any time if so advised.” Permission was not given to the burgesses of the Royal Burgh to play golf over the patrimonial lands of the Burgh, such permission being unnecessary because they had played golf over those lands from time immemorial. Permission was given to the Society, some of whose members may not have been burgesses, to play golf over the links. So the Dornoch Golf Club was born. The people of Dornoch were at first slow to see the merits of the game, but before Mr McHardy left the northern town he saw the course well laid out and the local club in a flourishing condition. This was the foundation of Dornoch’s prosperity. Mr McHardy considered that golf had been a boon to himself in carrying out the groove of official routine, and filling up his leisure hours. His enthusiasm was a genuine, honest enthusiasm, as he believed in the great value of the game, for health, for mental invigoration, and good fellowship. In 1882 he moved to Inverness to take charge of the County Police there and the following year he was one of those who attended a meeting to establish a golf club in Inverness. He was elected Club Captain of the fledgling club in 1884, a position he was to hold for 21 years, and President for a term, his relations with all the members being throughout of the most cordial character. To most of them his death was a personal loss. The Club moved into Culcabock (still its home) in 1886.

Unfortunately, Mr McHardy died before the 9 hole course was extended to 18 holes in 1914. Since he came to Inverness twenty-nine years ago, the game, largely through his efforts, has become so popular and profitable. It is believed that, at the request of club committees, he planned fully a hundred courses all over the country. As a player, Mr McHardy was a long driver and an excellent all-round golfer. He was also an accomplished angler, and an expert bowler and curler. He held office in the Inverness Curling Club, and gave admirable service in connection in connection with the bonspiels in the North. He also attended very regularly the meetings of the Inverness Field Club, and was president for a term. Mr McHardy was appointed Chief Constable of Inverness-shire in 1882, and lived to be the oldest officer in the police service. He died in harness at the age of 72. At the time of his appointment to the county of Inverness, the agrarian outbreaks in Skye caused great anxiety to the authorities, even if they were ultimately calmed down. A good deal of the credit was due to the homeliness and tact of Mr McHardy, and his knowledge of Highland character.

Quiet, firm discipline was exercised by him over his police force, with considerateness for the men personally that won their hearts. It was regarded as a public tribute to Mr McHardy’s services when in 1895, he was appointed a member of the Departmental Committee on Sheep Stealing in Scotland. Higher tributes were in store for him. When the late King Edward visited Mamore in 1909, his Majesty presented him with the Member of the Royal Victorian Order decoration, MVO, this interesting little ceremony taking place aboard Mr Bibby’s yacht. In July of last year Mr McHardy was summoned to Marlborough House to receive the King’s Medal at the hands of King George. The Chief Constables of Scotland were much gratified by the honours conferred on Mr McHardy, and they elected him as President of their Club for a second term. Two years ago the Club, of which he had been a member for 38 years, presented him with an illuminated address on the completion of fifty year’s service as a police officer. The officers and men of the Inverness-shire Constabulary showed their respect for their chief in January 1901, when Deputy Chief Constable Chisholm, now Chief Constable of Sutherland. Presented him, in their name, with a large framed photograph of all the members of the constabulary.

He was presented with a gold watch at the conclusion of his captaincy of Inverness Golf Club. The deceased is survived by Mrs McHardy and by two married daughters, the younger of whom is the wife of Mr Chisholm, Procurator-Fiscal, Lochmaddy. They have the sympathy of many old friends in their great loss. Mr McHardy, Chief Constable of Dunbartonshire, is a brother of the deceased. The funeral will take place on Wednesday at 2pm, from the Roman Catholic Chapel to Tomnahurich Cemetary. (Inverness Courier 2.5.1911) What can be made of the assertion that he was responsible for over 100 golf courses? Operating as he did in the extreme north of Scotland, Caithness, Sutherland, Ross & Cromarty and Inverness, it is hard to see how this sum could be amassed. These are, generally, large in area but sparse in population. To date, my research has so far verified 38 courses which he laid out. However, experience suggests that there could be considerably more. A lack of early records means that a number of clubs cannot say who designed their courses, but given that there were few experienced professionals in the region, and that Mr McHardy already had a good reputation as a designer, there is every possibility that he was called in; there are over 25 such clubs. Also, he was a good friend of the Duke of Sutherland and other landed gentry, and so it was likely that his help would be sought in laying out courses on private estates. These are much more difficult to identify as often their existence is only established by a casual mention in a newspaper. It is thus unlikely that the final number of courses he laid out will ever be established. And if the reputed 100 seems over generous, odd comments suggest the number may not be far short: “Mr McHardy, Inverness, who has now laid out over eighty courses during his life as a golfer, has recently visited Nigg and laid it out for an eighteen-hole course. Up till now it has been a nine hole course.” (Northern Chronical 11.11.1908)

So where does Alexander McHardy stand in the pantheon of golf course architects? If only the current 38 courses are credited to him, it gives him significant standing, but if anywhere near a majority of the reputed courses could be verified, he would be lifted into the front rank. It could be argued that the courses he laid our were simple courses which, in a number of cases, were duly redesigned in later years, but this would be a facile view.

He had to contend with some wild country quite unlike the softer land in the south, and he brought the game to people who, because of their remoteness, had little else in the way of recreation. After all to have the golfing eye to recognise the potential, and to select and arrange the nine holes which were, in due course, to become Royal Dornoch must establish Alexander McHardy among the leaders of the golfing architects.

McHardy’s Courses: Muir of Ord 1875 Dornoch 1877 Inverness Culcabeck 1883 Inverness Longman 1883 Fort William 1890 Castlecraig 1891 Kingussie 1891 Abernethy 1893 Bettyhill Hotel 1893 Eriboll 1893 Gualin Lodge 1893 Lairg 1893 Balintore 1894 Cromarty 1894 Dingwall 1894 Durness 1894 Fearn 1894 Helmsdale 1894 Inchnadamph Hotel 1894 Latheronwheel 1895 Laggan 1896 Insh & Kincraig 1897 Kincraig 1898 Fortrose & Rosemarkie 1899 Laggan 1899 Garve 1902 Bonar Bridge 1904 Fort Augustus 1904 Langwell 1904 Lybster 1904 Elgin 1906 Rothiemurchus 1906 Flichity Hotel 1907 Ardersier 1908 Balmacara 1908 Castlecraig 1908 Broadford 1909

6. Which three courses – regardless of number of holes – would have had the most ‘sophisticated’ designs? By that I mean which courses were feature rich? The article on Brough of Birsay Golf Links on Orkney notes that a ‘round bristles with hazards’ for instance.

I’m not sure that sophisticated comes into this as hazards in the 1890s were looked upon as Obstacles the golfer had to overcome as he made his way round the links. The more Obstacles or Hazards the better. This would get the course known as a sporting one. A typical hazard could have been almost anything from a dyke or wall, to whins, rushes, bogs, burns, rivers, trees, bushes, ditches, fences, or any other natural obstacle, and the description of Birsay links being “ the round bristles with hazards” simply means the links were abundant in these obstacles. It is interesting that you picked out Birsay, as it had a clifftop hole where the ball had to be carried sixty yards over the sea from tee to fairway, and with a gutty ball too!!

A modern view of the links at Birsay. You can see the sixty yard carry on the left between the two cliffs.

Another unusual course was the first Sanquhar course in Dumfrieshire. Every one of the nine greens was protected by a four foot wall which the player had to negotiate.

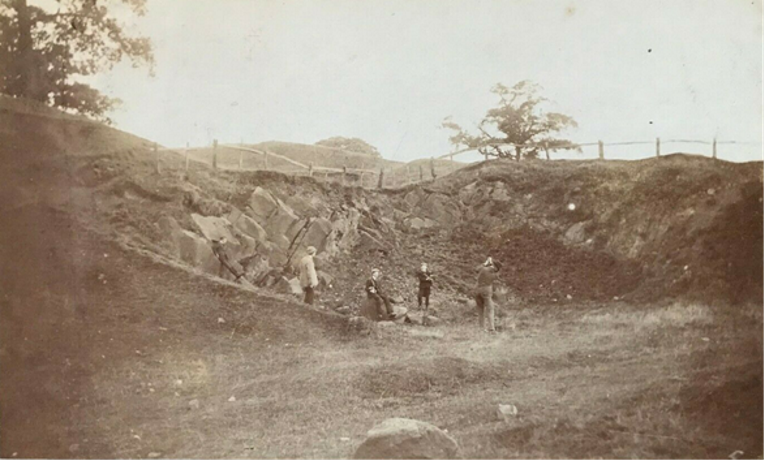

At the Bilston course of Polmont, near to Edinburgh, the 25 acres of ground were littered with small 10 foot deep quarries approx. 30 foot in width. The club quite simply placed most of the greens (9) immediately behind the quarries meaning that should the player come up short, he was playing out of a 10 foot deep hole.

7. Which three courses do you most wish were still around?

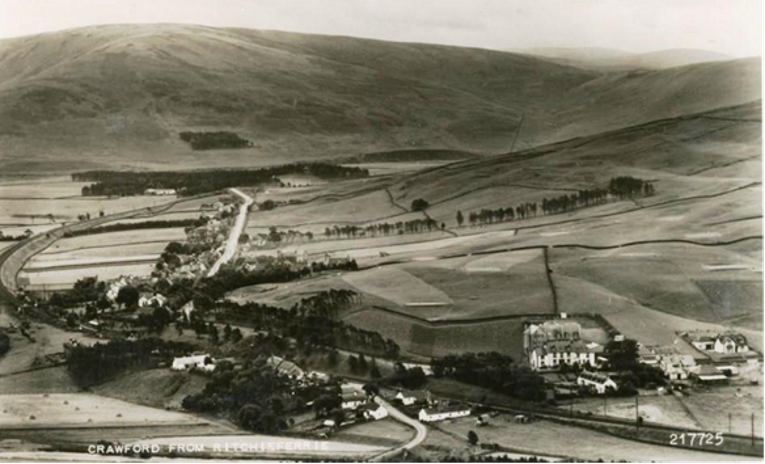

Well I don’t even have to think about the first one, its got to be Crawford. Crawford was the jewel in the crown of all Scotland’s inland courses. Laid out on a hillside by Old Tom in 1888, this course had it all and was light years ahead of the rest for its time.

An 18 hole course with a yardage of over 5,600 yards in 1890, it was a monster to play with a gutta percha ball. The club had an active team of 20 Volunteers keeping the place well groomed and the greens were massive compared with other courses. The club laid out a separate nine hole course for Ladies and Juniors in 1892, making it one of the first 27 hole facilities in the world. The course had a higher section on the hillside and a lower section near the village. The lower section was beautifully contoured with small hillocks and valleys, all of which survive to this day. The scenery from the higher ground was unsurpassed.

The second would be Laggan’s first course in Invernesshire. The course was laid out immediately above the village of Laggan and was opened by the famous Andrew Carnegie who lived in the nearby Cluny Castle at the time. I’ve picked this course because of its spectacular views of mountains and heather clad hills. It also has a river flowing through it and two of the tees were placed very cleverly beside a waterfall.

I first visited this course on a Sunday morning in June 2015. After an early rise at 5am and a four hour drive I arrived at Laggan at 9am to the depressing sight of mist covered hills all around and low visibility. Laggan is just a tiny little highland village and on a Sunday morning there was no one to be seen. I was sitting in my car adjacent to the village church with a cup of tea when my window was tapped, good morning I gasped at the sight of the local minister about to open the church for his Sunday service. When my mission was revealed to the minister, who was also a golfer, he encouraged me to cheer up and not to worry about the overcast morning, assuring me that all would be well and the day would brighten up before long.

I left the car and climbed to the high ground above the village to where the course was situated. I had an old layout sketch of the course to follow and before long had located the approx. position of the first tee. Now, I’m not a religious man by any means, but the scene which unfolded in front of me was stunning, and the minister’s words were ringing in my ears, it will brighten up before long. Sure enough, the mist was clearing to reveal a valley with a backdrop of mountains in the distance and the old Laggan golf course beneath my feet. I was approx. 30 feet away from a running stream with a waterfall which was obviously the location of one of the tees as described in the Oban Times newspaper. My four hour drive to this remote location had now been justified!

The third is Loch Assynt in Sutherland, and again it is the scenery which takes my breath away. Part hillside, 5 holes, and part low ground for the remaining 4 holes. An old ruined lodge, an old ruined castle, a beautiful loch with mountains as a backdrop. Surprisingly, I don’t have an awful lot of information on this course, but I do have a remarkably detailed layout sketch of this course from 1912, which allowed me to trace the steps of my golfing forefathers in Sutherland. One of the unusual features of this course was the 3rd green which was located on an Island and accessed by the golfers with a steam launch.

8. Of the 500+ courses, what was the typical number of holes?

I reckon that about 85% would have been 9 hole courses, and 10% 18 holers, with 5% being 6 hole courses or otherwise. Nearly all these courses began life as 9 holers, and through time many progressed to 18.

9. You highlight a group of courses in your book that I had never heard of – the lighthouse course! Presumably, these had the fewest number of holes as a group?!

Yes, and for obvious reasons, a lack of space, although the Isle Of May on the Fife Coast had six holes.

10. Another intriguing grouping is that of the private estate course, of which a staggering 118 have been abandoned. Do you have a favorite among them?

One particular course which springs to mind is at a place called Murthly Castle in Perthshire. The footprint of the course is still intact and the first tee is located adjacent to a ruined castle, an existing fairy tale castle, a river, and a woodland of beautiful tall pine trees. The entrance to the course is via an avenue of ancient trees with the castle at the end and the course to the right, and just to add a bit of exclusivity to it, here is why the course was laid out in the first place:

Murthly Castle Golf Course, The Scotsman August 21st, 1901: The Grand Duke Michael of Russia arrived at Murthly Castle on Tuesday evening, attended by an equerry. It is understood that his imperial highness has come for a few days golf. His host, Mr Fotheringham, is a keen golfer, and has recently laid out an 18 hole golf course on his grounds. Among the house party are Sir Cuthbert Slade, Bart, ; Captain Murray, Abercairnie; Mr Claud Strachan Carnegie; Colonel Lionel Benson; and Mr Gilbert Elliot.

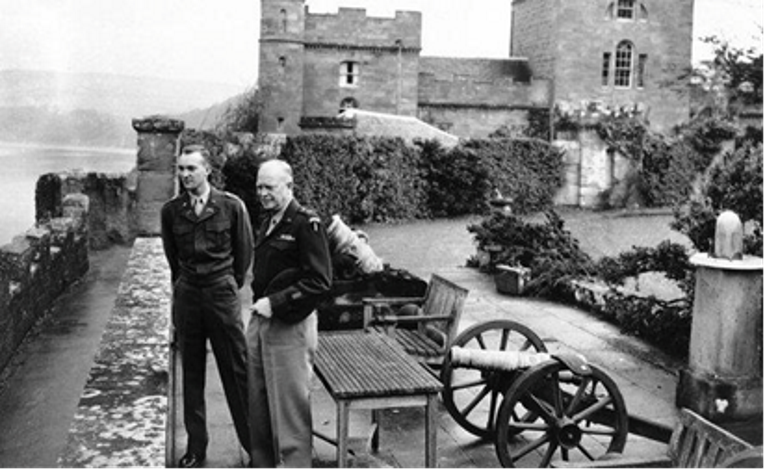

Another amazing private golf course was at Culzean Castle in Ayrshire. The course was laid out in 1893 for the 3rd Marquess Of Ailsa who was captain of the Prestwick club in 1899. As was usual with the aristocracy of the time, the Marquess spent a lot of his summers in France and became a member of the Pau golf club at Plain de billere, where he was coached by the professional Dominique Coussies. The Marquess was so impressed with Coussies that he invited him to Scotland to lay the course out and continue the lessons.

The course was laid out in the deer park with streams, ornate bridges, and all sorts of grand flowers and shrubs. It was a mini-Augusta. The course was ploughed up during the first world war, but was re-laid out and extended by James Braid in 1927 on the same ground. As a result of his WW2 leadership, Dwight Eisenhower, a devoted golfer, was gifted an apartment in the castle, which he used, and he was known to have played the course on several occasions. The course closed in 1941.

There were many beautiful private estate courses in Scotland at the turn of the century which entertained the rich and famous with frequent visits from Royalty, however, nothing lasts forever, and most of these lavish locations closed in the 1930s, when the well to do owners began to be financially squeezed by new government tax legislation and window tax etc. I hope this small sample portrays the grandeur of a forgotten era of golf history.

11. It does, it does! You note, ‘Nothing goes on forever, not even the Scottish golf courses.’ Talk to us about how improvements in transportation meant that locals could travel farther for a better game if their local course was unsatisfactory.

Prior to 1900, the mode of transport was more or less three fold, bicycle, train, or horse and trap. Although the motor vehicle started to appear at the turn of the century, it was quite some time before it was affordable to a large proportion of the populace. The bicycle had its obvious limitations due to the state of the roads, as did the horse and trap, with a good horse managing only 20 miles or so a day. This left the train as the main mode of transport and many of the golf courses negotiated discounts with the train operators to get the golfers to their locations.

The rail network grew so fast that by 1905, almost every town and village was accessible by steam train and all the daily requirements (food etc) was delivered to the various stations, including the morning papers etc. From around the 1890s up to the first world war, many of the golfers from small rural village courses were unaware of most of the other golfing locations which lay outside their territory, with the exception of those which had been promoted in their area newspaper. These tended to be courses within a 20 mile radius.

A good example would be the courses which existed in my area of Lanarkshire, 15 in total, all within 25 miles of each other. All these clubs played matches and socialised with each other, but rarely did any of them go further afield for their golf. This trend continued well into the 1920s when the car began to make an impact. With improved communications and information, the golfers began to realise that the grass might be greener somewhere else and so the exodus by car or train from the small rural golf courses began.

12. Suitable course conditioning was no easy matter to achieve. You have this line ‘The Haugh is still too much under grass to admit to a first-class game, and local players are indebted to neighboring clubs for the occasional round on their greens.’ Another course seemed destined to bog-like conditions. How many of the abandoned courses do you think were built on ground ill-suited for the game and therefore were almost destined to fail from the start?

Your readers have to understand the golfing public’s mentality in the 1890s. By that I mean that, when they were playing their golf on what was their little piece of rural paradise, they had little or no idea of what was good or what was unsatisfactory, as they had nothing within a reasonable distance to which to compare their course. Most of the courses which collapsed in the early 1900s, did so for several reasons, but not because they were ill-suited for the game, as you put it.

The great war had a huge impact on course closures with most of the club members not returning from the front, and also courses being ploughed up for agriculture for the war effort. A haugh in Scotland is a piece of flat low lying ground beside a river or stream, which is prone to flooding in the winter months when the water levels are higher. In question 4 above, I remark about the value of grazing in the 1890s, and how getting a piece of ground to play golf on was not always easy. A few acres on a haugh did not command such great value to either the landlord or the tenant because of its poor quality. As such, it was easy to give up for the golfers, however, not very many of my defunct courses come under this category. The most prestigious of any golf course on a haugh would be the course at Advie in Invernesshire which was played over by the Duke Of York and opened by Mrs Sassoon, the millionaires.

13. In your book, you stress the important point regarding golf and its therapeutic qualities. Please talk about the Gartnavel Hospital (Glasgow Royal Lunatic Asylum) as an example.

(From the book) Yes, golf had been introduced to many of the mental institutions and asylums by laying out small nine hole courses on the grounds of the hospital. Conventional thinking had been that these courses were intended for the staff, and only rarely for the patients. Yet the therapeutic value to a patient of a round of golf was recognised, and this was spelled out by the Commissioners in Lunacy Scotland annual report of 1878 which emphasized the use of the asylum estates for treatment rather than simple isolation, hoping that outdoor recreation would act as a deterrent from morbid thoughts, distracting and engaging the patients mind through mirroring the entertainment found in “ordinary” life. Tennis courts and cricket pitches appeared first and golf was to come later. The Gartnavel Hospital (Glasgow Royal Lunatic Asylum) was perhaps the largest such institution in Scotland at the time, and led the way, opening its golf course in 1893. The course was used by doctors, nurses, attendants, and patients, and ladies in all categories. Gartnavel was one of 17 similar institutions where golf was used as a healer of the mind. Part of the ground of this course is still intact at the rear of the new hospital.

14. Another adjunct of the health aspect occurred with the Hydropathic movement in the 1840s. Please explain. Is Culcrieff the best such example?

Culcrieff is certainly a good example but not necessarily the best. The Hydropathic movement as you rightly say was first started in the mid 1800s, with the lavish grand buildings which were initially opened as medical establishments, with a resident physician, caring for the well to do in a five star environment, spa treatments and so on. This trend changed and gradually fewer guests came as patients and more came as holidaymakers. Increasingly it was the recreational and leisure facilities that mattered, and golf courses and tennis courts became the norm for a Scottish Hydro.

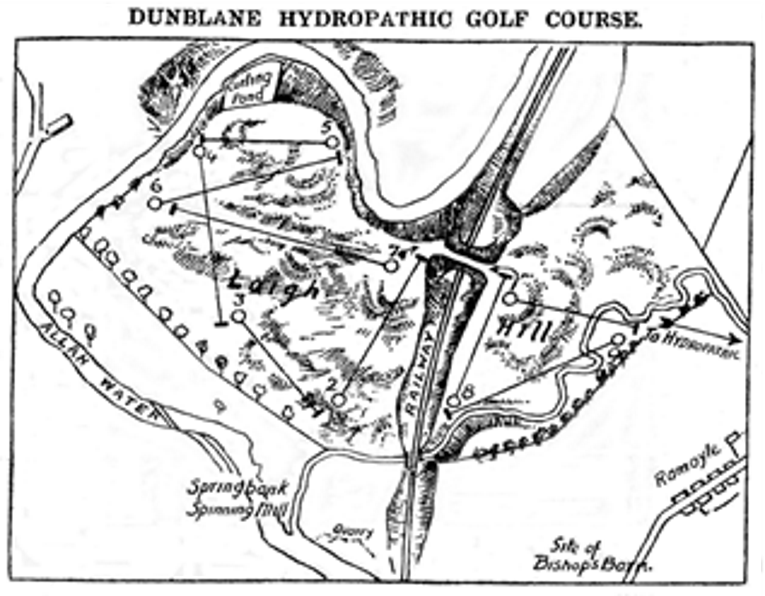

The one time treatment centres for the rich had turned into five star Hydro Hotels with a golf course to boot. It didn’t take long before the railway companies saw an opportunity and many of these fine establishments were taken over by the shareholders of the railway. The hydro’s were a sort of forerunner to Gleneagles but not quite as large. The finest of these in my opinion is the Dunblane Hydro which had a nine hole course laid out and opened by Old Tom Morris. The course was a wee cracker and is now a public park.

15. Do I take it correctly that the old Rhodes golf course is now part to some degree of the Glen Club in North Berwick? The picture you have of the Rhodes Course from 1906 makes one drool.

Absolutely spot on Ran, the original Rhodes course was much further South than the existing Glen course, and when the Glen was instituted in 1906 the two courses were basically joined together. Golf had been played at Rhodes prior to 1800.

16. Plenty of the 500 courses were built with the gutta percha in mind and therefore took considerably less space. How many hectares did a typical 9 hole course occupy back then?

This question brings back a flood of memories from our Arbory Brae golf course at Abington, as we literally weeded and trimmed the 30 acres of ground which constituted the old course. As we laid out the nine hole course almost exactly as it was in 1891 with the help of an old layout sketch, we knew the area was an accurate example of a typical nine hole course from the 1890s. Arbory Braes covered 30 acres which is about 12 hectares, and therefore an 18 hole course at the time would be ~60 acres or 24 hectares.

17. It is more than a bit sad how much more ‘chunky’ courses have become. I guess we know the answer but … what did the Haskell ball mean to these courses?

It’s pretty amazing how a wee white ball can cause so much trouble!! When the Haskell first came out in 1901 the implications were not immediate, however, with its extra distance, some courses, which couldn’t extend, because ground was not available, were in trouble. I know of at least 35 courses which closed purely because of the Haskell ball. I also know of six courses which had the idea of reducing the number of holes to 6 just to get some longer holes in play, however, they also closed, eventually. The clubs that did manage to secure extra ground for extensions still experienced major problems in negotiating new leases etc, with financial burdens placed upon the club’s funds. Progress brings its own problems, and it is still happening today.

18. Add in practice areas as demanded at resorts today and a modern course takes up ~4 to 8 times (!) more room today than a course built 120 years ago – that is not good! The quote ‘Those who don’t know history are doomed to repeat it’ springs to mind while reading your book. Based on all you research, what take-away points might you pass on to a modern developer who is considering building a course?

Wow!! Me, I’ll pass on advice or ideas, not sure I’m qualified for that, and you might not like what I suggest. Coincidentally, there is a course being constructed in Scotland at the moment at Dumbarnie links in Fife. The architect is Clive Clark, and the new course is being laid out adjacent to the old Dumbarnie links which was first instituted in 1820 with the Hercules Golf Club.

It’s absolutely fascinating to stand on the hillside of the new course, and survey the new links as it slowly comes to life, and then to turn around and look down on the old links with the ruined clubhouse in the background. It is a David and Goliath situation with David being born in 1820, and Goliath in 2020. David was approx. 28 acres for nine holes and Goliath is over 200 acres for 18 holes, so what does that tell you.

O.K., the bit you won’t like, I’m too old now and set in my ways about where the game should be going in the future, but it can’t keep getting longer and longer with modern technology dictating the game’s future.

I say, let’s get back to basics, make the courses shorter, but tighter, and let’s have the Balata ball back and teach players how to shape the ball again. The game is all about big hitters, and even the adverts are influencing us, Boom Baby Boom!!!

19. Plenty of us, especially those that walk, agree with you! To conclude, your book has 500 defunct golf courses, but as you noted above, you have additional 300+ which couldn’t fit into the initial publication. What is your intention with the remainder and how can we learn more about them?

Yes, my publisher (David Hamilton of the Partick Press) explained to me at an early stage that it was impractical to try and fit over 800 courses into one book for obvious reasons so we had to just go with the 500. If this book goes well, and I’m not referring to financial returns, but if it is received well, then we might do a second edition. The other alternative is simply to slot them into my web site: www.forgottengreens.com.

20. Do you intend to carry on with your research of ‘forgotten greens’?

As far as continuing my research is concerned, I am more enthusiastic about the project than ever! I am now semi-retired but the monster needs feeding from time to time (Money) so I won’t be able to dodge about Scotland as much as I wish. In the past two weeks I have already found another 3 courses, the final one being another private estate in Sutherland at the fairy tale castle of Dunrobin, so on it goes! Perhaps some rich American might want to sponsor me with the ongoing project?