Feature Interview with Ed Oden

June 2019

1. What prompted you to found perrymaxwellarchive.com? What do you hope to accomplish with it?

Honestly, it all started with this thread on GolfClubAtlas.com… https://golfclubatlas.com/forum/index.php/topic,49744.msg1126766.html#msg1126766. I had been intrigued by Maxwell for a while since his architectural roots were in Oklahoma, where I was born and a good chunk of my extended family still remains. I’d been living in North Carolina for over fifteen years at the time and for some unknown reason felt a pull to reconnect with my home state. So I decided to combine a trip to visit my ailing father with a tour of Maxwell courses in Oklahoma and Kansas. That week is among the most cherished memories of my life. One on one time with my Dad mixed with day trips to visit Maxwell courses.

The GCA thread was the end product of that trip. I knew that I wanted to do something more substantive than a photo tour, but had no idea exactly what I wanted to say. The initial post thankfully took me forever to write. It forced me to give meaningful thought to what I had seen and what it meant. At the time, I was not confident about my analysis. But looking back on it now with eight years of hindsight, there isn’t much I would change.

In any event, I received a lot of positive feedback from that thread and my interest in Maxwell had been peaked. So I started thinking that someone should start a Perry Maxwell society since there wasn’t one at the time. My first step was to reach out to Chris Clouser. I can say with complete confidence that the Perry Maxwell Archive would not exist if Chris had not been so gracious with his time and, more importantly, in providing me with his files on Maxwell. In truth, my vision at that point was nothing more than creating a website, which I thought would be a fun project. But I thought I needed to do a little research following up on what Chris had sent me. I will never forget the very first night I started digging in online search engines and was blown away to almost immediately find a course designed by Maxwell (Neosho Golf and Country Club in Neosho, Missouri) that hadn’t previously been mentioned by Chris, Cornish and Whitten in “The Architects of Golf” or in any of the other usual sources for golf course attribution. Within a few more days I found another and then another. I was hooked. My focus quickly changed from the creation of a society to research and the creation of a timeline of Maxwell’s life and work.

The Perry Maxwell Archive is the conduit for sharing the fruits of my research and those of others who have contributed along the way. If there is one thing I’ve learned over the last eight years, it’s that you never know the whole story and there is always something new to discover. The beauty of a website is its flexibility to evolve as more and more information becomes available, whereas a book can become outdated very quickly. The Perry Maxwell Archive is intended to be a collaborative effort. My hope is that the Perry Maxwell Archive will constantly evolve and grow as interested individuals and clubs contribute content that adds to our collective understanding of Maxwell.

2. You started collecting information in 2011 and the site went live March, 2019. Along the way, what three pieces of information did you discover that most surprised you?

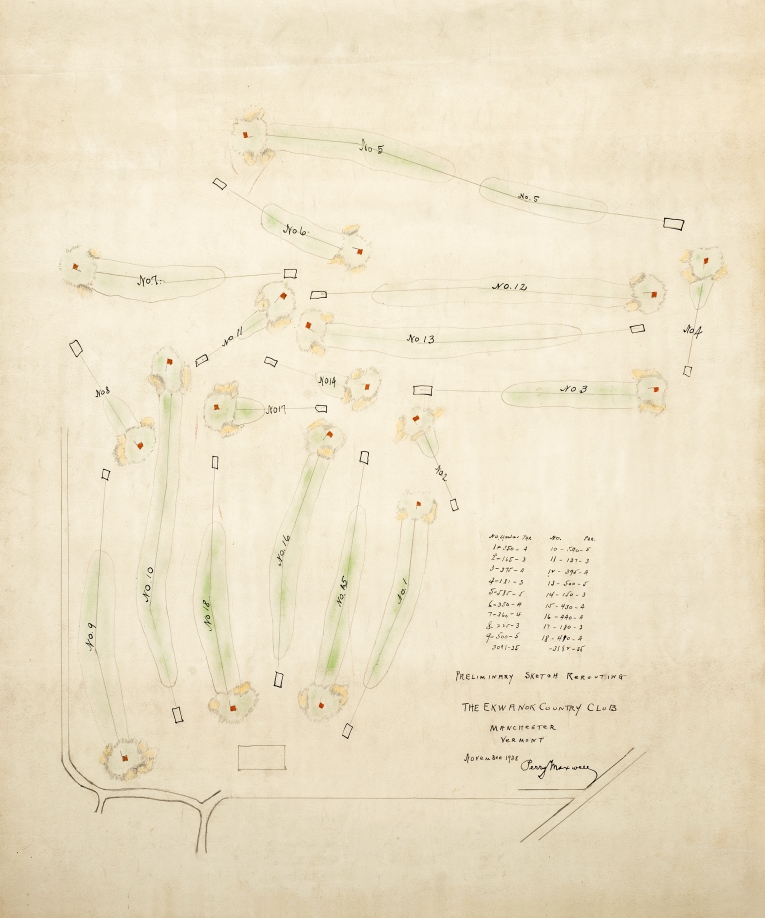

The discovery of Maxwell’s involvement at Ekwanok was undoubtedly one of the biggest highlights of my research. In 2013 I stumbled across a 1939 article that, based on the headline, was supposed to be about Prairie Dunes, but actually devoted more space to Ekwanok than anything else. According to that article, Maxwell had spent the previous week at Ekwanok “revamping some of the outmoded greens and making them blend into the landscape.” After pulling myself up off the floor, I sent the article to you and you put me in touch with Bruce Hepner, Ekwanok’s consulting architect. Bruce did some digging but didn’t turn up anything. Then a few months later I found a second article from 1940 mentioning that Maxwell had remodeled Ekwanok where the national intercollegiate golf tournament was being played. At that point I was convinced that Maxwell had in fact worked at Ekwanok since I now had two articles which essentially bookended the beginning and end of his involvement. So I decided to call the Manchester, Vermont historical society to see if they might be of help. Fortunately for me, the woman I spoke to at the historical society knew Chip Stokes, who is the current historian at Ekwanok and the son of the author of the club’s history book. I sent Chip the two articles and we spoke a couple of times. He was skeptical but promised to look into it. A year passed and I hadn’t heard anything from Chip and, frankly, assumed I likely never would. So it was a great surprise when Chip called to say that he had found Maxwell’s original November, 1938 “rerouting” plan for Ekwanok. It is a truly beautiful piece of art unlike any other routing plan I have seen of a Maxwell course. The copy I have hanging on my wall is one of my favorite possessions:

While it is clear that Ekwanok never fully implemented Maxwell’s rerouting plan, I am equally confident that he did work on the course in advance of the 1940 intercollegiate championship, most likely renovating the greens.

I also wasn’t prepared for the sheer pace at which Maxwell worked and lived. He was always on the go. Constantly traveling; at one point Maxwell estimated that he was driving 100 miles a day on average. His energy was boundless and he rarely sat idle. Maxwell wasn’t content if he wasn’t learning something new, expanding his mind, serving his community or creating something special – motivated more by a desire for personal growth than recognition.

Which leads me to the last thing that surprised me. Other than a few minor complaints about things that didn’t turn out quite as expected on specific design jobs, there are virtually no negative reports about Maxwell. No character flaws, sordid affairs, shady deals or lapses of judgment. Maxwell seems to have been almost universally respected and admired. With one glaring exception – here is the Greensboro Record’s November 25, 1940 account of a bizarre incident while Maxwell was in town working on the Gillespie Park golf course:

“A brief lecture on the respect for authority which is inculcated by military training was given in municipal-county court Monday by Judge E. Earle Rives in disposing of a case in which the defendant was charged with failing to obey a traffic officer while in the line of duty.

The defendant was Perry Maxwell, of Ardmore, Okla., who is in the city temporarily to supervise construction of the municipal golf course in Gillespie park.

Maxwell contended that the incident on East Market street, near the bus station, Sunday night was a ‘misunderstanding’ between him and the police sergeant. However, the latter testifies that the defendant continued the double-parking position of his car so long and acted himself in such a defiant manner that it was necessary for the officer to draw his gun and threaten to shoot down a tire if Maxwell allegedly started to drive off with the officer on the running board.

The defendant denied this, swearing that, contrary to the sergeant’s statement, he did not allow his machine to stand in the street after two other cars had moved. Maxwell claimed that he only followed the example set by drivers of the other two automobiles.

After hearing the conflicting statements from the witness stand, Judge Rives asked the defendant if he had ever had military training. There was a negative answer and then Judge Rives said that army training is one of the most effective agencies for instilling respect for authority.

Judge Rives continued prayer for judgment on payment of the costs.”

It doesn’t sound like Maxwell was on the Christmas card list for Greensboro law enforcement and judiciary in 1940!

3. Chris Clouser and you have done more to shine the light on Maxwell than anyone else. In reading your site and perusing the compilation of information, you are obviously extremely knowledgeable on Maxwell yet the path that you have taken is to list facts that can be supported. That is to say, you offer few opinions on the material you have gathered even though the last eight years have made you an expert. What made you select this manner of presentation?

For the most part, I think the various societies bearing the names of ODG golf course architects have been great. But I worry that they occasionally sacrifice historical accuracy for advocacy and promotion of their “guy.” I’m not interested in walking that tightrope. So it is extremely important to me that the Perry Maxwell Archive be an unbiased resource. While I certainly have my own opinions about things, to the maximum extent possible, I want the website and, in particular, the Maxwell timeline to be factually based reflections of the applicable source materials and not an interpretation of those materials. Rather, I think readers should judge merit for themselves. That’s why, wherever possible, the source materials are linked to timeline entries so that readers can view them and draw their own conclusions regarding the relevance, reliability and impact of the information provided. Clearly identified editorial notes are included in the timeline in an effort to provide additional context or information where appropriate, but otherwise I’ll save my personal opinions and interpretation for a beer at the nineteenth hole or venues like GolfClubAtlas.com.

4. You make the point early on that unlike Ross, Thomas, Tillinghast, etc., nothing exists from Maxwell in his own words on architecture. Why is that? He was a learned man, so that isn’t it. What about his correspondence to the various clubs? Where is that?!

While Maxwell never wrote a book or authored any articles on golf course design like many of his contemporaries, there are a few places where we get glimpses of his architectural philosophy. The most notable is a profile in the February, 1935 edition of The American Golfer magazine, which directly quotes Maxwell on a variety of topics:

“Leave the earth where you find it, – and the tee where it lies.”

“It is my theory that nature must precede the architect, in laying out of links. It is futile to attempt the transformation of wholly inadequate acres into an adequate course. Invariably the result is the inauguration of an earthquake. The site of a golf course should be there, not brought there. A featureless site cannot possibly be economically redeemed. Many an acre of magnificent land has been utterly destroyed by the steam shovel, throwing up its billows of earth, biting out traps and bunkers, transposing landmarks that are contemporaries of Genesis.”

“We can’t blame the engineers, surveyors, landscape experts and axmen for carrying out the design in the blueprints, most of which come into existence at the instigation of amateurs with a passion for remodeling the masterpieces of nature. A golf course that invades a hundred or more acres, and is actually visible in its garish intrusion from several points of observation, is an abhorrent spectacle. The less of man’s handiwork the better a course.”

“I have since made golf architecture my life work, having built several along the lines of Ardmore, never, at any time attempting a piece of property devoid of natural features.”

“Far too many [bunkers] exist in our land. Oakmont, Pittsburgh, where the National Open will be played this year, has two hundred. Other courses famed everywhere average one hundred and fifty. From twenty to twenty-five, plus the natural obstacles are ample for any course. Millions of dollars annually are wasted in devastating the earth; in obstructing the flow of the rainfall; in creating impossible conditions.”

“You will never see it [Dornick Hills] until you play each of its eighteen holes, for the very simple reason that it does not obtrude and is not an eyesore. Not a square foot of earth that could be left in its natural state has been removed. No pimples or hummocks of alterations falsify its beauty. There are but six artificial bunkers, the rest are natural, and all the driving tees are within a few steps of the putting greens. To date no man has played Ardmore in par, yet my daughter, still in her ‘teens, has broken 100 on it.

Terrific nuggets which only serve to whet the appetite for more. Clearly Maxwell had a way with words and was eminently capable of delivering a thoughtful treatise on golf course design. I can’t answer why he didn’t do so with any degree of certainty. Maxwell was humble and unassuming by nature and wasn’t a public self-promoter. On the other hand, he was without question a master networker who had the uncanny ability to connect with people across a seemingly endless socioeconomic spectrum – from frontier farmers to oil wildcatters, the world of high finance, Northeastern blue bloods, intellectuals and academics and a certain British doctor turned golf architect. Maxwell was equally comfortable in all settings and wildly successful at putting others at ease notwithstanding any cultural, educational, economic or social differences. My sense is that he just preferred personal interaction to mass media. Perhaps the absence of any publication on golf architecture is reflective of that tendency. If so, I am hopeful that the flip side of that same tendency is that there is still much to be learned from Maxwell’s interaction with individual clubs and courses. My focus to date has been skewed toward mining available public sources in order to get a baseline for the timeline. For the most part, information in the possession of clubs and other private sources is largely untapped. The next step is to build bridges to those private sources in an effort to add to the information and materials collected in the Perry Maxwell Archive. I would like to think that this Feature Interview is a part of that process and will help raise awareness about the Perry Maxwell Archive among clubs, their historians and other interested persons and trigger the discovery of new and additional information.

5. You write, ‘Maxwell reads “The Ideal Golf Links” by H.J. Whigham about the National Golf Links of America in the May, 1909 issue of Scribner’s Magazine.’ And a year later he goes to NGLA and meets C.B. Macdonald. Throughout the ensuing decades, he made incessant train trips to the Northeast. Is that where he learned what constituted good golf?

Maxwell’s entry into golf is so comically farfetched it’s hard to believe. His hobby at the time was tennis and his wife didn’t like the toll playing tennis in the Oklahoma summer heat took on him. She was the one who found Whigham’s article and gave it to Maxwell with the idea that golf might be a better pastime for his health. Maxwell hadn’t even seen a golf course to that point, much less played the game. His wife was actually the inspiration for thinking about whether their property in Ardmore could be adapted for golf.

Most sane people with a grain of common sense would give the idea nothing more than a passing thought before tossing it onto the scrap heap. But not Maxwell, he dives in head first with a mixture of the frontier spirit endemic to Oklahomans and the broader American conviction of the early 20th century that anything was possible. To his credit, Maxwell realized that he needed to see what was out there. After visiting as many courses as he could in the South, he then headed east and marched into the office of then USGA president Robert C. Watson. Maxwell told Watson that he was “a seeker after knowledge and would like the privilege of visiting a few of the eastern golf courses, having no social connections or acquaintances in the east.” Watson, who was a founding member at NGLA, provided Maxwell with a letter of introduction to at least a dozen of the most prominent clubs in the Northeast. This is presumably when Maxwell first met C.B. Macdonald.

Maxwell’s initial inquisitiveness was almost certainly born from a virtual vacuum of understanding of golf course design and construction. But that inquisitiveness never left him as he continued to tour courses in the U.S. and the U.K. throughout his career.

6. In 1914, ‘Maxwell goes to Wright and Ditson’s sporting goods store in Boston, where Francis Ouimet worked. Ouimet helps Maxwell buy his first set of golf clubs and they become good friends.’ What kind of a player was Maxwell, given that he didn’t have his first set of clubs until he was 35 years old? Did he play much?

Maxwell didn’t just buy one set for himself, he actually bought 10 sets and brought them back to Ardmore as enticements to get the locals to join Dornick Hills. There were only two residents that had ever played the game and Maxwell wasn’t one of them! So I think it’s safe to say that the standard of play was extremely low at the time. Everyone in Ardmore was essentially starting from scratch, including Maxwell. That being said, it appears that he picked up the game quickly (he was a decent enough athlete to figure in statewide tennis competitions) and was initially one of the better players in Ardmore. He regularly played in and occasionally won club tournaments at Dornick Hills and tied the amateur course record with a 37 in 1916. He competed in and won early round matches in both the 1917 and 1923 Oklahoma state golf championships. While I doubt Maxwell would have ever described himself as a good player, he was at least competitive within the context of play in an area new to the game of golf, particularly early on. However, it seems his frequency and level of play dropped as his architectural career took off. There are very few reports of him playing after the mid-1920s other than at grand opening ceremonies for courses he worked on.

7. Is it accurate to say that there are several references to Maxwell going to Scotland but you have only been able to corroborate that he went once? What U.K. courses do you know for sure that he saw?

That is correct. To date, the only U.K. trip that I have been able to conclusively verify was in the Fall of 1923. We know that Maxwell, along with his sister and brother-in-law, arrived in Liverpool on September 23rd and departed from Southport on October 20th. According to the September 9, 1923 Daily Oklahoman, Maxwell’s intention was “to study links and manners of the game as played by the originators of the sport.” Piecing various accounts together, it appears that, at a minimum, Maxwell went to St. Andrews, Rye and Westward Ho!, met with MacKenzie, most likely in St. Andrews, and visited his ancestral home in Anstruther, Scotland on this trip. There are also pictures of Alwoodley and North Berwick in a portfolio of photographs believed to have been taken by Maxwell on his 1923 trip, so he probably visited those courses too. In all likelihood he saw many others in the month he spent in Scotland and England, but we may never know for sure exactly which courses he toured. Perhaps interested persons in the U.K. can check their club records for evidence that Maxwell was a visitor or guest in September or October of 1923?

There is also ample evidence that Maxwell crossed the pond on other occasions as well. We just don’t know exactly when. A November 10, 1920 report in the Daily Ardmoreite suggests Maxwell might go to Edinburgh in June of 1921 as part of a delegation attending an International Rotary meeting. And the September 23, 1935 Lawrence Journal-World reported that Maxwell “has made two trips to Scotland and England.” Most compelling, the only detailed interview with Maxwell known to exist, his February, 1935 profile in The American Golfer magazine, quotes Maxwell as saying he took “Frequent trips to Scotland.” I’m hopeful that evidence will eventually be uncovered to pin down the dates of his other trips to the U.K.

8. ‘Maxwell designs Arkansas City Country Club in Arkansas City, Kansas, where he earns $500 for his first professional design fee.’ That’s after he had built Dornick Hills and Twin Hills. Press Maxwell went to Philips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts and then Dartmouth and his daughter went to Wesley. He enjoyed a comfortable life by all accounts but how did he pay for it?!

I don’t know that Maxwell was ever extremely wealthy, but he certainly did live a comfortable life. His grandfather was a Kentucky farmer and landowner. Maxwell’s father, James, was a small town doctor and his Uncle, Pressley, was a successful businessman in Paducah, in part through proceeds of the sale of the family farm. Pressley eventually invested in a Texas property that struck oil, making a small fortune that Pressley used to support the broader Maxwell family for several generations. So Maxwell had the benefit of family money to some degree.

Perhaps as important as family money, however, were family connections. Uncle Pressley was also an investor in Marion Bank in Marion, Kentucky. Maxwell had originally enrolled at the University of Kentucky before transferring to Stetson for health reasons – he had tuberculosis and the family thought a change of climate might do him well. Unfortunately, his health did not improve and, after dropping out of school and travelling in search of a place that might help assuage his health issues, Maxwell returned to Kentucky and started working at his Uncle’s bank in 1899 at the age of 20. A few years later, Pressley used some of his Texas oil money to buy an interest in Ardmore National Bank, whose president was Lee Cruce, a fellow Kentuckian and Maxwell family friend who had relocated to Ardmore in the early 1890s and would later become the second governor of the State of Oklahoma. Through his Uncle’s connections and his relationship with Cruce, Maxwell took a job at the bank upon moving his family to Ardmore in 1903.

Ardmore of the early 20th century was a mercantile hub born of cotton and oil. By all accounts, Maxwell became a successful and influential businessman in his own right, no doubt assisted by his position at the bank and proximity to Cruce. He had strong ties to the booming oil industry and was deeply involved in both the Ardmore and Oklahoma Chambers of Commerce. While family connections may have provided Maxwell with an entrée into the business world, he built a wide network of wealthy oilmen, land barons and industrialists that furthered his career as a banker and, later, as a golf course architect.

So it’s clear that Maxwell had achieved some level of wealth by the time he left the banking business. At least enough to buy several hundred acres of farmland in Ardmore for Dornick Hills and the land for Twin Hills (which he owned, designed, built and operated prior to selling in 1926), sacrifice a successful banking career to become a golf course architect despite being a single parent to young children after his first wife died, and send his kids to private schools in the Northeast. And while some of his fees may seem shockingly low by today’s standards ($500 in 1925 would be about $7,200 in 2019), unlike most of his peers, Maxwell stayed busy throughout the Depression and World War II. At the time of his death, Maxwell’s estate was valued at $750,000, which equates to more than $7,100,000 in today’s dollars.

9. You found some blockbuster quotes from the Daily Oklahoman in 1926 after Dr. Alister MacKenzie visited Twin Hills with Maxwell. MacKenzie “was favorably impressed with the Twin Hills course” and says it “would rank with those on Long Island which were built by Charles MacDonald.”One was Mackenzie declares that Twin Hills is “Better than the three American courses I have been hearing about all my life, The Links, The Lido and Garden City.” Also, “Mr. Maxwell speaks of my ability to make a good fairway or develop a worthy green, but I wish to tell you that in laying out a golf course and to give it everything that the science and art of golf demand, Mr. Maxwell is not second to anyone I know.” Wow! What did you think of Twin Hills when you saw it in 2011?

Twin Hills is one of the most underrated and under the radar courses I have seen. It is almost an afterthought in Maxwell circles, much less broader discussions about golf course architecture. But, as I mentioned in my GCA thread on Maxwell, the two courses I kept coming back to for examples of what I experienced in Maxwell’s work were Dornick Hills and Twin Hills. You can pretty much find everything you would want to know about Maxwell’s tendencies and quality golf course design at Twin Hills. Great piece of property. Terrific routing utilizing the natural features of the land. A paucity of bunkers. Fantastic greens. It’s all there, albeit sometimes hidden beneath the effects of time. I would love to see what a restoration could do for Twin Hills. I think it would be an absolute gem. For example, take a look at these images of the original bunkering at Twin Hills:

Maxwell is all too often wrongly associated with a flash-faced saucer bunker style. However, much of his bunkering, particularly in the early stages of his career, had a very natural, rough-hewn appearance. Twin Hills is a perfect example. Some who see these photos assume they reflect either MacKenzie’s handiwork or his influence on Maxwell. But Twin Hills predated MacKenzie’s first trip to the U.S. and his partnership with Maxwell by at least 2 years. I can’t rule out that MacKenzie influenced Maxwell’s bunker style during his visit to the U.K. in 1923, where the two initially met. But I think it is more likely that Maxwell was just generally captivated by the links bunkering he saw on that trip more than by MacKenzie’s work specifically. In any event, historical photos of Maxwell’s bunkering at Twin Hills and other courses dispels the commonly held view of a more modern bunker style.

10. Mohawk Park is an example whereby Maxwell had only been given credit for its greens whereby your research indicates he did the original layout. Are there other instances whereby history has shortchanged his involvement?

Absolutely, there are many. The most comprehensive previous lists of courses Maxwell designed, co-designed or remodeled are in Clouser’s book “The Midwest Associate”, “The Architects of Golf” by Cornish and Whitten and an article in the May 23, 1993 Daily Oklahoman. They are all different to some degree, but none mention the following courses where I (and others who have contributed to the Perry Maxwell Archive) have found evidence of Maxwell’s involvement:

- Platt National Park Golf Course, Sulphur, Oklahoma (1917)

- Norman Country Club, Norman, Oklahoma (1920)

- Rowanis Country Club, Gainesville, Texas (1922)

- Pauls Valley Country Club (a/k/a Hill Crest Country Club), Pauls Valley, Oklahoma (1922)

- Enid Country Club, Enid, Oklahoma (1922)

- Henryetta Country Club, Henryetta, Oklahoma (1923)

- Neosho Golf & Country Club, Neosho, Missouri (1923)

- Glenwood Golf Course, Ardmore, Oklahoma (1924)

- Hickory Hills Country Club, Springfield, Missouri (1925)

- Spavinaw Mountain Club, Spavinaw, Oklahoma (1925)

- Wilson Golf Club (a/k/a Hill Crest Country Club), Wilson, Oklahoma (1925)

- Perry Country Club, Perry, Oklahoma (1925)

- Lake View Country Club (n/k/a Rolling Hills Country Club), Paducah, Kentucky (1925)

- Noble Hills Municipal Golf Course, Paducah, Kentucky (1927)

- Jeffersonville Country Club (a/k/a Northside Country Club), Prather, Indiana (1927) – NLE

- Ponca City Country Club, Ponca City, Oklahoma (1928)

- Altus Country Club, Altus, Oklahoma (1928)

- Hillsdale Municipal Golf Course, Ardmore, Oklahoma (1928)

- Unidentified course in Corpus Christi, Texas (1930)

- Pine Crest Country Club, Longview, Texas (1931)

- Lawrence Country Club, Lawrence, Kansas (1935)

- Ekwanok Country Club, Manchester, Vermont (1938)

- Pleasant Country Club, Mt. Pleasant, Texas (1939)

- Unidentified course in Wichita, Kansas (1939)

- Corsicana Country Club, Corsicana, Texas (1941)

- Odessa Country Club, Odessa, Texas (1941)

- Lawton Country Club, Lawton, Oklahoma (1947)

- Unidentified Course in Clinton, Oklahoma (1949)

- Riverdale Country Club, Little Rock, Arkansas (1952)

- Northwood Club, Dallas, Texas (1952)

Almost certainly a handful of these clubs and courses did not follow through with their plans. And many will never be considered great by any means. Regardless, that’s almost a career’s worth of design work that was lost over time.

More prominently, I don’t believe the extent of Maxwell’s role at Augusta National is fully appreciated. He clearly touched far more of the course than most people realize. Both Ron Whitten’s work for Golf Digest and Dan Wexler’s In My Opinion piece for Golf Club Atlas have added a tremendous amount of historical detail on Augusta National to the discourse in recent years. But Maxwell’s contributions can be lost within the broader context of the overall architectural evolution of the course featured in those pieces. Many only associate Maxwell with moving the 10th green from its original location next to the MacKenzie bunker at the bottom of the valley in the existing fairway to its current location up the hill on the far side. However, he touched all but a half dozen or so holes on the course, perhaps more, and oversaw the transformation from MacKenzie’s original links-like presentation to “a more modern American conception of proper contours” (more on that later). Finally, thanks to Chris Clouser, we have a May 27, 1935 letter from Jay Monroe to Maxwell regarding the status of an “experimental bent patch” that Maxwell was working on for Augusta National. Monroe was a founding member at Augusta, one of the club’s primary financial backers, its treasurer and a confidante of Clifford Roberts. I’ll go into more detail on the bent patch below, but it is important to note here that this letter establishes that Maxwell’s connection to Augusta National appears to have begun at least by 1935, a full two years earlier than prevailing thought.

The last course I’ll mention is the University of Michigan. While MacKenzie and Maxwell are given co-design credit for Michigan, conventional wisdom seems to be that it was primarily MacKenzie with an assist from his “Midwest Associate” Maxwell. But I think there is a strong probability that those roles were actually reversed at Michigan and more like the situations at Melrose and Oklahoma City where Maxwell was given the contract and lead the design and construction of the course. Admittedly, I can’t conclusively prove that to be the case. But here is what Maxwell said in the December 5, 1934 New York Times: “I received a letter from Fielding Yost… Yost wanted a golf course for the University of Michigan. Someone took him over the Melrose course and after that he asked me to build the University of Michigan course in Ann Arbor, which I did.” Several contemporaneous reports support this interpretation with references to Maxwell having been given the contract on Michigan and in various stages of designing and building the course. Those reports were not in nationally syndicated articles, but rather locally sourced pieces in the Ardmore, Paducah, Ada and Neosho newspapers, places where Maxwell lived, worked and was connected to. I suspect they originated from Maxwell or someone very close to him, such as Dean Woods. Maxwell wasn’t one to mislead or exaggerate his accomplishments. So I believe Maxwell was probably the driving force at Michigan more so than MacKenzie.

Feature Interview with Ed Oden

pg ii

11. Maxwell is known for his greens but he was building sand greens as late as 1927. Is it accurate to say that Maxwell became an early champion of Bermuda grass and helped to spread its acceptance and use?

Yes, Maxwell was definitely an early and vocal advocate for Bermuda grass. He was part of a group of local businessmen in Ardmore championing the use of Bermuda in 1910, several years before the idea of building Dornick Hills first entered his mind. The prevailing sentiment toward Bermuda was exceedingly negative due to the difficultly in eradicating it once established. But Maxwell and his group were thinking outside the box and saw Bermuda’s invasiveness as a positive for development as an easily cultivatable high fat source of feeding cattle. They felt Bermuda grass could do for Oklahoma what blue grass had done for Kentucky. Maxwell had sodded a quarter of his farm in Ardmore with Bermuda grass. So he was clearly interested in and experimenting with grasses for other purposes long before he started designing golf courses.

When Maxwell first decided to dip his toes in the golf design water with Dornick Hills, he had no experience with golf, much less building a course and getting grass to grow. The few courses that existed in the Southwest at that time were almost exclusively constructed with sand greens. Based on his January 5, 1924 speech at the annual meeting of the USGA Green Section, Maxwell was not a fan of sand greens, inquiring of the audience whether they had “ever had the displeasure of playing sand greens.” So he reached out to the Department of Agriculture in Washington, DC to get their input on grass varieties that might work best in Oklahoma and was told that it was “a little too far south for bluegrass and a little too far north for Bermuda.” Undeterred, Maxwell visited Bermuda grass courses in Houston, New Orleans, Atlanta and Florida in 1915 and was surprised by the general lack of information and understanding with respect to the propagation and maintenance of Bermuda grass. Remember, he already had experience with Bermuda for non-golf purposes dating back at least to 1910. Maxwell understood that Bermuda was really the only grass option for Oklahoma golf at that time. And he rather quickly realized the critical role selecting the proper strain of Bermuda played in the success of establishing turf suitable for golf. As a result, he was an early and enthusiastic supporter of continuing research, particularly through the Green Section of the USGA, to identify the best strains of Bermuda grass for propagation in the South.

12. Additionally, in 1933, you note that “Maxwell introduces seaside bent grass on six greens at Dornick Hills, which is “the farthest south that seaside bent has been successfully grown” and then experiments with bent at Augusta National in 1935. Is it also fair to say that he was at the forefront of agronomy and finding grasses that were the most conducive to good golf? Where did he learn so much about turf?

That’s right. While Maxwell recognized that Bermuda grass was critical to the development of golf in the Southwest, he didn’t limit his thinking when it came to grass types. He installed bent grass greens at Neosho in 1924. Neosho is just over 100 miles Northeast of Tulsa and at roughly the same elevation, so Maxwell was working with bent in a climate that would seem to be similar to Northeastern Oklahoma at a relatively early stage of his career. He used bent grass for greens and bluegrass for fairways at Jeffersonville outside of Louisville in 1927. And Maxwell went with bent at Melrose in 1927 and Rochelle in 1930. Hillcrest in Bartlesville and Indian Hills in Tulsa switched to bent greens in 1931 and 1932, respectively, although I haven’t been able to confirm that Maxwell was in charge of those conversions. Regardless, he was certainly very familiar with bent by the time he started converting Dornick Hills to bent in 1933.

I don’t know to what degree other architects were utilizing bent in hot and humid climates at that time, but I expect Maxwell’s experience converting Bermuda grass greens to bent in Oklahoma was a driving factor in his development of “an experimental bent patch at Augusta” mentioned in Jay Monroe’s May 27, 1935 letter to Maxwell. To be fair, it is not clear whether Maxwell was officially engaged by Augusta National in connection with this work. However, given Monroe’s stature at the club and close relationship to Clifford Roberts, it would seem unlikely that Maxwell’s experimentation with bent at Augusta wasn’t sanctioned by the club even if not embodied in a formal engagement. In any event, Augusta didn’t actually convert to bent until 1981, so Maxwell’s experimentation was either unsuccessful or not implemented by the club.

13. Not many courses can claim involvement from both Maxwell and MacKenzie. And no, this isn’t where we talk about Crystal Downs. Rather I refer to Melrose CC outside of Philadelphia! Tell us about it.

Melrose has largely been forgotten as its stature has diminished over time. But it was considered a masterpiece when it opened. More importantly, I don’t think you can overstate its prominence to Maxwell’s legacy. First, it was the big break that thrust him into the national conscience. Up to that point in time, his design work had been limited to courses in Oklahoma, states touching Oklahoma (i.e., Texas, Arkansas, Kansas and Missouri), and Kentucky. Second, Melrose was the first project on which Maxwell collaborated with MacKenzie. I don’t think there is any question that Maxwell’s career as a golf course architect would have been very different without Melrose on his resume.

Maxwell had already secured the engagement for Melrose, drawn plans for the course and started construction by the time MacKenzie was retained to consult. Regardless, it was the effective commencement of their partnership. MacKenzie was justifiably recognized as one of the world’s greatest architects and his arrival at Melrose was feted in the press. But it appears that MacKenzie was used as more of a marketing tool than anything else and his contributions were limited to relatively minor suggestions and tweaks to Maxwell’s design, most notably with the placement of bunkers on the course. Maxwell was acknowledged to be the one “who really designed this layout” in a profile of Mackenzie in the March 22, 1927 Philadelphia Public Ledger. MacKenzie even wrote a letter to Maxwell effusive with praise for Maxwell’s work at Melrose:

“My dear Maxwell:

When I originally asked you to come into partnership with me, I did so because I thought your work more closely harmonized with nature than any other American Golf Course Architect. The design and construction of the Melrose Golf Course has confirmed my previous impression.

I feel that I cannot leave America without expressing my admiration for the excellence of your work and the extremely low cost compared with the results obtained. As I stated to you verbally, the work is so good that you may not get the credit you deserve.

Few if any golfers will realize that Melrose has been constructed by the hand of man and not by nature. This is the greatest tribute that can be paid to the work of a Golf Course Architect.

Yours very sincerely,

Alister MacKenzie”

Sadly, the current course bears little resemblance to what was by all accounts an elite highly regarded golf course upon opening. Construction of the Tookany Parkway resulted in the loss of substantial portions of the original course which forced a nearly total rerouting by the late 1930s. A tragic loss of the first course of the MacKenzie/Maxwell collaboration.

14. You note that ‘Maxwell is listed as a non-resident member of Pine Valley on the club’s membership roster’ in 1928 and later was made an honorary member due to his contributions there. Is there any sense of a) what influence that course exerted over him or b) he exerted on that course in addition to the original 8th green and the dual 9th green?

I am confident that the story of Maxwell and Pine Valley is incomplete. While I don’t know for sure, I suspect that he visited there during his early travels prior to building Dornick Hills. Various reports have Maxwell (i) spending “two months” in 1913 looking at layouts in a number of cities, including Philadelphia, prior to returning home to plan Dornick Hills, (ii) taking an “extended tour of eastern courses and their prized clubs” in 1914, and (iii) visiting “a dozen or more” of the most prominent courses on the east coast in 1915 via the previously mentioned letter of introduction from R.C. Watson. None of these reports were contemporaneous to the actual events, so it isn’t clear whether they are describing different trips or the dates are slightly off and they are all referencing the same one. Regardless, it seems that Maxwell had relatively unfettered access to the courses in the Northeast which were relevant to his quest for knowledge about golf course design and construction. I have a hard time believing that Pine Valley wasn’t among the places he visited. If so, think about the timing, which would have pretty much corresponded with construction and opening of the initial 11 holes of the course. Pure speculation on my part, but my guess is that Pine Valley had an early and immediate impact on Maxwell.

During the process of creating the website, I was struck for the first time by how a largely unknown banker from Oklahoma could get an invite to become a member at Pine Valley. For some reason, I just hadn’t given it much thought. My first inclination was that perhaps someone important at Melrose who was also a member at Pine Valley was impressed enough with his work to get him in at Pine Valley shortly after Melrose opened. But now I think the opposite is more likely to be true. It wouldn’t surprise me if Maxwell had already formed relationships at Pine Valley through his previous eastern tours and that those contacts opened the door for him to get the Melrose job. The most likely suspect in my opinion is Albert H. Smith, who was one of the pioneers of Philadelphia golf, the first GAP amateur champion, a founding member at Pine Valley, and a member of the “construction committee” at Melrose (Horace H. Francine, also a former Philadelphia amateur champion, William Alexander, Wayne Herkness and Charles L. Sharpless were the other committee members).

My admittedly unsubstantiated conjecture about Pine Valley’s role in securing the Melrose contract raises on interesting possibility. Since the beginning of my research, I’ve been puzzled by Maxwell’s presence in Philadelphia. He had an office there and made regular visits throughout his career. Yet Maxwell didn’t seem to do enough work there to support his investment in the area. I just assumed that I would eventually uncover additional courses he worked on in Philadelphia which would justify his regular presence. That never occurred. On the contrary, several Philly area courses previously attributed to Maxwell now do not appear to be his handiwork and have been removed from our timeline – the old Pennsylvania RR Golf Club in Llanerch and its replacement in Malvern, now known as Chester Valley (big shout out to Joe Bausch for helping unravel that mystery!), the “Ledger course” in Philadelphia (almost certainly a very poorly worded reference to Melrose which was picked up without correction in subsequent reports of Maxwell’s work), and the Eugene Grace “estate course” (in all likelihood an erroneous reference to Saucon Valley) – thereby making Maxwell’s Philadelphia portfolio even thinner than previously recognized. So what could account for so much effort in the area? My hunch is that Philadelphia and Pine Valley in particular was a fertile breeding ground for business development. During his banking career, Maxwell was far more of a relationship guy than a number cruncher. It seems only natural that he would have recognized the value in cultivating relationships in circles that generated opportunities for design work. This is what he did previously in Oklahoma through his network of oilmen and ranchers and later in his career through his ANGC connections. I’d be willing to bet that he did the same at Pine Valley in between.

As for the specifics of Maxwell’s work at Pine Valley, details are very limited. Jim Finegan’s club history and Chris Clouser’s book on Maxwell remain the best sources of information, although they don’t always jibe. According to Finegan, in 1929 Maxwell (i) brought the original left 9th green about 20′ forward and built bunkers behind it so that an overshot would not fall down the ledge into the 18th hole, and deepened and extended the bunker separating the old and new greens, (ii) removed the hump in front of the 4th green and (iii) built three bunkers to the right of 5th green to counter the steep fall off into the woods. Clouser (and Whitten) dates Maxwell’s work to 1933-35 and references changes to the 8th green at the same time as the 9th. A 1929 article in the Paducah, Kentucky newspaper indicates that Maxwell would be “remodeling several of the greens” at Pine Valley, so it is possible that he touched more than 4, 5, 8 and 9 in 1929. And a 1931 article in the Ardmore, Oklahoma newspaper mentions that Maxwell had been “given a contract to remodel the course, which could be a reference to his previous work in 1929 or an indication that he did additional work later on. Maxwell (and Dean Woods) continued to make regular visits to Philadelphia throughout the 1930s. And Maxwell’s transition from a regular member to an honorary member at Pine Valley in December of 1929 was “in recognition of his offer to respond at any time to any request of the Club for improvements or minor changes in the course without compensation.” So I think there is a strong possibility that Maxwell did more at Pine Valley than described by Finegan or Clouser.

One interesting little tidbit is that, according to Ron Whitten’s excellent chronology for Golf Digest of changes at Augusta National, Maxwell was directed to make the new 7th green “similar to the par-4 eighth as Pine Valley.” Whether that directive had its origins in suggestions from Maxwell or was independently made by Bobby Jones or Clifford Robert is unknown. Regardless, it seems Maxwell’s changes to the 8th green at Pine Valley were influential beyond Pine Valley’s gates.

15. Considering the state of the American economy and the Dust Bowl, I am in awe of his 1930s projects which included Southern Hills, Crystal Downs, Augusta National Golf Club, Prairie Dunes, Colonial, and Old Town. During that decade, what architect worked on better projects?!

I’ll tweak your timeline slightly to run from the Wall Street crash of 1929 through the end of the Great Depression in 1939. Maxwell’s portfolio during this period is astounding. His solo designs at Southern Hills, Prairie Dunes and Old Town are arguably the equal of any other architect’s over the same time frame. Add in collaborations with MacKenzie at Crystal Downs, the University of Michigan and Ohio State and with Bredemus at Colonial and I think Maxwell’s original design work is unparalleled. So it’s hard to believe that as great as Maxwell’s original designs were during this period, his renovation work may very well have been the more impressive feat. It literally reads like a who’s who of great American golf courses: Pine Valley, Augusta National, Philadelphia County Club, Gulph Mills, Ekwanok, Maidstone, NGLA, Merion, Westchester, The Links Club.

While Maxwell certainly had a number of noteworthy designs both before and after the Great Depression, his standing in the pantheon of Golden Age architects is largely based on his work from 1929-1939. Take that away and his legacy would be significantly diminished.

How Maxwell was able to prosper during this time remains a mystery. Perhaps there was less competition with the untimely passing of Raynor and MacKenzie and with Tillinghast and Ross nearing the twilight of their careers. Regardless, jobs were scarce, particularly in the Dust Bowl of Oklahoma. Maxwell actively cultivated two seemingly incongruous networks – one entrenched in oil, banking and agriculture circles of Oklahoma and its surrounding states and the other among Northeastern elites. Both continued to produce quality jobs throughout the Depression despite the difficult economic conditions. My sense is that Maxwell’s reputation for economy was an attractive selling point for hard times. His fees were reasonable and his approach inherently minimalistic. Many of his projects utilized WPA labor, which certainly helped from a cost standpoint. At the end of the day, Maxwell just seems to have been very adroit at adjusting to fit the times and, as a result, flourished.

16. Tell us about Dean Woods. Now there is a man who has never received anywhere close to enough credit!

Yes, Dean Woods is certainly underappreciated. Woods was the brother of Maxwell’s first wife, Ray. He was born in Kentucky and migrated to Ardmore in the early 1900s at roughly the same time as Maxwell and so many others from the extended Maxwell and Woods clans. Dean was a good athlete and bounced around the minor baseball leagues of Oklahoma, Texas and Arizona from the late nineteen aughts through the teens. Like most ballplayers, Woods supplemented his income with other employment, primarily as an electrical contractor. He may have also been involved in horse training since there is at least one published report of a challenge race between a horse owned by Woods and one owned by another man while in Arizona. Eventually Woods moved back to Ardmore with his wife and daughter in 1922 and settled down closer to family. His line of work in Ardmore was listed in a Rotary Club promotion in the local newspaper as “filling stations.”

The first mention I can find of Woods working on a Maxwell project was at Twin Hills in 1924. While it is possible Woods involvement in Maxwell’s work started before then, it seems that Twin Hills was the jumping off point for his role as Maxwell’s right hand man. From that point on, Woods was regularly the onsite foreman in between visits from Maxwell, often relocating his family during construction. He supervised construction at Lake View (now Rolling Hills) in Paducah in 1926, Melrose in 1927, Pine Valley’s renovation in 1929, the University of Michigan course in 1929 and Southern Hills in 1935. Frequent trips to Philadelphia suggest Woods was likely involved in most if not all of Maxwell’s projects in Philly and others in the Northeast. He led the charge at Prairie Dunes in 1936-1937 to the point where he was asked to play in the inaugural foursome on opening day. He was so instrumental in the renovation of Colonial leading up to the 1941 U.S. Open that the club presented him with a special medal of honor for his efforts.

Clearly, Woods understood what Maxwell wanted and Maxwell trusted him to deliver, which is remarkable given his lack of experience in golf course construction prior to joining Maxwell’s team. Remember, Maxwell didn’t have any training before he plunged into golf course design, so he obviously wasn’t deterred by lack of experience! In many respects Woods fulfilled a similar role as Raynor did for MacDonald, Russell did for MacKenzie in Australia, and Hatch, McGovern and Maples did for Ross. Maxwell was a hands on guy and he was regularly onsite at most if his projects. But Woods was in charge when Maxwell wasn’t around and he had complete faith in Woods’ ability to carry out his vision. Maxwell didn’t use detailed construction drawings that I know of. Rather, he did his work in the dirt. So Woods wasn’t just building to a detailed set of plans. Intuitively, that suggests that Woods was integral to the end result. Maxwell is rightfully acknowledged to be one of the greatest designer of greens the world has ever seen. But it was typically Woods who built those greens, including the famous “Maxwell rolls.” It is interesting to wonder whether those greens would have been the same if Woods hadn’t been the one bringing them to life.

Woods involvement wound down in the early-mid 1940s, not coincidentally, in my opinion, hastened by the return of Maxwell’s son, Press, from WWII. Woods ultimately retired to California and Press took over as Maxwell’s lead construction man. Dean died of a heart attack in 1950 while visiting his daughter in Ardmore.

While we’re talking about construction men, I think it is important to also acknowledge the contributions of Press. First of all, Press was an incredible man. He enlisted in the Army in 1942 and trained as a pilot. Press flew 81 combat missions in the European theater during WWII and was credited with saving the lives of 5,000 downed airmen on rescue missions in the Balkans. He was presented with the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal and was decorated with the Wings of the Yugoslav air force for his service.

On the golf side, Press worked for his father during summers while at school, before joining the construction team full time after college. After WWII, he rejoined his father, transitioned into the lead construction man as his uncle Dean moved toward retirement and, ultimately, into a co-design role late in his father’s career. Given his military background, I suspect that Press played a particularly prominent part in securing the contracts to design and build the military courses in Wyoming and Texas after WWII. Press often doesn’t get the same love as Woods does for his contributions to Maxwell’s portfolio since he didn’t play a major role in most of his father’s more critically acclaimed work. Even Press acknowledged that he didn’t have his father’s genius. Still, he went on to have a very successful career as an architect in his own right, including the second nine holes at Prairie Dunes.

17. You note that, ‘Maxwell remodels the 17th green at Augusta National and adds three bunkers at the front. Clifford Roberts was not pleased, writing to Maxwell “I do not think you should have banked up the left-hand back side of the green. This is supposed to be a run-up hole. You have changed the character of the hole by inviting players to pitch it to the green.”’My question is about Maxwell changing MacKenzie’s work – how hard/easy was it for him to do that? Mackenzie had passed away a couple of years prior so Maxwell wasn’t interfering with something that MacKenzie otherwise would have done. Still, considering how simpatico the two were in terms of design philosophies, it is interesting how many of MacKenzie’s ground game options that Maxwell got rid of (e.g. 7, 10, 17). What do you think MacKenzie would have thought of Maxwell’s work? Presumably, Jones approved of it given that it occurred, though it did start what has become a never-ending process of moving the course away from its Old Course at St. Andrews roots.

Unfortunately, we don’t know Maxwell’s thoughts regarding the alterations he made to MacKenzie’s design at Augusta. Given his reverence for Scottish links golf and his friendship for and partnership with MacKenzie, I doubt he did so lightly. What is certain is that his changes in 1937 and likely thereafter reflected a conceptual shift by the powers that be with respect to the way they wanted the course to play. Here is what the Augusta Chronicle said in January of 1938:

“A British linksland motive which was intended by the original builders of the Bobby Jones’ golf course in Augusta, has been abandoned, and the artificially thrown-up sand dune formations which were intended to give the foreign touch to a number of the greens at the home of the Master’s tournament have been replaced with a more modern American conception of proper contours to test a player’s skill.

It was a notable experiment, but an effort to duplicate the natural terrain of one country in another location, by artificial means, does not work out successfully except in Hollywood, where the camera is faster than the eye and they build the Swiss Alps and the Egyptian pyramids and get away with it.

The changes will be equally pleasing to those experts who by years of practice have perfected their strokes to the greens so they are able to hit the ball within putting distance of the pin. Because of the peculiar undulations in the approaches to a number of the original Augusta greens, many a well directed shot bounced off at a strange angle, thus discounting a player’s skill.

The greens at the fifth, seventh and seventeenth holes have been rebuilt. The abruptness of the “sand dunes” contours, which baffled the expert players has been eliminated and truly struck balls will not in the future take as many sour “kicks” as formerly.”

This is believed to be a photo of the 17th green after Maxwell added the front bunkers that Roberts objected to:

Roberts may not have liked the change, but it was clearly part of a philosophical correction. There is no way Maxwell goes down that rabbit hole on his own. At a minimum, Roberts and Jones must have been fully supportive of the directional shift. More likely, they were the ones who set it. Whether that was a wise decision is subject to debate, as is whether MacKenzie would have approved. Rightly or wrongly, it appears that the powers that be at Augusta (presumably Bobby Jones and Clifford Roberts) felt that certain aspects of MacKenzie’s original design and presentation were unnatural for Georgia and unfair for tournament golf. My guess is that they would have come to the same conclusion even if MacKenzie was still alive and objected.

18. What insight can you offer about Maxwell the man? He was in the crowd the day that Jones completed the Grand Slam at Merion. You have that ‘Maxwell attends a dinner at the Tulsa Country Club where A.W. Tillinghast is the featured speaker’ in January 1936. He simply seems indefatigable!

When I started down this path, my interest was really only in Maxwell the golf course architect. But I became fascinated by Maxwell the man as I dug deeper into his story. You are right, he had a Forrest Gump-like habit of crossing paths with important people and showing up at historic moments. As previously noted, he goes from golf neophyte to meeting the USGA president, C.B. Macdonald and Francis Ouimet in a matter of months. Still an unknown commodity, he meets up with MacKenzie on his first trip to England and Scotland, sowing the seeds of their later partnership. He played golf at Dornick Hills with President Taft; pledging to donate $10 to the Red Cross for each ball Taft could drive over a hill – Taft tried and failed. He was at Merion when Bobby Jones won the grand slam. And he was in the gallery on the 15th at Augusta when Sarazen made double eagle in 1935.

More importantly, Maxwell was deeply involved in professional, social and civic matters. He was treasurer of the Commercial Club, on the executive committee of the Oklahoma State Tennis Association, a ruling elder in the Presbyterian church, president of the Ardmore Chamber of Commerce, helped form and on the executive committee of the Oklahoma Chamber of Commerce, president and a member of the board of directors of the Oklahoma State Golf Association, on the board of the local hospital, treasurer of the county Red Cross, active in the state banking association, a member of the court of honor for the Boy Scouts, a director for various oil and gas companies, a member of the County Advisory Board, treasurer of the Ardmore Board of Education, active in the Rotary Club, chairman of the local Salvation Army, treasurer of the Ardmore Audubon Society, and a founding member of the American Society of Golf Course Architects.

If a cause needed funding, supplies or support, Maxwell was there. He made sure the Dornick Hills tractors were available to cut the grass on the local baseball fields. He was among a group of local businessmen who purchased the property for the Ardmore convention hall. He helped establish a clearing house for local banks. He was among a group of concerned citizens who successfully urged the Governor to appoint a Special Judge and impanel a grand jury to investigate the conduct of the Ardmore District Judge and Sheriff’s office and was on the committee appointed to name a new Sherriff following the criminal prosecution of his predecessor. He landscaped a new playground for the city of Ardmore. He was on the front lines in fundraising efforts for the Salvation Army, Red Cross, Tulsa University and others. He provided landscaping services to beautify the shore line and lay out park sites in connection with the construction of Lake Murray dam project near Ardmore. He planned and built a 10-acre athletic field in Ardmore for football, track, tennis and outdoors meetings. He donated chimes installed in the First Presbyterian Church of Ardmore.

Maxwell was also a big supporter of the arts and culture. He was friends with Rabindranath Tagore, a Nobel prize winning poet from India, and brought him to Ardmore to offer lectures. He advocated building a Chautauqua camp outside of Ardmore, Oklahoma in an effort to make Carter County the intellectual center of Oklahoma. He organized a radio party with the Ardmore Philharmonic club to listen to a broadcast of a concert by the Philadelphia Symphony.

Maxwell’s life was a true testament to community service and the betterment of others. According to Charles Evans, Maxwell’s longtime friend and mentor, in a tribute to Maxwell published in the Daily Oklahoman the following Maxwell’s death, “The entire home, school, church and cultural life of Ardmore, out to the very edges and on through the state and nation have been enriched for all time by the work of this man.”

19. Lastly, what three pieces of information are most tantalizing that you wish you could get sorted? For instance, you have an article that ties Maxwell to Cypress Point.

The Cypress Point mystery definitely tops the list. The materials Chris Clouser sent me (thanks again Chris!) included a copy of a letter written by Press Maxwell in 1981 listing courses that his father had worked on. Press acknowledged that he had a “lousy” memory and that the list was probably incomplete. But, while he left a lot out, everything he included checks out, except for one – Cypress Point is noted as a redesign. Initially, I discounted any involvement by Maxwell there as the product of a faulty memory and didn’t give it much thought. However, not long thereafter I acquired a copy of Frederick Baird’s 1981 history of Crystal Downs. That booklet includes a first person account by Walkley Ewing, the original developer of Crystal Downs, which describes MacKenzie’s initial visit to Crystal Downs in October 1928. According to Ewing, MacKenzie was “accompanied by his American associate, Perry Maxwell, who had worked with him on the California projects.” That peaked my interest and got me wondering if there was something to the reference to Cypress in Press’ letter after all. Then a year or so later I found a February 28, 1928 article in the Ardmore newspaper saying that Maxwell had just returned from a “business trip” to California where “he joined his partner, Dr. A. MacKenzie, one of the foremost golf course architects in the country, at Pebble Beach and together they inspected some of the most well known courses in the vicinity.” The timing fits with Ewing’s description in Crystal’s history and, more significantly, confirmed that Maxwell had in fact been in California with MacKenzie. Whether that means Maxwell assisted MacKenzie in some fashion at Cypress Point and, if so, was the redesign mentioned in Press’ letter, I can’t say. I ran all this by Sean Tully and Tommy Naccarato given their knowledge of MacKenzie’s work in California and I think there was a general skepticism (myself included) of Maxwell’s involvement at Cypress in the absence of any concrete evidence. Why would Maxwell be brought in with Hunter already there and in the fold? Still, I can’t get Press’ letter out of my mind. Maxwell clearly worked on every other course mentioned in the letter. The possibility that he may have touched Cypress is too intriguing not to continue to be on the lookout for information which might shed light on the issue one way or the other.

Another mystery which I find fascinating but doubt will ever be clarified involves Maxwell’s “dream course” described in a nationally syndicated article in May, 1941. Here is the relevant excerpt:

“Despite his pride in this Hutchinson course, Maxwell now has a dream of building the perfect course. He would construct it on the sand dunes of the New Jersey coast. He would provide an amphibious plane base so that wealthy New Yorkers could ferry down for a round of golf and return to the city within two or three hours.

The golf course architect believes that the ‘undulating’ sand dunes would make the finest topography in the world for a layout. Someday, someday, he’s going to build his greatest course there.”

Obviously, this was a dream never realized. But it seems that Maxwell knew exactly where he wanted to build it. Had he already identified specific land or only a general area? Did he intend to acquire and develop the tract on his own or were others involved? If the latter, who? And, most importantly, why didn’t it materialize? I would love to know the true story.

The last one I’ll mention I don’t ascribe much credence to, but you asked for tantalizing, so I’ll go ahead and toss it out. An October, 1963 article in the Daily Oklahoman states that, in addition to Pine Valley and Augusta National, Maxwell also remodeled “Oakmont near Pittsburgh.” I have not found any other information connecting Maxwell to Oakmont or evidence supporting this claim. And the referenced article came more than a decade after Maxwell died, so who knows where their information came from. I have my doubts about the accuracy of this article as it relates to Oakmont. But as I said earlier, there is always something new to learn. Who knows, maybe someone (perhaps someone at Oakmont) will read this interview, be inspired to do some digging and discover another piece of the Maxwell puzzle – similar to Chip Stokes stumbling onto Maxwell’s rerouting plan for Ekwanok. Now that would be great!