Feature Interview with Andrew Lewis

August, 2020

Andrew Lewis lives in Chicago, IL with his wife and six-year-old twins. During the week, he leads a team of corporate strategy, operational improvement and communications professionals for a global pharmaceutical company, and on the weekends he struggles to shoot anywhere near his 6.8 handicap index at his clubs in Chicago and/or Traverse City, MI. Andrew’s interest in golf course architecture was sparked by his time playing The Course at Yale, thanks to which he stumbled upon GolfClubAtlas.com. Andrew is the present Grounds Chair as well as Vice President of the Board of Governors at Beverly Country Club.

1. Let’s talk about Beverly’s history during the 20th century. When was the club founded and what events has it held?

Beverly Country Club has a long and proud history that extends back to its formation in 1908. Originally laid out by former club professional George O’Neil, the course hosted its first tournament of note in 1910 when the Western Open was contested and won by Chick Evans.

As a brief aside, I would note that the connection between Beverly CC and Mr. Evans extends beyond that tournament win. Many would know that in addition to his accomplishments on the course, Mr. Evans also established the Evans Scholars Foundation through the Western Golf Association, which awards full tuition and housing scholarships to deserving caddies with limited financial means. This scholarship has special meaning at Beverly CC thanks to deep involvement of many at the Club; more than a dozen current members have served as Directors of the Western Golf Association, including luminaries like Mike Keiser, Bill Shean and Bill Kingore, who is a long-serving WGA executive. To date, the Club has produced 348 Evans Scholars Alumni from the program’s total of 11,050 – the most of any club in the country and a fact of which we are especially proud.

Now, back to the tournament history.

Following Mr. Evans’ win on the original O’Neil layout, noted golf course architect Donald Ross developed a master plan that was implemented over the coming years and effectively serves as the backbone of the course as presented today.

Notable championships and champions on the “Ross course” at Beverly CC include:

- 1930 Western Amateur – John Lehman

- 1931 U.S. Amateur – Francis Ouimet

- 1937 Women’s Western Open – Helen Hicks

- 1960 Women’s Western Open – Joyce Ziske

- 1963 Western Open – Arnold Palmer

- 1965 Women’s Western Open – Susie Maxwell

- 1967 Western Open – Jack Nicklaus

- 1970 Western Open – Hugh Royer, Jr.

- 2000 Chicago Open – Luke Donald (won as amateur)

- 2009 U.S. Senior Amateur – Vinny Giles

- 2011 Western Junior – Connor Black

- 2014 Western Amateur – Beau Hossler

Looking ahead, the course at Beverly CC unfortunately is too short to host professional men’s tour events. But we certainly hope to remain relevant in the world of events and tournaments for accomplished amateurs of any age and perhaps professional seniors.

2. Describe the course as it existed on opening day in 1908.

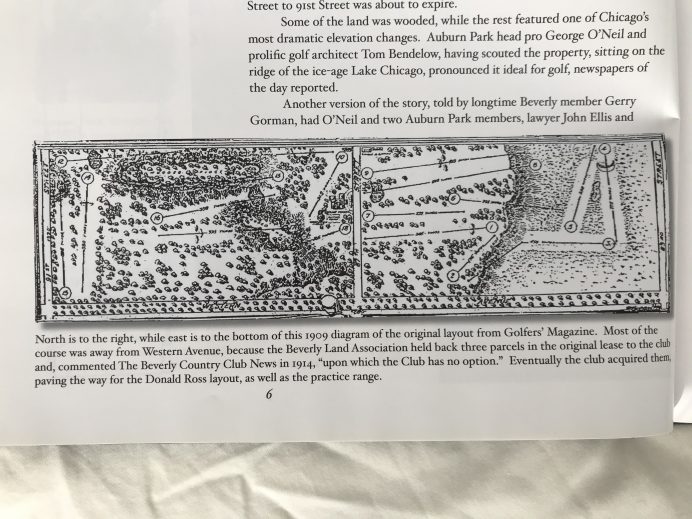

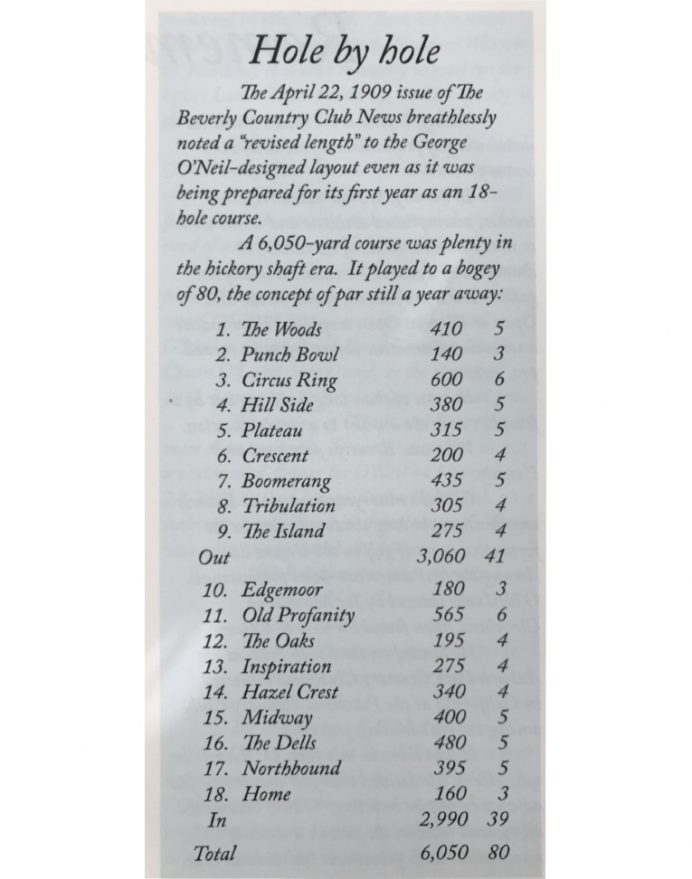

The “O’Neil course” that constituted the original layout was considered a strong test of golf that made great use of natural landforms throughout the property, most notably a ridge that cuts across what was then (and is now) the front nine. The course measured 6,050 yards with a bogey of 80, as the concept of par had not yet been widely introduced. With hickory shafted clubs and Haskell balls – not to mention holes that measured 565! and 600!! yards – this was a very long course indeed!

The original O’Neil course.

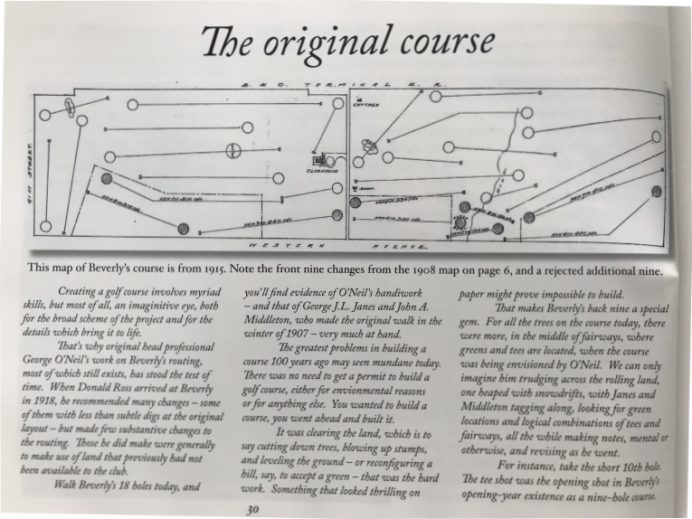

Even between 1908 and 1915 – prior to involvement from Donald Ross – the original O’Neil design at Beverly CC underwent changes.

The “Ross course” largely followed the original routing, with a few notable changes, detailed as follows. The master plan – the location of which is regrettably not known – was implemented over a series of years due to other priorities for the Club’s financial resources.

Thanks to the acquisition of additional land on the northern edge, Ross was able adjust the O’Neil routing of the front nine as follows, which allowed him to lengthen and toughen the holes and make more dramatic use of the ridge:

- Move the location of the first green further west along the ridge

- Eliminate the former second hole, a short par 3 that played back away from the ridge toward the first tee – interestingly, the mounds that surrounded the old O’Neil second green are still visible

- Shorten the former third hole (which played 600 yards!) but toughen it through bunkering and a new green

- Create new third and fourth holes – a long par 3 and a dogleg-left par 4

- Combine the former fifth and sixth holes into a single long hole (now the seventh)

- Create a new par 3 sixth hole

- Combine the former eighth and ninth holes into a single, longer hole

On the back nine, Ross left the O’Neil routing mostly intact, but did make one important change that gives Beverly CC its reputation as having a fearsome closing four holes.

The fifteenth and sixteenth holes always played as longer par 4’s, but were originally followed by another long-ish par 4 and a short-ish par 3. Ross changed that by creating the diabolical seventeenth hole – a longer par 3 that is sometimes best played by laying up short of the green – and the challenging eighteenth hole – a stout par 5 with a severely canted back-to-front green.

Newspapers that covered Mr. Ross’s visit ran headlines that read: “Ross Promises Beverly Boys a Fine Course” and “Donald Ross Gives Beverly Fine Getaway.” We couldn’t agree more.

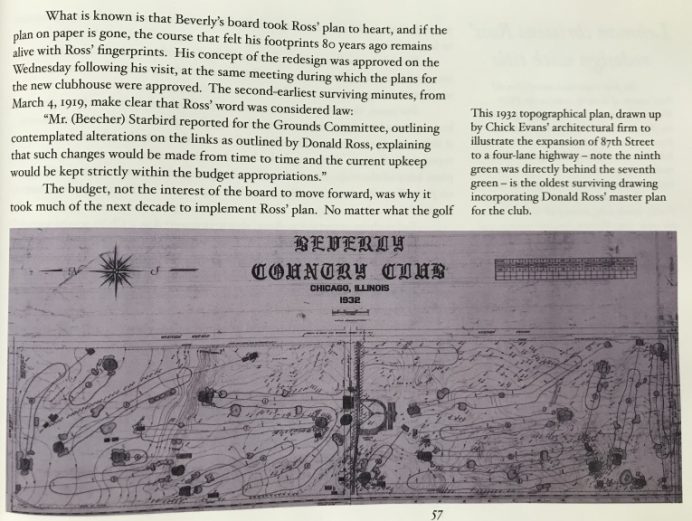

Interestingly, this 1932 topographical plan of the Ross routing was drawn up by the architectural firm of none other than Chick Evans!

3. Describe the course as it existed in 1995. What was the club’s ethos in 1995? What was its reputation regionally?

Beverly was widely respected as a difficult and attractive parkland course, probably in most Chicago golfers’ top ten in town, but there didn’t seem to be any buzz about Beverly outside of the locals.

By 1995, the course played as a boxed-in, over-treed bowling alley thanks to well-intentioned but questionably executed tree planting, especially in response to issues posed by Dutch elm disease. This made the course very hard because one could not advance the ball out of the rough toward the green on many holes, relying instead on the “Beverly Punch” – a sideways blast with a low iron just to get back into the fairway. This left players with a lot of added strokes, not that the Membership much cared about it, because it was the “toughness” of Beverly that appealed.

In terms of ethos, Beverly was a club filled with traders, lawyers, contractors, politicians and businessmen. More than half of the members lived in the Beverly neighborhood or nearby southwest suburbs. Beverly was a lively, socially active place, whether on the course, in the pool, in the dining areas or the bar. Very few had difficulty in making their F&B minimum.

4. A small cadre of members recognized something was amiss. How did they gain permission from the board to contact Ron Prichard in the late 1990’s?

There were a few members who became interested in golf course architecture, the study of which was starting to “catch on” across America at that time, and clubs that had sort of forgotten about their architectural roots to consider how they might recapture their place in that history.

In addition, “good” and “difficult” were becoming less synonymous and width, angles and the sense of defending par at the green – original principles that date back to Ross and his contemporaries – were coming back.

At Beverly CC, a small group of members led by Rick Holland, Paul Richards, Mike Floodstrand and Terry Lavin embarked upon a gradual education process, which culminated in the creation of a Restoration Committee which was composed of various factions in the club and tasked with working with Ron Prichard to consider what to do.

Not surprisingly, the Committee had great difficulty in gaining consensus. This led Mr. Prichard to suggest that he redo the “most vanilla hole,” the fourteenth, to bring his proposed plan to life. He argued that if the Club liked his work there, it would like the rest. This was a great sales job because at that time, computer renderings of bunker reconfiguration, tree removal and fairway alignment were not the type of thing one could simply whip up on an iPhone. It gave the Membership the tangible expression of potential that it needed.

But despite the overwhelming appreciation for the new 14th hole, club politics remain club politics, and continued battles over various details of the proposed restoration led to a fair amount of compromise that effectively allowed only around 70% of the recommended changes to be realized. Individual trees became sacred cows, and very few had any affection for ANY changes to hole fifteen, widely held as the best hole on the course.

In the end, the compromised restoration represented progress. Members were pleased, and the Club began receiving national attention amongst the architecture through commentary from critics like Brad Klein and Ron Whitten, and chatter on www.golfclubatlas.com and within the Donald Ross Society. But work remained.

5. What were Prichard’s first impressions?

I’m reluctant to put words in the mouth of such an accomplished craftsman and artisan – not to mention skilled player! – so I had an email conversation with Mr. Prichard to solicit his recollection.

He began by noting that Beverly is an early Ross course, and early Ross courses have certain visual and playing characteristics, many of which were absent at the time his relationship with the Club began.

He commented that the course had tree-crowded fairways but also, as a result, minimally effective fairway bunkering. There were no optional methods of play – the golfer had only to hope to hit the center of the fairway.

The bunkering at the time was in disrepair and didn’t reach close enough to the putting surfaces, although at many greens he could see that space for meaningful putting surface expansion was still available. Sand was not flashed at all in the bunkers, hence one easily could end up with a ball in the sand, “frozen” right up against the green side face.

The fairways didn’t reach the leading edge of any bunkers – in fact most fairway bunkers were outside the perimeter edges of the fairway.

Mr. Prichard closed by stating that at Beverly CC, the greatest challenge and obstacle throughout his work was resistance to proper tree removal. It took years to finally recognize that, and the truth is, that push came from a small number of committed Members. Brad Klein also deserves recognition for his effort, but it really came down to the Membership embracing the concept of removing trees.

6. Walk us through the steps required to allow Prichard to commence work. What period did Phase 1 cover? What was accomplished in Phase 1?

The major accomplishment during the work in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s was the restoration of the original Ross design intent of playing corridors that offer angles into the green.

This was guided by a thorough review of historic artifacts and photos, as well as Mr. Prichard’s extensive knowledge and scholarship on Ross courses.

Key aspects of the work included:

- Removal of many, many trees;

- Widening playing corridors;

- Reclaiming green surface;

- Shaping features (e.g., bunkers) with era-appropriate look and feel; and

- Generally regaining the scale of the property as it existed during Ross’s time.

7. What was the membership’s reaction?

Upon reopening in 2004, the Club intended to execute against the Master Plan that Mr. Prichard had developed with further ongoing tree removal, further widening of playing corridors, and restoration and/or enhancement of other features.

However, that didn’t happen. The first phase of work was viewed by some as such a success that more was not necessary, and certainly the advocates of the first phase were understandably fatigued from that effort and perhaps just wanted to enjoy the course for a while.

It all became a moot point, though, when the financial market collapse of 2008-2009 took hold. Like clubs across the country, Beverly saw its membership roster shrink and cash reserves dissipate. The Club’s Board prudently prioritized membership and financial stability and put further course restoration work on hold.

8. What period did Phase 2 cover? What was accomplished in Phase 2?

By 2013, the Club’s membership had stabilized and, what’s more, the Club’s “architectural IQ” had continued to increase. More members took an interest in what had happened before and what could happen next.

The Club invited Mr. Prichard to return and make recommendations on a staged approach to updating the Master Plan, this time supported by Tyler Rae and once again with the involvement of Brad Klein. I’d also note that our Superintendent, Kirk Spieth, has been an integral part of the team.

This led to a series of smaller projects that were executed over a few years, and which started, of course, with trees.

It was immediately clear that not only was further tree removal necessary in order to consider plans for Phase 3, but that tree removal was necessary to recapture gains made during Phase 1. Not to sound trite, but people forget that trees grow and, when left unchecked for a decade, can begin to suffocate playing corridors once again.

That is not to say that the course had re-grassed into its pre-2004 state. The work done during that time had held up nicely, and the added availability of light and air circulation had led to incremental gains in turf health every year. But more could be done.

As such, the Club embarked upon a tree management exercise the following winter and felled around 400 trees that were sick/diseased, inhibiting turf growth and health or prohibiting the appropriate expansion of playing corridors.

The Club also extended irrigation lines to stretch into the former tree line – now that the grass had access to light and air circulation, water was the missing ingredient in growing uniformly thick rough.

And finally, green surface expansion that had begun in the early 2000’s was concluded, adding some 10-15% of surface area throughout the course.

This work – which one would rightly consider catch-up work to compensate for neglect on pruning that should have been done annually over the past decade – set the stage for a full proposal to update the Master Plan.

9. That is the course that I played last fall and that is currently profiled on GolfClubAtlas. I thought it was extremely good then, one of Ross’s top dozen or so designs. How did you gain support from the members to launch into Phase 3 in 2019-2020?

As noted above, the Membership’s architectural IQ had increased substantially since 2004. More members had seen more great courses on their own and thus realized how special Beverly CC really is, and people like Paul Richards, Rick Holland and Terry Lavin had continued to beat the drum of enlightenment for the rest.

The Club could now see the scale of the land and corridors and sightlines it afforded, and acknowledged that we needed to update the scale of our hazards and features accordingly. Also, the Club realized that equipment technology gains had made the placement of certain bunkers obsolete.

The process this time followed the general template from before. We assembled a Committee to serve as a sounding board, conducted an aggressive campaign of Membership engagement and education, dispelled misconceptions and card-room rumors as quickly as possible, heavily leveraged the expertise of the Architects and our Superintendent to sell the case, and took a prudent approach to financing.

In the end, the vote came through with overwhelming support to proceed.

10. Tyler Rae drove the on the ground work – what was accomplished in Phase 3?

Tyler certainly drove the work on the ground, but it was for me fascinating to watch the interplay between Tyler and Mr. Prichard, as well as our Superintendent, Kirk Spieth. Each had a different perspective – Tyler sometimes trying to push the envelope, Kirk adding context on how Members play day to day and operational maintenance considerations, and Mr. Prichard ensuring that the work on the ground remained consistent with his overall mental vision. Very cool stuff.

I’d first note the scale and placement of hazards. With the removal of trees, we needed to restore features and hazards to an appropriate scale to fit the rest of the landscape. In some cases, such as the second hole, fairway bunkers were tripled in size. We also wanted to ensure relevance of the hazards with modern distances. The increase in scale took care of that in some instances, whereas in others we needed to relocate them.

I’d also comment on width. We widened fairways by 15+ paces in most cases in order to restore angles into the greens, which with their further expansion has enabled us to recapture many different and interesting pin positions. This allows the golfer to challenge one side (and hazard) or another in order to secure the best line of approach to a given pin.

We also introduced run-off areas on some of the greens, rebuilt the seventh in the push-up style of our other greens to ensure more consistent playability and gain pin positions (it had been reconfigured into a basic oval and built to USGA spec decades before), rebuilt the twelfth green to gain pin positions and recapture a front-left lobe visible in photos from the 1931 U.S. Amateur, and generally refurbished tee boxes and bunkers.

Finally, we re-grassed all greens with a newer turf strain to promote more consistency in all types of weather conditions and offer better resistance to disease. This was, by the way, perhaps the most greatly challenged aspect of the project. Members asked, “Our greens are perfect now; why change them?” It’s an easy comment to make in mid-September when growing conditions are ideal for bent-grass and poa, but such recency bias discounts the furry, sticky and slow conditions in the head and humidity of July.

11. The course re-opened in late May 2020. What has been the feedback thus far?

Overwhelmingly positive! After shutting down in late July 2019, we had generally wonderful weather for construction and a relatively mild winter. Grow-in went about as well as one could hope. Perhaps the greatest validation I can offer is that several of the Members who opposed the project around the time of the vote have come around to say, “I was wrong; I’m glad we did this.”

12. Please take a hole from the front nine and show us how it morphed during each stage.

The work done has brought so many dramatic and subtle improvements to so many holes that it’s very difficult to choose! I could discuss how removing trees around the first green created an infinity edge that causes doubt in many golfers’ minds. Or how repositioning bunkers on the fifth hole regained relevance with modern distances. Or how de-foresting the downhill one-shot sixth hole brought wind more into play and opened up long views across the valley below. Or how the seventh green was rebuilt to the original Ross height, footprint and push-up style so that it play similarly to the others.

That said, one hole in particular stands out as validation of the work: the par-5 second.

Designed as a mid-length par-5, the second hole features an elevated tee set back from the ridge. The tee shot plays down into the valley with offset bunkers pinching the landing area. The hole bends to the left with additional bunkers further up the fairway in the landing zone, and then bends back to the right with a long bunkered green that rises from a wide flat area in the front to a shallow shelf in the back.

A clear example of the “strategic school” of holes, the pin position can make the hole play a half-shot easier or more difficult, and the fairway bunkering clearly offers challenge when trying to gain a favorable angle for approach.

A front or middle-left pin is best approached from the right layup area in order to open a view of the pin and take left and right fronting bunkers out of play, whereas a back pin is best approached from the left layup area so as to fly up the spine of the green and avoid a right fronting bunker. A brilliant design that asks the golfer to think his way backward from green to tee in order to gain a preferred position of approach.

However, that genius had been lost over time due to the planting, growth and encroachment of trees.

In this first photo, taken prior to Mr. Prichard’s work, the most notable thing you see is what you cannot see: the green. How is the golfer to make a strategic decision on where to position his drive to optimally position his layup and open up the appropriate angle for the day’s pin? What’s more, is such play even possible in a narrow chute of fairway pinched by trees? In addition, very little in the aesthetic of the fairway bunkers would suggest that this is a Ross course.

The second hole tee shot prior to Mr. Prichard’s work.

In this second photo, taken after Mr. Prichard’s first effort in the early 200’s, you can see that the Ross nature of the bunkers has been restored. They now have a shape and feel consistent with early Ross work and, importantly, cut into the fairway. In addition, substantial tree removal has pushed the tree line back away from the fairway so as to help offer the width required for preferred angles and strategic play. However, the green still is not visible.

The second hole tee shot in 2004.

The final photo below was taken this spring after completion of this most recent round of work and although I think it speaks for itself, I’ll add some commentary.

First, note the sightlines. The golfer can see the green and fairway and thus has the ability to take various strategic decisions to work back from green to tee. It’s the highest point on the property and now offers an appropriately dramatic view.

Second, note the restored width. A small number of specimen trees remain and the tree line comes into play only on the most errant shots – although further thinning is planned on the right side of the hole. The fairway has been widened by some 20+ paces.

Third, note the restored scale. With the regained width and openness of playing corridors, it was desirable (and necessary) to enhance the scale of the features. The first left fairway bunker measured around 10 paces wide and 10 paces deep in 2004. Today, it measures around 35 paces wide and 25 paces deep! At the end of the hole, the putting surface has been extended out to the edge of the green pad – work done consistently across the course to gain 10-15% of added green surface.

Finally, note how strategic options that have. A longer hitter might try to fly the first fairway bunkers so as to reach the green in two. Those who lack such power have the ability to try to place their drives on either side of the fairway in order to open the best angle for their layup shot – which again is dictated by the pin position. And the number of pin positions has increased thanks to the larger greens.

View down the hill into the valley on the second hole in 2020.

13. Please take a hole from the back nine and show us how it morphed during each stage.

As with the front nine, there are several candidates worthy of consideration for inclusion, but for me the debate starts and ends with the twelfth hole.

Beverly CC has always had great variety in its one-shot holes, consistent with the Donald Ross principle of ensuring that each club in one’s bag saw the light of day, and the twelfth hole was always intended as a short-distance hole – somewhere around 9-iron. But over time – in large part to the Club hosting the Western Open – the length of the hole grew due to addition of a back tee box and extension of the back of the green.

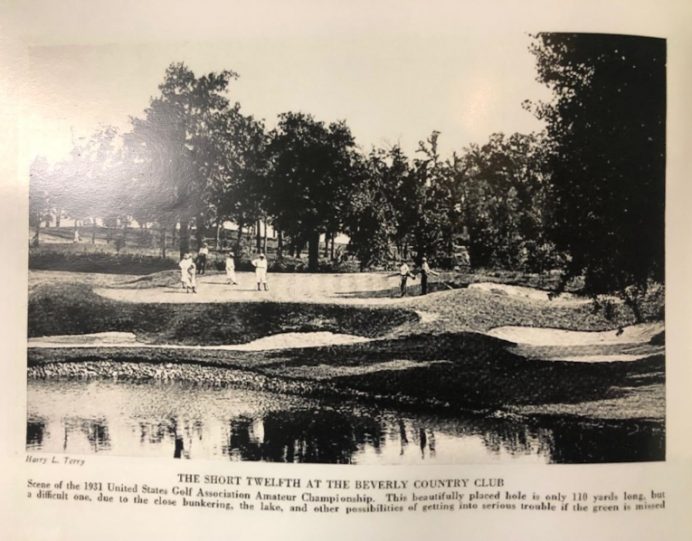

As noted before, in the latest round of work, Mr. Prichard and Tyler Rae used aerial photos from the 1930’s and press photos from the 1931 U.S. Amateur to guide their work. In the case of the twelfth hole, the main aspects of the plan were to shorten the hole to an appropriate distance and rebuild the green closer to its original dimensions.

In the first photo below, from the 1931 U.S. Amateur, a front left lobe of green that had been lost over time is clearly visible, as is a dramatic back-to-front cant. You’ll note in its caption that the hole played 110 yards at that time. Mr. Prichard and Tyler Rae sought to recapture both the lobe and cant of the green, while still accommodating the full 9-box of pin positions by creating “trout pools” within the green and softening transitions from zone to zone.

The twelfth hole during the 1931 U.S. Amateur.

The photo from the 1950’s below clearly demonstrates how the green surface had shrunk dramatically in relation to the green pads. In the next photo, taken prior to Mr. Prichard’s first round of work, you will notice that the bunker style is inconsistent with early Ross and can see a ridge running horizontally across the green that separates the original (front) area and added (back) area of the green – as well as a questionable collection of willows and other trees that are less than desirable for turf health.

The twelfth hole in 1950.

The twelfth hole prior to Mr. Prichard’s work.

The photo below was taken following Mr. Prichard’s first round of work. In it you will see that bunkers have been deepened and reshaped for consistency with Ross’s style, the most egregious willow tree has been removed, and the green surface has been pushed back toward the edge of the pad. However, the back section of green that was added circa 1980 remains. This was necessary to offer more than a couple pin positions, as the front section of the green sloped so severely back-to-front that the first third of the green was unpinnable.

The twelfth hole in 2004.

The photo below shows the finished work in 2020 – a faithful modernization of a classic and challenging short hole which, for me, ranks among the best in the Chicago area.

The twelfth hole in 2020.

Interestingly, Tyler found an important archaeological clue during the reshaping process to guide the finished product. A large tree stump was uncovered beneath the back-left portion of the existing green, confirming that the green had been extended beyond its original size. The stump belonged to a burr oak visible behind the back-left of the green in historic photographs. As a result, the team was able to more precisely align the footprint and scale of the rebuilt green with what was “on the ground” during the 1931 US Amateur.

14. How has playing the course changed this century? By that, I mean what skill sets were required to play Beverly well in 2000 and what skill sets are now required to play it effectively?

Beverly’s reputation prior to Mr. Prichard’s first round of work was as a difficult course that was very, very tight. Handicaps established at Beverly travelled well due to the potential for any hole to become a tree-driven double bogey or worse.

The role of the trees in presenting the challenge cannot be understated. One of the better players at the Club tells a great story about ending his range warm-ups with the aforementioned “Beverly Punch” – low, hooded 4-irons that fly around knee-to-waist high to escape trees – to the bemusement of his guests who had never played the course. Suffice to say, that bemusement turned to envy when confronted with the first of many instances of needing, but not having, that shot!

With the work done, I would first note that the mental and strategic aspects of the game have returned.

Through the green, the challenge has evolved from one of trying to hit laser-straight woods and irons that avoid trees into one of trying to navigate hazards in a way that confers the optimal angle into the day’s pin location. The premium on accuracy remains, but the opportunity to recover has been enhanced.

In addition, the introduction of consistently thick rough has prompted golfers to pay closer attention to lies to effectively judge club-ball-grass interaction. Shots that squirt low with a lot of run and the dreaded flier are very much in play.

This in turn feeds into the short-game demands, and many long-time Members will say that the course really shows its teeth from 75 yards and in. The greens are heavily buttressed by bunkers of considerable depth. The size, cant and internal contour of the greens challenge not only putts on the green, but pitches and chips onto the green as well. We have many new pin positions thanks to green pad reclamation and improved growing conditions. And now, with the introduction of closely-mown runoff areas around several greens, the number of options and types of shots has further increased.

I’d also comment on the variety presented. Par 3’s range in length from around 115 yards to 240 yards+. Par 4’s play uphill and downhill; straightaway and around doglegs. They measure from just over 300 yards to just shy of 500 yards. And although the par 5’s offer the hope of reachability with certain wind directions, for most players they remain testing three-shotters. True to Mr. Ross’s intent, golfers at Beverly are asked to use every club in their bags and think their way around the course.

Beverly handicaps still travel well, but this is due to the variety of challenges encountered and types of shots required to post a score – not simply tightness of the course.

In perhaps the finest testament to the work done, a longtime Member commented to me earlier this spring: “What I love about the work is that it made the course more interesting, challenging and enjoyable for every golfer – everybody from guys like him (a former mini-tour player who sports a +3 index) to guys like me (a gentleman of a more distinguished age who plays off 20), and everybody in-between.”

15. Is any work left to do?!

Thankfully, not a lot! I suppose continued vigilance when it comes to ongoing tree management is a top priority, along with the gradual introduction of fescue-type long grasses in select areas of the course. On the latter point, they will serve as a hazard in some cases and as an aesthetic backdrop in others – and I expect this to require the same type of high-tough Membership education drive as it took to gain support for re-grassing the greens.

16. What were the pros to staggering the work over a two decade period? Any cons?

In the case of Beverly CC, one major pro was the time we had to raise the architectural IQ of our Membership. It’s hard to imagine getting all the way to our current course during the late 2000’s or early 2010’s without the growth of interest in architecture among our Membership. In addition, I’d say that the multiple phases have better allowed us to adapt to changing distances in the game, especially over the past 15 years. It gave us a natural break to ensure that the course today is as relevant as it can be moving forward. And finally, it allowed us to manage the project prudently from a financial perspective. Although that’s perhaps a topic for another time, suffice to say that our Membership was pleased that our financial strength allowed us to tackle this project with minimal debt and no special assessment.

In terms of cons, I’d simply say that it’s unfortunate that those who gave life to this project won’t have as much time to enjoy the full, finished product. It took a tremendous effort to get that ball rolling, and I personally am grateful every time I play for the work done and battles fought some two decades ago.

17. Is there any advice you’d offer to other clubs considering similar projects? What have you learned that you can share?

It may sound obvious, but the first thing to do is pick up the phone and call somebody who has been through it before!

In the case of Beverly, I had the good fortune of being able to consult with former Board Members who had overseen our first round of work in the early 2000’s. The insights they shared were invaluable.

But for many Clubs, projects like this either have not occurred before, or occurred so long ago that any institutional knowledge has evaporated. That’s where networks like this site and groups like the Donald Ross Society and other similar organizations can be a tremendous help. If nothing else, you will have the opportunity to meet a number of interesting people who, in my experience, are exceedingly generous with their time – something that I’m eager to pay forward.

I’d also note that there were a striking number of parallels between this project and the type of strategic planning, organizational change and communications work that makes up a large piece of my day job. The project involved a dynamic ecosystem of individual parties whose interests and motivations were not always naturally aligned. Every Member feels that s/he is advocating in the Club’s best interest, even when views conflict from each other’s and yours. But you know what? They’re not wrong.

So at the risk of turning this into a Harvard Business School case study, I would offer four simple tips for consideration:

First, communicate clearly, effectively and frequently. Make your case for change as simple as possible. Use words AND pictures to explain what the project is intended to accomplish and why it matters – when we displayed photos of our previous mixed-strain greens with browned out poa annua next to photos of pure 007 bentgrass, the proposal to re-grass our greens became a no-brainer. Find others who can champion and extend the message. And if by the end you don’t feel like a trained parrot from the thousands of times you have had to explain the same project detail, then you probably haven’t done it right.

Second, engage and educate. Provide as many opportunities as possible for people to ask questions and raise objections so that you can address them quickly and convincingly and transparently – and, in doing so, make them vested in the process. And remember, there are no dumb questions. I recall a fellow Member questioning why we were spending so much money on what seemed to him “a couple millimeters of green surface and fairway width.” I took the time to explain how the schematics work, and that a couple millimeters on the paper plans equated to some fifteen paces on the ground – the resulting epiphany converted him into a strong advocate for the project.

Third, let the experts be experts. Although I have a keen interest in golf course architecture and have learned a decent amount about agronomy and course maintenance practices, I am neither a Golf Course Architect nor a Golf Course Superintendent. Initially, my job was to advocate for the project, to engage and educate our Members on its intent, and get their questions answered – not to design holes or draw up plans. And once approved, my job was to keep our Members connected with the project while, importantly, ensuring that our experts had freedom to operate – not to operate a bulldozer or grow grass.

And fourth, as I mentioned above, pick up the phone and call somebody who has been through it before!

18. Compare and contrast the membership of today to the one in 2000.

The composition of the Club’s Membership has changed dramatically, even since I joined in 2013.

In 2000, the Club would have been predominantly a south-side neighborhood club with a growing number of Members who lived downtown. It was multi-generational and full-service – it had a pool, tennis courts and an active social calendar.

Today, the Club is made up mainly of Members who live downtown, albeit with a still-strong contingent of those who live in the neighborhood and the bordering southern suburbs. I seem to recall you nearly falling out of your chair last fall when we decanted a bottle of Bordeaux in the men’s card room – a far cry from your experience the last time under the handling of Rick Holland, et al.!

But most strikingly, the average age and average handicap index continue to drop as the golf IQ of the Membership and quality and challenge of the course continue to rise – much credit for this goes to our current Club President, Tom Holleb.

It’s an eclectic and diverse place; Junior Golf is alive and well on Sunday afternoons, and on weekday mornings you can often see Eugene Fama – an economist from the University of Chicago (my alma mater!) and one of the Club’s three Nobel Laureates – briskly walking the course.

19. Congratulations, has the future of Beverly ever been more secure?

The Beverly Country Club today is in a great place. The Membership roster is full with a diverse and welcoming mix of avid golfers of all ages. There is a great sense of and connection to the Club’s history thanks to our older Members who remain actively involved, balanced by the constant influx of younger Members who are just setting out on their journeys. In short, I feel that we are doing admirably at living up to the vision that a prior Board set – of being a top-class family-friendly golf club with a great proximity to downtown.

Sunrise looking north over the back nine toward downtown Chicago (Credit: Andy Johnson / The Fried Egg).