Feature Interview

with

Samuel Ingwersen, AIA

November, 2017

Part Three

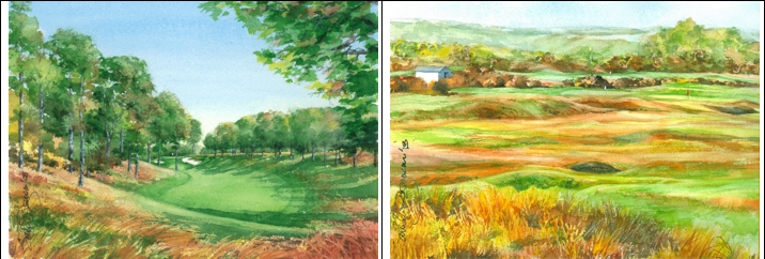

WATERCOLOR PAINTINGS of BEAUTIFUL GOLF COURSES and

The Influence of Landscape Effect Upon the Future of Golf

Samuel Ingwersen, AIA, Artist/Author, Michael Hurdzan, PhD, ASGCA, Contributing Author

What took you down the path that ultimately led you to conclude that the landscape effect had corrupted the game?

Thanks Ran, the two subjects, landscape effect and its influence upon the game of golf, are the foundation of the book’s thesis: “The beauty of golf course landscape effect is corrupting the game.”

What makes your question difficult is that there is no precedent in literature that addresses these subjects and their correlations. Many have written about the on-site beauty of a hole, strategy and design, difficulties, fairness of play and hazards but none have identified landscape effect and its impact upon the range of human experiences, from optimal joy, boredom, and anxiety to frustration that may be experienced in play of the game of golf.

What drew me on the path toward my conclusion was my quest to determine that Hawtree’s idea, “landscape effect,” had validity. Landscape effect is defined as a golf course landscape component or a composition of components designed or contrived for their look. Is landscape effect an illusion or is it real? To that end, my answer to your question goes into a great detail of historical background about the aesthetic and cultural forces that brought about and encouraged creative, unique and individualistic works of golf course architectural landscape design. As we shall see, these aesthetic and cultural forces have been largely responsible for today’s present state of golf course design ideology.

My conclusion was not yet whole until I looked deeper into a subject unknown to golf, namely the theory of games. My conclusion became clear after I found correlations to the game of golf in the works of social scientists Roger Caillois, sociologist, in the areas of game categories, qualities of games and why they become popular or corrupted and Mike Csikszentmihalyi and Susan Jackson, psychologists, whose works were in the areas of game experiences of state of flow and challenge/skill balance.

These scientists are recognized world-wide for their contributions to games and leisure theory. A big part of life is enjoyment of recreations and games and the things that make people feel good in these pursuits. Their work explains why people are attracted to games, enjoy them and have fun. A variation of their Experience Sampling Methods (ESM) has the ability to quantify and measure the human experiences in play of the game of golf. Within the framework of an ESM, landscape effects may be compared to designs of course components that may make it more likely for enjoyment and fun to occur and less likely for anxiety and frustration to occur in play of the game.

Let’s relate your premise to the evolution of golf course architecture.

We should keep in mind that the art of golf course architecture is barely 100 years old. As an emerging formative art of the Victorian Era (1837-1901), guided by a mixture of ideas of the decorative, fine and applied arts, orchestrated by aesthetes and driven by artisans and emerging designers that plied them in making the market, the new art of building golf courses would find its identity. Not surprisingly, the men in addition to their architectural talents, that most influenced, wrote and published material about the developing new art were artists. These men were Hutchinson, trained in the arts and sculpture and a member of the progressive artists group the PreRaphaelite Brotherhood; Simpson, an artist with noteworthy exhibits of his art work exhibited in London, H.N. Wethered, a professional artist and author and MacKenzie, an author, trained in the art of landscape camouflage.

Hawtree discovered the phenomena of contrived aesthetic landscape effects of course design but drew no conclusions. The idea that landscape effect had validity eventually became apparent and that subjective, human experiences subject to influences of landscape effect upon the game of golf could be quantified and measured by a golf orientated ESM. Useful information would require an ESM that would generate big data. The golf ESM would take into account many variables; course structure, golfers’ experiences and time spent on activities across various skill levels of players.

After extensive research into these two unfamiliar subjects of landscape effect and games, my premise became evident. I was convinced that my insight into probably the most serious problem in golf’s 500 years of existence, the cause of the game’s decline, should be expressed in the most able of terms. The authors determined that the most positive way to capture readers’ interests in a rather uninspiring but crucial subject, the future of the game, was enjoyment of 150 interesting watercolor paintings of beautiful golf courses with provocative narratives and research supporting the book’s conclusions.

Talk about the Victorian era in England and what shaped tastes then.

Artistic ideas come from nature and the works of others. The works of others may be objects of art or philosophical dissertations. The 18th century German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), considered by some to be the greatest philosopher since the Greeks, has dominated philosophy for the last several centuries including philosophy of aesthetics. Kant’s theories were embraced by contemporary aestheticians, artists and philosophers of the Victorian Era which exerted a consistent influence over much of the thinking within the various movements and styles of the Victorian Era. This included the Pre Raphaelite Brotherhood and the Arts and Crafts movements. Kant’s theory of aesthetics in general is that a work of fine art is unique (different, like no other), representative of no law (proportions, scale, light and color differentiations, etc.), formula or precedent, only the artists’ genius and his individuality. (20)

The new concept of genius, put forth by Kant’s Critique of Judgment, 1790 would have a profound effect upon attitudes toward ornament. The widely accepted Kantian theory compelled artistic individuality. Genius as used by Kant and other theorists meant “natural endowment,” not today’s common usage connoting superior special skills. A contemporary example of Kant’s affirmation of genius is in the bunker banks at Calusa Pines, Fl. The bunkers have sand flashes up to 20 foot high because of the designer’s compulsion to create something special and be different. The designer exclaimed of his bunker design: “Sometimes, to create something special you must take a chance and be different. (21)

The most convincing material that gives validity to Hawtree’s idea, “landscape effect,” is the genesis of its idea, the original thinking and the concept behind the idea. An artist’s achievements would evolve from the artist’s individually endowed spirit; their genius. For the first time in the history of Western art, genius had become the quintessential characteristic of the artist. And originality was its most important characteristic. The artist’s genius, “propelled their freedom of artistic self-expression from worldly constraints of conformance to religious, state and noblemen clients dictates, into a realm of intellect from which they were to instruct–rather than pander to conventional taste.” (22) As golf course design evolved from a craft to a profession, ornamental landscape effects consisting of pleasing forms and variety of compositions of landscape components would soon be manifest in golf course landscapes. And the race was on by designers to express their genius while establishing their reputations and meeting the imperatives of society’s ideas of pleasant scenery and beauty.

The philosophical and aesthetic ideas that were getting a great deal of play in Victorian England particularly in the latter years of that era were a driving force that helped shape artists’ motivations in all the various arts which by the early 20th century included course designers’ ideas of course landscape scenery. In addition to the aforementioned philosophical and aesthetic ideas were the influences of three major British cultural interests that would contribute to the ideas of beauty and variety of course landscapes. These were: 1) The world leading art of British landscape gardening, 2) the National Arts movement to improve the nation’s aesthetic tastes and 3) the beginning of the art of golf course architecture, first referred to as “linkscape gardening” and the scenic movement of 1890 started by Horace Hutchinson, author and golf’s most prominent course design theorist, to improve the scenery of golf courses.

Those are three really interesting points to drill down on, so let’s! First, British landscape gardening.

From our modern perspective it may be difficult to comprehend how British landscape gardening and the National arts movement of the 19th century would influence golf course design philosophy and construction in the 20th century. Origin of many course landscape ideas accrued from several centuries of British experiences in aesthetics, science and the art of landscape gardening. The established art of landscape gardening would facilitate solutions to both scenic and scientific problems that dealt with soils, grass, plantings and landscape needs of golf courses. The artistic touch was promoted by aesthetes like Hutchinson. Although he encouraged adaptations of advanced landscape technology applied to course design he was also ever mindful of the importance of including aesthetics; he wrote: “…as we become more scientific we may fall into a worse pit of becoming altogether undramatic … but unless that dramatic interest is kept before the eye of the linkscape gardener he may turn out a good, but deadly dull job.” (23)

The art of landscape gardening in England was the Western world’s leader in landscape gardening during the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries. By the 1900s the art was readily serving the needs of golf courses experiencing explosive growth in the latter decades of the 19th century in Great Britain. Almost every inland community was building a course, many of which were criticized by writers, esthetes and elite designers as dismal and dull, representative of the “Dark Ages” of golf in Great Britain. The art of landscape gardening was a source of national pride. It also served as an inspiration to artistic minded commentators such as Hutchinson, Tom Simpson and H. N. Wethered who would write: “There is the artistic side. No reason exists why a golf course should not decorate a landscape rather than disfigure it.” (24)

The Sutton and Carter companies were English seed merchants, supplying demand for grass seed and assisting in building courses for UK and US golf clubs well into the first several decades of the 20th century. Not only were their grass seeds sought, but also their expertise on all subjects related to grass which consisted of soil, drainage, grass slopes, preparatory work, weed seeds in soil, enriching the soil, surface preparation, selection of seeds, sowing, bird scares, worm casts, watering, mowing, rolling, destruction of weeds, top dressing, moss, fungoid diseases and even construction plans for putting greens.

An outstanding representation of landscape gardening of its time was depicted in the book The Art of Landscape Gardening (1797) by Humphry Repton (1752-1818). The book discussed the visual pleasures (the term pleasure is synonymous with sense of beauty) that could be experienced or denied by the positioning of landscape elements or components in delightful compositions. This included water bodies, building or removing hills and land forms or groups of trees that either hid or exposed a contained or borrowed scene. Other subjects included mythological structures and hydraulics. Repton persistently implored his clients he would double their pleasure if they permitted him to include a reflective water pool or pond in his landscape designs.

Humphrey Repton’s work would contribute to philosophy of course design. C. B. Macdonald (1856-1939) advised: “every aspirant who wishes to excel in golf architecture should learn by heart and absorb the spirit of … quotations from the landscape book by Humphry Repton; The Art of Landscape Architecture” [sic]. (25) Macdonald substituted the word “Architecture” for “Gardening” in his incorrect referrence of Repton’s book ostensibly to make Repton relevant to ideas of 20th century course design. The large body of knowledge of English landscape gardening arts and sciences and the work of English nurserymen would benefit golf courses. As it would so happen, American course designers would eventually make a few peculiar adaptations of their own.

Second, The National Arts Movement.

Great Britain was one of the major leaders of the Industrial Revolution. However, advanced as the country was in the manufacturing arts, many critical observers were concerned about the British people’s lagging sense of taste when it came to design of their industrial products. An exception of course was advancements in landscape gardening design. Prince Albert (1819-1861), Queen Victoria’s (1819-1901) Consort was the benefactor of the Great Exhibition of 1851. Its centerpiece, the Crystal Palace designed by a landscape gardener, is shown below.

Although The Exhibition was a success much of the English displays of goods were criticized for their inferior taste in design compared to other countries. One English critic stated: “Although the objective was to advance our national taste… Nothing was comparable to British hardware or gratings … There was, however a decided inferiority in national taste when it came to ornamental design; the way in which these useful, well-crafted objects were made beautiful through decoration.” (26) The superior, more graceful and elegant products of competing nations that were on display concerned the country’s leaders.

Ironically, The Great Exhibition of 1851 and the reactions of critics would provide long lasting benefits to the country’s sense of aesthetics and art appreciation. Soon thereafter Parliament established laws for the Provincial Schools of Art. By 1864 there were 70,000 poor (children of the working class) being educated in the “principles of art to improve the nation’s sense of taste and to better compete in international markets for sale of products…” (27) Tens of thousands of more art scholars would follow.

The most significant aspect of the National Arts Movement relative to golf was that within the next several decades a burgeoning group of art scholars and mature graduates of the Provincial Schools of Art, would become supporters for improvement of the looks of inartistic inland courses. If not pliant supporters, at least they did not oppose the ideas of scenic beauty as suggested by golf critics and commentators like Hutchinson, Simpson, Colt, MacKenzie and Wethered. By the early 1900’s the scenic course movement would advance without benefit of debate or constructive criticism. The aesthetic consciousness of the nation had been raised. There were apparently no opponents to the pleasing scenic movement or advanced thinking of the turn it would take with its future form of beauty.

And your third point, the Emerging Art of Linkscape Gardening and the Scenic Movement.

We have touched upon the arts, artists, and the influence of Kantian theory embraced by artists during the Victorian Era. These interests were a precursor to what was taking place in the new art looking for an identity. The term “linkscape gardening” conjures thoughts of beautifully landscaped golf courses. The term and the idea behind it was conceived by the same man most responsible for the golf course scenic movement. Inexorably, Kant’s philosophy (unique, like no other, different, individualistic, genius) about artists roles in creative aesthetic endeavors would become embodied in the future creative, artistic and aesthetic expressions of golf course architecture.

In the year 1890 Horace Hutchinson, (1859-1932) champion golfer, influential author and designer, the world’s preeminent golf architectural theorist would write: “Scenery is not of course, golf; but golf is a pleasanter recreation when played in the midst of pleasant scenery,” (28) an idea that would soon revolutionize golf.

After the turn of the century Hutchinson was writing, extoling the virtues of pleasant scenery but lamenting the shortcomings of “…linkscape (sic) gardeners who lacked an artistic eye in pursuing their new craft of links gardening.” (29) The pursuit to improve scenery of the course gained remarkable support in the beginning decades of the 20th century. The most notable English magazines and newspapers that covered the subject of course design, Country Life, The London Times and Golf Illustrated were the leaders. They employed the best writers, who in turn invited leading course designers to contribute articles on new design ideas. Hutchinson and Country Life provided forums within which they would commend the new work, courses and ideas of the guest contributors, supplying praise and criticism from time to time.

Hutchinson’s idea of pleasant scenery, in his 1906 book, was complemented by two famous course designers, Herbert Fowler and James Braid who took to his ideas. They contributed aesthetic experiences to his golf book related to their experiences with bunkers at Walton Heath. They stated that the looks of symmetrically placed greenside bunkers could be improved by devising alterations. Fowler said of their visual aspects: “…it does not “look” so formal if one bunker is some little distance in front of the green, and another starts ….” Braid made the following statement: “…raise bunker banks to make them “look” as natural as possible.” Hawtree concluded: “Landscape effect has crept into the (designer’s) vocabulary for the first time.” (30) Hawtree’s insight into landscape effect and its contrived use to achieve pleasant looks of course design was prescient of something amiss, but exactly what it meant for the game and golf’s future was only a guess.

Hutchinson trained for the bar and later studied in London to be a sculptor and an artist. While in pursuit of his artistic interests, he became influenced by the original Pre Raphaelite Brotherhood, (PRB), founded 1848, and its second generation movement and their principals of art. The most famous art critic, author, and lecturer of the Victorian Era, John Ruskin, (1819-1900), was also involved with the PRB and actively supported the second generation PRB artists with his influential writings and lectures. In his book, Seven Lamps of Architecture 1849, Ruskin declared that the aesthetic was the overriding significance: “A building is not truly a work of architecture… unless it is in some way adorned.” Hutchinson’s ideas of enjoyment of scenic, artistic adornment of a golf course neatly conformed to his early PRB art instruction and the influential Ruskin’s architectural adornment principals.

The prospect of undramatic course scenery by linkscape gardeners without an artistic eye, as lamented by Hutchinson, would soon be allayed, resulting in courses with pleasant scenery. An account of British cultural pride in Britain’s art of landscape gardening (even the most modest of cottages throughout all of England cultivated dooryard gardens) and the National Art Movement gives one a good understanding of the immensity of these cultural forces and how they conditioned every community’s pliant support of golf’s scenic beautification movement. It is easy to speculate, that if there had been one dissenting critique (Thomas MacWood’s comment) of the scenic movement perhaps golf’s present preoccupation with the look and its attendant problems of decline as a player participant game would have taken a different turn.

Other writers, designers and critics would become involved in the same mission as Hutchinson. The artist and author H. N. Wethered and the artist, author, and course designer Tom Simpson would write in their book The Architectural Side of Golf 1929: “For the first time, at the start of the 20th century, golf architecture … was recognized as belonging to the art of the game … In a sense it represented a revolt against a style of course construction that was unimaginative and untrue to tradition, characterized by a fondness for gun-platform tees, monotonous cross-bunkering and inartistic hazards (rifle butts as sand bunkers)—a kind of design for which the brothers Dunn (Tom 1849-1902, Willie 1869-1952) and Old Tom Morris of St. Andrews were mainly responsible.” (31)

For the next 100 years, consistently as years passed, the philosophical statements about purpose of design and the looks of a course by scores of designers and writers from Darwin in 1909 to Doak in 2010 began to change. The emphasis of beauty implacably shifted from beauty of the game to beauty of the course. “The look” of scenery that Hutchinson declared as not golf, had become golf

Architects, landscape architects and artisans have adorned their products from the beginning of time in order to achieve pleasing looks. This is no different from golf courses today that are adorned with ornamental landscape effects. The argument that an ornamental landscape effect is justified for strategic purposes does not hold water when it is outside the boundaries of possible “state of flow” and challenge/skill balances. It then becomes an obstacle to enjoyment by 95% of golfers.

Art historian Brent Brolin observed: “…ornament has been part of virtually all cultures gracing almost every appurtenance of life … Perhaps ornament has been such a consistent part of human history because it has satisfied a need for beauty that all people share. With rare exception, when ornament could be used it was, and in most cases, in proportion to wealth.” (32)

The foregoing explains how the fatal beauty of landscape effect has innocently evolved to become a driving force in golf course design.

Who are some of your favorite ‘voices’ back in the day that helped to alter/elevate golf course architecture?

The answer to this question depends upon where your interests lie. On the one hand are the players, especially that group of 95% of all players that cannot break 80. On the other hand are the non-players associated with the game whose interests and motivations are different than the players. Thus the two groups have different levels of appreciation for golf course architecture.

My interest is with the players, therefore my favorite voices, although small in numbers, from back in the formative days that have brought a certain awareness to course design today are men such as Bernard Darwin, Tom Morris, C.B. Macdonald, Walter Travis and Alister MacKenzie. They spoke about the mental and emotional attractions and beauties of the game, not of memorable visual experiences of beautiful course scenery. There is one exception, Tom Morris had no voice however there is an eloquence to the fact that of the 500 members of the Old Course of which only a handful could break 100, Tom in his several decades of stewardship was able to keep his members happy. His practical design ideas are worth listening to.

Also F.W. Hawtree, a lonely voice, spoke of the use of landscape effects in pursuit of beautiful scenery. He would later write; “Golf course architecture has become an exercise in pure landscaping.” (33) Hawtree’s statement would brand him as a heretic today if it were not for the fact that the typical landscaping costs for state-of-the-art golf courses in the USA had, on average, from the 1960’s into the 1990’s increased in cost from $7,500 to $1,050,000 per course. (34)

There were other voices, dominant, popular, voices imbued with the great message of the beautiful scenic movement, but they were leading course design in a dubious direction. Tom Simpson, one of England’s notable course designers, artist, and author was the most caustic in his criticism of dismal course design. He christened the years from 1885 to 1900 the Dark Ages of Golf Architecture: “Most of their courses would best be termed dismal.” (35) In a collaborative book co-authored by Joyce and Roger Wethered, Darwin, and Hutchinson, Simpson described the work of the Dark Ages designers “so deplorable and misguided that, so far as the golf architect and the client were concerned, it was a case of the blind leading the blind.” MacKenzie also remarked: “The beauty of golf courses in the past has suffered from the creations of ugly and unimaginative design.” (36) Hutchinson, Simpson, Wethered, Colt, Hunter, and their followers, some less indulgent and some more, appeared to ignore any benefits of all the trial and error work that had preceded their stance only to be seduced by Dame Beauty.

Having read your book, monochromatic green grass seems almost abhorrent to your eye. Please articulate why.

I have no abhorrent, as the term means, detestable thought or feeling toward monochromatic green grass in fairways and rough. But what I do have is delight in variegated colors of grasses that are mixtures of green, chartreuse, tan and yellow that turn to golds, browns, reds and pinks depending upon the light, moisture and seasons of the year. These matters of grasses set clubs apart and indicate degrees of competency of maintenance practices but most of all reflect upon a club’s leadership. If multi-color fairways cannot be sold to members today, at least, replacement of lush green roughs can, otherwise if not, it is a sorry state of management only to be looked upon with pity.

For starters related to the idea of optimal performance of maintenance and play, I quote Green is Not Great, Golf is Played on Grass Not Color, an article written by Alexander M. Radko, former National Director of the USGA Green Section; Golf Journal, Aug, 1977. Radko made a case for sensible use of water and management of grasses with improved performance. “Lush green color turfgrass means undesirable, soft succulent, out of condition, filled with juice or liquid … which often results from the needless race for color despite the fact that color has minimal effect on turfgrass quality for golf … off color grasses hold the ball nicely for fairway play.”

George Peper and Malcolm Campbell, past editors of golf magazines, co-authors of the book Links 2010, foresee crisis in maintaining green courses that threaten the future of the game. They wrote: “The days of consuming millions of gallons of water and vast amounts of chemicals to keep modern-style courses alive and green are coming to an end. In fact, the game will teeter into crisis if it fails to adjust.”

I have had an unpleasant upbringing in experiences with lush green roughs. My former club renovated the course including roughs. Irrigation lines were installed in roughs on each side of the fairway. Although beautiful, it was hard to find a ball, hard to play out of and hardly any fun. The lush green roughs added more than 40 minutes to each round every Saturday and Sunday. I believe that my experiences are so stated that I give the impression that monochromatic green is closer to dislike. I am opposed to decadent, lush green grass for the following basic reasoning and principals: Wastefulness of resources, unnecessary excessive costs, frustrating, time consuming and unaesthetic.

What do you prefer instead?

What I prefer to see instead of lush green grass in fairways and margins are improvements in the way of mixed colors in grasses that promise future benefits for golf and American golf courses, particularly playability, costs and use of less water, chemicals, fertilizers and other resources while reducing obstacles to the game.

As for aesthetics, color is the most dominant feature of artistic expression, more dominant than line or form. When J.M.W. Turner, the great English watercolorist was asked about art, he replied: “color is absolute.” As an artist, I have been fascinated with the idea, by appearances of courses from around the world, that the fairway and its margins possess the capability to provide all the adornment necessary to achieve pleasant scenery or a beautiful course while satisfying players and non-players innate desire for beauty.

Surely there are a few individuals in each golf club that see the minimal benefits with the obsession of pure green fairway and margin grass and would like their club to do something about it. Grass fairways and margins are the places to seamlessly initiate positive change.

I would like to see some of the highly visible TV featured courses develop fairway colors mixed with green. Change may arrive sooner than expected as the engine that drives taste is powered by economics. The conventional color green will then be considered for what it is: Only a color.

Examples of improvements that are proposed for Columbus CC (CCC) hole nos.5, 6, and 7 fairways and margins are shown below. Other areas are also planned. The proposed changes include elimination of lush green margin (rough) grass with replacement of a mixture of native species of sedges, fescues and little blue stem or similar. Acres of foliage and hundreds of trees have been removed to encourage more natural grasses. But these areas will still need weed control and occasional mowing in the fall to keep them thin. Thoughtful redesign will improve the challenge/skill balance opportunities for 95% of players as well as improve time to play the course and more fun for all skill levels.

Alexander Radko’s research, environmental scientists’ and the golf industry’s crisis warnings all speak to the subject of more thoughtful use of grasses, irrespective of conventional color taste, that promise benefits for the future of the game. The group scene of holes nos. 5, 6, & 7 Columbus CC, Cols, OH depicted after renovations, show tan, rust, reddish brown, green and yellow areas in fairways and margins. A photograph of the same group of holes but of a smaller scale, with lush green grasses is shown below together with other courses of different color grasses. These examples of fairways and margins are from various states in the US and Scotland.

Ohio. Fairway/margin colors: holes Nos. 5,6 &7: Green Oregon. Fairway colors: Tan, gold, brown, yellow, green

New York. Rough/margin colors: Tan, beige, rust, yellow Scotland. Fairway/margin colors: Tan, gold, yellow, green

The three small sketches, compared to the monochromatic green photograph of Ohio, holes #5,6 &7 are a much more delightful mix of colors tan, rust, reddish brown, green and yellow areas in fairways and margins. They are not offensive; in fact, they are attractive. Pinks and deeper scarlet colors are especially attractive of fescue grass when it turns to seed and the scene is backlit.

Since the development of the art of golf course architecture in America, aesthetic refinements of grass have involved its color green. Grass has many colors but the predominant choice today is the classicized color green of which now has become conventionalized. If tan or yellow colors appears in a fairway, it would be called a blemish. Choice of unblemished green as the only color for grass is a matter of convention influenced by taste.

The matter of taste is well put by Sir Herbert Read, English poet and art historian. It is an indication of a society’s cultural status and its artists’ ambitions. A club’s obsession for lush grass of the conventionalized color green should play upon the conscience of every thinking golf club board member. Read was knighted for his literary service to the arts in society. His quotation below is relevant to institutions as well as cultures, clubs and individuals and the things that people make; for instance, the institution of golf and the art of making golf courses. Courses consist of artistic and aesthetic landscape components, forms and features. Read said: “The degree of conventionality of all art forms is directly related to the degree of decadence of that culture. Whether an individual, or country, or culture, the great cultures of the western world have undergone periods of greatest artistic expression at the height of their cultural period, then the art forms pass a stage of refinement into a stage of classicism, then conventionality. Shortly thereafter the culture has passed into a period of inactivity and decay.”

There will always be some applied arts in different stages of decline or reform. Most arts in America appear to have diversity and creativity in their art forms, however, conventionalization of pure color green for golf course fairways and margins is more indicative of regressive artistic practices. This regressive trend is aided and abetted by interests and motivations of non-players associated with the game. An example of course beauty aggrandizement by non-golfers is the behavior of TV producers who have not been enamored of mixed color grass. They have been known to ask course owners to dye their grass greener for TV events. Ted Steinberg (b1961), author of American Green, wrote: “To make the scenes more beautiful to the viewing audience the media’s request was: fertilize this … paint that!” (37)

To dye and paint grass to achieve a landscape effect is just the tip of the iceberg of over-indulged pursuit of beauty through contrived landscape effect. In the Northern U.S., bluegrass provides a better playing surface and needs less maintenance than bent grass, but the course owners prefer tightly mowed bent grass because of its color contrast to bluegrass that is used for rough. Here is another case of the pandering of visual tastes that have trumped intelligent maintenance practices. This is fine for the interests of non-players but another obstacle for players.

You write, “The book’s purpose is to entertain readers with watercolor paintings of interesting golf landscapes while beginning a dialogue in the golf world that will seek to understand the underlying cause of golf’s decline. Without understanding there can be no solution to decline of the game.” Everyone acknowledges a decline in golf over the past decade and yet it is an uncomfortable subject for golf-centric media to cover – equipment manufacturers hardly want to spend advertising dollars with entities that warn of golf’s decline. Does the growth that occurred in of the 20th century and the decline in the first decades of the 21st century portend a cycle? If so, how is further decline prevented so that the game may attract more players and attain stable growth?

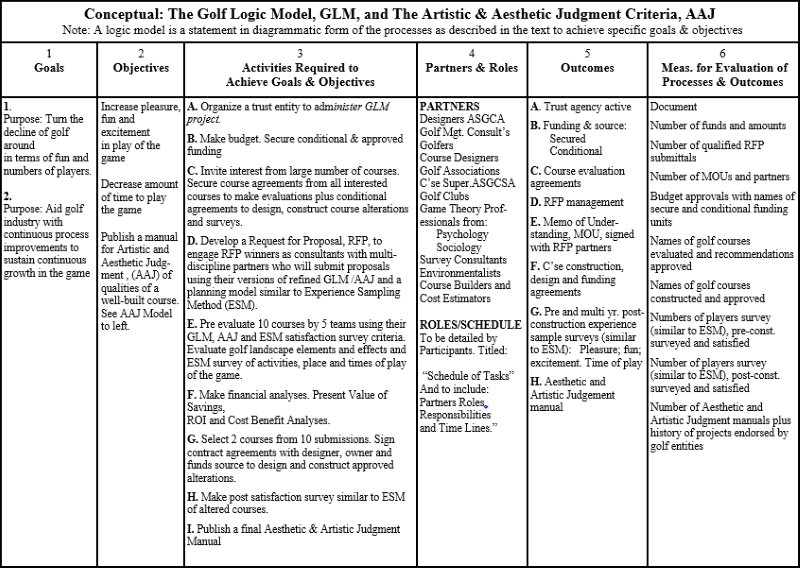

The book offers no solutions to the decline, only a process for understanding the cause, an experimental project based upon the premises of the books thesis, then options as outlined in the Golf Logic Model below for measurement and evaluation of a solution.

The authors have a story that needs to be told that provides a starting place for the process. The story needs to reach players where initiatives of a turnaround are most likely to occur, rather than non-players associated with the game. In order to reach the world’s 57 million golfers, we determined that the most effective way to interest readers is with delightful golf watercolor landscape paintings that would be an allurement to more substantive texts.

Yes, I am also concerned about the stance of the golf-centric media because of the dearth of articles with any thought provoking insights into the decline of the game. Typical of my concern is the message that I got in my follow up with the author of the magazine story: American Golf In Crisis-Where Do We Go from Here. The author told me that the magazine’s readers were not concerned and were comfortable with the present state of the game.

These are but distractions to your main question as to how might golf attain a continuous, stable growth in numbers and interests of players? The answer lies in an evidence proven process such as the proposed, Golf Logic Model, shown below.

The process begins with understanding the problem. In classic planning models such as the Logic Model, once a problem is understood, a solution becomes readily apparent.

However the solution must be tested in real time and outcomes of user satisfaction, financial cost benefit analysis and present value of savings measured. The evaluations and financials should be done on a wide basis, useful to individual courses and their decision makers. Otherwise it will not be accomplished on an individual, club to club basis because of its involved time and expense. The conceptual GLM is a planning technique that is used by many institutions and industries world-wide in attaining specific goals and objectives, evaluating processes and outcomes and overcoming obstacles to goals. This Golf Logic Model is discussed throughout the book and is proposed for the immediate purpose of assisting the golf industry in turning the decline of the game around and establishing a sound basis for sustainable growth.

Ironically, the interests and life blood of golf product manufacturers, product advertisers and the golf centric media are dependent upon the health of the game. Leadership in support of and interest in implementation of the Golf Logic Model would logically come from the golf product manufacturers and advertisers for they have the capabilities to influence participation with diverse interests from the media to planning partners in successfully pursuing goals and objectives of the Golf Logic Model.

In a lot of ways, you are a lone voice in the wilderness. A few people like golf historian Melvyn Morrow have sounded the alarm but otherwise, I see the same wastefulness from pre-2008 creeping back into the game.

One thing that appears certain is that if we want to reverse the decline and bring back more fun into the game that we take a better look at course design and maintenance, the motivations and interests that influence it and encourage cost effective reforms that will provide more fun and pleasurable excitement of the game, similar to the objectives of the above GLM.

What I believe that Morrow is talking about that is similar to my thesis is that the visual pleasures of contrived landscape effects of the course have come about at the expense of fun and pleasurable experiences of the game. Where does it end – and at what expense? If we get the message, reversing golf’s decline will come from basically two initiatives, a slow process of incremental improvements of individual courses and a process similar to implementation of the Golf Logic Model that would be more expeditious and cost effective.

The eminent historian, Thomas MacWood (1958-2012), in his GCA “In My Opinion Essay, ‘The Early Architects: Beyond Old Tom,” June 2008 adds validity to Morrow’s essay. MacWood’s interesting research supports Morrow’s point that history has ignored some of the 19th century contributions to the game. “All the commentators analyzing this period were in agreement … a good deal of mediocre architecture was produced. Had there been only one or two critical voices perhaps it would be open for debate but the commentators were unanimous in their disapproval.” (38)

There are many inland courses of that period that were exceptions, having stood the test of time. Many today, with original routing little changed, are considered more enjoyable to play, one reason being that there are few obstacles of landscape effect such as present on many modern day courses. Those early unadorned courses, absent of contrived landscape effect were given short shrift as the movement to improve scenery of inland courses moved inexorably onward in pursuit of good taste. To quote MacWood: “This period can claim its share of historic designs, courses like Prestwick, Hoylake, Machrihanish, Sandwich, Portmarnock, Dornoch, Cruden Bay, Lahinch, Rye, Ganton, Myopia Hunt, New Zealand and Worlington, and for that reason cannot be considered a Dark Age.”

The avowed objective of course design from a century ago remains unchanged; which is: “To design courses which shall give the greatest possible pleasure to the greatest possible number.” Invariably, every designer’s statement of course design embodies this idea. However, with respect to the idea of courses giving pleasure, there has been a great deal of variation in the application of this objective. The difference lies in understanding and accommodation of pleasurable and beautiful experiences for all skill levels. Scientific research of the phenomena of pleasure and the qualities that make games fun in our culture today are discussed in detail in the book. Pleasure is a sense of beauty that is derived from sensations by all of the senses, influencing emotion and intellect. Aestheticians and philosophers since the age of enlightenment have successfully advanced the idea that sensations and/or objects that provide pleasure are beautiful.

A great deal of variation in the phrase ‘greatest possible pleasure’ is evidenced in the following quotations from notable golf writers and designers over the last century. At the time courses were beginning to be designed and built by men rather than predominately by nature, Bernard Darwin and C. B. Macdonald related experiences of beautiful emotional and intellectual sensations on the golf course, none of which were of a visual character. Now, one hundred years later, contemporary designers Tom Fazio (1945) and Tom Doak (1961) talk about beauty more in terms of viewing a fine golf landscape and making beautiful golf holes.

Quotations of prominent golf writers and designers from Darwin to Doak, 1909 to 2010, reveal a trend of emphasis and attitude that shifts from beauties and attractions of the game to visual beauty of the course.

Bernard Darwin, famous English golf writer, expressed beauty in terms of his pleasurable thoughts and feelings with play at St. Andrews: “…beauty in contemplations of playing the banks and braes that guard the holes without need for bunkers.” This was characteristic of what was considered as beautiful about golf in 1909

C.B. Macdonald, most famous of early American designer, elaborated upon pleasurable excitement in terms of emotional and intellectual experiences as: “Beauty in contemplation of wind and hanging lies.”

Walter Travis (1862-1927), commented upon soulful delight, an intellectual and emotional sense of beauty of experiences playing his greens as: “The putting greens are real beauties and will delight the soul.” And of the simulation of being in a “state of flow” in striking a series of uninterrupted good shots, exclaiming; “I was in that golfer’s seventh heaven.”

Dr. Alister MacKenzie stated that: “The beauty of golf courses in the past has suffered from the creations of ugly and unimaginative design.” MacKenzie sought beautiful surroundings, as he wrote: “The chief objective of every golf architect or green keeper worth his salt is to imitate the beauties of nature so closely as to make his work indistinguishable from nature.”

Harry Colt wrote: “The landscape might have been made more pleasing to the eye… by planting judiciously… pleasure …would be gained… from playing the game amidst pleasing surroundings.”

George Thomas, Jr.(1873-1932), whose 30 years of rose hybridizing ingrained in him an appreciation of the sensitive relation of function and aesthetics, consistently incorporated: “Functionality and beauty” in his work.

A.W. Tillinghast stated that his objective was: “… to make the hole a challenging test and as beautiful as possible.”

Dr. Michael Hurdzan (1943), wrote: “The wow factor for beauty that had ranked 10 is now 2 in importance of design.”

Thomas Fazio’s idea of enjoyment on a golf course included experience of beauty; he stated that: “Blending art with science to produce beautiful places people can enjoy…” and “…that experience of beauty is in viewing a fine landscape; are part of the enjoyment of golf.”

Tom Doak, quoting from Dream Golf 2010, that in order for a course to take its place at the top of the World’s 100 best course lists, it would require that the designer: “Make… holes as beautiful and as interesting as possible.”

Thank you for sharing your very interesting perspective over these past several months.

The pleasure was all mine. Landscape effect is a very important subject and I hope we have given people plenty to ponder. As we reflect upon this great game, let us ponder about that which has been good for the game and that which has not been in the best interests of the players of the game.

THE END

Footnotes:

20. Brolin, Brent C., Flight of Fancy The Banishment and Return of Ornament, St. Martin’s Press, NY, NY,

1985. The source of much of the material in this and the next paragraph is from Chapters 4 through 6.

21. Calusa Pines, FL, GolfClubAtlas.com, January Feature Interview, 2009.

22. Gerard, Alexander, Esssay on Taste, ibid 20, pg.73

23. MacWood, Thomas. GolfClubAtlas, Arts and Crafts Golf, Part III

24. Wethered, H. N. & Simpson, T., The Architectural Side of Golf, Longmans, Green, Ltd. 1929, reprint Ailsa, Inc.,

2001, page v. Author’s Preface

25. Macdonald, Charles Blair. Scotland’s Gift – Golf, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1928, reprint Ailsa Inc.,

1985, page. 29.

26. Ibid 20, page. 93

27. Ibid 20, page 107

28. Hutchinson, Horace G., Golf: The Badminton Library, Longmans, Green, Ltd., London, England, 1890, page. 321

29. Ibid 23, Part III

30. Hawtree, Fred. W., The Golf Course: Planning, Design, Construction and Maintenance, E. & F. N. Spon, London,

England, 1983, page. 23

31. Wethered, H. N. & Simpson, T. The Architectural Side of Golf, Longmans, Green, Ltd.

1929, reprint Ailsa, Inc., 2001, page. 9

32. Ibid 20, page 1 Foreword

33. Ibid 30, Preface page 12.

34. Fazio, Thomas. Golf Course Design, Harry N. Abrams, New York, London, 2000, pg. 53

35. Cornish, Geoffrey and Whitten, Ronald. The Architects of Golf, Harper Collins, NY, NY,

1993, page. 177

36. MacKenzie, Alister. The Spirit of St. Andrews (Manuscript originally written in 1934),

Broadway Books, NY, Sleeping Bear Press, 1995, page.50.

37. Steinberg, Ted. American Green, WW Norton Co, 2006, page 94

38. MacWood, Thomas, GolfClubAtlas essay; In My Opinion The Early Architects: Beyond Old Tom,

June 2008, The closing 6 paragraphs of his essay relate to the material quoted here.