Feature Interview with Dave Axland

January, 2003

A Kansas native, Dave Axland is a graduate of Kansas State Universitys turf grass management program. He began his career in golf course design and construction working under Bill Coore at Kings Crossing in Corpus Christi, TX during the mid 1980s. Since then, Axland has continued to work with Coore and his design partner, Ben Crenshaw, on a number of projects, including Kapaluas Plantation course in Hawaii, Chechessee Creek Club in South Carolina, Friars Head on Long Island, New York, and Old Sandwich, presently under construction near Plymouth, Mass. Axland and his design partner, Dan Proctor, have designed and constructed three golf courses of their own at Delaware Springs in Burnet, Texas, Wild Horse in Gothenburg, Nebraska, and Bayside in Ogalalla, Nebraska.

1. How did Dan Proctor and you unite to form Bunker Hill? What were your goals in the beginning and what are your current prospects?

I met Dan in 1986 while working at King’s Crossing Country Club in Corpus Christi, TX. Dan was working in golf operations and I was the assistant golf course superintendent.

We were both pretty active golfers at that time and enjoyed traveling the state to study golf courses and play the game. The idea to try to get involved in the design and construction of golf courses occurred sometime during those travels. We thought that there might be an opportunity for someone to work with people in smaller communities and with limited budgets, to help those communities get the most out of their properties and resources.

We had probably seen just one too many costly earth moving assaults of a nice piece of ground when we decided to form our partnership. Dan and I were probably not too dissimilar to some of your readers avid golfers looking for an opportunity to design and build a golf course. For whatever reason, whether it was luck, fate, or having a friend like Larry McNeely, who recommended us, we were given our first opportunity to go to work at Delaware Springs, in Burnet, Texas.

Our goal remains the same today as it was then to build affordable, quality golf courses. Were looking forward to doing more work. In particular, a potential new course project on the Hermsmeyer Ranch in Ainsworth, NE, which shows great promise.

2. Both Dan and you have worked on a number of projects with Bill Coore over the years. What influence has Coore had on Bunker Hill?

Dan and I have worked with Bill, off and on, for close to 20 years now. [128]Bill Coores the person most responsible for our interest in golf course architecture.

Most members of the Coore and Crenshaw team didnt start out with a goal to become golf course builders or designers. Most of us were simply on a crew that was doing the construction work on a Bill Coore, or a Coore and Crenshaw project. But those of us who found interest in questions like, Why is that bunker placed there? Or, Why do you think this is the way it is? have stuck around.

Bills a teacher. He gets the most out of his men and their individual talents by allowing them to work freely within the Coore and Crenshaw framework. Because Bill and Ben spend so much time on-site throughout the development of their courses, there is no great time pressure to make instant decisions. They allow completed work that might be different from a preconceived notion to sit for a while before refinement or abandonment.

Bills methodology is a lesson in managing and developing a team concept. Hes been a great influence in that regard. Yet within that concept he encourages each of us to refine our talents and is supportive of those of us pursuing independent design careers. Rod Whitman is another member of the Coore and Crenshaw team who continues to try to develop a business and reputation of his own.

The Coore and Crenshaw team is quite a collection of individuals a group of men from very diverse backgrounds and experiences working together. Within that team, the parts are interchangeable. A guy who just designed a golf course, like [129]Rod Whitman or Dan for example, might be running a tractor, an old job boss may be roughing in a green or digging a bunker, while an equipment operator might be running the job in question!

This summer Dan and I went up to Canada to help Rod with a new 18-hole project in Edmonton, Alberta (Blackhawk GC). Now, with that course complete (scheduled to open in July 2003) Whits helping Bill and Ben with a new project in Plymouth, MA. Its a great benefit to study how people from similar design backgrounds apply the same, time proven, basic concepts to different situations. It gives you a fresh perspective on certain things and helps keep the work from getting stale or repetitive.

What Bill and Ben work so hard at is finding ways to develop golf courses that not only look different from previous work, but also courses that play differently.

3. You were involved in the construction of the Plantation course at Kapalua, Hawaii. What were some of the major factors dealt with during construction?

As I recall the major factors at the Plantation course were the large scale of things the Pacific Ocean backdrop, strong wind potential, and the severe, sloping ground.

During construction, when a green was roughed in that looked nice, the slopes were nearly always still very severe because of the native slope of the property. Conversely, when something was leveled up it had a benched in, artificial look. It was difficult to achieve something in between.

One of the most interesting stories is about building the first green at Kapalua. Jerry Clark, (better known as Scrooge) a long time Coore and Crenshaw builder and shaper, had that green roughed in and it looked like a backstop, sloping back to front. Scrooge got off his bulldozer, with parking brake off and the blade off the ground, to visit with Bill and Ben and, as they spoke, they noticed the tractor moving, on its own, towards the back of the green! Even though that green looked like it was sloping back to front, the opposite was true. The inherent slopes there, at Kapalua, were that severe.

All things considered slope, wind, and scale the general thought for most of the holes at Kapalua was to give golfers plenty of room to play the game and to develop situations where they could make shots using slopes to their benefit.

When the land worked hard away from the golfer on a hole like seven for example, the green ended up to have that same feel. Number eighteen green is another good example. That green features interesting ‘feeding slopes’ and a couple ‘gathering pin positions’ that account for the natural severity of the ground. Using slopes and having to account for them is a big part of the game on that site.

But then, further inland, the ground presented an opportunity to do something different, as was the case with a smaller perched up green at fourteen, for example. I think the end result is a well balanced course.

Kapaluas a golf course that most people have a great deal of fun playing, while others probably just wish their ball would just sit tight when it lands.

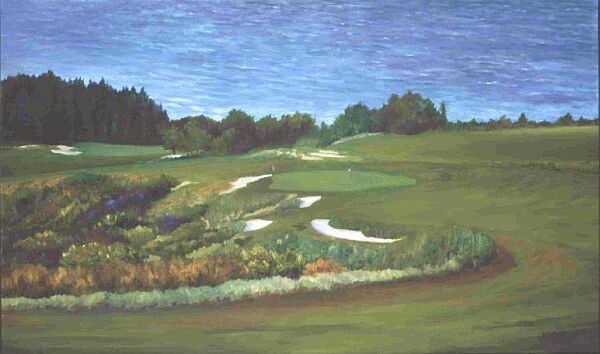

One of the game's most distinctive Home holes - the 18th at the Plantation Course at Kapalua, as captured by artist Mike Miller.

4. With Delaware Springs, Wild Horse and Bayside, Bunker Hill has a track record for building quality golf courses that are inexpensive to play. What’s your secret?!

We have been fortunate. The properties and people we have had the chance to work with have been very good.

Again, our goal is to help make land playable for golf without our work ‘overpowering’ the site. When were given a nice piece of property and we keep things simple, the result should be a cost effective, quality product.

Most of our work has been on behalf of a community trying to develop a golf course that will be an asset to its citizens. With that sense of community, local people have exhibited a willingness to donate time, materials, and equipment in order to keep the cost of course construction down. This attitude helped us greatly at Burnett, and in Gothenburg and Ogallala, NE.

Moreover, having talented associates like Mike ONeil and Jack Dredla, who started working with us in 1999 at Bayside, is a big help too.

5. What was the decision process in leaving some trees in play at Delaware Springs?

The trees we left in play at [130]Delaware Springs fall into the survivor tree category. In other words, when a tree has enough character to make it through the first clearing pass you begin to work around it and visualize the hole with and without it. As a golf architect, you have to ask yourself if a golf hole would be substantially improved if a speciman tree were removed and replaced with a contour, or bunker?

Many of the trees on the Delaware Springs site are Live Oaks. Theyre pretty good golf course trees given their natural growing habit. Live Oaks are both impressive in appearance, and they feature a high canopy that enables golfers to play recovery shots from around and beneath them.

The golfer can play under, over, or around the Live Oak in the middle of the 6th fairway at Delaware Springs.

6. How do you as an architect encourage play along the ground? Please site a specific example.

One way is to provide contour/slopes strong enough to make using them a better option for certain pins than a carry shot. This can be achieved with ‘quiet’ ground also – grades that simply work away from or at an angle to the fairway. Also, managing the soils in these areas to make firm, fast turf conditions less difficult to maintain is a big help. Equally important to the design concept is having a turfgrass manager who believes in this golfing option.

The 13th hole at Delaware Springs comes to mind as an example. It is a short downhill par 3. The right half of the green is designed for a carry shot in that a bunker guards this part of the green. The right part is elevated enough so that the transition to the left half of the green allows for a feeding slope to get to some left pins. The left part of the green and its approach ground slope away from the tee. The hole plays best from a shorter distance in that the forced carry shots to the right pins require loft.

7. Tell us about Wild Horse in Gothenburg, Nebraska, which ranked #18 in Golf Week’s Modern 2003 ranking.

Wild Horse Golf Club was the result of a group of Gothenburg residents wanting to improve the towns golf facility. Money for the project was raised by selling 1,000 shares of stock at $500 each, along with the sale of 50 residential lots adjacent to the course.

The community was very supportive of the project. Local ranch and farm owners would come by at the end of their long days with a tractor to help prepare ground for seeding. People donated their time in many ways.

Gothenburg won the Nebraska state community improvement award in 2000 for their efforts on behalf of the project. That speaks volumes.

The Wild Horse property is located on the southern edge of the Sand Hills region of Nebraska. The wind blown sand deposits have resulted in wonderful natural dunes and contours well suited for golf.

As with any good site, we started by looking for the best natural golf holes or at least the best ground on which to build quality holes. The ground on which the eighteenth hole sits today featured the only two natural blow outs on the site. That golf hole couldnt be ignored.

After roaming around for a few days, it seemed the best way to get the most out of the ground was to have the gathering point at the large hill on which the clubhouse sits. Dan most often takes the lead when it comes to our routing work, and things just seemed to fall into place when he decided on that starting point. That area around the clubhouse was big enough for a practice area as well. The holes just seemed to fit well on the ground from there, with plenty of variety in contour and wind angles.

It was also important to us to get each nine to touch on both the more severe dunes and the quieter ground as well.

Given the ever present wind, natural contours, and the opportunity for firm playing conditions, it made sense to expose as much of that ground as possible to bring that variety of natural contour into play. Having plenty of width also allowed us to present optional routes of play on most holes. We didnt want to dictate one way to play the holes, nor did we want golfers to feel like they had to get the ball way up into the wind in order to play a shot.

People who like to get the ball on the ground and be creative shot-makers, and golfers who dont like to feel they have to fly the ball all the way to the hole on every hole should enjoy themselves at Wild Horse.

Josh Mahar, the golf course superintendent, does a great job managing the playability of the ground game.

Plus, the course is affordable. An annual family membership is $400. Individual green fees are $30.

The golfer delights in the pure golf landscape found at Wild Horse.

8. Talk about the relationship between the initial development costs and the future green fees. What are the keys to keeping construction costs down?

At Wild Horse, for example, we knew that if we could work with a reasonable budget number, then the annual membership fee for families and individual green fees would be affordable. That was very important. We knew that the total debt would determine the number of outside rounds the course would need to break even in a reasonable amount of time as well, also realizing that Gothenburg, NE wasnt going to support a high green fee.

Josh (Mahar) had a good line about keeping construction costs down. He said, Get a good site and work cheap. The site does have a lot to do with the final cost of course construction, yet there are ways to economize on most projects if allowed.

The key is to stay open minded regarding agronomics, construction methods and design concepts. Adjusting the style of design to suit the strengths of a site is something that helps keep the scope of work down. This approach should result in lower construction costs, and ultimately a golf course that is more of a compliment to the ground on which it sits and the surrounding landscape as well.

We have leaned on a couple of independent agronomists over the years. Guys like David Gregg and Dick Psolla, who have been very helpful. Our conversations with them usually start out with a simple question like, Heres what we have to work with, and heres what we would like to achieve. How can we make it work?

For example, the site conditions at Delaware Springs were rocky. We would have had a hard time affording greens with extensive internal drainage. So David (Gregg) came up with a material that allowed us to cap both the ‘push up’ greens and the low rocky green sites.

At that time, Dan and I had seen enough of the elevated, big fill-type greens, so we wanted to build something a bit more low profile.

Good surface drainage and the desire to keep back line heights in check was a goal. Furthermore, we wanted to provide a ground game option. The resulting slopes in and around the greens work with natural grades or across them, but seldom against them.

In some cases the natural grade of the ground determined the final grade of the green, and also the preferred line of play. On more than a few holes, we worked backwards from those spots in the greens to the landing area, and then back to the tee in an effort to challenge specific lines of play.

One advantage to the type of greens construction method we employed at Delaware Springs is, there are bound to be at least a couple greens that are a little different from the rest. Whether a bit more firm or faster growing, this occasional lack of consistency, or predictability in playing conditions and slope encourages study and shot making choices beyond aerial attack. There is some advantage to local knowledge at Delaware Springs over the first time player with his laser-distance finder.

Contour is a good way to balance the opportunities for power and finesse play. Options seem to confuse the high-tech power player. There is some adventure in aiming away from the hole and watching your ball react to the ground.

One of Coores favorite stories has to do with the greens at Delaware Springs. A man who had just played there asked Bill, Do you think those guys got the plans backwards?

9. With its gently rolling terrain and sandy soil, the Wild Horse property was ideal for golf. Soil conditions aside, how important is interesting topography to high-quality golf? In other words, when working with a relatively flat site, is it necessary to move tons of earth to create interesting golf?

The game can be enjoyed on many different types of ground. Thats not new information.

We like to say that a good site, or one that we would enjoy working with would be relatively flat, preferably with sandy soil. It would be fun to see what could happen by simply digging bunkers and making ‘piles’ with the excavated earth on flat ground similar to the work done in the early 1900s at Garden City Golf Club, and some other courses built around the same time instead of carving up or re-contouring an entire site.

Simply dumping piles of dirt, then hand raking or harrow dragging them tends to create movements that have a ‘pre dozer era’ type look.

10. Please describe the opportunity/challenge of Chechessee Creek Club.

The goal at [131]Chechessee Creek was to build a new golf course that had an old course feel. We wanted the architecture to be quiet enough to resemble golf course work of a past era, when it was not desirable or even possible to re contour an entire site.

The principle challenge at Chechessee, besides getting that flat site to drain without moving much dirt, was to develop bold golfing features and yet not overwork the site to the point that you wouldnt appreciate the specimen trees or inherent Low Country nature of the property. Seth Raynors work at nearby [132]Yeamans Hall and the Country Club of Charleston served as somewhat of an inspiration or model. We aimed to create strong green and bunker features at Chechessee in the image of Raynors basic style.

A friend once asked me to pick the course I would most enjoy playing long term or the one I would want to call my home course. I thought of Chechessee. Its a golf course that you would enjoy every bit as much in 20 years, as a golfer whose power game has perhaps faded but can still rely on decision making and finesse for success.

11. Please detail a hole at Chechessee Creek Club and why you enjoy playing it so much.

The 400 yard fourth hole is a fun one.

There, your tee ball should favor the left side of the fairway. The angle of the cross bunker sets that up in that the further carries move you left. Bill and Ben scattered bunkers down the right side of the hole. They create some indecision from the tee, unless you have played there before.

Advantage was given to the left landing area by elevating this area, pointing the narrow green in that direction, and bunkering the green on the right side. How you play your second depends on position and how good you feel about your iron game that day. Generally, I will bale short or left of the green and hope to get up and down for par.

The 4th at Chechessee Creek as seen from the tee.

12. Do you have a favorite concept for an ideal hole?

A favorite type of hole is a par 4 with at least two obvious optional lines of play. One line requires a carry over something that, if successful, results in an approach to the green from the best angle. That preferred angle should be determined by the tilt of the green surface, or a single greenside bunker. The other option of play is to avoid the carry from the tee, but then face laying up to an advantageous spot short of the green with the second, and playing an approach putt or chip into slope.

This type of hole works best if all golfers play from the same tee. There are many examples and variations of this basic, time proven concept. One of the better ones is the 10th hole at [133]Riviera. Its one thing to design a golf course in concept, on paper, in two dimensions.

13. How does Bunker Hill ensure concepts are properly implemented, in three-dimensions on the ground?

Between Dan and I, one or both of us is on-site everyday throughout the development of our courses. We also carry out much of the construction work, from preliminary shaping to the hand-crafting of a putting green personally.

14. Which golf course with which readers may not be familiar is a personal favorite of yours, and why?

One of my favorite places to play while working in Burnet was the municipal golf course in San Saba, TX. It was designed by Sorel Smith, who worked with golf architect Ralph Plummer. Construction costs for both nines at San Saba totaled about $200,000. The course has plenty of strategy and is great fun to play. What else do you need!

15. Please comment on the evolutionary process that you witnessed at Friar’s Head.

The land at [134]Friar’s Head has more variety than any we have had the opportunity to work with. As such, our challenge was how to best meld the very different portions of the property together.

About half the golf course is located in heavily wooded, severely contoured sand dunes where elevation changes of up to 80 feet are found. Parts of it overlook Long Island Sound. The ground and views are both dramatic and impressive. The other half of the golf course is situated in a farm field where you have everything from flattish ground to a 4-acre sink hole, 30 feet deep. Potatoes and sod were grown in the field, so its soils were obviously much heavier than in the dunes.

Friar’s Head was the most complex site we have ever worked with. It is not the type of property that makes you feel like you know what is best for it at all times not if at the end of the job you evaluate your efforts by asking the question, ‘did we get the most out of this piece of ground?’ From that standpoint it was the most challenging site to work with since the Sand Hills.

Design input at Friar’s Head was similar to most projects specific in most instances and general in others. We just had to be very patient and allow the ongoing work to influence/dictate future moves. Although that process was no different than on other C&C projects, it just seemed like at Friar’s Head we needed to be more prepared for the unexpected. To try and force things to happen would have been a mistake. The designers didnt judge work quickly with the owner allowing them the time for such study.

The process of building Friar’s Head was great fun, especially if you believe that one of the worst things that can happen to you as a designer is to get exactly what you expect.

Axland ran the Friar's Head project on Long Island for Coore & Crenshaw. Pictured above is the 9th green complex.

16. In general, how would you characterize the strengths/weaknesses of courses built in the United States in the 1980s?

To be honest, I haven’t looked at many courses built during the 1980s. In my travels, I usually try to find an old course like a Ross or Maxwell-designed muni, with a single row, quick coupler irrigation system. That’s where I tend to find the most interesting and fun golfing experience to be, places like that. Fortunately, most of those types of places lacked the money to modernize over the years.

I have looked at a few of those 1980s and ’90s era courses though, and was always hoping to see something different. But, with few exceptions, I felt like, if I’d seen one I’d seen them all. It is difficult for me to appreciate a golf course or its architecture when too much is happening all around you. Two or three things to think about per hole is about all my brain can handle before visual overload usually around the 13^th or 14^th hole.

Maybe the best thing about some of that work done in the 80s that involved massive earth works is that it lead to an appreciation of a more frugal style of design work that you can look at and say, I know why they spent the time and resources to do that. But, I’m sure in a few years people will tire of some the more restrained work that’s being done these days and move on to something else again. Art does seem to travel in circles.

Hopefully though, we’ve evolved to a point where building hills that parallel both sides of every fairway to isolate golfers from the rest of the course and other players has proven pointless.

17. Prairie Dunes occupies an unusually fine stretch of rolling dunes with sandy soil. As a native Kansan, are you aware of any other such areas within the state with the potential to yield a course of such outstanding quality?

Sure, there are other areas in the state with wind-blown sandy soil deposits and rolling terrain. One area that immediately comes to mind is south of Garden City. For years, Ive heard people say that they are going to build something similar to Prairie Dunes or at least a few greens comparable to those great greens at Prairie Dunes, (I am one of those people). But, I havent seen a new course yet that compares; not even a single green that ranks with Maxwells best at Prairie Dunes.

18. Are greens as small and contoured as Prairie Dunes (4,300 sq. ft. on average) a design option of the past?

I dont think so. They should be a design option of the future given the equipment we are allowed to use today. Small, boldly contoured greens might be the best prescription for the ever-increasing distances we are seeing out of the modern golf ball.

The End