Feature Interview with Bob Labbance and Kevin Mendik

April, 2008

For more information on Bob Labbance, please read his Feature Interview from November, 2000 on this site.

For more information on Kevin Mendik, please read his In My Opinion piece entitled The Challenges of Restoring a Classic American Golf Course on this site.

Wayne Stiles is top row second from the left in this photograph of the MGA Team Champions from 1911.

How did you go about your research for The Life and Work of Wayne Stiles? After all, as you state in the Introduction, “Stiles was not a prolific writer like Walter Travis, nor did he appear to strive to get himself noticed as did AW Tillinghast.”

BL: The genesis of this book really begins in the 1980s when I met Geoffrey Cornish. After raving about the Rutland Country Club and the Country Club of Barre, Geoff told me that he felt Wayne Stiles was the most underrated golf course architect in the Northeast if not in the entire country. Often confused with Donald Ross â€who Geoff insisted would never want credit for work he did not do, nor would he ever want to overshadow a contemporary â€Stiles nevertheless worked in his shadow. It took some time, money, patience and resources but I feel we have finally righted that wrong.

KM: The idea for Bob and I to do a book on Stiles grew out of a few earlier projects I worked on at my day job. I found out about the Fiske Warren plan several years ago while working on a Stiles article for The New England Journal of Golf in 2004. I mentioned to a few of landscape architects who I work with at the National Park Service that I was researching Wayne Stiles and one of them made an erroneous but understandable association with Ezra Stiles and suggested I visit the Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation which has over 1 million documents from Frederick Law Olmsted and his sons. Ezra turned out to be unrelated, but as an NPS employee, I was able to go directly to the Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site in Brookline and was literally led to the Fiske Warren plans. That in turn led to me being asked to do a profile of Stiles for an upcoming government publication entitled The Pioneers of American Landscape Design Volume II. Government publications can take quite some time, but for more information about that book, which will include profiles of Stiles, Tillinghast, Macdonald and Bendelow, go to www.tclf.org and query Pioneers. I started poking around on google and found the Mt. Hope Farm plan which I certainly wouldn’t have found if Williams College had not digitized that portion of their archives. Bob, being the prolific gatherer of golf related information that he is, gave me some early research done by Gary Sherman of Haverhill, NH which related to Stiles’ personal life, such as his family and several places where he lived.

Bob and I had been talking about doing a joint golf book and the idea to do a full blown biography of Stiles just sort of occurred to both of us at the same time. By then, I had been yammering on for a year or two about all the interesting Stiles stuff that was out there. We had two or three key pieces of information that we used as our initial roadmap. I was able to expand on Gary’s research and nail down a few more key pieces through the online US Census information. Then Bob found the 1924 Fraser’s list which greatly expanded on the list from The Architects of Golf.

As for the nuts and bolts research, we used every tool we had available, from the extensive capabilities of Google and modern sources such as Proquest and the U.S.G.A.’s S.E.G.L. database to old fashioned perusing of used bookstores. I was in an old bookstore in Maine, came across Kennebunk In the Nineties and was actually flipping pages when I spotted a paragraph about a Stiles from Needham who had bought a cottage on Lord’s Point. We visited libraries and historical societies in the various towns where their courses were located. Living in Newton made certain elements relatively easy for me when researching Stile’s life history, as I was able to visit all the towns where he lived and go through their records in person. Of course, we had to visit any and all courses on the lists, and that process turned up the expected troves of information at some courses (East Mountain) and literally nothing at others. Some people found us through the web, like Jean Pettigrew, John van Kleek’s daughter and Duane Dietz, who was researching Butler Sturtevant. Duane had later firm course lists which literally doubled the master course list. Even well into last fall we were still coming up with new courses, several of which post dated even the latest firm course lists, such as Olde Salem Greens and East Mountain.

The competition history grew out of my first visit to Brae Burn. I was doing my usual wandering of the clubhouse and came across several boards with W.E. Stiles on them. A few more visits later and the folks there were good enough to open up their archives, which turned up literally dozens of references to not only Wayne’s, but his brother Harry’s competition references. The first thing I saw when I walked in the door to that lovely room was the photo of the 1911 MGA Team taken just by the first tee, literally just outside the window and three floors down.

We could have kept on researching forever, but Bob wisely pointed out that a 600 page book would simply be too heavy and no one would read it.

What in Wayne Stiles’ background led him to design golf courses?

KM: We don’t really know which came first, his attraction to the game or his attraction to landscape architecture. We do know that by 1901 he and Harry were being mentioned regularly in the top amateur competitions of the day. Playing in the top amateur circuit, he was certainly connected with folks at the top tier clubs, and perhaps through those associations, he was led to the job at Brett and Hall. While there, he interacted with several rather well heeled clients, many of whom had strong interests in golf, such as Edward Harkness. As a top young amateur working as an associate in Brett and Hall, he may have been in demand as a partner in various club events, just as we all like to bring a ringer to our member guest tournaments today. We simply don’t know why his competitive career seemingly ended by 1915, nor do we know how his natural evolution from landscape architecture to golf architecture came about. We do know that his LA background gave him a critical understanding of how landscape plantings and especially trees would impact strategies of play on various golf holes, and especially how trees would grow over the decades, and continue to change the way a hole might play.

When and where did Stiles build his first great course?

KM: For me, the answer is simply a subjective call. From a purely historical perspective and given that it was the only Stiles course where a major was contested, Norwood Hills stands out.

BL: Wayne Stiles’ first great course has to be Norwood Hills Country Club in St. Louis. How Stiles became associated with an organization in the Midwest remains a mystery. All of his work until that time had been done in the Northeast, whether it was landscape architecture or golf course design. His 18-hole course at Nashua Country Club was surely better than most layouts from 1916 and perhaps that is what led to the work in St. Louis.

From the 1890s on wealthy business owners from the industrial Midwest escaped to the relatively clean environments of New England for part of each summer. One such example is the Abenaqui Country Club in Rye, New Hampshire â€founded by St. Louis transplants. It is not inconceivable that someone from that club saw his work at Nashua and recommended him for the job in St. Louis. In any event, Stiles, before his association with John Van Kleek, landed the contract to install 45 holes of golf on a rolling verdant expanse of land perfect for golf. The architect designed a championship course, a playing course and a nine hole learning facility. Using his training in landscape architecture he identified which trees to cultivate, which trees to eliminate, and where to plant others that, over time, would not restrict the options available to the player but rather enhance the strategic possibilities.

It is a testament to his skill that magnificent specimen trees remain today; the golf courses have needed little modernization; and the club has flourished â€maintaining one of the largest memberships in the region. Praise for the course at the 1948 PGA championship was universal. Although the nine hole course is gone the two remaining 18-hole layouts are beautiful and an absolute pleasure to play.

How many courses did he design solo before partnering with Van Kleek?

BL: Stiles designed approximately 15 courses before his association with John Van Kleek. He probably had another half dozen or more on the books in one form or another as he added a partner. Geoffrey Cornish postulates that although the men worked separately they would confer, consult and discuss their separate plans. Ample evidence suggests that Stiles made frequent winter visits to Florida where Van Kleek ran the southern business. What correspondence still exists reiterates that the two kept each other informed of all projects and valued the other’s input. Architectural partnerships are often on paper only and although the evidence of Stiles’ style prior to the partnership can be demonstrated it seems that maturation and advancement characterizes the work from 1924 to 1931 when the partnership dissolved.

What strengths did Van Kleek bring to the partnership?

BL: Stiles knowledge was largely the result of practical experience and mentoring from two widely respected landscape architects. He never attended college and whatever scientific basis he utilized in his practice was the result of seeing technical drawings and engineering plans at the office in Boston. Long before Robert Trent Jones claimed to be the first golf course architect to graduate from Cornell University, John Van Kleek actually was, completing his program of study in 1913. As a result he brought technical expertise, text book learning and scholarly achievement to the partnership. He also brought contacts throughout the academic community and through an established practice in Florida a reputation in an area of the country that Stiles had yet to visit. Where his flair for golf course features may not have been as developed as Stiles, his understanding of the technical aspects of design and of managing a large firm complemented his partner’s abilities.

In general, what are the defining characteristics of a Stiles & Van Kleek course?

KM: If I had to list one, it would be the use of high ground for greens and tees. This may sound simplistic, but for those of us fortunate to have visited as many Stiles courses as we have, its hard not to notice how often one hits an uphill approach shot or tees from an elevated spot. Approach bunkers are another common feature, and looking at the old photos shows us how many more are buried. His use of greenside mounds which carried onto the putting surface is certainly a dominant feature, especially at courses which are on relatively flat terrain. East Mountain, with 17 original greens, is a great example of this.

BL: I would add that Stiles seemed to accommodate the skill level from a wide range of players off the tee. Drive zones were ample but the correct approach was often subtly realized. Being on the wrong side on a generous fairway did not prevent the player from achieving the putting surface and depending on pin placement it may have resulted in just as makeable a putt. But the skilled player who worked backward from the ideal position on the green often found that the correct side of the fairway yielded a clear path to birdie.

Especially in the northeast, courses that were designed by Stiles & Van Kleek are sometimes erroneously credited to Donald Ross. Would you agree that their design styles had similarities?

KM: Most of the architects working during the first two or three decades of the 20th century utilized each other’s design elements, expanded on them and developed their own types of holes. Macdonald may be rightly credited with bringing certain types of golf holes to America, but I think all the Golden Age designers brought new concepts to the game, borrowed from what nature laid down and looked to each others work for inspiration. I don’ t really think a design element such as the false front is rightly credited to any particular architect; nature makes slopes and golf architects find them quite suitable for challenging green locations. Nor is the use of greenside mounds feeding into a putting surface a uniquely Stiles design element. It is simply that Stiles utilized that element often just as Ross utilized the crowned green. What went on in the 1910’s and 1920’s is not really different from what today’s architects employ when bringing similar elements to their designs. Gil Hanse, Tom Doak and the team of Coore and Crenshaw have all played a big role in the resurgence of the classic or minimalist design style we enjoy on today’s new courses, and there are certainly common elements to wonderful places like Pacific Dunes, Friar’s Head and the Boston Golf Club. But again, I don’t think any of them believe they created certain types of features. Having rough and natural bunker edges is a design element that nature employs when she makes golf terrain; utilizing that element on a particular hole or throughout a course doesn’t rise to the level of having the right to patent any particular feature. Good thing patenting golf holes didn’t occur to CBM.

On many occasions, we’d contact a course and the first response would be Stiles who, we’re a Donald Ross course. Given the cachet that Ross has for many golfers and golf historians alike, many clubs simply want to believe that they were designed by Ross, when there may have been many golf architects involved over the decades. In many cases, both Ross and Stiles worked on the same course, in some cases like Augusta in Maine, they each worked on separate and distinct nines. In other places, they altered each others work. Although quite prolific, it is no secret that Ross never visited many of the courses he is credited with designing. Simply having his name on a design lent value to the course.

BL: It is very easy to claim Ross and Stiles had similar design styles. However at least two people who worked at the same time they did and knew what their courses looked like when they were installed â€and not what they have become today â€feel that Stiles’ work had more in common with designs produced by A.W. Tillinghast than Ross.

Are there design differences between Stiles & Van Kleek and Ross that standout?

KM: As for distinctions, the one that pops out for me is Ross’ use of the putting surface as the zenith of a green complex, whereas Stiles often employed the use of greenside mounds, hillside green locations and bunkers above the greens to offer the golfer who missed the approach shot a downhill chip to the green. One aspect of their respective work that is quite different is that unlike Ross, who may not have visited perhaps half the courses he is credited with designing, Stiles is believed to have actually been to each property he is credited with, likely exceptions being the several dozen Florida designs he and Van Kleek churned out in around 1930 which never got built. Personally I simply can’t imagine how a golf architect could design a golf course from just a set of topo maps without having visited the property to get a sense of how the land moves, how the wind blows and the interaction of the various watercourses. As Geoff Cornish pointed out, Wayne would walk the land and design the course with his eyes.

BL: It is my guess, given the mundane nature of some Ross sites that Donald was much more likely to accept a given piece of land secured by the club in advance of his initial visit. Correspondence notes in several instances, and I would extrapolate from these, that Stiles was more selective in choosing sites, always preferring land with substantial movement as his canvas.

KM: In some cases, notably on his collaboration with the Olmsted Brothers on the Trapelo GC project for Fiske Warren, he outlined routing problems with the site for an 18 hole course as opposed to the nine he had designed.

For those interested in gaining a better appreciation of their work, what three courses would you most recommend for study?

KM: First off, I find it hard to pick just three, so I’ll pick six public courses to start.

For those planning a Stiles vacation tour, how about the three great Vermont mountain courses Rutland, Barre and Brattleboro, which are all public? For a great example of the use of greenside mounds on relatively flat terrain, I keep coming back to East Mountain. Larry Gannon and Olde Salem Greens are great Boston area courses for the terrain Stiles enjoyed working with; lots of rolling movement for fairways and many slopes and hilltops for greens and tees. As is often the case, the hardest to get to offers the greatest rewards; three words make that clear: North Haven Island. Step off the boat and step back in time.

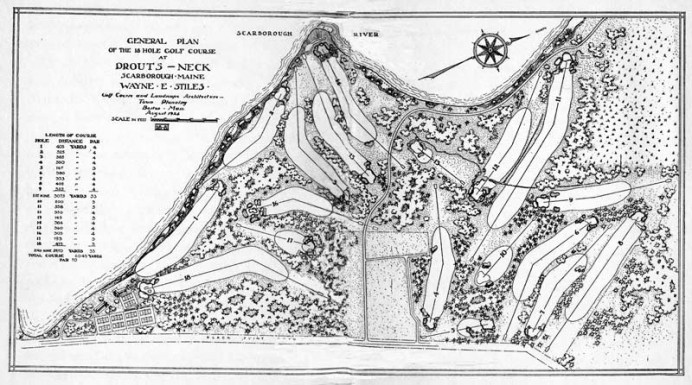

On the private side, Marshfield is one of the most intact, and given the excitement shown by the folks there over the old photos, I expect that course will continue to get closer still to restoring more great Stiles features. Norwood Hills is clearly in a league of its own, aside from being the only extant 36-holer, it is quite simply a magnificent Olmsted style park with two great golf courses winding through it. Just wandering the property and enjoying the trees is a great experience, and it minimizes the number of lost balls. Prouts Neck is also a virtually intact Stiles course and is his only true links design, so we’ll be putting up a few more photos.

The plan for Prouts Neck in Scarborough, ME is from the 1924 book entitled The Story of Prouts Neck.

BL: Study..schmuddy. The idea is to have fun not analyze. The easy answer is Taconic, Pine Brook and Prouts Neck â€three of his more sophisticated and cultivated courses. For people who appreciate originality and courses untouched by big budgets, and, who may in fact, play with hickory clubs as the courses should be played I’d go to Hooper in Walpole, NH, Rutland in Vermont and North Haven Island in Maine.

The course at North Haven Island, ME is accessible only by boat and is well worth the trip. The opening hole is seen above.

Please describe a favorite par three, par four and par five of theirs and why you admire each hole so much.

KM: Picking a favorite par three is relatively easy. Number 6 at North Haven Island. Not only is it a great short par three, but its setting offers the most of what I call the linger factor. It is the kind of whole where one can simply spend a few hours alternately enjoying the scenery and playing the hole. Considering how uncrowded the place usually is, that kind of experience in not unheard of. As for a favorite par four, I’d have to call it a toss up between numbers five, eleven and fourteen at Pine Brook. They all have the classic elevated green complex, the false fronts that reject all but the best played approach shots, and putting surfaces that make anything longer than about 2 feet a potentially serious challenge. Also, in over a decade of playing there, I’ve still only birdied 14, and that’s probably because most of the dogleg is gone along with the fairway bunker that used to be inside the elbow on that hole where a tree is now. I continue to lobby for putting back the fairway bunker. In the par five category, I like #11 at Marlborough because of the multiple bunker complexes, This hole is representative of Stiles’ use of both approach and greenside bunkers and makes for quite a challenge.

What course would most benefit from a proper restoration?

BL: I am a golf writer not a golf course architect. Asking me to recommend courses that should be restored is like asking an architect which of my articles should be rewritten. Stick to your own area of expertise; I defer to those with training in that field.

You most lament the passing of which Stiles course that no longer exists?

BL: I lament the passing of many of their courses, especially in locales where no courses replaced them for people to enjoy. We have few photos of two dozen Florida courses that vanished, and in a state starved for old, original Golden Age courses theirs would take a honored place among those that do still exist: Holly Hill in Davenport is probably tops on that list. One of the greatest regrets is Crawford Notch because it was in a stunning location, had giant features, we have multiple photos of its beauty, challenge and singularity. It made it to the 1970s before going out of existence.

Holly Hill is but one example of their lost work in Florida, a state all the poorer for squandering away so many fine Golden Age courses.

Of the Stiles & Van Kleek courses that you have seen, are there common themes in regards to how certain design features have been lost with time?

KM: As with so many classic era courses, bunkers have often been the first features to go, in landing zones, his prolific approach bunkers and of course the deep greenside traps. In many cases, hundreds of trees, especially conifers in the northeast, have been added which has changed not only playing strategies, but the agronomy in terms of changing soil characteristics, light and air movement. Fortunately we have records such as the Norwood Hills planting plan which shows us how familiar Stiles was with the long term growth characteristics of many types of trees and shrubs.

Is there a particular course that you would put forward as their most sophisticated design (i.e. where they poured in an unusual amount of time and thought)?

KM: That would be pure speculation, given that there are widely different types and amounts of surviving documentation from course to course. The answer would also depend upon the budget allocated for a particular project. Norwood Hills was a 45 hole project, literally five times the amount of golf holes planned for a large number of Stiles and Van Kleek project. In some cases such as Rutland, he was commissioned to do a large size color plan upon completion; in others, where we have little or no surviving plans, we simply don’t know how much the budget allowed for in terms of site visits, plans and other design work as well as oversight.

What is their boldest design? Taken as a collective set, what courses featured their wildest greens?

BL: I don’t consider any of their designs bold in the way that Charlie Macdonald’s designs are bold. They didn’t do grand. They didn’t isolate holes into their own arena. They didn’t add superfluous for the sake of magazine covers. They fit routings to existing sites and environments so they became part of the land forms. Wildest greens? Maybe Rutland because they’re all small, they’re all tilted, they were all designed to stimp around seven and now they run around ten for tournaments in August.

Are there misconceptions about their work that you would like to dispel?

BL: My guess is that there are only about a dozen people out there who have any conceptions about Stiles and Van Kleek courses, mis- or otherwise. But I would like to dispel one misconception about all courses: that golf has to be difficult to be good. Golf can be easy and be great at the same time.

What impact did Van Kleek have in South America? Are his courses still being played down there?

BL: When the partnership dissolved in 1931 due to financial problems John Van Kleek came to New York and worked for Robert Moses remodeling all the municipal courses in New York City. He directed hundreds of workers who would have otherwise been unemployed and updated a stable of courses that had been overplayed and under funded since their installation decades earlier. When that work was done he was called to South America by the wealthy oil companies that were beginning to export oil to the rest of the world. Van Kleek not only designed golf courses and imported playable turf grasses that would grow in the climates similar to Florida â€something they were previously without â€but also planned extensive communities for the wealthy executives of the companies. His reputation grew rapidly and his business expanded to include the estates of government leaders and the kings of the business world. Many of those courses, eventually converted to the finest private clubs of each country still exist.

Tell us about the Country Club of Barre in Vermont “ it sounds like a real gem.

BL: Country Club of Barre enjoys a fabulous natural setting so far out in the country that a vast majority of first time visitors get lost looking for it. It includes views of Camels Hump and the backbone of the Green Mountains. There isn’t a house visible from the entire course. Conventions are broken at every turn. There are two short par threes with elevated tees far above greens and neither is easy. There’s a par four of under 350 yards with a humpback fairway and deep woods on both sides and a blind green from 100 yards out. The Stiles holes are mixed in with other holes and it doesn’t matter which are which, it holds together as a fun and challenging play. If you need to know more I can recommend a great book that includes more than a thousand words about it.

Please summarize Stiles & Van Kleek’s lasting contribution to golf course architecture.

BL: They pleased their clients. They brought golf to locales that otherwise wouldn’t have it. They built courses everyone could have fun playing. They planned features that could be maintained with modest budgets. They gave other people credit when credit was due. They mentored. And they were good people.

KM: Bob summed it up pretty well.

The End