The Ocean Course at Kiawah Island

South Carolina, United States of America

The allure of playing golf through coastal dunes on a barrier island requires no explanation.

The Ocean Course at Kiawah Island is an incomparable playground, appreciated by golfers worldwide who cherish the elusive balance between challenge and the enrichment that comes from being cocooned in nature. Located along the Atlantic Ocean on the south eastern tip of a 10,000 acre sand barrier, the course always seemed destined for greatness. After all, on how many courses globally does the golfer enjoy the sound of the pounding surf on every hole? Yet, a great site doesn’t automatically yield a great course, especially with the added pressure that the course was to host the 1991 Ryder Cup a scant few months after opening!

Such pressure wasn’t new to Pete Dye. Already halfway into his peerless six decade career in 1989, he had become accustomed to the spotlight, including groundbreaking designs at Harbour Town in the late 1960s and TPC Sawgrass in the early 1980s. Regardless of the tight time schedule and even after the devastation wrecked by Hurricane Hugo, Pete and Alice Dye jumped at the chance to work on this tongue of property. The east coast of North America had not seen a site this good devoted solely to golf since Cape Breton Highlands in 1938.

Dye’s design associate Brain Curley picks up the narrative: ‘Landmark Land had purchased the property in the late 1980s. At the time, PGA West was under contract with the PGA of America to host the 1991 Ryder Cup. The PGA came to Landmark and wanted to move the event to the East Coast to gain a larger TV audience and to avoid the potential for excessive heat in the Desert in a September event. Landmark agreed to move the event to Kiawah Island and host on the new “Ocean Course”. If the course wasn’t ready, the nearby Tom Fazio course would serve as the back up. Pete, Lee Schmidt and I were there the day the deal closed for a site visit. We spent the day walking the fantastic site with its rich mixture of thick vegetation, dunes and scattered ponds. I remember that Pete was concerned about ticks and the Lyme disease which were in the news at the time. We went straight from there to the 1989 ASGCA meeting in Pinehurst and we were all incredibly energized by the environment and opportunity to route a course without any consideration for houses. The big challenge was where to place the clubhouse, given the large areas we had to avoid making any impact on. The course opened in time to stage the unbelievable Ryder Cup but it wasn’t until 15 years later that the clubhouse was allowed to be situated in its current, ideal spot with views out over the dunes to the ocean.’

Similar to Cruden Bay (which was a favorite of Dye’s) and North Berwick, the routing they devised is a loose figure ‘ 8,’ with several holes on each nine running along the dune line. Such a routing is infinitely preferable to the out-and-back layouts found in the United Kingdom and Dye later employed it again to great effect at Whistling Straits. The only potential drawback to such a configuration was that holes five through thirteen run broadly in the same east-west direction. However, long-time Head Golf Professional Stephen Youngner is quick to point out how Dye tweaked the angles of each hole so that the golfer is kept guessing as to the effect of the wind on his next shot. For example, though the sixth and seventh holes head in the same general westerly direction toward the clubhouse, the sixth fairway billows out to the right, calling for a draw off the tee. Meanwhile, the seventh doglegs right around an expansive sandy area with a power fade the ideal shot. The alternating ask of these two holes is but one example of how the wind effects shots wildly differently even if the playing corridors head in a similar direction. Indeed, only a handful of straight holes exist at Kiawah.

Can the golfer hit the power fade past the bunkers and reach the 7th in two?

Regarding the construction, Curley states, “Pete was given the directive from Joe Walser (one of the Landmark Heads) to see the ocean from tees, fairways and greens. After Hurricane Hugo decimated the region in September, 1989, Pete got to work. He moved a heap of sand to build up many of the playing areas and simultaneously, a massive re-vegetation effort was now going to be required after Hugo. The course incorporates all the usual angles of setup I had been accustomed to working with Pete but for the first time in my experience, Pete did a transitional edge look that was much more rugged. Huge, long tees were built rather than individual tees as he was very aware of the need for a ultra-flexible course set-up to deal with the strong winds. I remember him pointing out future tee locations that would stretch the course past 8,000 yards. Pete’s views in 1989 were way ahead of the curve.’

A prime benefit of moving so much sand was to create several tumbling fairways such as at the third, tenth, eleventh, twelfth, and sixteenth. The graceful sweep of these rolling fairways through the dunes is an element that separates the The Ocean Course from other Lowcountry courses. Closer to the greens, the land movement is tied into the surrounding dunesland and marshland areas. An inordinate amount of time was spent fussing about the green sites and getting them just right, a feat that is only accomplished when the architect spends as much time on site as the Dyes and crew did. Gone are the sharp edges present at some of his early 1980s such as PGA West or TPC at Sawgrass. Instead, the greens and the course enjoy a softer appearance consistent with its coastal setting.

As impressive as the course is above the ground, below the ground is equally so and explains why the environmentalists were kept happy during the construction process. Dye installed fourteen miles of underground pipes to create a unique internal drainage system that recycles the water from the course back into its own irrigation system. The normal pesticides and herbicides that are used in the up-keep are confined to the course; there is no runoff and thus the surrounding wetlands are fully protected.

Having been open only several months, the course was raw when it hosted the 1991 Ryder Cup and yet it produced one of the sport’s most enduring events, providing equal measures of heroic and humbling spectacles for all to witness. Critics admired the coastal setting but grumbled that it didn’t play like a fast running links. Built 45 minutes south of Charleston, this climate has no more chance of sustaining fescue fairways and greens than the author does of winning the 2021 PGA Championship to be held here! When it opened, The Ocean Course featured bermuda fairways and greens. Plenty of greens offer an opening for a run-up shot (e.g. the first, fourth, fifth, sixth, ninth, tenth, twelfth, thirteenth, fifteenth, sixteenth and the new eighteenth) but what caught the critics off-guard where the number of greens built on plateaus.

Professionals are often critical of features that don’t readily succumb to their skills but Dye had his marching orders and damn if he was going to let The Ocean Course prove an unsuitable host for the Ryder Cup. Some of the plateau greens (e.g. the ones at the second and eleventh) provide defense to reachable par 5s. Others like the third and eighth shore up short holes. The most infamous during the Ryder Cup turned out to be the one shot fourteenth, which proved to be invincible. This hole, which borrows Redan playing characteristics, lived up to that French meaning of being a part of a fortification.

As seen from behind, the raised 3rd green complex is bunkerless yet full of peril.

When downwind, plenty of approach shots land on the green only to trickle over. Indeed, Youngner contends that the pulpit green is even more wily when the hole is downwind. When the wind is against, balls better hold the plateau putting surface.

Having played here two months prior to the Ryder Cup, the author thought at the time that this was Dye’s finest design accomplishment. It was impossible not to be enthralled by so many standout original holes. Admittedly, the course would be a terror for stroke play; balls that hit on the young/firm playing surfaces could careen over and end up in a footprint in one of the sandscapes that surrounded a majority of the greens. What happened next though is where the story gets really interesting for the good amateur.

Let Green Keeper Jeff Stone speak of the course’s evolution over the next 20 years:

In 1997, Dye returned to The Ocean Course to make abundant, yet subtle, changes to the course aimed at both increasing the pace of play for the average resort player and adding additional challenges for the more accomplished player. The first change he made was replacing the turf on the approaches to each of the greens. For the Ryder Cup, the approaches were Tifdwarf Bermuda, the same grass that was on the greens. With Tifdwarf, if a player missed the green, their ball often ran off into the dunes or marshes. Even if the ball stayed in play, it left a difficult shot since most resort players don’t have a tight-lie flop shot. He changed the approaches to 419 Bermuda, the same type of grass that is on the fairways which is more “roll-resistant” and sets the ball up. This makes it easier for the average player to hold the green while, at the same time, makes it more difficult for the better player who would often bump and run chips (or even putt) up the slopes of the green collars. Forced to use a lob wedge, up-and-downs became much more difficult. He also added collection areas around many of the greens, greatly increasing the playability for the average resort player but, again, challenging the better player with uneven stances.

In the summer of 2002, he expanded the tee-shot landing area on No. 2 by ramping up the angle of the fairway and bulkheaded its second marsh crossing making it more visible. He added fairway to the left side of the tee-shot landing area on No. 4 and three pot bunkers to the right (turning the hole more left to right giving players a better angle into the green). He has also raised the tees and shifted them to the left as well as shaved down the fairway giving players a view of the marsh crossing on the far side of the landing area. On No. 18, he shifted the entire green complex out to the last dune near the Atlantic Ocean making one of the most dramatic finishing holes in golf. In addition to these architectural changes, new tees have been created on seven holes and a number of the existing tees have been enlarged. From a visual standpoint, other than the 4th fairway and the 18th green, most players wouldn’t know these changes were made. From a playability standpoint, however, these subtle changes make a big difference.

In the summer of 2003, he resurfaced every green with Paspalum specifically designed for The Ocean Course’s seaside environment. In fact, it is named for The Ocean Course – OC03. In addition to a blade size comparable to Tifdwarf, it can be mowed to the length of 1/10 of an inch providing the necessary green speeds demanded by today’s professional tournament venues. Plus, unlike Bermuda grasses, there is virtually no grain and the grass comes in thick to give the greens a sense of maturity even when the greens are relatively new. Additionally, he substantially altered the fairway bunkering on No. 9, No. 11, No. 13, No, 16 and No. 18, reclaiming the course’s original bunker lines that changed over the years with the sifting dunes. These changes both make the holes more playable for the average resort player and tempt the better player to take additional risks.

As noted above, this course was always going to shift around as it was built on sand. The implementation of more grass around the greens as well as more grass-faced bunkers helped produce fewer bad lies while multiplying the number of fiddly chips from short grass around the greens. This was a win-win: Pace of play improved while the course’s short game interest was significantly enhanced.

The moniker ‘War by the Shore’ conveyed a sense of going to battle in 1991 but by the time the course hosted the 2012 PGA Championship, the course was altogether a more fun – and varied – test. For the 2021 PGA Championship, a new tee has been added to the sixth which can push that two shotter over 500 yards but otherwise, little else was required. When it opened, the course already had the potential to play from 7,800 yards, though the Ryder Cup played it 700 yards shorter than that. The flexibility that Dye gave the course from the start has served it well.

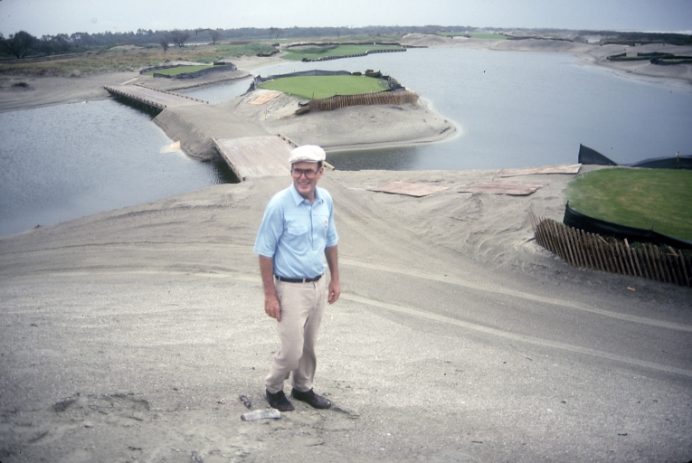

Pete Dye, in the field, making it happen.

Like Pinehurst No. 2, The Ocean Course is the best of both worlds: It could host a tournament with a mere two weeks notice but in the meanwhile, it provides the stage for what may be the resort guest’s most memorable round of the year. Two distances are given below, one from approximately where the Ryder Cup was played and one from the Dye set, which measures 6,475 yards and is from where countless people enjoy the course, even if the wind gusts. As with all Dye courses, there are plenty of tees to pick from and anyone who complains that the course is ‘unfair’ is simply playing from the wrong set given the day’s conditions.

Holes to Note

First hole, 395/365 yards; Dye eases the golfer into the round with lots of room off the tee and a green with a bail-out area left. Though it is the farthest hole from the ocean, the dull roar of the surf is still heard, which hints at how special the round is likely to be.

The 1st hole slowly reveals itself on approach from the practice area.

With plenty of room left of the green, the modest length 1st is indeed ‘a gentle handshake’ opener.

The different hues and textures captivate in this view back down the 1st in the early morning light.

Second hole, 545/500 yards: One of the game’s most complex three shotters, this double dogleg reminds the author of boxer Joe Lewis’s famous one liner: ‘Everyone has a plan until they’ve been hit.’ Care must be taken with each shot. The tee shot and second must negotiate the wetlands while the third is to a raised green that is defended by a pit on the left and more marsh on the right and beyond. A testament to its difficulty is that Seve Ballesteros won the hole with a 7 to Wayne Levi’s 8 in the singles matches in the final day of the 1991 Ryder Cup. Curley succinctly sums up one of the The Ocean Course’s challenges: ‘It has the toughest second shot par 5 lay-ups of any course that I have ever seen.’

One of the game’s great diagonal carries comes at the 2nd where a long hitter might elect a line 90 yards left (!) of a short knocker.

The live oaks lend the course a sense of maturity far beyond its 30 years.

The brave man who carries past these steps on the inside of the dogleg has the chance to reach in two.

This marshland cross hazard bisects the fairway 115 yards from the green. If the golfer can carry it in two, he gains the preferred angle into the long and narrow green.

This man boldly went for the green in two but the green’s defenses thwarted the desired birdie.

Third hole, 390/320 yards; Yet another example of why Dye was the modern master of holes under 400 yards. The fairway itself is plenty wide but as befits a hole of this length, the small 3,920 square foot green may be the course’s most elusive target. The plateau green is relatively flat, which means that it offers little help in stopping the player’s approach shot vis-à-vis a standard green that tilts from back to front. On calm days, if the flag is front left, the golfer should opt to play his tee shot wide right. If the hole location is back right, the better angle is from the left side of the fairway and at a generous fifty yards in width, the fairway provides these very options. Of course, with time, the golfer may also conclude that hitting for the middle of the green and putting out to the various hole locations is the prudent move!

Why aren’t more green complexes built like this?! Even in no wind and a tame putting surface, the player has his hands full.

The putting surface is the least of your worries.

Fourth hole, 455/400 yards; Once too awkward to be considered great, Dye improved it in 2003 when he was granted the ability to enlarge the fairway to the left. The golfer now has a realistic chance of seeking a good angle of approach. Still, the right to left crosswind complicates the approach into this left to right angled green. As the aerial below suggests, what an appealing yet challenging canvas with which to work! Tucked into the base of a dune, the green site is one of the most natural on the course.

This aerial shows the desire for drawing the tee ball left off the central bunkers and then fading the approach into the angled green. Asking the golfer to shape the ball both ways on one hole was a favorite Dye design ploy.

Fifth hole, 190/165 yards; The variety of the green complexes at The Ocean Course is already evident: the convoluted second green, the flat perched knob at three, the angled front left to back right fourth that nestles into the dunescape, and now the large right front to back left diagonal green here. Similar in configuration to the seventeenth at Pebble Beach, this hour-glass shaped green is divided by a ridge in the middle. The difference in a front right hole location and a back left one is as many as four clubs on this 55 yard deep green.

This 1990 photograph shows just how fragile the course was to wind events and how plantings were used to stabilize the sandy environs.

Plenty of short grass and safety off to the right but the more accomplished player needs to flirt with the hazard to achieve a desirable result. Photograph courtesy of the PGA of America.

Greens like this one lend The Ocean Course great flexibility in its day-to-day set-up. On consecutive days in 2006, the author hit a 8 iron to a downwind front hole location and a 19 degree hybrid the next morning to a back hole location when the hole was into a club wind. That’s a 6 club difference in the span of 18 hours with the hole equally engaging – though completely different – under both circumstances.

Sixth hole, 455/345 yards; A microcosm for the entire course, this S shaped fairway provides all sorts of possibilities and playing angles depending on the day. Absent is anything linear or harsh to the eye with the end result being a hole of great adaptability.

As seen from behind, this front hole location is best attacked from the left portion of the fairway. Move the hole back and left, and the golfer needs to play to the outside of the fairway with his tee ball. Photo courtesy of the PGA of America.

Seventh hole, 530/495 yards; A proper dogleg, the golfer is tempted to gain an advantage by successfully challenging the hazard on the inside of the dogleg. In this case, his reward is a crack at the green in two. Of course, Dye defends par at the green, which possesses a neat lower right quadrant. Lost in the shuffle is likely to be an appreciation of the distinctive XXX trees that lend the hole such a handsome backdrop.

The 7th green seems innocuous this far back and it readily accepts a running approach that scoots onto the green front left. Meanwhile, looks can be deceiving as we see below as …

… the green’s right front is much more elevated from its surrounds than the golfer can discern back in the fairway.

Eighth hole, 195/165 yards; The Reverse Redan characteristics of its green make the eighth one of the course’s sleeper holes. Just short on this built-up green and the approach rolls back to the green’s base. Carry into the middle of the green and the approach will often track toward the back hole locations, encouraged as it is by the high left front to lower back right step in the green. This green is joined by the seventh, thirteenth and fourteenth putting surfaces for having a lower back quadrant and the player talented enough to flatten out his shots can use such contours to his advantage.

The point can’t be stressed enough how the golfer is encased in nature throughout the round. Wetlands give way to dunes and then the ocean left of the 8th tee.

Though seemingly straightforward, the 8th isn’t. The golfer sees the four foot bank that leads up to the putting surface which in turn is angled and steps down and to the right.

Long is no good; Note the “Danger Alligator” sign!

Ninth hole, 465/405 yards; The ninth is a sharp dogleg left, which again dispels the knock that a ‘figure 8’ routing means a long slog in one direction. Refinements took place in 2003 and in particular, the golfer now sees the flag from the tee, wooing him left and perhaps into taking too ambitious a line off the tee.

This fierce bunker complex admirably defends the inside of the dogleg’s integrity. Its vertical walls almost guarantee the addition of one stroke.

Tenth hole, 440/370 yards; The back nine is a series of arresting holes that are made exceptional by the never ending use of interesting angles. At the tenth, a daunting sand pit must be carried from the tee to gain the best angle into the green, which is open front right.

The golfer willing to make the long carry right is amply rewarded with an ideal angle into the green.

Paspalum has proven to the ideal playing surface for the South Carolina climate. The greens feature fine contours with nothing overwrought or contrived. Other modern courses rely heavily on green speeds to keep the best players at bay; there is no such need for that at The Ocean Course, a testament to how well balanced the overall test is.

Eleventh hole, 560/505 yards; An easy way to lend a three shotter teeth is an elevated green site. Should the player gets off track on one of his first two shots, the target becomes increasingly difficult to hit with anything other than a short iron. Additionally, the tiger who is trying to reach in two has his hands full as well. Such is the case here, and some of the thickest sea grasses surround the left and back of the green, so the miss is short and/or right. A great swing hole where anything from a 3 to an 8 is possible. Look for this half par hole to play a key role in determining the 2021 PGA Champion.

As we saw at the last hole, when Dye built fairways up to provide views of the ocean, that also meant that he could build fairway bunkers down, which we again encounter here off the 11th tee.

Though reachable in two, good luck holding the knob green with anything other than a short iron.

A fine place to play one’s third shot is from the right half of the fairway where the golfer is afforded the best view of the putting surface.

Twelfth hole, 465/410 yards; This and fifteen are the only two holes on this side where an uninterrupted, straight line can be draw from the tee to the green. Such is a common occurrence at plenty of courses but not here. Yet, the occasional straight playing corridor on a course with fairways that twist and turn actually adds variety. On one of his last visits here, Dye mused about the possibility of playing it from ~400 yards as a potential drivable par 4 when downwind. As the fairway cascades downhill the last 150 yards, it is a more reasonable proposition than one may suspect! The hitch is that the fairway progressively narrows and that a canal rubs up close to the fairway for the last 75 yards before the green. Anything that bleeds right is likely gone and that includes if the hole is played from its standard length, leaving the golfer with a tricky downhill approach that invariably produces a ball that drifts right. Greenside, humps and hollows help ensure that a player who tentatively plays away from the water will face a ticklish up and down.

This aerial, courtesy of the PGA of America, highlights the complicating factors for one’s approach at 12.

This view from 100 yards highlights why the 12th is the lowest handicap hole on the side.

The Ocean Course is a walker’s dream, helped by tight green to tee walks everywhere save from 9 to 10. After holing out at 12, the golfer takes this bridge to the 13 tee, from where he confronts a wonderful diagonal tee ball.

Thirteenth hole, 405/365 yards; An all-time favorite of Dye’s and a favorite of resort guests for three decades, this classic Cape swings right along the marsh. Options abound off the tee, depending on how aggressive a line the player wants to take relative to the marsh right and a cluster of bunkers left. There is no pat answer and even if there was, it changes with the shift of winds from morning to afternoon. The long green is 41 paces deep, narrows in the back but is open in the front and at grade with the fairway. A low runner is always a consideration. This hole’s flexibility hinges on the green being open in front and this hole can play anywhere from 350 yards to 470 yards while still preserving the angles of play.

Angles, angles, angles – the appeal of the 13th endures forever, regardless of advancements in technology.

A series of bunkers punctuate the fairway from the left. Getting past them from the tee is imperative as this shot from 195 yards is wholly unappealing!

The only advantage from hugging the canal off the tee is that one then gets to aim his approach away from it. Having said that, …

…this view from the left center of the fairway seems far preferable!

The green falls away to the rear, so let the putting surface do the work when the hole is in the back third.

Fourteenth hole, 195/160 yards; The saying at Rye Golf Club applies to this modified Redan: the key shot is the second one! One of the challenges is that this is the first time that the golfer hits a ball in a southeasterly direction in ~two and half hours (i.e. since the tee shot on four) as this one shotter starts the five hole journey east back to the clubhouse. Therefore, getting an accurate read on the wind is problematic, exacerbated by the built-up green pad. Perhaps the consolation of the bracing view of the ocean can temporarily assuage the golfing concerns? The real kicker is the putting surface itself, which rises from the front to the middle, before bending left and dropping down two feet to the back edge. Hitting the green from the tee is good but hitting and holding the green from the tee is truly impressive. Dye’s architecture gets at the purity of the strike, which can be upsetting to plenty of players. The PGA will use the 235 yard tees for at least a few rounds in 2021 and you can count on this hole to agitate and perturb. Indeed, Dye considered it his duty as an architect to get under the player’s skin and mess with his comfort zone. This pushed-up green complex does so with grace in a most magical setting.

The one shot 14th green complex slopes away on all sides and possesses Redan characteristics. It proved to be most vexing during the Ryder Cup matches and will no doubt prove so again for the 2021 PGA Championship. Photograph courtesy of the PGA of America.

Fifteenth hole, 420/380 yards; To gain perspective on how good The Ocean Course is from top to bottom, pick its three weakest (or perhaps ‘least distinguished’ is more apt) holes. For some, that would include the fifteenth. Now let’s think about that. First, the hole parallels the Atlantic Ocean. Second, the preferred tee ball is toward the dune line on the right because a large bunker runs left down the entire hole, jutting into the fairway before then hugging the left side of the green. Third, the green houses some of the more pronounced contours on the course. Well! While the fifteenth may not be the first hole that one thinks of regarding The Ocean Course, it would be the highlight of most courses elsewhere.

Traditionalists appreciate that seaside golf shouldn’t offer perfect optics with everything laid out neatly before the player. The view from the 15th tee contains mystery and the player is unlikely to see where his tee ball finishes, both laudable attributes.

This 2004 photograph shows the sand sweeping up the bunker face, which ultimately proved to be an unwinnable chore to maintain properly. Today’s greenside bunker …

… is grass faced and deeper.

As seen from behind, the intermediate sized 15th green is best approached from the right side of the fairway. Photo courtesy of the PGA of America.

Sixteenth hole, 580/540 yards; This hole’s elasticity captures part of the course’s appeal. One day, the author hit a driver, three wood, one iron and barely reached the green in regulation. The next day he was over the back with a driver and three wood! In either wind, the hole plays equally well and Dye deserves heaps of credit for building such flexibility into many of the holes. Such an example of the ever changing playing conditions is but one reason why coastal courses must be considered supreme to inland courses. The fairway is massive in width but only by staying on the higher, right side will the golfer a) gain a clear view for his second shot and b) enjoy the best angle into the green should the hole be downwind. A fine example of how Dye makes a hole playable for all yet exacting for the better golfer. The scale of the hazards sometimes dwarf the golfer, such as here where this ten foot deep greenside bunker keeps the golfer honest in how he plays the hole. How refreshing to find a three shotter that stands up to the advances of technology and it caps off a sensational set of three shot holes.

The tiger needs to position his tee ball close to the large fairway bunker in order to enjoy the best chance of hitting – and holding – the angled green in two. Langer’s clutch up-and-down from the greenside bunker in the 1991 Ryder helped propel his match to the final hole. Photo courtesy of PGA of America.

Seventeenth hole, 220/180 yards; At the Battle of Ypres, Sir John French noted, ‘It slowly dawned on me that they were using heavier artillery than we were.’ Many golfers share a similar feeling when they stand on this tee. Though the author prefers the fourteenth because of how it embraces the coastal environment, there is no denying that this is the course’s most well known hole to television viewers. Indeed, name a side with a tougher pair of one shotters than the second nine here?! Relative to the fourteenth which plays at an oblique angle toward the ocean, this one plays at a 30 degree angle away from the shoreline, the only hole on the course to do so. Just when the pressure is the greatest, questions swirl in the golfer’s mind in terms of wind direction, etc.

A nail biter of a forced carry, especially when the wind is about. The best ‘misses’ are (of course) dry which suggests either left or long over the green.

Each tee marker is progressively left and eventually, the forced carry dissipates from the red tee. Thanks in no small part to his wife, Dye always built a sub-5,500 yard set of tees.

Eighteenth hole, 440/400 yards; Not many courses can claim two of Dye’s finest finishing holes! Originally, Dye was forced to stay clear of the dune line so he nestled the green forty yards inland among some manufactured dunes. This is the green site where the Langer/Irwin Ryder Cup match reached its epic final crescendo. In 2002, working closely with the Environmental Protection Agency, the Resort gained permission for Dye to move the green site to where Dye had always wanted it: 30 yards to the right along the main dune line, leaving the ocean as the backdrop for the day’s final approach. Though the original green site is no more, both of these finishing holes could be considered among Dye’s best as they are/were both natural and restrained, unlike some of his built-for-television finishers elsewhere.

The clubhouse was relocated to this position in 2006 and its veranda is the perfect spot to reflect on your round while viewing the action up the Home hole.

This view back down the Home hole shows how a fade is preferred from the tee while a draw is ideal for one’s approach. The plethora of playing angles throughout the round certainly favor the shotmaker. Photo courtesy of the PGA of America.

As a raw site, this was arguably Dye’s single greatest opportunity in his long career. Though the immediacy of the rocky shoreline at the Teeth of the Dog was utilized to great effect, its inland holes lack the same interest as those at The Ocean Course. Ultimately, when one couples the appealing nature of the golf with the glorious Carolina coastal setting, one may conclude that The Ocean Course is indeed Dye’s finest course. The author would steadfastly select its second, third, eleventh, and thirteenth holes and potentially its twelfth, fourteenth and sixteenth for inclusion in Dye’s best eclectic all-time course. Bottom line: The course is simply chock full of first rate holes and to the author at least, the back nine is Dye’s finest nine holes.

Others disagree. Some people’s judgement remains clouded by the Ryder Cup where the public witnessed the professionals being humbled. Without a doubt, the course hosted the Ryder Cup matches one year prematurely and that shaped its early reputation for being a brute. It certainly can be, however, since then, the new owners of Kiawah worked hand-in-hand with Dye to soften any over-the-top requirements while making the course much more user friendly on a regular basis. Much of Dye’s fine-tuning was accomplished between 1994 and 1997 when Kiawah hosted the International Team Championships. After Scotland won the event at 31 under par (!), it was evident to all that the course had become more enjoyable to play than in 1991. Colin Montgomerie went so far as to say during the closing ceremonies that ‘In 1991, the course was unplayable, but now it’s grown into one of the world’s finest, if not America’s best resort.’

A critical step in the course’s evolution occurred when five acres of turf was brought in to grass many of the recovery areas around the greens. Long gone are the days where the ball rolled off the back of a green and into a foot print. Recovery shots are both more manageable and varied to the point where some critics now consider these green complexes to be Dye’s finest. The rotating asks between the greens that are at fairway level and the ones that are on knobs or plateaus are first rate. Also, a new irrigation system was installed that provides coverage of some of the sandy areas. The Club has the capability to water such areas and prevent the sand from blowing across the fairways and greens during windy conditions. The course has never been in finer condition than in the summer of 2020.

Nonetheless, some people play the course today to say that they have tackled ‘The Monster.’ This is ridiculous. Like every Dye course, there is a set of tees to accommodate even the modest golfer. And many of the fairways are ~30% wider than on traditional inland courses. Sure, in a strong wind, the course bears its teeth but so does Pebble Beach and no one grouses there. Dye gives the golfer plenty of room to play and only when the golfer stops thinking and starts trying to force shots will he remember those famous words from the Battle of Ypres.

The Ocean Course doesn’t reveal all her secrets after just a few rounds. However, if the golfer takes the time to know it as it exists today, one thing is for certain: you will play a round there that you will remember the rest of your life, long after all the other pretender courses are distant memories.