White Bear Yacht Club

Minnesota, United States of America

What defines a great course? Its greens, where you likely take a third or more of your shots? How about the fairways, where the majority of a round is spent? Hard to say. First, most architects don’t build great greens. Second, sites blessed with interesting land well-suited for golf are few and far between. Third, even on an ideal site, the architect must route consecutive holes so that the landforms are captured in a meaningful manner. On the rare occasion when these hurdles are overcome, you are in the presence of a truly remarkable course. Welcome to White Bear Yacht Club.

Like so many great clubs (e.g. Pine Valley, Augusta National, etc.) the drive to the club gives little away. The word ‘yacht’ portends a romance that comes from a large body of water (we are in the Land of Lakes) and as you wind your way toward the clubhouse, glimpses of White Bear lake are afforded through the trees. Yet, the road is flat and the golfer’s expectations are held in check. As you arrive, the main clubhouse becomes visible, high on a hillock to the right with the lake below. The first time golfer is impressed but there is no sense as to where the golf is until he learns that the building on the other side of the road is the Golf House and that the land around it is luscious and heaving.

Which architect from the Golden Age was given the opportunity to work with this special land? Well … that is indeed a fine question! Club member and historian, Mark Mammel, has been gathering information and mulling over that very question since 1992. His conclusion:

All sources agree that William Watson created an original plan. The first 9 holes, which opened in 1912, may have followed this plan, but this is also uncertain. The course was on a 45 acre plot north of the clubhouse and other than perhaps #17, no holes from this layout still exist. Minneapolis Tribune golf columnist George Rhame, in Sept 1913, stated “The White Bear course, a 9 hole invention, has no bunkers nor does it need any.” The 18 hole course, which opened in 1915 had many bunkers throughout as shown in a large contemporaneous surveyors map. In “Golfer’s Magazine” from May 1925 past Commodore W. G. Graves describes that the early 9 hole course “came into being” but adds no other details, then states that after acquiring more land “… an 18 hole course was planned. William Watson laid it out. Donald Ross gave freely of his advice in its development and Tom Vardon, the professional at the club, was of great assistance.”

That seems simple enough: ‘William Watson laid it out. Donald Ross gave freely of his advice in its development and Tom Vardon, the professional at the club, was of great assistance.’

Alas, Mammel continues:

There are some problems with this description. In the 1961 club history (which is mostly about sailing) member Margaret MacLaren is quoted: “On a Sunday noon, the summer of 1910, she [Mrs John G Ordway] was lunching at the home of her father-in-law, Lucius P. Ordway, at Dellwood. Among the guests were William Mitchell, Henry Schurmeier, and Donald Ross, a very well-known golf course architect. These gentlemen were discussing plans for a 9 hole course for the White Bear Yacht Club.” In a previous iteration of this discussion on the GCA site Tom MacWood stated that he had Ross’s travel records for 1910 indicated that he was in the UK the entire summer. However, even with this caveat, I can see no reason why Mrs. MacLaren would create this story out of whole cloth, since neither she nor anyone at the club really cared one way or another who the designer might have been. Could she have had the wrong date? I suspect so. Additionally, since the golf course opened in Fall 1915 and Vardon didn’t arrive until 1916, it’s difficult to see how he could have influenced the original layout. Brad Klein in his book places Ross at WBYC in both 1912 and 1915. An article from the Minneapolis Morning Tribune from Sept 1916 states that Ross was going to WBYC “with a view of rearranging it.”

Mammel concludes:

So where does this leave us? As I keep going over it all, I suspect the routing is from Watson. It is interesting that 2 prominent Minnesota Ross courses, Interlachen and Minikahda, were also originally laid out by Watson! Ross clearly was involved around the time the 18 holes were being built, as he was active in the Twin Cities with Woodhill and Minikahda at the same time. How much credit should he get? He doesn’t name the course in the list his company published, though he does name Minikahda, Interlachen Woodhill and Northland in Minnesota. Vardon probably worked with bunkering, since many of the bunkers from the 1915 map, as shown from a later aerial photo, no longer exist. Vardon was a well-known regional course designer so it is no stretch to imagine he had opinions and input as the course matured during his tenure as pro (1916-1937). The club has been accepted as a Ross course by many, including Brad Klein and the Donald Ross Society. Tom Doak indicated that many features fit with Ross’s style, though he made it clear he had no real evidence of this provenance. Jim Urbina is on the same page, recognizing the course as a great classic layout no matter whose name is attached.

That’s a perfect summation: ‘a classic layout no matter whose name is attached.’ Clearly, Watson, Ross and to a lesser degree Vardon were all ‘chefs in the kitchen’ but like a person dining, what matters is the food on the plate in front of him as opposed to who did what in the kitchen.

Though its provenance is unclear, the course’s maturation has been peaceful with the club demonstrating the rare wisdom of leaving well enough alone. As noted by Mammel, Commodore W. G. Graves’ beautifully worded article in 1925 also read in part, ‘ The original plan tested by play has required very little change or modification. Such changes and improvements as have been made as opportunity afforded have been strictly in line with the plan after experience showed that nothing more was needed. There has been no vacillation and there is no regret for money ill spent and for unnecessary discomfort and interruption to play.’ This same kind of no-nonsense approach has carried on decade after decade with mercifully few blips along the way.

In the 1980s, a local architect did some work to a few holes including the seventh, eighth and sixteenth. Bunkers were added to ‘defend’ two short par 5s and the one shot eighth hole was notably modified. In 1993 the club contacted Renaissance Golf Design in Michigan and charged them with restoring the eighth hole as best they could from available aerials. Tom Doak and Jim Urbina paid a visit and brought down the hillside into the green complex and restored the original bunker pattern. Once again, a tucked back right hole location is something to behold. Both architects were smitten by the land and course.

Urbina’s distinct recollection from his initial trip twenty-six years ago was that the course possessed some of the game’s most unique landforms but that they were masked under a canopy of trees which hid the scale of the property. He hoped for an opportunity to return. Eight years later, the club decided to address the modernized bunkers around seven and sixteen. Urbina cleaned up those holes and as he prowled around the rest of the property, he began formulating a vision for a better tree policy and mow lines with Green Keeper John Steiner, who is an institution in Minnesota. Steiner has manned the position since 1979 (!), first having caddied there in 1969 and then joining the green keeping staff the following year. Urbina knew that they would become friends after discovering Steiner’s original copy of George Thomas’s cornerstone book on architecture, Golf Architecture in America, sandwiched between books on agronomy.

The same story that played out at hundreds of Golden Age designs across North America was also true at White Bear Yacht Club: Tree growth had altered the width of the playing corridors and hindered proper turf quality. By 2012, Urbina, now under his own shingle at Jim Urbina Golf Design, worked with Steiner to re-present the mow lines. Fairways were extended and re-connected to the fairway bunkers. Short grass was instituted around many of the greens including the ninth, twelfth and fifteenth holes. All the work was done in-house and by 2015 the focus was expanded to restoring vistas like the sight of the third green as one approaches the second green.

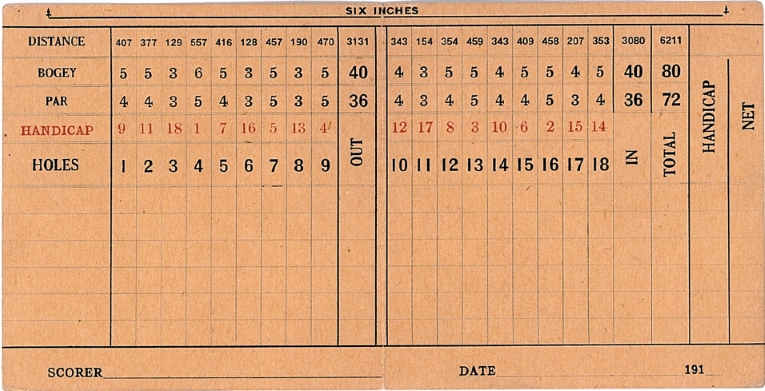

Today’s course plays to a standard par of 72, measures nearly 6,500 yards, and the nines return to the Golf House. Given that the land is so singular, there are peculiarities. There are five one shot holes and five three shot holes. You encounter a par five within every four hole stretch and four of the first eleven holes are one shotters. What the three shotters give, the one shotters take away! The course is not heavily bunkered – only 62 and there is an appealing dearth of greenside bunkers around the five par 5s. Those five holes combined total but two and both par five greens on the second nine are bunkerless, the ultimate compliment to the land. Interestingly enough, two of the one shotters (six and eleven) combine for 20% of the course’s bunkers and the twelfth hole alone accounts for nearly another 20%.

From the author’s perspective the two standout features are how the holes lay on the ground and the variety of the putting surfaces which are every bit the equal of the terrific tee to green land movement. Having spent considerable time on site, Urbina unhesitatingly places it in his top 10 in terms of topography and green locations and notes that the course ‘…reminds me of Eastward Ho! on Cape Cod in that the excitement never stops.’ In fact, Urbina thinks that it rivals any course in the Midwest, which, when you consider the golf rich states included, is high praise indeed.

Keep an eye out for the attractive greenside mounding as we tour the course below. It comes in all shapes and sizes, from a massive knob in front of the first green to the low-lying, long hump that stretches along the right of the third green. Their irregular appearance speaks as to handwork versus machine work and stamps the course as built during the Golden Age. Having only played a couple of Watson courses, the author was curious if such mounding was indicative of Watson’s work, so I contacted Green Keeper Josh Smith at Orinda Country Club. Watson laid out that charming course in the foothills northeast of San Francisco in 1924. Smith’s response is telling: ‘Yes, Watson used mounds to accent holes here. I am also particularly impressed by his routing up and down and around the hills and how he handled the creek crossings. We are in a hilly neighborhood but he created a very nice walk with no two holes alike. Additionally, he clearly cared about the variety of the 3’s and purposefully built a short one with teeth. Lastly, he appeared satisfied with minimal overall bunkering, especially in the fairways.’ As we will see, those words (save for the creek crossings) apply equally well to White Bear.

Holes to Note

First hole; 405 yards; Ross wrote of a gentle handshake, which tells you straightaway that Watson routed this beast! Standing high on the tee with Golf House directly behind, there are countless ways to get the round off to an ignominious start. If by chance the player hits a fine tee ball, he now faces an approach that could rightfully be described as potentially the most ruinous on the course. The green is a good twenty feet above the fairway, on top of a daunting embankment. A knob in front of the green obscures the putting surface, even from the right side of the fairway. At its base, the course’s single deepest bunker awaits and given that you are hitting your approach from an uneven lie, the bunker receives plenty of grumpy customers. The land makes the hole, the solitary bunker helps define the playing strategy, and the green is full of personality. In short, it neatly forecasts what is to come. If there are ten better opening holes in golf, the author hasn’t seen them.

The inspired view from the 1st tee captures the excitement that is to follow. Strategically, the right side opens up the green and removes the pit from play but … out of bounds lurks right of the trees.

One of the charming features that dates the course as pre-1920 are rises fronting several of the greens. This one is the most pronounced but the 5th and 7th greens possess a similar feature that muddles the optics for one’s approach. By the 1920s, architects had largely abandoned this construct and that is one of the reasons that an argument can be made that courses built in the 1910s are more character-filled.

Second hole, 430 yards; What does land movement mean to a fairway? Several things. The more interesting the movement, the more discernible the hole is from its peers as it is given its own unique voice. Second, a fairway with movement means that it matters a great deal where one’s tee ball lands. Hitting on a downslope versus an upslope translates to an approach several clubs shorter. Third, fairway movement defines daily play as, alas, it is always there, day-in, day-out. It isn’t part of the playing corridor like a bunker – it is the the vast majority of the playing corridor. Fourth, and this is why links golf reigns supreme, a lumpy fairway makes a golfer continually make minor tweaks to his stance/set-up. In so doing, a course with such fairways becomes infinitely more interesting to play than one with flat fairways, especially for the 50th and even 500th time. Is the author implying that White Bear Yacht Club approaches the ideal member’s course? Absolutely.

The speed-slot off the second tee is down the right and leaves this approach shot from a hanging lie. Note the attractive mounding that accents the green.

This 2017 photograph from behind shows how the fairway was widened to the right by 4 to 5 paces. An enhanced appreciation for the course’s property comes from watching balls release along the short grass rather than being constrained by rough.

Third hole, 135 yards; To define what makes a ‘great set of greens’ is to delve into how eighteen putting surfaces both complement one another and pose different questions. Put another way, the fourteenth green at Augusta National is undeniably magnificent but six of them in one round would not constitute a great set. White Bear Yacht Club runs the full gamut from small to large greens, sloped front to back and back to front, wild interior contours and greens with more tilt than contour. The third green is of the small variety with a deceptive cant from front right to back left. It sits perfectly atop a ridge. While prudence suggests hitting for the middle of the green and putting out to perimeter hole locations, the hole’s diminutive length prompts greed. A golfer who chases after left hole locations and hits a pull feels like a numpty.

The beautifully situated 3rd green. Standing on the tee higher and to the right, the flag is always visible but the hole/cup itself is obscured 1/3 of the time by a ridge in front, signifying what Watson thought was – and wasn’t – important.

The bunker in the foreground is an intriguing feature, as it is 4 feet above the putting surface and snares the slightest under hit tee ball.

The putting surface is none too big but is a good one to find off the tee. Though a pull off the tee feels calamitous, you will quickly find your ball and a deft recovery is possible, if unlikely. Like all great courses, you shouldn’t lose many balls over a playing season, though you will find yourself in a slew of awkward and/or entertaining positions.

Fifth hole, 440 yards; Cries of ‘unfair’ would ring loud if this hole was built today, which is always a good sign that you are about to tackle a hole with unconventional demands. There’s no mollycoddling on this brute. The tee shot is manageable (play to the right) but the long second is to a green that is cruelly unhelpful. Expertly situated in a saddle between slight rises in front and back, the putting surface is low in the middle and drifts downhill to the right. If the golfer wants a friend, he will need to get a dog. Similar to the equally unjust Road Hole on The Old Course at St. Andrews, the vast majority of the 4s registered here come by virtue of a one putt – and a ‘4’ feels like a hard fought birdie.

The biggest hills are down the left so to find the ‘speed slot’, pound one right and hope that the hills don’t retard its run too much. Of course, similar to the 1st and 2nd tee balls, the vague threat of out-of-bounds right hinders a free-flowing swing on the tee.

Sixth hole, 150 yards; How an architect follows a murderously difficult hole like the fifth is telling. If he backs it up with another toughie, the member can feel bruised and battered, or even dispirited. If he follows it up with a hole (or two) that tempt, the member is encouraged and stays wholly engaged. Combined with the half par, uphill seventh, the golfer has a real chance to rebuild from the damage invariably inflicted at the fifth.

… seven bunkers ring the 6th green. As they are pulled back from the putting surface, they tend to leave an awkward length recovery shot. Like the 3rd, the golfer does himself a service by hitting the green in regulation and not fussing about.

Ninth hole, 515 yards; Normally, the author isn’t a fan of elevated tee boxes as they tend to flatten a hole’s appearance and rob the golfer of a sense of the land’s movement. This proves to be an exception where the closest tee to the prior green is – no surprise – the original tee, which was to the right and uphill from the eighth green. A new tee was added in the 1990s behind the eighth green to give the hole an extra ~30 yards and make it less vulnerable to technology but the new prospective from a lower angle is less invigorating. From the original tee, on the high spot on the property, the golfer can’t but be impressed by the scale of the ‘rolling waves’ of hills before him. One hopes to carry a hill some 230 yards out and have one’s tee ball carom forward another 30 to 40 yards. Then, the green, hidden from the player down in the valley, can be reached with a mid-iron, assuming the wind isn’t coming off White Bear lake. It is the kind of wildly irritating hole that can get under a good player’s skin if he doesn’t play it in four shots. Making such a score more tenuous is the angled green, the course’s second smallest target and its soft shoulders make it particularly elusive. Short grass now encases the green and the run-offs lead to a far more fiddly recovery shots than before.

The view from the original 1915 tee highlights the turbulent topography with the 9th hole ending in front of the Golf House. As an example of the continual progress being made, the fairway now extends to the bunker on the left, a good five paces wider than seen in the 2017 photograph above.

Tenth hole, 330 yards; Both Ross and Watson were masters of routing two shot holes that played from a high tee into a valley and up again to a high green, which is what we have here. Indicative of White Bear’s never-ending rolls and rambunctious terrain, two fifteen foot hills are encountered between the high tee and high green. They turn the tenth into the sort of hole that the author relishes, a hole where there is no one correct way to play it. Good players sometimes hold to the belief that if you hit to X, then you should be guaranteed a Y outcome. Such “sticks” find frustration and consternation on this hole (and perhaps the entire course). While a player seeks a level stance to aid him in placing his short iron underneath the hole, he may or may not find it upon arriving at his tee ball. The only thing for certain is that these fairways come with no guarantees. Like most greens situated on a hillock, the putting surface slopes insensitively from back to front dropping over three feet. Yard for yard, the tenth packs a punch, that in many ways, epitomizes the course.

As seen from the high point between the 9th and 10th holes, the 10th gets the second nine off to a rousing start.

A look from behind the green reveals the convoluted land that defines the fairway. An approach ten paces short of this flag rolls off the false front while one ten paces long renders a nervy downhill chip.

Eleventh hole, 180 yards; There are three ways a putting surface challenges: size/configuration, tilt/pitch and interior undulations. There are countless permutations within each category. This rectangular green surrounded by bunkers features elements of all three. The right third is elevated and features a puffed up knob. The hole location is invariably there on ‘The Angry Bear,’ which is the equivalent of Tough Day and as much as any hole location on the course, can prompt players to turn incandescent. The rest of the green is canted and slides from high right to lower back left. It and the seventh are among the most complicated greens on the course and its multi-faceted nature emphasizes the point that discerning the best play isn’t nearly as evident at White Bear Yacht Club as it is at most courses where greens are angled toward the player with monotonous regularity.

The high back right to low left cant of the green gives players fits and the objective off the tee is to place your ball left of the hole in an effort have an uphill putt for your second shot. Even an uphill chip for your second shot can be preferable to a downhill putt.

Twelfth hole, 385 yards; This is White Bear Yacht Club’s most acclaimed hole. Doak devoted an entire page to it in Volume 3 of The Confidential Guide, noting ‘…the trick is to play the tee shot out wide to the left or right (near a line of bunkers) , and then play the second shot across the approach into a shoulder of green on the opposite side, which will funnel the ball back down to the hole.’ Every course should dream of featuring an approach like this where feel/craftiness one-up a formulaic aerial shot to a set yardage. Yet, most modern architects are loathe to build greens that sweep from front to back and so the golfer is free too often to dully reach for whatever club will land his approach near the hole. Here, you might play one or two clubs less than the yardage indicates or you may aim to the sides as Doak suggests and let the bumper mounds funnel the ball close. Either way, the brain needs to be fully engrossed for the task at hand.

If the hole is on the left side of the green, then driving close to this string of bunkers becomes ideal. Though it is unknown if the Scot Watson or the Scot Ross or the English Vardon built them, there is little reason to doubt that all three Brits would recognize and approve their merit, knowing full well from Great Britain that the smaller the scale, the more awkward the stance/lie.

Any lover of links golf appreciates the beauty of only half the flag pole and flag visible. The author shutters to think how many modern architects would have bulldozed various landforms to provide better optics, which would have forever ruined the mystery and allure of a game here. The enticing manner in which the holes play up, over, and around landforms is far preferable to a course whose fairways stay contained in valleys like those at Royal Birkdale. Given the option of ten rounds between the two, the author would pick seven at White Bear Yacht Club and three at the Open venue.

This view from behind tells it all and captures how the green falls four feet from front to back. An approach that doesn’t deaden into one of the side banks will be deposited in one of three back bunkers. The copious amount of short grass surrounding the putting green adds another playing dimension.

Thirteenth hole, 515 yards; White Bear Yacht Club isn’t heavily bunkered and needn’t be; the land is the thing. Ultimately, that is its trump card. So many architects these days are adept at building handsome, rugged bunkers that modern courses are starting to look too much alike. Here the land is so singular that it never blurs with another course.

The land as opposed to bunkers dictates the narrative. As we see below, no greenside bunkers required.

Originally, the 13th green was located left in the dell. One suspects the club learned the hard way that a dell green doesn’t work well in the north through the winter months when water freezes, thaws and re-freezes.

Fourteenth hole, 335 yards; The author first played the course in the fall of 2017. The vast majority of the restoration work had been completed and on a peak autumn day the course could not have been presented better. While the front nine exceeded expectations, the superlative four hole stretch to start the second nine really impressed. Standing on this tee in a corner of the property, the author was sure that a weak patch would emerge. Instead, three of the best driving holes on the course ensued, each capped by one of the course’s finest greens.

Similar to sixteen, this hole bends to a degree that reaching for a driver is no certainty. And that’s an important attribute as any course where the player automatically reaches for a driver is lacking.

In the 1980s, the club was having a mighty problem maintaining the green and finding a sufficient number of hole locations. Pete Dye’s brother happened to be in town and went out with John Steiner and club officials to inspect it. Roy Dye’s words of praise that day helped insure that its contours were never softened.

Fifteenth hole, 425 yards; The ever rotating visuals are part of the charm. At the prior hole a downhill pitch makes everything clearly visible. Here, the golfer has done well off the tee if he can see the flag and at the next, the approach is uphill over a large bunker well short. What more do you want?! Compare that to the prosaic visuals offered at so many modern courses whereby the golfer is given a clean look at the target with everything laid out nicely. Under one scenario, the golfer has no choice but to feel a tight connection to the landscape while in the other, the same scene plays out ad nauseum.

The noble 15th green is at grade to its surrounds. It welcomes a running approach past the swale short left. Only the trees behind suggest that you aren’t playing a links and the old school mounds complete the appealing picture.

This view from behind exposes the hog back’s ridge that runs down the middle of the green. The author can attest to the lonely feeling of being back right and putting to a front left hole location. The resultant second putt from twenty feet did not go in either.

Sixteenth hole, 485 yards; The final of three consecutive, hugely appealing elbow holes, the sixteenth slides up and to the right around a fierce cluster of bunkers cut into a hillside. The author writes ‘elbow’ as that was still the more popular expression to the term ‘dogleg’ as the course was taking shape. Though the fairway moves to the right, the land slopes right to left. If the tiger tries to force the issue off the tee of this 1/2 par hole, the reverse camber fairway will insist that he play a power fade. Recall that this is the hole where Urbina removed several greenside bunkers enabling the severe green with a three foot step through its middle to shine. Sandwiched between the rigors of the fifteenth and seventeenth, the pressure is on the golfer to make something positive happen, which of course is the surest way to insure that it doesn’t.

As seen from behind, there are several ways to work a ball close to the low back left hole location. Move the hole location to a higher point and the going gets progressively trickier.

Seventeenth hole, 205 yards; While the mystery for who deserves credit may never be solved, one thing is certain: all parties involved embraced the notion that the target for one shotters need not be large. Of the five greens that measuring less than 4,000 square feet, four of them come on par 3s (the exception is the eleventh). While the tiny third hole seems wonderfully in proportion given it’s the shortest, that sense of ‘balance’ is notably absent here. Standing on the tee of the longest one shotter, the golfer can be forgiven for feeling disgruntled and that he is too far away to approach the course’s second smallest green. As such, it makes for a clever penultimate hole where the player’s long and short game are likely both tested.

White Bear Yacht Club is in good company, and joins elite courses like Cypress Point, Rock Creek, Lahinch, Morfontaine, and Swinley Forest in ending on a down note. Its Home Hole is no one’s favorite but so what? The blind drive over the iconic white bear on the hill holds one’s interest and the approach to the canted green is a nervy one should the match still be on the line. The concept of finishing with a long, difficult par 4 may be de rigueur in the United States but is alien to Scottish links like North Berwick, Prestwick and St. Andrews. White Bear Yacht Club has done well to resist pursuing unnatural acts to alter its finish.

The Home hole features a fine blind drive over a hillock with – you guessed it – a white bear acting as the mark.

Save the finishing hole, the author would love to single out other design weaknesses, as that is what a course critic is supposed to do. Yet, what could they be? The tees are simple and clean in presentation and near the prior green. The fairways deserve to be recognized as world-class, featuring movement that is human in scale (e.g. the second, seventh) to much wilder stuff (e.g. the ninth, thirteenth) and these contours act as central hazards. Starting with the sixteen foot pit at the first green, you know that bunker depth isn’t an issue so … perhaps the greens are bland? Are you kidding?! Just think about the interior contours at holes like the seventh, fourteenth and sixteenth or the swift back to front green at the tenth or the all-world front-to-back twelfth and the slinging right-to-left eleventh.Wind? Check. True, the soil isn’t sandy loam and bouncy-bounce conditions aren’t always present but the resultant slightly slower fairway speeds have the advantage of having tee balls hang up on fairway slopes creating another kind of challenge.

In short, the author can think of nothing that is missing or of anything that would add materially to the potent mix of existing features. Like Royal Hague in the Netherlands and Eastward Ho! on Cape Cad, White Bear Yacht Club has slowly and carefully pursued a plan this century to better expose their greatest asset, which are some of the game’s most delightful landforms. If you want to quibble, you could argue that a 36 hole day at one of these three courses might be too physically taxing but given that exercise is one of the game’s great benefits, that seems like a good problem to have. So, as a course with no real weaknesses and a club that isn’t interested in passing fads, there’s no surprise that White Bear Yacht Club is slotted among the top 50 on the 147 Custodians of the Game.

GolfClubAtlas once again thanks Jon Cavalier for the use of his photographs throughout this profile. Be sure to follow Jon on Instagram @ linksgems.

The End