The Honors Course

Tennessee, United States of America

The allure of escaping into the rustic comfort of the Tennessee foothills and …

… tackling one of Pete Dye’s masterpieces has proven to be one of the great gifts to amateur golf for nearly 40 years.

Good luck trying to find someone who has anything negative to say about The Honors Course. From its inception by Jack Lupton as a place to honor amateur golf to its caddie program to its contributions to the turf grass industry, The Honors promotes the finest qualities of American golf.

Situated north of Chattanooga, its 460 acres is tucked in a secluded bowl at the foot of White Oak Mountain. No outside distractions exist, no tennis courts, no swimming pool. With the practice field near the main entrance of the clubhouse, golf is clearly the thing and you enjoy it in a most idyllic setting. As you wind up the long entrance drive, your biggest worry is avoiding wild turkeys.

This naturalness is what makes the lasting impression on the golfer. Lupton deserves full credit for creating such a sanctuary, but the hands-on credit for achieving this state up until 2016 belonged to the legendary – there is no other word – Green Keeper David Stone. Dye praised Stone every chance he got and considered him one of the all-time greats. As Dye succinctly states, ‘He understands grasses and that’s what makes a golf course great.’

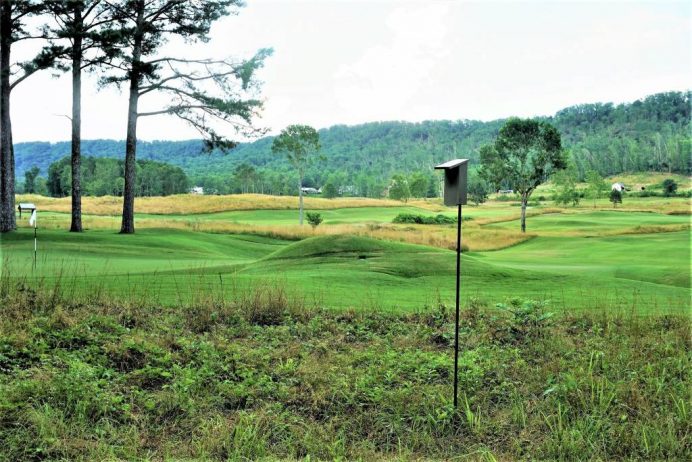

In Bury Me in a Pot Bunker, Dye details at length what Stone meant to the course. Originally from Holston Hills in nearby Knoxville, Stone was discovered by P.B. Dye as they neared completion of the course. An avid golfer himself, Stone was at The Honors Course from its inception in 1983 until he retired after the club hosted the 2016 U.S. Junior Amateur. His work with different grasses steals the show and makes the presentation of other modern courses pale in comparison. When Stone first accepted the position, he roamed the Chattanooga valley studying the different native grasses. Stone gradually then planted natives such as fescues and bronze broom-sedge to create a wall to wall environment rich in texture. As the golfer strolls the course with his caddie, he can’t help but admire the different hues of wheat, beige, rusts, tans, and browns that Stone cultivated over three decades.

In recognition of Stone’s work, the Audubon Society recognized The Honors Course in 1991 as being a wildlife habitat preservation.

Stone once noted, ‘We let nature influence our entire golf course. We have areas that we let the natural diversity of plants come in, which in turn leads to the diversity of insects, birds, and other wildlife that nature intended.’ The point is that The Honors Course very much embraces its locale; anything else would be a disservice. No surprise, wildlife is abundant. In addition to the wild turkeys, deer and fox squirrels meander. One sight to behold is the osprey that has taken up residence as it dives for fish in the lake between seven and fifteen. Various hawks join the parade as does the occasional bald eagle. Bird watching groups once toured the grounds with Stone and over 150 varieties of birds have been spotted there, including the Canada Warbler, Hairy Woodpecker, Yellow-billed Cuckoo, and Ruddy Duck. Imagine migratory birds saying, ‘Time to head to The Honors!’ The cadence of the wildlife helps establish the club’s unhurried pace.

Lupton steadfastly supported Stone and his research work until the day Lupton passed in 2010. By then, Stone had over thirty-five varieties of bent and five of Zoysia under study in a designated four acre area. Lupton and Stone enjoyed a special bond, one of the most productive in American golf. What’s staggering though is how the torch has been passed. Stone’s long time assistant, Will Misenhimer, took over when Stone retired. Today, its famous Meyer Zoysia fairways are the bounciest they have been in club history. That’s a critically important statement because The Honors Course is all about the ground. Experimentation continues. As Misenhimer notes, a new favorite grass ‘… is the Zeon Zoysia which has a much finer texture than the Meyer and has proven well suited for even the most dense shade. We use it on countless tees and around the front of the clubhouse.’

Some of the natives like the fescue and thistle that line this bunker on 10 are best appreciated from a distance!

As for the design itself, Dye told Lupton during the routing process that there were fourteen natural green sites and that he just needed to manufacture four. Two of the one shotters (e.g. the third and fourteenth) were ‘build-a-holes’ but the author is unclear which the other two were. Early on, Dye decided to eat up the only relatively flat portion of the property with two lakes. Their creation served as a source for irrigation as well as dirt and five green sites interact with them. The golfer encounters the water hazards in two distinct bursts (seven thru nine and fifteen/sixteen) and these hazards give the course a steely edge that unnerve even the best. In fact, Tiger Woods once chipped across the ninth green and into the hazard but such is his mental fortitude, he still went on to win the 1996 NCAA scoring title by four shots over Rory Sabbatini.

Nonetheless, it is the collection of the fourteen natural sites that constitute the underpinning of the course. Tick through them – the first down in a hollow, the second and fourth benched into hillsides, the fifth located on a high spot, and on and on. They are all beautifully situated and by extension, defend against sloppy shot making with an insouciance born from nature. Plenty of Dye’s subsequent commissions were on flat sites or ones where he moved a lot of dirt. The Honors Course highlights that he had an innate – even underappreciated – talent for routing a course around natural features.

With Dye’s passing earlier in 2020, it is easy to wax on nostalgically. Regardless, it doesn’t change the fact that The Honors Course embodies Dye’s trademark design elements: from short holes (nine, twelve and fourteen) to bruisers (five, fifteen), confrontational hazards (fronting water hazard at sixteen), design twists (Valley of Sin on seven, volcano bunker at thirteen), and a fabulous variety of green configurations (from shallow, round-ish ones like the fourth with its right front knob to deep, angled, canted ones like eighteen). Tie a bow around them with the course’s presentation and you have a course that is aging with a rural supple ease. Architects fortunate enough to have worked with Dye during his magical stretch from the mid-1960s to the mid-1980s include Bill Coore, Tom Doak, Rod Whitman, Bobby Weed, and Tim Liddy and they all learned invaluable lessons from him that permeate their work to this day. In short, Dye’s influence over the modern game can’t be overstated.

When you think ‘The Honors Course’, you think of Jack Lupton and the financial heft it takes to create a secluded playing environment. You think of Pete Dye and his maximizing the site’s natural features. And you think of David Stone and how smartly the course has been presented since its inception. With the passing of Lupton and Dye and the retirement of Stone, the club has entered into a new chapter. And here’s the thing: It hasn’t skipped a beat. In fact, it plays better today than it ever has. As we tour the course below, take note of how the fairways bob and weave and how the better player can gain an advantage by an expertly shaped shot to maximize his tee ball’s run. Add in the undervalued green contours and you have something special.

Importantly, the club continues to share its course freely for important amateur events on the state, regional, national and international level, including countless men and women State Amateur Championships, the NCAA Men’s Championships twice, the 1991 U.S. Amateur, the 1994 Curtis Cup, the 2005 U.S. Mid-Amateur, the 2011 U.S. Senior Women’s Amateur, and the 2016 U.S. Junior Amateur. Up next are a U.S. Senior Amateur in 2024, the U.S. Women’s Amateur in 2026 and the return of the U.S. Amateur in 2031, forty years after The Honors hosted its first one. Its Honor Circle pays tribute to the Tennessee greats like Cary Middlecoff (who won the Tennessee State Amateur Championship four years in a row) and Lew Oehmig (who won the same event a mere (!) eight times across five different decades). With its new Bermuda greens, the author looks forward to the day when the USGA awards it the Walker Cup. Suffice to state that Lupton’s vision of celebrating the best in amateur golf has been realized.

Holes to Note

First hole, 405/380 yards; Dye met Donald Ross when Dye was stationed near Pinehurst at Fort Bragg in the 1940s. Dye’s reverence of Pinehurst No. 2 is well documented and ticking through his most accomplished designs – Crooked Stick, The Golf Club, Harbour Town, Casa de Campo, TPC-Sawgrass, Long Cove, The Ocean Course at Kiawah,Whistling Straits and here – one similarity jumps out: They all start with a medium length or shorter two shotter. How much of this is attributable to Pinehurst’s famous opener we will never know but Dye clearly believed in getting the golfer into his round before presenting the player with the day’s thorniest matters.

Arguably Dye’s finest opener, with the rich texture in the foreground complimented by the beautiful long view.

The fairway tumbles left with the top of the white flag peaking out above the mound.

The first of many angled greens, though this one is different in that the back of the green is a good three feet lower than the front edge.

Second hole 560/505 yards; Opened in 1983, The Honors Course came along when the amateur and strong club player hit the ball a similar distance. Technology has changed that and The Honors Course has changed with it, going from 7,064 yards at inception to today’s beefy 7,500 yards from the back markers. One of its three shotters (the sixth) stretches to 600 yards but the other three can be reached in two. All four present elevated greens that make for difficult targets from ~250 yards. Water isn’t a threat on any of them but recovery for the desired birdie often proves elusive. While the top amateurs try to flex their muscle to gain an advantage, Dye’s placement of the greens on plateaus lends them ample defense. It’s the best of both worlds: the tiger is encouraged to attack but natural defenses await. No tricks required.

The slender, angled 2nd green is no mean feat to hit and hold with anything other than a short iron.

Third hole, 220/180 yards; This is vintage Dye at his minimalist best. Nothing was disturbed tee to green but rather Dye focused on the rolling putting surface with its front middle bowl and back tongue. The hole rests peacefully on the land and the first timer is shocked to discover the presence of a deep back left bunker. Nothing from the tee alerts the golfer of its existence nor its nightmarish recovery propositions.

The putting surface is the high part of its surrounds and therefore possesses a similar ‘hit it or else’ dilemma to the famous ones at Pinehurst No. 2. It is an important green to hit in regulation.

Under no circumstance should the golfer go long left into this hidden bunker. A ‘7’ on this hole likely cost the form player the 2014 Southern Amateur.

Fourth hole, 465/425 yards; The land is the predominant feature at The Honors Course, more so than man-made features like bunkers or lakes. Take this long hole for instance. Only one 60 yard long strip bunker at grade with the land was required and the hole pivots around it to the right. The green itself is bunkerless and looks straight from Scotland. If not for the trees, you would swear the ocean was just over the hill.

The golfer is always given something to accomplish off the tee. Here a power fade is ideal with the next hole asking, of course, for a draw.

What a fetching approach shot! Too bad more such bunkerless green complexes aren’t found in America.

Fifth hole, 490/410 yards; Too many doglegs don’t offer an advantage off the tee but not here. A high draw that hugs the inside left both shortens the approach and improves the angle into the green, which is guarded by a five foot deep bunker on its right. It represents a favorite design ploy of Dye’s, calling for one shape shot off the tee and the other into the green. Because he was a part of the American golf landscape seemingly forever, people tend to forget that Dye was a splendid amateur from the 1940s through at least the 1970s. He grew up shaping the ball and viewed the ability to do so as a great barometer of a man’s skill. Here, a draw off the tee is often followed by the need to hit a high floater to the back right half of the angled green. The player who does so sends a clear message that does not go unnoticed by his opponent.

The golfer readily discerns what shape shot is required from the tee. The question becomes, can he execute it?

Only the left portion of the green is visible above. Today’s hole location is front edge but a back right hole location requires 2, potentially 3, more clubs.

Sixth hole, 600/520 yards; What is absent at The Honors Course? A straight hole! All the three shotters twist and turn across some of the course’s best property. For that matter, so do the two shotters, which is why a good driver of the golf ball delights in an invitation here. The challenge of The Honors Course is evenly spread across all facets of the game. The need to be long and shape the ball either direction is evident on most tees. Accurate approach shots are thoroughly explored too. Finally, with only a few exceptions, the greens are not heavily bunkered, though the modern player may wish they were. Take the sixth as an example. Ostensibly, this should be a birdie hole. A power fade off the tee and another onto the elevated green and all is well. Yet, to stray on the first or second invites an entirely different sequence of events. Perhaps Dye absorbed this classic Golden Age ‘give and take’ between the architect and player from Donald Ross and Pinehurst No.2? Having lived by Pinehurst for twenty years, the author states categorically that the balance of the ‘get-able’ three shot holes against the demanding set of one shot holes is eerily similar to that of Pinehurst No. 2. The pressure to make birdies on the three shotters at both courses is acute – and the result often unflattering.

The golfer feels confident reaching for a little extra with a power fade off the tee. However, the challenge …

… tightens as one approaches the green.

Recall how the third green was bathed in sunlight moments ago? A storm has quickly closed, highlighting that shifting weather patterns play a frequent role in a round here in the Tennessee foothills.

Seventh hole, 460/410 yards; Cypress Point’s routing famously takes a golfer in and out of different environments. Same applies at The Honors Course as the golfer is transported in stages into three distinct environments of trees, lakes and prairie. Specifically, the first six holes enjoy the advantages that come from holes cocooned in treed surrounds at the base of White Oak Mountain. Then, a two part transition occurs whereby the golfer is first brought out into the open as he loops counterclockwise around two lakes (the bigger one being 560 yards across) before heading into the southern end of the property that is distinctly prairie in feel. After fourteen, the golfer traverses past the two lakes again before returning into the treed environs for the final two. While Mackenzie made the transition seem seamless, Dye used the opportunity of different environments to rattle the player, in particular between six and seven and fourteen and fifteen. Here, after circumventing the overhanging branches at six, the golfer walks uphill to the seventh tee and is starkly introduced to the lake. No comfort or aiming point is provided and strong is the first time player who isn’t perturbed. Same for the transition between the treed fourteenth and the fifteenth along the other side of this lake. Dye liked to remark words to the effect, Once you get the good player thinking, you have him. Without doubt, Dye viewed it as an architect’s responsibility to unsettle the player from the comfort of a routine – and seven does so like few others.

Don’t let the distant white flag on the left act as a siren. Though the fairways is 55 yards wide, the author doubts that a single golfer in the club’s 37 year history has ever stood on the tee and remarked, “What a generous fairway!”

Normally, the prevailing wind would have the flag blowing right to left. Today’s pop-up storm had other intentions. At 6,800 square feet, it’s the biggest green but like the fairway, the target hardly feels ‘ample.’

Eighth hole, 200/165 yards; Two holes (here and twelve) play directly at the mountain and those shots are some of the most handsome to watch as the ball climbs and drops against the distant hillside. Playing beside an ocean has undeniable appeal but when the Honor’s autumnal colors of green, red, orange and gold are in full roar, few environments are more special.

The tiger tends to draw the ball while the rest of us hit a fade. So what does Dye do? He puts the most calamitous hazard along the left of holes 7, 8, 9, and 15 which frees up us bogey golfers to enjoy ourselves.

Ninth hole, 365/350 yards; Judy Rankin commented during the 1994 Curtis Cup how these Zoysia fairways produce lies that are ‘boringly perfect’. The ball does indeed sit up, begging to be hit with flush contact but equally important, the Zoysia fairways promote the release of the ball while at the same time, provide just enough friction to allow balls to come to rest at all sorts of positions in the fairway. To understand why that is important, let’s examine this hole. The fairway plays through its own shallow valley and the dominant fairway slope is from right to left. Rare is the tee ball that draws a level lie. Yet, with water short and along the left, the right handed golfer is none too thrilled to find his ball often times slightly above his feet for his approach shot. A pull or draw is disaster so golfers do all sorts of odd things to prevent that from happening. Consequently, many a recovery shot is played from right of the green. One of the most famous incidents occurred with Justin Leonard during the 1991 U.S. Amateur. He missed the green right by four yards. Upon seeing his opponent in a similar situation chip across the green and into the water, Leonard wedged his ball 90 yards back into the fairway, wedged onto the green, two putted and won the hole! Think about what that took for Leonard to do that – no wonder with resolve like that he was able to win The Open Championship in 1997 at Royal Troon. Since that event, the green has been raised along the left but … green speeds have also increased, so play smart. Very neat that many of the club’s most famous moments have played out on a sub-400 yard hole.

The tilted 9th fairway is a continual source of consternation.

Though its fairway is generous in width, the 9th remains uncommonly difficult for its length, thanks to the orientation of its long, narrow, two tiered putting surface against a finger of the lake.

Eleventh hole, 590/540 yards; As we saw at the second, a favorite design feature of Dye’s is to place an angled green at the end of a three shot hole, thereby rewarding the golfer who advances the ball long down the fairway in two. He liked the ploy so much that he used it multiple times at both The Ocean Course at Kiawah and French Lick. Dye also used it at the seventh at The Medalist but the Tennessee landscape here with a deep depression left off the tee and its winding fairway accentuate the charms of this version. Like the fourth, it is another long hole with but one bunker. After two good cracks here, the golfer has a clear look down the spine of the green while his opponent, if he strays at all, will be forced to flirt with a deep greenside bunker. Of course, the tiger might well go for the green in two but holding the angled, plateau green from far back comes with its own challenges.

An approach from long right comes down the length of the green. Meanwhile, an approach from farther back in the fairway is more problematic, given the depth of the greenside bunker.

Twelfth hole, 380/340 yards; There were several outcomes from Dye’s 1963 trip to Scotland and subsequent return pilgrimages. First, he became enamored with what different grasses could mean to a course in terms of texture and contrast. Second, short two shotters captured his fancy. Third, he found merit in having hazards come in all shapes and sizes. Fourth, he discovered the occasional blind shot was not only fine but important. All four of these beliefs are captured within this highly regarded, beloved hole. It plays toward the far hillside to a green perfectly situated on a hummock. Seven sunken bunkers ring the front of the green, turning this very much into a placement hole like the ninth. A mere 23 yards deep, the green is the course’s smallest. The cleverly sloped left to right putting surface places a premium on keeping the approach beneath the hole – and the high back left hole location is to be treated with kid gloves. The twelfth is now in the heart of the course’s prairie portion, a statement made true by a tornado that swept through on Easter Sunday, 2020. No one was hurt but this portion of the property was handsomely opened up by the felled trees. The club’s new architect of record, Gil Hanse,was presented by this freak weather event some interesting opportunities to further amplify the course’s three distinct playing environments. No doubt he will take advantage.

The view from the 12th tee sums up the rural charms of The Honors Course.

A tee ball blocked right leaves the golfer with unwanted depth perception issues to resolve in approaching the course’s smallest target of 4,000 square feet.

The front right bunker with its vertical face of stacked sod must be avoided and the green contouring allows the golfer to do just that. The dastardly back left hole location on top of a small plateau is seen above.

Thirteenth hole, 410/380 yards; Designs sometimes become prisoners of the overall experience. The Honor’s discrete entrance, the long drive in, the unhurried ambiance, the peace and so on define the playing experience, which sometimes means specific design components get the short shrift. Take the greens contours here. Starting straightaway at the first which cascades from front to back, the third green with its punchbowl right, the fourth with its front right knob, the long angled fifth green, the two tiers at the ninth, and here, the green contours taken as a set surely rival Dye’s finest collection. Yet, the author has never once heard them discussed at length. At the thirteenth, the green is angled from front left to back right and places a premium on a draw to the inside of the dogleg left. Deeper than wide, the putting surface flairs up at the rear. One of the most delightful shots is to use the back washboard to send a ball back toward a back right hole location. That shot, that moment, that green isn’t what you will first recall about The Honor Course but it and the other putting surfaces go a long way toward explaining the design’s enduring appeal.

This low hollow gobbles up any weak approach. Meanwhile, note how the putting surface swoops up at the rear. Most club golfers habitually under club but Dye gives the player reasons to be bold at 13.

Fourteenth hole, 175/135 yards; The hole that epitomizes what grasses mean to the course is ironically its shortest one. Initially, a bunker stretched from tee to green but over the years, grasses and vegetation were wisely allowed to take center stage, lending the hole its incomparable rough hewn quality. Though this is one of Dye’s aforementioned four manufactured holes, it doesn’t feel like it. Indeed, that’s what great architecture is about: find a site’s best natural components and incorporate them into the design but when none exist, lend nature a helping hand. Dye and Stone working in concert did so flawlessly here. Finding such a challenging short one shotter that features no water is an infrequent delight. Recovery shots abound here, though you may not exactly like yours (!) as a game of ping pong can break out across the narrow green, which is a scant 9 yards across at the front. Standing on the tee with a short iron, the golfer might feel in control but how quickly that can change! Dye built numerous great fourteenth holes including those at Crooked Stick, The Golf Club, Harbour Town, Long Cove, TPC Sawgrass and Kiawah but this is the author’s favorite.

The rugged, natural appearance of the teasing 14th, a short iron hole full of mystery.

A sinewy bunker snakes through the grasses but is largely unseen on the tee.

The front hole location is particularly ticklish because of the horseshoe bunker. The back locations are made tough by the green contouring and back drop-off.

Fifteenth hole, 475/420 yards; Both the designs of the Stadium Course at TPC Sawgrass and The Honors Course offer formidable moments. No surprise, the former was built specifically to test the best professionals and the later to test the best amateurs. Yet, there are some holes at TPC that the author would not like to face on a regular basis, especially its famous, water drenched final pair. Compare those two holes with the island green fourteenth and fifteenth holes at The Honors Course. All four holes are demanding but the opportunity better exists for the thinking golfer to coax his way around the two holes at The Honors Course. Certainly, the golfer is highly unlikely to ever lose a ball at fourteen and fifteen enjoys greater playablity than eighteen at TPC. Here, the club golfer can play short right and have a reasonable chance of a chip and putt par yet the hole remains hugely satisfying to the tiger who must shape two perfect shots. Both fifteen at The Honors and the Home hole at TPC are the highest handicap holes on their respective sides and are indisputably tough. However, the more low profile features of fifteen, its bailout area short right and a degree or two less of pitch from right to left in the green means the fifteenth enjoys just that bit more wiggle room to where the hole becomes palatable on a regular basis for a 7 handicap. The difference may seem niggling but the author thinks it’s huge. For a course to be considered ‘great’, one must delight in playing it on a regular basis. The Honors Course passes that test with flying colors.

Dye frequently utilized crescent fairways and here is a prime example. Draw a line from the tee to the distant white flag and note how the fairway stays well right of the direct line.

Intimidating for sure but with the caveats of a bailout area short right and a green that accommodates a bouncing approach.

Sixteenth hole, 200/155 yards; Imagine playing this course when it opened in 1983. Seeing limestone edged lakes right beside several fairways and greens would have been both startling and terrifying all at once. Almost forty years later, such use of water hazards flush against the playing surfaces has become more commonplace. Yet, take a look at the photograph of sixteen below. Is it the water that grabs your eye or the carefully cultivated palate of colors everywhere else? This one shotter dutifully transitions the golfer from the openness of the past nine holes and reintroduces the player into a treed environment for the final two. Its risk reward qualities highlight that The Honors Course is especially well tailored for match play.

Tranquil but deadly, the 16th features one of only three forced carries on the course. Limestone proliferates in eastern and central Tennessee so what a prudent choice to deploy it instead of bulkheads.

Seventeenth hole, 545/470 yards; Everything revolves around two facts: it’s the course’s shortest three shotter and it features the deepest greenside bunker. A bullet draw is ideal, hitting the firm fairway and then scampering downhill toward the green. The second needs to be high but can the the golfer gain the required height from the down slope to carry Bertha and hold the 32 yard deep green? Ultimately, that’s the thing about The Honors Course. Its design does just what it was intended to: identify the better player. A lot of modern courses have been built since that feature bigger, gnarlier bunkers yet such features often have little bearing on the golf. They photograph well but they don’t deter the golfer from doing anything other than bombs away. The features at The Honors Course do more with less, which is what one would hope to find in rural setting.

A treed corridor beckons the golfer onward.

Dye considered the second half of 17 to be ‘cathedral looking.’

Bertha is 13 feet deep and the first bunker shot often leads to the next shot being played from the grass face. The green is steeply pitched and the tension between wanting an uphill putt and not getting into Bertha is fabulous.

Eighteenth hole, 470/420 yards; Dye designed the Stadium Course at TPC Sawgrass and Long Cove immediately before The Honors Course. Lupton repeated on numerous occasions that he wanted a straightforward course or as Dye describes it, ‘a formidable golf course but one that held the line when it came to trickery.’ There would be no manufactured blind shots a la the fifth at Long Cove here. This gentle dogleg to the right characterizes the natural, honest nature of The Honors Course as it gracefully flows across the rolling terrain. A valley separates the tee from the fairway and another one separates the middle part of the fairway from the green itself. A gorgeously routed hole with Dye showcasing the site’s natural features.

The tee ball plays over one valley and …

…the approach another. The angled green is one of the deepest on the course at 37 yards and provides numerous challenging hole locations based on the green’s left to right tilt.

Lupton’s vision of having the best amateur players such as Phil Mickelson, David Duval, Justin Leonard, Tiger Woods, and Gary Nicklaus come to Tennessee has been realized. Yet, the round that the author will forever associate with the course came from its long time Head Professional, Henrik Simonsen. The Dane’s bogey free 66 was a road map to how to tackle the course. No surprise, half the birdies came at the par five holes though deft recovery shots were required in two cases. The ability to shape the ball in both directions was paramount. Controlling a shot’s trajectory – from flattening it out on tee shots to enjoy added run on fairways like the first and fifteenth to hitting soaring approach shots in two into the par five eleventh and seventeenth holes – proved essential. Driver is not always required; being in position is. When in trouble, get out. Finally, finding the right portion of the greens switches the mindset from defense to offense. The design asked the 53 year old man the full range of questions, from possessing power to staying in position to displaying touch. To witness first hand a cunning veteran demonstrate the full repertoire of required shots was extraordinary. Why people crow about Bob Jones’s ‘perfect’ 66 at Sunningdale Old was made clear that June day in Tennessee.

Integral to the success of the club is how it is run. The Honors is a throwback to National Golf Links of America, Pine Valley and Oakmont where autocrats once saw to it that things were done once and done right. Lupton was friends with Bob Jones and Jones’s views on amateur golf shaped Lupton’s thoughts. Similar to the aforementioned clubs, The Honors exudes a confidence that only comes from a series of relentlessly right decisions over an extended period of time. At The Honors, change for change sake simply has never occurred.

Dye’s six decade career was littered with glamorous opportunities, from the rocky coastline of the Dominican Republic to the sand dunes on Kiawah Island. As he became sought after, commissions came his way that featured a housing component. In fact, residential courses are what drove the boom in construction during his lifetime. Alas, with houses comes compromise and that is a word with which Lupton was unfamiliar. Looking back on Dye’s career, The Honors Course (contiguous block of land, no housing, rolling topography, one man to whom to answer) was one of the handful of best opportunities he ever received. Without the threat of a professional event and the cameras that come with one, Dye adhered closer to nature than many of his subsequent designs, which helps explain why The Honors Course stands the test of time as well as any design he ever built.

The End