Koninklijke Haagsche

The Hague, Netherlands

A dream landscape for golf with man pitted against nature on a grand stage.

A famous chef once remarked that ‘Mother Nature is the true artist.’ The better the ingredients, the better the meal. Yet it is how the chef mixes the fresh produce, how he develops and accentuates flavors that creates a culinary experience. Similarly with golf course architecture, the better the landscape, the better course in the hands of a master architect. Inspired pairings of landscape/architect abound from the Golden Age of golf course architecture (Herbert Fowler and Eastward Ho! on Cape Cod, Seth Raynor and Fishers Island, Alister MacKenzie and Cypress Point, William Flynn and Shinnecock Hills, the list goes on and on) with one of the greatest pairings drawing to a close the Golden Age.

In 1937, Daniel Wolf hired the English firm of Colt, Alison & Morrison to build an eighteen hole course on the other side of a ridge from his estate house twenty-five kilometers southwest of the country’s capital of Amersterdam. Their drive up to Mr. Wolf’s house couldn’t have been too inspired as the surrounding land is flat in typical Dutch fashion (yes, 20% of the country is below sea level!). Regardless of the prior correspondence between Wolf and the firm, nothing could have prepared Hugh Alison and John Morrison (at this late stage in his career, Harry Colt’s traveling days were numbered and he never saw Haagsche) for the sight that unfolded once they climbed the path and reached the top of the ridge.

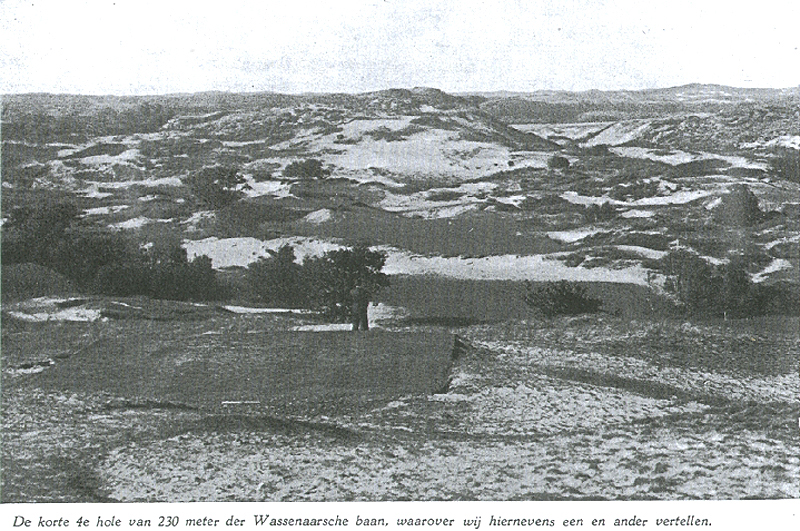

Stretching out in all directions from this ridge line were rolling sand dunes as far as the eye could see. The benefits were immediately evident of being on the west side of a coastline where the prevailing westerly winds and currents had been depositing sediment and forcing it inland for centuries upon centuries. Large enough to create an heroic setting without being too big to hinder good golf, the dunes were perfect terrain, literally every architect’s dream. Paul Turner, a Colt historian, sums it up nicely when he writes, ‘Though I haven’t seen Kawana yet, I think it is safe to say that Haagsche is the boldest site with which the company ever worked. St George’s Hill, Pine Valley, and Hamilton run it close but the fairways on those courses don’t heave to and fro like those at Haagsche. The course is spectacular and needs sturdy legs but the dunes are the right size and the holes never slip over into being too severe and fluky.’

Effort to divide the design credits between Alison and Morrison is a fool’s game. For example, documents exist that credit each individual for the routing. Having worked with Colt for so many years, both had the ability to string one hole after another and have them cumulatively capture the best attributes from a particular property. That’s certainly true here and Alison and Morrison waste no time in giving the golfer the full flavor and joy of the rambunctous topography. The first hole is a three shotter that desecends from one of the property’s high points to a very low one and then the golfer is marched straight back up the hill to the second green. The third plays across one valley and then over a large depression before the one shot fourth plunges forty-five feet from tee to green. The three shot fifth gradually climbs uphill with the walk from its green to the sixth tee being steeply uphill. However, from this pulpit tee, the golfer is afforded a magnificent long view over most of the front nine. This kind of roller coaster ride never abates from start to finish and first time visitors are often left in breathless wonderment as to what they have just experienced.

Having completed the routing, Alison and Morrison let the ground provide much of the golfing challenge and not many man made hazards (a.k.a. bunkers) were required. For instance, on the 480 yard tenth there isn’t a bunker from tee to green. Yet, to reach this short three shotter in two, the best line is down the left (i.e. the side with the most severe trouble). As one shys away to the right, the natural slope and landforms kick the tee ball yet farther right. From the left, more level stances are afforded and the golfer enjoys a preferred angle into the green which is bunkered front right. It is a classic risk/reward hole with the better player given something to do in order to gain an advantage yet it is a hole that doesn’t loudly proclaim attention received from the hand of man. Like Colt, both Alison and Morrison accomplished their work in such a manner that they often don’t always get the credit that they deserve. They never built silly water features or did anything that called attention to themselves as they were content to let the holes and property speak for themselves. In the case of Royal Hague, only twenty-three greenside bunkers and one fairway bunker were required.

Look closely at the photograph below of the eleventh green complex. Yes, it would be easy (as well as false!) to say that Alison and Morrison just draped the green over the ridge, threw green seed down and voilà , a putting surface was born. Their mastery of sighting the depression, incorporating the natural ridge line into the green itself, smoothing off the landform to create a putting surface and then blending the surrounds easily escapes the undiscerning eye. While in stark contrast to some modern design houses, that’s just the way they liked it, too.

The benefits of working with sandy soil and of avoiding the use of heavy machinery are fully appreciated by admiring the graceful landforms above. Representing golf course architecture at its finest, the simplicity of the eleventh green complex is deceiving as it is rife with golfing qualities. Getting it right took time and finesse.

Holes to Note

First hole, 505 yards; Pace of play experts frown upon reachable par fives as opening holes. Yet, the view from the tee of the long fairway tumbling away beneath as it heads into prime dunes country is so enticing who would argue with Alison’s and Morrison’s decision. Indeed, credit belongs to Daniel Wolf that such a hole was even possible as most owners insist upon a clubhouse occupying the property’s high point. Wolf had a different (i.e. better!) idea and he was insistent that the clubhouse not be visible from the course. Thus, approximately ten acres of prime land remained at the disposal of Alison and Morrison with the first tee, ninth green and tenth tee all owing their creation in part to the wisdom of Mr. Wolf. A gentle opener just as Colt preferred, the golfer needs to be ready to play nonetheless as the first and fifth are the two easiest holes on the course and he dearly needs to take advantage of these reachable three shotters if possible.

Few first tees afford a more exciting prospect than at Haagsche.

A rarity at Haagsche, the first green sits below from where the golfer plays his approach shot and a running shot can readily find the green. Many of the other green complexes are less kind as they are elevated, thus shrugging balls away.

Second hole, 390 yards; The heart of Haagsche lies in the strength of its two shot holes. Cumulatively, they rank among the finest two dozen sets or so found in world golf as they are blessed with a staggering amount of variety. Some of the game’s great long two shotters (e.g. the sixth, fourteenth, fifteenth) are matched by some of the best short holes (e.g. the third and seventh). The second is one a slew of holes that measures around the 400 yard mark and whose uphill approach shot makes it play longer than the card suggests. Frank Pont is the current architect on record at Royal Hague and his January, 2008 Feature Interview on GolfClubAtlas.com is a must read. In it, he details the state of the course when he was initially hired in 2004 and what he has done to bring back as much of Colt, Alison and Morrison’s work as possible. Here at the second is a prime example where a smallish green built by Frank Pennick in the 1970s was out of character with the other original Alison and Morrison greens. Pont created a skyline green twice the size and had it fall away to the rear so that once again, the second feels like it belongs on a Golden Age course. Indeed, the crowned greens at Royal Hague are one of the course’s distinguishing marks and the camber helps identify who has put a good strike on the ball – as well as who hasn’t!

What goes down must come up. As seen from the second tee, Alison and Morrison’s routing attacks the land in all sorts of manners.

As seen from behind, the second green now drifts to the rear. A ball that comes in too hot will likely find one of the hollows or depressions behind. Short grass wasn’t as frequently used in the Golden Age around greens but improvments in agronmony make it a very effective hazard, requiring a deft touch for recovery. The all world third hole stretches away in the distance.

Third hole, 385 yards; The fact that Haagsche occupies wild, tumbling land is well known but how does that translate into good golf? On land with continual movement, many architects would get tripped up connecting one hole after another. Not Alison and Morrison. Each and every hole exploits the land in an appealing – and varied – manner, yielding holes of distinction. One of the most memorable is the third, where a drive over a steep valley is required. If well positioned in the right corner of the fairway, the golfer enjoys a fine look at the green. More times than one might hope though, the tee ball gets pulled into a giant depression along the left side of the fairway, leaving a blind approach. Alison and Morrison welcomed the occasional blind shot as without them, the course would do a poor job of properly reflecting the naturally heaving terrain.

How can a course over modest property compete against the thrills provided at Haagsche? Answer: It can’t. Seen above is the tee shot for the third with its do or die carry to reach the fairway.

Just making the carry to the fairway isn’t enough as the golfer still needs to position his ball correctly. A huge bowl along the left swallows up tee balls and leaves the blind approach as seen above.

Tee balls that hug the inside right of this dogleg (i.e. closer to the side of the trouble) stay on the higher ground and afford this view for one’s approach.

Fourth hole, 220 yards; High spots in general afford the most expansive, long views. As Haagsche is an open links with stunted vegetation, that certainly holds true. Even better, the course borders protected dunes land on three sides so the views are often breathtaking. On non-windy sites, golfers take in the long views and then enjoy the advantage that elevation brings. However, on windy sites of which Haagsche is definitely one, elevation brings its own special challenges. Standing on high, the golfer has no way to protect his tee ball from the wind and that becomes a primary change from Haagsche’s numerous elevated tees (namely, those at the first, fourth, sixth, eighth, tenth, eleventh, thirteenth, fifteenth and eighteenth holes). Here at the fourth, how well he flights his ball goes a long way in determining the success in keeping the ball on the desired line to the green located some forty-five feet below. The GolfClubAtlas.com Facebook page has a video showing Byron Nelson hitting the perfect low, boring knockdown into this green – if only we were all so talented (!) as the Texan who grew up playing in the wind.

This exhilarating view from the elevated fourth tee will never be marred as the land in the distance is protected coastal property.

The fourth is aerial golf all the way as a fronting bunker has sealed off the entrance to the green since opening day in 1939.

This view from behind the fourth green captures the hole’s downhill nature.

This 1940s photograph is the landscape upon which Alison and Morrison feasted their eyes. A concerted effort is now under way to restore these sandy qualities to the course.

Sixth hole, 470 yards; Despite the obvious merits of the land and routing, if each hole ended in a dullish green complex, it would all be for naught. As greens are the ultimate target in golf, their quality makes – or breaks – a course’s lasting appeal. As previously mentioned, Haagsche’s greens elevate the course into the top tier of courses in Europe and there is no greater example of why that is so than here. Only half of its 6,300 square foot putting surface is available for hole locations, so severe is the turtleback nature of the putting surface. Indifferently struck approach shots bleeding away left or right are shunted away from the green from where the golfer then faces a ticklish recovery up one of the green’s slopes. In part for these reasons, Kyle Phillips has cited this half par hole as one of his favorites in world golf.

Challenges abound at the sixth with this sandy wilderness some two hundreds from the green needing to be avoided off the tee. Farther ahead, note how the green was built up to be the high point of its surrounds.

The green at the sixth is an unbelievably difficult target to hold as it falls off sharply to its left as well as to its right, as seen above from behind the green.

Koninklijke Haagsche

The Hague, Netherlands

Seventh hole, 380 yards; Golf architecture at its highest level is about the diversity of challenges posed of the golfer. To appreciate Haagsche in this regard, just look at the green complexes in the four hole stretch from the sixth through the ninth. First there is the domed, exposed sixth green that sheds balls every which way, frustrating the good player who is likely trying to hit it with something like a long iron or hybrid. In contrast at the seventh, the golfer encounters a sunken green placed behind an eighteen foot tall dune that obscures a good portion of the putting surface. Assuming that the wind isn’t against, the golfer may only have a short iron in his hand but he certainly needs to hit the fairway, ideally the left side if he wants to have a view of the course’s smallest green at 4,400 square feet. Next is the eighth, a long one shotter down off a dune where everything is in clear sight and where the green nicely accepts shots that hit short and chase on. Lastly is the uphill ninth, where the challenge comes in flighting the ball from a sloping stance in the fairway to a green with a dramatic false front perched on top a dune. Not only do all the holes look great as they flow across the tumbling terrain, they possess great golfing qualities with variety that only comes from such a landscape.

A tall dune short right of the green and sharp drop offs right and long make the seventh one of the tightest defended greens at Haagsche.

Twelve hole, 170 yards; A par three of such excellence that even the master par three builder Harry Colt would thrill to call it one of his own. Played from high point to high point across a shallow valley, the green epitomizes the requirement posed at Haagsche for crisp, accurate iron play. Past the lone front right deep bunker, there is a eight foot deep swale where Gordon Brand Jr.’s ball came to rest in the final round of the 2010 Van Lanschot Senior Open. Lying on short, tight grass, Brand had every recovery option available to him, from a three wood all the way up to a wedge. His hooded mid iron was well executed as the ball bounced into the upslope but the green’s right to left tilt took the ball well past the day’s right center hole location. The resulting bogey helped pave the way for a win by his good friend George Ryall.

At 6,400 square feet, the twelfth green is the largest on the course, an unusual distinction for a medium length one shot hole. As is evident in the photograph above, the green is the high point of its surrounds and its pronounced back right to front left tilt makes recovery from any shot missed right particularly problematic. Less evident is the deep swale masked behind the front right bunker.

Thirteenth hole, 425 yards; Haagsche briefly opened for play in 1939 just prior to the commencement of World War II. Given that steel had replaced hickory as the preferred shaft much earlier that decade, Haagsche was always designed with steel in mind, something not true for a majority of Colt, Alison & Morrison courses. Hence, Haagsche has always enjoyed a certain robustness to it. New tees at such holes as the seventh and eighteenth have helped insure that its taxing nature hasn’t been dissipated by the recent advances in technology. Here is the only example where a green site has been moved to help allow a hole to retain its intended challenge. In 2007, Pont pushed the green back and right, thus adding another twenty yards. The green rests comfortably to the left of a dune and few, if any, would guess that it isn’t an original. This hole marks the start of three burly two shot holes in a row, a stretch that the members consider the Dutch version of Amen Corner.

As seen from behind, Pont moved the green back twenty yards and placed it at the base of a dune.

Fourteenth hole, 425 yards; Tucked in a chute, the golfer looks out from the tee and sees … nothing. Or at least, he sees nothing that provides much comfort. Out of bounds is clearly marked hard down the left and scant view of the fairway is afforded from the tee. Yet, reality is different as this plays as one of the widest fairways on the course. In fact, for a forty yard stretch, it is a shared fairway with the fifteenth and the landforms down the right offer a fine way for the golfer to play away from the out of bounds and still have his ball kick left and into the right center of the fairway, a prime spot to approach the uphill green. Placed in a saddle atop a dune, the green is the single hardest target to hit and hold at Haagsche. Anything short readily rolls back down the hill twenty yards while anything long is fed away by short grass to a depression nine feet below the putting surface. Holding this green in regulation is a sure sign of a golfer in fine form. Even the senior professionals at the Van Lanschot found it a beast with the fourteenth playing the most over par of any hole for the three rounds.

The white knuckle moment of the round occurs on the fourteenth tee whereby the golfer is afforded little assurity that anything good can possibly happen with his tee ball! Note the attractive green location up in the saddle ahead.

This photograph was taken three months later and from a forward position than the one above. Note the extensive clearing, especially on the dune to the right of the green. As compared to the other photograph that looks like a hillside shrouded in brush, the golfer once again is keenly aware that he is playing golf through rousing sand dunes.

As seen from near the fifteenth tee, the fairway contours and superb green placement are all that were required to lend the hole its timeless challenge.

Alison and Morrison ask the golfer to fit his approach shot onto a green between two dunes. Generally played from a hanging lie, a clean strike is not always achieved and the sight of the two balls finishing at the right front of the green’s false front is a common one.

Give the club credit for continuing to remove brush and for opening up such green sites as the seventh and fifteenth.

Sixteenth hole, 385 yards; In an appealing way, Haagsche is anachronistic in that it doesn’t readily lend itself to today’s power hitting. Woe is the golfer bent on length and who insists on playing high trajectory shots in such a windy environment. Haagsche’s humpy-bumpy fairways and dunes covered in thick, low lying vegetation require precision and cunning ahead of brute strength. A hole like the sixteenth shows the risk reward tension frequently found throughout this design. Long down the right affords the more level lies into the green but that’s the side where the penalty is greatest should one miss it. Shy too far left though and the golfer may end up tangled in a gnarly lie or with a hanging lie with the ball well below his feet for his approach shot. And of course, the hole even plays differently from season to season. In a dry hot summer, just finding the tilted fairway becomes a real challenge with golfers gearing back to nothing more than a hybrid off the tee. Like with so many of the holes here, the golfer must continually recalculate both distance and line to best play the hole for the prevailing conditions.

Though the fairway swings right, a draw is often times the preferred shape tee ball in order to hold the fairway when it is baked out in the summer months.

Seventeenth hole, 170 yards; Colt, Alison & Morrison built as many par threes of merit as any firm that ever worked in Europe. The first three at Haagsche (the fourth, eighth, and twelfth) are all of high quality. However, the old seventeenth was a shortish par three to a small green that lacked their usual flair. Something must have happened to the original hole and change was called for. Try as Pont might, there was no historical information to guide reconstruction back to its original design qualities. Left to his own interpretation, Pont pushed the championship tee ten yards back and built a modified Redan that perfectly fits atop the ridge line. The high right hole locations are scary as a steep bank falls away twelve paces to the right of the green. All golfers delight in trying to access the back left hole locations by playing a draw and letting their tee balls feed right to left along the slope.

The newly exposed sand in front of here and the next tee are more examples of the club’s on-going efforts to reinforce that the golfer is playing across sand dunes. For today’s hole location, a draw at the middle bunker is the ideal shot as it will release and chase toward this back hole location.

Eighteenth hole, 550 yards; Some critics nominate this as the best closing hole in continental Europe, which surprises the author as the hole is quite different from the other holes at Haagsche. First, the golfer actually sees the clubhouse as it acts as a backdrop for the entire hole. Second, with trees left and right, it is both more enclosed and indeed sheltered than the prior seventeen holes. Depending on the state of one’s game, the fairway can even appear narrow. Third, this is the flattest fairway on the course and the golfer may finally enjoy a level stance on back to back fairway shots. Still, there is no doubt that the Home hole’s length creates a demanding finisher as it forces the golfer to keep executing to the end without the luxury of merely steering the ball down the fairway. Just as Byron Nelson – he sliced his tee shot out of bounds here and finished with an 80!

Daniel Wolf’s private residence was located where the clubhouse is today, though his actual estate house burnt to the ground on July 18th, 2002. For the short while that Mr. Wolf enjoyed his course, he also let his house serve as a clubhouse for his private course. This view from the elevated tee makes the fairway some fifty feet below look narrow and yet the golfer has to swing out in order to cover the distance in the prescribed number of shots.

Why isn’t Royal Hague regularly associated with the great links in the United Kingdom as well as Europe? To start, it never enjoyed the fanfare that a design of this magnitude would normally receive upon opening. The start of World War II saw to that. In addition, the Jewish heritage of the owner Wolf necessitated a hasty departure from the country and he passed away in 1942. After the war, his widow sold the course to the then homeless Royal Hague and Sir Guy Campbell brought it back into playing shape. After that choppy beginning, five decades of largely unchecked growth by mother nature narrowed the playing corridors and limited the course’s visual appeal. Some of Alison and Morrison’s work was shrouded under dense vegetation and worse, altered by lesser architects. In 2004, the club wisely decided to return to its Golden Age roots with Frank Pont guiding them ever since. In particular courtesy of Pont’s work, all of the greens now feel as if they were done during the Golden Age. Presently, he and the club are successfully returning the course to its more open, sandier origins so well depicted in the black and white photograph found on the preceding page of this profile. Essentially, Royal Hague needs to be seen today as it is a markedly better course than at any point in the past several decades.

Harry Colt dominated golf in the Netherlands just as Tom Simpson did in Belgium. But in 1937, the older Colt wasn’t near the traveler that he once was and this project went to his two talented partners. When asked to comment on the difference between Royal Hague under the hand of them versus what might have been under Colt, Frank Pont notes:

Royal Hague is different from the other Colt courses in the Netherlands. First of all the bunkering is larger, deeper and bolder than on the other Colt courses. Not only that but very few bunkers were used on the course, only one fairway bunker and eighteen bunkers in total. This was less than half the bunkers that Colt would normally use on a course and a third of what he used at Kennemer. Furthermore the routing, and also the green locations were more adventurous, one might even say extreme, than Colt had shown in his work up to then. Royal Hague to this day remains a stern walk, and probably being a member there will add years to one’s life due to the healthy exercise.

As can be gathered from the quote above, Haagsche is a unique golf course and it doesn’t readily remind the golfer of any other course in the world. While enjoying a lovely jaunt through nature, the golf game is thoroughly examined from tee to green. Driving is both challenging and adventurous, iron play is demanding and all sorts of shotmaking is necessary to conquer the green complexes. This may well be the greatest canvas with which either Alison or Morrison ever were given. The age old hypothesis holds true here: Great property in the hands of great architects and an intelligent founder should produce one of the best courses in the world. And that’s exactly the outcome, as we are now freshly reminded.

What an environment in which to enjoy a game!