National Golf Links of America

NY, USA

Green Keeper: Bill Salinetti

Few views in golf rival the one from the 17th tee at National.

In the formative years from 1860 to 1905 of golf course architecture, the game was very fortunate to attract men who were filled with passion for the sport and who were willing to devote sizable portions of their life to the development of particular courses. Men like Old Tom Morris at Prestwick and then The Old Course at St. Andrews, Laidlaw Purves at Royal St. George’s, Willie Park at Huntercombe, H.C.Leeds at Myopia Hunt, Walter Travis at Ekwanok, Herbert Fowler at Walton Heath set standards prior to 1905 that any architect today would do well to emulate.

However,in 1906, golf course architecture was raised to an even higher level as so began Charles Blair Macdonald’s life long involvement with National Golf Links of America. Not immodestly, he anticipated that it would be viewed as his lasting monument. From the care he devoted to the selection of the property to the refinements he made to it over the next 30 years, he was determined to build the most noteworthy course outside the British Isles.

Others would famously follow, especially William C. Fownes continuing on from his father at Oakmont, Hugh Wilson at Merion, George Crump at Pine Valley, and Ross at Pinehurst No. 2 but Macdonald’s obsession with the strategic qualities of golf holes was revolutionary in the United States in 1909 when National finally opened for play.

Starting with his schooling years in St. Andrews in the 1870s and finalized with his 1902 and 1904 trips to the Great Britain, Macdonald gained an understanding as to what made some golf holes more special than others. He grasped that strategy makes holes as appealing to play the 100th time as the first, if not more so. Furthermore, he understood that sandy soil was a must for the ‘ideal’ course, that wind was crucial, and that the setting should be predominately treeless, as trees reduce the challenge by blocking the wind and providing depth perception.

Convinced of the merits of his convictions, he stumped around eastern Long Island in search for a site that would allow him to capture the playing qualities of the most famous holes that he had seen overseas.

Once he found what is today’s property, it didn’t take him long to spot a fine location for a Sahara hole from Royal St. George’s and an Alps hole from Prestwick, and a Redan hole from North Berwick. Not surprisingly, given his extended time in St. Andrews, The OId Course heavily influenced his thinking both directly in the Eden, Long and Road Hole versions he created and indirectly through wide fairways and large, rolling greens.

Thus, like The Old Course, The National Links remains to this day much more than a historical relic or museum piece – the dilemmas posed by its golf holes have never dulled. In fact, their timeless appeal highlights a strategic void painfully apparent in many courses built since WWII.

A primary reason that The National Links plays exceptionally well today is because of the work performed by its last two Green Keepers. Firstly, beginning in the late 1980s, Karl Olson began reversing several decades of neglect by clearing trees and brush, restoring fairway width and playing angles to the course, and recapturing lost bunkers and green sizes.

Then, with the full support of the club board behind him, Bill Salinetti, who replaced Olson on February 1st, 2003, has taken the course to the next level by focusing on how the course actually plays. Gone are the days where the fairways played slow and where practically the only way for a ball to end in a bunker was if it went in on the fly. Fast and firm playing conditions are the rule now with the ball bouncing every which way on both the fairways and the greens. When coupled with many ‘new’ vexing hole locations that haven’t been used in years, The National now has plenty of teeth. For instance, in the 2003 Singles which annually comprises one of the strongest amateur fields in the country, only three players broke the par of 73.

Set over a whopping 350 acres, the holes match the grandness of the rolling property and the golf here is bold and broad shouldered. The golfer feels like he can hit out as opposed to guiding the ball through narrow playing corridors. In the past decade, such architects as Bill Coore & Ben Crenshaw, Gil Hanse, Tom Doak, Mike Devries, Mike Strantz, and Brain Silva have returned to this fundamental concept of giving the golfer room to play.

Equally as impressive as the tee to green aspect of the course are its putting surfaces. At the point that Macdonald and Raynor commenced construction on The National Links, the finest greens in the country possessed more pitch/tilt than imaginative interior contours. With the greens at St. Andrews at the forefront of his thought process, Macdonald created a superlative collection of 18 putting surfaces. Similar to the ones on The Old Course, they are immense in size (some 170,000 (!!) sq. ft. in total) and run the full gamot from wildly undulating (e.g. the 1st, 6th, and 11th) to pitched to punchbowl to a few relatively flat ones (e.g. 9 and 17). The greens far and away surpassed any other than those at Oakmont that had been built in the United States when the course opened for play in 1909.

Holes to Note

First, 330 yards, Valley; One of the game’s finest openers, options are presented to the golfer straightaway: take a shorter club and go down the safer right side and face a blind approach or hit driver down the left and have a short pitch to the visible green. Of course, Greg Norman played it a third way: he blasted a three wood into the front left bunker, splashed out to a foot, and was off with a quick birdie. No matter which tact the player selects from the tee, he will eventually have to negotiate one of golf’s most severe greens, made so not by tilt but by savage interior contours. More than one player has taken a seven (including four putts) after driving within 60 yards of this green.

The ideal drive carries just past these bunkers and leaves the best look possible at the elevated green.

Otherwise, the approach from the right of the fairway is blind.

Impossible to capture on film, the two foot hump that the player is walking across is only a slight indication of the difficult interior contours found in the 1st green.

Second hole, 330 yards, Sahara; Bernard Darwin’s description of the Sahara 3rd hole at Royal St. George’s perfectly captures the merits of the 2nd hole here as well: ‘When a name (Sahara) clings to a hole we may be sure that there is something in that hole to stir the pulse, and in fact, there are few more absolute joys than a perfectly hit shot that carries the heaving waste of sand which confronts us on the third tee. The shot is a blind one, and we have not the supreme felicity of seeing the ball pitch and run down into the valley to nestle by the flag. We see it for a long time, however, soaring and swooping over the desert, and when it finally disappears, we have a shrewd notion as to its fate. If the wind be fresh against us, we must play away to the right for safety, and the glorious enjoyment of the hole is gone, but even so a good shot will be repaid, and every yard that we can go to the left may make the difference between a difficult and an easy second.’ Darwin was no longer around when the Sahara at Royal St. George’s was converted into a one shot hole in the 1970s (which is probably just as well!) but at least he would take delight in how this half par hole at The National Links confounds golfers to this day.

Third hole, 430 yards, Alps; Macdonald’s homage to the Alps at Prestwick is an improvement on the original as the drive holds more interest. The approach over the top of a fescue covered hill is one where it is difficult for the golfer not to look up and sneek a peek before he has completed the downswing. The 35 yard wide (!) green has some twenty yards of fairway in front of it, just enough room and margin of error for a long approach. The vast green is fiercely contoured and four putts can occur. The author considers the approach the game’s finest blind shot.

The ‘V’ shaped bunker on the far hillside is 250 yards from the tee with the green slightly to the left of that line and over the hill.

The approach to the 3rd is much more than just a blind shot, as it is to perhaps the boldest green complex on the course. This is the left portion of the green . . .

. . . and this is the right!

The view from behind the 3rd green with the fairway nowhere in sight.

Fourth hole, 190 yards, Redan; Of all the versions of the oft-copied Redan, this one is supreme thanks to a) its glorious natural location and b) its pitched green whose slope is severe enough to help the ball continue to roll while at the same time not too severe as to reduce the number of interesting hole locations. Interestingly enough, the high to low point on the green is a whopping five feet. In terms of routing, this hole represents a fine change in direction in a relatively straightforward out and back layout.

Does one start the tee ball at the right edge of the green and hook it down the length of the angled green? Or take the more direct path toward the red flag? A ten foot deep bunker gobbles up shots that are long.

Sixth hole, 135 yards, Short; One of Ben Crenshaw’s favorite short holes, the green is eccentric and a thorough original with nothing like it anywhere in the world thanks to a small mountain in the center which makes it effectively play as three small ones. A player on the opposite side of the green from the hole should happily take three putts. The front left corner of the green is quite good at gathering aball and feeding it into the front bunker.

The wild green contours of the Short hole are evident from the tee with the green’s sweep up to the left seeming to dwarf the golfer on the front of the green.

Seventh hole, 470 yards, St. Andrews: Macdonald’s version of the Road Hole is of similar length to the one in Scotland, which was considered a par five as recently as forty years ago. The green complex captures the merits/terrors of the 17th at St. Andrews better than any of the subsequent copies that Macdonald and Raynor made of the Roadhole. The bunker angled along the right and rear of the green is particularly noteworthy as it provides almost as difficult (though less unique) a recovery shots as the road on the original hole.

With the 8th in the distance, the relatively flat approach to the 7th reveals little of the trouble that lurks…

…such as the seven foot deep Road Bunker guarding the front-left portion of the angled green…

…and this even deeper bunker hugging the back right. Unlike most other back bunkers on Road holes which average only a few feet in depth, the steps leading into this one indicate its more penal nature, in keeping with the difficulty of the road at St. Andrews.

Eighth hole, 420 yards, Bottle; Fairway bunkers (i.e.bunkers that are surrounded on all sides by fairway) are a crucial componentto any strategic design. Yet, greater than 95% of the courses built since WWII don’t possess a single fairway bunker. Instead, modern architects placed the hazards on the sides of the fairways where they add little strategic value. Patterned after Willie Parks’ 12th at Sunningdale (Old) which opened in 1899, this strong two shotter is the only hole that Nick Faldo bogeyed on his tour of the course in 1986. An echelon of seven bunkers encroaches into the fairway from the lower left and effectively divides the fairway into a left and right portion in the landing area off the tee. While the right side may be the more direct route, the left side provides a more level stance and a better angle into the green.

This string of bunkers divides the 8th fairway into a left and right portion.

The left side of the 8th fairway is more elevated than the right and the green is oriented to an approach from this angle. The distinctive bunkers above are 15 paces from the front of the green.

Tenth hole, 460 yards, Shinnecock; Given National’s out and back routing, the golfer heads for home when he stands on the 10th tee. If he enjoyed downwind conditions on the front, then the back will be a tough battle into the wind. The fairway short and right of the green and the right-to-left slope of the green make for fun pitch shot (a common shot when into the wind). At over 10,000 square feet, the green is slightly bigger than an Olympic size swimming pool. Gil Hanse admires the green complex so much that he replicated it on his business card.

As bold as the design of the National is, many of its features are low profile and sit close or below the ground, as highlighted in this view from the 10th tee.

The direct approach to the 10th green must carry all the trouble but Macdonald did provide …

…plenty of room to the right as seen in this picture from behind the 10th green.

Eleventh hole, 430 yards, Plateau; The golfer has covered some thrilling topography to this point but the next two holes are over more pedistrian land. Macdonald knew exactly what to do though and the Double Plateau green created here and the steeply pitched green on the 12th are two of the most severegreens on the course.

The berm in the foreground hides the road (notice the white speed sign?) which bisects the 11th fairway. In between the berm and the Double Plateau green is the Principal’s Nose bunker complex, visible in the right center of the photograph above.

With the 11th green complex in a field, Macdonald needed to create interest. The Double Plateau green, with its two plateaus divided by a lower middle section, accomplishes just that. The day’s hole location is on the front left plateau, which is at least a 1/2 stroke easier than a hole location on the back one.

Fourteenth hole, 360 yards, Cape; The Cape hole is a Macdonald original, a strategic marvel the equal of any of the holes that he copied from Great Britain. The ‘bite off as much as you dare’ aspect of a diagonal carry remains as fresh today as it was in Macdonald’s day even though the aggressive line off the tee continues to slide to the right with advances in technology. As George Bahto points out, this present green complex and the one on the 17th are the only two non-original ones from when the course first opened. Macdonald shifted this green thirty yards backwards and inland in the 1920s when today’s entrance road was created in the 1920s (the 17th was shifted 35 yards back at the same time). Orginally, both the tee ball and the approach flirted with the same water hazard and indeed, that remains the accurate definition of a true Cape hole.

The thrilling diagonal carry off the tee has not diminished with time.

In true links fashion, the rolling 14th fairway rarely provides a level stance for one’s approach.

Fifteenth hole, 395 yards, Narrows; Robert Tyre Jones’s favorite hole, the 15th shares a common design trait with the other two shotters on the course: they play equally well downwind or into the wind. Macdonald’s design secret was not to seal off the fronts of the putting surfaces. Only in that manner is a player given the freedom to land a ball well short of the green downwind and conversely, hit a low runner for an approach when into the wind. That message was totally lost among architects from 1950 until Pete Dye’s first version of Crooked Stick and The Golf Club.

The view from the 15th tee captures both the 15th hole with its white flag just left of the tree in the middle of the picture and the 16th hole (the people are on that tee) as it swings uphill past the huge bunker.

The bunker in the right foreground is 60 yards from the front edge of the green and though it may not look it, there is actually 30 yards of fairway between the left bunker and the putting surface.

Note the proximity of the 16th tee to the 15th green.

Sixteenth hole, 405 yards, Punchbowl; Macdonald captured some of the fun and sporting spirit of the game when he designed this blind approach to a punchbowl green. Though Macdonald thought that Prestwick and Royal St. George’s had too many blind shots (‘more than three blind shots are a defect and they should be at the end of a fine long shot only’), he clearly liked the element of chance and mystery that a random blind approach shot afforded a course. His associate Seth Raynor would later build the ultimate Alps/Punchbowl hole at the 4th at Fishers Island.

Uphill shots are generally visually unappealing. Not so here, thanks both to the windmill and more importantly, the huge bunker that breaks up the slope and adds interest to the golfer’s eye.

This unique bunker is fifty yards shy of the punchbowl green. Note the directional marker in the background.

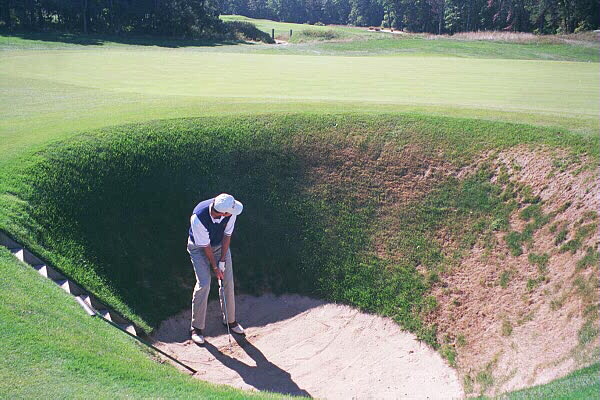

Seventeenth hole, 360 yards, Peconic; Playing angles abound off the 17th tee, with Macdonald doing little to guide the golfer as to how the hole should best be played. Should one go well right and flirt with the central bunkers in the fairway for the sake of a look at the putting surface? Or should one go down the middle and have a shorter though semi-blind approach? Perhaps downwind, the golferis willing to risk the longest carry off the tee in exchange for the best view of the putting surface? Of course, whichever decision one makes today, the odds are that the wind will be suchas to elicit a different decision tomorrow.

Should the golfer go long left, straight or to the right off the 17th tee?

This man didn’t quite make the needed carry for going long left.

The man who went right has this reasonable view of the 17th green, though he had to flirt with the central fairway bunker.

From this angle in the center left of the fairway, the white flag is barely visible through the grasses atop the sand ridge and the green is completely obscured.

Eighteenth hole, 510 yards, Home; Like the Home hole at St. Andrews, this one is not the hardest hole on the course but it is capable of producing swings of fortune. According to Bernard Darwin, ‘Finally, there is, I think, the finest eighteenth hole in all the world. The tee shot must be hit straight and long between a vast bunker on the left which whispers ‘slice’ in the player’s ear, and a wilderness on the right which induces a hurried hook. Then if the drive had been far and sure there is a grand slashing second to be hit over a big cross-bunker, and at last comes a little running shot at once pretty and terrifying on to a green of subtle undulations backed by a sheer drop into speakable perdition.’ And with technology having brought the green in reach in two for some (though that can involve throwing a ball out over the cliff and letting the wind bring it back), any score from a 3 to an 8 awaits, which is why it is such a favorite Home hole.

When play commenced in 1909, the course measured 6,100 yards and when Macdonald died in 1939, it measured 6,700 yards. Every hole had had something done to it. As Macdonald stated, ‘A first-class course can only be made in time. It must develop. The proper distance between the holes, the shrewd placing of bunkers and other hazards, the perfecting of putting greens, all must be evolved by a process of growth and it requires study and patience.’ A few tees like the 2nd and 8th have been since been extended and today’s course now measures almost 6,900 yards.

How then does Macdonald’s masterpiece stand up today versus the great courses built since its opening? Does it feature thrilling topography as at Pine Valley? Yes. Does the setting inspire like those at Pebble Beach and Cypress Point? For many, yes. Does The National Links feature width of play and enjoyment for all levels of golfers as at Royal Melbourne? Yes. Does it reward approaches from particular spots in the fairway like Merion? Yes. Does it enjoy an expansive feel like Sand Hills? Yes. Is the wind a key factor as at Royal County Down? Yes. Is there any disappointing aspect to The National Links? Yes, that subsequent architects evidently failed to appreciate many of its design merits.

In sum, does National Golf Links of America still deserve to be considered amongst the handful of greatest courses? Yes, absolutely. To quote Darwin again, ‘Those who think that it is the greatest golf course in the world may be right or wrong, but are certainly not to be accused of any intemperateness of judgment. The National Links is a truly great course; even as I write I feel my allegiance to Westward Ho! to Hoylake, to St. Andrews tottering to its fall.’

The End