Hollywood Golf Club

New Jersey, United States of America

Few North American designs rival Hollywood Golf Club in terms of the quality of its hazards and greens.

(Please note: GolfClubAtlas thanks Benjamin Herms for the use of his photographs throughout this profile. Please visit bhgolfphoto.com)

Since his 1899 collaboration with James Duncan at Ekwanok Country Club in Vermont, Walter Travis’s imagination was captivated by golf course architecture. However, his sterling amateur playing career (United States Amateur champion in 1900, 1901, 1903 and British Amateur champion in 1904) and then the founding of The American Golfer magazine in 1905 left him little free time.

So when Hollywood Golf Club approached him in 1916, Travis had only designed three eighteen hole golf courses. Nonetheless, the board at Hollywood clearly felt Travis was their man, in large part no doubt to his forceful writings in The American Golfer where he adamantly argued that hazards on most American courses were so poorly placed as to do little to challenge the tiger golfer. According to Travis, ‘A really good course should abound in hazards – and good courses develop good players.’

Hollywood was keen to convert their original 1913 Isaac Mackie design away from hazards that penalized the poor golfer and into a rigorous test for the better golfer. According to Bob Labbance in his Travis book entitled The Old Man, the club employed Seth Raynor ‘to correct some of Mackie’s mistakes’ but the end result remained unsatisfactory and Travis was contacted by the new green committee led by Frank B. Barrett.

From the start, the opportunity here in Deal, New Jersey must have appealed immensely to Travis as the sandy, 300 acre block of land was within two miles of the Atlantic Ocean. The property was not heavily treed (to quote Travis about his beloved Garden City Golf Club, ‘trees of any kind are nonexistent – as they should be’) and thus was exposed to the winds (quoting Travis again, ‘wind should always be an ever present factor’).

Reacting to the club’s stated desire for a first rate course, Travis stayed with Mackie’s general routing but gutted all of his greens and bunkers. In addition, he combined Mackie’s thirteenth and fourteenth holes into today’s superb thirteenth and created from scratch the long, difficult one shot seventeenth. With 250 bunkers of all shapes and sizes and a wild set of Travis greens, the course drew immediate praise upon opening in 1919. How good was it? Willie Rickie, the 1921 Met Amateur champion, considered it second behind Pine Valley, followed by Oakmont, Inwood, National, Lido, and Garden City. Historian Tom MacWood found an article in a 1926 Metropolitan Golfer magazine whereby Johnny Farrell rated Hollywood the second best course in the country!

MacWood notes that the green committee chairman Barrett deserves a fair share of credit for the final innovative design. A Vice President of a New York City construction firm, Barrett was the greens chairman from 1917 through 1930. MacWood points to Rickie’s observation that, “Hollywood is another course where the landscaping has had great attention. Hollywood in a sense is a monument to Frank Barrett as Pine Valley is to George Crump.” In addition, the New York Times wrote about Hollywood prior to the 1921 United States Women’s Amateur that, “Some of the holes, the creations of Frank B. Barrett, represent unique, almost radical, principles. There are two roads to every green, while the exceptionally large tees permit a variety of distances.” The article goes on to describe every hole.

Barrett worked hand-in-hand with Travis on the redesign and the result was a unique course that enjoyed an open, links feel with many cross bunkers.

Seriously, who has the guts to build bunkers like these?!

The bunkers at Hollywood come in all shapes and sizes. One of the largest guards the 11th green.

Often times though, it is the smaller, more peculiar shaped bunkers (such as the ones right of the 5th green above) that serve up the most awkward/testing recovery shots.

Of course, time can be cruel to ‘feature rich’ designs. It takes concerted effort, money and resources to maintain 200+ bunkers. As it was for many Golden Age courses, the period from 1940 to 1990 was tough at Hollywood. Tree plantings occurred and the bunker count was reduced in half. Travis’s playing angles became muted as the playing corridors became straighter and straighter. The course went from being open and linksy becoming a more conventional parkland course. The trees stunted the effect of the coastal breezes and led to soft playing conditions. Essentially, the course’s identity that Travis intended had been compromised.

As an appreciation for Golden Age architecture surfaced in the 1990s, the club called in New Jersey native Rees Jones. He seamlessly stretched the course to over 7,000 yards. In fact, the addition of several new back tees like at the third and fourteenth actually reduced the walk from the prior greens, which is always a neat feat. Trees were thoughtfully thinned, and some bunker patterns reinstituted. Additionally, Jones expanded a green like the 14th by 30% to recover some of its best hole locations.

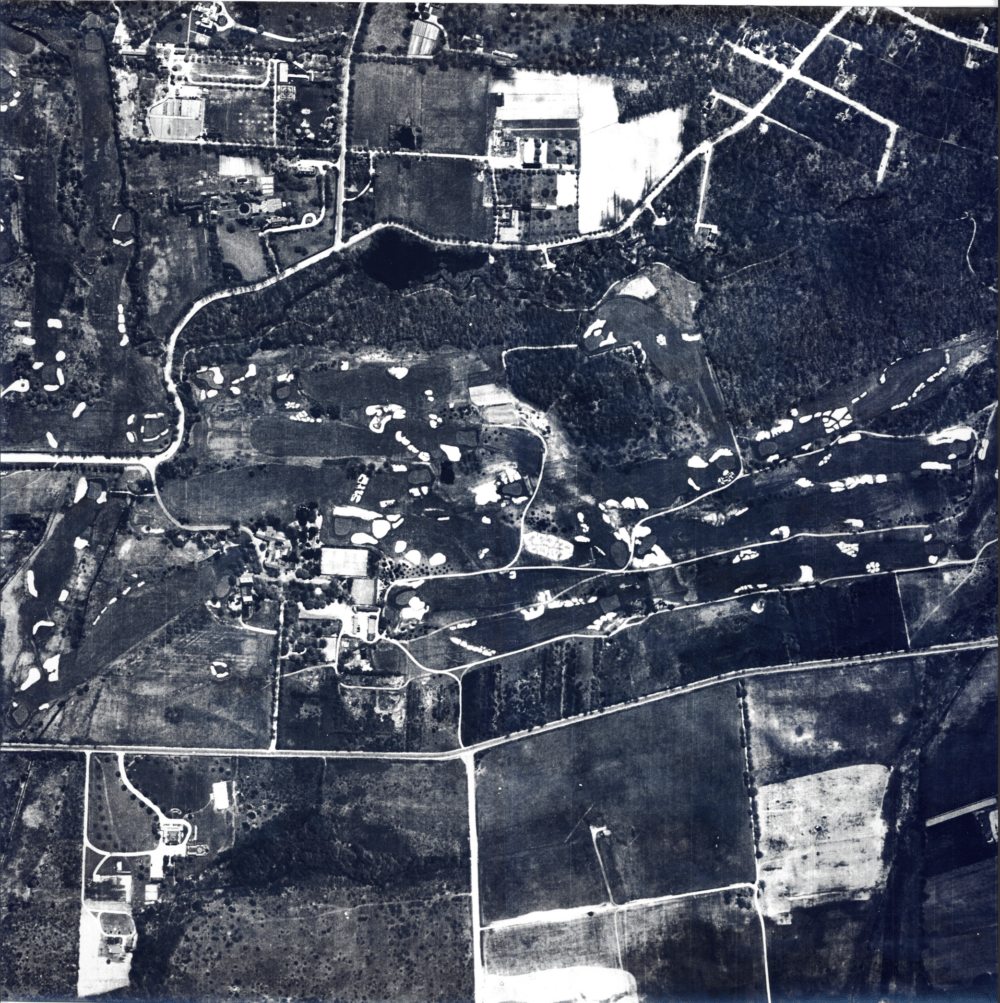

Move the clock forward another ~fifteen years and the level and quality of restoration work in America had greatly improved as the appetite at clubs for a faithful restoration expanded. Annoying features like cross bunkers were now being brought back as a matter of course. As it relates to Hollywood, a black and white 1940 aerial hung in the men’s locker room. Though the course was the best it had been for decades, it was apparent that it still fell well short of the course displayed on the wall. In 2013, the club hired Renaissance Golf Design to prepare the course, particularly its bunkers, to host the 2014 U.S. Women’s Senior Amateur.

This aerial in the men’s locker room has served as the road map for all work to the course since 2013.

Brian Schneider ran the project and personally reshaped every bunker. He had the aerial to work from which provided a 2-D perspective but he also benefited greatly from all the ground level photographs in the club’s possession from the 1921 U.S. Women’s Amateur, won by none other than Marion Hollins. Such photographs allowed Schneider to discern the height, and indeed the severity in some cases, that Travis intended for the mounds and bunkers.

Without doubt, Travis was an enormous admirer of links golf. As a relatively short but straight driver of the ball, he appreciated the penalties that pot bunkers meted out for errant shots. He fully embraced the concept that bunkers should be hazardous and were things to be avoided. That very ethos is what Schneider so brilliantly brought back to Hollywood. The bunkers here are some of the most pugnacious you can find and they come in all shapes and sizes per the black and white aerial. No guarantees are provided that you will enjoy a level lie, or an unrestricted swing or even that both of your feet will fit into some of these bunkers. Similar to what Travis saw overseas, sometimes, you simply have to play out sideways because the bunker walls and their associated mounds rise so abruptly. These are proper hazards, as Travis intended.

Hollywood is a thorough original. It is neither links nor parkland – it defies being neatly stereotyped, which is often times the mark of greatness.

As work progressed, and as one enticing feature was restored after another, the members became excited and the scope of the project increased. The goal became to return the course to the full glory as evidenced by the 1940 aerial. Give the club credit for letting Schneider do such a thorough, first rate job and for providing Schneider with whatever resources were required to see the project through to completion.

Thanks to Schneider’s hands-on approach, and the finishing working performed by Matt Hunter and Blake Conant, Hollywood’s eye-catching bunkering is once again drawing unstinting praise. Here’s the thing though: its greens are every bit as special. Schneider expanded them by ~15% and all the perimeter hole locations are once again back in play. Some greens like the ninth and sixteenth with its diagonal swale through it have to be seen to be believed. Bob Labbance wrote in his November 2000 Feature Interview on this web site: ‘There is no doubt that Travis wanted to test the ground game just as much as the aerial play, so special attention was paid to the subtle, yet perpetual movement of the green. Many times the slopes of the greenside mounds were reflected into the putting surface, and on every course there was one green with a substantial swale cut through it on a diagonal. So his greens were a challenging joy.’

These comments ring especially true at Hollywood. Be it at Cape Arundel in Maine or Country Club of Scranton in Pennsylvania or here, untouched Travis greens are standouts even by the high standards set during the Golden Age. Too many of his peers built sets of greens that sloped predominately from back to front. Max Behr sniffed that such greens acted as a catcher’s mitt. Travis imbued his greens greater variety, which comes as no surprise given what an outstanding putter he was. As per his Art of Putting, Travis treasured putting and his love for it shines through at Hollywood.

Every modern architect should study Travis’s greens for inspiration.

From Schneider’s perspective, this was a dream job. Travis’s work has always enthralled him and he considers Hollywood to be Travis’s finest work. After the tour below, you may readily agree! As you peruse Ben Herms photographs, note the perfect implementation of tall native grass areas. Their different colors and hues add delightful texture across the property while the sight of wispy grasses bending in the wind accentuates the links feel that Travis strived to replicate. Michael Broome, the club’s long time Green Keeper, deserves tons of credit and couldn’t be happier, remarking, “These naturalized areas contain grasses which require less water and fertility inputs while providing an aesthetically pleasing contrast on the golf course. They require almost no mowing and offer a cost savings in the long run.”

Hollywood has regained its open, expansive quality and the sight of the wind dancing across the property and rustling the native areas is one to cherish.

Holes to Note

Third hole, 460 yards; Variety is at the heart of great golf architecture and Travis delivered on that score at Hollywood with the placement and construction of his green sites. Consistent with courses built during the age of hickory golf, the greens of the long two shotters such as here, the sixth, and twelfth are open in front. In fact, the variety found across Hollywood’s collection of two shot holes is one design aspect that most impresses Schneider. As he notes, “Differentiating par 4s on a relatively flat site is hard to do. Travis got the most out of the ridge that runs through the middle of the property (including placing the steeply pitched third green at the base of it), just as he did in the far corner with his placement of the 11th green and 12th tee on a hillock. Elsewhere, his man-made features (e.g. bunkers and greens) lend variety to each and every two shotter.”

Herms’ photograph shows the interesting contours within the 3rd green as it rises five feet from front to back.

As seen above with the open 3rd green in the foreground and the elevated 4th green in the distance, Hollywood offers an intriguing mix of ground and aerial approach shots.

Fourth hole, 150 yards; A completely manufactured hole, and none the worse for it. To accentuate the perception of the course as links-like, Travis built faux sand dunes on the main ridge that divides the course into east and west sections and sandwiched the green between them. Travis also put a sea of sand in between the tee and the green to emphasize the hole’s coastal setting but that sand has since been removed. Still, the six bunkers cut into a pair of artificial hillocks – with two of the bunkers well above the green itself – is unique in world golf. Most love it, and a few hate it, but there is no denying that Travis the architect had the imagination and daring to create highly memorable holes.

Just carrying the bunkers isn’t good enough – a false front readily sheds weakly hit balls.

The shortest hole on the course is also one of its most distinctive.

Sixth hole, 425 yards; Hollywood occupies a block of property that is predominately rectangular with many of its holes running along a east/west axis. When the wind blows off the ocean, the third, fifth, sixth, ninth, tenth, and sixteenth play downwind while the first, seventh, eighth, twelfth, fourteenth, and eighteenth stretch out as they play into it. Obviously, the reverse holds when the wind blows off shore but either way, a hole like the sixth plays equally well because Travis left the green open to accept a wide variety of approach shots. Deep, or rather tall, fairway bunkers punctuate the right side while the green’s false front is but the first challenge that the golfer must contend with on his approach. In order for the course to play properly, the fairway areas leading up to the greens must play firm as Travis’s design intent would be undermined if the approach areas were soft. In that regard, Green Keeper Michael Broome and his crew have been aces. Since arriving at Hollywood in December, 2009 from Saucon Valley Country Club, Broome has set about firming up the playing surfaces on a daily basis. According to Broome, focus is on “the constant addition of sand to aid in the breakdown of the thatch that had accumulated. We constantly perform vertical mowing to physically remove the thatch from below the playing surface. Importantly, some of these key areas before the greens are exclusively hand watered to insure that they don’t receive any more water than is absolutely necessary. Slowly but surely, we have removed the thatch that produced the spongy, mattress feeling from some of the playing surfaces.” Just look at the green below and imagine all the fun outcomes from seeing a ball climb onto the putting surface and interact off the flared humps found left, right and behind.

Built in a field, the push-up 6th green is a thing of artistic beauty. In fact, Schneider was so captivated by it that he borrowed design cues from it when he built Old Barnwell in South Carolina. Oscar Wilde was right when he wrote, “Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery.”

Seventh hole, 540 yards; The kind of green complex that is curiously rarely found today, this one is angled in such a manner as to best accept shots from a certain position in the fairway. An oval shaped green simply doesn’t offer as strategic a target as this green complex does and yet, sadly, golf is more full of the former than the later. Such a green as here – and considering it was built in 1918 – is but another sign as to how innovative Travis was as a course designer. Pete Dye subsequently used such a ploy and angled many of his best par five green complexes (e.g. the seventh at The Medalist, the eleventh at The Honors Course, the second and sixteenth at Kiawah’s Ocean Course, etc. ) but too few other architects have followed the lead established by Travis over a century ago.

As seen from behind, look at how the angled green makes the long 7th play anything but straight.

Twelfth hole, 460 yards; A spectacle from the tee, this hole once had fifty-seven bunkers on it (i.e. this single hole had more bunkers than the entire course at Augusta National when it opened!). A majority of the bunkers remain to this day. Travis wasn’t a long hitter but he was accurate and this hole favors such a person. Only the man who hits the fairway can have a go for the green in two by carrying the nest of cross bunkers that are 100 yards short of the green for his second. Not surprisingly given that this hole heads straight toward the Atlantic, the last seventy-five yards in front of the green is wide open. Travis clearly is giving the golfer every opportunity to hit a low wind cheater, a shot that he thrived on when he won the 1904 British Amateur at Royal St. George’s.

Travis seized upon the highest point on the property to build the spectacular ‘Heinz 57’ hole.

Once off the tee, the rest of the twelfth is played over flat land so Travis used a multitude of bunkers to give the hole its golfing character. Notoriety soon followed.

As seen from behind, the indentation in the front of the green makes back right hole locations difficult indeed.

Thirteenth hole, 335 yards; A clever dogleg left where it is most helpful to know the day’s hole location before hitting one’s drive. If it is left on the somewhat V shaped green, the golfer wishes to drive long right to the outside of the dogleg. Complicating matters is the newly restored Principal’s Nose bunker configuration of three small bunkers seventy yards short right of the green. Conversely, if it’s right, the golfer ideally positions himself shorter off the tee and closer to the inside of the dogleg. Regardless, the hoped for birdie never seems to materialize as often as one might wish on a hole of this length. For any course to be considered great, the requirement for finesse is essential and this hole is a sterling example of that need being met.

The pitch to the 13th needs to be well judged as the green is the smallest target on the course. As recently as 2005, a wall of trees framed the green, depriving it of needed sunlight and circulation for a healthy playing surface.

This view from behind shows the central hazard that lurks back in the fairway.

Fourteenth hole, 440 yards; Thanks to tees being moved back by ~ forty yards at the third, sixth, ninth, twelfth, eighteenth and here at the fourteenth, the two shots holes at Hollywood are just as strong today as they were in Travis’s day of hickory golf. Given that the golfer knows that a stream fronts the green, the pressure is on for him to get away one of his best drives of the day. Only by avoiding the large bunkers off the tee and finding the fairway does he entertain any notion of carrying the fronting diagonal hazard and reaching the green in two. Regardless, the real trick is to hit a crisp iron off a sloping, downhill lie and not chunk one into the fronting creek.

At the 14th, a creek slashes across the front of the green, which squarely places the emphasis on finding the fairway from the tee. Even if successful, forward hole locations remain exasperatingly difficult.

Sixteenth hole, 475 yards; At the time that Hollywood opened, only Oakmont and Pine Valley (depending on how one classifies a ‘bunker’) had more hazards in the United States. Over the ensuing decades, various bunkers were filled in, sometimes because they didn’t really influence play with modern equipment and other times because they were too well placed, meaning they got under everyone’s skin! Such was the case here where the feeling became that diagonal bunkering in from the right was too punitive when combined with Travis’s infamous volcano complex on the left. Well, Travis certainly didn’t think so – and that was in the days of hickory golf. Happily, strong leadership at the club greenlighted Schneider to restore the bunkering scheme on this 1/2 par hole. With Travis’s cross hazards back at full roar, the sixteenth is another example whereby the golf at Hollywood can be played in a zig-zag manner even through the playing corridor is straight.

This 2010 photograph highlights how Hollywood was well regarded at the time but also how it failed to live up to its full potential. First, it shows the course when it was wall-to-wall green and more heavily treed. Second , it showcases Travis’s one-off famous ‘volcano’ bunker down the left. Third, when compared with the 2021 photograph beneath it, it shows how Travis’s other cross hazards had been neutered.

The newly installed diagonal bunkers that encroach from the right are 90 yards from the green.

Back in the late 1910s, the club decided they wanted hazards that were more in play – and that’s emphatically what they got when they hired Travis. At under 500 yards, this is a great swing hole in a tight match. Note the high back left plateau, as well as how balls can be whisked off the green’s right side.

Seventeenth hole, 195 yards; This hole was a Travis special, utterly unique in golf, and he created it from scratch. Yet, over time, it had been completely altered, leaving behind scanty little that Travis would recognize. However, in 2013, the club wasn’t quite ready to do everything required. Rather than take half measures, Schneider proposed that they wait. In the winter of 2021, the green light was given for work to proceed. Yes, a few other important features remain to be installed (such as the cross hazards 60 yards short of the third green) but this was the final major piece of the restoration puzzle to fall in place. Now, there aren’t many course critics who don’t have Hollywood comfortably in the top five courses in the golf rich state of New Jersey.

A necklace of bunkers surrounds the fairway that flows onto the open 17th green.

Golfers don’t often walk through a tunnel to reach a green.

Never a dull moment putting on the 17th green.

Eighteenth hole, 445 yards; A little over an hour up the Garden State Parkway in Springfield, New Jersey, A.W. Tillinghast built some of the best holes at Baltusrol on the Upper Course. Holes like the fourth and fourteenth aren’t among the heaviest bunkered on the property as they didn’t need to be: Tillinghast let the topography present much of the challenge. Such holes simply weren’t possible on the flatter Lower course so Tillinghast resorted to man-made features (i.e. bunkers) to provide its playing interest. Similarly at Hollywood, the modest rolls throughout the property meant that Travis largely had to create the golfing quality in each hole. Hence, his final design was heavily bunkered but more importantly, all the bunkers (coupled with the greens) meant the course was chock full of character despite being routed over modest topography. Like Tillinghast, Travis prided himself in knocking character into each and every hole and the strong eighteenth caps off the course in a fitting fashion. One can readily imagine Travis hitting another of his laser straight drives, then likely hitting to the green first and holing a putt with his magical center-shafted Schenectady putter, assuming of course that he hadn’t closed out his opponent well before!

The 18th concludes a design without a single weak or undistinguished hole, a great tribute to The Old Man’s architectural prowess and imagination. How much additional putting surface Schneider captured is evident in the photograph above.

Congratulations to Hollywood for the strides made this century in returning the luster to this important and highly regarded design. Working closely with greens chair Frank Barrett, Travis poured a tremendous amount of thought and creativity into this design with the result that it makes 99% of other courses look positively banal. When Vardon, Ray, Barnes and Hagan played their famous series of matches across the United States in 1920, they agreed as to their favorite venue. Yep, you guessed it – Hollywood.

Hollywood’s men locker room houses the all-important 1940 aerial, from which so much good has come.

(Thank you again to Benjamin Herms for the use of his photographs throughout this profile. Please visit instagram.com/bh.golfphoto for more of his work.)

The End

![The Park, West Palm (Lit 9) [2023]](https://golfclubatlas.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_7092-2-scaled-500x383.jpg)