George Wright Golf Course

Massachusetts, United States of America

One of Donald Ross’s mightiest accomplishments was the design and construction of the George Wright Golf Course for the City of Boston. The view above is across the third green to the one-shot fourth.

How a city looks out and provides for its people helps define that city’s culture, if not its soul. Providing a beautiful environment for its citizens to enjoy several hours outdoors is a most noble cause with far reaching benefits, both tangible and intangible. With its copious parks and nature trails and yes, high quality golf courses, no city is doing it better than Boston right now.

One example of a wonderful golf facility available to all is the open and expansive Franklin Park where Bob Jones honed his skills. In fact, this followed Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx to become America’s second public course. Guess who helped create it in 1896? The legendary sports figure George Wright, known for a multitude of accomplishments including his hall-of-fame play at shortstop and founding Wright & Ditson Sporting Goods (where Francis Ouimet worked as reigning US Open champion!). Several decades later Wright also helped orchestrate the donation of 156 acres from the Grew estate to the Department of Conservation of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts with a sole contingency that the parcel be preserved as open green space.

That land is now occupied by a golf course that proudly bears his name, yet that the old Grew estate would be used for golf was not always a given. Indeed, an attempt to create a private club had failed just before the onset of the Great Depression. Frankly, the terrain was ill-suited for golf, dominated by granite and pudding stone, giving way to the occasional low wetland areas and void of much topsoil.

Initially, before the land was given to the City, Ross laid out a course for a group of investors intent on a private club. The Great Depression hit and the investors were gone. Shortly thereafter the property was left to the City of Boston, and the City’s political leaders decided to build a golf course using Ross’s design. The City told Ross they could dedicate $250,000 to the effort. Yet, Ross knew that dynamiting would be required to transform the ledges and boulders into something good for golf. Additionally, twelve inches of topsoil were needed to cap the property. Ross informed the City that it would cost $1,000,000.

Imagine his surprise when the City came back – thanks to a bond and Franklin Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration – and said they were ready to go!

Walter Irving Johnson oversaw the massive undertaking. According to the City of Boston’s web site, ‘Before completion, 60,000 pounds of dynamite were used to excavate the ledge, 72,000 cubic yards of dirt were spread to raise the ground above the swamp level and 57,000 linear feet of drainage pipe were laid to keep the property dry. The WPA provided the funds to build the course, estimated at $ 1,000,000 for completion in 1938. At one time 1,000 men worked on the project.’

Give the City credit: the undertaking was first rate. Solid brass irrigation heads were installed. Drainage pipes as wide as 30 inches (!) were utilized and made of good old fashion, American steel. An impressive, nearly three mile long stone wall enclosed the property, courtesy of Boston’s Italian and Irish masons. To cap it off a gorgeous clubhouse reminiscent of a French Chateau was constructed for $200,000. Lore suggests that this was done at the request/order of then Mayor James Michael Curley, known as the Irish Robin Hood. He was a hero to the poor and had recently returned from France impressed by that country’s architecture.

Ross’s construction chief Walter Hatch had quite the challenge. Dynamite was necessary to create fairways like the third, fifth, sixth, eleventh, fifteenth and sixteenth. This was so artfully done that the golfer won’t know the how but simply marvel at the New England topography and happily assume that he is playing past an occasional rock outcropping like those found at The Country Club in Brookline just eight miles away. Jagged granite stones, the size of softballs, are found under many of the well-draining green pads.

The conditions in Boston were certainly a far cry from those that Ross enjoyed in the Sand Hills of North Carolina! As such, the George Wright Golf Course enjoys a drama that comes with such a rugged environment but the greens lack the nuanced contours that come from working in sand as opposed to clay.

The foreground tells the story of the difficulty in building the course while the handsome background of the seventeenth green complex demonstrates the appealing end result.

When it opened in 1936, the course, barren of trees, quickly gained a fine reputation even among the high quality private venues in golf-drenched Boston. However, World War II, unchecked tree growth, a series of financial crises, poor management and, lo and behold, the course became a mess. In the 1980s the City almost allowed it go fallow due to budgetary constraints but the Massachusetts Golf Association did what golf associations are supposed to do and fought hard for the interests of the game and golfers. The course remained open for another twenty years.

Move ahead to the year 2002. Head Professional Scott Allen came on board and started clamoring for change. The course was in such disrepair that the greens were nearly unputtable and half of the irrigation heads no longer functioned. Contracted maintenance had slumped to the bare minimum and fortunately the City decided to take a different tack. In 2004 entered Len Curtin, son of the long-time Green Keeper at Stiles & Van Cleek’s Robert T. Lynch Municipal Course that abuts The Country Club. Curtin grew-up in and around Boston golf. A crack player, he worked on the green crew at The Country Club during Curtis Strange’s U.S. Open win.

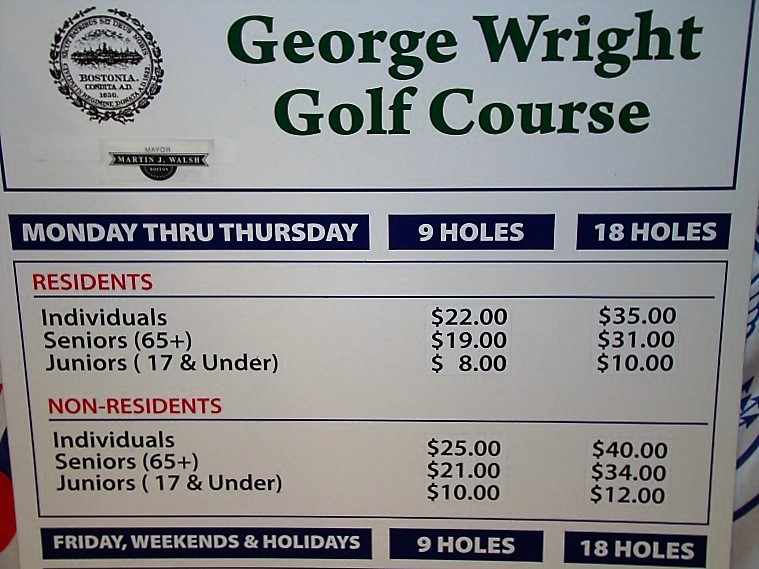

When the City called, Curtin was employed at Lexington Golf Club, which has a proud history dating back to 1895. What impressed him about the opportunity was the City’s commitment to fix George Wright, a place that he adored and where he had grown up playing. The City pledged that the revenue generated from the facility would stay put and be re-invested into the facility. This unusual assurance has proved steadfast, largely driven by the late, beloved Mayor Tom Menino whose dedication toward establishing a policy to restore the course, facility and surrounds continues to this day with Mayor Marty Walsh. Look no further than the current, ongoing massive overhaul of the clubhouse as proof.

Curtin began a slow, methodical program to peel back decades of neglect. Like all courses shrouded from sunlight and air turf conditions were patchy and root structure weak. Job #1 was to improve the quality of the putting greens. This he accomplished in the first few years, aided by the removal of huge trees from the green surrounds. Examples include the sixth and tenth and especially the eighth where forty oaks had robbed the hole of its majestic character. During his second five year stint quality turf was returned to the fairways and tees.

Along the way Curtin collaborated with Massachusetts golf course architect Mark Mungeum. Bunkers were added for today’s ball and were built in a manner sympathetic to Ross. How good is George Wright now? The Massachusetts Golf Association awarded the 2018 State Amateur to the course; the first time this prestigious event will be contested on a “muni.” It’s hard to imagine a greater compliment but listen to the passion the course stirs in local player and filmmaker, Cob Carlson. He began playing there in the mid 1990s and has had a front row seat to admire Curtin’s work. In 2002, Carlson won the Club Championship and wrote:

I have been playing the George Wright Golf Course for the past twenty years. I was introduced to the place while playing in a Friday afternoon co-ed league with fellow workers from WGBH, the flagship PBS station in Boston. For reasons that I still try to identify the George Wright Golf Course gets into your blood and you come back again and again to test your golfing mettle. I say that having played in state tournaments run by the Massachusetts Golf Association for years, which had allowed me to become acquainted with some of Ross’s other great courses … Plymouth, Concord, Essex County, Winchester, The Orchards, Whitinsville, Pocasset, Ponkapoag, Weston, and Charles River, to name a few. After Len’s work I feel the same mysterious thing when I play George Wright: it just feels right and I was enveloped with a sense that this is how golf was meant to be played.

Carlson goes on to credit George Wright for providing him the gumption to self-fund and complete his two hour film entitled Donald Ross: Discovering the Legend (www.donaldrossfilm.com). He remains in awe that such a quality course exists for one and all to enjoy:

In 2005 I floated an idea to ESPN, NBC, and the Golf Channel to do a film on the great golf course architect. I had hoped to have it coincide with the 2005 U.S. Men’s Open at Pinehurst No.2. None of the networks were interested so the idea went to the back burner. Flash forward eight years. I continued to play George Wright and by this time, after hundreds of rounds, had become intimately familiar with it. A voice would occasionally pop up in my head …”don’t forget, you need to do a film on Ross…” The 2014 U.S. Opens were to be played at Pinehurst, so it if the stars would align, I could finally produce the film. What pushed me forward? First and foremost, it was the deep love I have for the tiny masterpiece Ross had crafted that I proudly call my home course.

What an accomplishment that a municipal course can inspire someone so passionately! If you want to know how golf can attract new blood to the game, look no farther than the George Wright Golf Course. See if you agree.

Holes to Note

Third Hole, 525 yards; The first two holes head away from the stately clubhouse and homes dot the right perimeter. However, when the golfer steps onto the third tee, he turns his back to the homes both figuratively and literally. He won’t see a man-made disturbance save the clubhouse and maintenance area until the sixteenth tee. Such solitude is shocking, given that the course is but five miles from downtown Boston! Part of the old Grew estate, the 475 acre Stony Brook Reservation and its old growth forest dance alongside the middle of each nine and help cocoon the course from buildings and noise.

Fourth hole, 165 yards; There are several features at George Wright that command comparison with Ross’s finest works and one is surely an outstanding set of one-shot holes. Carlson notes, ‘The one thing I have learned from hundreds of rounds, many in competition, is that you must play the par threes well. Bogies flow freely at the quartet of them and when you add in some very difficult par fours … 5, 7, 9, 10, 12 … good golfers are often left wondering how they scored so poorly on a course that measures barely 6,500 yards.’

The fourth plays across a valley to a shelf green. Curtin and his crew have extended the green back to its edges. In so doing they recaptured the false front, which sends many a tee ball trickling back toward the tee.

Fifth hole, 410 yards; Set along the high point of the property, the fifth’s playing corridor elbows right in an attractive manner allowing each golfer to pick his own line. Bouncing one’s approach onto the putting surface that’s nestled in a dip is one of the most satisfying shots on the course. According to Carlson, ‘The roller coaster dogleg right fifth features the most challenging tee ball on the course. The ideal play off the tee may be a three wood, five wood, or 3 iron with a slight fade. This puts you in the neighborhood of 200 yards with a somewhat blind approach shot that plays shorter because there is a steep drop-off just before the green that allows you to land short and bounce your ball onto the putting surface. However, those bounces can send you in a myriad of directions including long over the back of the green. Can you fly it on? Yes, but it must be with a very high trajectory or the odds are your ball will be propelled over the back. Some players hit driver and choose an aggressive line over the trees on the right but you must be absolutely perfect. If you are, you will have a nine iron in. Miss right and you will be chipping back into play because you’re blocked by trees. Hit left and you’ve gone over a rocky ledge and are likely looking at double bogey. As I said, the smart play is to the top of the hill where the dogleg begins. Take your par and run.’

As seen from behind, the downslope twenty yards prior to the putting surface can be used to the golfer’s advantage.

Sixth hole, 395 yards; Carlson’s especially admires this hole’s meandering fairway and how Ross draped the green over a ledge. The back half of the putting surface actually falls away. Carlson explains, ‘The sixth hole is my favorite hole on the course. If readers watch my DVD extra “Scott Allen…” you will hear why. I love it for its subtlety. Basically it is a straight hole, but Ross winds you from tee to green in an elegant ‘s’ curve that requires you to think hard about the different angles you might take to approach the green.’

Cob Carlson film excerpt: Scott Allen on the Sixth

Though the playing corridor is straight, Ross swung the fairway well right of the direct line to the flag. The golfer is oblivious to the dynamiting that occurred here.

Seventh hole, 400 yards; Holes set over tumbling land have the ability to confuse and confound. Here, a steep drop in the fairway occurs 220 yards from the back markers. Plenty of golfers blast away from the tee, intent on hitting the fairway to enjoy a big kick toward the green that leaves a mere short iron. The rub is that such tactics leave the golfer in a valley playing an approach over a ridge to a fluttering flag but hidden putting surface. Curtin, who played off a 1 handicap in high school and college, suggests restraint. He prefers laying back for the sake of a good look at the green and then playing a low punch shot. Especially when the flag is center or right, the ground in front of the green is adept at pushing such an approach toward the hole. As always, Ross makes the choice – yours.

… or not lay back off the tee, that is the conundrum! Seen above is a much shorter shot but the putting surface is blind and the golfer might well have to contend with a slight downslope. The second green is in the distance.

Eighth hole, 185 yards; Curtin’s handiwork shines here. Ross placed the green on top of a hill with a dramatic embankment left. A golfer wouldn’t have known that in 2005 when the bank was overgrown with trees and brush. Today’s uphill shot is the same as it was ten years ago but the sense of accomplishment and the appreciation for the landscape is greatly accentuated. Without the trees Curtin was able to reclaim a good six feet of putting surface along the left and restore many of the green’s most taxing hole locations.

Ross had a knack for building uphill par 3s that both play and look great. Examples abound in the Northeast and include this one, the 12th at Wannamoisett and Essex County’s 11th.

![]() Cob Carlson film excerpt: Len Curtin

Cob Carlson film excerpt: Len Curtin

Tenth hole, 460 yards; While the layout occupies an ample 145 acres, Ross didn’t have gobs of extra room with which to work but the varied shot requirements that his usual clever routing yields are evident in spades on the second nine. Nine and ten measure over 1,000 yards (!) and these back-to-back holes are the biggest two-shotters on the course. A dogleg left was placed here with a long downhill approach to an open green and is complemented by the sharply uphill tee ball at the dogleg right eleventh. These alternating requirements help explain the glowing affection this place engenders in people like Carlson.

A majestic oak tree makes its presence known down the left; best to approach this bunkerless green from the outside of the dogleg.

Eleventh hole, 360 yards; This dogleg right folds neatly inside the elbow of the tenth and while considerably shorter still bristles with challenge. Like the sixth it is an example of a rugged hole that feels entirely natural even after tons of dynamite were used to lower the landform in the driving zone. The tee ball is well uphill but appears natural and not so excessive that it doesn’t constitute good golf. Ross never encountered granite in Pinehurst, so it’s clear that the three decades of experience that the Maestro gained in building courses in New England prior to George Wright came in handy.

A leftover granite outcropping serves as a perfect target for the most uphill tee shot on the course.

The intermediate size green is one of the harder targets to find on the course. Like the fourth, Curtin’s green expansion allows balls to release and bleed off the front right, down into the gathering greenside bunker.

Twelfth hole, 410 yards; A polarizing hole that some embrace for its edge-of-the-world playing attributes and others bemoan as unreasonably penal. There is no hint from the tee what lies ahead because a 35 degree embankment bisects the fairway creating a steep drop-off that has been maintained as rough since Ross’s day. All for good reason: it is well nigh impossible, not to mention impractical, to maintain it at fairway height. Do you try and blast beyond it off the tee – or lay back?

This view from behind provides an accurate sense of how the twelfth plummets downhill and a good view of the rough covered embankment that has frustrated golfers since the beginning.

Fourteenth hole, 190 yards; Almost everyone familiar with the course singles out this one-shotter built on top of slabs of granite. Here the golfer experiences the only long green-to-tee walk on the course as he climbs a good forty feet from the thirteenth green. Unlike many modern courses where such extra effort to reach a tee isn’t a rewarding experience, it is here. A false front left and a green that sneaks right around the shoulder of a hill provide all sorts of interesting hole locations. Wider than it is deep, the green calls for one of the most accurate iron shots of the day. A decade ago, the green was a small oval and a boring target. Curtin is especially pleased with how they have recaptured the playing attributes of Ross’s greens across the course. He elaborates, ‘Our greens had shrunk to about 60% of their original size due to years of indifferent maintenance practices. I am very proud of being able to find the original rectangular shapes of our greens, and re-establishing the false fronts on most of our greens that is so typical Ross. This would not have been possible without the help of long time member, former club champ and all around terrific guy, the late Billy Mathews. He really showed me where the original footprints of all the greens were early post WWII. Billy was a living, breathing George Wright encyclopedia, and I leaned on him all the time.’

A false front and a drop-off long define the task from the tee. The author only wishes that the massive 50 ton granite boulder in the background (but off the course’s property) could be better seen and appreciated.

As seen from the left of the green, the Stony Brook Reservation beyond the stone wall shelters this portion of the property from outside disturbances.

Seventeenth hole, 170 yards; Most Ross courses had their genesis in the age of hickory golf. Not George Wright, steel shafted clubs had firmly taken center stage by the time the course was built. Additionally, the sand wedge had become standard armature while most hickory sets ended with a niblick (the equivalent of a nine iron). Aware of these evolutions, Ross adjusted his demands on the golfer and this exacting one-shotter is a prime example. Considering that the course was built for the public, the author doubts Ross would have required a such a long aerial approach over deep fronting bunkers in the hickory era. Another eight decades of equipment advancement has not diminished this penultimate hole’s charms and challenge.

Watching a well-struck tee ball clear the front bunkers, climb the back slope that Ross flared (Curtin restored) and return close to the hole is one of the indelible memories from a game here.

Eighteenth hole, 380 yards; Given George Wright’s elaborate construction, comparison can be made to Seth Raynor building and dynamiting his way to glory at the Yale Golf Club. Such an analogy ends at the seventeenth where the holes proximal to the clubhouse, the first, ninth and eighteenth are on flatter portions of the property. The home hole isn’t savagely played up and over a mountain à la Yale but rather more gracefully on tamer terrain. Regardless, appreciation for these two master architects is enhanced by touring both courses. While they always got the most out of a site, when they weren’t blessed with natural features, they knew exactly what to do – and what not to do – to end up with creations that feel deeply rooted in nature.

There you have it! What a round, what a place. From Head Professional Scott Allen’s warm greeting to the amazing recovery that Len Curtin has achieved on a limited budget this place reeks of the spirit of another famous municipal course – The Old Course at St. Andrews. Everyone is welcome; it’s just that the golf is more affordable here! No better incubator for the game’s long term health exists than the municipal golf course. As such, the revival of Georg Wright is one of the game’s most compelling stories. Much can be gleaned from understanding this story as it serves as an enlightened path forward.

Accolades abound for George Wright, Ross and Hatch, Roosevelt’s wisdom, the City of Boston and some of its great mayors, and to no less a degree, Len Curtin. If you know someone who lives in Boston who doesn’t sing the praises of this course, then you know a fool, a snob or worse.