French Lick Resort (The Pete Dye Course)

Indiana, United States of America

Whether you look to the west over the first nine or ….

… to the east over the second nine, the majesty comes through of the Pete Dye Course located atop Mount Airie in southern Indiana.

Pete & Alice Dye’s careers in golf course design started in 1955 in Indiana. For ten years, they worked primarily within the state, from tinkering with the Country Club of Indianapolis, to building a nine hole course now called Royal Oaks, to building their first eighteen hole course on eighty acres at Heather Hills for the design fee of $8,000, to Brazil and Monticello. What a ride it has been! To this day, they live off the eighteenth fairway at Crooked Stick in Indianapolis, a course they refer to as their firstborn. Surely fifty years ago when their journey began they could not have imagined that they would one day move as much dirt and have an open checkbook to build a course like no other as they did in rural southern Indiana for Mr. Bill Cook.

Since Crooked Stick opened in 1966, much has changed with the game. Gone are persimmon heads and blades with golfers now wielding 460cc exotic metal heads heads and cavity backed irons with enhanced sweet spots. Players shape the ball less and swing harder and the Dyes have had a front row seat to how equipment has altered the way the game is played. Along the way they witnessed the 1991 PGA Championship famously won by ‘Long’ John Daly in literally their own backyard. As Pete Dye put it in Bury Me in a Pot Bunker, ‘Over four days John demolished my golf course.’ A monster hole like the dogleg left fourteenth was reduced to a flip sand wedge approach by Daly. In 1994, Dye saw Greg Norman eat up TPC Sawgrass with a winning total of 24 under par. Most recently, Fred Funk shattered the USGA scoring record at Crooked Stick while capturing the 2009 Senior Open at 20 under par.

How would you react as an architect? These were never intended to be push-over courses! Indeed, the Dyes optioned the 400 acres that became Crooked Stick because they were sure that Indianapolis would support a golf club centered around challenging the stronger player. In the mid 1960s, it nearly reached 7,000 yards in length, considered more than ample at the time. In 1990, Dye built a set of tees for The Ocean Course at Kiawah that measured 7,600 yards – and people thought he was crazy. His intent for Kiawah was that an expensive design built expressly to host big events not become obsolete in his lifetime. Sure enough, twenty years later as Kiawah prepares to host the 2012 PGA Championship, all of the back tees well be considered for use on a daily basis with the expected winds.

The progression of Dye’s career – from Crooked Stick to The Golf Club to Harbour Town to Casa de Campo to Oak Tree to TPC Sawgrass to Long Cove to The Honors Course to Blackwolf Run to The Pete Dye Golf Club to The Ocean Course at Kiawah to Whistling Straits – is remarkable on several levels including longevity and innovativeness. In considering this headline list of courses, one is struck by the high quality (the majority of them deserve to be included in any talk of world top 100 courses) as well as how none reminds one of the other. For five decades the Dyes have continued to push the envelope with their creations, always coming up with singular designs.

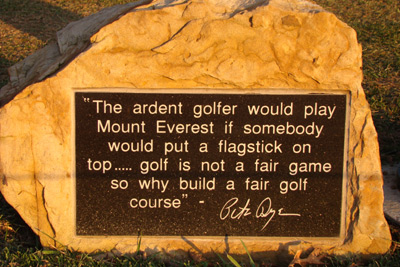

Many professionals gnash their teeth at having to face one of their courses. As Dye notes in Bury Me in a Pot Bunker, ‘Silence may be golden and accolades cherished, but unless a few golf professionals are bellyaching about my course design, I wonder whether I’ve done enough to challenge them.’ The comment is a telling one because it is centered upon the good player. As both Pete (he played in his first US Amateur at Baltustrol in 1946) and Alice (she has won many more events than Pete) were both excellent players, they have always had an eye for challenging the best.

Still amateur golfers enjoy pitting their skills against courses of such notoriety. Ever since Harbour Town opened in 1971, golfers have routinely paid high green fees to challenge themselves against the latest Dye creation. They know that they are going to see something unique with features that tax their game like few other courses. Such is the case at French Lick. In 2007 Mr. Bill Cook hired Pete and Alice Dye to build a second course for the French Lick Resort as an attraction for the two hotels and their 686 rooms. You must lodge at either the French Lick Springs Hotel or the West Baden Springs Hotel in order to play the Dye Course.

Interestingly enough, Dye’s initial visit and tour around Mount Airie was disheartening. Despite a Bendelow course existing on a portion of the property, the remainder of the 312 acres sloped away too steeply from the peak where Thomas Taggert’s mansion sits. Pondering the problem overnight, Dye returned to the property the next day and left with a basic routing sketched on a napkin. By building up the perimeter of the property, Dye effectively created several ‘fingers ‘ of land to house holes 2/3, 4/5, 6/7, and 12/13. In this way he negated the severity of the property while creating ample fields for golf. One result is that the course is surprisingly walker friendly. In fact, Director of Golf Dave Harner can’t recall seeing the eighty-three year old Dye play the course in a cart; he always walks, bag slung over his shoulder.

According to Tim Liddy who first started working with Dye in 1990, ‘Dye worked hard to minimize the elevation change for the walking golfer. Although the topography has over 200 feet of elevation change the walk over deep ravines and up hills is very small. There are many occasions where a walk path was filled 30+ feet over a deep ravine to ease the walk from the tee to the fairway. Also, the walk from tee to green is very short, especially to the white tees from where a majority of golfers will likely play the course. Big hitters have a farther walk back and away from the green. Coore’s and Doak’s golf courses also exhibit this lesson in their design.’

From Dye’s perspective, he was thrilled not to be working on swampland and to have some elevation change at his disposal. Additionally, housing was not an issue because there wouldn’t be any. According to Dye, “I have spent the past five decades designing golf courses all over the world, including courses on great coastal sites. This new course at French Lick Resort has brought great excitement to Alice and me because the course is on arguably the best inland site I have ever worked on.’ Surely that is an exaggeration by the architect as otherwise he wouldn’t have felt compelled to move 2,500,000 cubic yards of dirt on what was a severe site. Yet, his underlying point is valid in that this course provides a sense of exhilaration that most inland courses simply can’t match.

Throughout his career, Dye has done much to defend par that grabs attention including wooden bulkheads and water hazards at the edge of fairways and greens. Just as effective though far less dramatic has been his construction of moderate size greens. Be it here or The Medalist (before Norman ruined it), Dye’s intermediate size greens in the 4,500 square foot range quickly identify the golfer who properly places his ball in the fairway and hits crisp iron approach shots. Though the long views will be what people remember about the Pete Dye Course, the green complexes are especially admirable. One influence originates from Dye’s days at Fort Bragg in the mid-1940s and time spent with Donald Ross at nearby Pinehurst No.2. He has long admired Ross’s pushed up greens and the hollows and depressions surrounding them and that source of inspiration is evident here.

Typical of what is to come, the first green measures 3,949 square feet and is surrounded by plenty of short grass.

Dye notes that green speeds were in the 5 to 6 Stimp range in 1916 when Donald Ross built the sister course in the valley below (click here to read its course profile). Hence, Ross was able to build several greens with over four feet of drop and the famous eighth green which at one point had a nine foot back to front drop. Compared to the Ross Course, the Dye greens made with the new A1/A4 blend are flatter but faster. Dye contends though that his greens feature more double breaks and that it may actually be harder to get the ball into the hole than on a typical back to front sloping green where the golfer can more readily gauge the break.

Though Dye has taken plenty of design chances over the years, his courses have stood the test of time. In the current World Top 100 by GOLF Magazine, six Dye courses are featured which is more than Tom Fazio, Jack Nicklaus, and the entire Trent Jones family combined. Indeed, the only living architects with a prayer of matching or surpassing him are two former pupils, Tom Doak who has five courses and Bill Coore who has four. Indeed, Dye has more courses (e.g. Oak Tree, Long Cove, The Honors Course and PGA West Stadium) that have fallen out of the World Top 100 than most architects could ever hope to have reach it.

French Lick will stand the test of time too. Thanks to the generosity of its founder Mr. Bill Cook, the course and the resort are debt free. Thomas Taggert’s mansion serves as the clubhouse (click here for more on its history) and no additional structures will be built on or around the course. Surrounded by state protected Hoosier National Forest, nothing will ever mar the thirty plus mile views. Also, Dye has already built an attention grabbing set of tees that make the course measure 8,100 yards! Surely, it will be decades before the specter of additional length becomes a reality.

Two yardages are given in the Holes to Note section below, first from the back at 8,100 yards and the other from the more manageable 6,700 set. Yes, it is startling to see a 300 plus yard par three that is played over dead flat land but at 8,100 yards, the Pete Dye Course represents a mere twenty-five yard increase in length per annum over Crooked Sticked’s length in 1966. Think about that! Save for plus handicap golfers, 90% plus of the golfers will play – and enjoy – the course from either the 6,700 or 6,100 yard set of tees.

Holes to Note

Second hole, 520/420 yards; One reason to play a Dye course is the expectation of seeing something new. Certainly that was true of Harbour Town, TPC Sawgrass and Whistling Straits when they debuted. Standing on the second tee, the golfer sees volcano bunkers (bunkers placed up high on mounds) and thinks this may be just such a feature. Surprise, Walter Travis beat Dye to the punch and he did so in 1919 at Hollywood Golf Club in Deal, New Jersey. What Hollywood doesn’t have, as do very few inland courses, are the amazing ten, twenty, thirty mile backdrops that are such a dominant feature here. According to Dye, ‘As I built the golf course I tried to get the tees, the fairways, and the greens in position that they have these long views over the valleys and hills. A lot of southern Indiana is natural forest, a lot of it is state owned, so you can see for miles. The ambiance of the course is the look, the vistas from all the different tees, greens, and fairways.’ Based on the view afforded by the approach to the second green and on many other subsequent shots throughout the round, he succeeded handsomely.

Eight volcano bunkers dot the grounds right of the second fairway. One design advantage:They hide the cart path.

Only the bravest – or most foolish?! – chase after this back hole located on a tiny 900 square foot plateau.

Fourth hole, 250/190 yards; Many of Dye’s most famous par threes feature water hazards such as the seventeenth at The Ocean Course at Kiawah, the iconic seventeenth at TPC Sawgrass, and the coastal one shotters on his Teeth of the Dog Course at Casa de Campo. However, the black and white nature of water takes away the art of recovery. Many students of Dye consider his best holes (par threes and otherwise) to be those those sans water such as the sixteenth at The Golf Club, the fourteenth at The Ocean Course, and the fourteenth at The Honors. Indeed, the favorite Dye course for the connoisseur remains his 1965 design at The Golf Club which incorporates water sparingly. Likewise, one of the pleasures of the Dye Course at French Lick is the paucity of water save for the sixteenth.

Dye benched the green of the highly attractive par three fourth into the hillside at the north end of the property.

Fifth hole, 390/345 yards; During the PGA of America’s Professional National Championship held here in 2010, this sub 400 yard hole played the most over par. How can that be?! With a multitude of 500 yard plus par fours and a 300 yard par three, the second shortest par four on the course played the hardest against par. Perhaps its modest length prompted less prudent tactics from the players, either in not hitting a short enough club from the tee to guarantee finding the fairway or from chasing after back hole locations where the green narrows to just a dozen paces. Regardless, be warned that this is not a hole on which to drop your guard.

Play smart. A club off the tee that stays just short of the left fairway bunker leaves only a 140 yard approach shot.

Like so many greens at Pinehurst No.2, this green is off-set to the fairway and is wider in the front than in the back.

Sixth hole, 515/395 yards; After paying someone $28,000,000 to build a course as Mr. Cook did here, the last thing that an owner wants is for the course to become irrelevant in a short period of time. Building a set of back markers at 8,100 yards ensures such will not be the case. Yet, so what? Those of us with swing speeds under 100 mph (and a waist line unlikely to enable improvement), don’t really care about the tee markers well behind us. More importantly, are we having fun from the forward set? Just look at the disparity between this hole’s yardage as played from the 8,100 yard set and the 6,700 yard set and you gain an appreciation of why this course can endure for decades as intended by the architect. Ahead at the green, Liddy points out another important design feature. Typical of this set of greens, ‘The green contours assist the approach shot at the front of the green, helping the average golfer, while the back pins are guarded by green contours, forcing the elite golfer to challenge a smaller area. This emphasis on using green contours effectively has influenced many later generations of architects.’

What a wise decision to clear the trees beyond this green site! The most panoramic view on the front results with Hoosier National Forest stretching for tens of miles in the distance. Even more so than with large bodies of water, these views – and the mood of the course – change dramatically from season to season. The early morning October photographs found throughout this profile more than suggest that the fall is a wonderful time to be here.

Key to the design success of this hole playing well from all its tees is that the front of the green was left open.

Eighth hole, 215/170 yards; Many of Dye’s star pupils including Bill Coore, Tom Doak, Tim Liddy, and Rod Whitman have gone on to build courses that reflect the land upon which they were given. Certainly, the same is true here in the context that the course was built on top of Mount Airie, epitomized by the number of impressive views. Yet, more so than his most famous pupils might deem necessary, Dye continues late in his career to move and shape vast amounts of terrain. One benefit is that he generally gets the shot requirements to balance out nicely within each nine, as well as for the course overall. For instance, this hole with its fall away to the right is the perfect foil to the other par three on this side that features a precipitous drop-off to the left.

The fact that the eighth incorporates Taggert’s mansion as its backdrop is no accident. Dye routed the vast majority of the holes so that a hook (i.e. the typical miss by a good golfer) would be more harshly punished than a slice. This one shotter is a rarity for the course in that the sharp fall off is on the right.

Ninth hole, 530/410 yards; At his most expansive designs, crescent shaped fairways are a favorite ploy of Dye. Give the golfer a view of the distant flag but swing the fairway well to one side of the line of charm. Aligning yourself properly on the tee is never easy on such holes as your vision – and then perhaps your shoulders – are unconsciously drawn to the sight of the flag. Dye loves unsettling the golfer and believes that doing so is one of his primary responsibilities as an architect. Without creating indecision and without making the golfer start to think, Dye fears he has failed.

Dye swung the ninth fairway left off the tee so that …

… he could later bend the hole right, thus creating the wonderful backdrop seen above for one’s approach shot.

Tenth hole, 390/350 yards; During the second half of the last century, returning nines to the clubhouse was commonplace. This contraint often hamstrung Dye and resulted in some indifferent tenth holes (e.g. The Golf Club, Casa de Campo). His penchant to move more earth later in his design career allowed him to force his will onto the property and create (rather than find) some very good tenth holes (e.g. Kiawah, Whistling Straits). The one common denominator? He built medium length par fours the vast majority of the time. This is no exception. Who wouldn’t agree that such holes help enable a smooth start on the second nine?

The preferred approach angle is afforded the golfer who drives near this bunker located on the left edge of the fairway some 100 yards from the 4,300 square foot green.

Eleventh hole, 455/395 yards; Some architects comfort the golfer by placing everything in plain view believing that it makes their courses more strategic because the player can readily understand how to tackle the hole. Ultimately, such design tactics rob these courses of any mystery. The player often becomes bored after just two or three rounds as he discovers all that is required to play the course well. Since his 1963 trip to Scotland, Dye has espoused an alternate perspective, one in which the occasional blind drive or blind approach is something to be desired. Dye appreciates that these creations help keep the element of chance in the game and serve to confuse the golfer and get him out of his comfort zone. In this case, the fairway is blind from most of the tees – and well right of where you might expect it to be.

This view is a fooler. It is taken from a rarely used tee position high on a hill whereby the eleventh becomes a drivable 330 par four. What a wonderful tee to use should they ever host an event like the Shell’s Wonderful World of Golf. The regular tees are lower, back and to the left. This view also highlights another design concept favored by Dye, which is a switchback hole. Here, a draw from the tee fits nicely into the curving fairway followed by the need to play a fade approach shot.

Twelfth hole, 530/390 yards; The favorite hole of many, the twelfth also possesses the fewest bunkers of any hole with ‘just’ four. Still it captures the spirit of the design and demonstrates the pains that Dye took to angle his holes to maximize the long views. Dye contends that the ambience of any course is what defines it, be it the coast at Pebble Beach or the rustic qualities of the foothills of the Tennessee mountains at The Honors Course. Unlike so many courses where homes or other man-made features stunt the views, this course will maintain an uncommon majesty until the end of time because of its forty mile views. Interestingly, this is the section of the course where the Bendelow holes existed. The difference? Dye’s hole is forty feet on top of Bendelow’s! One can only imagine what the Johnny Appleseed of Golf would have thought about man’s ability to move so much dirt.

What’s not to love?! Dye’s early opinions were shaped by some of the courses where he competed in the midwest including Seth Raynor’s Camargo outside of Cincinnati, Ohio. The influence of Raynor’s hard lines and engineered look is evident in Dye’s work above.

Played to one of the larger targets on the course, the approach to the twelfth with its wrap around bunker and clean horizon would make Raynor proud. Though the twelfth occupies one of the lowest parts of the property, it still affords one of the best views of the Indiana countryside.

Thirteenth hole, 210/160 yards; Dye famously became a fan of Raynor and his work after playing Camargo in the 1950s. Other particular favorite Raynor designs of Pete & Alice include Fisher’s Island and Yeamans Hall. Many point to Raynor’s steep and deep bunker style and angled greens as a major influence. One of Raynor’s template holes was the Redan and it too is a favorite of Dye’s. Two of his best interpretations are found here and at Kiawah.

The thirteenth green is the second biggest green on the course at nearly 9,400 square feet. Not so large for a Redan, Dye needed that much room to to build the kick slope and make the green function properly. Today’s hole location just beyond the kick slope is especially difficult. The green’s high front right to lower back left slope invariably sends many balls well past.

Fourteenth hole, 575/505 yards; As a set, the par fives offer the most options. Among them, this one plays the best. All golfers hit to the same fairway from their respective tee but then each is faced with a proverbial fork in the road. Does he play safely and bumble one down the right or take on the added challenge of finding the higher fairway to the left? The reward is ample for going high left as it provides the only view of the putting surface.

From all of the five tees golfers play to the portion of the fairway seen in the middle right above. From there, …

… the choice of where to go becomes less obvious.

Go right and lay up too close to the green and you have done yourself no favor. The approach shot is blind without even the tip of the flag in view.

A view from behind the green illustrates the advantage gained by playing your second shot onto the higher, left fairway.

Fifteenth hole, 385/345 yards; Bill Coore joined Pete Dye & Associates in 1972 where he learned the importance of working in the field and being hands on. Coore stated his own firm in 1982 before partnering with Ben Crenshaw in 1988. Ever since, Coore has preached the need to have a quiet moment or two in each round. Otherwise, he contends that the golfer eventually becomes numb if the architect throws one heroic shot after another at him. One such quiet moment occurs here and the hole and the course are the better for it.

Though not as visually arresting, the fifteenth nonetheless possesses fine golf qualities. Remember that the course is 900 feet above sea level and totally exposed. Finding this 3,750 square foot green is no mean task in any wind blowing in from the Kansas prairies.

Sixteenth hole, 300/185 yards; A real kick in the teeth from the back markers, this hole summarizes Dye’s dim view on the direction of technology. For the good player capable of creating 115 mph swing speeds, a driver might not even be required. Nonetheless, how depressing to see a 300 yard plus par three that is level from tee to green. For the golfers down below on the Ross Course who think they have their hands full with a trio of par threes in the 240 to 252 yard range, wait til they see this monster! Of course, it’s important not to overstate things based on one set of tees from which less than 5% of guests will ever play. From the forward tees, this turns into a more conventional mid-iron hole of the sort that the player has seen at a host of other Dye courses including The River Course at Blackwolf Run and Bulle Rock.

The key features that allow the sixteenth to play well are lots of teeing areas, plenty of fairway and a green that is open in front. Still, the perceived need to construct a 300 yard par three should cause trepidation in Far Hills, New Jersey.

Eighteenth hole, 655/590 yards; How can such a course end memorably? That very question puzzled Dye but after a few iterations, he came up with this swinging fairway that wraps around a ravine and feeds onto the course’s largest green at 9,610 square feet. Dye intends that you play from the set of tees that allows you to have a go at the green in two as the downhill approach shot is certainly one of the most heroic on the course. As with many of his best works (e.g. The Golf Club, Kiawah), Dye is pleased that the last three holes on each nine are different pars as it guarantees variety.

A drive pushed into this rendition of the Church Pew bunkers makes for a poor start to the eighteenth.

A good drive leaves the player with a variety of options how to play his second. As a frame of reference, the bunker at the right edge of the photograph is 100 yards from the green.

One other design aspect deserves to be mentioned and that is the cart paths. Sadly, they are part of golf in America even on a walking friendly course like this one. Dye worked hard to minimize their presence by using gravel tractor ruts with grass strips between them as cart paths. This approach reduces their artificial look from the many elevated vantage points.

Another thing about the Pete Dye Course is, well, it is a Pete Dye course! Pete made over 150 trips to the course and Alice about 30 during construction, so thoroughly energized were they by the scope of this project in their home state. Later in their careers, they let their name be used at projects done by their sons P.B. and Perry. Though some of those courses have merit, they aren’t truly representative of Pete’s own work.

Dye’s career started in Indiana but he soon gained renown and became such a force in architecture that he was awarded many plum venues for golf including miles of coastline in the Dominican Republic and the sand dunes of Kiawah Island. He also produced some of his most famous work on disadvantaged properties that required major enginnering/construction like the swampland outside of Jacksonville, Florida and an abandoned air strip near Kohler, Wisconsin. The portfolio of nearly one hundred courses that bear his name is remarkable for the gamut it runs.

The Pete Dye Course at French Lick essentially bridges those two categories. On one hand, its location on Mount Airie is dramatic and provides long views that are unmatched at any course that Dye designed. On the other, it was a major engineering accomplishment requiring both imagination and massive earth-moving. Decades of true in the field work have cultivated his unique abilities to tackle such a project and yield another sparkling design in an unmatched modern career. His PGA Tour Lifetime Achievement Award and the Old Tom Morris Award (the highest award given by the Golf Course Superintendents Association of America) are more than well deserved.

The End