Engineers Country Club

NY, USA

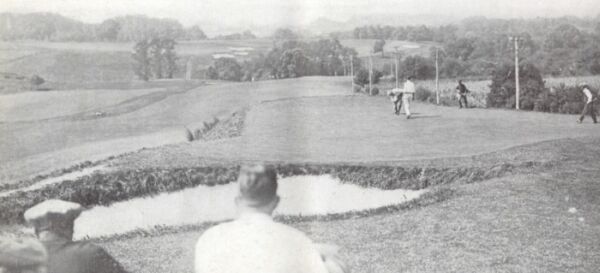

Herbert Strong built unique and memorable golf holes as well as any architect. Pictured is the famous 2 or 20 one shotter with steep drop offs left, right and behind.

How should golf course architects be judged? By how many great courses they build? Or perhaps by how many courses they build (the theory being more courses equals a greater opportunity for more people to enjoy the game)? How many unique and distinctive holes they create? How they further their profession? All the above can be a consideration but the picture clouds when the architect’s work doesn’t stand the test of time.

Certainly for an architect to be considered great, he must build great courses. And by definition, a course can’t be great without possessing great golf holes. Yet, what if the architect built both great holes and great courses only to have their character-filled work undone with time?

Such is the case with Herbert Strong, whose work was once widely regarded as among the best in the United States. Five courses were standouts, namely Ponte Verda Club in Florida, Manoir Richelieu in Canada, Inwood which hosted a PGA Championship and U.S. Open in the early 1920s, Canterbury Golf Club in Cleveland, Ohio and here.

Yet, despite the once impressive resume and being considered among the best architects in the country, Strong’s finest courses all suffered with the passage of time. Consequently, in any discussion of the great architects, Herbert Strong is rarely mentioned.What a great pity because if more appreciated his work, perhaps more of his designs would be restored.

Born in Ramsgate, England in 1879, Herbert Strong started his career in golf as a club maker. The course six kilometres down the road in Sandwich which Laidlaw Purveslaid out in 1887 surely had a huge influence on the young Strong. Purves’ course was even more wild and rugged than the Royal St. George’s course of today and featured plenty of blind shots. Set across massive sand hills, it provided a stern test of ball striking. Its quality was undeniable and it quickly hosted the Amateur Championship in 1892 and became the first English club to host the Open when it did so 1894. It hosted The Open again in 1899 which Harry Vardon won and in 1904.

Strong left for the United States in 1905 and in that same year, Harry Vardon wrote in The Complete Golfer the reasons why ‘I consider the links at Royal St. George’s Club to be the best that are to be found anywhere.’ In his article,Vardon talked about the need for constant good hitting or penalities, sometimes grave, would ensue. He admired how the bunkers were placed to challenge the good shots (as opposed to just trap the foozler). He admired the character found in the greens at St. George’s and how well guarded they were.

With Royal St. George’s firmly in mind, Strong arrived in New York and became the professional at Apawamis Club, a course that featured pronounced land forms and blind shots as well. In 1911, he moved to Inwood Country Club on Long Island and it is here where he got into golf course architecture. His remodelling of Inwood over the next several years wasof such quality that itwas rewarded witha PGA Championship and U.S. Open in the early 1920s.

Strong received the commission to build Engineers in 1918 in Roslyn and it received immediate praise from all quarters to the point where the PGA Championship was contested here in 1919, just one year after the course opened.

The attributes of Engineers were numerous. Firstly, the rolling topography must have thrilled Strong. Similar to Purves’ work at Royal St. George’s, Strong’s routing attacked the hills in every manner conceivable. Take for instance how he dealt with a hill in the middle of the property: his 3rd hole (half of today’s 4th) plays straight up it, his 4th hole (today’s 5th) rides atop the hill before tumbling down to the green below, his 5th hole is played across the hill’s left to right sloping base, and his 6th plays from another hill top back to the this same dominate hill.

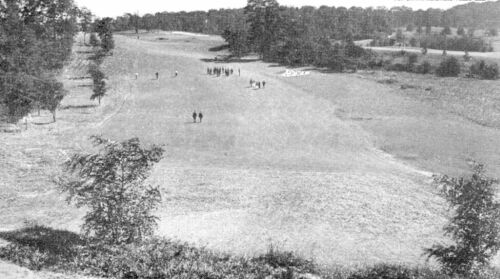

Strong’s third hole took the golfer up the hill with his 4th playing back down it at the top right.

Strong must have seen great potential in the open, rolling landscape when he first saw it. Pictured is a view from today’s 5th tee (Strong’s 4th) of the fairway before it tumblesover the hillcrest to a green below.

Tom MacWood’s research has uncovered this quote from Wilfred H. Follett, the Editor of Golf Illustrated and future partner of Devereux Emmet. Follett wrote on the eve of the 1919 PGA,

‘As regards the course of the Engineers’ Club, it is doubtful if any more testing links could have been chosen. It is true the course is a very young one, in fact, it was only opened last year, but even so, the fairways were in astonishing good condition….The course itself is a masterpiece and is the work of those two master craftsmen, Nature and Herbert Strong. Inaccuracy spells instant disaster. To drop the simile, anyone who has played the course a few times realizes that a shot ever so slightly off line, but still on the fairway, is instantly confronted with a seemingly easy second which in reality is almost impossible of perfect execution. The contour of the greens demands that the second shot be played from one angle only if perfect results are to be attained. There may or may not be a trap waiting for the shot which is played from the wrong angle, but there is always an awkward roll or slope which is certain to bring the ball up far from the flag. This is irritating, of course, to the nervous player, but he might bear in mind that if he was playing Garden City, where the traps outnumber those at Roslyn ten to one, all these shots played from the wrong angle would inevitably and promptly drop into a waiting trap, without ever giving the semblance of hope which he can, foolishly perhaps, enjoy at Engineers.’

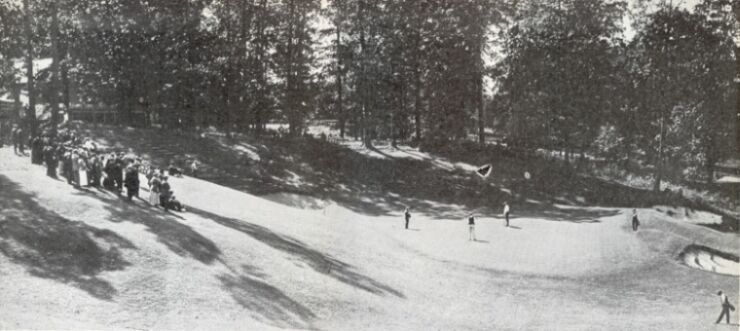

The day before the PGA they played a fourball event, the low score was a 76 (+6) by Jim Barnes, who was the eventual champion.

The course was 6362 par-70 with only one hole over 500 yards, making it relatively short in comparison to the U.S. Open venue of that season Inverness (6,600 yards) and Amateur site of the prior year Oakmont (6,700). Though Strong himself was very long off the tee, it is ironic that he conceived a course of this length. Still, the course was full of challenge and character and on the eve of the 1920 U.S. Amateur, no amateur had ever broken 75 at Engineers.

As for specific man-made design elements, Strong, like William Langford (another unsung architect of excellence), built a wide variety of bunkers and boldly contoured greens. Some of his bunkers at Engineers were so steep and deep (and cramped!) as to almost defy recovery while others like the one between today’s 9th and 12th greens are a large expanse of sand. The greens featured both pitch and imaginatively bold interior contours.

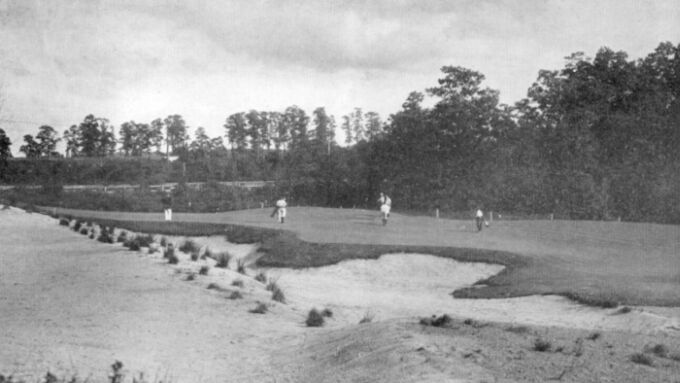

Strong’s 16th green is one of the wildest greens and best defended green complexes ever built. If replicated today, the green would have to be maintained at no more than a ‘7’ on the stimpmeter if the club wanted to use the more interesting right hole locations.

Note the huge expanse of sand in the middle bottom of the photograph between Strong’s 11th green on the left and Strong’s 8th green on the right. Did any other single architect manufacture sucha sprawling bunker pre-1920? Perhaps not.

And seen at ground level, Strong’s 11th green complex – imaginative bunkering and bold green contours forever characterized his design work.

At Engineers, Strong fulfilled every architect’s desideratum of building eighteen consecutive holes of genuine merit and in two specific cases at the 14th and 16th, two holes worthy of any list of the finest holes ever built.

Holes to Note

First hole, 380 yards; Engineers features a fascinating mix of green complexes ranging from the 2nd, 14th (a), and 16th where only aerial approaches will do to some like here, the 5th, and 15th which are open in front and invite the run up shot. In this case, the green follows the flow of the land which means it slopes from front to back. In addition, there is a small punchbowl in the right center side of the green, presenting all kinds of superb hole locations.

Skirting past the green’s gathering punchbowl on its right side to get to the back hole locations requires an approach of great skill – an altogether unique and wonderful green that functions very well!

Second hole, 405 yards; Strong built tough and challenging courses and it is no surprise that his best courses like Engineers, Inwood and Canterbury hosted so many important events. Take the 2nd for instance where Strong benched the green into a hillside at a height whereby a running shot had little chance, even when its bank is maintained at fairway height. Given the wood shafts of the day and given the fairway’s left to right slope and the uphill nature of the hole, the 2nd was tough just to reach in regulation. However, Strong capped it off with one of the most severely pitched greens ever devised.

The 2nd green drops five feet from high back left to lower front right, creating treacherous hole locations. Note the large landform in the hitting area with which the player must contend.

A view back down the 2nd from the elevated green – the left to right sloping fairway is evident in this view as well.

Fifth hole, 460 yards; Engineers measured under 6,400 yards when it hosted the 1919 PGA Championship and yet the winning score was high. Engineers only had one three shot hole at the time with Strong instead building several lengthy half par two shotters like here and the 14th.

The downhill approach to the 5th green. The bunker in front of the green is a good 20 yards shy from the green’s front edge.

Seventh hole, 290 yards; A rare example of a hole that technology has improved. In Strong’s day, the golfer was most likely to lay up to the base of the hill and wedge on with the bowl shaped green collecting the ball toward the green’s middle front. Today, the tiger golfer is almost compelled to give the green a go from the tee, which is when things get interesting as a recovery from either side of the green is infinitely more difficult than from directly in front of it.

Herbert Strong built unique and memorable golf holes as frequently as any architect.

Strong’s original 7th green bunkering is seen in the left center of this aerial. A well thought out tree removal program undertaken in the past few years is opening back up the course, something that would please Strong very much.

A side view of the 7th green, where an up and down is unlikely.

Eighth hole, 355 yards; Holes like the 14th, 16th and 18th have long been long famous in American golf but Strong built a strong supporting cast of holes too. As one ticks through the holes at Engineers, there is not an indifferent one to be found. Here at the 8th, the Club appreciates what they have and the grass is keep short on the green’s back high side and golfers can bank the ball onto this modified Redan green.

The 8th is a most attractive green complex with its high right to lower left Redan characteristics.

Ninth hole, 175 yards; One thinks of the one shot holes at Rye Golf Club (70 kilometres from Strong’s home in England) when playing this hole as it is a potential card wrecker. The hole is essentially flat as the tee and green are both along a plateau but there is a twenty foot drop to the immediate right of the green complex. Strong sloped the green from left to right and thus, those who (naturally) shy away from the obvious trouble on the right will find themselves with a problematic recovery shot. Those who play confidently down the center line of the hole may be rewarded with an uphill birdie putt.

Fourteenth hole, 450yards; The 14th bends left along the edge of a steep drop off and the golfer would dearly like to hug the left in order to shorten his approach. A simple yet strategic hole, thanks to Strong’s excellent routing. In Strong’s day, the trees left weren’t as dominate and the golfer had a clearer view of the steep drop left of today’s fairway.

Fourteenth hole (a),95 yards; Other famous short one shotters like the 7th at Pebble Beach and the 8th at Royal Troon rely on the wind to further their challenge. Not so with this little brute – the green complex is so heavily fortified and the putting surface so long and thin that the hole preys on the golfer’s mind long before he reaches it.While the severe penalty for failure may be out of proportion for those who (mistakenly) insist that golf be fair, this is a stand-alone unique hole in the history of golf course architecture. Perhaps the fact that golf was more of a match play game back in Strong’s day emboldened Strong to build such an all or nothing hole – whatever the reason, it is a shame more short, waterless holes aren’t built like it. In The American Golfer in 1923 J.S. Worthington wrote a series of articles entitled “The Best Golf Holes I Have Played.” Worthington was a world traveler who visited all the great courses in America and the United Kingdom and he started his discussion on great par-3’s with the 14th at Engineers: “More malediction, praise and lamentation has been bestowed upon this particular creation than any other short hole in existence.”

The all-world 2 or 20 hole.

Sixteenth hole, 365 yards; Some green complexes appear both ruggedly defended and stunningly beautiful at the same time. Famous examples include the 2nd at Pine Valley Golf Club, the 7th at Royal Melbourne West, the the 5th at Royal County Down, and the 10th at Friar’s Head. Where the natural defenses are so interesting, the hole in turn becomes equally arresting. Such is the case with the 16th at Engineers where the green complex is on the far side of an embankment. Strong leveled off the hillside (some would say not enough!) to create a large, wildly pitched green that falls sharply from back left to front right. The sight of this well fortified green complex as one comes over the crest of the hill stays with the golfer for a long time.

The current 16th putting surface is presently maintained at approximately half the size…

…of Strong’s original design.

This view back back up the 16th hole highlights some of the rugged attributes of the property.

Eighteenth hole, 420 yards; Following the example established by The Old Course at St. Andrews, many architects see fit for the 1st and 18th holes to parallel one another heading in opposite directions. In some cases such as Shoreacres, the ground near the clubhouse isn’t inspiring and the architect uses the two holes to get the golfer out and then back in from the better golfing terrain. However, there is no such let-down with the 18th at the Engineers.

The approach to the Home hole plays through a valley to a green well below.

The 18th green as seen eighty years ago was more heavily bunkered.

Again, Tom MacWood’s research has found this gem of a quote from Grantland Rice prior to Engineers hosting the U.S. Amateur in 1920:

‘With the rugged texture of its bordering trouble–with its baffling, sloping greens and the penalties that await mistakes, the Engineers Course near Roslyn, Long Island, will be a test that no entrant in the impending championship will ever regard as a light one…Scenic beauty and natural ruggedness are two of the outstanding features of this battlefield of golf where the finest are gathering for the next big title. Many of the leaders have tried to take it by direct assault the past two years but only a pitiful few have succeeded in returning a score with four or six strokes of par. And the ghosts of dead hopes and wrecked dreams wander in multitudes up and down the ravines and valleys and drift across the hills. While all the hazards are not so annihilating there are many spots of trouble where one might as Dante read before the gates of Infreno–All hope abandoned, ye who enter here. No young course in the history of golf, let it go back four hundred years, has come in for as much discussion and comment or has at such an early period been awarded two big championships as the golfing rendezvous of the Engineers upon Long Island’s north shore. There are those who think it the finest course in the country. There are others who look upon it as a bag of tricks and who finish a round muttering strange things. In any event it is something different in golf and since variety remains the spice of life with no able substitute, the fact that the course has attracted so much interest is not be overlooked.’

Strong’s feature rich design with its variety of hazards and bold greens was once considered ‘…the finest course in the country’ according to the astute Grantland Rice. However, these same features which made the course good enough to host a PGA Championship in its second year were also viewed by some as too quirky. Devereux Emmet was hired by the Club to consult and advise on changes after the 1920 U.S. Amateur, despite Strong still living in the area. In part, he softened the contoursof several of the greens.

And during the next 80 years, at least five other architects have altered Strong’s design as well. Still, the course of today generally plays the way that it did in Strong’s day: the set of eighteen targets more than make up for any lack of length.

Still, given the praise that reigned down on Engineers throughout the 1920s and 1930s, one can only wish that club boards at Engineers will appreciate what they once had. As the black and white photographs found by reseacher Tom MacWood for this course profile show, plenty of photographic evidence exists to act as a blueprint for fairway expansion/mowing patterns, bunker scheme and green recapturing, and additional tree removal efforts. The property and routing are still in tact and fully restored, Engineers becomes one of the must-see original designs in the world of golf – short in length but long in design character like so many of the great inland United Kingdom courses such as West Sussex and Swinley Forest.

And perhaps the great Herbert Strong would then eventually begin to get his due as well.

The stately clubhouse has seen many of golf’s greats like Gene Sarazen and Bob Jones come through its doors.

The author thanks Tom MacWood for his help and research for this course profile and for sourcing the black and white photographs.

The End

![The Park, West Palm (Lit 9) [2023]](https://golfclubatlas.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_7092-2-scaled-500x383.jpg)