Arts and Crafts Golf Part I

by Thomas MacWood

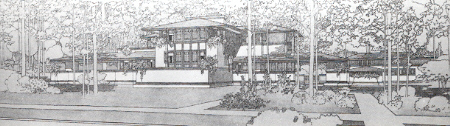

Alister MacKenzie’s 16th at Pasatiempo

The Golden Age of golf-architecture, it is difficult to have a discussion with a serious student of golf design without it entering the conversation. The accomplished golf-architect Tom Simpson and his co-author Art historian Newton Wethered are said to have invented the term in their book The Architectural Side of Golf (1929). While it is true Wethered and Simpson did use the term ‘Golden Age’, they used it to describe a period of golf, from the haskel ball to the time of the book’s publishing. They claimed it was a great age due to the advent of modern equipment, improved maintenance practices, bright clothing, and well-furnished clubhouses, but surprisingly they never used the term in a golf-architectural context. The great Bernard Darwin did not use the term, nor did Herbert Warren Wind — actually Wind did allude to a ‘Golden Age’ in 1966, but he used it to chastise the disappointing state of contemporary golf-architecutre, writing that regrettably we were not enjoying a ‘Golden Age’ despite so many apparent advantages. It appears the first time it was used to describe a period of golf-architecture was 1976, by Donald Steel in The World Atlas of Golf, followed by Cornish and Whitten’s The Golf Course in 1981, and then Doak, Shackelford, Klein and an army of succeeding writers.

Although nearly everyone agrees on the general concept of the ‘Golden Age’ and the many talented golf-architects involved, the exact time frame varies from writer to writer — between the wars (1919-1936), turn of the century to world depression (1900-1930), the twenties (1920-1929), and the National Golf Links to Prairie Dunes (1911-1937). Perhaps a merger of these dates would make the most sense, after all many of these men, including Donald Ross and Harry Colt, created excellent work before and after these narrower periods. And to emphasize the 20’s reflects a purely American perspective, the 1930’s were productive in Europe, Japan and Canada, and the high point of British economics/golf course development occured after the turn of the century but before WWI, and it is difficult, if not impossible, to separate British development from that in America, or the rest of world for that matter.

For the sake of argument if we accept this larger time frame, and we agree that this extraordinary period began at the turn of the century, the next logical question is why it began, what were the circumstances that led to its birth. A great deal has already been written of Willie Park-Jr. launching this remarkable era at the turn of the century with his dual heathland designs of Sunningdale and Huntercombe. Sir Guy Campbell wrote that Park had laid ‘the foundation stone of golf architecture’ and ‘set the standard by which the famous architects who followed . . . developed his methods and amplified his art.’ He went on to say that Huntercombe and Sunningdale were ‘two courses of quality and continuing charm that may be said mark the springboard of modern practice.’ And we know that Herbert Fowler and Harry Colt soon followed Park, and that these three rescued golf design from the’dark ages of golf architecture’ giving rise to the so called ‘Golden Age.’ This story has been told many times — the dark ages, the heathland breakthrough, and the subsequent ‘Golden Age’ with its icons of Ross, MacKenzie, Macdonald and a number of other greats. What has not been explored, however, are the reasons why this era began. What were the circumstances that led to this dramatic change in direction that elevated golf architecture from mundane task to high art? Why are these golf courses so appealing? And what about these men who created these courses, what were their influences, what did they have in common? And finally if we are able to discover the answer to these questions, can the lesson be applied to our modern art?

The Dark Ages

It is not known exactly when golf was first played in Scotland, the earliest references date from the mid 1300’s, although some speculate a form of the game may have been played as early as 1200. We normally think of golf as an ancient game, but its popularity is relatively recent. The common image of a sport which enjoyed universal popularity throughout Scotland is not entirely accurate, its popularity was limited to specific coastal pockets. In fact in 1850 there were only 17 golf clubs in Scotland, this is when the feathery was replaced by the more practical gutta percha. The cheaper more durable gutta allowed the game to expand throughout Scotland, and to move out beyond her borders and into England. The result was an increase in the number of golf courses from 17 to 43 — still fairly modest growth. However due to the economic explosion of the late Victorian Era, fueled by the Industrial Revolution, that growth accelerated and between 1880 to1900 there were 150 new clubs established. This is the period when the modern sport of golf began.

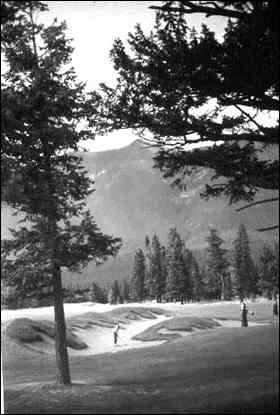

The rugged beauty of links golf.

Naturally with the game’s widespread popularity came a need to establish new golf courses and most importantly a new type of expert to lay them out. Those first golf course designers were the greenkeepers and professionals, men like Old Tom Morris, Willie Dunn and Tom Dunn. They were the native sons of the old natural golf links — St. Andrews, Musselburgh and Prestwick. But despite their familiarity with these ancient models their work was very disappointing. Tom Simpson wrote, ‘They failed to reproduce any of the features of the courses on which they were bread and born, or to realize the principles on which they had been made. Their imagination took them no further than the inception of flat gun-platform greens, invariably oblong, round or square, supported by railway embankment sides or batters . . . The bunkers that were constructed on the fairways may be described as rectangular ramparts of a peculiarly obnxious type, stretching at regular intervals across the course and having no architectural merit whatever.’

One of the reasons these men failed was due to the methods they utilized in laying out these golf courses, or the lack there of. The ancient links may have taken centuries to be formed, these men preferred a much shorter duration. There was very little time and even less forethought put into the design of a golf course. As Bernard Darwin’s described, ‘The laying out of courses used once to be a rather a rule-of-thumb business done by rather simple-minded and unimaginative people who did not go far beyond hills to drive over, hollows for putting greens and, generally speaking, holes formed on the model of a steeplechase course.’

Harry Colt recalled a particular incident, ‘A leading man on the subject was introduced for the first time to 150 acres of good golfing ground, and we all gathered around to see the golf course created instantly. It was something like following a water-deviner with his twig of hazel. Without a moments hesitation he fixed the first tee, and then, going away at full speed, he brought us up abruptly in a deep hollow, and a stake was set up to show the exact position of the first hole. Ground was selected for the second tee, and then we all started off again, and arrived in a panting state at a hollow deeper than the first, where another stake was set up for the second hole. Then away again at full speed for the third hole, and so on. Towards the end we had to tack backwards and fowards half a dozen times to get in the required number of holes. The thing was done in a few hours, lunch was eaten, and the train caught, but the course, thank heavens, was never constructed!’

Stories like that became common place as a result of the great demand to build courses near or within the large towns and cities, especially in urbanly concentrated England. In the early years the game was exclusively seaside, but the new generation of golfers were busy men unwilling or unable to waste precious time traveling. Unfortunately many of the inland sites were ill suited for the game, featuring heavy soil and poor drainage. The weaknesses of the sites were compounded by their odd Victorian design methods. C.H.Alison wrote, ‘The construction of these courses was simple in the extreme. There was only one form of bunker. This consisted of a rampart built of sods with a trench in front of it filled with a sticky substance, usually dark red in colour. The face of the rampart was perpendicular. It was precisely 3 ft. 6 ins. in height throughout, and ran at an exact right-angle to the line of play. The number of these obstacles varied according to the length . . . A stranger, therefore, was able to ascertain the bogey of hole by counting the number of bunkers, and adding two to his total . . . There were no side-hazards except long grass and trees. The fairways were invariably rectangular, and the putting-greens were square and flat . . . It will be realised that this stereotyped placing of bunkers rendered the game extremely monotonous . . . moreover, the rampart style bunker did not add to the beauty of the landscape, or lend an additional thrill to the stroke by its awe-inspiring appearance. Another notable feature . . . was the extreme flatness of the approaches. Any bold features which existed were used as hazards for the tee shot if they were used at all. Very seldom was a green placed in such a position as to render the approach play naturally interesting, while to create grass slopes or hollows artificially was an unknown art.’ New seaside construction also suffered, ‘some excellent courses already existed in 1890, but in constructing new course near the sea there was in the Victorian Era a tendency to take all hazards at a right-angle and to include a very large number of blind approaches.’

Cassiobury Park was a typical inland course.

Golf architect Alister MacKenzie added, ‘In the Victorian Era . . . almost all new golf courses were planned by professionals, and were, incidentally, amazingly bad. They were built with mathematical precision, a cop bunker extending from the rough on the one side, to the rough on the other, and similar cop bunker placed on the second shot. There was entire absence of strategy, interest and excitement except where some natural irremovable object intervened to prevent the designer from carrying out his nefarious plans.’

Of all the inland creators Tom Dunn seemed to be the busiest and most notorious. Horace Hutchinson described the scene, ‘He went about the country laying the courses out, and as he was a very courteous Nature’s gentleman, and always liked to say the pleasant thing, he gave praise to each course, as he contrived it, so liberally that some wag invented the conundrum. ‘Mention any inland course of which Tom Dunn has not said that it was the best of its kind ever seen.’ His idea—and really he had but one—was to throw up a barrier, with a ditch, called for euphony’s sake a ‘bunker,’ on the near side of it, right across the course, to be carried from the tee, another of same kind to be carried with the second shot, and similarly a third. It was a simple plan, nor is Tom Dunn to be censored because he could not evolve something more like a colourable imitation of the natural hazard. A man is not be criticized because he is not in advance of his time.’

While these new golf-course designers were successful in bringing the game to new districts and providing venues for legions of new golfers, they were utterly guilty of ignoring their native traditions — for these new golf courses were radically artificial and in direct contrast to the wonderful natural links. Instead of embracing the vernacular models of St. Andrews, North Berwick and Prestwick, these men turned their back on their traditions and on the natural. But as Hutchinson said, it was not entirely their fault, after all they were traveling unchartered territory, and when forced to cover new ground there is a tendency to fall back on current trends, and these odd designs were very much a reflection of popular aesthetic tastes.

Victorian Aesthetics

Nature designed the first golf courses. It has been repeated often, the first golfers developed the game over the barren linksland. The first golf courses were discovered not built and evolved slowly and naturally. So when the game’s popularity took off in the second half the 19th century and there became a demand for new courses in new locals, it no doubt presented a dilemma. The old links had not been’designed’ by man and there was very little precedent for the design process. Certainly there had been limited intervention by early golfers on these natural links, but now these golf professionals were asked to devise completely new golf courses. Although most of these men were ill educated, they were still products of a modern nation — a nation blessed with superior know-how, artistic sophistication and technological advantage — so when presented with the challenge of ‘design’, these first golf designers naturally turned to the cultural influences and contemporary aesthetic tastes for their creative model.

To fully understand contemporary Victorian tastes, you must look to the preceding period. Pre-Victorian Britain benefited from the defeat of France at Waterloo and an economic boom as a result of the early industrial revolution. The culture of this period was dominated by the aristocratic class. Britain was ruled by an opulent landed aristocracy, whose life style was highly enviable. This lifestyle was epitomized by the large country houses, supported by great estates and filled with collections of antiques, sculptures, books and fine pictures by old masters. The acknowledged measure of taste for the aristocracy, at least for those formally educated, was provided by the art and literature of ancient Greece and Rome (whose prestige had been amplified by the Renaissance), a result of an emphasis of Greek and Latin in the curricula of schools and universities all over Europe. Classicism was the pattern of taste to be found in all the major European states of the 18th century and dominated imperial Britain. The return to the principles of Classic art and architecture was a return to strictly defined aesthetic order, as well, evoking the glories of Ancient Rome. The result was architecture based on rules, order and clarity, where straight lines were favored over curves, of strict proportions and defined volumes, and above all brutal symmetry.

Ironically as architecture was emphasizing rigid structure and order, garden art was rejecting the formal for the natural. In the eighteenth century men like William Kent, Capability Brown and Humphry Repton began creating idealized visions of the natural landscape as opposed to the geometric formality of their predecessors. This phase was known as the Picturesque and it was inspired by the carefully contrived landscape paintings of the 17th century and a renewed interest in the medieval past. At the dawn of the Victorian era (1837 -1901) these two styles, the Picturesque and Classical, existed amicably side by side.

Entering the early Victorian era (1830 -1850) the Classical tradition in architecture continued to dominate, Classical being the natural choice for most public buildings throughout the period. During the High Victorian period (1850 -1870), although neoclassical buildings continued to be built, it was the Renaissance revival which was predominant. The new richness of this mode was largely French inspired and featured opulent decoration. This was also when a Gothic revival began to gather pace, sparked by the House of Parliament by Sir Charles Barry, the result of a design competition in which ‘Gothic’ or ‘Elizabethan’ styles was stipulated. But even the normally organic Gothic was presented by Barry in a Classical form in the general symmetrical arrangement of the building.

As the Picturesque garden style was becoming fashionable throughout Europe, ironically Victorian designers were rediscovering the geometric gardens of the Italian Renaissance. The naturally inspired garden had enjoyed its day, and from around 1830 the formal garden was back in favor. Not unlike the over stylized Victorian interiors, the gardens of this period were stuffed with ideas — geometric topiary, color, structures, themes and exotic plants. Even the conventional arts were not immune from this insistence on formality and strict order. The Royal Academy, which dominated all aspects of artistic thought, taught art students to compose paintings with pyramidal groupings of figures, one major source of light at one side matched by a lesser on the opposite, and an emphasis on rich tone at the expense of color.

Victorian symmetry and formality.

It was under this backdrop that the early golf designers began, but Victorian aesthetic tastes were not the lone factor effecting those first golf-architects. A number of other sports were gaining converts among the middle class — cricket and tennis in particular were enjoying similar popularity. Like golf these sports featured a weapon as well as a ball, and like golf these games were played on grass, however cricket and tennis were played over a level lawn of strict geometric dimensions. So when golf was brought inland to the urban centers, it seems reasonable to believe that many of the turf specialists involved in constructing these playing lawns, would have also been involved in some capacity with these early golf fields. And beyond these aesthetic influences, there were also cost factors, golf required a fairly large parcel of land which was comparatively expensive. These first designers were keenly aware of the finacial pressures of their sport, and believed quick, simple and cheaply constructed courses was the only way to proceed. Considering the entire cultural climate, it is not difficult to comprehend why the Victorian golf-architects produced such unnatural work.

Part II

The Reformers

From the aesthetics of Victorian England came three influential dissenters — Pugin, Ruskin and Morris — with Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin (1812 -1852) being the first. His father, A.C. Pugin, had come to England during the French Revolution and worked for the architect John Nash, drawing the fashionable Gothic details that his clients demanded and Nash detested. AWN Pugin, born in London in 1812, assisted his father as a boy with both his designs and in the production of several books on Gothic architecture. In fact the younger Pugin was thought to be even more knowledgeable than his father and at 15, was chosen to design the faux-Gothic furniture for Windsor Castle. (He later called these designs ‘enormities’ and remarked that ‘a man who remains any length of time in a modern Gothic room, and escapes without being wounded by some minutiae, may consider himself extremely fortunate’)

As a youth Pugin was intensely fond of the sea (He once said, ‘There is nothing worth living for but Christian architecture and a boat’) and ironically his life would be rocked by constant turbulence. He found himself shipwrecked off the Firth of Forth in 1830, got married in 1831, lost his wife a year later, got married again in 1833, lost his second wife in 1844, got married once more in 1848, and lost his mind in 1851. A short life that included three marriages, eight children and over a hundred designs (mostly churches) and great quantities of ornaments, furniture and vestments. He drew every line himself and when asked why he didn’t give the mechanical part of the work to a clerk, he replied, ‘Clerk, my dear sir, clerk, I never employ one: I should kill him in a week.’ Pugin died at the age of forty from overwork.

The turning point in Pugin’s life was his conversion to Catholicism in 1835. The following year he published a book entitled Contrasts (a slight reduction from its original title, A Parallel between the Noble Edifices of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries, and Similar Buildings of the Present Day; Shewing the Present Decay of Taste). In the book Pugin argued that Gothic was the only true Christian architecture. It was illustrated by brilliant comparisons between the ‘meanness, cruelty and vulgarity’ of buildings of his own day, the Classical and faux-Gothic, and the glories of the true Gothic of the pre-Reformation Catholic past. He claimed Gothic architecture was produced by the Catholic faith and that Classic architecture was Pagan. The Reformation had been a dreadful scourge, and medieval architecture was greatly superior to anything produced by the Renaissance or Classic revivals — ‘a bastard Greek, nondescript modern style has ravaged many of the most interesting cities of Europe.’

Pugin believed that beauty should grow from necessity, that there were two great rules for design, ‘1st, that there should be no features about a building, which are not necessary for convenience, construction or propriety; 2nd, that all ornament should consist of the essential construction of the building.’ These two principles would influence the succeeding Arts and Crafts Movement, and eventually led to freely composed asymmetrical buildings. ‘Architectural features are continually tacked on buildings which they have no connection, merely for the sake of what is termed effect; and ornaments are actually constructed, instead of forming the decoration of construction, to which in good taste they should always be subservient.’

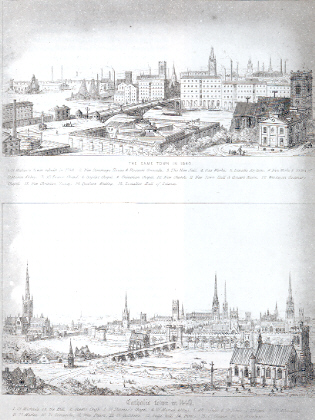

AWN Pugin, ‘Contrasts’, showing the same town in Victorian and middles ages.

Another of his doctrines was ‘fidelity to place’, and it too was adopted by the Arts and Crafts movement. It argued that environmental factors were responsible for a given areas architectural traditions and styles. To create a truly sympathetic design one must embrace those naturally evolved regional traditions along with the materials naturally found in the area. For example, Pugin’s design at St.Augustines reflected the regional Gothic tradition and was constructed of local Kentish brown stones excavated nearby. ‘What does an Italian house do in England?’, railing against the prevailing fashion for Italianate villas.’Is there a similarity between our climate and that of Italy? Not in the least . . . another objection to Italian architecture is this — we are not Italians, we are Englishmen.’

John Ruskin (1819 -1900) was the first professor of art history at Oxford University and the most influential art critic of his day. He shared Pugin’s disgust with the classical world, not because it was ‘pagan’ but because its aesthetic was based on symmetry and regulation. For Ruskin the opposite qualities — asymmetry, irregularity and roughness — made Gothic architecture superior. One of the sternest critics of industrialization and the only Arts and Crafts reformer to reject the use of machinery altogether, Ruskin believed the industrial revolution had turned designers into anonymous laborers. Only by returning to handwork would individuality be restored and along with it, quality.

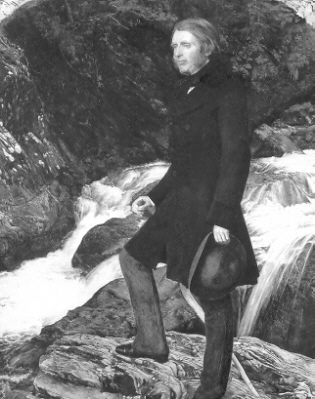

‘John Ruskin’ by JE Millais, Pre-Raphaelite artist.

The son of a wealthy and cultivated London sherry merchant, Ruskin’s upbringing was abnormally strict, however he was always encouraged to read, write, and draw, and to appreciate the beauties of nature. Following an education at Oxford, he became well-known as a critic of landscape painting and champion of the works of the painter Turner and the Pre-Raphaelites, a group of artists who were opposed to the stale formula-driven art produced by the Royal Academy. Ruskin promoted contemporary art and artists, which accelerated collection of these works by the new middle class. At the same time he was rejecting classicality, ‘All classicality . . . is utterly vain and absurd, if we are to do anything great, good, awful, religious, it must be got out of our own little island, and out of these very times, railroads and all.’ Like Pugin before him Ruskin argued that Gothic was the architecture of northern Europe and that unlike Classical architecture built by slaves, it was the product of free craftsmen. Classical’s aim was perfection of execution according to a series of clearly defined rules, ‘in the end any workman could produce it if he were beaten hard enough.’

Ruskin maintained that architecture should be true, with no hidden structures, no veneers or finishes and beauty in architecture was only possible if inspired by nature. Truly humane architecture must be imperfect — what he called savage, the Gothic ‘naturalism’. The Gothic craftsman, Ruskin believed, not only expressed his own imperfections in his art, but by studying nature, the imperfections of his subjects as well. Because Gothic was not tied to strict rules, it was ‘the only rational architecture,’ for it could fit itself to every use or circumstance. ‘It is one of the chief virtues of the Gothic builders, that they never suffered ideas of outside symmetries and consistencies to interfere with the real use and value of what they did . . . If they wanted a window, they opened one; a room, they added one; a buttress, they built one; utterly regardless of any established conventionalities of external appearance, knowing . . . that such daring interruptions of the formal plan would rather give additional interest to its symmetry than injure it.’

Ruskin’s two most famous books, The Seven Lamps of Architecture and The Stones of Venice, established criteria for judging art that were followed well into the twentieth century. The Seven Lamps of Architecture was a personal reaction against the rigidity of the classical style. Ruskin concerns himself with defining the ethical and spiritual, as well as the aesthetic nature of architecture.

The Lamp of Sacrifice – Architecture by definition is an art which rises above’building’ and requires additional effort and resources which are not necessary to strict utility

The Lamp of Truth – No disguised supports, no sham materials, no machine work for handwork

The Lamp of Power – Refers to the effect of architecture to consciously inspire awe

The Lamp of Beauty – Only possible through imitation of, or inspiration from nature

The Lamp of Life – Architecture must express a fullness of life; embrace boldness and irregularity, scorn refinement and also be the work of men as men

The Lamp of Memory – The greatest glory of a building is its age and we must therefore build for permanence

The Lamp of Obedience – Architecture should be conservative. Expression is good, but preoccupation with originality is essentially bad. Architects should not seek to consciously introduce new Style

In his later years Ruskin was devoted to social and political issues, advocating a form of state socialism. One of his last political efforts was the founding the St.George’s Guild, a society to pursue the ideals of the dignity of labor and fight against machines and its alienating effect. The experiment failed, while embracing what he called socialism, Ruskin always stressed ‘the impossibility of equality.’ In 1880 he began to suffer a progressive mental collapse, and was unable to testify during the Whistler trial when the artist sued Ruskin for libel. The last years of his life were a gradual descent into madness.

While Ruskin was one of the most widely read English authors, William Morris’ (1834-1896) influence was even more far reaching. He too was a prolific lecturer and writer whose works were popular on both sides of the Atlantic, but his stature as the versatile figure of the Arts and Crafts movement came from the example he set as a consummate craftsman.

Morris was born in Walthamstow, the son of a successful businessman. In 1840, when Morris was six, his father acquired a fortune speculating in Devon copper mine, and the family moved to Woodford Hall on the edge of Epping Forest. The Epping period — spent riding horses, fishing, hunting, gardening, bread baking, brewing beer, learning of plants and birds — formed Morris’s enduring appreciation of nature. When his father died in 1847, the family was forced to move back to Walthamstow. All his life, Morris tried to recreate the idyllic, almost medieval life at Woodford Hall.

Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris.

A love for medieval beauty was fostered during his undergraduate years at Oxford, little changed since the fifteenth century. Having gone there to study for the ministry, he read The Stones of Venice and decided to become an architect. After experimenting with both architecture and painting, Morris devoted himself to the decorative arts. In 1861 he formed what would become Morris and Company, a collaborative effort with a goal of uniting all the arts. The Pre-Raphaelite painters Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Edward Burne-Jones and Edward Madox Brown, and the architect Phillip Webb were also founding members. Their diverse talents combined to produce furniture, stained glass, wall-paintings, decorative tiles, embroidery, wallpaper, tapestry and metalwork. Morris was the embodiment of the Arts and Craft movement; blending art, ideals and business.

Morris’s design patterns for wall paper, textiles and tapestries (which remain popular to this day), were derived from the underlying geometry of flowers and plants, and was characterized by natural materials. As a Ruskin disciple, Morris understood the importance of craft work as well as design. ‘For . . . everything made by man’s hand has a form, which must be either beautiful or ugly; beautiful if it is in accord with nature, and helps her; ugly if it is discordant with nature, and thwarts her.’

Morris chair, Stickley’s Craftsman Workshops (1910).

Morris believed that if the new architecture and planning were to draw inspiration from the old, preservation of historic work was vitally important — not only as a model, but as reminder of the continuity of past, present and future. He formed the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB) in 1877. Morris had been outraged by a proposal by the architect Sir Gilbert Scott to restore Tewksbury Abbey.’My eyes just caught the word ‘restoration’ in the morning paper, and on looking closer, I saw that this time it is nothing less than the Minster of Tewksbury that is to be destroyed by Sir Gilbert Scott.’ So begins a letter which Morris sent to the newspaper Athenaeum as a protest against the wide spread practice of church restoration.

Earlier restorations by Victorian architects intended to modernize or return buildings to their original state had, in Morris’s view, ruined much fine medieval architecture, partly through ignorance and partly through the use of modern construction methods, under which it was impossible for carvers to express the true Gothic savageness. Morris also alleged that architects advised large-scale rebuilding to increase their commissions, which was later supported by a document that showed spending on church restoration had outstripped new construction for the previous twenty years. SPAB successfully popularized a doctrine of ‘honest’ repair rather than wholesale restoration to a state of perfection which often had reality not in history but the architects imagination. In the SPAB manifesto Morris urged, ‘to treat our ancient buildings as monuments of a bygone art, created by bygone manners, that modern art cannot meddle with without destroying, Thus, and thus only . . . Can we protect out ancient buildings and hand them down instructive and venerable to those that come after us.’ The obvious result of SPAB was preservation, but it also enabled Morris to extol the simplicity and beauty of vernacular buildings, which became the inspiration for the Arts and Crafts architects that followed.

In 1883 Morris became a member of the Democratic Federation, the only socialist body then in existence. It was the start of commitment to the socialist movement for which he remained faithful to the end of his life. A successful capitalist who preached communism; a designer of mass-produced art who believed in the freedom of individual craftsman; a beneficiary of machine-made ornament who preferred utter simplicity — the Morris paradox.

The Arts and Crafts Movement

The Arts and Crafts movement has long confounded historians. Although it is universally agreed to have started in Britain, there is little agreement as to exactly when it began — or exactly when it ended for that matter. Its evolution was a gradual process rather than a sudden revelation. To further complicate matters it was an artistic movement without a definitive style. The movement promoted individualism and the incorporation of regional traditions, resulting in startling diversity from an ‘Olde English’ cottage in Cotswold to an Adobe inspired home in Santa Fe. As A&C historian Eizabeth Cumming wrote, ‘Although practitioners had widely differing agendas, they shared the ideal of individual expression, of design that could draw inspiration from the past but would be no slavish imitation of historical models. Buildings were crafted of local materials and designed to fit into the landscape and reflect vernacular tradition.’

Ernest Gimson, Stoneywell Cottage, Leicester, Devon (1898)

And because it was not so much a style as an approach, the Arts and Crafts movement has been little more than a foot note historically. Its recognition can be traced to Modern architecture’s inability to find humanity and individualism, allowing the simplicity, informality and honesty of the Arts and Crafts movement to enjoy a resurgence. And with this renewed interest, architectural and social historians have begun to recognize ‘the immense scale and range of both professional and amateur Arts and Crafts activity and to unravel its complex and sometimes contradictory ideologies’.

CFA Voysey, Moorcrag, Lake Windemere, Cumbria (1899).

The roots of the Arts and Crafts movement can be traced to 1851 and the Great Exhibition in London. Held in the eighteen-acre Crystal Palace, the event was a celebration of British wealth, power and know-how, designed to showcase the artistic prowess of a great industrial nation. Queen Victoria who opened the Great Exhibition declared ‘our People have shown such taste in the their manufacturing.’ More discriminating visitors disagreed, seeing the cheap, mass-produced household goods and shoddy ‘art-objects’ as a dreadful indictment on the sad state of British design. Artist Edward Burne-Jones, spoke of the ‘gigantic weariness’ of the exhibition, Pugin described the Crystal Palace as a ‘glass monster’ and Morris dismissed the exhibits as ‘wonderfully ugly.’ For these men the Great Exhibition illustrated there was a clear need for reform.

Britain was the first country to industrialize. Britain was also the first to react against the consequences of industrialization. The Arts and Crafts movement began as a reaction to the squalor, ugliness and inequalities caused by the Industrial revolution — the dehumanization of the worker and the evils of the machine. It was reforming movement in architecture and design that evolved from the writings of Pugin, Ruskin and Morris — but at its core was an over riding concern with quality of life.

The Arts and Crafts movement rejected ‘style’ as an artificial imposition, its designs were distinguished by an ‘insistence on modesty and simplicity . . . And on the inherent qualities of natural material simply worked.’ The architect Phillip Webb, who designed William Morris’s home Red House, exemplified this new point of view. For Webb the land ‘was not merely ‘nature’ . . . and art was not taste but the human spirit made visible.’ He believed that the root of architecture was the land. Before designing a new building, he walked over the site until it ‘relinquished its full possibilities,’ and offered up ‘particular suggestions.’ That ability to weave nature and architecture together revived the quest for an organic architecture. The Arts and Crafts architects successfully ‘recreated the past as a world of pre-industrial simplicity, ‘quaint’ and ‘old fashioned’, whose point of reference was the small manor house, farmhouse or cottage. Houses were no longer built to look new, but old, being irregular, distinct and tucked away into the folds of the landscape which they no longer sought to dominate.’

The movement became aware of itself in 1880’s when it first gave itself a name and it was in that decade that it emerged with recognizable message, it began to flourish in the 1890’s and it achieved its most brilliant effect in the decades around the turn of the century. The term Arts and Crafts, in its own era, signified a general association of like-minded artists, designers, manufacturers and crafts people. And although they were highly individualistic and could not be pinned to a definable style, they shared many ideals: honest construction and simplicity of form, fitness for purpose, harmony between the man-made and environment, the revival of traditional craft techniques and the inherent qualities of natural materials. If forced to pinpoint the four universal principals they would be — design unity, joy of labor, individualism and regionalism — these combined to create the Arts and Crafts approach.

What began as an English movement, eventually found its way to the Continent and America. In Northern Europe designers were inspired but didn’t necessarily follow its model. Only in America was it directly copied, adapted and developed on a parallel tract. The American movement’s zenith lagged a decade, or so, behind the British movement, but both flourished in an age of prosperity, ironically created by industrial achievement. Likewise the movement’s decline can be traced to economic weakness — the Great War in Britain and the Depression in America.

Another difficulty in defining the A&C movement was its universal influence on all artistic expression and design. It not only touched architecture, the Arts and Craft house being the supreme embodiment of the movement, but also garden design, furniture, fine arts, glassware, metalwork, ceramics and textiles. Among its many extraordinary disciples were the architects – Phillip Webb, WR Lethaby, CFA Voysey, Edwin Lutyens, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Charles Ashbee, HH Richardson, Stanford White, Bernard Maybeck, Frank Lloyd Wright and the Greene brothers; garden designers – William Robinson and Gertrude Jekyll; furniture makers – Gustav Stickley and George Niedecken; glass and metalwork – Louis Comfort Tiffany and DirkVan Erp; and ceramics – William Grueby. From jewelry and candlesticks to tea-kettles and clocks, no object of design was untouched by the eloquence of the Arts and Crafts argument, including golf-architecture.

Part III

Country Life

One day in 1896, Edward Hudson owner of a successful family firm of printers, Hudson & Kearns, was playing golf at Woking with one of his business partners, George Riddell, a solicitor with financial holdings in the magazine publishing business George Newnes Ltd. After the round they talked about Hudson’s latest venture, the weekly Racing Illustrated, which looked good but unfortunately was floundering financially. It was then that the idea of relaunching it as a magazine of general interest for lovers of the countryside. And so on January 8, 1897, there appeared the first issue of Country Life.

George Riddell & Edward Hudson

Hudson and Riddell typified the energetic and enterprising set of Victorian London, they were urban commercial animals out to make their fortune. George Allardice Riddell (1865-1934) was enjoying a meteoric career, the son of a Brixton photographer, he was able to push his way up through the legal profession from nothing, making his fortune first as legal adviser and then chairman of the Sunday sensation, The News of the World. Although his reputation was far from savory, he was an influential force within British politics and eventually became Lord Riddell of Walton Heath. He was head of the Newnes publishing company when Country Life was unleashed, and he was also passionate about golf.

But of the two it was Edward Hudson (1854-1936) who would become the dominant force, guiding the magazine for its first thirty-five years. He clearly had a touch of genius about him, despite an awkward nature. ‘Ill educated and apparently inarticulate to a degree that surprised those who knew his gifts as connoisseur and entrepreneur’, he nevertheless exercised an eye for quality. In the same way he collected furniture and art, he collected talented people. From the beginning the emphasis was on quality — in photography, writing, printing and block-making — Hudson took a paternal interest in every aspect of his magazine, according to veteran contributor Bernard Darwin, ‘ his love for it was so palpably moving that to show, even for a moment, a lack of interest in anything to do with Country Life would have been an impossible brutality.’

Country Life billed itself as ‘the journal for all interested in country life and country pursuits’ at a time when eighty percent of the population was urban based, this focus on the country was well timed. Housing within inner London, and the other industrialized cities, was quite bleak and the view of the tranquil countryside, offered by prominent writers and thinkers such as John Ruskin, was a positive alternative. That view followed a long literary tradition, one with which every public-school educated reader of Country Life would have been familiar. That age old image of landed gentry — country gentleman, ancient manor houses and their gardens, tranquil views of an unspoiled landscape — was a powerful one. But by 1897 the aristocracy and gentry were a defeated class, the Third Reform Act had given the vote to the non-propertied working classes, the agricultural depression of the late 1870’s had severely eroded the profits of their great estates and the Death Duties of 1894 had negatively impacted the ease of inherited privilege, the landscape was changing both figuratively and literally. The new rich from the commercial and professional classes could now aspire to that romantic aristocratic lifestyle and Country Life took full advantage of the circumstances, the magazine‘was directed at readers who might well be members of a Surrey golf club. The electric underground and more reliable motor cars provided opportunities for the prosperous to build houses in the still unspoiled rural landscape and enjoy the conventional pleasures of country life, gardening, riding and golf.’

From its first issue, Country Life‘s formula was apparent. A full-page portrait of Lord Suffolk occupies one page. There are illustrated historical account of a country house, sports reports, and a golfing feature. Most prominent were ten full pages of equestrian news, mainly racing and bloodstock gossip. This soon gave way to regular reports and features on other sports, including polo, hockey, cricket, rowing, yachting, rugby, soccer, and cycling. ‘The magazine would carry articles on country houses and gardens, antiques, natural history, traditional country pursuits (most of which seemed to involve killing something) and sporting occasions frequented by high society.’

In the early years the magazine’s impact was primarily visual rather than literary, it was ‘looked at more than read, a consequence of the expertise of the magazines photographers.’ As Bernard Darwin wrote in Fifty Years of Country Life, the magazine was designed to be ‘a weekly illustrated paper of the highest quality that should get the possible results from the half-tone blocks.’ Exacting about quality ‘expense was an entirely secondary consideration,’ Hudson was fortunate in securing the services of two great photographers who established the magazine’s style — Charles Latham and Frederick Evans. Their brilliant images compensated for any initial shortcomings in writing and created Country Life’s reputation for superb photography. Photos that show a remarkable sensitivity to atmosphere and space. Enhanced by the even light and crystal sharp detail achieved by a long exposure, inspired by the English landscape artist Turner.

Soon the quality of writing would match the imagery. The early ‘flowery evocations had been supplanted by historical scholarship based on original research in the case of old houses and by professional architectural criticism in the case of the new. The lead was now taken by the writers rather than the photographers.’ And Hudson had a extraordinary ability to attract contributors whose influence lasted well beyond their own active involvement in the magazine. One of the earliest and most famous contributors was Gertrude Jekyll (1843-1932) whom met Hudson in 1899 and was already a well established figure in the gardening world. Jekyll, an apostle of the Arts and Crafts movement, edited ‘Garden Notes’ for Country Life for thirty years, becoming a landmark figure in the history of twentieth-century gardening with designs that integrated house and garden, architecture with nature. Blessed with painter’s eye, she lifted gardening to the status of fine art — not a surprising result considering her relationship with Ruskin, Morris and many of the well-known artists of the period. She personified the A&C ideal of unity in the arts. Through Jekyll, Hudson met the young architect Edwin Lutyens (1869-1944), who immediately commissioned to build Deanery Garden, his first country house in Berkshire. Jekyll laid out the garden, achieving a perfect marriage of architecture and nature. Icons of an English way of life, Lutyens and Jekyll would team for nearly two decades, creating a new standard of excellence epitomized by the phrase ‘a Lutyens house and Jekyll garden.’ Hudson would again call on Lutyens on three more commissions: Lindisfarne Castle (1902), the Country Life Building (1904) and Plumton Place (1928) in Sussex. The Country Life connection was a tremendous benefit to Lutyens, and resulted in several golf related clients including Alfred Lyttelton’s Greywalls on the Muirfield links and George Sitwell’s club-house at Dr.MacKenzie’s notorious Sitwell Park — ironically Lutyens didn’t play the game. The seductive images presented by Country Life of Lutyens and Jekyll’s work not only ignited their careers, but also fueled appreciation for Arts and Crafts aesthetics in general.

Jekyll’s home–Edwin Lutyens, Munstead Wood, Godalming, Surrey (1896).

There were many other important figures in the early years of the magazine, including H. Avery Tipping (1855-1933) an authority on English interiors, furniture and architecture. He was ‘the first to apply methods of historical research to the subject’ and his articles were genuine contributions to architectural history. His influence brought the country house and garden center stage with the magazine. CL Cornish wrote on natural history. L.March Phillips was a prominent art historian and writer of color theory. Lawrence Weaver (1876- 1930) was another architectural writer. Although Hudson was an great advocate of Lutyens work, the magazine showed little commitment to contemporary architecture. Under Weaver’s guidance, Country Life championed the architects of the Arts and Crafts movement, and sponsored architectural competitions featuring informed architectural critique. He, more than anyone earned the magazine’s title, as ‘the keeper of the architectural conscience of the nation.’ Percy Macquoid was the contributor in the antiques field, he would go on to write the landmark study The History of English Furniture. Editor from 1900 to 1925, Peter Anderson Graham wrote numerous columns, including ‘Country Notes’, ‘Agricultural Notes’ and ‘The Book of the Week’, he was described as ‘a leisurely man of letters rather than a working journalist . . . a dignified unpretentious figure in baggy country clothes.’ And of course the golfing correspondent was Bernard Darwin (1876-1961), the grandson of the naturalist Charles Darwin. Darwin was simply the greatest golf writer the game has ever produced. For nearly fifty years, beginning in 1908, he contributed to the weekly golf column ‘On the Green’, and he also authored the history of the magazine on the occasion of its fiftieth birthday in 1947. Like his architectural colleagues, he too organized a ‘golfing architectural competition’ in conjunction with C.B. Macdonald (judged by Darwin, Horace Hutchinson and Herbert Fowler), with Dr.MacKenzie taking home the first place prize for ‘the best original two-shot hole.’

Tom Simpson’s entry after the fact.

In a few short years not only was Country Life financially successful, but it was successful in depicting a vision of rural life that had enormous popular appeal. ‘Country Life represented a potent image of national identify, embodied in the beauties of the countryside and the past.’ Thanks to the quality of its printing and production, the quality of advertising in attracted and the ability of its writers and photographers Country Life was successful in creating a vision of England that William Morris and the proponents of the Arts and Crafts movement had sought — ironic, considering this vision of a rural utopia was targeted at the privileged. But despite this paradox, the Country Life era was a marvelously optimistic one in which ‘all the arts seemed to moving to a minor Renaissance creating in the process a distinct English style.’

The Guide

Bernard Darwin wasn’t Country Life’s first golf editor, that distinction goes to Horace Hutchinson (1859-1932). The very first issue of January 8, 1897 featured a serialized version of After Dinner Golf, a book written by Hutchinson the previous year. For the next two decades, Huthinson was contributing editor of the weekly golf column ‘On the Green’ — and he was an intelligent choice for not only was he England’s foremost expert on the game but he was also something of a Renaissance Man, well versed in natural history, literature, as well as fishing and shooting, and he contributed pieces on all these subjects. As Darwin wrote, ‘Mr.Hutchinson was a good shot and good fisherman, a capable player of several games and really a great player of one game; but he was much more than this. He was a man of wide reading and culture and of varied interests, to which he was constantly adding to the end of his life.’

Horace Hutchinson

Horatio Gordon Hutchinson was born on May 16, 1859, the third son of a military man — General William Nelson Hutchinson. Horace first attended school at Charterhouse, where his grandfather had been headmaster. He was forced to leave due to poor health and later transferred to the newly established United Services College at Westward Ho!, two miles from the family home in North Devon. As a boy his family had been introduced to golf by his Uncle Fred, Colonel Hutchinson, who lived in Scotland and was Adjutant of the Fife Militia. ‘I used to hear a great deal of talk about this wonderful game, between my father and my uncle, the former having scarcely a more clear-cut idea of what it was like than myself.’ It was about this time that some North Devon locals proposed the golf course at Westward Ho!. ‘The course, as designed by those primitive constructors . . . started out near the Pebble Ridge, by what is now the tee to the third hole. Those pioneers of the game did not even go to the expense, in that instance, of a hole cutter. They excised the holes with pocket knives. The putting greens were entirely au naturel, as Nature and the sheep made them. Assuredly there was no need for making artificial bunkers. Nature had provided them, and of the best. Besides, were there not always the great sea rushes?’

Westward Ho! by Harry Rountree

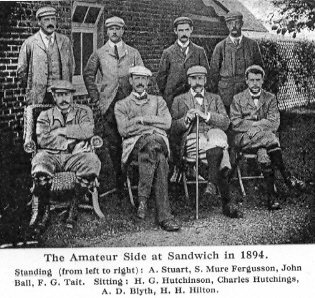

As a boy Hutchinson was given his first golf club by his Uncle Fred. Horace’s anxious mother asked Fred, ‘At what age do you think my little boy should begin golf: I want him to be a very good player?’ ‘How old is the boy now?’ his uncle asked. ‘Seven,’ his mother replied. ‘Seven! Oh, then he lost three years already!’ Horace went on to build a great reputation at Westward Ho! — at the age of sixteen he committed the ‘blazing indiscretion‘ of winning the club medal and by rule was named Captain, obligating him to chair all the club’s general meetings — the rule was amended the following year. In 1878 Hutchinson enrolled at Oxford where he proved to be an excellent all around talent, winning the University Cue at billiards, playing cricket and football, and together with the Scotsman Alexander Stuart made Oxford practically invincible in golf. During extended vacations from school he went on golfing pilgrimages, traveling north to Scotland and St. Andrews, and touring the handful of courses that existed in England — Hoylake, Blackheath, Wimbeldon, Felixtowe and of course North Devon. It was while on vacation from school that he often had as his caddie a young local lad who was also employed in the Hutchinson home — future golf great John Henry Taylor.

In 1882 Hutchinson left Oxford with a degree and the goal of reading for the Bar. Just prior to completing the Bar he began suffering from severe headaches, a continuation of a condition that plagued him his final year at Oxford. The doctors advised that he give up all reading for a time, ‘an instruction which I have observed rather faithfully up to the present’ he would write forty years later. ‘Their very wise counsel gave me all the more time for golf — the rules were not quite so headachy then and a man could play golf, or so it seems to me, with a lighter heart.’ His convalescence was spent at home on the links of Westward Ho!, as well as extended visits to Hoylake and St. Andrews, winning his first of eight St.Andrews medals in 1884. The following year Hutchinson reached the finals of the first Amateur Championship at Hoylake, falling to Alan Macfie, but in 1886 at St. Andrews he beat Henry Lamb by 7 and 6, and in 1887 he won again, this time by a single hole at Hoylake, in a magnificent match with hometown favorite John Ball.

It was in 1886 that Hutchinson launched his writing career with Hints on Golf the game’s first book of instruction. He would later write, ‘I perpetrated a book on golf. The only excuse to be made for it is that it was a very little one.’ Hutchinson originally sent the manuscript to a Mr.Blackwood and who consented to publish it, ‘for I am sure there must be something in that book. Ever since I read it I have been trying to play according to its advice, and the result is I’ve entirely lost any little idea of the game I ever had.’ The first and second edition soon sold out, and they decided to illustrate the subsequent volumes. Hutchinson later wrote that he was dancing with a young lady in London when he asked her if she played the game and she replied, ‘Oh, yes, we all play, and we learn out of a most idiotic little book.’

Hints on Golf was the first of over fifty books that Hutchinson would author. He may have began with golf, but he would ultimately write about almost every conceivable subject — including cricket, shooting and fishing; the subjects of natural history, dreams and mysticism; he was an essayist and a novelist; he attempted detective fiction; he was also very interested in history and wrote numerous biographies; and finally he expressed many of his most personal and intimate thoughts in Records of a Human Soul. It has been said that Hutchinson’s multitude of interests may have actually worked against him, preventing him from concentrating on his strengths.

And as wide and varied as were his interests, so to were his friends and acquaintances. Bernard Darwin wrote, ‘few men have been known to a larger circle or had more affectionate friends than Mr.Horace Hutchinson: he seemed to have been everywhere and to know everybody, and with his handsome presence and graceful kindly manner he had great power of making people fond of him.’ Prime Minister Arthur Balfour was a dear friend, they stalked deer in the forests of Strathconan and played many rounds together at North Berwick. He was very close to Old Tom Morris — Hutchinson’s unorthodox playing style reminded the old man of his lost son Tommy. Famous sportsman, Colonel Secretary and a political adversary of his uncle the powerful Prime Minister William Gladstone, Sir Alfred Lyttelton was a good friend and golfing comrade. Dr.Temple, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Lord Wolseley, esteemed military man and the ‘ill-destined genius’ Oscar Wilde were all acquaintances. The renowned banker, statesman and naturalist Sir John Lubock was another golf partner, Hutchinson would write his biography. He knew the scientists Charles Darwin and Thomas Huxley. He was very close with Sir Thomas Brassey the son of a railroad tycoon. Brassey was a well-known yachtsman and world traveler, as well as a long-time member of Parliament, and ultimately Governor of Victoria — Hutchinson often sailed aboard his famous schooner Sunbeam. And Hutchinson once found himself on the ground and ‘in an eleven’ with the great W.G.Grace, the storied cricketer and quite possibly the most famous man in all of England.

Another of Hutchinson’s very good friends was Cormell Price. Price attended Oxford in the 1850’s where he, William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones met and formed a bond that would last their entire lives. They had fallen under the spell of Oxford’s medieval beauty and John Ruskin’s newly published The Stones of Venice. From that point on they would follow their love of the arts, moving to London after obtaining their degrees, studying under the painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti and joining the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood — the group of artists formed in opposition the formulaic approach of the Royal Academy. Hutchinson wrote the PRB’s objective was ‘to present on canvas what they saw in Nature.’ In 1874 Price became the headmaster of the United Services College at Westward Ho!, the same year Hutchinson began his schooling. It is not surprising that Price as headmaster ‘recommended Ruskin’s books to the boys under his charge at Westward Ho!‘ (Rudyard Kipling was also a student at USC, and he credited Price with fostering his literary ability) The two became lifelong friends and Price’s influence can not be understated. It was through Price that Hutchinson was introduced to Morris, and although two were not friends, Hutchinson became a great admirer of Morris and the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood. Hutchinson wrote, ‘If you look here, there, and everywhere you will hardly rest your eye on an object created since the day of Morris, which is at all worth resting it upon, that does not owe something, and very often the most important thing about it, to his genius. I say this, with full realization that it is saying a great deal. I do not believe that it is saying too much . . . But, apart from this or that form and colour that Morris has given for eyes to dwell on round about us, it is a bigger gift than this, a gift not of details but a general point of view . . . the appreciation that there is actually beauty which can make a difference in our lives. It is an appreciation which we know quite well to have been hid from the eyes of very many of our forefathers.’

In 1890 Hutchinson published what many feel was his greatest literary accomplishment and certainly his best known, Golf from the Badminton series. Bernard Darwin wrote,‘in 1890 he attained his full of stature as golfing prophet with the Badminton. I suppose his teaching is now [1955] largely outmoded, but if other teachers wrote half as well, they would not be nearly such bores as they often are.’ Ironically the publishers of the Badminton Library of Sport, which was a series on sports and pastimes, originally asked Hutchinson to contribute to a volume on Scottish sports, where golf would be included with skating, curling and tossing the caber. He convinced them golf was ‘of sufficient importance to carry a volume to itself’ Hutchinson’s Golf ushered in the golf boom in Britain.

That same year Hutchinson ‘took up rooms in London, near a studio, and began the serious study of anatomy and sculpture as a profession. It was an idea that conflicted a good deal with the whole-souled devotion to golf.’ Unfortunately, or perhaps fortunately for golf, he was struck ill and traveled to Biarritz that winter to recover. Even though maintenance of the course was crude to say the least, the golf at Biarritz — up and down immense cliffs — was invigorating. And although Hutchinson would continue to battle poor health through out his life, the holiday at Biarritz must have provided the medicine he required. When he returned he began work on the first book to depict the great golf courses of both Great Britain and Europe — Famous Golf Links — published in 1891. This beautifully illustrated book evidently satisfied his artistic urges, and golf again became his focus.

Hutchinson’s competitive career also continued. In the 1892 Open Championship at Muirfield he led by several strokes after the first 36 holes, it was the first year the championship was expanded from 36 to 72 holes, he tired and fell away on the second day. He continued to be a fixture at the Amateur championship, as well as contributing periodic articles to newspapers and magazines, and in 1896 he wrote After Dinner Golf in which he created the fictional character Colonel Bogey. At about this time Hutchinson also became involved in the formation of the Oxford and Cambridge Golfing Society. The idea for the Society was suggested at a dinner following a match between some former University players and the team from Oxford. It was modeled after the ‘wandering cricket clubs’ of the time. As Hutchinson described, the Society ‘had no club-house, no green, only a corporate existence and they said to the various Clubs, ‘Now, you give us the free run of your course and a free luncheon and other entertainment, and if you do this we’ll be so good as to come down and play a team match against your members and probably give them a jolly good beating” Horace Hutchinson was the Society’s for president, Johnny Low was the captain, Arthur Croome secretary, H.S.Colt and Eric Hambro were members of the original committee and Bernard Darwin took part in the first match.

It was in 1897 that Hutchinson joined the fledgling periodical Country Life. Writing a weekly column for what would become the lifestyle magazine of Britain — from this platform his influence was immense. And although he covered all aspects of the game — competitions, rules, equipment, etc. — Hutchinson soon began to concentrate on the state of golf-course development, with the games popularity exploding he felt it important to focus on the new art of golf-architecture. Very little had been written about golf design, Willie Park-Jr. had briefly covered the subject in his The Game of Golf of 1896, and the relatively new magazine Golf Illustrated and its editor Garden Smith had touched the subject in 1898, but both were still advocating the formality common in the 1890’s — the static Victorian approach to golf design.

Hutchinson began in 1898 with a fascinating series on Britain’s great links in which he both analyzed and illustrated with photographs the qualities of these venues. The first installment was St. Andrews, followed by Prestwick, North Berwick, Sandwich, Hoylake and Westward Ho!. The final article was devoted to ‘Inland Golf’ and it was at this point that Hutchinson began to exert a critical eye. ‘There is no good reason why the putting on inland greens should not be as good as on any of the classic links . . . You cannot make your bunkers quite as good as the sand-pits by the sea, for these later have the peculiar charm of being Nature’s handiwork, which man can only imitate to a humble degree. If one may be allowed to criticise those shown in our picture (a photo featuring the artificial ramparts at Stanmore), one might say their imitation of Nature’s curves is scarcely as successful as it might be. They err, perhaps in being too stiff and straight. An irregular or S shape of outline would seemed more natural, and also it would have been better for strictly golfing uses . . . rather too uncompromising are these stiff and straight bunkers: and this not a criticism of those seen in the picture particularly, but of the great majority of bunkers artificially planned, for it seems that in only a few instances have our links gardeners had the gift of the artistic eye, or even of the unspoilt natural eye, for Nature abhors a straight line almost as much as a vacuum.’ A diplomatic, but clear critique of the state of golf design; first extolling the virtues of the natural links, followed by an illustration of the current trend’s weaknesses.

From this point on Hutchinson used ‘On the Green’ as a forum to analyze the finer points of design, publicize the work of the new breed of designers and generally promoting his vision of golf-architecture. Certainly there were numerous articles covering all aspects of the game, all the major competitions with special attention to the Amateur and Open Championship, rules and maintenance issues and a major emphasis on the effect of the new golf ball, but a significant percentage of the articles was devoted to new golf courses and the men who created them. Hutchinson brought on Scotsman A.J. Robertson, a talented writer and former editor of Golf Illustrated and a young Bernard Darwin from the Evening Standard. Hutchinson also invited numerous talents to contribute — Herbert Fowler was a regular guest, as was Harry Colt and the foremost greenkeeper Peter Lees, and many of the games great players, including Taylor and Braid. The trio of Hutchinson, Darwin and Robertson, along with the many contributors, provided Country Life with perhaps the greatest golf-writing talent ever assembled — and golf-architecture was a major beneficiary.

In 1906 Hutchinson edited the first book completely devoted to the science of golf-architecture and maintenance — Golf Greens and Green-Keeping. The book, published under the Country Life Library of Sport, gave Hutchinson an opportunity to explore the ideas and theories of the new movement in golf-architecture. H.S.Colt, Herbert Fowler, Peter Lees, C.K.Hutchison, Harold Hilton all contributed, with Horace Hutchinson adding three chapters of his own and providing a comprehensive analysis — weeding through and clarifying any of the inconsistencies of opinion among the contributors. In the book Hutchinson cited his most important tenets in laying out a links, as well as a providing examples of golf holes that illustrate those principles — Eden, Long, and Road hole at St. Andrews, the first at Hoylake, the 17th at Prestwick and 16th at Littlestone among them. At this same time Hutchinson wrote a similar piece for Country Life, a four part series entitled, First Principles In Laying Out Courses, some excerpts:

A question which will be asked is what the ideal mode and disposition of bunkers though the green (as distinguished for the moment, from which guard putting greens) may be. The easiest answer to this is, that variety is always pleasing, and that we do not wish always to have the same kind of shot to play.

Another of the principles which the layer-out of a course ought to place among the guiding maxims is the merit, especially as a guard to a hole, of a bunker running out diagonally into the course.

Bunkers guarding the greens should be deep and small, those through the greens by preference wide and shallow — yet not so shallow as to impose no penalty and make no demand on skill. We do not want to make the game less difficult than it is — rather the contrary — but we want to make the difficulties of such a kind that they give scope for skill in avoiding them and in getting out of them.

Take ‘Hell’ at St. Andrews as a good example of a bunker through the green. It is irregular in form, fairly large in size and has many outlets.

A certain amount of attention has been paid of recent years, in laying out courses, to give some reward to a correct placing of, as distinguished from the more correct directing of the tee shot, so as to make the second shot more easy, or to the correct placing of the second shot, in case of a long hole, in order to make the approach more easy, that is to say, to enable the player to get a run up ‘the entrance’ to the hole, instead of having to loft one or another of the guarding bunkers.

Very little attention indeed has been paid to the value of particular levels and gradients of the ground as practically performing the work of bunkers.

The Chalk Pit at Royal Eastbourne

Sound advice no doubt, but Hutchinson was more than a fine golfer and superb intellect, he was also an experienced designer. In 1886 his father had moved from Devon to Eastbourne in Sussex, and the following year Horace assisted a local gentleman in laying out the original nine of what would become the Royal Eastbourne golf course. The downland course was dominated by two natural features the cavernous ‘Chalk Pit’ and a bordering wood known as Paradise. Eastbourne was also infamous for its wild greens, Darwin would say —‘To putt at Eastbourne is art of itself. It is not that the greens are not good, for they are excellent, but the hidden slopes in them are . . . ‘extensive and peculiar.” One green in particular, the devilish ‘Paradise Green’, was noteworthy for its severe undulations — where according to Hutchinson, one could putt ‘ till the cows came home.’ Hutchinson collaborated with Holcombe Ingleby in the design of Royal West Norfolk in 1892, justly proud of the results he remarked ‘its distinguished features are the absence of artificiality and the great variety to be found in the holes.’ He would go on to design the nine hole links Isles of Scilly (1904) and was twice involved in revisions of Ganton (1905 & 1911), both occasions as part of some sort of gang action, involving the likes of Vardon, Ray, Taylor, Braid, Hilton and later Colt and Fowler. He was also involved at Le Touquet in France. His final design efforts can be found at Ashdown Forest where Hutchinson lived in lovely cottage Shepherd’s Gate (with garden designed by Jekyll) adjacent to the Royal Ashdown Forest course. Early on the banker Hambro, who controlled the land, asked Hutchinson to revise the old course, in fact there is some indication the cottage was a part of his payment, and several years later he would design what became known as the new course. Like Eastbourne, Ashdown Forest was known for its ‘very curly and puzzling putting greens.’ This experience provided Hutchinson with credentials beyond just that of a great player, it was from this foundation that Hutchinson the golf-architectural theorist and critic was able to influence:

The laying-out of golf courses is such a perpetual process that we need offer no apologies for a further hint or two on that inexhaustible subject. There is one point which even the most advanced of the links architects seem often to have missed. It is in respect of the right placing of bunkers through the green for the punishment of the indifferent tee shot. Very often we see bunkers place on the right-hand side of the course and another on the left-hand side, with a channel left between them down the centre . . . This is an arrangement which has neither equity nor interest. If one of these bunkers, it does not matter which was pulled back some fifty yards nearer the tee, so as giving a chance of carrying it, it is obvious at once — that the shot would gain interest.

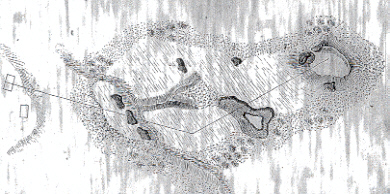

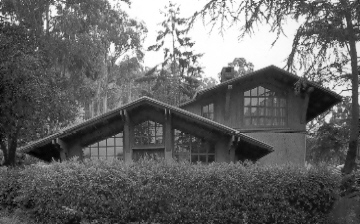

Natural features dictate play at Royal Ashdown Forest.

Too much of a dead level is unprofitable, and here and there, say twice in the round, we may even do with a ‘blind’ shot. If it be a long one . . . And then we should remember that, since we seldom play in a dead calm, we shall get much more variety from a course which dodges here and there, with holes across and right angles to one another, than on one which goes straight out and in so the that the wind is coming at the same angle all the outward half, and, again, at the same angle (opposite the former) all the inward half.

‘A good natural course’ is rather a hackneyed expression by this time, and yet to apply it is, on the whole, to praise highly. We know that if we go to a course that is so described we shall almost certainly have a pleasant day . . . Naturalness in a course also implies holes guarded by natural hazards, and more particularly by natural turns and twists in the ground designed by the hand of Providence to tease the cut-and-died approaches.

We are in danger of monotony on the course which any one of these, or other, artificers plans for us, because they follow good principles too religiously. My view is that a bad hole here and there, such as a pot hole — say, the seventeenth at Sandwich — is not out of place at very rare intervals. Even over a golfer who is all good we rejoice when he makes a lapse. Some years ago the idea was at every hole to give a man a cross bunker to pitch over. Then it was realised that this was not a good principle for repetition eighteen times in succession. There was an outcry against such bunkers, and now the tendency is never to give us one at all. That is a mistake. We want at least a couple of them in eighteen holes, according to my way of thinking.

Schools of golf architecture are divided into the disciples of those who make grass-sided bunkers and those who make them with a steep cliff of the local soil. But why make all of one kind or the other? Why not a mixing up and variety?

The first thing to appreciate, by way of shield against this danger, is that the sauce of golf is its variety. When you hear this wiseacre and that saying that there ought to be no cross bunkers, another that there ought to be no running-up shots, and so on, you may know at once they must all be wrong. Such worlds as ‘none’ and ‘all’ should not appear in the laws laid down, for these matters. We want a little of each — ‘two pen’orth of all sorts,’ like the cabman’s morning drink — some lofting approaches, some run-up and so on with the rest of the puzzles.

In any case that is the right end, that a tee shot, if placed correctly, shall give an easier second, than if not correctly placed. It is an idea to be held in my mind by all planners of greens, second in importance to one other, namely, that no one idea shall be allowed to obsess the mind in so planning to the exclusion of others. It is the following, without relaxation, of one idea, however good in itself, that makes courses dull with all the dullness of artificiality; it is only by combining all ideas that are not bad that one can get anything like the infinite variety of Nature.

Brancaster

Hutchinson’s theories can be summarized as follows. He believed that a limited amount of blindness was acceptable, but never blind approaches, but then excuses an occasional blind approach if they are ‘full shots’ or long approaches for the ‘sake of interesting variety’ , he felt there was place in the game for what he called ‘pleasurable uncertainty.’ He condemns as a rule cross-bunkers, promoting diagonal bunkers and bunkers en echelon (or staggered bunkering) because of the choices they provide, but then at the same time he says don’t take this too literally because the aerial shot is exciting and variety is king. He believed that a well designed course should give the accurate driver ‘the just value for the correctly placed shot,’ but at the same time was not opposed to severely punishing an inaccurate approach. He promoted the use of ‘floral hazards’ — especially as side hazards and the corner of doglegs — at time when a tree on a golf course was thought to be blasphemy. He promoted the incorporation of the native surrounds, the use of whins, heather, long tussocky grass and other native growth between tee and fairway ‘to catch and punish a topped drive’ and around the margins of the ‘mown and well-kept sward, between the ‘pretty’ as modern people are in the fashion of calling it, and the ‘ugly’ original jungle.’ Hutchinson was a was major proponent of the idea of ‘the ugly original jungle‘ — ‘the bent grass looks a bit artificial and regular, but no doubt in time it will look as wild and terrible as need be.’ One could almost conclude that Hutchinson contradicted himself on almost every important point, but that apparent paradox is understandable when you consider his overriding rule for interesting golf-architecture was variety. He believed the ancient links were interesting because of their variety, variety which was a result of a natural evolution, and that man-made rules for design must be flexible to account for the haphazard nature and unpredictability of Mother Nature.

Not only was Hutchinson instrumental in elevating the art of golf design, he was also actively promoting the artists whose work he admired. ‘What I should rather like to see is a golf course laid out and bunkered by consigning six holes to Mr.Colt, six to Mr.Fowler and six to Willy Park. I name these because they seem to me to have the most distinct and different styles.’ Hutchinson also provided a forum for many architects to express there thoughts and observations, allowing them to contribute on a regular basis. Fowler was a frequent guest, writing about every thing for plastisine models to analyzing the Open venue at Deal to defending the criticisms of his work at Westward Ho!. Colt was equally active, interestingly even contributing an article on club-house architecture. Harold Hilton, J.H.Taylor, Tom Simpson, Alister MacKenzie, C.K.Hutchison, John Low, Stuart Paton, John Abercormby, and C.B.Macdonald were either contributors or the subject of major features. James Braid produced a three part series on ‘The Planning of a Golf Course’, in which he put forth his very formulaic approach to design, which was followed the next week by a short rebuttal by Hutchinson, ‘We are becoming a little wiser than we used to be, and Braid’s recent articles show especially how much wiser our professional brethren are becoming than they used to be, in the problems of laying out courses. We have hunted the matter much closer down to its first principles and realise much more fully the qualities which make a course difficult, interesting and a good and just test of golf. There is only the fear that as we become more scientific we may fall into the worse pit of becoming altogether undramatic. It is not the least necessary that it should be so: if the science is applied properly it ought to have the effect of adding more than a little to the dramatic interest; but unless that interest is kept before the eye of the linkscape gardener he may turn out a good, but deadly dull job.‘