The Challenges of Restoring a Classic American Golf Course

by Kevin R. Mendik,

National Park Service, Northeast Region

March, 2007

Kevin R. Mendik is an Environmental Protection Specialist with the Northeast Region of the National Park Service where he has worked since 1990. Much of his work is in the area of environmental compliance and permitting for NPS park projects. He was formerly the Conservation Administrator for the Town of Lexington, Massachusetts where his primary responsibility involved compliance with the Massachusetts Wetlands Protection Act. He holds a Law Degree and a Masters Degree from Vermont Law School and is a member of the Massachusetts Bar.

His first published golf article was written for the 2001 Annual Issue of Commonwealth Golf about the Highland Links course in Truro, MA, which sits inside the Truro Highlands Historic District and is also within the boundaries of the Cape Cod National Seashore. He has since written for numerous state and regional golf publications as well as the Golf Collectors Society Bulletin.

He plays exclusively with original hickory shaft clubs from the early 20th century and his favorite courses, not surprisingly include, National Golf Links of America, the Myopia Hunt Club, the Cape Arundel Golf Club and his home course, the Pine Brook Country Club, where he sits on the Greens and Grounds Committee.

His youngest son’s initials are not coincidentally, C.B.M. and his home overlooks a classic American golf course.

Author’s Note: This paper was presented at Preserve and Play: Preserving Historic Recreation and Entertainment Sites, held in Chicago during May of 2005. A condensed version was published in November of 2006 in the proceedings from that Conference. For more information please contact the Historic Preservation Education Foundation, P.O. Box 77160, Washington, D.C. 2003.

The 15th hole at the author’s home club of Pine Brook Country Club, another New England Stiles gem.

Introduction

The restoration of a Classic American golf course has all the elements and technical challenges of restoring a historic structure or a cultural landscape within a unit of the National Park Service. The period of significance must be established, contributing elements such as greens, bunkers or entire holes must be identified, architect’s drawings and plans must be obtained, historic photos and historical society records are sought, and core samples are taken.

However, there is one big set of differences between most golf courses and any of the 390 sites within the National Park System: golf courses do not have an Organic Act, although many predate the establishment of the National Park Service in 1916; they do not have Director’s Orders to guide them in their planning efforts or environmental compliance methods; they do not operate under General Management Plans (GMP). They do not have to draft Environmental Impact Statements which go through public review. Most courses do not have friends groups to assist them in their financial matters, or to lobby on their behalf before Congress. They do not have Federal, state and even local sources of funds and other assistance such as local historical commissions and community preservation acts.

If a club decides to undertake a restoration, they may be subject to local and state laws which prevent its execution, such as wetlands laws. Many of the classic American courses are extremely private, and the public has no physical access or input into the club’s management decisions. Even an attempt by the public to place a course or element of it on the National Register of Historic Places can be effectively blocked by the owner or members through a formal objection. While the NPS’ primary mission is laid out in the Organic Act and directs us “to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations,” there is simply no unifying set of guidelines for golf courses, pubic or private. Impairment to the historic fabric of an old golf course designed by one of the pre-eminent golf architects of the early 1900’s is not the subject of wide-ranging scholarly discussion or even debate in most cases, but it should be.

Relatively few courses or features on them are listed in the National Register. If they are, it is often for the clubhouse or a particular feature. In many cases the membership or government entity that runs them has no cognizance of the original golf course designer, clubhouse architect or of the landscape’s potential historic or cultural significance. Clubs do not have to consider Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act when they decide to undertake significant changes on the golf course, even if their clubhouse is on the National Register. Fortunately, some clubs do have a strong sense of their historic context in the game of golf and have either actively maintained their historic fabric over the decades or have undertaken restorations based on original plans, period specific aerial photographs, club records and other valuable sources of information. Some have initiated the process for inclusion onto the National Register. Others have let their past fade away into oblivion and would not even be recognized by their original designer; in some cases, that person is unknown.

There are a few individuals who together designed or worked on the majority of courses from the Classic Period and pioneered the techniques of American golf architecture. It should be noted that the concept of golf architecture did not really exist until roughly 1911 when Charles Blair Macdonald’s masterpiece, the National Golf Links of America (NGLA) was officially opened. Even the term “Golf Architect” did not exist until Mr. Macdonald coined it for himself. The concept of designing a golf course and imposing it upon the land, as opposed to fitting a golf course to the existing terrain, was effectively developed by Mr. Macdonald during the process of designing NGLA. Having concluded around the turn of the century that there were simply no “first class” golf courses in America comparable to the classic courses of Great Britain and Ireland, he decided to change that. He spent much of 1902 through 1906 abroad and returned to the United States in 1906 with surveyors’ maps of the more famous courses, plus 20 or 30 of his own sketches of courses with distinctive features. Some called his idea of essentially copying the great holes humorous, while others thought it visionary. Macdonald’s definitive statement on the matter was, “The flowers of transplanted plants in time shed a perfume comparable to their indigenous home.” He eventually realized that some of the outstanding features of the blueprinted holes could be woven into or adapted to the terrain, in some cases lengthening or shortening the original hole. Other holes he simply created. The resulting golf course was far superior to virtually anything that existed in the U.S. at the time, and clubs all over the country, especially next door at Shinnecock, were clamoring for his design services. He never charged a fee.

Macdonald’s Ballyshear home with its proud view over National Golf Links of America

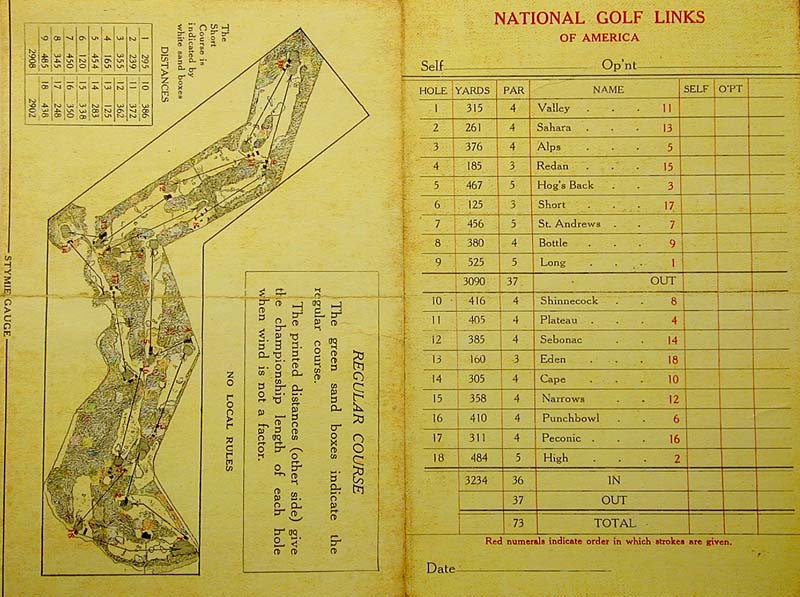

A 1921 scorecard from National Golf Links of America

Most Classic period golf architects had no training in landscape design, with one notable exception being Wayne Stiles, who worked as a landscape architect and city planner before embarking on a golf architecture career. Seth Raynor was a surveyor in Southampton and was hired by Macdonald initially to conduct surveying work on the propberty that was to become NGLA. Among the more well known is Donald Ross, who is credited with over 300 designs and renovations. Others include A.W. Tillinghast, Seth Raynor, Walter Travis, Tom Bendelow and Dr. Alister MacKenzie, the architect of Augusta National. Mr. Macdonald, largely considered the Father of American golf architecture, played in the first formal U.S. competitions, winning one, and was instrumental in founding the United States Golf Association (USGS), yet he is relatively unknown simply because only 9 of his designs are extant and are with one exception, exclusive private clubs. A recent book on Mr. Macdonald sold only a few thousand copies, and many of them went to club members at courses he designed. One of Mr. Macdonald’s courses was sold for development on Long Island in 1985. Entire books have been devoted to lost courses, many of which disappeared with little or no notice from historians or landscape architects. Each of these gentlemen recently had books written about them, so ensuring the integrity of their surviving designs is far more likely. They have also written books or had significant writings identified.

North Haven Country Club in Maine is a well preserved Stiles course.

This year’s U.S. Open is being held at a Donald Ross designed course, Pinehurst No. 2 in North Carolina, and there exists the Donald Ross Society, dedicated to preserving his courses and materials. A.W. Tillinghast also has an organization dedicated to his work, known as The Tillinghast Association, and there is also the Seth Raynor Society. His courses are also well known for top level competition, including the Lower Course at Baltusrol, site of this year’s PGA Championship and Bethpage Black, site of the 2002 US Open. Even so, these organizations are only 16 and 7 years old respectively, considering that today they are essentially the most well known golf architects of the Classic Period. Go back roughly 20 years, and relatively no one knew about Ross or Tillinghast.

However, there are others from the late Classic and Golden Age period (primarily the 1920’s) that are still mostly unknown, and it is considerably harder to ensure that the historic fabric of their work is protected. One example is Walter Travis, despite the recent publication of his biography and the establishment of the Walter Travis Society in 1994. An example of this is Wayne Stiles, who is relatively unknown compared to Donald Ross, yet they both worked in the Northeast during the teens and 1920’s. Mr. Stiles designed roughly 60 courses from Maine to Florida, was a Fellow of ASLA, designed entire towns and worked directly with the Olmsted Brothers, as did Mr. Macdonald and his associates. The first examples of golf course designs being laid out in combination with resort or vacation home communities arose as a result of these collaborations. It was not uncommon, especially in the late teens and 1920’s for wealthy individuals to commission nine or 18-hole golf courses on their sprawling country estates. Some of these courses were never built, others disappeared, others became private country clubs or in some cases public courses. Through these collaborations, the design of Classic American golf courses and the field of landscape architecture became inextricably linked.

Cape Arundel’s design by Walter Travis is famous for one of the finest sets of greens in the country.

The Old Man’s tombstone with two Schenectady putters.

Unfortunately, just when the Classic Period had turned into the Golden Age during the 1920’s and 500 courses a year were being added to the landscape, the Depression and WWII arrived, resulting in a virtual halt to golf course development from the mid-1930’s until the late 1940’s. The following 40 years saw a tremendous number of courses remodeled. Hickory shaft clubs had largely given way to steel shafts by the 1930’s, the golf ball was flying farther than ever due to technological advances, many courses barely survived the Depression so bunkers were lost and greens reduced to save on maintenance costs. An aging membership roster at most clubs also led to changes to simply make the courses easier to play. Most prewar courses had no irrigation systems and adding them was often done without regard for their historic integrity. The scientific and engineering advances and construction techniques that emerged from the Depression and WWII all combined to allow for unprecedented changes in the American golf landscape. Then of course, there was the introduction in 1954 of the golf cart, which not only placed additional physical burdens on the turf, but allowed designers and greens committees to conceive of new courses and changes that were previously unheard of. Tees could be considerable distances from the previous green, substantial elevation changes became commonplace and courses appeared in locations where all but the hardiest walking golfers and their caddies feared to tread. It was not until the 1980’s when the concept of golf course restoration even took hold. By then, many courses had completely lost their historic fabric and the memories that went with them. Documentation of a club’s history often ended up in dumpsters or at best damp basements.

Chapter One: Primary Causes Contributing to the Loss of a Golf Course’s Historic Fabric

1. Landscaping

Simple things, such as the planting of trees, flowers, shrubs and grasses can have significant impacts over time. Many classic period courses had no trees, as most of New England had been clear cut by the mid to late 1800’s. It was quite rare for a Classic era course to have a planting plan to accompany its construction. Trees planted in subsequent years or decades, especially around greens and trees, make growing and maintaining grass far more difficult. That combined with changes in maintenance equipment, resulted in alterations of green shapes and sizes. It is far easier to mow in a circle than a square, and as a result, many tees and even greens initially laid out as square or rectangular have become rounded, thus altering the architect’s vision or style. Trees and other plantings can change the shot value of particular holes, or they can alter the wind, as with privet hedges. Many classic courses have or are currently going back to virtually treeless conditions, such as the Myopia Hunt Club, Shinnecock, NGLA and the Oakmont Country Club, site of 7 US Opens from 1927 through 1994, but it is not an easy sell to either the members or in many cases, local authorities. At Baltusrol, literally thousands of conifers were planted by a green committee member who got them post war for virtually nothing. According to A.W. Tilinghast, Walter Travis was of the opinion that trees had no business on a golf course. Donald Ross was also thought that there was a limited place for trees in golf. Aerial photos over the decades from the Springhaven CC in Wallingford, PA show an initially treeless course in 1927, numerous plantings coming in by 1940 and the 1995 view of a park like setting. Aerial photos of Augusta National show a similar progression.

Changes in the types of grass seed have emerged over the years to the point where many educational institutions have advanced degree courses in golf agronomy. In fact the USGA has its own agronomy department. Bluegrass, velvet bentgrass, hybrids and other grass types have transmogrified acres and acres of greens and fairways that did not exist when courses were designed, creating a host of challenges for greenkeepers. The type of mowing equipment evolved over the decades to the point where green speeds have gotten considerably faster than when courses were designed, in some cases necessitating removal of some of the wonderful mounds and swales that gave them their character or were designer signatures. Introduction or removal of fescues along fairway edges, and even the seasonal way in which it is cut, can alter the play and character of a golf course. Some courses still resort to seasonal burning and hand weeding of rough to maintain their conditions. Flowers and shrubs in some cases are a character defining feature, such as the famous azaleas at Augusta National. That is an example of a course that was designed to be a park like setting with numerous specimen trees and shrubs imported from around the world. They have a horticultural staff to deal with just the landscape plantings, which is not unheard of. However, for most courses, the planting of trees many years or decades after the original design, often results in the perceived need to further change the golf course to accommodate the trees, which in so many cases, the members love.

2. Architectural

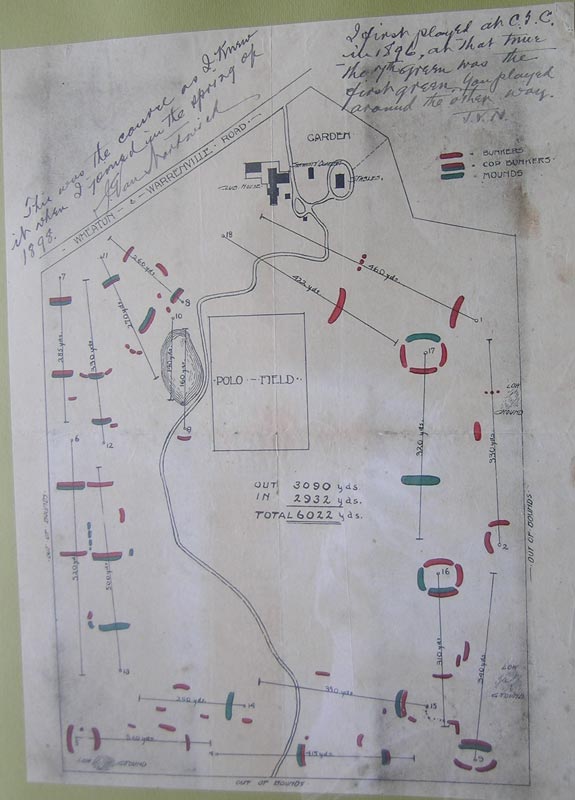

Many of the earlier layouts (pre-1900) were not much more than a stake placed at a green location, which also served as the next tee. Mowing was whenever sheep or cows could be induced to eat the grass. These “layouts” were often represented by drawings of straight lines connecting squares and circles. Most early clubs don’t have actual plans, but have renderings made in some cases, from early course descriptions. Courses changed locations frequently in their early years (this continues today), making it even more difficult to track the evolution of a course or identify an architect’s signature features.

Herbert C. Leeds of Boston, the architect of the Myopia Hunt Club in Hamilton, MA became a member in 1896 and was quickly asked to lay out what was known as the Long Nine. He did so “with a determination to make the Myopia Links as testing as the lay of the land permitted and never to settle for a level putting surface when undulations or a slope were available.” This is an example of one of the first efforts at actually designing a golf course and it was widely considered one of the finest in America at the time, and was regarded so highly as to warrant hosting the 1898 U.S. Open. It was held there again in 1901, 1905 and 1908. Even so, Mr. Leeds continued to expand and tweak the course for decades. On many occasions over the years, he was known to observe some of the club’s better players and visiting professionals and place hazards where they were hitting their good shots, just to make the course more challenging. Newspaper accounts from the early 20th century describe the course as a “Classic Links” and one of the only first-class courses in the Boston area. Myopia usually posed quite a challenge to the top area golfers who found the distances longer and “the problems more complex” than those they were used to. Another account from the same year notes that Myopia was “more difficult than ever with new traps and bunkers.” These kinds of alterations retained the historic fabric of the course because they were undertaken by the original architect in response to changes in equipment (especially the new Haskell ball) and improving players, as opposed to a greens committee decades later.

At the Essex County Club in Manchester, MA, the initial layouts of 1893, 1894 and 1895 were according to their own centennial history “rudimentary and impermanent,” but were typical of courses in those days. Essex’s first professional, Tom Bendelow of Aberdeen, Scotland, directed the layout of a proper course in 1896. He constructed features, such as cross bunkers and mounds called chocolate drops, but his initial greens at Essex were flat and square. He had also reworked New York City’s Van Cortland Park in 1895, the first municipal course in the country, into a nine-hole golf course. He reused many of the stone walls as fairway and greenside mounds. This might be considered the first instance of adaptive reuse of natural materials in golf course design.

Donald Ross worked at the Essex County Club from 1908 through 1917, completely reworking the 1896 Tom Bendelow course. During most of this time, he constantly redesigned or reconstructed his own work. At Pinehurst #2, site of this year’s US Open. Mr. Ross is known to have made changes to that course over a dozen times. Again, these changes were similar in kind to those of Leeds at Myopia, were done by the original 18 hole architect, and were in response to changing conditions and equipment. Essex and Myopia appreciate their places in American golf history and continue to maintain their historic conditions.

When plans were actually prepared (this was not widespread until the late teens), the clubs often didn’t adhere to every element. That may have been the result of financial factors or physical considerations, such as encountering ledge where a green, bunkers or other key feature was proposed.

It was quite rare to have an as built plan in those days. However, with changes in construction equipment since then, and an architect’s original blueprints, the intended design might be able to be restored quite accurately. That of course, depends upon such relatively modern factors as environmental laws and natural features like wetlands and watercourses. Even constructing a haul road to accomplish a restoration can be problematic in those cases.

Many clubs simply don’t know who designed the course or have only anecdotal evidence that certain architects may have been there. In fact, it was not uncommon for an architect like Ross to never even visit a course he designed; he often simply worked from topographical plans. He is credited with 413 courses and revisions, and by 1925, had 3,000 people working for him. Others, such as Stiles, credited with fewer than 60 courses, often spent weeks at a course, walking the land and “laying out the course with his eyes.”

During the late Classic Period or Golden Age, the great architects often made changes to each others courses. Many of the architects working during the booming 1920’s obliterated work of their contemporaries. Even the Chicago Golf Club, site of the 2005 Walker Cup Match, one of the five founding member clubs of the USGA and the first 18-hole layout in the country dating to 1895, has seen its share of changes. Seth Raynor, Macdonald’s surveyor and long time associate renovated the 1895 Macdonald course in 1922, and there is still disagreement as to whether today’s course is properly labeled a Macdonald design or should be attributed to Mr. Raynor. Today’s scorecard lists both. Architect and course restoration specialist Tom Doak has been working with the club for several years, working from aerial photos and archaeological evidence to restore greens and bunkers back to their original configurations.

A 1898 drawing shows Macdonald’s original layout at Chicago Golf Club.

The Classic era architects often completed for lucrative contracts, but when the Depression hit, golf design work all but dried up. During the Depression, Ross, Stiles and Tillinghast all designed courses for the Works Projects Administration. These include the courses at Bethpage State Park in NY, site of the 2002 U.S. Open and Riverside Municipal GC in Portland, ME. There are many courses that can point to half a dozen architects or more having worked at their course at various times. The Hartford GC in CT is a great example of this, yet the entire property is listed on the National Register. Another example is Shinnecock Hills in NY, also listed on the NR, which has undergone numerous changes and seen many designers. Others may only have a hole or two that retain any historic character. Some courses have nine or numerous holes legitimately attributed to a particular architect, but there is no direct proof as to which ones.

3. Technological Advances

Today’s golfers, both at the professional and casual level, have benefited from advances in equipment and conditioning methods like never before. This has resulted in many classic courses altering their layouts or simply lengthening them (as has Augusta National) to adapt to the longer and longer distances being achieved by professional golfers, sometimes every year. Nowadays, only courses well over 7,000 yards can accommodate a professional event, whereas most courses designed during the classic period were roughly 5,000 to 6,500 yards. Even the casual golfer can hit a ball 250 yards, thus taking many turn of the century hazards out of play.

With the use of dynamite and heavy equipment, architects such as Ross and Macdonald could design courses to be imposed on the land, and they, as well as others, could also make significant changes to existing courses that had previously been deemed unworkable due to physical conditions. Even today, architects often look to the classic era designs when laying out holes or setting up greens. The concept of a Biarritz green, a Redan par three, false fronts, fairway cross bunkers, turf faced bunkers, saddle greens or opposing fairways slopes is still very much in vogue today.

The USGS and the Royal & Ancient Golf Club of St. Andrews have and continue to address issues such as the Spring-Like Effect of drivers and the distance capabilities of golf balls. Numerous changes to golf clubs and the golf ball that have occurred in the last 125 years have collectively altered the way the game is played and the way courses are designed and altered. This is far from a recent phenomenon, and continues to be addressed by course superintendents today.

The evolution of the golf ball likely had the most impact on American courses, especially at the turn of the century. “But, suddenly, out of the blue, came a bolt which upset all calculations. An individual by the name of Haskell discovered that if you wind a core with thin rubber bands, and enclose the whole in a rubber shell, you then have a ball which will carry many, many yards farther. The result was that our course became, almost automatically, antiquated and inadequate.” This reference is to The Country Club’s (TCC) first 18- hole layout from 1899. Mr. Haskell patented the wound ball that year. Over the next several years, the use of the Haskell ball dramatically changed top level competition, and necessitated changes to the courses themselves.

All of these changes have had an enormous cumulative effect on the way architects restore classic courses, redesign them and design new courses. In so many cases, the clubs themselves have undertaken substantial changes to keep up with emerging technology, preferences and trends.

4. Personal Preferences of Members, Boards and Committees

Courses from the classic period have endured wars and depression, boom and bust cycles and now environmental regulations. Over the decades, the personal preferences of members, Greens Committees and Boards of Governors have done so much to alter the historic character of so many golf courses, that the impact is simply incalculable. This is hardly a new concept. Writing in 1933, Dr. Alister Mackenzie stated that “[c]ourses are ruined by the well-intentioned but injudicious attempts of their green committees to improve upon nature.” This view is still alive and well, especially in regards to classic tournament venues, among them Augusta National.

In many cases there may be a clubhouse or other physical feature on a golf course that has found its way onto the National Register, but in the vast majority of cases, there is simply no regulation or oversight of the golf course itself. Lack of any kind of master plan for a club is the rule rather than the exception and changes are often made with no consideration of their impact on historic features that may not even be recognized as such. Members with no formal training in landscape architecture or golf architecture can often cause substantial changes simply because they are in a position of power at “their” club and want to make some changes that better suit their game. Members invariably get older and getting in and out of some of those deep bunkers becomes more and more difficult. As a result, classic era bunkers are often the first design element to lose their historic integrity. At myriad American clubs in the decades after WWII, aging members wanted to adapt their now summer courses in New England to the style of their winter courses in Florida, Arizona or Nevada to name a few, resulting in a whole genre of changes that erased so much of the pre-War American golf architecture.

Clubs often bring in an architect to rework a course; perhaps to change drainage issues or other elements that are no longer to the members liking. That architect and the club itself may have no regard for the original architect’s vision. Original plans may not even exist or can be extremely difficult to locate, so even a well intentioned club may not be able to recapture its past even with the clear recollections of long time members. Fortunately there are clubs that have and continue to decide to restore their course, and there is a small but committed group of golf architects who concentrate on restoring classic golf courses and designing new ones in the classic style.

5. Changes to Physical Surroundings

Many courses that were laid out in rural locations find themselves decades later in a suburban or even urban environment which brings along alterations such as shading from buildings, changes to drainage and water supply, invasive vegetation and both the removal and introduction of animal species. Roads and railroads have often altered courses, and even resulted in their changing locations, sometimes repeatedly. Many courses were built by and for railroad magnates, but over time, those little used private tracks have become major passenger and freight lines, further altering the character of the course, and in some cases causing irreversible changes or forcing relocations.

Homes behind the great Redan green at Chicago GC alters the hole’s overall appearance.

6. Changes in the Regulatory Structure

Most of the classic period courses were designed and built in the days when there were no environmental laws or regulations. These courses rarely required any type of permit, other than perhaps a planning board approval if there was one at the time or an engineering review. Golf architects and construction foreman had relatively free reign to deal with the types of issues that would make them unbuildable today. Other modern legal obstacles abound. Certain trees may be rare or contain rare species, thus preventing their alteration, even if they adversely impact the ability to maintain a key area, such as a green or tee, that in many cases, long predated the planting of the subject tree. Even mowing practices, especially in the rough, can be limited based on rearing characteristics of resident species. Some courses are taken over by municipalities or parks departments, which then impose their own constraints, both budgetary, legal and design related.

Case Study: Blue Hill Country Club, Canton, Massachusetts

Today’s regulations often make it difficult if not impossible to restore courses to their desired condition. Wetlands or T&E species can prohibit some work outright. In 2001, the Blue Hill CC in Canton, MA, site of the 1956 PGA Championship, embarked upon a full scale restoration of their 27-hole layout. The first nine was designed by Skip Wogan, who succeeded Donald Ross at Essex, and Blue Hill was one of his first independent designs. The second nine was completed in 1933 and fortunately the club was able to obtain aerial photos from that period which guided the restoration. The third nine was designed by Skip’s son Phil Wogan in 1955, and also had relatively good documentation for its original layout. The course had been subject to much of the kind of attention or lack thereof as previously mentioned, yet the project took almost two years to get the approval of the members. Many wanted the course to stay the way it was, which resembled many Florida style courses with flash sided bunkers rising above the greens. Forty two bunkers that had been eliminated over time for various reasons were restored during the work. However, sometime in the course of approving the plans and moving forward on the physical work, there was substantially less than perfect communication between the club and the Town of Canton as to the wetlands aspects of the work. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts has arguably the strictest wetlands laws in the country, and in many cases, municipalities have even stricter local wetlands By-Laws.

An example of wetlands preventing a full bunker restoration at Blue Hill.

One result of this glitch was significant time and cost overruns. Work begun in wetland resource areas during the early part of 2003 were required by the Town of Canton Conservation Commission in early 2005 to be brought back to its pre restoration project condition. From an initial wetlands compliance budget of roughly $25,000, the costs associated with completing remedial work, additional permit applications, legal and consulting fees, and contractor changes, ballooned to well over $800,000. This necessitated scaling back on other restoration work, such as the removal of numerous large trees near greens and other key features. Originally planned to commence in the fall of 2002 and be completed by late 2003, the project is still ongoing. The last element to be restored on the main course, the 16th green complex, was completed in May of 2005. Unfortunately, the work proposed for the 8th green and 9th tee on the 1955 course, has been postponed indefinitely, resulting in a restoration of 26 out of 27 greens and tees. In other locations, proximity to wetland resources prevented the restoration of historic bunkers, green complexes and tees.

Progress continues to be made at Blue Hill, as witnessed by the vastly improved bunkers.

Chapter Two: Determining the Period of Significance

The NPS Model for Restoration

With so many changes having occurred over the decades, if a club does decide to embark on a restoration, they must pay careful attention to the first and probably most important decision they will make: what is the period of significance to which the club is seeking to restore? This is the same question that faces the NPS when preparing a GMP or embarking upon a physical alteration or interpretive plan for a contributing resource within a park unit. The NPS; however, has legions of experts in various fields and often has substantial documentation as to a property’s historical significance when it is brought into the NP system. We put together myriad documents to identify the park’s resources and plan for how to protect, manage and interpret them; including but certainly not limited to: Cultural Landscape Inventories (CLI), Cultural Landscape Reports (CLR), Historic Structures Inventories (HIS), Lists of Classified Structures (LCS), Natural Resources Inventories (NRI), Collections Management Plans, Long Range Interpretive Plans and Vegetation Management Plans. All these and more are carefully analyzed and synthesized by planning teams and are prepared and evaluated in preparation for developing and/or implementing elements of a GMP. We need to identify the resources, natural, structural, landscape, collections, etcetera, that contribute to the historic, natural and cultural significance of the unit. In some cases, before we can even get to that stage, the NPS needs to determine the specific period of significance (or in some cases periods) to which we want to manage the resources.

At some parks, that is a relatively simple question; at others. It’s a bit more complicated. Probably the most notable example is the Highland Links GC, located within the Truro Highlands Historic District of the Cape Cod National Seashore. Not only do they have to deal with physical environmental constraints, such as wetlands and coastal habitat, but they’ve got the entire bureaucracy of the Federal Government to watch over their every move. In Highland’s case, that has been a good thing, as the course remains in largely its original condition, although the lighthouse was moved much closer to the 7th green, but that was to keep it from falling into the Atlantic Ocean, and because it’s on the National Register.

The Golf Course Model for Restoration

There are simply no specific guidelines or regulations that a golf course has to follow if it decides to embark on a historic restoration. If a club decides to restore the course, then they have to answer some fundamental questions similar to what we face at the NPS: What is the period or periods of significance to which they want to restore; who is that architect and what was his style. Do they want to restore the original layout, which for most classic courses is less than 18 holes and may predate 1900; does the club want to restore an early 20th century 18-hole layout designed by one of the period’s prominent architects, which may have eliminated the pre-1900 holes; do they want a combination of both, or is there some other preference or determining factors such as environmental regulations.

Chapter Three: Research methods to determine historic conditions.

In some rare cases, original blueprints for courses exist and even original individual hole blueprints. There are many aerial photographs from key periods in a course’s history that may be available, if you know where to look. Club staff or members may have photographs from various periods; they also may have good memories. Historical documents may exist, such as contracts with architects, bills paid, committee minutes, town records for permit applications or plans filed for various purposes, historical society records or old newspaper articles. In other cases, there is simply little or no information available. As for the standard tools, the best sources are photographs, as courses often did not get constructed exactly the way they were laid out on plans. From these bunker and green shapes and locations can be clearly identified in some cases. Further groundtruthing of bunker characteristics can resemble an archaeological site, with core samples taken to identify layers of sand.

A few great sources exist for aerial photos. One is housed at the Hagley Museum and Library in Wilmington, DE, which houses the Victor Dallin Aerial Survey Collection. Between 1921 and 1941, J. Victor Dallin ran a company called Dallin Aerial Surveys Co. Among the 13,600 images in the collection are those from 135 golf courses up and down the east coast, from Massachusetts to Florida. A member of the British Royal Air Force during WWI, he usually flew between 1,000 to 4,000 feet which provided a great perspective from which to view course routings, bunker shapes and vegetation. Golf architect William Flynn often flew with Mr. Dallin in order to get a view of his routings from above. A west coast version of the Dallin collection exists in the Fairchild Aerial Photography Collection at Whittier College in CA. Between 1927 and 1965 roughly 500,000 images were taken by Fairchild Aerial Surveys Inc. These are mostly from the southwest and southern CA, but there are photos from every state except HI and DE. In the past few years, the collection has seen a shift in use from primarily engineers, environmentalists and geologists to researchers looking into golf course restoration. Another great source, which provides a somewhat more challenging research environment, is the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration located in College Park, MD. That houses the Cartographic and Architectural Records section and includes microfilm reels of photos taken between the mid-1930’s and the early 1950’s by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Department of Defense, then known as the War Department. The best aerial collection for identifying older golf course is that of the Soil Conservation Service, which indexed its photos by county and state. Probably the most notable improvement in historic golf research has been the decision by the U.S.G.A. to digitize a significant portion of its written archives, and this treasure trove of information now resides on a searchable database, known as the Seagle Electronic Golf Library.

Other sources exist, but are nowhere as well indexed as they are for example for traditional NPS resources. Golf courses on the NR are somewhat easier to identify, but are not indexed. The NPS’ Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation houses numerous original documents, and has yielded several connections between classic era architects and the Olmsted Brothers. A Google search for Wayne Stiles turned up the 1912 plan for Mount Hope, housed at Williams University. Geneology related websites and searchable databases may often allow a researcher to track down a descendant of the architect who may have old papers. Every now and then, a treasure trove emerges from the attic.

Conclusion

How do we address the situation of valuable historic golf landscapes being lost or altered when there is no framework, legal or otherwise to prevent this? Unfortunately, there is no simple answer. Among the private clubs, there may be little or no opportunity for a researcher to access the facility; for a public course, there may not be the funds to even address historic issues. The route through the National Register is also problematic.

I have only touched on the subject of historic documents, and this is a whole other area that merits attention. Many clubs have valuable historic records or plans stored improperly, or they don’t have any catalogue of what they have. This is not an unfamiliar situation from what we deal with at the NPS. Many of our valuable museum collections are years away from securing the funding to construct proper facilities for storage and display. Even some of the top private clubs with significant historic records are only recently addressing the subject of their collections.

Many golf clubs have prepared club histories, the majority commemorating a centennial, diamond or golden. Some focus in detail on the golf course as it has evolved over the years, others barely if at all, mention the original architect. Some are highly detailed accounts running hundreds of pages; others are done in house and barely scratch the surface. Again, golf courses don’t have the standardized requirements of documentation and preservation that units of the NPS are so fond of.

Hopefully through educating people at courses that have no appreciation or cognizance of what they have, we can help a few greens committee members at least start looking in the right direction. If nothing else, perhaps induce them to cobble together and protect important records and prepare brief histories of significant recreational landscapes that might otherwise remain undocumented.

Postscript

In the year and a half since this paper was originally presented, the welcome movement back towards designing courses in the classic style has seen a few more wonderful new entries such as the Gil Hanse designed Boston Golf Club and Eric Bergstol’s Bayonne Golf Club. Although they utilized far different methods to get there, both Boston and Bayonne emulate classic links style courses that require a good ground game and provide players both good and not so good, with options on almost every hole. There continues to be greater attention being paid to restore older courses. Courses designed just for walking have opened up in numerous places around the country and have been designed in what is often referred to as the minimalist style, essentially allowing the architect the freedom to find the course on the property. Along these lines, the team of Bill Coore and Ben Crenshaw have given us 21st century courses such as Bandon Trails and Friar’s Head on eastern Long Island and Tom Doak’s wonderful Pacific Dunes.

Two key components of building any great golf course have not changed: a great piece of property and no real economic constraints. Not to mention founders and architects with vision or simply someone looking to create “Dream Golf.” Naturally, the best courses coming along these days tend have no real estate component to them, other than a cabin or two for members and their guests. The older a course is in this country, the less likely it was to have had constraints imposed by adjoining properties or neighbors, but this may have changed.

Perhaps the best news for golfers favoring the classic style of play is that the only one of the aforementioned places where the public can play is adding a fourth course, and may one day may contain as many as seven. A fourth course at Bandon Dunes is currently being designed by Tom Doak and Jim Urbina, with input from many CB Macdonald afficainados including owner Michael Keiser, Geogre Bahto and Bradley Klein. This course will be called the Old Macdonald and will pay tribute, both in spirit and design to Charles Blair Macdonald.

From left to right: Brad Klein, Mike Iacono (Green Keeper at Pine Brook), author Kevin Mendik and Paul Jamrog (Green Keeper at Metacomet).

This paper was presented on May 6, 2005, the same day the Baltusrol Golf Club was formally listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

I am defining the Classic period from roughly the mid 1890’s to the mid 1930’s. Relatively few golf courses were constructed from the early 1930’s until a few years after the war, many had been neglected or abandoned during the interim, significant new techniques and equipment for construction had been developed during the war years and most importantly, the vast majority of pre World War II golf architects did not continue designing courses after the war. Golfweek Magazine annually publishes a well known list of The Top 100 Classic Golf Courses in America, but they consider the Classic Period to extend until 1960. In any case, their list is a ranking compiled from Raters who are asked to tour several of the courses each year and submit their ratings based on a ten part set of criteria. Therefore, it is essentially subjective. It is also interesting to note that one of the developers oehind Golfweeks’ Top 100 lists, George Peper, has essentially apologized for that creation. See Links Magazine May, 2006.

As of January 10, 2007. Personal communication with Kathy Kupper, NPS Office of the Director.

National Park Service Organic Act, signed into law on August 25, 1916 by President Woodrow Wilson. (39 stat. 535, 16 U.S.C. 1). In fact there are 22 Federal Laws that govern in some way the manner in which the NPS conducts planning, preservation, interpretation and public access to the units with the system.

See Smead, Susan E. and Wagener, Marc C., Assessing Golf Courses as Historic Resources. Cultural Resource Management No. 10, 2000, pp 16-21. CRM is an NPS publication.

There are currently 24 golf courses and or golf club houses listed on the NR.

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966. (Public Law 89-665, October 15, 1966; 16 U.S.C. 470 et seq.)

Norfolk Country Club Clubhouse, Norfolk, CT. Designated August 2, 1982. Taylor, Alfredo S.G. When the Newport Country Club, one of the five founding member clubs of the United States Golf Association, decided to undergo a substantial historic restoration and renovation of their clubhouse, the club did not seek listing on the National Register, nor are their plans to do so. The pre-1900 clubhouse was designed by Whitney Warren, who was among the architects of New York’s Grand Central Station.

The U.S. Open is often held on National Register sites. The 2004 Open was at Shinnecock Hills (designated September 29, 2000), 2003’s Open was at Olympia Fields (designated September 9, 2001), the 1994 Open was at the Oakmont CC (designated a Historic District on August 17, 1984, and subsequently designated a National Historic Landmark on June 30, 1987, one of only two such designations for golf courses, the other being Merion GC in PA, designated an NHL on April 27, 1992). Baltusrol GC in NJ was officially listed in the NR on May 6, 2005. See fn.1.

Cornish, Geoffrey. Eighteen Stakes On a Sunday Afternoon: A Chronicle of North American Golf Course Architecture. Grant Books, Worcestershire, UK (2002), p.35. ISBN 0-907186-43-2.

Subscription Agreement that founded NGLA (1904). Macdonald considered the best American courses then to be his own Chicago Golf Club, the Myopia Hunt Club designed by Harbert C. Leeds and the Walter Travis’ Garden City Golf Club.

Macdonald, Charles Blair, Scotland‘s Golf Reminiscences 1872-1927. Golf New York, London: Charles Scribner’s Sons (1928).

Hutchinson, Horace. Metropolitan Magazine (1910).

The author is currently researching a biography of Mr. Stiles along with co-author Bob Labbance. That book is expected to be published during 2007.

National Golf Links of America (NY), Chicago GC (IL), St. Louis CC (MO), Piping Rock Club (NY), Sleepy Hollow (NY), The Creek Club (NY), The Course at Yale (CT), The Mid Ocean Club (Bermuda) and Old White Course at The Greenbrier (WV), which is available to resort guests. However, the cost of staying at the resort makes access prohibitively expensive for most golfers.

.Bahto, George. The Evangelist of Golf, The Story of Charles Blair Macdonald. Chelsea, MI: Clock Tower Press, LLC (2002). ISBN I-886847-20-1

The Links Club, Rosilyn, NY.

Wexler, Daniel. The Missing Links America’s Greatest Lost Golf Courses & Holes. Chelsea, MI: Sleeping Bear Press, LLC (2000). ISBN I-886947-60-0

Doak, Tom et al. The Life and Work of Dr. Alister MacKenzie. Sleeping Bear Press, Chelsea, MI (2001). ISBN I-585360-1-8 See also, Bahto, above. See also, Tillinghast, Albert W., The Course Beautiful, A Collection of Original Articles and Photographs on Golf Course Design, ed. Richard C. Wolffe Jr., Robert S. Trebus and Stuart F. Wolffe Lynchburg, VA: Progress Printing (1995). Copyright Treewolf Productions. ISBN 0-965181-80-4, Tillinghast, Albert W., Reminiscences of the Links, A Treasury of Essays and Vintage Photographs on Scottish Design and Early American Golf, ed. Richard C. Wolffe Jr., Robert S. Trebus and Stuart F. Wolffe Rockville, MD: Smith Lithograph Corporation (1998). Copyright Treewolf Productions. ISBN 0-965181-81-2, Tillinghast, Albert W., Gleanings From the Wayside, My Recollections as a Golf Architect, ed. Richard C. Wolffe, Jr., Robert S. Trebus and Stuart F. Wolffe Rockville, MD: Smith Lithographic Corporation (2001). Copyright Treewolf Productions. ISBN 0-965181-82-0. See also, Van Liew, Bill. 2001. Tillinghast & Berkshire Hills. Commonwealth Golf Annual Magazine. 56-59, and Mendik, Kevin. 2003. Playing With Hickories: The Mid Ocean Club. Golf Collector’s Society Bulletin, 156 (October).

See Macdonald, Scotland‘s Gift Golf Reminiscences.. Ross, Donald. Golf Has Never Failed Me: The Lost Commentaries of Legendary Golf Course Architect Donald J. Ross. Farmington Hills, MI: Clock Tower Press, LLC (1996). ISBN I-886947-10-4. MacKenzie, Dr. Alister. The Spirit of Saint Andrews. Bantam Doubleday Dell (1998). ISBN O-767901-6-9. Dr. MacKenzie’s book was written in 1933, but was not published until over 50 years later.

The Donald Ross Society was founded in 1989, and can be found at www.donaldrosssociety.org.

Anecdotal evidence includes a story that in the 1970’s when Pinehurst was taken over by a new corporation, they literally threw out the 10,000 or so photographs taken over the decades at Pinehurst, and these were rescued from the dump by a secretary who retained them for years until turning them over to the Donald Ross Society.

The Tillinghast Associations was founded in 1998, and can be found at www.tillinghast.net.

Cornish at p. 45.

Labbance, Bob. The Old Man The Biography of Walter J. Travis Sleeping Bear Press, Chelsea, MI (2000) ISBN 1-886947-91-0.

The Walter Travis Society was founded in 1994, and can be found at www.buff-golf.com/travis.htm.

Fergesun, Charles B. and Raffery, Pierce. The Fishers Island Club and its Golf Links” The First Seventy-Five Years 1926-2001. Second Edition. Published by the Fishers Island Club, Inc. Fishers Island, NY (2002). ISBN 0-972195-0-X. The First Edition Sixty-Seven Years of the Fishers Island Club Golf Links was published in 1994.

Mackay, Robert B., Baker, Anthony K., and Traynor, Carol A. Long Island Country Houses and Their Architects: 1860-1940. New York, London: Society for the Preservation of Long Island Antiquities in Association with W.W. Norton & Company (1997). ISBN O-393038-56-4. Mr. Macdonald commissioned both Annette Hoyt Flanders for the 1923 Landscape Plan and Rose Standish Nichols for the Formal Gardens at Ballyshear, which overlooks NGLA. Another of his homes overlooks the Chicago GC.

Cornish, pp. 45-46. See also Peper, George, et al. Golf in America The First One Hundred Years. Henry N. Abrams, Publishers, New York. (1988). p. 281. ISBN 0-8109-1032-2 For information generally, see the website of the Golf Course Superintendents Association of America at www.gcsaa.org.

A great example of this is the growth over many decades and recent removal of privet hedges behind the green and around the No. 7 tee at Shinnecock, which proved to be the most challenging hole at the 2004 U.S. Open. Eight foot high privet hedges had surrounded the tee on three sides, thus sheltering the player from the wind. In addition, a large row of trees had also been removed from behind the green, which had blocked the wind on the green.

Personal conversation with Rick Wolffe, President, The Tillinghast Association, Historian, Baltusrol GC. July 24, 2001.

Tillinghast, The Course Beautifu at page 54. See also, Travis, Walter J; Practical Golf, New York: Harper & Brothers Publishing, 1900, 1902 & 1909 editions.

Labbance, Bob and White, Patrick, The History of the Springhaven Club 1896-2004, Montpelier, Vermont: Notown Communications 2004. ISBN 0-9752856-1-0.

During the 1920’s significant advances in turf grass science and management were occurring. In 1920, the USGA formed the “Green Section.” The National Greenkeepers Association was formed in 1926 (now known as the GCSAA).

Labbance, Bob and Whitteven, Gordon. Keepers of the Green A History of Golf Course Management. Sleeping Bear Press Chelsea, MI (2002). ISBN 1-575041-64-2.

Jennings, Jonathan CGCS. Prairie Fire! Using fire to improve the condition of unmown rough areas. USGS Green Section Record. Jan/Feb 2004.

Curtiss, Frederic H. and Heard, John. The Country Club 1882-1932 Privately Printed, Brookline, MA 1932. Plate IV, p.74.

Caner, George C. Jr. History of the Essex County Club 1893-1993. Essex County Club, Manchester-by-the-Sea, MA (1995). ISBN 0-964177-70-6. Phil Wogan’s drawing at page 38 was prepared from an 1895 course description. The first actual drawing of the 1895 layout of the Chicago GC was done by hand by a member when he joined in 1898.

Weeks, Edward. Myopia A Centennial Chronicle 1875-1975. Hamilton, MA (1975), at p. 33.

Weeks, at p. 34 & p.53.

Cornish, 18 Stakes at p. 36-37.

See Cornish, Geoffrey, The Architects of Golf: A Survey of Golf Course Design From Its Beginnings to the Present, With an Encyclopedic Listing of Golf Architects and Their Courses. Harper Information (1993) at p. 322. ISBN 0-062700-82-0

Boston Globe. September 25, 1904 at p.4.

Golf. U.S.G.A. Official Bulletin, June, 1904 section entitled “Through the Green,” at page 401.

Caner, at p. 39.

Caner, at p. 39.

Cornish, Architects at p. 206.

Caner, at p. 89

Caner at p. 92.

As of this writing, the author and Bob Labbance have traced Mr. Stiles’ work to 77 courses.

Personal conversation with Geoffrey Cornish, living Golf Architect who worked with Wayne Stiles. November 3, 2003, Amherst, MA.

The others are The Country Club in Brookline, MA, The Newport CC in RI, Saint Andrews GC in Yonkers, NY and Shinnecock Hills in Southampton, NY.

Bradley Klein, a Senior Writer for Golfweek refers to the Chicago GC as “Seth Raynor’s design masterpiece” in the April 30, 2005 issue. Another perspective is that as Mr. Macdonald was very much on the scene at Chicago before, during and after Raynor’s work, there is little chance Raynor would have made alterations to the course without Macdonald’s approval and guidance.

The latest new course prior to WWII is arguably Mink Meadows on Martha’s Vinyard, MA, completed by Wayne Stiles in 1936. Augusta National was completed in 1933. After the war, a new generation of architects emerged, and along with advances in mechanized construction, golf design was never the same.

At the Hartford GC in CT, which dates back to 1896, the name, location and layout have been altered, by at least 7 architects and numerous superintendents, including an unknown designer of the original nine, superintendent Wilson around 1900, Alexander Findlay in 1909, Donald Ross from 1914-1917, Devereaux Emmet from 1921-1924, another unknown architect or superintendent in the 1930’s based on aerial photos, Donald Ross again in 1946 involving a relocation and addition of 9 more holes, Orrin Smith completing Ross’ worked after Ross’ death in 1948, but did not stick to Ross’s plans, William and David Gordon in 1965 and 1969, Geoffrey Cornish remodeled several greens in the early 1970’s and Al Zikorus rebuilt all the greens on the third nine from 1979-1981. Still not done, the club embarked on additional work in 1991 that was done essentially in house, which included bunkers never constructed from the 1946 Ross plan, redesigning of 5 greens and remodeling most of the existing bunkers. See, Pioppi, Anthony. Hartford’s Heritage, Connecticut Golf Magazine, Volume IV, 2002. PP 58-65.

Hartford Golf Club Historic District, listed June 26, 1986.

Shinnecock Hills Golf Club, listed September 29, 2000. Shinnecock Hills was founded in 1891 by William Vanderbuilt and Edward Mead (Not the William R. Mead of McKim, Mead and White) They brought Willie Davis from Scotland to design the original 12 hole course. He created a 9-hole women’s course in 1893. The 12-hole course was expanded to 18 in 1895 and the following year hosted both the U.S. Amateur and U.S. Open. Numerous smaller alterations occurred during the next 20 years. By 1916, the layout was not only outdated based on equipment and architecture, but thoroughly overshadowed by CBM’s adjacent masterpiece, the NGLA. Their clubhouses are visible from each other. CBM was retained to design a new 18-hole course and that layout remained until 1930 when New York State extended Route 27 (the area’s primary east-west corridor even today) practically bisecting the course. A 1938 aerial photo from the National Archives shows three of the CBM holes still visible southeast of the road. (Source, Missing Links, p. 101) William Flynn designed the new layout using additional land on which 10 of toady’s holes lie. The only remaining CBM holes are 3 and 7 today, originally 13 and 14 respectively. See also Goodner, Ross. The 75 Year History of Shinnecock Hills Golf Club. Shinnecock Hills Golf Club, Southampton, NY (1966). Shinnecock’s clubhouse was the first designed exclusively for a golf club. Sanford White, 1892.

Labbance, Bob. The Centennial History of the Woodstock Country Club. New England Golf Specialists, Stockbridge, VT (1995). Alexander Findlay layouts date to 1898 and 1900, William Tucker’s designs from 1905 and 1912, Wayne Stiles’ 18-hole layout existed from 1925 until Robert Trent Jones’ early 1960’s layout. The existing 5th hole is the only surviving Classic Period hole.

The CC of Barre, VT is well documented as a Wayne Stiles course, but which holes exactly, is uncertain. Personal conversation with Bob Labbance, September 17, 2004. Bob Labbance has only recently (Fall of 2006) determined, through interviews with former superintendents and club professionals, which holes can be accurately attributed to Mr. Stiles. Personal conversation with Bob Labbance, December 20, 2006.

A recent example is the TPC of Boston, which since 2003, has hosted the Deutsche Bank Championship. The course, which opened in 2002, has been reworked considerably each year after the tournament.

At the Course At Yale, almost Ã…¸ of the area cleared was ledge and swamp. 20,200 Sticks of dynamite were used, almost a mile and a half of holes were drilled, and roughly 16,000 cubic yards of muck were dredged from the swamps and used to cover the greens. Seven miles of pipe were laid for the pumping and drainage system. Report of the Yale Golf Committee to The Board of Control. February 22, 1926. See also, Cornish, pp. 45-46.

Formally opened on June 5, 2005, Bandon Trails, the third course at Bandon Dunes in Oregon, contains a Biarritz green on the fifth hole. The architects, Ben Crenshaw and Bill Coore used over 800 acres to route the new course, and found many of the holes in the landscape. Their use of heavy equipment was minimized in shaping the holes, but was essential in order to build the course in a timely and economic fashion.

In January of 2004, the USGA adopted a new rule limiting the Spring-Like Effect of Drivers. Most recently, on April 11, 2005, the USGA sent a letter to numerous golf ball manufacturers asking them to consider designing and manufacturing experimental balls that would reduce their maximum distance by 15 to 25 yards in order to comply with a hypothetical set of rules being researched together by the USGA and the Royal & Ancient Golf Club of St. Andrews. See also, Golfweek April 23, 2005. pp. 4, 25, 26, 39 and 40.

McGimpsey, Kevin W. The Story of the Golf Ball. Philip Wilson Publishers, Ltd, London (2003). ISBN 0-85667-558-1

Ellis, Jeffrey B. The Golf Club 400 Years of the Good, the Beautiful & the Creative. Zepher Productions, Inc. Oak Harbor, WA (2003). ISBN 0-9653039-2-6

The feather stuffed golf ball or Feathery was in use from the game’s origins in the 1400’s through the 1880’s, when the Gutta Percha ball (introduced in 1846 and known as the Gutty) replaced the feathery. The Gutty was then replaced by the rubber-cored or Haskell ball (introduced in 1898, and patented in 1899). The rubber cored ball (known as the three-piece with center, windings and cover) has since given way to the solid core or two piece ball. The cover has gone from animal skins to the gutty to the balata around 1905 to the modern Surlyn cover, introduced in the early 1970’s. As for clubs, the widespread use of steel shafts in the late 1920’s and early 1930’s essentially replaced the hickory shaft. The persimmon head for drivers was used primarily from 1950 to 1970. The use of graphite shafts became widespread in the mid 1980’s, which were introduced in 1970. The introduction of the titanium driver in 1995 is the latest innovation.

Thomas, George C. Jr., Golf Architecture in America Its Strategy and Construction. The Times-Mirror Press, Los Angeles, CA (1927). See Forward and p. 287.

Labbance, Bob. A Return to Glory Historical Greens Make a Comeback .Superintendent May, 2005 pp. 9-13.

See Curtiss at p. 77. The first 18 had been laid out in late 1899, after several 9-hole layouts over the club’s first few years of golfing.

Mackenzie, Alister. The Spirit of St. Andrews. Sleeping Bear Press, Chelsea, MI (1995). Mackenzie’s work at Augusta National was completed in 1932. See fn 82.

Peper, George, writing in Links Magazine, April 2006 at p. 20.

The author is a member of the Grounds & Greens Committee at Pine Brook CC (Wayne Stiles 1924). He joined the Committee after much of the bunker work had been completed, and continues to work to avoid similar endeavors.

Mr. Ron Prichard has restored such courses as Pinehurst #2 (Site of the 2005 U.S. Open), Aronimink CC (site of the 2005 U.S. Senior Open), Charles River CC, Blue Hill CC and The Orchards (site of the 2004 U.S. Woman’s Open) in MA, Point Judith CC and Wannamoisett CC in RI, among others. Others include Ron Forse, Tom Doak and Gil Hanse.

The Woodlands GC in Newton, MA is a good example. Founded in 1896, the course is now bisected by the Boston light rail system, is bordered on one side by 8 lane Route 128, on another by 4 lane Route 16, the entrance is directly across from a several hundred spot parking garage, apartment complex and a regional hospital, and another side has a major road that leads to an even larger light rail parking lot. The Hyde Park municipal courses at Niagara Falls suffered through Robert Moses’ routing of two bus size tunnels underneath the courses in the early 1950’s to accommodate features of the NYPA hydro facility at Niagara Falls, the largest east of the Mississippi. Even the Redan hole at the Chicago GC has suffered from a 2004 home development that places a house literally 50 yards from the green site, considered by many to be sacred ground. From the author’s perspective, this is the functional equivalent to placing a cell tower in or immediately adjacent to a National Historical Park. Unfortunately, this threat has become widespread.

Others include Webhannet GC in Kennebunk, ME, and Bellevue CC in MA.

M.G.L. Chapter 131, Section 40, 310 C.M.R. 10.00.

A Notice of Intent pursuant to the MWPA to complete that work was filed with the Canton Conservation Commission in the spring of 2005 and its outcome is uncertain. As of this writing, the 8th green on the Challenger course remains untouched. This situation would be comparable to the NPS restoring all but one room of a historic structure.

The author was a member of Blue Hill, and consulted on the wetlands compliance aspects of the project during the summer of 2001. The author resigned from the club at the end of 2006.

ee Klein, Bradley and Boslet, Michael A. Raiders of a Lost Art, Golfweek, March 5, 2005. See also, Labbance. Superintendent, May 05.

www.whittier.edu/fairchild/home.html

Craig Disher’s email address is cdisher@verizon.net.

www.usga.org/aboutus/museum/library/segl.html

Examples in the northeast include the New England Historic Geneological Society at www.nehgs.org and www.ancestry.org.

A great example of this is The Spirit of St. Andrews, written by Dr. Mackenzie in 1933, never published and subsequently uncovered 60 years later by Raynond Haddock whose father Tony Haddock, was Dr. Mackenzie’s stepson.

Go to www.cr.nps.gov/nr/listing.htm for procedure and forms.

In the context of researching Wayne Stiles, the original 18 hole plan for the course dating to 1936 was located in the then club President’s basement. It had been folded and mice had gotten to it. Remarkably, the mice had only chewed areas with no text or drawings. The plan, partially restored and under museum quality plexiglass, now resides in the clubhouse on Martha’s Vineyard.

The St. Andrews Golf Club in Yonkers, NY, the oldest continually operating golf club in the country and one of the five founding members clubs of the USGA, hired a curator in 2000 in conjunction with their clubhouse restoration. He has catalogued the club’s several hundred artifacts, which include trophies, medals, photographs, clubs and other ephemera, and has been through several thousand books and papers. Original meeting minutes from 1894 that are relevant to the USGA’s formation have been uncovered, but according to Mr. Brian Siplo, their Curator, the “work will probably never be completed.” A similar effort is also underway at the Newport CC, where they restored and renovated the clubhouse in preparation for hosting the 2006 U.S. Women’s Open. The club is in the process of cataloging their historic materials., but has no intention of seeking NR status for either the clubhouse or golf course.

See Caner, above and Rawson, Chris. Where the Stone Walls Meet the Sea: Sakonnet Golf Club 1899-1999. Sakonnet Books, (1999).

Goodwin, Stephen. Dream Golf The Making Of Bandon Dunes. Algonquin Books, Chapel Hill, N.C. (2006).

The End