GlidingPast Fuji – C.H. Alison in Japan

by

Thomas MacWood

“Gliding past Fuji, still snow-capped, the luxurious Asama Maru passes accurately among a thousand sampans and comes to a rest alongside a modern quay.”

This is how golf architect CH Alison described his entrance into Tokyo Bay. A disciple of a movement in golf design that began outside London and spread through the Western world, Alison was the first and only golf architect of that sect to set foot in Asia. Invited to Japan in 1930, he brought a philosophy of architecture born on the natural links and melded it perfectly with the Japanese aesthetic to produce an enduring legacy. The impact of his short visit was so forceful that seventy years later it remains the dominant influence on design in that golf crazed nation. But Hugh Alison was not the first visitor to have an altering effect on Japan.

The Setting

In the 17th Century Japan was involved in a trading network that included Europe and her neighbors China and Korea. The Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch and English all established themselves in the Far East and with them came Christianity.

At this time Japan was controlled by a form of centralized feudalism, divided into smaller fiefdom ruled by warlords and their samurai. These warlords congregated in the capital of Edo (Tokyo) advising the greater head of state – the Shogun. Fearing the effect of this foreign faith on homeland loyalties, the Japanese leadership cracked down.

By 1616 all Roman Catholic priests were banned from Japan. The next step was a series of decrees to close the country from all foreign influence. The English left on their own accord, the Spanish and Portuguese were banished, and the Dutch stayed but were confined to a tiny artificial island in Nagasaki harbor. To ensure sakoku, or closed country, all Japanese were forbidden to travel abroad and those who did could never return on pain of death.

Only small domestic coastal ships were permitted in Japan’s waters, unauthorized ships were fired upon. Shipwrecked foreign sailors were to be “killed in the surf” before reaching dry land. Foreign books were illegal. For the next two centuries Japan was isolated from the world.

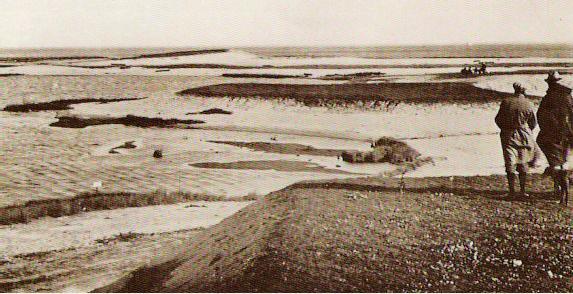

That would all change in 1853. A naval flotilla led by Commodore Mathew Perry attempted to enter Edo (Tokyo) Bay on July 2nd. The American warships were six to seven times the size of any ship in Japan and were equipped with considerable firepower, especially when matched against the antiquated Japanese arms. Japan had little choice and Perry was permitted to land. The Perry mission was to deliver a message: humane treatment for distressed foreign sailors and the right to provision in designated Japanese ports. It also suggested that commerce be established. This incident sparked the development of modern Japan.

Although Japan enjoyed significant cultural development through the ‘closed’ era, the country lagged behind technologically. To catch up quickly, Japan sought expertise from around the globe. The oyatoi (honorable employee) was brought to Japan to teach a cadre of applied arts and sciences. The military, medicine and the sciences looked toward Germany; the French taught legal systems; the British brought naval, textile and steel-making skills; America was the model for the educational system.

In addition, many Japanese sought education abroad at British and American universities. It was said the Japanese did not possess an original or inventive mind, but one must remember the modern nation of Japan was quite young, and the speed of their progress hardly gave the Japanese time for inventiveness, but there can be no dispute, the Japanese were brilliant imitators. As Japan expert William Williot Griffis wrote in 1933, “being eclectic, it may be said that the Japanese first adopt, then adapt, and finally become adept in most what they experiment upon.”

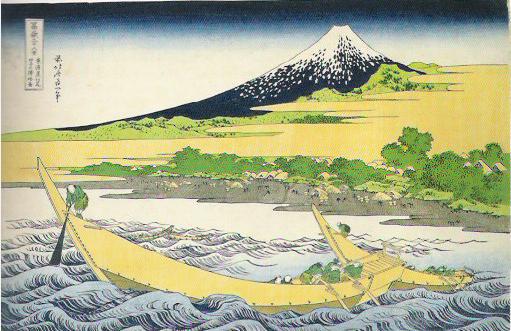

The assimilation was not solely found in Japan. Japanese art with its mysterious allure fascinated the Western world. In the late 19th Century the phenomenon of Japonisme was a major influence upon the arts and in particular on the Aesthetic movement. In Paris and London the American painter James Whistler created Japanesque compositions, as did Manet, Toulouse-Letrec, Gauguin and Van Gogh. In America one of the most important art educators and artists, Arthur Wesley Dow was inspired by the art of Japan. He was also a major proponent of the Arts and Crafts movement, with its similar philosophy of craft being on par with fine art.

In America, architects Frank Lloyd Wright and the Greene brothers exhibited a distinctive Japanese flair. After a tour of America, Charles Ashbee, the British Arts and Crafts leader wrote, “Greene’s work [is] among the best there is in the country. Like Lloyd Wright the spell of Japan is on him.”

Dawn of Golf

Back in Japan, the opening of worldwide commerce brought a number of foreign nationals who set down roots. One such man was an English tea merchant, Arthur Groom, who came to Japan in 1868, settling in Kobe and taking a Japanese bride. He enjoyed outdoor pursuits, especially mountaineering, exploring the wild beauty of the mountains above Kobe. With the summer heat stifling, Groom built a mountain bungalow on Mt.Rokko as a seasonal retreat. As the story goes Groom and his friends (over glasses of whisky) would lament the absence of golf in Japan and one summer evening decided to do something about it. There is no record of an actual designer (Groom is credited with pushing the project), but by 1902 there were 3 or 4 golf holes in play on Mt.Rokko. That increased to nine the next year and the Kobe Golf Club was born in 1903 with 120 members, mostly Scots and English. A second nine was added in 1904–the 4135 yard course of today is very much as it was a century ago. Ironically Groom did not play the game prior to constructing the golf course, he did father 16 children however, so perhaps time was an issue.

As word spread of the links at Rokko-san another group of foreigners developed a nine-hole course for the Yokohama Golf Club (1906). At this time there was a growing number of Japanese living abroad who had fallen for the game, and upon return to Japan there was no course available to them. One such man was Junosuke Inouye, ex-Governor of the Bank of Japan, who had picked the game up in New York. He was the major force behind the creation of the first golf club created by Japanese for Japanese — the Tokyo Golf Club in Komazawa opened in 1914. The course was designed by an American named Brady, the captain at Yokohama GC, and a Scot veteran named Colchester. This marked the true beginning of Japanese golf.

As the game’s popularity increased, there not only became a demand for more courses, but also better courses. Many Japanese had experience the game in Britain and America, and had an appreciation for the excellence of modern golf course design. They were not satisfied with simply being able to play the game on the primitive courses found in Japan. It was in the 1920’s that the quality of golf architecture slowly began to improve. Hodgaya was the first modern Japanese design-it was carried out by Walter Fovargue who had been involved with Lakeside in San Francisco, Annandale in Pasadena and Wawona Hotel at Yosemite. The Crane brothers of Kobe were fine golfers, born of English father and Japanese mother, they created the original short eighteen at Naruo in 1924. David Hood designed and built the fine course at Ibaraki (1925) and in 1926 the Tokyo GC was expanded from nine to eighteen.

Looking West

The Tokyo layout at Komazawa was described as “a delightful little course . . . very well trapped and bunkered.” Its location was convenient to the majority of members who worked in the city. Regrettably when the course was originally developed among the rice fields in 1913, the club made the decision to lease the land, but as the city of Tokyo developed and expanded, the Komazawa location became prime real-estate. The landholders forced the club to make a decision, either purchase the land or move. Unfortunately the price was exorbitant, plus the course was short with no room to expand. The decision was made to move.

At the time Hodogaya was considered the premier golf course in Japan. Although a solid design, it was far from perfect, being on hilly land it featured more than a few blind shots. The new breed of internationally savvy golfers wanted more, and one such man was Tokyo GC’s Komyo Otani. He had been exposed to the game as a student in England, and was among a group of Japanese who admired the heathland golf courses outside London. When the decision was made to move, Otani, along with a handful of like-minded members, considered it the perfect opportunity to build a course to rival the best from overseas. And who better to carry out the design, none other than the world’s premier golf architect – Harry Shapland Colt. His design portfolio was superb, including the heathland gems of Swinley Forest, St.Georges Hill, The Addington and Sunningdale-New; the redesign/modernization of the championship venues at Hoylake, Lytham, Muirfield and Sandwich; and a collaboration with George Crump on what was considered the world’s greatest golf course, Pine Valley. In 1929 Otani convinced the Club to approach Colt and surprisingly he agreed.

As part of his agreement Colt commanded a handsome fee of £1500 (…½ 17,500 at the pre-war exchange rate), as well as the cost of travel and living expenses while in Japan. Unfortunately Colt, now 61 years old, hadn’t traveled overseas since 1913 and the long voyage concerned him. Instead, he designated his partner CH Alison to make the trip and carryout the design. This news was not well received back in Tokyo. The club had already invested a great deal on the new site at Asaka (nearly …½1 million) and now was expected to pay a large fee for an unknown architect. Otani did not waiver. He along with his ally, club secretary Tashira Shiraisha, were convinced Alison was their man.

In a shrewd move Shiraisha called a directors’ meeting in August when most were away on holiday avoiding the summer heat in the mountains, and without opposition Alison’s invitation was easily approved. Otani would later rationalize, “I believed it was necessary, not only for the club, but also for the future of Japan’s golf world.”

Charles Hugh Alison was no golf design neophyte. Born in Lancashire, England in 1883, he had been educated at Malvern and Oxford. Better known for athletics than academics, Alison excelled at both cricket and golf. He was the youngest member of the Oxford and Cambridge Golf Society’s team, captained by John Low, which toured America in 1903. Following a short career in cricket and golf journalism, Alison became the secretary of the new Stoke Poges Golf Club in 1907, a Colt design in the London outskirts. It is believed he dabbled in design while serving as secretary, but he didn’t devote himself completely to golf architecture until after WWI – going into partnership with Colt and Alister MacKenzie. Almost immediately he was dispatched to America where he worked throughout the twenties, producing a number of impressive designs, including Kirtland, Fresh Meadow, Burning Tree, North Shore, Century, CC of Detroit, Timber Point, Sea Island and Milwaukee. With economic difficulties effecting American work, the Japanese project presented an exciting opportunity.

Japanese Exploits

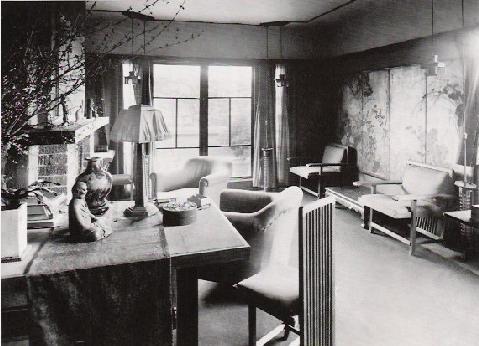

Hugh Alison arrived in Japan in early December 1930 aboard the luxury liner Asama Mura from California. He did not travel alone, bringing along one of his most trusted construction supervisors, George Penglase. Upon arrival in Yokohama Alison was taken to the Asaka site for the Tokyo GC, inspecting the 200 acres with Otani, Penglase and Rokura Akaboshi, a fine golfer who had been educated in the States. After studying the site, Alison, armed with contour maps, secluded himself in the Imperial Hotel (a Frank Lloyd Wright design) and after seven days emerged with detailed plans for the new course.

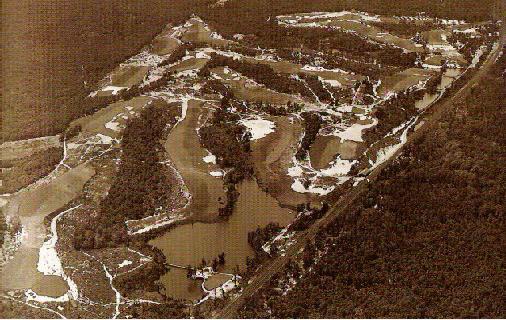

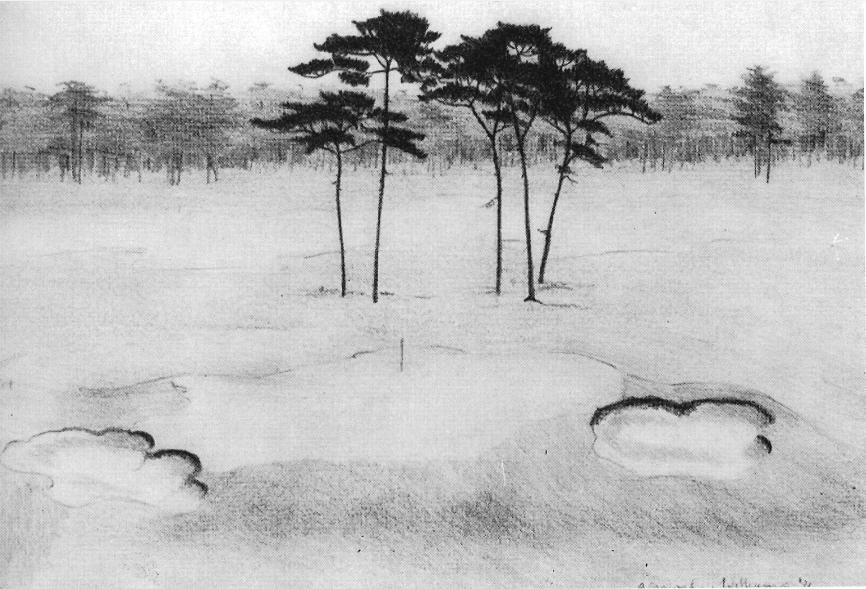

Alison described the terrain at Asaka as “land as flat as a pancake.” The tract comprised numerous small farms and was for the most part devoid of trees excepting a few large pines. However Alison was given creative freedom, a significant budget (Ã…½ 300,000) as well as an incredible army of laborers — 60,000 strong. He likely viewed the site, devoid of natural features, as a blank canvas to employ his creativity. “Money was not spared, and a picturesque lake, much planting, and many artificial undulations and bunkers have alleviated the deadness of the plain and have put some life into the golf. The wide and flat natural terrain naturally resulted in an excellent sequence of holes, in plenty of alternative lines of play, in the easiest walking imaginable, and in an attractive conjunction of the 9th and 18th greens under the windows of the Club House. Though it lacks the thrill of spectacular landscape set in wild surrounds, Asaka is a pleasant course to play and from the back tees is sufficiently exacting for the ambitious. It was very well constructed by Mr.George Penglase, whom I brought with me from the United States.”

Completed in May 1932 and measuring 6700 yards, the Tokyo Golf Club was the country’s first outstanding golf course – a landmark in Japanese golf architecture. Rokura Akaboshi remarked the Asaka course ” had a revolutionary impact on Japanese golf and will become a historic asset in the future.”

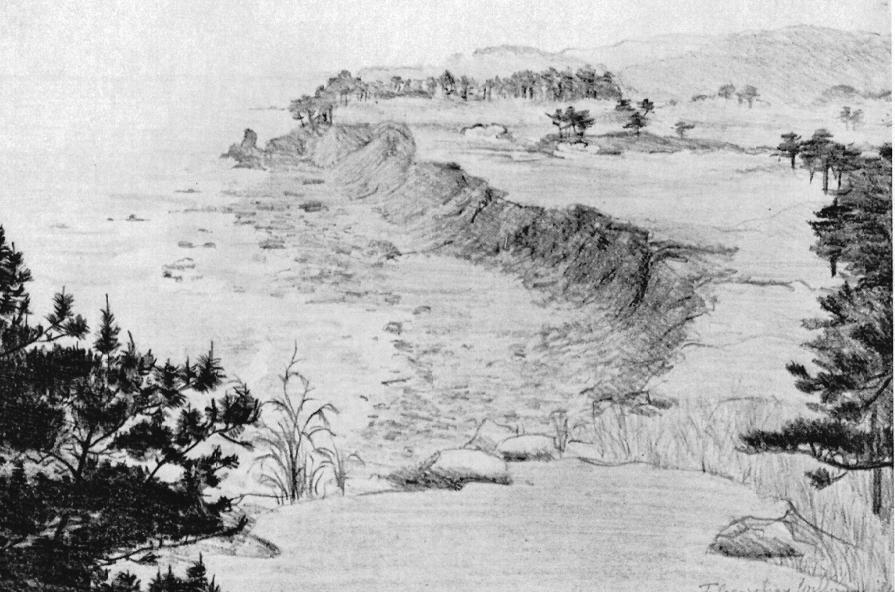

After the work had begun at Tokyo, Otani and Alison traveled to the retreat of Baron Kishichiro Okura at Kawana ostensibly for some R&R. The son of one of Japan’s most powerful and wealthy businessmen, Baron Okura was educated at Cambridge in the early 1900’s. After returning from Britain, Okura dreamt of creating a country estate in Japan like those he admired in the English countryside. He purchased 500 acres on the spectacular Izu Peninsula, built a rustic lodge and then asked Otani, his friend from his London days, to build a golf course. The Oshima course – named for a volcanic island just off the coast – was completed in 1928.

In describing the scene, it appears Japan was starting take hold of Alison, “This paradise is at least two hours from Yokohama, and much of the journey is along a narrow and earthquaked road, cut in the rocky coast. It lies among the hills beyond the hot springs of Ito, on a pine covered plateau bordered by red cliffs which descend down to a blue sea. From a wooded bay, a mile distant, a fishing village sends out boats with brown sails to complete the last detail of a perfect scene. At dawn the white mist gives way it the rising sun, and soon the branches of the pine trees are etched crisply against the light. And I, rising from the grid-iron which serves for bed, and refreshed with a beaker of soya-bean soup, set out to do my stuff.”

And so he did. Okura’s vision evolved from a woodsy retreat to a first-class golf resort and hotel, and certainly he had the experience, having built the Kyoto Hotel in Kyoto and Tokyo’s Imperial Hotel. Part of this new vision was a second golf course designed by Alison, “He [Baron Okura] contemplates the construction of a second eighteen-hole course, also on the edge of the sea, and anything which he undertakes is certain to be first class, the scenery resembles that of the French Riviera, but at not a single spot between the Italian and Spanish frontiers can found so superb a combination of sea, cliffs, trees and mountains . . . The course will be on rolling land, which provides an immense amount of variety, and will be quite first-class.” Several years later he would write, “The terrain itself is not mountainous, nor even unduly hilly, but it consists of rock. It was essential to place the fairways and greens in positions where there was soil, or where soil could be persuaded to stay: and at the same time to obtain enough visibility for the second shots. I sympathized with the constructors of this course. I have never heard the result of their labors, but conjecture that they overcame their difficulties and produced the most beautiful course in Japan.” After an initial delay, Alison’s Fuji course at Kawana was opened in 1936.

After returning to Tokyo Alison was asked by amateur golf architect Kinya Fujita to have a look at his newly constructed design for the Kasumigaseki GC. Fujita had picked up the game in the States as student (University of Chicago, Miami of Ohio and Columbia). After a period working in New York City for a silk importing firm, he returned to Tokyo to set up a new firm with American backing.

Fujita had been a member of the Tokyo GC and in 1928, when the club began looking for a new location, they had received an offer from Shohei Hocchi for the use of his land. Because it was considered too remote (30 miles away) the offer was refused. But Fujita and a number of Tokyo members decided to break away and developed Kasumigaseki independently. The design, under the guidance Fujita and Shiro Akaboshi (brother of Rokura Akaboshi) was ready for play in October of 1929. Following an inspection of the progress at Asaka – Alison, Fujita, Rokura Akaboshi and Penglase toured Kasumigaseki. Although he admired the course, describing it as “pleasantly undulating“, Alison made a number of suggestions, redesigning five holes – the 9th, 10th, 14th, 17th and 18th. The work was carried out by Penglase and completed in late February of 1931. Due to an overflow in membership, a West course (making the original course the East) was added in 1932, designed by Fujita and his assistant Seiichi Inoue. Inoue, inspired by the example of Alison and Penglase, would go on to become one of Japan’s most influential golf architects.

A blurry group photo at Kasumgaseki: K.Fujita, G.Penglase, S.Hottachi, CH.Alison and R.Akoboshi (left to right).

While on holiday at Kawana, Otani had introduced Alison to Seiichi Takahata a friend from the Tokyo GC. Takahata had been the head of the London branch of a Japanese trading company from 1912 to 1926. An avid golfer, he was a member of The Addington (designed by JF Abercromby in collaboration with Colt). In London, Takahata and Otani enjoyed numerous rounds together on the heathland gems. Takahata approached Alison in the Imperial Hotel, asking if he might assist him with a new project near Kobe — the Hirono Golf Club. Alison agreed to produce a basic routing for a fee of £500 (Ã…½ 6,000).

On the journey from Tokyo to Kobe, it appears Alison traveled with the brothers Akaboshi – Rokura and Shiro. Both fine amateurs they had perfected their games as students at Princeton and Penn respectively. Having been exposed to courses like Pine Valley, Pinehurst and Cypress Point, the Akoboshis were keen students of design and spent a great deal of time with Alison.

Before arriving in Kobe, Alison took a side trip in the beautiful city of Kyoto-famous for its gardens. Escorted by Sonyu Otani, younger brother of Komyo, he visited the enchanting gardens of Ryoan-ji, Shugakuin and Katsura. If the spell of Japan was upon him before Kyoto, undoubtedly it was after a visit to these tranquil sanctuaries.

Outside Kyoto lies the Ibaraki Country Club in “a delightful region of trees, hills and lakes.” After a round with the Akaboshis and Kinya Fujita, Alison was invited to make suggestions for alteration, which he did much to the Club’s satisfaction – redesigning 1, 6, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 and 17. “The valleys through which the course winds are somewhat narrow, but the scenery is delightful, and endless trouble has been taken to render the golf interesting and testing.” Following a tour of the ancient city of Nara, he was asked to inspect another existing golf course at the suggestion of Fujita. The Inagawa Golf Club lies between Kyoto and Kobe near Osaka – Alison submitted a redesign for this golf course as well. Now known as Naruo, the only holes he did not touch were the fourth and the tenth.

Onward to the seaport of Kobe and the Hirono project – by this time it was early January. Seiichi Takahata greeted Alison at the train station and the two men drove out to the proposed location twelve miles inland as the crow flies. The site was part of a large estate owned Viscount Kuki, a former feudal warlord and a keen golfer. What Alison found was a combination of “beautiful lakes and pretty ponds, natural valleys and ravines, good and gentle undulations all around, rivulets, mountains, hillocks and wood-lands, a real setting for an ideal golf course, all arranged by nature.” So much for the simple routing, the inspired Alison decided he would create a full blown design and the club was in total agreement – his fee was increased to £1500. After studying the land, Alison repeated his Tokyo method, retreating with notes and contour maps to the Oriental Hotel near the Kobe Train Station. After seven days he emerged with a design.

An artist’s interpretation of the 5th at Hirono.

The Hirono work was carried out by Chozo Ito under the supervision of Takahata. Ito is a somewhat mysterious figure. Japan’s first golf writer, he publishing Japan’s initial golf magazine in 1922. In 1925 he and Komyo Otani (of Tokyo GC) made a tour of the world’s great golf courses. In preparation for Hirono, Ito studied Penglase’s work at Tokyo and Kasumigaseki, incorporating many of his construction techniques. As Ito turned Alison’s plans into reality, he used photographs taken of bunkers, greens and other features encountered on his tour overseas. While constructing the course, Ito and Takahata were known to have heated exchanges about the depth and shape of bunkers – whoever prevailed, the results were spectacular. Hirono would open on June 19th, 1932.

Alison wrote, “Among Japanese courses Hirono is generally accepted as the best. It lies 20 miles form Kobe, the Liverpool of Japan, in an undulating country of wood and lakes. In 1930 wild boar were said to flourish there, but I am thankful to say that my acquaintance with them was made only at the dinner table. On 300 acres available for golf there was no human habitation, nor view of one…a map of the land was prepared by a Japanese surveyor showing the lakes and principal hills and dales. Not withstanding the trees and in places the dense undergrowth, this proved to be an excellent guide. The original layout was designed without undue difficulty, and few alterations were made after clearing was done.”

The par-3 7th at Hirono.

“Thanks to the energy of and enthusiasm of Mr.Takahata, Secretary of the Japan Golf Association, and to the placid perseverance of Mr.Chozo Ito, a long difficult course has been constructed here. Almost every hole has some bold natural feature, and the course will be a splendid test of golf.”

“For variety of scene and of strokes Hirono is difficult to beat. Whether for a blood match from the back tee, or for a gamble among the portly and venerable, I can name no superior among British inland courses. In America Pine Valley is more tightly bunkered and definitely more brutal, but Hirono comes up well to the first-class standard of the United States, and will afford much pleasant excitement, and perhaps a little pain, to players from that country.”

The tee shot at the par-4 14th Hirono.

After completing the design at Hirono , Alison returned to Tokyo in early February. He continued to survey the work at Asaka and Kasumigaseki, and advise Rokura Akaboshi on his own project Fujigaya and also Shiro Akaboshi’s design in progress, Fujisawa. By the end of the month, Alison left Japan and never returned – Penglase remained a little longer. During his three month visit Alison produced Hirono, Tokyo GC and the Fuji course at Kawana, undertook major alterations to Kasumigaseki-East, Ibaraki-Old and Naruo (Inagawa) and advised on Fujigaya and Fujisawa. That alone would have been a phenomenal legacy for a three-month stay. But the most impressive achievement of Alison’s visit was the impact he had upon so many individuals and their subsequent influence on Japanese golf.

The approach at the 14th at Hirono.

Aftermath

It is remarkable that Alison had any influence at all. While he toured Japan, the country was in the midst of a political upheaval, growing militarism and nationalism was inciting a growing anti-Western sentiment. Golf was looked upon as a British-American game, played by a privileged class and a huge waste of precious land. The media characterized golf as a bourgeois sport that would lead to the ruin of the nation.

In 1941 the military took over Tokyo GC and all of its facilities, completely destroying the landmark course which had only existed for nine years. Fujigaya and Fujisawa were also requisitioned and became casualties of war. Hirono was only slightly luckier – at the outbreak of the Pacific conflict it was converted into an agricultural plot, as were many of the Japan’s golf courses. Those few that remained were empty, except for a few diehards who played in secrecy. After the war the occupying forces took complete control of the nation, including all golf clubs. It wasn’t until 1952 that they returned any golf courses and facilities back to the respective clubs.

Alison left Japan in 1931 at the height of golf’s popularity – by 1952 the game had been dead for a decade. The enormous popularity that Alison helped to spark appeared to be totally extinguished. So how did Alison’s contribution live on? The answer lies with his disciples. Following the war these men would not allow Alison’s efforts to die.

Komyo Otani was the architect of the third Tokyo GC – strikingly similar to the Asaka. Otani would continue to act as a guiding force and is now referred to as the ‘Father of Japanese Golf’. Hirono was restored by Osamu Ueda, the man who assisted Ito in the original construction – he would go on to become one of Japan’s most active designers. Chozo Ito would leave a legacy of golf writing which included Alison as a key figure. Seiichi Takahata continued to act as an important golf official, promoting the game after the war. Akaboshi brothers left their Alison inspired designs of Sagami and Abiko. Kinya Fujita lent his architectural expertise during the reconstruction period and became the patriarch of Kasumigaseki. And Seiichi Inoue chose golf architect as his career after observing Alison at Tokyo and Kasumigaseki, assisting Fujita before going out on his own. He would become Japan’s most prominent golf architect and has been called the “Harry Colt of Japan.”

There were fewer than 100 golf courses at the outbreak of the Pacific war – today there are more than 2300. Although it is not necessarily the best measurement of architectural excellence, a look at the countries top 15 courses as rated by a panel of experts is enlightening. Hirono tops the list and is among eleven courses that are the work of either Alison (Hirono, Kasumigaseki, Kawana and Ibaraki-Old), Otani (Tokyo and Nagoya), Ueda (Koga), Akaboshi (Abiko), Inoue (Takanodai and Ibaraki-West) and Fujita (Kasumigaseki and Oarai). Not included is Alison’s redesign of Naruo which can found in an American magazine’s top 100 in the world.

The 7th at Kawana-illustrates Alison’s typical treatment of green and bunker design.

Alison’s Approach

When describing Alison’s design philosophy much has been written about his use of deep bunkers – known in Japan as ‘Alisons’. While there is no question they were an integral feature, far too much emphasis placed upon them at the expense of his equally important attributes, to the point where they have become almost a cliche.

In studying how Alison’s design style evolved it is interesting to note his own influences. Alison had the unique advantage of observing the revolutionary heathland architects, like Park-Jr., Colt and Fowler, as well as experiencing the grand decade of the twenties in the United States. He was able to see the work of North American contemporaries Ross, Tillinghast, Flynn, Raynor and Thompson (who constructed his York Downs design) first hand. Not only was he intimately familiar with famous seaside links in Britain, but also the American landmark courses of the National Golf Links of America, Garden City, Lido, Myopia Hunt and Pine Valley (where he advised). And we know he made at least one visit to California prior to embarking for Japan. It is possible, if not probable, he took this opportunity to see the spectacular designs at Pebble Beach, Cypress Point and Pasatiempo, and perhaps visit his old friend and design colleague Alister MacKenzie – an interesting conjecture.

The par-3 5th at Hirono.

All these influences contributed to the Alison style, a style that did feature very deep bunkers. Not only were his bunkers deep – both greenside and fairway – they were also very large in scale. Alison’s greenside bunkers were frequently as large as the greens they guarded. He often elevated the green well above the approaching fairway or tee, bunkers were then cut well below the elevation, in effect increasing their depth. Fairway bunkers were placed against or below mounding, also increasing their effective depth. And he was not opposed to an occasional forced carry — usually with bunkers set at a diagonal, allowing for choice and rewarding the bold play.

Greenside mounds would often encroach upon the putting surfaces. This was Alison’s preferred method of creating undulations in his greens, extending and merging either natural undulations or mounds on to the green surfaces. And like many designers his greens were oriented to one side or the other through the placement of greenside hazards or pronounced contours, rewarding those who chose the best angle of attack (occasionally the center was the preferred approach). Another common device was the tilting of his greens sideways — an approach from the wrong angle or one poorly struck would fall away.

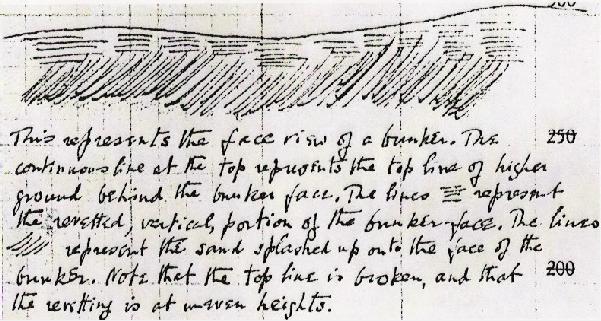

Alison’s sketch and notes guiding the proper construction of a bunker.

Alison wrote very detailed descriptions of how his design features should appear. His mounding was to have a ‘broken horizon’, and his bunkers were to have the sand ‘splashed’ up to point where it met a band native soil and the grass of the mound. He referred to this meeting of sand and grass as ‘rivetting’ – although he did not use the term in its classic sense – and it was to have an uneven outline. (Many of his bunkers in the US now have grass facing, with little or no flashing and are very regular in outline) In his construction notes he constantly uses the term ‘irregularizing’ — a clear acknowledgment of the irregularity found in nature. Although Alison often created features that were clearly artificial there is something aesthetically pleasing about them; he had a gift for creating man-made features that sympathized with the natural.

He was among the first architects to embrace the use of water in his designs–perhaps the influence of Pine Valley. This is somewhat of a paradox, throughout his career Alison wrote that water was a bad feature, or at least the excessive use of water was bad. “Water is a bad feature in that the ball cannot be played from it, and in consequence it does not test the golfer’s skill. Its hideous charm lies in the fact that it is inexorable, and its landscape effect is often very valuable.” In regards to Japan he observed, “The Japanese love of ponds and lakes, and their exquisite skill in making them, is known throughout the world. Their love of water-hazards, were it not for their self-control, might develop dangerously.”

Kirtland, Sea Island, Colony, Timber Point, Milwaukee, Tokyo, Hirono and number of other courses utilized rivers, streams, ponds and marshlands as integral design features — almost always oriented at an angle allowing for choice.

The diagonal use of water at Sea Island.

Taking full advantage of all natural undulations and hazards was the cornerstone of his design philosophy — while at the same time considering the “possibility of artificial work at the back of his mind all the time.” Unlike his mentor Colt, Alison wouldn’t likely be associated with the minimalist approach. He did not hesitate to move dirt in an effort to bring interest to an otherwise dull property – as he did at Tokyo. Many of his greens were artificially elevated or pushed-up, although this is sometimes difficult to detect due to his skill in melding them to their surrounds. At Timber Point and Sea Island he utilized the suction-dredge (first used at Lido) to transform flat marshy land into low lying dunes – establishing golf on land that was thought totally unsuitable. He used a similar method at Colony CC near Detroit, creating fairways and greens within St. John’s Marsh.

The Legacy

All of Alison’s design tendencies undoubtedly had a profound effect on Japanese golf architecture, but perhaps his most important contribution involved his recognition of the craftsmanship and aesthetics of Japan. That recognition can be detected in his writing. “On the farm land of the north we lunched once or twice in a cottage. Typically Japanese, it was built of planks grooved together and stained dark brown to blend with the setting. The tiled roof was dark brown also, with projecting up-turned eaves. The doors and windows slid open on grooves, and so perfect was the seasoned wood that the pressure of single finger opened either. Shoes were discarded in the porch, and the guests after bowing three times to their host, took their seats on the floor, which was covered with a thin mat woven of bamboo leaves. The window panes were paper, but the windows were left open unless the wind was cold.”

The sense of rhythm and harmony, simplicity of vision, the importance of design, that Nature should be the source of inspiration, these are the element found in the arts of Japan. Alison recognized these principals and merged his naturalistic tendencies of golf design born on the heathlands with that Japanese aesthetic. It was Alison’s ability embrace and incorporate what he saw in Japan that made his lasting influence possible.

What influence then did Japan have on Alison’s future designs? Did the spell of Japan affect his subsequent designs, as it had with Wright and Van Gogh? Unfortunately it is doubtful he was ever given the chance to implement any influence. After returning to Britain he was faced with worldwide depression and very little work, which was followed by World War and no work. He did submit a design for Huntingdale in Melbourne, but that was entirely a paper job without ever setting foot in Australia and one wonders if those charged with implementation shared his vision. After the war he took his design talents to South Africa and perhaps that is where you will find the Japanese influence, but my guess is those designs reflect an African touch. Ironically Alison, who spent the last six years of his life in southern Africa, died in 1952, the same year as the rebirth of golf in Japan.

So we must be satisfied with his impact on Japan and wonder what might have been. At least he left his words and impressions, in this final example we find his description of a Japanese rock garden that is eerily prophetic:

“The idea of repose finds its ultimate expression in the stone garden called Toranoko Watashi, designed by Soami. This is a flat rectangle of sand, perhaps as large as two lawn-tennis courts, bordered on two sides by the temple Ryoan-ji and on the other two by mud walls protected by a small roof of tile. On the sand rest ten rocks, the largest the size of a buffalo and smallest as big as a cat. While composing this masterpiece, Soami is believed to have lived at the expense of the abbot, and he took some years to place his field. We can imagine that in his annual spasm of creative ardour he would edge the buffalo a foot to the west and would drag the cat 26 inches to the north-east: having considered the result he would replace the cat, rake the sand, and sink into a state deep contemplation hardly distinguished from sleep. Let us not seek to probe into the mystery of the creative process: rather, let us rejoice in that which the artist has given us. His honourable product is inflammable and his will endure for ever.”

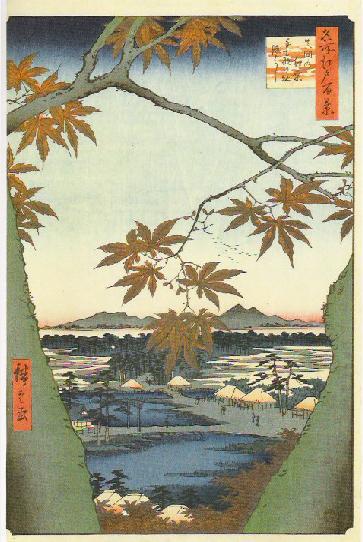

Maple Trees at Mama, Utagawa Hiroshige, 1830.

The End