Deconstructing Width

by

Joe Sponcia

May 2015

Club golfers are a sanctimonious bunch. Wearing one’s course rating and/or Championship tee length like a badge of honor reminds me of my Father telling me how strong I would be if I choked down a few brussel sprouts before being excused from the dinner table.

I am not sure where the false axiom of “Width is easy, narrow is good” began, but its after effects have been damaging to the enjoyment of the game for some time.

As courses have lengthened due to unfettered technology, part of the disappearance of width from the course design landscape can be directly attributed to increased length and the cost to maintain what was formerly less turf. Golf courses that used be a comfortable 6,500-6,800 yards from the Championship tees are now 500-800 yards longer…and like a piece of stretched taffy, width is often the sacrificial lamb.

Thankfully, the tide is turning for many clubs as width is now “in”, and narrow is becoming outdated.

Unfortunately, when the neophyte student of golf architecture, young or old, hears ‘wider’, he almost always cringes and says, ‘it will make the course too easy’. Width simply creates options for the more accomplished player and allows a fighting chance for the higher handicap to enjoy his day.

What challenge is there in hitting a fifty yard fairway, some might ask? For the bogey golfer (the average male handicap in the United States is 16.1) aimed at the center of the fairway with perfect path, but a 1.5 degree open club face – physics say he will miss his intended line by some twenty-four yards(!).

Noted architect Jeff Brauer has found the average PGA tour stop to have fairway widths in the 30-32 yard range, with major championships being trimmed to an anemic 26-28 yards. Typical private and public courses fare a bit better at 35 to 45 yards wide, according to Brauer.

To understand the importance of width and why it is such a critical piece of the architectural puzzle, one must first understand how architects like Donald Ross and Alister MacKenzie designed individual holes from the outset. For the most part, the golden age architects believed in options from both the tee box and the fairway. There was undoubtedly a safe side and a preferred side to play from. The safe side demanded some challenge, but was rarely considered overbearing for the bogey golfer. The preferred side was fraught with risk (a bunker complex, water feature, a hill or mound that had to be carried, or rough), but if the player could successfully navigate his drive, the reward was a less taxing second shot. The goal was playability for the high handicap, thought provoking to the scratch player.

Bobby Jones spoke of the philosophy at Augusta National in this way, “The course is not intended so much to punish the severely wayward shot as to reward adequately the stroke played with skill – and judgement”. Jones further stressed his goal to, “reward the good shot by making the second simpler in proportion to the excellence of the first”.

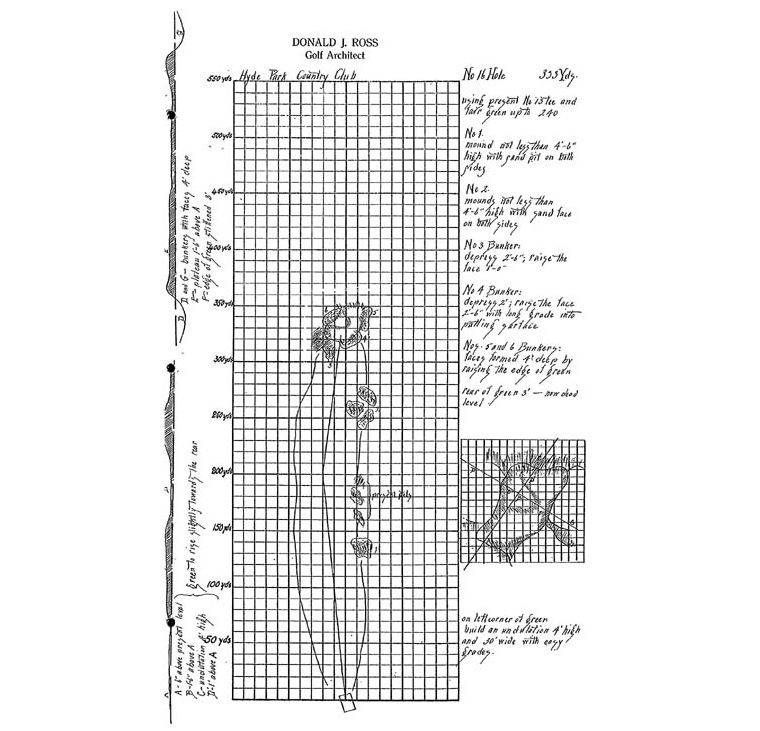

Original hole sketch, Hyde Park Country Club, 1920, Donald Ross – Par 4, 16th hole. (Courtesy Hyde Park Country Club).

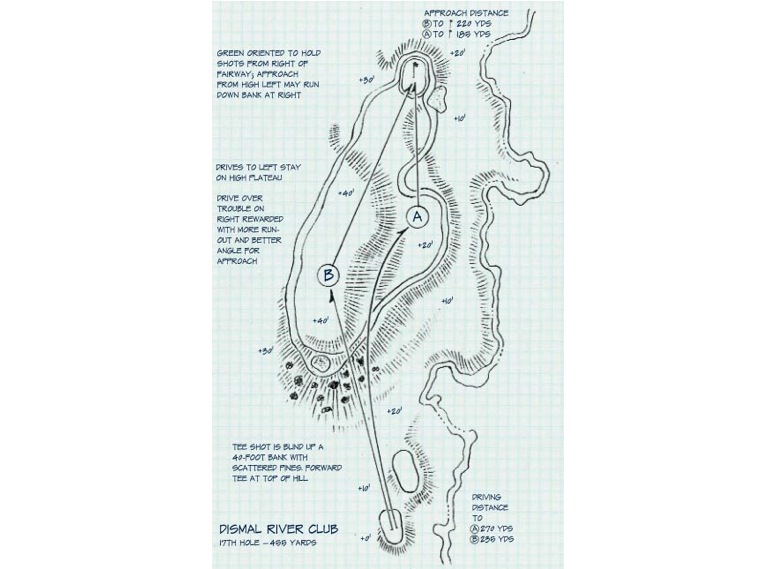

Dismal River Club – Red Course, 2013, Tom Doak – Par 4, 17th (Courtesy Renaissance Course Design) River Club – Red Course, 2013, Tom Doak – Par 4, 17th (Courtesy Renaissance Course Design).

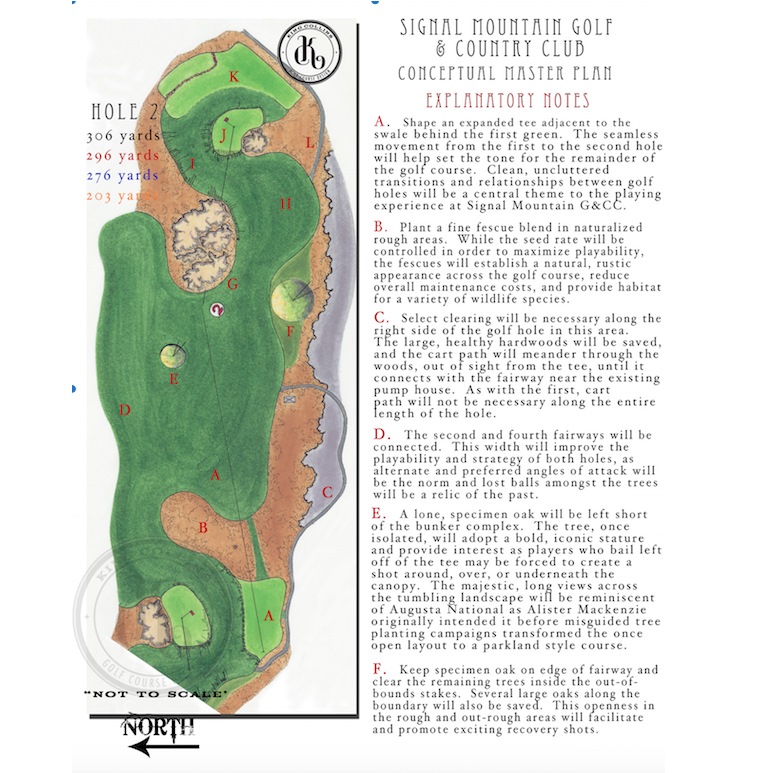

Signal Mountain Golf and Country Club, 2014, Master Plan – Par 4, 2nd hole. This unique double-fairway will move the current fairway width of forty yards to nearly two-hundred yards. (Courtesy King-Collins Golf Course Design).

“If you don’t have width, you don’t have options. Without options, there is no strategy. Without strategy, you have what amounts to a very one-dimensional game that is boring to the scratch player and not very fun for the bogey golfer.” – Rob Collins, King-Collins Design.

What exactly then is considered wide(r)? Pre-1950 in America, it was not uncommon to see 45-55 yard landing areas, regardless of the hole length on par 4’s and 5’s. After this period, single row irrigation exploded across America and courses became tighter, seemingly overnight. The ‘new’ wide became the edge of the sprinkler’s throw, shrinking fairways by some 20-40 yards on average.

The second death blow of width came after World War II with the rise of ‘penal architecture’, which is characterized by narrow fairways, bunkers often on both sides of landing areas, trees hanging over fairway entrances which serves to block otherwise ‘proper’ angles, water features which were pushed to the edge of greens, and the lack of bailout options especially around shorter holes. Penal golf demands the player hit to a specific target, with a specific shot shape, and often eliminates the option to play run up shots, a positive many golden age architects embraced.

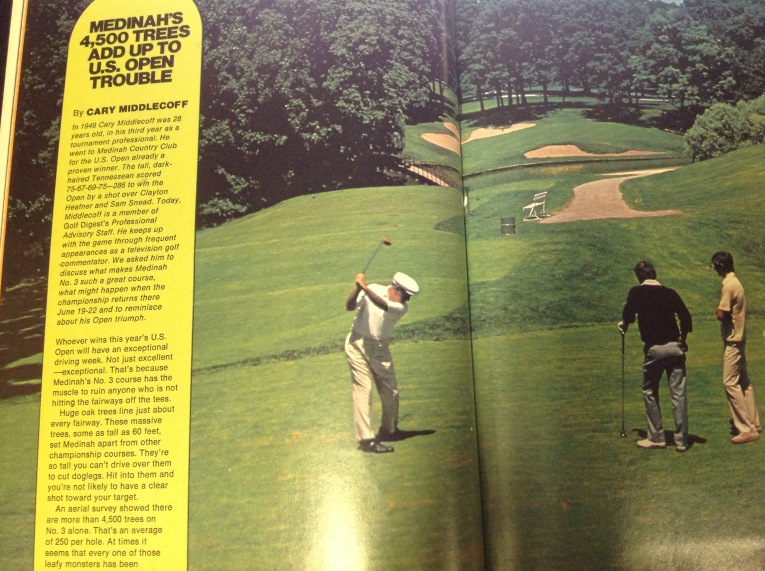

Lastly, the 1960’s and early 70’s became notorious for ‘re-designs’ by renegade Green Chairmen and Green Superintendents, mostly due to their desire for ‘leaving their mark’ and the rush to emulate the USGA Championship course selections of the era: Oakmont, Oak Hill, Baltustrol, Hazeltine, and Medinah. Since few wanted to be branded anti-environment, mowing patterns and tightening of holes via trees was widely embraced.

Medinah Country Club made the cover of Golf Digest – June, 1975. The article speaks of the over 4,500 trees or 250 trees per hole (average).

Many experts consider 1950-1985 to be the ‘dark ages’ of golf architecture, since few courses designed during this period occupy the top 100 lists.

All of this changed in the mid to late 90’s as many clubs began converting their archives to digital files. To their astonishment, many discovered the course they were currently playing looked nothing like their original architect intended. The first step in many cases was to uncover lost width, a hallmark of most of all of the golden age architects like Donald Ross, A.W. Tillinghast, C.B. Macdonald, Alister MacKenzie, Seth Raynor, and Perry Maxwell embraced.

Industry experts point to Oakmont Country Club as the poster child for reclaiming choked playing areas. Soon large to medium clubs of similar pedigree, like Merion, Winged Foot, Olympic Club, National Golf Links of America, Oak Hill, Garden City CC, Baltustrol, Old Town Golf Club, Carolina Golf Club, Pinehurst, Yeamans Hall, Aronimink, Medinah, Riviera, Inverness, and the Philadelphia Cricket Club began following suit to the point that width and multiple playing lines was and today still is the preference of Golfweek, Golf Magazine, Links Magazine, and Golf Digest raters.

A careful study of the top 100 courses in America further supports this design philosophy, as does the new course openings over the last twenty years from modern-day revivalists such as Tom Doak, Gil Hanse, Mike Strantz, Bill Coore and Ben Crenshaw.

It appears the USGA has finally gotten the memo as well with the recent U.S. Open selections of Pinehurst #2 (2014) and Chambers Bay (2015).

So why do some clubs resist width and instead demand that par must be defended by narrow, tree-lined fairways?

Part of the problem is ignorance – they simply don’t know any better. Another issue is the misplaced fear of some mythical, young iron Byron carding 59’s or 60’s every other week and ‘destroying the golf course’. The third issue? Vanity. No one wants to be a member of an ‘easy’ course. And the fourth issue is, most people don’t travel, and therefore don’t see what a fun, yet challenging course with width and properly designed greens can actually look like. Width in their minds usually equates to flat, lifeless fairways with matching pancake shaped greens.

Great example of fairway angles and width at two Tom Doak gems below:

“WIDTH IS KEY! When you start reducing width (and I mean air space as well as fairway width) you begin to reduce the number of options for players of various skill levels, thereby reducing the total number of players who can successfully navigate their way around the course. I guess that’s fine if we only want scratch to 10 handicaps playing golf.

The comment about wide fairways presenting no challenge to the good player is pretty weak, at least on our courses. Go check out any of our fairways and it becomes apparent that you must be in certain spots to gain an advantage on the next shot or approach to the green”. – Mike Strantz

Golf is supposed to be a game (meaning fun), not drudgery. Terms like “resistance to scoring” (a course rating creation), “a difficult par”, and “a stern test” are commonly heard on television and in the 19th hole…and frankly, they’re nauseating. Who really cares if a mini-tour player or college kid can shoot a 66 on occasion? Or that less than 1% of a club’s membership can play to scratch or better?

“…but we have to protect the course”.

From whom and to what end? Trying to prevent a zero handicap from shooting a 68 instead of a 70 (statistically, he can’t do it often any way) at the expense of 99% of the membership by shrinking fairways and in many cases adding trees in every imaginable space is a misguided position. Does anyone ever consider that they pay so little of the freight? So why is all of the attention focused on their games?

Golf is the ultimate mirror. Post a high score at a tough course, fine. But repeated high scores at what is considered an easy course? Not so fine. This is why even high handicaps (especially on Green Committees) will bemoan anything that might make their round more fun (or quicker).

Difficult courses obscure poor play.

My friend, Jason Thurman exposes the entire farce succinctly, “In a sense, the average player has been sold a bill of goods over the last 60 years starting with Robert Trent Jones’ rise as he’s been repeatedly told that a good course is synonymous with a ‘strong test’. In the process, he’s been taught to ignore his own enjoyment of the game and believe instead that good golf courses inflict punishment as opposed to rewarding good play. He’s also been taught that the best holes are ‘laid out in front of him’ as opposed to holding secrets that are unlocked through multiple plays and that reward the player with the cunning eye. There’s something empowering in the idea of Golden Age architecture and the way it believed as much in accommodating the handicap player as it did in challenging the strong player. Once the focus became more one-sided, the game became a little bit less interesting for everyone”.

Bogey golfers make up the bulk of the golf population. This doesn’t mean they need a dumbed-down version of the game but on any given weekend, we’ve all witnessed cold tops, high slices, and low, line drive-irons mixed with a few great and memorable shots. Does it really detract from the game if a guy shoots 96 instead of 100?

Narrow fairways usually indicate poor green complexes and in general, a weak overall design, otherwise why have them?

There are no decisions when the playing corridors are narrowed. No real daring play. It becomes a game of shortened swings, aiming, and defensiveness. Preferred lines? Angles? It is hard to make a case for being on the right or left side of a twenty-eight yard fairway. Narrow equals slow play and a day of frustration especially when the player has to continually reach into his bag for a new ball every few holes.

Width for widths sake isn’t the answer either though. Green complexes with creative slopes and angles ties the entire precept together. In other words, if the green dictates no advantage from either the left or the right of the fairway, then the point of width is mute, strategically speaking.

Look again at Dismal River’s drawing of the 17th above. Clearly there is a choice that has to be made from the tee box. How boring would the hole be if the entire right side were high grass and only the best player could reasonably make par? This is the essence of why width matters to both the bogey and the scratch golfer. Choice and strategy for the scratch, a little forgiveness for the bogey player.

Great green complexes, like below, complete the puzzle:

Massive width, along with an equally impressive and beguiling green complex at Cabot Links, 4th hole (Rod Whitman, 2012).

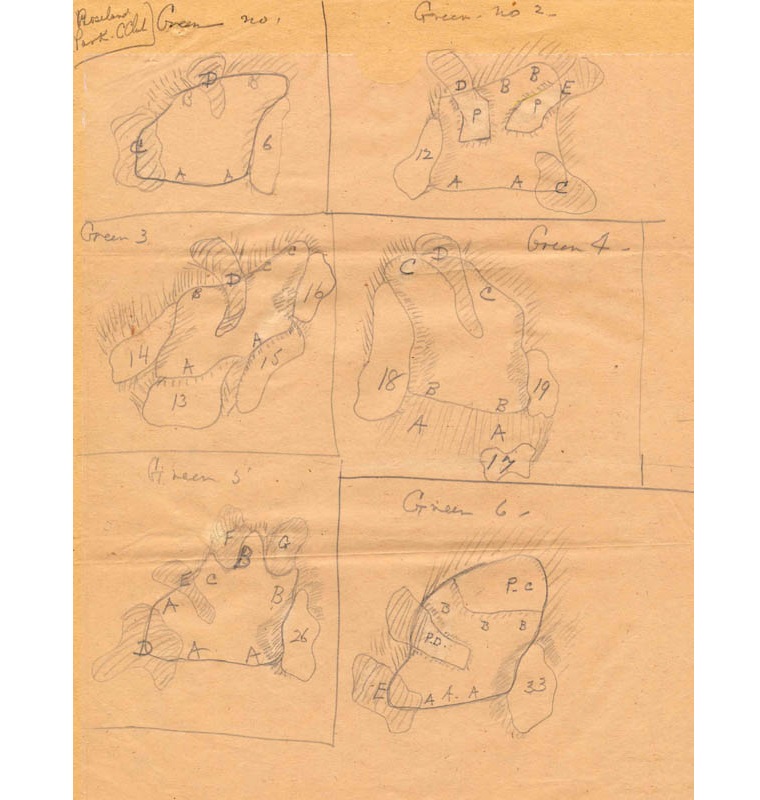

Roseland Golf and Country Club – Green drawings, Donald Ross, 1921 (courtesy Tufts Archives, Pinehurst, NC).

“I love fairway width, and the angles that can be employed by using it strategically. The architect can build slope into the fairway, put in turbo boosters on one side and not the other, and have some real fun. It was one of the things that first struck me about Pine Valley other than the greens. You have great room to hit it, but choices of angle are fraught with their own challenges. The par four thirteenth is a perfect example of this as it looks like your tee shot should be down the left side, cutting the distance for your second shot . This is problematical, however. If you don’t hit it far enough it rolls back into Holman’s Hollow. If you hit it big but overcook it it can kick left into a nasty waste bunker, which is really bad . The correct play is to hit a draw down the right center, even if it leaves you a longer shot in to the green . It’s real wide but the perfect slot is quite hard to find”. – Archie Struthers

Isn’t this the essence of the most interesting, memorable, and fun holes? Decision-making. Taking chances at different times during a round. Playing alternate lines with different clubs.

The truth is, we all want to be able to control the golf ball and maneuver it in a way that was equal to or better than our last round, but the game is quite hard for many. Hard in the fact that par for the great majority of players is only met a few times per round. In its simplest form, golf is recreation. I’ve never met a golfer who had a bad time hitting fairways and was either on or around the greens on a given day, but have met quite a few who have walked off the last green frustrated because the course demoralized him.

“But it is the green end where the golf course should present the most scoring difficulty. This just requires that the green have enough tilt and be fast enough that anyone is in trouble if they’re above the hole … which prevents even the pros from taking dead aim at the hole.

The advantage of defending the course at the green end is that you can ADJUST the difficulty by tuning the speed of the greens up a notch for an event and down a notch immediately afterward. This is a lot more practical approach than narrowing the fairways and fertilizing the roughs, which takes months to prepare and weeks to un-do”. – Tom Doak

The game can be challenging and fair for both the highly skilled and highly enthused. It makes little sense to try and punish the best players at the expense of the rest when both can be satisfied. Width is often the deciding factor.

The End

___________________________________________________________

Special thanks to Benjamin Litman (Barnbougle Dunes), Mark Saltzman (National Golf Links and Prairie Dunes), and David Moriarty (Rock Creek) for their photo contributions.