Flossmoor Country Club

by Greg M. Ohlendorf

Introduction

A portion of the material that follows was first printed in the Flossmoor Country Club media guide, which was published to introduce the renovated course to the national and local media. A number of people have contributed to this effort including the family of Herbert J. Tweedie, the direct lineal descendants of the club’s original architect who provided significant information for the story of their great-grandfather.

Also, special thanks goes to fellow GCA member Dan Moore who is working on a book that will chronicle the courses from the beginning of golf in America up until the Golden Age. Flossmoor is one of those courses that Dan has studied, and he has graciously allowed me to include his story on the architectural history of the club that he has discovered during his research. So we will begin with his material, and I will pick up with the remainder of the Flossmoor story after that.

Architectural Evolution of Flossmoor Country Club

by Dan Moore

Founded in 1899, Flossmoor Country Club (originally Homewood Country Club) has a long and intriguing architectural history. According to the 1901 Chicago Green Book, the original course was laid out by Chicago golf pioneer H. J. Tweedie, member Dr. H. W. Gentles, and club professional Jack Pearson. The course has evolved over time, with many notable changes made by Flossmoor professional and greenkeeper Harry Collis, who reconfigured the course in 1915 to accommodate a new clubhouse location following the Club’s second devastating clubhouse fire. Under Collis, Flossmoor reached its architectural and pinnacle in the Roaring Twenties when it hosted the 1920 PGA and 1923 U.S. Amateur. A recent update by Ray Hearn has restored Flossmoor’s position as one of the elite courses in the Chicago area.

The Curious Case of Herbert J. Tweedie, Dr. H. W. Gentles, and Jack Pearson

Herbert “Pops†Tweedie (1864-1906) was born in Bombay, India, to Scottish parents in 1866. Tweedie spent his formative years in Hoylake, England, where his father was a founding member of the Royal Liverpool Golf Club in 1869. Growing up next to the links, Tweedie learned the game alongside the great English amateurs John Ball and Harold Hilton and twice defeated Ball to win Hoylake’s Junior Championship in the 1870s. The Tweedie family relocated to Chicago in the 1880s. Tweedie was instrumental in working with Charles Blair Macdonald to establish golf in the Chicago area.

When he died at age 41 in 1906, Tweedie was the leading golf expert and architect in the Chicago area who was responsible for laying out over 30 courses, including such noted early courses as the Glen View Club (1902 U.S. Amateur and 1904 U.S. Open ) and Midlothian Country Club (1914 U.S. Open).

Much less is known about Flossmoor’s first professional Jack Pearson. What is known is that he was a long hitter who hailed from Fife. When contacted by Dr. Gentles to come to Flossmoor, Pearson was working at East Middlesex Club outside London. He was a frequent playing partner of the great James Braid, who, in addition to his résumé as a champion golfer, was also a fine architect. It appears that Pearson spent two years at Flossmoor, 1900-1901, and spent the winters working as a golf professional in Ocala, Florida. Despite its unfinished state, the 18-hole course was inaugurated on a September 8, 1900, with a match between Pearson and Alex Smith, who was the professional at Washington Park. Smith defeated Pearson 5 and 4. He would later win the U.S. Open in 1906 at Onwentsia and again in 1910 at the Philadelphia Cricket Club, and would win his second Western Open title at Flossmoor in 1906.

There is some discord in the record regarding who designed Flossmoor’s original course. A number of sources indicate that Tweedie laid out the course with the Chicago Daily Tribune reporting Tweedie was on site working to lay-out the course in April 1900. However, The Tradition Endures, Flossmoor’s centennial book from 1999, contains a 1948 letter from original member Dr. H. W. Gentles that muddies the picture by claiming he and Jack Pearson were responsible for the original course. Gentles contends that Tweedie completed an initial routing which was less than satisfactory. According to the letter, he convinced the club to let him hire Pearson, and he and Pearson made changes to the course to eliminate a poor start and to take better advantage of the potential in the south end of the course, where the back nine is located today. Among Gentles’ complaints was that all three nines of the 27-hole course could not finish at the house, a problem that was not remedied until 1915. The 1901 Green Book, which given the nature of the information listed must have relied on information supplied by the Club, credits the layout of the course to Tweedie, Gentles, and Pearson. This authoritative source establishes some degree of involvement by Gentles and Pearson while not discounting the role of Tweedie.

In that era, as now, it was customary for club officials and professional staff to assist an experienced architect. For example, the Green Book gives credit to Tweedie and two club officers at Midlothian as well. There is no evidence that Gentles and Pearson were involved in the design of any other course before or after Homewood, whereas Tweedie was a well-known and accomplished architect. Perhaps 50 years later Dr. Gentles confused the process of constructing the course and making early improvements with the initial layout of the course. In any event, absent compelling evidence to the contrary, it is far more likely that Gentles and Pearson assisted Tweedie, or made some later modifications to his layout, rather than rejected his work entirely. Until it can be conclusively proven otherwise, the Flossmoor’s view that Tweedie should be credited as the primary original architect of the original Homewood CC course is upheld.

The Original Course

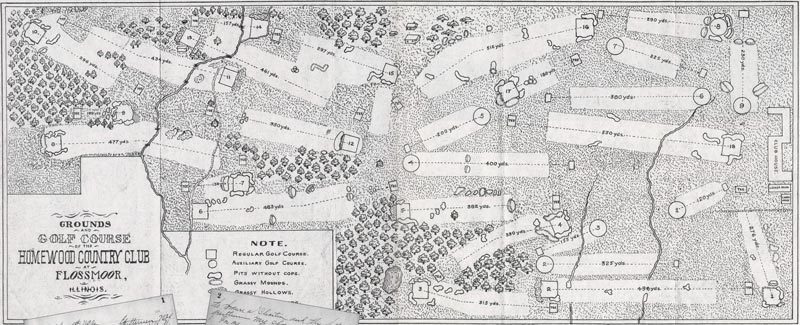

The earliest routing plan available, shown here, dates to the Chicago Inter Ocean’s 1901 Green Book. The original routing started at the clubhouse, which was located on the north end (the left side of the map) of the property. Like the links courses in England and Scotland, the course ran out to the south end of the property before turning back and returning to the clubhouse. An auxiliary nine-hole course, which no longer exists, was built in the middle of the north end of the property. Similar to other Tweedie layouts from the gutty era, when drives of the best players traveled just 180 to 200 yards, Flossmoor when it opened was a very long course, coming in at 6,100 yards.

Like most courses from the early years, the course was slow to round into form and took time to reach its full potential. By the September 1900 opening, the greens were reported to be in very rough condition, and in early 1901 Pearson was still completing work on the greens. Other reports indicate that bunkers were added in 1902 and that bunkers “along the most current scientific lines†were added in 1904 to combat the new rubber core ball. A significant change to the course was made in 1903, when the greens on the 16th and 17th holes were both moved to their present locations on top of the ridges formed by the old banks of Butterfield Creek. Perhaps these were the changes Dr. Gentles felt were needed to improve the south end of the course. Ever since the green was moved up on the ridge next to the old farm cottage, the long 17th has been considered one of the best holes in the Chicago District. It was included in a 1917 Chicago Daily Tribune survey of the best 18 holes in the country conducted by Beverly CC professional George O’Neil.

When assessing an architect of Tweedie’s era, it is important to understand the limitations of that period. Architecture at the turn of the century consisted primarily of laying out the routing of the course. Construction techniques and budgets were minimal and greenskeeping techniques and staffs were rudimentary. The emphasis among the best architects was on the routing where they worked to fully utilize the natural features of the course and locate tees, hole corridors and green sites accordingly. That Flossmoor was laid out with uncommon architectural skill for the era can be seen in the magnificent use of Flossmoor’s natural landforms on such Tweedie originals as 11, 12, and 15.

The 11th, Spion Kop, is only a little longer today than when Tweedie laid it out as a 130-yard par 3 in 1900. It features a terrific uphill approach to a well-bunkered green set on a plateau. The green, one of the best on the course, flows with the natural slope of the land from front left to rear right. The hole was named after a hilltop fortress that was pockmarked by artillery shells in the Battle of Spion Kop on January 24, 1900, a turning point in the Second Boer War.

The 12th was originally a 450-yard par 5 with the tee adjacent to the 11th green. The drive from the hilltop needed to be placed in the valley as close to the creek as one dared. The second was blind, up and over the crest of the hill, then downhill the last 100 yards to another fantastic bunkerless green running away from the player with the natural slope of the hill. Still a wonderful hole today, one can only imagine how good this hole was in 1900.

The 15th, another of Flossmoor’s many distinctive par 4’s, is described by the Club as one of the best driving holes anywhere. A large oak guards the left side of the gentle dogleg left and the fairway drops into the valley formed by the old creek 190 yards from the hole. The creek must be traversed on the way to the green. A green expansion by Hearn has added several new hole locations.

Despite dramatic changes in the game and a relocated clubhouse, it is quite remarkable that today’s course retains much of Tweedie’s initial routing and many of the best holes follow the imprint of the Tweedie originals.

Flossmoor Evolves

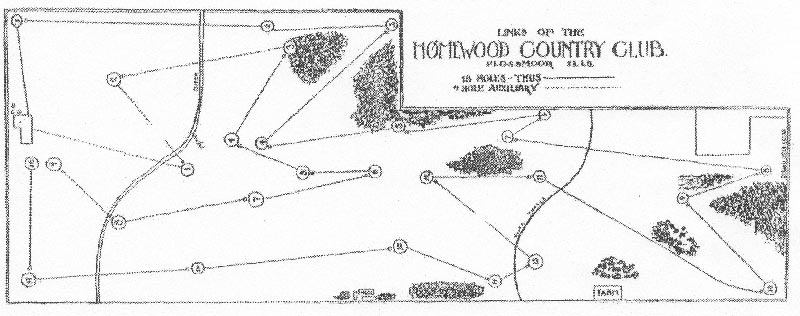

Like many courses built during the era of the gutty, Flossmoor had to adapt to changes in the game and has evolved over time. Marked by the opening of Charles Blair Macdonald’s National Golf Links of America, golf course architecture was rapidly evolving by 1910. New construction techniques, advances in agronomy, and an emphasis on strategic design were taking hold. It was around this time that unconfirmed reports indicate Scottish architect Willie Watson may have added two new holes in 1910 while he was engaged to expand the nearby Ravisloe Club to 18 holes. While documentation of Watson’s involvement may be sketchy, it is clear that what are now the 2nd and 3rd holes were modified between the Western Opens of 1909 and 1913. The new holes (17 and 18 as shown on the 1911 map) were a well-bunkered 180-yard par 3 and a 550-yard par 5, which encountered a small creek on the way to what was then the home green, located directly in front of the clubhouse porch. They replaced a pair of short par 4’s including the 280-yard 18th, which approached the west side of the clubhouse in what must have been viewed as a weak finish.

The Collis Era

While Flossmoor’s routing still follows much of Tweedie’s original layout, several holes and the green complexes of the course can be attributed to an English import from Blackheath, Harry Collis, who worked at the club from 1905 until 1929. A fine player, Collis was originally hired as the Club’s professional in 1905. At the urging of the Club’s president, Collis took over full-time greenskeeping duties in 1911 with the responsibility of bringing out the full potential of the golf course. Collis immediately began upgrading the course and eventually became known as an accomplished agronomist who created a popular grass mixture for putting greens called Flossmoor Bent.

Collis’ most far-ranging improvements followed the devastating 1914 clubhouse fire and the decision to relocate the clubhouse to the middle of the property on the west side of the grounds. The clubhouse move eliminated the original out and back links style routing to enable both nines to start and finish at the new clubhouse. Collis went to work on the course and in 1915 he debuted two holes: a short par 3 7th hole, which called for a mashie shot over a pond, and a new finishing hole that combined the old par 3 14th and par 4 15th holes into what is now the uphill par 5 18th hole with its green located in front of the clubhouse (as it was on the old 18th). Reports from 1915 also indicate that Collis reconfigured the 14th into a tricky 296-yard par 4 that rewarded placement over length to create a hole that adds great character to the course. At some point, Collis added the signature Flossmoor bunker to the 16th hole, which was previously unprotected in the front (the grass fangs are not visible on the 1939 aerial and probably were a later addition). To accommodate the new clubhouse, the first tee was pushed east, creating a gentle dogleg to the right.

Another important Collis addition to the course came when he shortened the 5th hole from a par 5 to a 447-yard par 4 and moved the tee on the 6th hole back by 100 yards, creating a slight dogleg right. Originally just 315 yards, the 6th was extended to 417 yards. Homewood’s homegrown champion golfer Warren K. Wood considered the new 6th the best hole on the course in the 1920’s. Bobby Jones labeled it “The Difficult Sixth†after Max Marston made the first of three consecutive birdies in the afternoon round of their match to start a stirring comeback that paved the way to Marston’s victory in the 1923 U.S. Amateur.

The hand of Collis is most clearly evident in Flossmoor’s remarkable green complexes. Collis’ Flossmoor Bent can still be seen in the pleasing variety of green, yellow, red, and brown hues, which lend a mottled, old school look to the green surfaces. The smooth, quick greens are quite varied with some on the smaller side and others quite large. Many, like the 11th and 12th, take full advantage of natural slopes, and others like the 4th, 6th, and the treacherous 14th have slopes which flow off mounding built into their green pads. Green side mounds built by Collis are a unique characteristic of Flossmoor. A particularly noteworthy example is the use of small mounds surrounding the bunkerless 12th green, which creates a punchbowl effect.

Collis was also known for rugged, deep, oval greenside bunkering, which can be seen above in the 1923 photo of the sixth green.

In addition to his duties at Flossmoor Collis also worked on the side as an architect, often teaming with Olympia Fields professional Jack Daray. A nearby public example of their work can be found at Glenwoodie Golf Course, which features excellent greens and a back nine with a remarkable similarity to Flossmoor’s. Most would agree that Collis’ best work can be seen on the ground in Flossmoor.

Flossmoor Today

Like many courses today, tree encroachment, green shrinkage and erosion of bunkers had taken its toll on Flossmoor by the time of its centennial celebration in 1999. Recognizing the need to recapture its former glory, the Club engaged Ray Hearn in 2006 to develop a long-term master plan. The work completed in 2008 includes a brand new par 3 13th (replacing a hole many have cited as a weak link of the course) and a newly located green perched perilously close to a pond on the long par 4 8th. Both greens are surrounded by closely mown chipping areas, which add to the options around the greens. This feature has been combined with a program of green expansion on several other holes, including the 7th. An intriguing example of green expansion took place on the 12th, where the green was extended out to the mounds surrounding the green.

Another notable change by Hearn was made to the 319-yard 4th hole. Previously featuring a lackluster blind drive yet possessing a green of very high merit, the 4th didn’t live up to its potential. Hearn eliminated the blind drive by bulldozing the hill and opening up a sweeping view of the fairway. Removal of some withered old trees and a significantly widened fairway on the right, combined with carefully placed fairway bunkers, have created a variety of options, all now fully visible from the tee. The result is a very fine short par 4 hole possessing genuine strategic merit.

Throughout the course, worn-out ovals have been replaced by elegantly understated bunkers built in the 1920’s style of George Thomas; some are new to address changes in the game and some are restorations of historic bunkers. A remarkable job has been done with tree removal, particularly on the back nine, opening up vistas previously enshrouded in overgrown willow trees that choked the finishing holes. With the addition of Ray Hearn’s new par 3 13th hole, the back nine is as good as any in the Chicago area.

Flossmoor provides a genuine, broad-shouldered style of golf demanding long and accurate play and a deft touch around the greens. One might quibble that the early holes are built on less than inspiring land and that too much of the course runs north and south so that there is some monotony with how to combat the wind. However, the combined contributions of Tweedie, Watson, Collis and Hearn have created a course with a character and personality all its own. This is due to the foundation laid by Tweedie’s long and bold original layout that has stood the test of time, the nature of the terrain which was superbly utilized on the back nine, and a superb set of Harry Collis greens which are unique to Flossmoor.

In 1913 when the great English Golf writer Bernard Darwin visited, he concluded the strength of the course was found in its long par 4’s, which are now complemented by Harry Collis’ greens, interesting short par 4’s, and picturesque par 3’s. With the completion of the renovation, Flossmoor has rightly reclaimed its place among Chicago’s elite courses and remains today, as Darwin concluded in 1913, “a good, honest searching test of golf.”

Architectural Evolution of the Course

Course opened for play in 1900

Holes 1- Tweedie original. Tee on first hole moved 50 yards east in 1915.

Holes 2-3: New holes by Willie Watson built in 1910. The 3rd hole changed to a par 4 in 1990.

Holes 4-6: Tweedie originals as modified over time by Collis. The 4th tee and green were moved back from original positions by Collis. Hearn modified the 4th in 2008 to remove the blind drive and widen the fairway to create more options. Collis converted the 5th to a par 4, which allowed the 6th to be lengthened by 100 yards and bent into a dogleg around the trees.

Hole 7: Collis original 1915. New Gilley tee added about 1990.

Hole 8: Tweedie original tee location and hole corridor. New green in 1990. New Hearn green in 2008.

Hole 9: Tweedie original hole corridor. Expanded to par 5 in 1990

Holes 10-12: Tweedie originals. The 10th green was relocated closer to the creek. The 12th has been shortened and converted to a par 4.

Hole 13: Hearn original 2007.

Holes 14-17: Tweedie original hole corridors. Collis updated the 14th hole in 1915. Green on the 16th and tee and green on the 17th moved up the hill to present locations in 1903. The signature fanged Flossmoor bunker on the 16th was added by Collis.

Hole 18: Collis original 1915. Combined a par 3 and 4 into the present par 5. New green by Dave Esler in 2000’s.

© Daniel Moore

Club Background

One hundred and ten years is a long time and, in America, it’s a very long time in the country club business. There are courses in the country that are a bit older than Flossmoor Country Club, but quite a few of them have been significantly remodeled or in some cases actually moved from their original locations. Flossmoor sits on the same piece of ground that it was built on, and 13 of the holes remain in the same basic corridors from the beginning. Three additional holes were modified during the first 10-15 years of the club’s existence (and remain there today) and only two holes were entirely rebuilt during the club’s recent renovation program.

But as time passes, most clubs reach a point where decisions about the future need to be addressed. Three and one-half years ago, Flossmoor found itself at one of those points. Over the previous decades, a number of well-intentioned tree planting programs had changed the look and feel of Flossmoor, and unfortunately, not in a positive way. The course had become very linear, with the only viable option of play on many of the holes was hit it as far down the centerline as one could. Players who hit their ball a bit right or left would likely find themselves stymied behind trees that would make advancing their next shot toward the green very difficult. Those same trees were having a negative impact on the agronomy of the tees and greens as the required amount of sunshine bent grass needs in the Midwest was not getting to those surfaces. The course’s superintendent, Bob Lively, was being asked to perform miracles to keep the turf in top condition (and Bob was doing an amazing job in this area despite the challenges).

Behind a committed board of directors, the club hired Raymond Hearn to consider what to do with one specific hole, the 18th that had over 20 willow trees “gracing†the right side of its fairway. The club wanted to know what the options were for the hole if these trees were removed. Hearn provided a one-hole “master plan†which was ultimately approved by the board, and that plan propelled the complete renovation project forward. More on that later, but for know, let me take some time to make the GCA group more familiar with Flossmoor Country Club.

It All Began in 1899

As is the case with most of the country club’s located south of Chicago, Flossmoor came about due to its proximity to the train line coming out of the big city. The founders had begun planning for the course and recruiting members in 1899. The course was originally named Homewood Country Club, and back on January 21, 1900, the article below appeared in the Chicago Times-Herald.

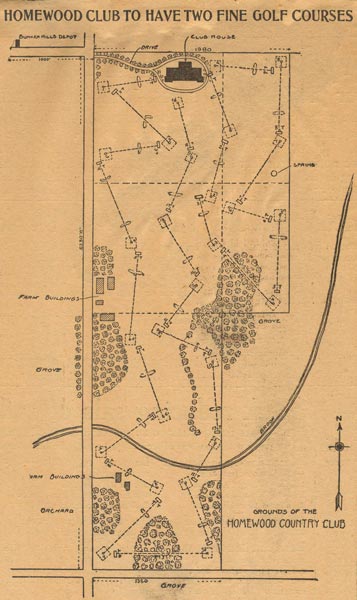

Homewood Club to Have Two Fine Courses

Forty more acres have been leased by the officers of the Homewood Country Club, and the total tract of land purchased and leased now comprises 240 acres. The two golf courses have been tentatively laid out, one of eighteen and the other of nine holes. The regular course is to be so arranged that the ninth hole will be located farthest from the clubhouse, so that players will have to make an eighteen-hole circuit before getting back to the starting point. It will be 5,800 to 6,000 yards in length, each nine being practically the same length. The nine-hole course is to be kept on par with the longer course, and will be better than most so-called practice courses. On it members can play when they do not wish to make the longer circuit, or on days when club matches are being played on the long course. Work upon the clubhouse will begin early in the spring. The structure is to coast from $16,000 to $20,000, and will be strictly up to date in all respects. The stock company formed for the purchase of the land is capitalized at $28,000, eighty members holding two shares of stock at $100 each, and six life members each holding twenty shares. Fifty other members besides the stock members will also be taken in. Special arrangements with the Illinois Central Railroad are under way, including the construction of a station about a mile south of the present Homewood station and special dining car service. It is proposed to call the station Bunker Hills, and it will be just twenty-four miles from Randolph Street. An effort will be made to have a dining car run from Randolph Street every Saturday noon, and possibly daily during most of the summer. Sixteen trains a day will run each way from the new station, express trains running in thirty-five and regular trains in fifty minutes.

This photo as part of the membership recruitment effort for Homewood CC in 1899-1900. It shows a proposed layout for the course and an auxiliary course. The routing shown above was never built as the original first hole ran due east rather than due west!

History of the Course and the Players Who Played There

There have been many significant events held at Flossmoor Country Club that have included many of the game’s greats. Flossmoor was a challenging tournament course as the following excerpts from some of the major publications from the time illustrate.

It all began on the first day, September 10, 1900. The New York Times reported that a new 6,100 yard golf course named Homewood Country Club had just opened. Alexander Smith, brother of 1899 U.S. Open champion Willie Smith, and J.S. Pearson, a new Scottish professional, played the first game over the links, Smith winning by 5 up with 4 to play.

One of the first major events fielded at FCC was the 1906 Western Open. A great rivalry at the tournament was waged between Alexander Smith and Willie Anderson. Both had come to the States to teach Americans how to play the difficult game of golf. Flossmoor then played at 6,141 yards with a bogey of 82 (this was considered the “par†score in the day). Smith would go on to win two U.S. Opens and two Western Opens, while Anderson would claim four of each. The Western Open was considered almost the equal of the U.S. Open during those days. Smith proved the better that year and took home the $150 first place prize check. He won the U.S. Open at Onwentsia CC the following week.

In 1909, the Western Amateur came to Homewood. The young 19 year old Chick Evans, who played out of Edgewater Golf Club, found himself in the finals against Albert Seckel of Riverside Golf Club. The two had met on many previous occasions in other junior and intercollegiate tournaments. Flossmoor’s own member, Warren Wood, had taken the medalist honors of the stroke play part of the tournament. Evans got off to a great start in the 36 hole championship match going up six after only eight holes. Through twelve, Evans stood seven up after hitting a 140 yard mid iron to 10 feet, which he converted for birdie. Seckel fought back, though, and won 15 ~ 17, sending the match to lunch with Evans four up, where he stood on the 11th tee (the 15th today) of the second round.

Evans then lost the 11th after knocking Seckel’s ball back to him, seemingly having the hole. Unfortunately, Evans was told by the official Tom Bendelow that such a move was against WGA rules, and the hole was awarded to Seckel. His lead was further cut to two when Seckel made a 20-footer for birdie on 15. And after making bogey on 16, Evans lead was down to one. The players halved 17 with threes to make the match dormie. After both players made five on 18, Evans had secured his first national title. He would go on to win eight Western Amateurs, a U.S. Open, two U.S. Amateurs, and many other tournaments over his illustrious career.

In 1913, the Western Amateur returned to Homewood (which would change its name officially to Flossmoor the next year). Homewood’s own, Warren Wood, would become the winner, defeating Ned Allis of Milwaukee 4 and 3. Allis had opened his second qualifying round with an ace on the 306 yard first hole (the 4th today). Chick Evans was medalist by a stroke over Wood with a 151.

In 1914 after a second devastating fire, the clubhouse was moved to its current location and the holes were renumbered accordingly.

During the Great War in 1917, Flossmoor hosted one of the Red Cross Matches, which were being held around the country in an effort to raise money for the Red Cross. Bobby Jones, Perry Adair, one of Bobby’s childhood friends, and two young ladies, played in many matches throughout the summer. Perry and Bobby had earned quite a reputation as outstanding young golfers, and they were dubbed the Dixie Kids. They were ultimately paired in a match at Flossmoor against Chick Evans, the reigning national amateur and U.S. Open champion, and Robert Gardner, a former amateur champion. The youngsters got handed a firm beating. Later that summer, however, Jones and Adair beat Evans and Warren Wood in a match in St. Louis.

During July, 1918, another Red Cross Match was played at Flossmoor, this one featuring Chick Evans and Warren Wood playing against Max Marston and the reigning Metropolitan amateur Champion, Oswald Kirby. Kirby was asked to name the best hole he had ever seen by Chicago Tribune columnist, George O’Neil. On the day of the match, Kirby selected his favorite as the 17th at Flossmoor. Later that afternoon, as fate would have it, Kirby and Marston closed out Evans and Wood with a four at number 17!

The third annual PGA Championship came to Flossmoor in 1920. The PGA was conducted as a match play tournament until 1959 and the pre-tournament favorite was the great Jim Barnes, who had won the first two PGA Championships. The ultimate winner of the event was Jock Hutchison who got into the field only after two other pros sent their regrets. He was the head professional at Glen View Club at the time. Jock had won the Western Open and finished tied for second at the U.S. Open, but had failed to qualify for the PGA. Jock won 1 up over J. Douglas Edgar of Atlanta, but not without a fight.

The August 28, 1920 edition of The American Golfer reported on what they called “one of the greatest single shots ever played in an American tournamentâ€. On the 34th hole, Jock was one up when his drive found itself tight against the forward side of a bunker 200 yards from the 16th green. The risk was that Jock’s club could easily hit the bunker prior to striking the ball. He was clearly in trouble. Jock first took his wooden spoon, then changed to a shorter mashie, and then went back to the spoon. It was estimated that he didn’t miss the bunker edge by 1/4â€, but missed it he did. His ball sailed toward the green and stayed on. After two putts, he had secured his four. Edgar, after seeing Jock’s miraculous shot, misplayed his second, barely hitting the green and proceeded to three putt to lose the hole. Even though Edgar won the 17th, the match ended on the 18th after both players made par. Hutchison won the Wanamaker Trophy and the $500 first place prize.

The next big event, the U.S. Amateur, was held in 1923. On September 14, 1923, the Chicago Daily Tribune wrote, “The arrangements at Flossmoor are the most complete ever made for an amateur tournament. There are Red Cross stations, a police station, hot dog, lemonade, soft drink, and sandwich tents, information desks, special telephone equipment, rest rooms, and a hospital, which may lead people to think that golf is a brutal game. There will be doctors and ambulances ready to rescue those who fall by the wayside trying to follow the golfers over miles of velvety turf. The big innovation at Flossmoor has been the erection of a grandstand overlooking the eighteenth green, where the crowd may park itself when weary of walking to watch the incoming aspirants for (Jess) Sweetser’s crown finish their rounds.â€

The event started off with tremendous intrigue. The medal round featured a showdown between Chick Evans and the great Bobby Jones, when both players went out and shot 1 over 149s. Unfortunately, both players were bounced from the match play portion of the tournament by the third round. Since they had both lost early, they decided to “play-off†their medal round tie the next day. Jones later wrote about that round in his book “Down the Fairway†by saying, “I carried a crumb of comfort from Flossmoor, and a valuable lesson in tournament golf. Chick Evans and I were tied at 149 for 36 holes of medal play – par at Flossmoor was 74 – and as both of us were erased early in the match play we got together to set the medal in a playoff the day after Marston had beaten me. I set a new medal course record with 72 and won the round, Chick having 76…Then I got to wondering why the devil I didn’t play that way in matches. And that was the lesson I learned. That was the answer for me. If I could only manage to shoot against Old Man Par in the matches, as I did in the medal play events, and (to be impolite) let my opponents go to the devil, why, maybe I wouldn’t run into so many hot rounds, or when I did run into them, I wouldn’t be so much affected. I decided to give it a try anyway…â€

Max Marston did win the Havemeyer Trophy that year by defeating both Bobby Jones, Francis Ouimet, and then Jess Sweetser in the finals. The match against Sweetser went to the 38th hole, which was the longest match in championship history at that time. By the time they had reached the second hole for the third time, a crowd of 4,000 had surrounded the green. Marston left his birdie putt short, but directly in Sweetser’s line, the third stymie Marston had laid against Sweetser in the last four holes. Due to the “don’t lift†rules of the day, Sweetser missed and Marston won the Amateur.

Flossmoor had earned itself quite a reputation by the early 1920s. In 1927, Bobby Jones won the British Open shooting a spectacular 285. Some felt that the modern ball had “softened up†St. Andrews. A newspaper correspondent at the tournament, though, called St. Andrews “the hardest course in the worldâ€, in an attempt to make Jones’ accomplishment seem more amazing. Golf Illustrated, stated that “the ‘auld gray links’ is less of a severe test of golf than Oakmont, Flossmoor, Lido, Pine Valley, The National, Inwood, and many other American linksâ€.

A couple of years later, in 1928, Bobby Jones returned to Chicago as captain of the Walker Cup team. He played ten practice rounds in the area leading up to the event. Eight of the ten rounds were under 70, he averaged 68.5, and set three course records in a span of four days (the first two at Old Elm and Chicago Golf Club) during this run. The last of these ten rounds was at Flossmoor, where Jones shot a course record 67 with seven straight threes beginning on the 8th hole! With the 32 he had made on the second nine at Chicago the day before, coupled with his 67 at Flossmoor, Jones had shot 99 for 27 consecutive holes, according to the October, 1928 edition of The American Golfer. The U.S. went on to win that Walker Cup 11-1, the most lopsided of the first five of these matches. Jones’ course record at Flossmoor was held until 1984 when Nick Zambole shot 66 in the first round of the Illinois Open. Twelve years later Mark Egge broke that record with a 65, which still stands today.

Data for this article was complied from stories in The New York Times, Chicago Daily Tribune, Golf Illustrated, The American Golfer, “The Tradition Endures†(the 100 year history of Flossmoor Country Club), and “Down the Fairway†by Robert T. Jones, Jr.

The Story of Hebert J. Tweedie

One part of the Flossmoor story many may not know much about revolves around the club’s original architect, Herbert James Tweedie. Tweedie was born in Bombay, India on July 26, 1864, just across the road from the famous writer, Rudyard Kipling. In 1867, he moved with his family to Liverpool, England, and then to nearby Hoylake. This is the home to the Royal Liverpool Golf Club where the 2006 British Open was staged.

Living so close to the famous links obviously had an influence on young Herbert. By the age of 11, Herbert had won the Boy’s Medal at the club two years in a row, which was quite an accomplishment as the event was open to boys up to the age of 15. He would win a number of other golf events in the area over the next several years.

He was married to Mary Armson on September 15, 1886. They honeymooned with Herbert’s entire family at Niagara Falls on their way to Neosho, MO, where Herbert was to assist in managing livestock. The venture failed though, so a new career in sporting goods and golf was soon launched in Chicago. Herbert became a golf representative with AG Spalding & Brother managing the Chicago store for the rest of his life. He was also the western golf manager for Crawford, McGregor & Canby Company of Dayton, OH, at the same time manufacturing golf clubs and designing golf courses.

In Cornish and Whitten’s “The Golf Courseâ€, Tweedie was credited with laying out the following courses: Belmont, Bryn Mawr, Exmoor, Homewood (now Flossmoor), Glen View, LaGrange, Midlothian, Park Ridge, Hinsdale, Rockford, Washington Park, Westward Ho, Maple Bluff, and a remodel with James and Robert Foulis at Onwentsia.

The work on the nine hole Belmont Course in 1892 became the original location of Chicago Golf Club, of which Herbert was a founding member. When the Chicago club moved to Wheaton in 1894, he built a new course at the Belmont links and became the club’s president for three years.

Herbert’s wife died in 1904 at the age of 39, and Herbert himself passed on July 11, 1906, two weeks short of his 41st birthday. A number of members of the Tweedie family still live in the Chicagoland area. Herbert’s grandson, Edwin, hired a genealogist in 1990 to compile the Tweedie Family History, where the majority of the information presented above was gathered.

Material for this article provided by Edwin Tweedie, grandson, Douglas Tweedie, great-grandson, and Ellen Wyckoff, great-granddaughter of Herbert J. Tweedie.

American Golfer – July, 1909 Story

In July 1909, The American Golfer magazine ran an article describing some of the holes on the course as the club prepared for the 1909 Western Amateur, which was won by Chick Evans. The author of the story, “Lochinvarâ€, noted that he wanted to “describe the holes which delight the heart of the true golfer, albeit that they may often prove the cause of unutterable anguish to him that lacketh the skill in the game.â€

“Lochincar†goes on to detail a number of his favorite holes. He begins as follows, “Take for example the seventh hole (today’s 11th); a short one, only 140 yards, but the green is on top of a low hill, at the foot of which yawns a real hazard, a goodly pit filled with sand, and at times profanity. Trouble awaits the timid player, who through fear of the pit, uses a too powerful club, and that he pulls or slices is justly punished. It is a fine hole.â€

“The eighth hole (460 yards) (the 12th today) is also worthy of mention, being well planned to reward good play. The green lies at the bottom of a hill, the summit of which is some 340 yards from the tee. Two fairly good strokes will give the player a clear view of the green and a short approach to the hole; but otherwise he will have a blind approach over the hill and will probably have to be satisfied with a six.â€

“The 13th (460 yards) (the 17th today) is a very fine hole which requires careful play and undoubtedly has proved many a golfers’ Waterloo. Two good wooden shots and a pitch to the green which is on the top of a rather steep hill is all that is needed; but a creek catches a bad second and a poor approach breeds trouble. A player who writes five on his card should be well satisfied.â€

He finishes his story by noting, “It is probably that as time goes on a few trees will be removed in one or two places where the course is somewhat narrow…However, where the whole is so good it is needless to pick flaws. In the phraseology of the hoi poloi, the Homewood golf course is ‘sure some golf.’â€

It is interesting that talk of tree removal was being discussed way back in 1909!

Flossmoor Country Club Hole Routing and Yardages Over the Years

| Original | 1901 | 1909 | 1915 | 1923 | 2009 | 2009 | |

| Routing | Reroute | Blue | White | ||||

| 16 | 550 | 535 | 1 | 518 | 499 | 488 | |

| 17 | 370 | 340 | 2 | 212 | 213 | 195 | |

| 18 | 280 | 280 | 3 | 552 | 434 | 420 | |

| 1 | 285 | 280 | 4 | 342 | 331 | 319 | |

| 2 | 570 | 540 | 5 | 447 | 445 | 431 | |

| 3 | 350 | 315 | 6 | 417 | 434 | 422 | |

| 7 | 126 | 173 | 161 | ||||

| 4 | 325 | 330 | 8 | 335 | 461 | 417 | |

| 5 | 410 | 375 | 9 | 387 | 626 | 560 | |

| 6 | 500 | 475 | 10 | 490 | 553 | 522 | |

| 7 | 140 | 140 | 11 | 178 | 187 | 173 | |

| 8 | 450 | 460 | 12 | 482 | 417 | 408 | |

| 9 | 130 | 90 | 13 | 116 | 135 | 122 | |

| 10 | 250 | 270 | 14 | 338 | 366 | 334 | |

| 11 | 430 | 426 | 15 | 444 | 431 | 424 | |

| 12 | 310 | 350 | 16 | 357 | 425 | 402 | |

| 13 | 390 | 460 | 17 | 463 | 473 | 461 | |

| 14 | 130 | 150 | |||||

| 15 | 240 | 325 | 18 | 497 | 533 | 505 | |

| Front | 3160 | 3005 | 3336 | 3616 | 3413 | ||

| Back | 2950 | 3136 | 3365 | 3520 | 3351 | ||

| Total | 6110 | 6141 | 6701 | 7136 | 6764 | ||

The original course started at what is now hole #4. Hole #7 did not exist until the rerouting that occurred after the second clubhouse fire in 1914. Also at the time of the rerouting, holes #14 and #15 from the original design were combined into today’s 18th hole.

How the Renovation Came About / Master Plan and the Membership

The renovation program was completed over three seasons. Each year, basically six holes were put under the knife starting just after Labor Day with the intention that most of the work would be completed by Memorial Day. Since Flossmoor only has 18 holes, the membership was not interested in having all of the work done at once, as that would have required the course to be closed for a significant period of time. By doing the work in phases, the membership was able to play the majority of the course throughout the project. In fact, there were only rare instances that less than 17 of the 18 holes were available for play. The club’s contractor, Country Golf, was an excellent partner during construction and made every effort to avoid significant hole closings for any lengthy period of time.

During the first year, holes 14-18 were renovated, and the planning for hole 13 (one of the two totally rebuilt holes) began. The second year, holes 7-12, plus the completion of hole 13, took place. Hole 8 was also totally redesigned. Beginning in the fall of 2008, holes 1-6 were renovated, and the project came to completion in the spring of 2009.

The most difficult part of the project was educating the membership on the need for the significant tree removal around the course. Hearn stressed the need to bring back the strategic angles of play to the holes. Mark Egge, the club’s greens chairman, brought in a number of noted arborists (including one from the world famous Morton Arboretum), to discuss the need to deal with the over planting that had occurred at Flossmoor. Finally, Bradley Klein, from Golfweek, was brought in to do a presentation to the membership on tree management. The research and education effort paid off, as the membership began to embrace the changes that were taking place.

Here is what Hearn, Lively, Egge, and Director of Golf, Trey Robbins, had to say about the project, in their own words.

A Conversation with The Architect, Raymond Hearn

How would you describe your style as a golf course architect?

Hearn: First of all, I would classify myself as a “lay of the land†architect, meaning I start by looking at what the particular piece of property offers me. If the project is a restoration, like Flossmoor CC, I look to see what the original design intent was. Is the original routing still intact? How are the green complexes, which I believe are the heart and soul of a great golf course? I also believe in detailed design drawing coupled with many site visits. I have been to Flossmoor in excess of 50 times during the project’s lifecycle, from pre-planning, design, and construction. Field changes are always necessary. I liken them to the final paintbrush strokes on the canvas.

How many original designs and renovations/restorations have you completed to date?

Hearn: I have completed 32 new courses so far in my 23-year career and have worked on over 115 renovation/remodeling projects.

When considering classical or modern architects, who do you consider yourself most similar to?

Hearn: From the classical era, I think that I come closest to emulating Alister MacKenzie. As a true frugal Scotsman, he engrossed himself into each design, especially for his work in America. He was a minimalist who would work to find ways to incorporate his design onto the existing terrain. As far as modern architects go, I would have to say Tom Doak, as I consider him the modern day MacKenzie.

What was your first impression of FCC and what did you feel needed to be addressed first?

Hearn: I felt the incredible history and tradition of the club which had been preserved for over 100 years. I thought that the routing was good, the majority of which dated back to the original Tweedie design. I thought that the green complexes were outstanding. The most significant weakness of the course was the bunker design. I felt that going back to a Thomas-style golden age design would suit the course much better. I also wanted to bring back the risk/reward options that had been impacted by the advancing technology of today’s balls and clubs. In the end, these changes would give the course a strong visual upgrade.

What was the most challenging issue you faced during the project?

Hearn: I thought long and hard about how to integrate the pond into the redesign of hole number 8. The old design had an artificially raised green that looked like a field goal between the two ponds. I worked to make the hole lower profile and incorporated a risk/reward feature with the green’s location in proximity to the right pond. I also left a bump and run option on the left to keep the ground play available as can be found on all of the other holes on the course.

Were there other issues that needed to be considered for your design?

Hearn: As with many parkland courses, there were tree management issues that had to be addressed. There were locations on the course where tree canopies were having a detrimental impact on the courses agronomy. Many of the great long views on the course had been lost. Some fairway edges had been lost and many strategic options were gone. The only play option on some of the holes was to hit the ball directly down the center line of the fairway due to the tree canopies crowding out all of the other play angles. The tree removal program helped to address these issues in a significant way. I also feel that the reintroduction of the prairie grasses on the front nine on holes two, three and four helps to bring the course back closer to its roots.

Was the project completed as you envisioned and would you have done anything differently?

Hearn: I am very pleased with the final outcome. The necessary adjustments from the design plans were incorporated as field changes as the project went along. I worked closely with the club’s project committee all the way from concept to design to the fieldwork.

What other projects are you currently working on?

Hearn: Overseas, I am working in South Korea on Doomi CC and on Domaine de Lavagnac in France. In the U.S., Moonbrook CC in New Jersey is a current restoration project and I have begun working on a great sandy site in Biloxi, Mississippi where almost no earthwork other than the green complexes will be required.

Where does the Flossmoor project stand in the body of your work?

Hearn: It is definitely the plum project out of all of my renovation/restoration work, and as far as the course goes, it should stand on its own with the top courses in the country.

A Conversation with Greens Chairman, Mark Egge, Superintendent, Robert Lively, and Director of Golf, Trey Robbins

How did the renovation/restoration project at Flossmoor begin?

Egge: The real genesis of the project was the need for a comprehensive tree program. The willow trees along the 18th fairway had become a real problem from both a maintenance and turf quality perspective. The Board was concerned though that just cutting them down without a plan on how to redesign the 18th hole was shortsighted. We brought in tree consultants from Morton Arboretum, the USGA, and a professional arborist for ideas. We then thought that we should have an architect of record to help redesign 18 and for other future changes on the course.

Lively: The need for a master plan and an architect of record was very important so that all future changes would be consistent with the plan. I found Ray Hearn in On Course magazine. He had written an article on tree planting programs at private clubs and the problems those programs had caused to turf conditions and course quality. Ray was a lay of the land guy, and he was brought in to redesign the 18th hole without the willows. Ray’s plan was presented to the board and membership and was approved. A new renovation committee was then formed that was separate and distinct from the greens committee. Each hole was reviewed and all changes were subject to a unanimous committee vote. Additionally, Hearn had to agree with all changes.

What were the original goals of the plan from your perspective?

Egge: The goal was to get a comprehensive, cohesive design from a single architect that worked with Flossmoor’s style and history. We are a 110 year old classic course and needed an architect that understood what that meant.

Lively: I was most concerned with preserving the course’s basic layout and not making wholesale changes. The major objectives were to make the game more enjoyable for the all players, to deal with technological improvements of the modern clubs and balls and to improve the strategic options around the golf course.

Robbins: I wanted to see the club move toward having a blueprint for the future that would maintain and preserve the style and design of the original course. I didn’t want to see us become a club where the direction of the course would change with each new greens chair. The plan now requires that all future changes must go through the architect of record.

What do you feel were the most critical events of the project? How did they lead to the successful outcome?

Lively: From my perspective, the tree removal program was the most significant part of the project. The courses turf quality has improved dramatically as a result. Also, the field changes that were made during the construction improved the original plan in a number of ways. Overall, the outstanding plans created by Hearn coupled with his numerous site visits were a key to our success.

Egge: The membership came together to support the project after many presentations of the details. The capital program that funded the work was critical to the success of the project, and the members’ overwhelming support of that plan was vital.

Robbins: The fact that we were able to keep the course open throughout the project’s three phases was very important. Our construction contractor, Country Golf, worked very closely with the club so that communications could go out to the members to alert them on any potential impacts on play.

What most challenging issues were faced during the project?

Lively: Undoubtedly, the weather that we faced over the three construction seasons. For example, the first year was very poor with heavy rain. This forced us to actually improve the drainage plan on the back nine, which sits in a flood plain.

What are you most proud of now that the project has reached completion?

Robbins: The impression that the course now leaves with the members’ guests. It is very rewarding to the staff and the members alike to hear all of the positive comments. The golf experience is so much better. The course is very challenging, and the conditions are excellent. This was the most significant renovation I have seen at the courses I’ve been at. The changes were profound but the plan did an excellent job in keeping the underlying feel of the course intact.

Lively: We now have a course that’s easier to maintain, the drainage is so much better, the turf quality around the course and on greens and surrounds has improved in many places. The addition of the new tees has added to the enjoyment and playablility for all levels of golfers. Also, I no longer have to hear ‘what a nice course, but hole 13 is hokey’. It has also been extremely rewarding to be a part of a project like this. Not every superintendent gets the opportunity to do this in his career. We just improved an already great golf course.

Egge: I am so proud of the members who voted with their money and supported the club like they always have.

If you could change anything about the project, what would it be?

Robbins: I just wish we would have done it sooner!

What advice would you give to your peers at other courses considering embarking on a renovation/restoration project?

Egge: Do as much research as possible. Seek out experts. Require the architect to review all changes and make sure that in the end the architect supports all of the plan.

Lively: Hire a qualified architect that fits the club’s style and listen to what he says.

If you were speaking with someone with no knowledge of Flossmoor Country Club, what would you tell them?

Lively: Come out and experience it. The course will speak for itself.

What do you think the future holds for Flossmoor Country Club?

Robbins: First, we should take the time to enjoy the new course. We should also make an effort to host events again and support amateur golf. Flossmoor has hosted 15 major amateur events in its history and that tradition should continue. For example, we are very excited to have been selected to host the 2014 Western Junior Amateur.

Any closing thoughts?

Egge: I can’t thank the hard work and dedication of true professionals like Ray Hearn, Bob Lively, and Trey Robbins enough. The renovation committee put in many hours of work on this project which was a critical part of its ultimate success. And again, without the support of a great group of members, this would not have been possible. I hope everyone enjoys the experience.

This is the artist rendering that was created from the master plan of Ray Hearn that inspired the the club membership to proceed with the renovation project.

The Holes – Before and After

Hole 1 – Road

This hole utilizes the area of Hole #16 on Tweedie’s original design and was named for the railroad that once paralleled one side of the hole. This hole plays as a short par 5, although the position of the bunkering on this hole in the green’s approach area makes it very difficult to reach the green in two. The fairway bunkers have been redesigned to be aligned perpendicular to the line of play vs. parallel for added emphasis, challenge, and strategy. The layout of the bunkers allows numerous playing options on this hole. Attacking the green in two shots allows for an eagle or birdie opportunity. The green’s varying slopes create a demand for accurate putting.

Hole 2 – Gate

This hole was named for a gate off Western Avenue used to access the old clubhouse location. The key to scoring on this hole is to attack the pin via aerial shot or a low bump and run shot. A new bunker short of the approach was added to heighten the accomplishment of a well executed bump and run shot into the firm approach. Cupping areas nearest the adjacent bunkers requires added strategy and thought. In order to heighten the strategy of attacking the new cupping area in the back left of the green, a new expanded bent grass collar “catch area†has been added. If a shot falls down the slope to this area they will be left with three options for your recovery back to the green; lob, pitch, or putt.

Significant tree removal was done at both the teeing area as well as down the fairway on number two…

Hole 3 – Home

This hole was named “Home†as it was originally the 18th Hole. It is a classic hole in terms of strategy and aesthetic appeal. A key to low scoring on this hole is to try and carry the creek. Originally being a par 5 the green was designed with aggressive and varying slopes necessary to challenge a 9-iron or wedge on third shots. As a long par 4, many golfers need a mid to long iron into the green that is less receptive to those iron shots. The back right corner of the green offers a tournament cupping area and a more strategic relationship with the adjacent bunker. There remains a bump and run area into the demanding green.

New bunkering, a large new collection area right of the green, significant tree removal, as well as the introduction of new prairie grasses were part of the work on hole three.

Hole 4 – Widow

This hole utilizes the area that was originally Hole #1 on Tweedie’s original design and was named “Widow†which seems appropriate since golf widowhood begins on hole 1. There are six viable options in attacking the landing area from the tee. All three bunkers were remolded for increased classical appearance and deepened for increased challenge. For increased strategy, the back right corner of the green was restored in order to create a tournament cupping area and a more strategic relationship with the adjacent bunker. To set up for a birdie opportunity, select the desired landing zone and avoid the bunkers in that specific area. The longer drive sets you up for a short lob shot into a very challenging green.

An entirely new bunkering pattern was introduced down the fourth fairway. New prairie grasses are also being introduced right of the fairway.

Hole 5 – Spring

This hole utilizes the area that was originally Hole #2 on Tweedie’s original design named “Springâ€. The name suggests beginning or early stage of a round according to Club Historians. This long par four has beauty, strategy, and challenge. The key to scoring on this hole is to avoid the repositioned bunker on the left side of the hole with the drive, which leaves a preferred “bump and run†avenue for the second shot into the green. The bunker guarding the right front corner of the green adds strategy and challenge when approaching the front right pin placement.

Hole 6 – Neuk

This hole utilizes a portion of the area that was Hole #3 on Tweedie’s original design named “Neukâ€. Neuk is Scottish for nook, an angular portion of land. Bobby Jones coined this hole the “difficult sixthâ€. The key to scoring on this hole is accuracy on the drive and second shot. The landing area is narrow and tucked “tightly†between a massive oak grove guarding the right side of the hole and OB on the left side of the hole. The green complex is among the best at Flossmoor in terms of subtle slopes and challenging cupping areas. A par on this hole is a good score.

Hole 7 – Gucks

This hole was not part of Tweedie’s original design. According to Club Historians, Guck in German means glimpse or glance. Bobby Jones pays great respect to this short but challenging par 3 in his book Down the Fairway describing the hole as another disastrous mashie-niblick hole†(a 7-iron today, and one of very few shots that Jones confesses he never mastered). Jones stated that this hole contributed to costing him the National Amateur Championship to Max Marston in 1923. The green area features a front bunker and extended bent grass approach to the pond’s edge. Players ending up in the new collar area will now have a choice of chipping, putting or lobbing a shot back to the pin.

A new chipping area was added around the sides and rear of the green along with extensive tree removal.

Hole 8 – Lane

This hole utilizes a portion of the area that was originally Hole #4 on Tweedie’s original design named “Laneâ€. The name suggests a narrow passage between the mighty Oak Trees as viewed from the back tees. Players can choose one of four new tees, which were built in order to increase the overall length of this hole and to provide a variety of playing options for players of varying skill levels. There are several ways to approach this green beginning with a fade to the left approach allowing a shot to feed down left to right from the slight slope onto the green. When the pin is placed behind the pond, a lofted medium iron will be necessary to have a shot at par or birdie.

Number eight was entirely rebuilt during the renovation. The old green was artificially pushed up (unlike the other greens on the course) and positioned between two ponds.

Hole 9 – Oak

This hole utilizes the area that was originally Hole #5 (second half of the hole) on Tweedie’s original design. The hole is named “Oak†for the oak grove that exists left of the hole. This hole is a good test of golf and a good finish to the front nine. The key to scoring on this hole is maximizing your drive and second shot distance then honing in with precision to a very demanding green complex. An expansive collar left of the green allows the player multiple recovery scenarios back to the green. The green has been expanded front left in order to add more emphasis to a front left pin. Birdies are well deserved on this demanding par 5.

Major tree removal and reshaping of the fairway were some of the highlights on hole nine. Additional tree removal was done around the green and a new chipping area was added.

Hole 10 – Glade

This hole utilizes the area that was originally Hole #6. This hole is named “Gladeâ€, Scottish for an open passage through woods. There are three choices on the tee. The first would be to avoid all the hazards and lay up in front of the right fairway bunker leaving a fairway wood to a second landing area. The second option would be to position a drive short of the bunker on the left side of the hole leaving a mid iron lay up or a big fairway wood to reach the green in two. The final option is to work a long draw off the tee past the right bunker. This leaves a fairway wood or long iron into the green. The green is very demanding and slopes from back to front and off on the sides.

Hole 11 – Spion Kop

This hole was Hole #7 on Tweedie’s original design. The hole is named after a hill in Natal, South Africa, where the British were defeated by the Boers in January 1900. In order to allow for a bump and run shot into the green, an approach bunker was removed and the green’s collar was expanded in front. The key to the tee shot is to avoid the two back left bunkers. The bunkers were expanded, by approximately six feet into the green, to develop a more challenging spatial relationship with the pin placements on the left side of the green. This uphill par 3 provides excellent contrast to the other par 3’s at Flossmoor and is one of the best in Chicagoland.

The tough 11th saw the removal of many trees and the left greenside bunkers were brought into closer proximity to the putting surface.

Hole 12 – Tugela

This hole was Hole #8 on Tweedie’s original layout. Tugela is the name of a river in Natal, South Africa flowing alongside the Spion Kop. This hole is challenging due to the hill that begins 257 yards from the back tee and elevates 27 feet from Butterfield Creek. A blind second shot into this green must be carefully played as the green falls away from front to back. Harry Collis, golf professional and superintendent, probably added the “Chocolate Drop†mounds surrounding the green around 1917. This is also when the holes were renumbered to accommodate the new centrally located clubhouse. This is a very challenging par four.

Some tree removal and bunker work was completed on the 12th, as well as integrating the greenside mounds more closely to the putting surface.

Hole 13 – Easy

This hole was Hole #9 on Tweedie’s original design. The name was probably derived from the perceived low degree of challenge, which was probably never the case due to the 5 – 13% slope on the original green. The hole is now located adjacent to the original hole. A small green of approximately 5,500 square feet has challenging but manageable slopes “fingering†through the green. Pin placements are numerous throughout this new green. A low fade shot can be worked into various pin locations or attacked via a high lofted short iron. Three bunkers surrounding the green entrance challenge back right and front right pin locations. A generous collar left of the green catches errant shots leaving you multiple recovery options back to the pin.

Hole 14 – Glen

This hole was Hole #10 on Tweedie’s original design. The name “Glen†means a secluded narrow valley in Scotland. A new tee north of the creek added 30 yards in length to the hole from the back tee and the tree clearings on the right of the hole added a double fairway around a majestic 60-foot tall white oak. From the back three tees, the player now has three options. A fade or draw can be played around the oak or longer hitters can go over the oak. A new bunker off the left defines the fairway. The green complex was reduced by about 10% with the elimination of a portion of green on the right side. This portion of the green was replaced with collar allowing multiple recovery options back to the green.

Two new teeing areas were added to the north of the original tees and tree clearing added a new play option to the right of the large oak in the 14th fairway.

Hole 15 – Orchard

This hole was Hole #11 on Tweedie’s original design. The name “Orchard†is a fitting name for an orchard that existed along Western Avenue around 1900. The key to this hole is a drive down the right side avoiding four new grassy hollows on the left. The second of these hollows pushes into the fairway narrowing the primary landing area to 50 feet. A new bunker was added in the front left corner of the green. The green was expanded in the front right and back right adding several challenging new pin placements. There is a collection area for stray shots on the back right of the green. Birdies will be rare on this hole.

Tree removal and some added green space were the major changes to number 15, always one of the strongest holes on the course.

Hole 16 – Braeside

This hole was Hole #12 on Tweedie’s original design. “Braeside†means hillside in

Scottish. The new and very strategic bunker added along the right side of the hole creates three driving options; short right, left, or long right. The left option is new as the fairway now connects with the #17 fairway creating a long grand view of holes 16, 17, and 18 as seen from the clubhouse. The drive options chosen will account for a 40-60 yard difference for your second shot. The bunker in front of the green named Eleanor’s Teeth is to be avoided at all costs. A significant collar area was added back right of the green. This new collar allows shots to feed off the existing hill onto the green. The green exhibits a strong right to left slope.

…which were removed during the renovation. Also, its fairway was connected to the 17th and 18th creating a grand lawn behind the clubhouse.

Hole 17 – Haugh

This hole was Hole #13 on Tweedie’s original design as is still regarded as one of the Chicago Area’s most challenging golf holes. The hole is named “Haugh†for a low-lying meadow by a riverside. According to the Tradition Endures, the green sits atop the hill where an old horse barn used to stand. The key to this hole is a long drive down the right side of the fairway. A bent grass approach can be utilized as a new “bump and run†avenue into the green. George O’Neil, an accomplished amateur, honored this hole in September 1918 as one of the region’s most challenging golf holes. There are not many par 4s that will rival this hole’s appeal and challenge. Par on this hole will feel like a birdie.

Hole 18 – Farm

This hole was created by combing holes #14 and #15 from Tweedie’s original design. The name “Farm†signifies that this specific area of the course was a farm at one time. The first obstacle is to avoid the three new fairway bunkers. The first two bunkers come into play from the tee. Three bunkers guard the narrow second landing area and three bunkers guard the green. The key to scoring on this finishing hole is based on the success of the second shot. Options range from laying-up with a mid-to-long iron or going for the green with two magnifi- cent shots. The green complex has challenging slope. Bent grass runs from behind the green all the way to the clubhouse.

All of the willow trees along 18 were removed, and a series of three sets of three bunkers were strategically positioned along the fairway and green.

Historic Aerials

This is the earliest aerial image of Flossmoor Country Club from 1938. Note the absence of the subdivision in the lower left corner of the photo. This is the area where holes 17 and 18 were located in Tweedie’s original design. Those holes were later remodeled by Willie Watson, with the par 3 second running back south (right on the aerial) and the par 5 third heading back north (which was the 18th hole up until 1915). Also by this time, the auxiliary nine hole course had disappeared. One can see the lack of trees on the majority of the property, other than for the forested areas in the middle of the photo. The par 4 eighth hole was straight and ran diagonally in the left third of the photo, and hole nine was a par 4 heading back south.

By the time of the 1974 aerial, it is apparent that a tree planting program had begun at Flossmoor. Note a series of trees lining almost all of the holes on both the front and back nines. The basic routing of the course is virtually unchanged from the 1938 photo. A subdivision is now located in the lower left hand corner of the aerial.

By 2002, a number of major changes had occurred at Flossmoor. During the 1980s, the eighth hole in the middle left third of the photo had become a dogleg right and two ponds had been added, one on each side of the green. Hole three had been shortened into the very difficult par 4 its is today, and hole nine had been lengthened into a demanding par 5. This was done to accommodate a longer driving range in the center of the property. The property between holes three, four, and five had become a more natural wetland area, and a short game practice facility had been added right of the sixth tee as well. The trees on the property had continued to mature in many areas. A number of bunkers had been added and many had been reshaped.

The final aerial was taken in early July, 2009 and includes all of the design changes the club has incorporated over the last three years. The reshaped and repositioned bunkers can be observed throughout the course along with the results of the club’s significant tree removal program. The new eighth and thirteenth holes are viewable as well as the grand fairway connecting holes sixteen, seventeen, and eighteen.

The Completion of the Project

The project came to its finale on July 31, 2009 when the club hosted a National Media Day. The day was chosen specifically to coincide with the 100th anniversary (to the day) of Chick Evans’ first national title, which was the 1909 Western Amateur at Flossmoor (then Homewood) Country Club. The club combined that day with a fundraiser for the Evans Scholars, the great caddie scholarship program that was founded by Evans in Chicago.

The most rewarding part of the project has been reached, as the membership is now able to enjoy the culmination of the three and one-half years of work on the course.

The End