Computer Assisted Golf Course Design

by Jeremy Glenn

It may seem brazen to discuss computers and their influence on golf course architecture on a web-site seemingly so openly devoted to any and all things traditional. However, such a discussion may allow us to look upon this long misunderstood tool in a different way.

At first thought, computers certainly would seem to be quite at odds with the cherished qualities found in the raw and unique landscapes of the world’s best golf courses. Or, to paraphrase Winston Churchill’s description of the game of golf – but in regards to the use of computers in the field of golf course architecture – these machines certainly seem to be ‘tools ill-suited for the purpose’.

Yet rather than fall victim to the oft-repeated myths surrounding the use of computers in golf course design, we should instead take a closer look at this subject, perhaps in the hopes of drop-kicking some of these myths the way of the orange-coloured golf ball.

What myths are we talking about, then?

Well, they’re not so much myths as they are mis-understandings, or not-understandings-at-all. Specifically – and what it really boils down to – many assume that Computer Assisted Design (from which is derived the infamous acronym CAD) really means Computer Designed. In other words, that the design becomes more a product of the computer and less one of the individual. Thankfully, that is no truer than a drawing being a result of the pen rather than of the artist. As of today, computers are still incapable of designing a bunker.

But this is where the comparisons of computers to a pen should end, because a computer can accomplish the following two main tasks, while a pen can only do parts of the first. They are:

1- Drawing things.

2- Drawing conclusions about those things.

Let’s look at each of these two important items separately.

1- Drawing things

Ironically, probably the seed of one of the many computer related myths is the fact that computers will straight-line you to death. These machines, when told, will draw a line from the infamous point A to its always-second-fiddle-cousin point B with ruthless speed and, literally, mathematical accuracy. And straight lines are not the only trick they can do. The can draw circles too. As well as squares, pentagons, arcs, or any other geometric shape you can imagine. These are all done with mathematical accuracy. Tell it to draw a circle that’s 5 metres in diameter, and that’s what you get. You won’t ever see the computer sneeze it the middle of an operation and draw up a circle that 5.000000000001 meters in diameter. Never. Always perfect. The perfect draftsman. Draw a triangle from A to B to C and back to A again, and it will hit those points on the button time-and-time again. I don’t care how much you want to zoom in to see if it missed its mark by a zillionth of a millimetre. Go ahead, I’ll wait. Zoom-in until you can see the electrons flying around the atom core, and then you’ll see that the (perfectly straight) line has arrived smack at the centre of that core.

Now this is great stuff, and can make drawing such things as roads and residential development a breeze. But as we all know, golf courses – quite thankfully – don’t have geometric shapes or straight lines. And golf course features are not aircraft engines: they don’t need to be designed with microscopic accuracy.

Fortunately, computers can also free-hand you to death. Or, more accurately, they can ‘graceful-curve’ you to death. But that is, of course, the seed of another computer-related myth: a course that is so-called ‘Computer Designed’ will be an orgy of nothing but graceful curves – save perhaps a few geometric figures – with little variety in the resulting shapes of the course’s features and certainly nothing rugged or truly natural-looking.

So, let me emphasize that a computer will show a ‘graceful-curve’ only if you draw it yourself. It is in no way predisposed to do so. It will help you draw anything you want. If you want to draw a rugged bunker edge, for example, it will help you there as well. In fact, you can literally ‘free-hand’ a drawing, moving your mouse around your screen as you would a pen, and that’s what the computer will show.

However, ‘free-handing’, for me at least, is still much easier to do with the old pen and paper. That’s not the computer’s fault though, just a personal preference as a result of habit. Perhaps our children will be more comfortable with a mouse in their hand instead of a pen. And that’s fine. But for me, being born before the age of personal computers, nothing can substitute the all-important and old-friend feel of a pen in my hand. A hand-drawn plan, while perhaps not as accurate or ‘perfect’, certainly has a much warmer and artistic look to it. Computer plans can sometimes appear ‘cold’ and ‘aloof’, especially when they aren’t very detailed. Incidentally, that is why, in our office, we never actually design a golf course directly on the computer. We always do that by hand. The computer is only used to draw-up the final design, to clean it up and to make it look really sharp. Basically, we draw the design by hand, scan-in whatever sketch that may be, and then digitize that sketch into the final construction or presentation plan.

To open a little sidebar here, there is a difference between ‘scanning’ and ‘digitizing’. A scan is basically an image, nothing more. It’s a picture. Digitizing, on the other hand, involves drawing a plan on-screen and telling the computer what each line represents. It’s alot more work, but the digitized drawing truly becomes ‘workable’ for calculations or editing.

Where the computer starts to shine – at least with AutoCAD – is in the flexibility it offers, through the use of features like Layers, Viewports, Paper Space and Model Space, amongst many, many others. Essentially, it becomes very powerful in manipulating a drawing. For example, you can draw the golf course greens and tees on one Layer, contour lines on another, drainage pipes on a third, plantings on a fourth, etc… You can then add, remove or combine these Layers – which can be compared to sheets of see-through paper – to show or highlight different elements in different ways in various Viewports, allowing you to print any sort of plan you want, at any scale, showing any information you deem relevant. All this from the same file and drawing. A grading plan, grassing plan, drainage plan, or irrigation plan can each be seen and printed with a single click of the mouse.

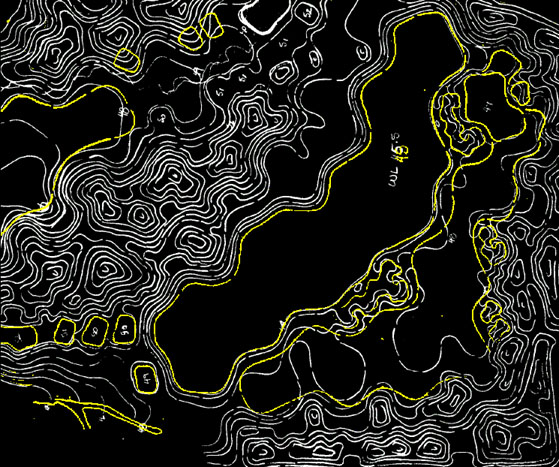

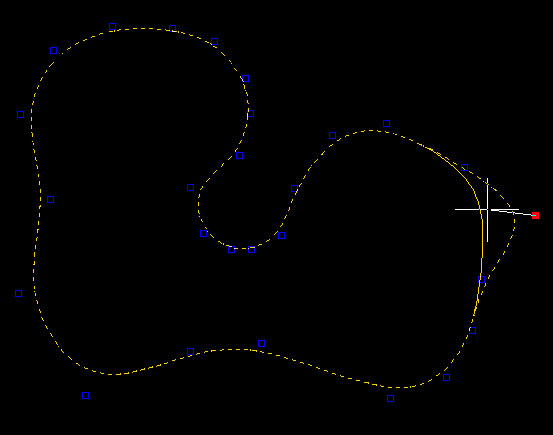

The initial ideas, drawn by hand. A lot of information (such as cart paths, drainage, plantings) is left out. It will be added on later, once we know nothing else will change. The tees on the top-left corner, as you can see, were already to be relocated.

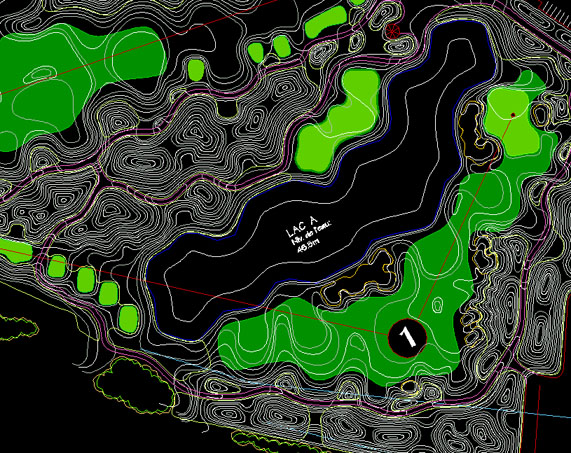

What is shown on-screen, once the initial sketch has been digitized and additional details have been added. Notice how the water level has ‘risen’ by more than a metre (from 45 to 46.5), when we realised we were removing too much material from that area. And that little pot bunker underneath the ‘1’ was added when, after seeing a 3D simulation, we felt there was something missing, visually, on that side of the hole.

One of the final plans, as printed out. This one includes contour lines and grassing information, as well as the existing contours in light gray.

And, of course, you can e-mail CAD drawings. Send it off to the printers over the Internet, ready to be picked up after work. Or send it to the environmental-engineer for her to input some wetland protection criteria, after which she just zips it back to you.

Another great advantage with computers and how they manipulate drawings is the ease in which you can ‘tweak’ things. Say you’re drawing a bunker, and you don’t like the shape of what you just drew. Rather than erasing and starting over, you can ‘select’ the bunker, and then mold, tweak, and basically fiddle around with the line until you’re perfectly happy with the result. Or, if you like the shape, but the bunker is a bit too big or too small, you simply scale it up or down to the desired square-footage. Or you rotate it around slightly to enhance the angle of approach or the way it fits into the existing slope. Or you move it around as little or as much as you want to keep it far enough away from a tee, for example.

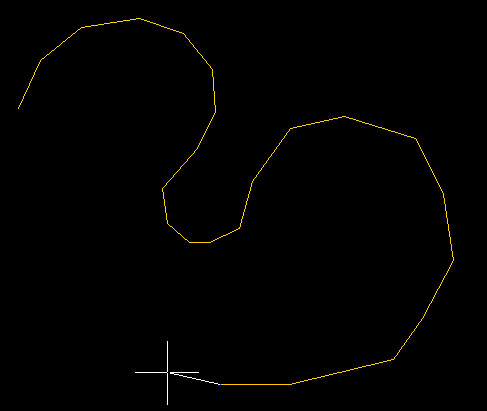

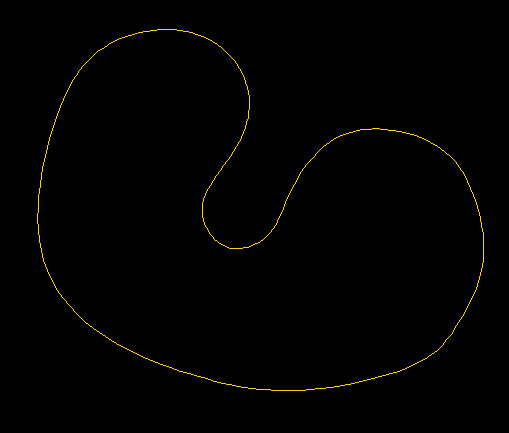

First you draw the bunker…

…then you smooth the line…

…then you fiddle around with the final shape.

Basically, changing and editing is far easier to do on a computer.

That’s because modifying drawings done by hand is a royal pain. I mean, it really, really, is a pain in the derrière, if you’ll pardon my French. First you should make a photocopy of the original, for your records. Then you start to erase, which is always a messy, time-consuming job. And try as you might, you always end up erasing things that you didn’t want to erase (existing contour lines, for example). Then, of course, you need to re-draw, trying to make the new lines blend in with the old lines, all this on a messed-up sheet of film that is probably a third generation photocopy anyway.

Of course, if you’re really unlucky, you end-up having to start the whole plan again.

Ugh!

Thankfully, computers put an end to all that. Modifying plans becomes much cleaner and faster. Basically, just make a backup, then hit ‘Delete’, and away you go. Yes, re-drawing is a bit of a pain even on the computer, but it sure beats doing it the old fashioned way.

Now, of course, another myth surrounding Computer Assisted Design is that by making it so easy to move and copy things around, architects that use CAD have become lazy and simply ‘copy and paste’ previous designs into new settings. While computers can make this an easier task – although, in truth, not that much easier – they can hardly be faulted for such unethical and lazy practices. Architects intent on acting this way can easily do so without a computer: it is just as easy to slap a piece of trace paper on a previous design and copy away.

And it is certainly not as if green or bunker shapes are taken for a bank of pre-fabricated ‘Computer Designed’ features and simply plastered into place indiscriminately, Ã la cookie-cutter. Quite the contrary, each bunker, tee, green is designed and drawn individually to fit into its unique setting. Just like the way it is done with the ol’ pen and paper.

The computer is a tool to help you draw anything you want, and it will do so with irreproachable speed and accuracy, and with great flexibility. Of course, sometimes the computer is the right tool for the job, and sometimes it isn’t. In fact, we often combine computer and hand on many plans. For example, we’d print a plan with site features such as contour lines or property limits, along with plan information such as titles, dates, scales, company names, etc… We can even insert a soft aerial picture of the property as a faded background. This base is then printed out as many times as necessary and we’d draw various routing options or concept drawings, by hand, overtop of it.

It is without a doubt an extremely powerful and versatile drawing tool to have at our disposal.

2- Drawing conclusions about those things.

Now, as much as computer can help you in drawing – and re-drawing – your plans, the computing power of softwares such as AutoCAD, Microstation, or Terra Model, render the pen and paper virtually obsolete.

A fair-sized chunk of time in the life of a golf course architect is spent calculating areas and volumes: How much seed-mix? How much topsoil? How much earthmoving? Letting a computer help you in this often mind-numbing task allows you to have more accurate numbers in a fraction of the time, and to have more confidence in those numbers – thereby allowing you to spend more time actually designing the golf holes, or flirting with the waitress at the bar&grill next door.

Actually, calculating areas by hand is a fairly simple task, and when using a planimetre – a little electronic device that you run around the perimeter of a feature – can be done fairly quickly and accurately. Computers, on the other hand, will also calculate earthwork quantities. That is an extremely important task, and a very difficult and tedious one to do by hand with any accuracy.

Essentially by comparing the existing contours with the proposed contours, softwares such as Terra Model will calculate, in a few seconds and down to the teaspoon, earthmoving volumes for a bunker, a green, a lake, a full golf hole, or even the entire site – and all this with or without ‘swell and shrink factors’. Doing those numbers by hand, for a single golf hole, would easily take a full day. It will tell you how much you’re cutting, filling, where you are doing so, and how much and where you need to dig or fill in order to meet those numbers. It can give you a 3-D simulation of the existing topography, of the proposed topography, and of the cut&fill operation. You can therefore visualise, before a single tree is cut, whether or not the creek will be visible from the back tee, or if the green-side bunker can really be seen from the left side of the landing area, or even by how many feet you need to shave the hillside so that you can see the landing area from the tee.

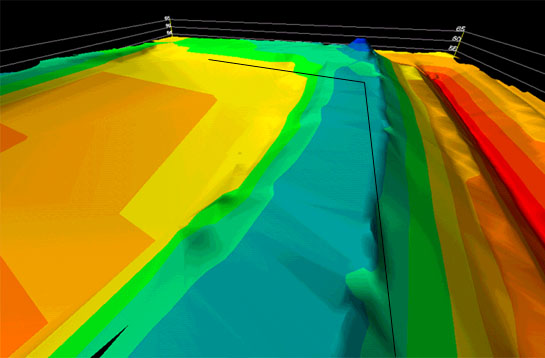

The ‘before’ view, of the existing topography where the first hole is to be built. It’s a man-made crater serving as a dump. The approximate location of the centre-line is also shown.

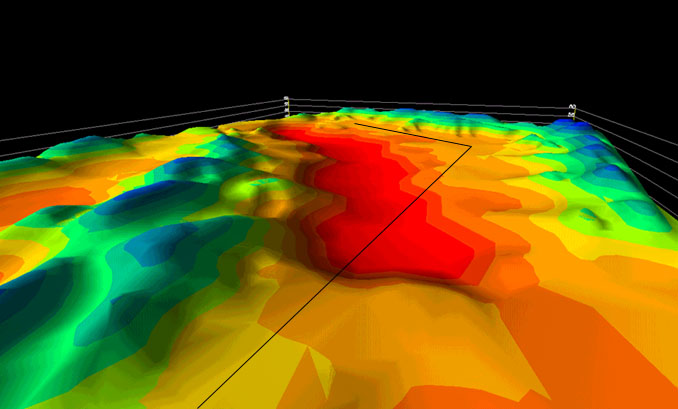

The ‘after’ view. The 1.5x vertical exaggeration shows how much the topography has changed. Roughly 300,000 cu.m. is to be removed from the dump area, and will be used to build the rest of the golf course, which sits in low-lying areas. You can even see the little pocket where that pot-bunker was finally added.

Computers can help you with a myriad of other tasks, simple or complex. They will help you to understand future drainage patterns. They can show what will drain where, and how big a pipe you need to evacuate the water. They can assist you in designing irrigation system for optimal cost and water distribution, tell you how much bedrock you will need to blast, show you optimal routes for transportation of material, or quickly and graphically illustrate percentage of slope, before and after construction.

This is, for obvious reasons, a tremendous help. Golf course architects are not bound, in the field, to the nitty-gritty details of grading plans. Just because the plan says: ‘put a bunker here’ or ‘shape a swale there’ doesn’t mean those suggestions are to be followed blindly. However, architects are bound to overall earthmoving numbers and material quantities. Having as accurate an estimate as possible of those numbers is one of the most basic leveraging positions available to him during the construction process. In other words, earthmoving numbers and cut & fill plans let the architect know how much earth will be moved, and where it will be moved. What he does with that earth in the final shaping process is, of course, mostly field work, and is the art of golf course architecture. It is entirely unrelated to the use of computers in the planning stages of the design. I cannot stress this enough. It is absolutely impossible to look at two golf courses and tell which one had plans drawn by hand and which one was designed with the help of CAD. And using CAD does not in any way limit or impede on or ‘dumb down’ the artistic creativity of the architect. Computers have absolutely nothing to do with the creative process of designing golf courses. Computers don’t design golf courses. Humans do.

Last but not least, computers also have a number of other useful applications and softwares. PhotoShop and PageMaker, for example, are extremely powerful software, from which it is possible to create fully rendered Master Plans, colour documents, and just about anything else. Quite frequently, for example, we would print out a plan, render it, and then scan it. We then use PhotoShop to ‘touch-up’ the rendering: correcting mistakes, enhancing colours, softening transitions, to which we can add such items as logos, pictures or scorecard, before printing out the presentation plan, in full size and/or smaller versions to be distributed individually. And if the client calls us at the last minute telling us that the bunker on the left side of the third green was never built, it is easy to airbrush it away with a few strokes of the mouse, never to be seen again.

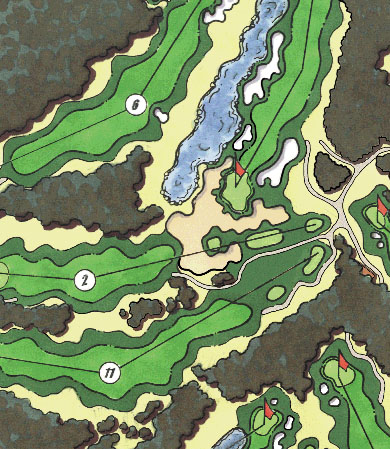

Parts of this rendered plan were drawn and coloured by hand. Other parts were drawn and rendered with PhotoShop. Can you tell which?

At any rate, this was just a brief overview of the influence and uses that computers have had on the field of golf course architecture. There are, of course, many more uses and situations where computers are helpful, from surveying the initial site with GPS, all the way to the laser-leveling of tees based on pre-set elevations. If golf course architecture is both art and science, then computers assist the architects in building a solid and secure technical foundation to their design, thereby allowing the art to soar to new heights.

Feel free to click on the following links for additional information on some of the software discussed here (no, this is not meant to be a shameless plug, just additional stuff for the curious amongst you…) :

AutoCAD: http://www.autocad.com

Terra Model: http://www.trimble.com/terramodel.html

PhotoShop: http://www.adobe.com/products/photoshop/main.html

PageMaker: http://www.adobe.com/products/pagemaker/main.html

Microstation: http://www2.bentley.com/products/default.cfm

The End