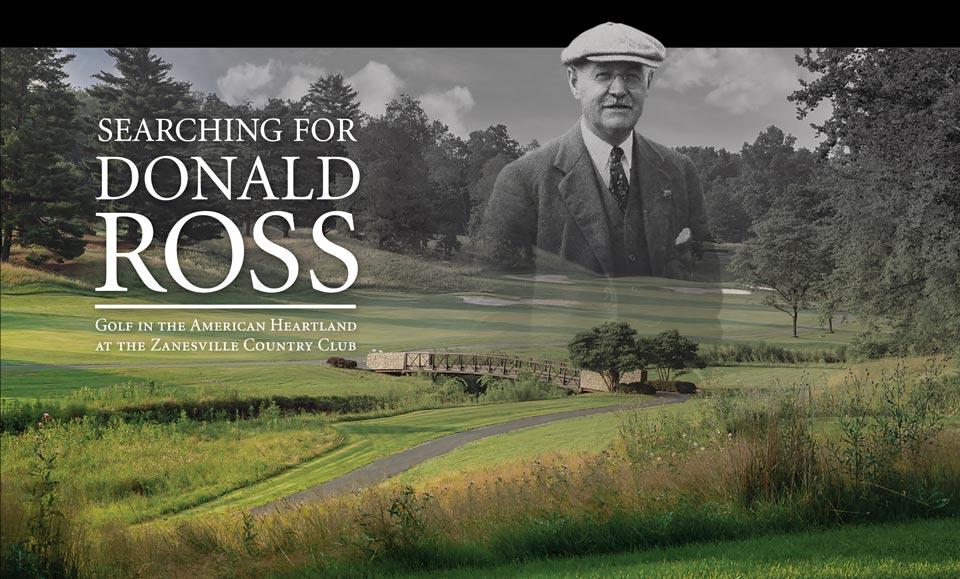

Searching for Donald Ross: Golf in the American Heartland at the Zanesville Country Club

Tell us what it was like growing up in Zanesville and what the Zanesville course means to the community.

Zanesville is a typical mid-western American small town. One of my earliest memories of the 1960s was watching my dad walk a few blocks to the factory where he helped make electrical transformers. Also, we lived across the street from a major tile manufacturer and we would go to sleep in the summertime, before AC, with our windows open to the sweet sounds of the tile manufacturing process. Today, both businesses, and their buildings, are gone.

The community has endured these and similar setbacks, like the decline of regional coal mining jobs, resulting in a very slight decline in population in the 1960s and the 1980s. However, we have rebounded economically and have steadily grown over the past forty years. We are optimistic about our future.

I feel confident that the community sees the Zanesville Country Club (ZCC) as both an asset and a point of pride. Next year we will host our fifth Ohio Amateur, the first in 1955 won by Zanesville native Bob Rankin over a field that included a 15-year-old Jack Nicklaus. Additionally, we have a robust junior golf program including hosting the PGA Junior League which provides young golfers in our community access to our course, proper instruction and the life lessons that the game provides, like respect and etiquette. ZCC is the home course for the local high school and we have hosted the Upper Arlington High School Invitational. The Golden Bears are the high school alma mater of THE Golden Bear. Finally, ZCC has hosted an annual pro-am since 1945; the first tournament benefitted a regional hospital for wounded veterans returning home from World War II. Since then, the tournament has raised millions of dollars for the local hospital, providing quality healthcare for the people of East-Central and Southeast Ohio.

How did you come to write the book, Searching for Donald Ross – Golf in the American Heartland at Zanesville Country Club? What did you hope to accomplish?

In 2019, our club engaged Columbus-based architect Dr. Michael Hurdzan to assess a contemplated improvement to the golf course. When I read his report, he described ZCC as “the genius routing of Donald Ross.” Even though I had seen ZCC listed on the Ross Society website, like most members, I had always thought the designer was Charles E. “Chick” Evans, Jr. There is a photograph in our pro shop of Evans teeing off our 10th hole in 1941 during a match with Byron Nelson. The caption on the print identifies Evans as the ZCC architect.

I was familiar with the fact that Hurdzan did work at ZCC in the early 1980s so I figured he knew something we didn’t. Not having his email address, I sent him a question on his website “contact us” portal. To his credit, he responded (he was very gracious during my three-year odyssey of research and writing, answering my many questions and even reading the manuscript. I am indebted to him. Great guy). He responded that he always thought that Zanesville was a Ross design and that the golf course has many Ross characteristics, primarily the bunkering. That set me on my journey of discovery.

At the outset, I did not have a goal to accomplish other than to definitively answer the question of who did the design. As I delved deeper into the research, that goal evolved into a desire to tell the story of golf in my hometown and the people who created a course that I love. So, to challenge myself, I decided to write what I had uncovered. The first attempt was a seven-thousand-word, stream of consciousness screed (self-described as a “massive vowel movement”). With the help of an excellent editor and several reviewers with great suggestions, it evolved into a book that I am proud to say is included in the United States Golf Association’s collection of club histories.

I love the blunt honesty of this line – “In nearly every instance when I uncovered information about an issue, my assumptions were almost always wrong.” Expound on that!

I contemplated including a follow-on line suggesting the reader may want to consider putting the book down at that point. One example was when I began to ponder if Ross was indeed involved with Zanesville. On the golfclubatlas.com site I had read where Evans was involved with a Canadian course called Cutten Fields. The Cutten Fields website indicated that Evans partnered with Stanley Thompson. Cutten Fields is an 18-hole course in Ontario that was built by “Commodities King” Arthur Cutten. Cutten knew Evans from Edgewater in Chicago and gave him the course design at the outset. The Cutten Fields website indicated that Evans needed help with the design and they subsequently brought in Stanley Thompson. So, when I discovered that Ross was involved at ZCC (actually at that time the Zanesville Golf Club or ZGC, they re-incorporated in 1945), I assumed that the club had started with Evans and brought in Ross to assist him. A logical assumption given what I had read about Cutten Fields, but wrong. ZGC started with Ross but switched to Evans after Ross submitted a preliminary plan.

Tell us of the course’s early years as a nine-holer.

There is some question regarding when golf arrived in Zanesville. I have seen references to 1898 and 1899, but I tend to believe written histories from the early twentieth century that identify 1898. But what is not in dispute is where it originated; seven men fashioned 4 crude holes on the infield of the racetrack at the county fairgrounds. After a year or so, they leased farmland near our current high school for a 6-hole course and played there for 3 years before that land was purchased for residential development. They moved across a country lane in 1904 and again had a 6-hole course. The new site was adjacent to the city orphanage and was owned mostly by the estate of the city’s founder. In 1908, they expanded to 9 holes and then built a new 9-hole course encircling the orphanage in 1917. After considering relocating south of the city in 1921, they built a new clubhouse in 1923 for $50,000 ($913,000 in 2024). Some notable early events included hosting J.H. Taylor in 1909 and an exhibition match with Walter Hagen in 1925. When a competing local club announced a move from 9 holes to 18 in the summer of 1930, ZGC began looking for suitable land, (the site where they were located was not suitable for 18 holes), and started the process of planning a new course. In the early 1930s, there wasn’t an 18-hole golf course between Wheeling, W.Va. and Columbus, Ohio. That fact, plus the economic climate of the Great Depression, would cause some to say the effort was an audacious and risky move, especially when they were contemplating abandoning a recent million-dollar investment (current dollars) made in the re-routed course and new clubhouse. As former Ross Society president Brad Becken said to me when he visited ZCC in 2023, “I can’t believe they built a new course on new land at that time.”

Ultimately, the club decided it wanted to expand to 18-holes and the best way to do so was to move to a different location north of town where they could secure 400 acres. Describe the raw site.

ZGC leased 406 acres of the Train-Tannehill farm in 1931 for the current golf course. The farm was owned by Helen Train-Tannehill, the great niece of Moses Dillion Wheeler who assembled nearly 1000 acres of farmland in the area in the mid-to-late nineteenth century. Wheeler came to Zanesville in 1818 from Maryland and made his fortune sending pork products to New Orleans, (I assume via the Muskingum, Ohio and Mississippi Rivers), and bringing back sugar and molasses for sale. The site in 1931 was a working farm with rolling terrain and a stream running north to south through the property. Only 12 acres of trees were removed in the construction of the course, and the terrain today could be described as gently rolling with an elevation of 801 feet at its highest point falling to 724 feet at its lowest on the golf course. The 15th hole has the most elevation change descending 70 feet from tee-to-green. Most of the other holes feature much more modest up or down hill changes. A poster from August of 1931, one month before the golf course construction began, listed farm machinery and livestock for sale further illustrating its nature as a working farm.

Talk then about all the things that happened in the first half of 1931. Ross had submitted a routing plan that the board readily embraced in the spring. Walter Hatch, Ross’s man, was paid $350 for a survey. Yet, the same board then switched to Chick Evans as architect several weeks later in mid-June. Why was Evans even in Ohio?

As refenced previously, the leadership of the Zanesville Golf Club most likely felt a need to build an 18-hole golf course in response to its local competitor announcing in the summer of 1930 its intention to build 9 additional holes. Another possible factor in expanding to 18 holes is that several members travelled to Columbus in 1926 to watch Bobby Jones win the U.S. Open at Scioto Country Club. The Ryder Cup returned to Scioto in 1931, just as Zanesville was making its plans to expand and news reports from that time indicate another delegation made the trip to Columbus. It is evident that they aspired to create a comparable golf course in this community.

The brief timeline went something like: the membership met in November of 1930 and voted to explore expanding. A topographical survey of the Train-Tannehill farm was completed by the local county engineer in the late autumn 1930/early winter 1931. It should be noted that the step of creating a topo was consistent with how Ross would start the design process. A later accounting of the course expenses listed an entry of $421.85 for a “topographical survey”. The club minutes contain a letter dated March 10, 1931; from P.H. Tannehill indicating that his wife would consider leasing her farm to the Zanesville Golf Club. On March 11, 1931, Walter Hatch, an employee of Donald Ross, appeared before the ZGC leadership and presented a “preliminary plan” for a new 18-hole golf course on the Train-Tannehill farm. The club leadership voted unanimously to present the Ross routing to the membership. A notice was sent to the membership on May 12, 1931, calling a meeting to consider the Ross routing and the farm lease. The membership met on May 22, 1931, and approved the plans. The local newspaper included a representation of the Ross routing the next day.

Then, on June 17, 1931, a little over 3 weeks since the membership meeting, Chick Evans appeared in Zanesville and the local paper indicated that he would “superintend” the construction of the new course. Evans was in Ohio to compete in the Western Open in Dayton, two hours west of Zanesville.

So, the logical question is why switch from the preeminent Golden Age Golf Course Architect to someone with few courses to his credit and coming off a project where he had to partner with a more experienced architect? We don’t know the answer for certain but my guess is that since Evans visited Zanesville, and since Ross sent his employee rather than visit himself, combined with the celebrity of Evans as a former U.S. Amateur and U.S. Open Champion (in fact, Evans was the first of only two men to win the U.S. Amateur and U.S. Open in the same year), these considerations may have impressed the club leadership to make the switch.

Why did Evans visit Zanesville? My guess is that the club leadership decided to get the perspective of Jack Munro, a former member at ZGC and the Ohio Amateur Champion in 1918 and 1923. Munro played at least three exhibition rounds with Evans in the early 1920s, including the inaugural round at the Ross-designed Granville Golf Course in October 1924. Munro, by 1931 living in Barberton, Ohio, and selling real estate, may have heard that ZGC was building a new course or received a call asking his opinion and recommended Evans.

Club minutes indicate that Evans returned to Zanesville on July 31, 1931, and presented four sets of plans. The final set was selected and work began the following month. Ultimately, Zanesville paid Evans $1500 for the design. The club voted to pay $350 for “a Hatch survey”. The 1932 expense reconciliation included an entry of $368.95, for “staking, surveys, etc.” The extra $18.95 could have been travel expense reimbursement or some other related expense.

I have thought a great deal about why it switched from Ross to Evans. This, after a lot of research and reflection, is what I believe caused its actions:

Ross prepared his preliminary plan before the lease with Mrs. Tannehill was prepared and well before it was signed. In that lease, Mrs. Tannehill indicated that the Zanesville Golf Club could do anything on her farm except two things: they couldn’t knock down her family farmhouse and they could not disturb the “Indian Mound.” (Native American Mounds are prevalent in this part of Ohio). Ross would not have known of these restrictions when he prepared his preliminary plan. The mound on the Tannehill farm is at the highest elevation, approximately 905 feet. Ross’s 4th hole either went very close or through that Native American Mound. When the leadership realized that they would have to change the routing for at least that hole, it may have contemplated switching to Evans based upon the recommendation of Munro and meeting him on the site in June of 1931.

Another contributing factor may have been that Ross’s 3rd, 4th and 5th holes encircled the Train-Tannehill ancestral farmhouse. She may have seen the routing and indicated that she would be happy to lease her farm to the golf club, but she didn’t want golfers around her farmhouse.

What kind of career did Evans have in regard to golf course architecture and building courses?

According to the book The Golf Course by Cornish and Whitten, Chick Evans studied under Tom Bendelow in the early 1920s. After extensive research, I have identified 9 golf courses where he had some level of involvement ranging from consultant to either architect or co-architect. Most of his work was in the decade of the 1920s culminating with Zanesville starting in the autumn of 1931 and opening on July 4, 1933. In a letter published in the local newspaper before the 1955 Ohio Amateur, Evans wrote that ZCC was “the third of perhaps five complete courses” that he had designed. By “complete”, it probably is safe to assume he was referring to an 18-hole course. It is odd that he wrote “perhaps” indicating some level of uncertainty but understandable given his age (65 in 1955) and the nearly 25 years since the start of ZCC. Given the fact that not many golf courses were being built in the 1930s due to the Great Depression and the fact that he took a job as a wholesale milk salesman in 1931 (an article in 1962 indicated that he had a 31-year career in the business), he most likely did not design any other courses after Zanesville. Regarding the three “complete” courses he was referring to and he is credited with designing: South Shore Country Club, an 18-hole course in Cedar Lake, Indiana, which opened in 1928 (subsequently closed); the aforementioned Cutten Fields with Stanley Thompson which opened in 1931; and then Zanesville in 1933. In 1927, he was hired by the Cook County Commissioners as a consulting architect to build courses in the Forest Preserve but he resigned in 1929, apparently not designing or opening any new courses. Two advertisements in 1932, one in Golf Illustrated and the other in Golfdom, detail his services as “Consulting Golf Engineers”, “Golfographical Surveys” and an extended school for a “Course of Study in Golf Architecture”. For the 9 courses generally credited to Evans in some capacity, I did not include the early-1920s redesign of Chicago Golf Club despite contemporaneous correspondence from C.B. MacDonald asking that the plans be forwarded to Evans and a 1950 newspaper article about an anniversary dinner where the speaker indicates that the present course was “laid-out in 1922-23 with the aid of Mr. MacDonald and Chick Evans.”

Image Courtesy of WGA

In your book, you have some fabulous quotes on Evans and his thoughts/beliefs in golf course architecture. Please share them with us.

In a newspaper column published in 1921, Evans described in detail his golf course design philosophies. “All the lines of the traps, greens and fairways, should fit irregularly into the landscape,” Evans wrote. He continued: “I would like to see the white faces of the bunkers but I would not have many mounds. On the whole, I think I prefer severe hazards like those at Pine Valley….Such holes are instructive. I am a great lover of shorter holes, and I think that my first object would be to make these holes interesting. On my course, I would have less than a 125-yard hole, fiercely guarded, for a perfect cut shot; a 160-yard hole, with less severe trapping, …. a 190-yard hole, with still less trapping for a full iron and a 220-yard hole, with a less guarded green but severe penalties off the line…. the natural lay of the ground with which we are dealing must govern the design of the holes. I want to make clear that on the 220-yard hole I would want the carry from the tee with no chance that a topped shot to run up. Also, I would expect my greens keeper to make the 15 yards or so in front of the greens as perfect as possible thus giving the shots a fair fall”.

Regarding the par 4s and 5s, Evans wrote: “Next, I would turn my attention to holes running from 420 to 460 yards. I would have 7 of these, running in all directions, making variety in any wind. To my notion, these represent the real modern two-shot distance. Then I would make a good long hole of, say, 550 yards and I would bend every energy to make it interesting for strange to say I usually find no enjoyment in the long holes. If they could all be like the seventh at Pine Valley it would be fine, but the usual long hole is a terribly monotonous and characterless affair. Next, I would turn my attention to the distance between 460 and 550 yards. I would compromise and put two holes – one on each side – of about 480 yards, that distance being about the two-shot limit of the present player. Of course, I would make the going easier for the fellow who tried to get home in two. The other four holes I would try to distribute with sharp and careful eye over the two nines striving for two drive and cut shot holes and two drive and mashie holes. These would run between 380 and 400 yards in length. By the time that one had finished playing the 18 holes of this course he would have used every club at least twice, and the putting and trapping would be such that unless every shot was skillfully played it would find trouble. Yet I would not want the tension so great that one would be completely exhausted at the end of the round. I am a firm believer in leaving the back of the green open and severely trapped than is now the case on the usual course. I am decidedly opposed to blind holes except in the few cases where the green is a punch bowl over a high hill and off a tee shot. I prefer to see the bottom of the pin when I have an iron in my hand. It would be understood, too, that I would want the greens undulating and of different sizes. I have given a rough outline of my ideal course, but on such a course with work and play in healthful proportion any golfer should find his heart’s delight.”

Re-reading the article and considering the course as it plays today, his design philosophy is perhaps most apparent on the “one-shot” holes or more commonly referred to as par threes. There is a diversity of lengths of the holes. From the blue tees, holes 8 and 18 play approximately 140 yards, each with severe bunkering, hole 5 plays 180 to 200 yards uphill and hole 12 plays between 190 to 210 yards downhill, depending on tee and hole location. Hole 5 plays southwest to northeast, 12 plays in the opposite direction southeast to northwest, 18 is northwest to southeast and 8 is almost exactly north to south. And, as Chick preferred, playing ZCC today requires the use of every club in your bag.

How was the club in the position to press ahead with a new build in the depths of the Great Depression?

They had money in the bank (equivalent to $267,000 today) and very favorable lease terms from the land owner, but the primary vehicle to finance the project was a new stock subscription of the membership. At the outset, they hoped to raise $35,000 ($718,000 today) through the sale of shares. Additional assistance came through in-kind donation of equipment and machinery from primarily one member (Mr. E.M. Ayers, one of the three members in the book dedication). They had spent $2300 after the first two months of the project, up to nearly $25,000 a year later in October of 1932 and estimated an additional $7500 to finish the course in early 1933. All-in, it appears they spent $35,000 to construct the 18-hole current course that opened on July 4, 1933.

The course that opened, how closely did it follow Ross’s routing?

There are four holes that we play today that are identical in location and very similar design-wise to the Ross routing. Our 7, 8, 9 and 10 are in the exact location as the Ross 14, 15, 16 and 17. Ross had his 14th-hole measure 416 yards but we play it today as a 511-yard par 5 from the blue tees. Additionally, these holes have some of the most prominent Ross design characteristics like bounce bunkers (cross bunkers 30 or 40 yards short of the green) on his 16th and 17th holes – today’s 9 and 10. There are two other holes that are very similar to his design: his 1st hole and today’s 15th hole are very similar downhill drives to a green over a stream, and the Ross 7th hole and the current 5th hole are both 180 yard-plus par 3s from an elevated tee to an elevated green and over a ravine cut by Joe’s Run. The difference between the two designs is the location. Today, the hole is significantly south of where Ross routed it for his return to the clubhouse. Finally, the Ross 11th hole is very similar to today’s 1st hole with his 11th and 7th greens converging near each other like our 1st and 5th holes.

The course opens to rave reviews. Please share the one from the golf writer for the Columbus Citizen.

“Let us, just for the moment, forget the personalities of golf and consider one of the newest, and potentially one of the finest of the central Ohio golf courses. Maybe you’ve played it already; quite a few Columbus folks have. If not, let yourself in for a real treat the first time the opportunity offers. It’s the Zanesville Golf Club, now in its second season, the membership from the old Zanesville and Mangold clubs.

“Naturally, no course is particularly delightful from an artistic standpoint in its second season. Zanesville fairways, partly due to an exceedingly dry early-summer, aren’t all that they will be in another year or two and after its fairway watering system is put into use. The greens, too, need more age to become first rate putting surfaces. You need to realize those things when playing the course. From every other standpoint, it is delightful. Some of the holes, purely from a standpoint of topography, demand to be ranked among the best in the district. One of the most sensational is No. 11 (current Hole 2) where you stand on the tee viewing a creek which intersects the fairway at an angle which demands a full 200-yard carry to go straight for the green. Short or timid drivers can pick out any distance they choose but the tee shot must be placed. The hole is almost the opposite to the first at Granville (current third hole at Granville). Another dandy is the third (Current Hole 12) a par three of 220 yards, over a ravine fronting the tee, then down a slope to the green, which is surrounded on three sides by a wooded ravine. The sixth (current 15 Hole) is a hole for long drivers. It’s down-hill all the way from the tee to a creek, which protects the green 450 yards away. You can get a 300-yard tee shot with ease on this one, which makes it an easy par five. The 13th (current Hole 4) is another nice one. Johnny Florio, was playing it for the first time, … thought it was the best on the course. It’s a left dogleg, 387 yards long, down an aisle of trees all the way. Still another impressive hole is the eighth (current Hole 17) where a drive straight down the middle is penalized by a series of dips. You have to know this one and be able to steer your tee shot to the left of the fairway to avoid trouble.

“Zanesville is a restful course, probably because the horizon almost all the time is a line of trees. The course is filled with natural hazards of all kind, including a 140-yard lake shot at the ninth (current Hole 18), but it isn’t tiresome because there are no real hills, just constant up and downs.

The course was laid out by Chick Evans.” ©Zanesville Times Recorder – USA TODAY NETWORK

How is today’s course vs the one that opened in the 1930s?

As I wrote in the book, today’s course would be very recognizable to the visionaries who built it 90 years ago. It would best be described as an early twentieth century parkland design with greens and tees closely located to facilitate walkers. (The first electric carts appeared at ZCC in 1955, very similar to most other country clubs mid-century). The biggest difference is the proliferation of trees, mostly white pine. I discovered a newspaper article from April 1948 indicating that the local boy scouts planted 2400 pine seedlings in a weekend with the goal of returning the following weekend to plant more. 75 years later, Mother Nature, and her increasingly gusty winds, is beginning to reverse their work. Also, a pond has been added adjacent to the first green to mitigate a wet area. The biggest change, however, was the raising of the 15th green and the second and fourth fairways a few feet to offset the flooding of Joe’s Run as a result of upstream development over the past 75 years.

I thought it was extremely clever how you go hole-by-hole with the 1935 description followed by subsequent changes followed by a quote from the pro in 1960 and one from the pro in 2022. Job well done! Can you share a page from a par 3, a par 4, and a par 5 to show the reader how you did it?

Number 1

1935 Description: A par-five dog-leg that pays off on accuracy. The green is 480 yards away and is trapped deeply on either side. © Zanesville Times Recorder-USA Today Network

Subsequent Changes: Two bunkers that appear in a 1947 aerial photograph right of the fairway approximately 100 to 200 yards from the tee were eliminated, and two bunkers were added at the bend of the dogleg to capture drives missing the fairway right. Trees have been added bordering the fairway to the left. A pond was added in the 1980s left of the green to mitigate a wet area. Mounding and pine trees, screening the practice range and the right side of the first hole, appear to have been added in the 1990s. Black: 534 yards. Blue: 529 yards. White: 460 yards.

1960 Pro Says: Par 5. 520 Yards. A slight dog-leg to the right. Trees and ravine at right prevent long hitters from short-cutting on tee shot. Can be reached on second stroke by the long hitter. An easy starter in golf parlance, it is a “pick up” hole.

2022 Pro Says: A dogleg right, par 5. Two bunkers right of the fairway have players aiming left but trees beckon a miss left. Long hitters can try to carry the right fairway bunkers but require a 280-yard tee shot. If successful, they are rewarded with a reachable par 5 and easy birdie but a pond left of the green provides risk for a miss left and the green is guarded by two greenside bunkers. Most players will play the hole as a three-shot hole choosing their lay-up yardage for their favorite wedge distance. The green gently slopes back to front and over the green is a difficult up and down. A good hole to ease a player into the round.

Number 2

1935 Description: The tee on this hole rises above the fairway which is bordered on the right by trees and crosses a creek on the drive. The green is untrapped, but a strong shot rests among trees to the left. The hole is a par four and is 420 yards long. © Zanesville Times Recorder-USA Today Network

Subsequent Changes: A bunker left of the fairway has been added as well as bunkers at the green left, right and right rear. Additionally, the fairway was elevated to mitigate increased storm water in Joe’s Run which runs the length of the hole on the right. Black: 432 yards. Blue: 412 yards. White 330 yards.

1960 Pro Says: Par 4. 420 yards. A straight-away hole with a creek cutting across fairway and angling along the right side of fairway up to the green. This is one of our best holes.

2022 Pro Says: A strong par 4. A stream (Joe’s Run) runs the length of the hole on the right but there is some room right of the path. A hillside with deep heather severely penalizes a left miss from the tee. Green is well guarded by bunkers and has some significant undulation. Par is a good score on this hole.

Number 5

1935 Description: Bears a narrow fairway that slopes downward on either side. This tee is situated on the edge of the creek. The green is untrapped – if you ever reach it! The hole is 180 yards long and carries a reward for an accurate shot. Par is three. © Zanesville Times Recorder-USA Today Network

Subsequent Changes: Two greenside bunkers, left and right, have been added. Additionally, forward tees have been added across Joe’s Run making for a shorter hole option. Black: 234 yards. Blue: 195 yards. White: 162 yards.

1960 Pro Says: Par 3. 180 yards. One of our best short holes. Tee shot to a green sitting higher than the tee, with a hog back fairway to the right. Trouble to the right and left for a missed tee shot here.

2022 Pro Says: The first of our par three holes. A long, uphill hole with bunkers right and left of the green. The pond from the first hole can come into play on tee balls missing left. The green is sloped back to front

Some writers force a neat, pat ending, but you humbly follow the hole-by-hole description with a chapter entitled Unanswered Questions. The biggest one is of course, who deserves credit for Zanesville? How do you answer that? You have spent hundreds of hours poring over newspaper clippings, club archives, historical aerials, etc.

I’m tempted to respond: “buy the book” but I will answer with what we know, based upon three years research of club archives, minutes, contemporaneous news accounts and some anecdotal information. At the beginning, I felt that if I could locate the blueprints, that would definitively answer that question. I know that the blueprints existed fairly recently, but I was unable to find them after searching every nook and cranny of the clubhouse, including a very dirty trip to the basement.

Here’s what we know: Donald Ross was engaged and paid for a “preliminary plan” that was presented to the leadership of the Zanesville Golf Club by Walter Hatch in March of 1931 and approved by the membership in May of 1931. We know Chick Evans came to Zanesville in June of 1931 and presented four sets of plans the following month. Work started a few weeks later and the course opened for play in 1933. ZGC paid Chick Evans $1500. ZGC paid Ross $350 for the “Hatch Survey.” As Dr. Hurdzan indicated to me, if ZGC paid for the “Hatch Survey” Evans was entitled to use some of the Ross routing. Four of the current holes are nearly identical and a few others strongly resemble the Ross design.

Therefore, one way of answering the question is: Using some of the holes from a preliminary Donald Ross routing, Zanesville Country Club was designed by Chick Evans, the first of only two men to win the U.S. Amateur and the U.S. Open in the same year and the founder of the Evans Scholars which provides higher educational opportunities for caddies nationwide since 1930.

Or, more simply: Zanesville Country Club is a Chick Evans-Donald Ross design.

So where do things stand at Zanesville Country Club today?

As a small town, we are very fortunate to have had ZCC endure for 90 years. Our membership is as high as it’s been for a very long time (202 senior members, 75 junior members, 30 non-resident members, 152 social members for almost 460 members) and our financial position is very stable. To illustrate how fortunate we are, I like to share with our out-of-town guests from more metropolitan communities that we don’t have tee times at ZCC. Just show up and play. We manage it with a bit of common sense and a lot of courtesy (a foursome of walkers will allow a twosome in a cart to tee off first if they arrive at the same time). No tee times is fairly unique and a real luxury we enjoy.

How good could the course be fully restored? And what benchmark will you use for the restoration?

The commitment that I made at the outset of writing the book is that the profits will benefit a project on the golf course. We are not realistically going to be in a position to do a course-wide restoration but we are starting to discuss what projects we could accomplish, depending on cost, amount of funds raised and greatest benefit. For restoration, some projects to consider are tree management, bunker removal and redesign and the stream reclamation in front of 15 green. The aforementioned upstream development created significant run-off requiring the work in the early 1980s to raise the green. The result, the small stream in 1933 is now a 12-foot-wide pond. If any of these is not feasible from a cost standpoint, we have discussed improving the short game practice area or creating a new practice putting green, especially needed since we will have a significant field next year for the Ohio Amateur.

And all the profits from your book go to the restoration?

Yes, all profits from the book sales will benefit a project on the golf course. If the remaining books are sold, we will have $30,000 in the fund. The club has a modernization fund that may be able to augment that amount. Copies can be ordered through the ZCC website: https://www.zanesvillecc.com/Default.aspx?p=dynamicmodule&pageid=82&ssid=100095&vnf=1 It includes a peer-reviewed chapter on Donald Ross, his design characteristics and a biographical chapter on Chick Evans. Dr. Michael Hurdzan read the entire manuscript and graciously contributed the Epilogue, and Tyler Rae, who toured ZCC with me a few summers ago, read the Ross Chapter.

Thank you for your interest in our story.