Best of Golf: Learning from Pinehurst

by

Richard Mandell

June, 2014

In golf architecture, the term Best of Golf will lead to far more subjective thoughts than objectivity. Some prefer the classic golf courses, others more modern layouts. The same can be said of architects and their personal styles. Long par-fours may be preferable over reachable par-fives. Penal vs. strategic. The list goes on and on. But one thing that most of us can agree on is the best soil to build golf courses on is sand. The simple reason is for its ability to drain and the ease of shaping in such a malleable medium.

As the world focuses on the sandhills of North Carolina for these next two weeks, the restoration of Pinehurst No. 2 takes center stage. Being built entirely on sandy soils, No. 2 has inherent advantages over most golf courses, allowing for low-profile features cut deep into existing grade and the ability to promote a ground game today.

Yet for many years prior to the recent changes, that ground game was lost as was the character of the sandhills landscape that made the Pinehurst courses so memorable. In its place was verdant green from tree line to tree line as Pinehurst No. 2 slowly evolved into another U. S. Open venue: A narrow, monochromatic, bore. Bill Coore and Ben Crenshaw’s efforts changed all that.

With Ran’s blessing, I have reproduced the epilogue from my first book, Pinehurst, Home of American Golf ~ The Evolution of a Legend (now out of print and written pre-restoration) as well as an excerpt from my new book, The Legendary Evolution of Pinehurst and the epilogue from the new book as well which calls for change, chronicles the restoration, and puts the work at No. 2 into a broader perspective.

EPILOGUE 2007:

THE FUTURE OF THE SANDHILLS

PINEHURST HAS OFTEN BEEN NICKNAMED THE ST. ANDREWS OF AMERICA. Although there is a strong fraternal relationship between Pinehurst Resort and the St. Andrews Links Trust, that connection stops with the actual golf courses. Layouts in St. Andrews and the North Carolina sandhills are carved out of sandy soils yet the sandy golf features characteristic of Scotland are seldom replicated in the sandhills. Instead of a links strategy and rough conditions, the American ideal of perfectly controlled golf conditioning dominates the sandhills.

Unfortunately, most current golf course design and management trends in the United States are based on controlling the golfer’s playing environment. Each golf hole has perfectly manicured landing areas, fully in view from the tee and waiting to catch everything like an oversized first baseman’s glove. Putting greens have emerald-colored putting surfaces and always stand at attention to the golfer with a welcoming back to front slope. The bounce and roll which helped make golf such a gift in the first place are some of the qualities missing on many of the sandhills area golf courses today. The elements of randomness and mystery have been effectively removed from the game in the process.

For me as a golf course architect, great golf is all about creativity and inventiveness in shot-making, two golfing traits which have become non-essential in golf architecture today. The future sandhills golf course should be dominated by the one site characteristic that truly separates great golf courses from all the rest: SAND. Sandy soil is the defining mechanism of the sandhills area and is the best medium for creativity and inventiveness in golf course design. Yet many golf course designers ignore the freedom sandy conditions provide in golf course design. The future of Pinehurst is a golf course that maximizes the playing characteristics of sandy soils with golf course features that are reflective of conditions found in the links courses of the past.

The compact, spongy underlayment of thatch and native grasses on firm, sandy ground gives links golf its flavor. Undulation, in the form of ridges, ripples, rills, hollows, and knolls, is the primary defense found on a links course. Contours deflect one’s ball from a desired path and at the same time may direct that same ball into bunkers and hollows. Today’s golf should be played along similar links conditions in keeping with the origins of the game and to promote the art of shot-making.

Sandy Pinehurst soils allow the golf course architect to use undulation to create strategic challenges for those golfers seeking out a birdie, yet still allow the lesser-skilled an opportunity to enjoy the game. The incorporation of undulating ground will result in specific targets to gain a considerable advantage. For example, natural ridges can provide landing points for bold tee shots, a stiff downslope shall give the golfer hope of gaining extra yardage, and out of a natural rise a sandy hazard can emerge to entice the golfer with an alternate (yet riskier) route.

Features can be plateau fairway areas that provide better angles or views to the next target or specific quadrants of a putting surface for the aggressive player looking for a short birdie putt. Yet because undulation is truly a hazard which promotes challenge and does not unduly penalize, the disadvantaged can play at a fair pace without fighting their own physical limitations. As baby boomers get older, they will appreciate the ground game.

With the ability to develop the rolling sand dunes of Pinehurst into dramatic links-type features, the golf course architect can correctly develop authentic rolling golf course features that more resemble the waves created by thousands of years of erosion found throughout the British Isles. Many architects fail to accurately replicate natural land forms to use as hollows and mounds. Often times it is a result of poor soil conditions, but more often than not it is the inability to recognize the merits of nature and translate them to the ground. The deficiency in mounds and hollows do not come in the high or low points which most people first recognize. It is in the inability to create broad waves between two high points or two low points. The resulting products are choppy, out of scale chocolate drops.

The future of golf in the sandhills is in creating a golf course that takes full advantage of sand’s ability to sustain low-profile, well-draining golf course features and hazards full of variety and strategy. Sand bunkers can appear simply as extensions out of the ground. They should mimic nature unlike artificial hazards that must be built on top of heavier soils. Sand soils also afford the opportunity to move away from the perfectly manicured fairways and re-introduce the rub of the green – sandy rough areas which bleed out of the pines and creep into the fairway.

By making a conscious effort to develop strategy on a hole by hole basis, the golf course architect can develop enough options to provide a myriad of choices for the golfer. Of course, choices on any soil can only become reality through proper fairway width. Enough of it will blur the black and white choices that render many holes boring after only one or two rounds. Instead, a wide fairway provides enough alternatives that the golfer must ponder a gray area of choices. It is this variety in strategic choice that will create memorable experiences and repeat play.

The practicality of width can provide broad golf course corridors which, in turn, can provide an expansive backyard for the homeowner who may choose to live along this golf course. Moving away from the age-old trend of double-loaded fairways and maximizing home sites, the future of Pinehurst will lay in the creation of premium lots of sufficient acreage. Minimizing the density of homes will create a sense of open space between adjacent homes and across the broad fairways of the golf course. The result will be a more private and natural setting for the homeowner.

A sandhills throwback to golf courses from one hundred years ago will show a new generation of golfers that the simple thrill of hitting a golf ball over, through, and around nature’s wonders is much more entertaining than a perfect lie within a painted picture. A memorable round will result from the architect’s ability to provide strategic options from hole to hole. In turn, these options will allow the golfer to make choices – some correct and some not so correct. Undoubtedly, the golfer will yearn for the prospect of another chance to make the right choice and the golf course developer will reap the benefits of repeat play. The future Pinehurst golf course will not only possess these essential ingredients of great sandy golf, but also be more sensitive to the ground, more environmentally-friendly, and most importantly, affordable to construct and PLAY.

RESTORATION, REBIRTH, AND RENEWAL

“It’s still the same course, just a different presentation.”

-Ben Crenshaw

BACK IN 2007, THE EPILOGUE FOR PINEHURST HOME OF AMERICAN GOLF ~ THE EVOLUTION OF A LEGEND VISUALIZED THE FUTURE PINEHURST GOLF COURSE AS A RETURN TO THE WAY THE GAME USED TO BE PLAYED IN THE DAYS OF DONALD ROSS AND LEONARD TUFTS. This was before the modern ideal of highly manicured and controlled golfing environments took over the game.

The influx of perfect conditions was the first step toward many deteriorating decades of the game of golf. No longer was the game a character builder based on the way the golfer handled adversity. That adversity came with learning to roll with the punches and dealing with the randomness that golf courses of an earlier era threw at the golfer. Instead, no one’s feathers were ruffled with a poor lie and everyone had their route from tee to green clearly delineated with no surprises. In 2008, the deterioration came to a head as the golf business collapsed, halting new development while the world economy fell away.

Some golf course developments were caught mid-construction and never saw the light of day. That may have been a good thing because their business models, albeit standard 2007 fare, had no place in the new golf economy of 2008 and beyond.

One development caught in the crossfire of the collapsing golf economy was The Dormie Club, a private course just north of the Village of Pinehurst designed by Bill Coore and Ben Crenshaw. When asked how Dormie Club would fit into the landscape of Sandhills golf courses, Ben Crenshaw took a modest tack, “We’re just going to try and create something that we hope will be complementary to golf in this area.” His partner made it clear, though, that it wasn’t to be compared to Pinehurst Number Two in any way. “There was no attempt to replicate Number Two other than the native rough.”

OF COURSE, AT THE TIME, THE NATIVE ROUGH AT NUMBER TWO DIDN’T EXIST ANYMORE. As the author walked the course during the 2008 U. S. Amateur, he was struck by how far removed the sand bunkers were from the course of action played on Pinehurst Number Two. The width which Donald Ross relied upon to create angles into his greens was not just out of sight, it was out of everyone’s mind at Pinehurst as well. So how did it happen?

The average tee shot during the 1999 Open at Number Two was 260 yards. It jumped up to 270 yards the following year at Pebble Beach. From that point on, the average tee shot during the U. S. Open was a staggering 291 yards thanks to the introduction of the Titleist Pro V1 golf ball. With the return of the Open to Pinehurst Number Two in 2005, everyone knew the golf course was going to play much shorter for the professionals. “When Tom Meeks got here [in preparation for the 2005 Open] he said, ‘well they are hitting so much farther,’ so the fairways got real narrow, the rough got real high and it was a really hard golf course,” said Don Padgett, II, President of Pinehurst, Inc. since 2004. “I don’t know how many sprinkler heads we added.”

Typical of venues which host the best golfers in the world (pro or amateur), ever since Robert Trent Jones revised numerous classic golf courses in the fifties (Oak Hill and Oakland Hills to name two Ross courses in particular), these classics are narrowed up to penalize a tee shot that may be just a few yards off-line.

The domino effect, at least in golf course design parlance, is that angles are tossed away and there is only one route to take. That means everyone who successfully threads the needle off the tee has the same line into each green (straight ahead). For Number Two, by the time of the 2008 Amateur, hazard placement around greens took on less meaning, just as the fairway hazards lost their effectiveness.

“After 2005, we made the decision to leave the fairway widths the same as they were during the Open and allow an everyday Open experience for our members and guests,” said Padgett. “It also helped from an agronomic standpoint because the difficulty of widening the fairways and then re-growing the rough in such a short period [preparing for the 2008 Amateur] was unnecessary.”

The evolution of Number Two had hit a point of stagnation and dropped in the minds of many. At the end of the last century, Golf Digest considered Number Two the ninth best golf course in the country, but it plummeted to thirty-two just a decade later.

During the semi-final round of the U. S. Amateur, the Author spoke with Mike Davis, USGA Senior Director of Rules and Competitions, regarding the appearance of Number Two and the idea of returning the golf course to its sandy roots was discussed. Davis possessed similar ideas.

Over the next year, those same concerns were raised by a variety of people in the golf business to Mr. Padgett. “Our embryo as I remember it was Mike Davis. I think you [the author] thought it was a good idea,” he said. “Lanny Wadkins raked me over the coals on Father’s Day about how bad the golf course had gotten and how far away it had gotten, so after all those things over a period of time you begin to say, ‘what can we do?’”

At the 2009 U. S. Open at Bethpage, Bob Dedman Jr., Bob Farren (who had spoken with the Author about preliminary restoration ideas earlier that spring) and Padgett (who had heard enough from others) first brought up the need to make changes to Number Two with USGA President Jim Hyler, David Fay, and Mike Davis. The decision to bring back-to-back U. S. Opens had been announced earlier that week, making Pinehurst Number Two the first and only course to host the U.S. Open, U.S. Women’s Open, U.S. Senior Open, U.S. Amateur and U.S. Women’s Amateur.

The restoration project was not initiated specifically because of the Opens. Rather, the project was initiated by Pinehurst, Inc. to protect and restore the resort’s “most significant asset to ensure a successful business model for the future,” according to Farren. Questions of how to minimize manicured turf were brought up to the Author by Farren earlier that spring. He had already eliminated turf between greens and tees but where to accomplish that within the golf holes themselves was the query.

Soon after the Bethpage meeting, Pinehurst, Inc. approached the design team of Bill Coore and Ben Crenshaw to carry out the restoration of Pinehurst Number Two. “Ben Crenshaw’s knowledge and respect for golf history made us very comfortable and Bill Coore grew up in North Carolina and played Number Two on many occasions,” said Padgett. “So they really offered a perfect combination of a proven track record, respect for history and tradition, and knowledge of the course in different eras.”

To Don Padgett, both members of the team were a natural selection for whatever scope of work may occur at Number Two. Yet that scope was far from defined nor was it intended just for the playing of the Opens. It started out to save it from itself, so to speak; to return the course to why it was first famous. The concept is much easier in theory than in practice, though.

First of all, the question of what window of time would the design team ‘peer into’ had to be answered. Although it was always on the same piece of land since its inception, its evolution spanned decades where its reputation was never questioned. One could restore the golf course to many different eras.

On top of that, how would a restoration affect the playing of two major USGA events – events that made their reputation on what the design team was planning to erase. The whole thought of restoration was in response to the stagnation of the course over the past decade in response to the very type of tournaments that were a short five years away from happening once again.

Bill Coore and Ben Crenshaw understood the ramifications of what was about to happen and they carefully weighed the implications of what could come out of a true restoration project before they signed on to the work. They had trepidation about the enormity of the task because each of them had a long personal history with Number Two.

Born in 1946, Bill Coore grew up just over an hour west of Pinehurst in Davidson County, North Carolina. The golf courses he played as a child more resembled Pinehurst Number Two in its infancy. They were less than nondescript with little strategic or visual interest. One day as a teenager, Coore stepped on to the first tee of Number Two for the first time as a caddy for his next-door neighbor, Donald Jarrett. He had heard of Pinehurst before and was excited to be on such hallowed ground. “I probably liked it because of all the great players who played there and all the events throughout history at Pinehurst that occurred there. Did I totally appreciate the golf course? Probably not,” Coore confided.

Subsequent loops followed. As he began playing golf himself elsewhere and watching other golf courses on television, the differences he saw in the Number Two course of the sixties made an impression. “I would watch golf on television like most people who enjoy it. Most of the courses were more well-manicured and ornamental type,” said Coore. “When you went to Number Two, it was much more natural in its appearance and presentation. It had rough edges and it had native rough with sand and wire grass and pine straw.”

Coore went on to play college golf at Wake Forest where the team’s home course was a Perry Maxwell layout called Old Town Club in Winston-Salem. Maxwell, a golf architect from Oklahoma, was friends of the Reynolds tobacco family and had designed a few projects in the Tar Heel State in the early forties.

Yet it was Number Two that shaped his early thoughts on golf and golf design. “More than anything, I guess we all gravitate towards courses that allow us to play our games. I would see some of the very best players [professional and amateur] in America play at Pinehurst,” Coore said. “Number Two allowed them to play whatever type of game which they were most comfortable. I began to appreciate that. That was basically the cornerstone.”

It would be decades before he would bring that cornerstone to practice as a designer. After earning a degree, he spent two years at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, about an hour from Pinehurst. Upon discharge, he visited a new course under construction in Winston–Salem called Oak Hollow where he met Pete Dye. Bill began working construction for Pete at the Cardinal Club in Greensboro shortly thereafter. He then went on to work for Pete’s brother, Roy Dye, north of Houston at a project called Waterwood National. By the time grow-in began, he was entrenched as the golf course superintendent.

Around that time, not too far from Waterwood, Ben Crenshaw was battling Tom Kite, Bill Rodgers, and Bruce Lietzke in high school before moving on to the University of Texas. He first laid eyes on Number Two in the early seventies, spurred on by many of his compatriots to see the course. Crenshaw remembers:

“Pinehurst was so well talked about by so many people that I had to go see it. I walked around and I could see why Gary Koch and Vinny Giles and Bill Campbell were such proponents of it. It was everything that I ever thought of. I thought the bunkering was very unique. Where the bunkers are, how they shape the holes and shape the approaches. I was fascinated by that. Donald Ross was obviously one of the best at that. They did have slippery greens and yes some of them were convex. I had not seen many courses where that was the case.”

Over the years, Number Two reached masterpiece status with Crenshaw, from his first playing of it in the 1973 World Open to his last, the 1999 U. S. Open. To him, that status comes mostly from the routing and how the property is just right for a golf course. In other words, the highs are just high enough and the lows are just low enough. Crenshaw describes the roll of the ground as not violent movements, but “very dramatic sweeps and movements that are beautifully and gracefully done.”

An example is how the thirteenth hole rises just enough and then the tee shot for fourteen cascades back down. He considers the fourteenth hole as one of the most beautiful he has ever seen. When discussing Ross’ routing: “It’s just how he spread the holes out in such different fashions and the combinations of play,” said Crenshaw. “Movements are there when you dip into the valley on four and five and on eight and on the back nine (sixteen, seventeen, and eighteen).”

Ben Crenshaw met Bill Coore just months after he won his first Masters in 1984. Later that year, Crenshaw suggested a more permanent relationship, one that was at its peak when they were hired for the Number Two restoration almost a quarter-century later.

DORMIE CLUB WAS UNDERWAY AT THE TIME AND THE WORK THEY ALREADY COMPLETED WAS A PERFECT SAMPLING OF WHAT NUMBER TWO COULD RETURN TO IN A RESTORATION EFFORT. “It was just a natural progression to say Bill and Ben were already here [working at Dormie],” recalled Padgett. But it would be four or five months after they were first approached before they agreed to take on the job. Coore recalled:

“The course I was looking at could have been anywhere in America. It had lost its individual character and identity. When I walked down and looked over hole four, looked backwards down number five, and turned and looked at the sixth hole, it had basically become a sea of Bermuda grass from tree-line to tree-line. The Pinehurst that I had first experienced, that rough, scruffy, natural, yet fascinating course where the fairways and playing areas were so extraordinarily well-defined against the native rough was gone. Ben had seen it as well.”

“It’s a very problematic thing to think about all the things that in our opinion were a little out of kilter. The lines of play and the corridors just didn’t seem right with all the Bermuda together,” said Crenshaw. “My thoughts were that we could improve it.”

So the grilling began. Before Coore and Crenshaw agreed to take on the challenge, they had to be sure their vision was shared. Frankly, they were skeptical that both the Pinehurst group and the USGA truly understood what they were asking for in the name of restoring Pinehurst Number Two.

“One [question] was ‘If you are asking us to restore it, restore it to what?’ because this golf course has evolved so dramatically through the decades that you could pick different eras and say this is what we’re going to go to,” said Coore. “Which one do you see it being?” Padgett’s response put it back on Coore and Crenshaw, “Well guys that’s up to you. It’s your decision,” he said. “We will weigh in on it, but it’s your decision as to what it should be restored to.” To Coore, the answer from Padgett wasn’t necessarily unnerving, but daunting in the least. It was clear the Pinehurst people had no specific direction at the time.

The period between Ross’ initial grassing of the greens until the time he passed away thirteen years later was when the course was at its architectural peak. “The course that we would try to recapture, that course came into being in 1935 and existed probably up until about the time that I first saw it in the early 1960s,” said Coore.

But the specific focus of their restoration efforts would be the end of Donald Ross’ life. This is a key focal point because the bunker work most people associated with Number Two was actual grass–faced bunkering with flat sand as a result of Henson Maples’ cost–cutting efforts in the early fifties. The photographs and aerials Coore and Crenshaw were most inspired by were of the flashed sand bunkering of Donald Ross, an aspect of design Ross himself would recognize much more than what Maples gave the world.

“We just felt, at the time of his death, even though it had gone through a world war, that would be the course of which he would’ve been most proud,” said Coore. “That’s how we came to the conclusion this is what we’ll try to go back to, the course that we believe he wanted there.” Dedman and Padgett were more than on board with that decision. In fact, they practically turned the keys over to them, “Bill said ‘We are going to roll the dice and do it 110% of what we think you need to do,’” recalled Padgett.

Once that decision was made, the next set of questions was for Mike Davis and the USGA because mid-century Pinehurst Number Two was the polar opposite of almost every U. S. Open venue for decades, particularly the Pinehurst Number Two of 1999 and 2005. Both the design team and Pinehurst, Inc. were unsure of how to adapt their vision to the USGA’s goal of identifying the “best player in the world”. For the U. S. Open, the USGA usually accomplished that through a process of survival of the fittest determined by narrow fairways and deep rough.

The first question regarded fairway widths. Coore and Crenshaw had every intention of re-capturing the optional angles of play that Ross so deftly developed over the years. “Pinehurst Number Two requires judgment and it sure rewards strategic play, even if there is a marked difference in playing from one side of the fairway to the other, depending on where the flagstick is located,” noted Crenshaw. “That sort of thought repeats itself all over the golf course. You want to play position golf. It rewards that thoughtful play.”

Unfortunately that sentiment flies in the face of professional golf, at least on the Pinehurst side of the Atlantic. Bill Coore was very up front with Mike Davis on the subject when he told him that the fairways would be much wider than they were currently mowed, “Mike, you’re going to have sandy rough for your championship and it’s going to be very awkward.” Bill’s biggest worry was that the USGA would insist on deep rough between the fairways and the sandy natural areas the design team envisioned along each hole. Davis surprised Coore with his intention to stray from the standard USGA setup, a practice he has slowly adopted ever since he took over setup of Open venues in 2005.

“We were standing right along the left fairway bunkers on hole number one, and I remember looking at him. ‘Mike, you’re saying that you’re not going to grow Bermuda rough to play your national championship on if we restore this golf course and put the sandy wire grass rough back?’ He said ‘No, we won’t do that. You guys set the width,’” recalled Coore. Mike Davis insisted to Bill Coore that he and Ben must make the golf course the best that it can be for Pinehurst, first and foremost.

On the Pinehurst, Inc. side, Dedman and Padgett were still struggling with the conflicting ideals of restoration without rough on an Open venue. Padgett remembers they both were automatically resigned to the fact that the USGA was too influenced by par as a measuring stick, “Neither one of us gave it any real thought because we were still tied to 280. As long as they wanted 280 to win the Open, I didn’t know how you did that without the rough,” he said. Once Davis assured that wasn’t going to be the case, the game was on in Padgett’s mind. Davis told him, “I don’t care if a high single digit or 10-11-12 under par won the Open. If the golf course played the way it should, we’d be happy.” That opened everyone’s mind to a whole different array of possibilities. “Once that was off the table, everybody got together and said ‘you know what, maybe we can get this done,” said Padgett.

Not much for detailed drawings, the team of Coore and Crenshaw leans more toward a design/build philosophy. More so than that, they actually lean toward an experiment/build philosophy. The only design work that took place prior to groundbreaking was the decision to restore the course back to the post-grassing era of 1935. It was the details that would bring up a lot of questions for the team. “We felt like we knew, in general, what the course should be like. But we knew there were going to be a lot of judgment calls,” said Coore. “Where exactly were the fairways? Where was the sandy wire grass rough? How far exactly did some bunkers extend? How far up the faces was the sand?” They always approach a new project with eyes wide open. Only when their team of shapers gets on site and begins the process of actually moving dirt does the design process take place. Ideas are shared among the group, individual shapers may be working toward one concept in one spot of the property and another elsewhere, or the principals may have ideas that are contingent upon what the shapers can or can’t do with the ground.

Their team has been together long enough that it is a very effective process of experimentation. In fact, design associate Dave Axland has been with Bill Coore since he left Waterwood National and designed his first golf course in Rockport, Texas. Other team members were Dan Proctor, Jimbo Wright, and free-lancers Kyle Franz, George Waters, and Brian Caesar. Toby Cobb was the project manager and was most familiar with Pinehurst, which he visited often while managing the Dormie Club project.

Coore and Crenshaw spent many days on site digesting the work of their team and finalizing the next steps in the evolution. Coore’s direction came in the details of shaping and Crenshaw’s job was to look at everything from a more holistic viewpoint, considering Coore’s focus is usually very directed on a micro-level. “My task was to bring it into a perspective of what we thought it could be and what was there,” said Crenshaw. “That involves so many things that we talked about like lines, bringing out bunkers, making them slightly more prominent, the swings of the fairways, all of those put together.”

THE SANDY ROUGH LOOK WAS THE BIG CHALLENGE TO DEFINE. “We reduced it to a simple proposition: what the ground looked like when Ross tackled the golf course. What did it look like without anybody having anything to do with it? It was that sandy ground, certainly non-cultivated, wispy, pine cones, pine straw,” Crenshaw said. He visited Number Two seven times throughout the process and stayed multiple days.

Construction began in March of 2010 on holes eleven, twelve, and thirteen which were somewhat isolated from the daily activity of the resort. “We started in the back away from the road and all the watchful eyes to get our feet on the ground a little bit,” recounts Bob Farren, Director of Grounds and Golf Course Management since 2008. But with Number Two still open for play until November, it was hard to keep things under wraps. Coore recounted:

“I remember Toby Cobb saying that one day a man walked up to him and said ‘What the hell are you guys doing? Who’s ever heard of getting rid of grass? Most golf courses try to grow it. What are you doing?’ I’m sure that was troubling for a lot of people because it wasn’t like the grass went away and suddenly the wire grass and pine straw reappeared. You had to get rid of the Bermuda first and that’s an entire summer of effort to do that.”

The obvious areas of Bermuda removal were tackled first. “From an agronomic standpoint, trying to remove Bermuda turf in March is difficult. If you take a sod cutter and remove it, it’s going to grow back in June and July,” said Farren. “By the time we got to May, some of the grass that we had taken off was starting to regenerate itself, so we started spraying some of that and excavated some sand here and there without disturbing the ground because we wanted the native vegetation to recover.”

Although the first phase of the project was underway, everyone was still a bit edgy as to the details. Experimentation by a trusted group of experienced shapers and designers sufficed, but without concrete evidence to show the way, there would always be doubt. Other than old photographs of the course taken at eye level, there was no other documentation of what the course actually looked like. The only known drawings of Number Two were a routing from 1911 and the undated notes from Ross regarding updates to the first three holes. There was a 1939 aerial photograph the Author discovered in the Tufts Archives as well as Ross’ routing of the course from the 1936 PGA Championship program to consider but they were not as detailed and clear as the design team preferred.

Two fortuitous events did come to pass in the early days of the renovation which gave everyone the solid direction they were seeking. First, a little local knowledge came from Farren, who first arrived at Pinehurst in 1982. Like old family lore passed down from generation to generation, he was well aware that the original Buckner irrigation mainline installed back in 1933 never moved. Since that was the case, flagging those mainlines should produce the fairway centerlines from the thirties.

From there, a simple understanding of how far the irrigation heads threw water back then would reveal the original edges of the fairways. Beyond those edges was sandy waste. Those original Buckner Rotary Cam Drive Sprinklers were patented in 1931 and were designed to throw water anywhere from ninety to one hundred and twenty-feet. This was vital information in the attempt to reverse the Bermuda crawl that began with Richard Tuft’s 1962 renovations. A handy by-product of the flagging exercise is that it also revealed how straightened out each golf hole had become over the years. “Instead of it being straight like the fairways currently were mowed, it was a very serpentine thing following the contours of the ground,” said Coore. “Ben and I felt here’s a strong key to help us decide where the fairways exactly were and likely not Bermuda grass off the sides of them.”

The channelization of the original meandering fairways came about not just from the addition of Bermuda rough and irrigation heads over the years, but also through the addition of tee boxes in response to all the professional events played on Number Two.

One example is the lengthening of the fourth hole for the 2005 Open. The only way to gain length was to abandon the original tee beside the fifth green and stick a new tee way back to the right of the sixth tee on the opposite side of the restrooms. This move did add yardage, but it effectively straightened the golf hole. The fairway bunker to the left of the first landing area was reduced to catching a stray hook off the new tee rather than challenging the golfer to to cut the corner over the bunker from the old tee and take advantage of the roll of the ground to bound even farther toward the green.

The second event involved a man named Craig Disher, who approached Bill Coore with low-altitude 1943 aerial photographs of Pinehurst Number Two of very high quality detail. Disher worked intelligence for the U. S. government for almost thirty years. Upon retirement, he followed an affinity for golf architecture straight to the National Archives where he found a vast collection of aerials taken in the 1930s and 1940s by the Department of Agriculture and the War Department.

After learning of the work planned by Coore and Crenshaw, Craig returned to the National Archives to search the War Department collection. The photos of Number Two he found were a by-product of the U. S. Army’s aerial mapping of nearby Fort Bragg, despite being about thirty miles away. The aerial cameras in those planes permanently filmed the ground from takeoff to landing. Because of their immense size and subsequent inability to turn sharply, Disher had a hunch that they recorded the ground from as far away as Pinehurst while making turns. His hunch was correct and he invited Coore over to his house to view the aerials.

“On his table he had laid out aerial photographs of every single hole on Pinehurst Number Two, amazing photography taken on Christmas Day 1943. He knew the exact time of day to the minute,” recalled Coore. When he took those pictures out on site, it was clear that Farren’s approximation of the irrigation mainline perfectly aligned with Disher’s Christmas Day aerials. “The fairway went from here to here, it meandered this way, it turned that way, and it followed the landscape and the contours beautifully,” said Coore.

For Coore and the rest of the team, it eliminated any more supposition and judgment and brought them into the realm of absolution. “We basically had it right in front of us and that became our blueprint,” he said. “We could proceed with confidence as to how wide these fairways were, where there were bunkers that no longer existed, those that had been covered over, and where there were new bunkers that had been added.”

So the removal of the Bermuda grass continued. The design team simply pulled the tape lines seventy feet off of the centerline pipes in each direction as a starting point for the fairway edges. It also revealed those historic fairway swings Ben Crenshaw spoke of as a critical feature of Ross’ work.

The intention was to minimize manicured turf from a maintenance standpoint and eliminate all rough-height grasses from a playability standpoint. In other words, there will be only two grass heights on the golf course: putting surface and fairway. When the golfer misses the fairway, the result will be a variety of sandy surfaces as well as pine cones and other natural impediments, wire grass and other native plants, and pine straw.

In essence, the project was broken into two periods. The first was the work completed while Number Two was still open for play, which lasted until November. The next period began when the course was officially closed and work around the greens and other golf course features could begin unimpeded. “We knew the course wouldn’t close until November so we saved some of the heavy lifting aspects around the green side features until the course was closed,” said Farren.

The primary wave of Bermuda removal added up to more than forty acres of very high-quality sod. At that point, the first step of sustainability in the project was taken when Pinehurst, Inc. sent the grass to ball fields, schools, and other community properties. It also found its way into many people’s backyards. Practicality aside, the personal experience was similar to fans buying vials of the infield sand when Yankee Stadium was torn down.

Once the majority of areas were stripped of sod for the reduction side of the project, the detail work of the exact fairway/native area lines for restoration’s sake took on more urgency. The specific removal of most of the sod was done fairly consistently with a sod-cutter. What remained of the areas of stripped Bermuda were sandy surfaces which varied in firmness, from hardpan to pockets of sugar sand where balls may sit down a bit. In Mike Davis’ mind, this was the perfect combination of playing surfaces that could replace the nightmarish deep Open rough everyone came to expect.

Other areas, where the grass seemed to have been established for a longer period, weren’t so easily stripped. In those spots, the construction crews left the grass in place. Knowing that irrigation would be removed from the area, the team let nature take its course by letting the grass starve itself into a distressed state along with the help of some Round-Up.

At that point, they scraped the surface as much as possible, stripping the blades away, and mixed native sand over the top of the base. Then the crew blended the materials together. Through experimentation of how much sand to add and how to blend it properly, it eventually took on the sandy look they were shooting for but also made for a very bouncy, firm playing surface.

The sandy variation of the roughs is the exact hazard the professionals detest the most: unpredictability. Typically, they know what to expect from four or five inch rough. Eradication from those lies is pretty consistent from hole to hole and course to course so they have devised ways to combat the challenge when it presents itself. But sandy lies that vary from spot to spot will do nothing but frustrate the pro golfer. The randomness of wiregrass plants and other natives within the rough will create even more unpredictability for the best golfers in the world.

“There’s no question that these guys will drive it off line,” says Crenshaw. “You could have a lie where you can try to do things to get the ball to the green or just up around the green. Sometimes you may get a lie beside wiregrass which stops you and you have to play adjacent out to the fairway. There’s a lot of luck involved and that’s a part of the game.”

While most of the focus is on how the golfer will handle the sandy lies, the pine straw can create just as much challenge as anything the golfer will encounter at Pinehurst. Shots on pine straw can be more challenging than in rough because of the possibility of slipping as well as the ball moving at address. There is more randomness in that as opposed to deep rough, where you know it isn’t going anywhere.

Not only were all vestiges of Bermuda rough eliminated from Number Two, but the fairways doubled in size from the 23-27 yard widths the professionals encountered during the first two Opens. For the 2014 Opens, the fairway will be anywhere from 10%-50% wider. The detail of that exact transition line between fairway and rough was critical to Mike Davis’ Open course setup. Typically, the USGA will come into a club a year in advance and begin to establish fairway lines and the grounds crew would simply mow to those lines.

Yet because the traditional rough of Number Two was replaced with the native areas, that specific task for course setup had to be done on a more permanent basis during the renovation process itself. As the details came forth of the grass removal, Farren, Coore, and Davis continually consulted on how much grass to remove in key areas, particularly in the landing areas for the pro golfers which range anywhere from 280 to 330 yards off the championship tee.

“Mike might say I’d like to take out another ten feet over here and Bill would say let’s do six and see what it looks like. Then we would come back and do another foot,” said Farren.

“We’d take some off; we’d sort of study it. We’d talk about it ourselves with Mike Davis,” said Coore. “Mike was very comfortable, even though the fairways were going to be hugely wide by Open standards.”

Along with the elimination of rough came the elimination of seven hundred irrigation heads, leaving the course with four hundred and fifty heads, half of which are found around tees and greens. What remained was an old-fashioned single-row irrigation system unheard of in this day and age. The total irrigated area was reduced from approximately eighty-five acres to forty-five acres.

Once the Bermuda grass was removed, the process of planting more than 200,000 native wiregrass plants began. The majority of plants arrived daily from a variety of Moore County locations. A separate crew spent many days planting anywhere from 600-1,000 wiregrass plants from sunup to sundown.

Transforming unnatural areas such as acres of Bermuda rough into natural-appearing features requires a deft eye. Randomness is much harder to pull off when you are intentionally trying to replicate it because human nature tends toward order. To replicate nature requires as much artistic ability as any other form of art. Fortunately for Pinehurst, Inc. a crew of manual laborers became specialists in the art of random by the time the last wiregrass plant went in the ground.

The other transitional element the team grappled with between the fairway and the native areas was the sand bunker placement. These are the features which give a golf course its most visual character, especially when surrounded by contrasting green grass. At Number Two it would be different because the bunkering would be well-defined on the fairway side yet recede into the native roughs on the back end. In fact, in many places the bunkers would simply float into the native areas, leaving its definition behind.

Although the rough areas were now characterized by a variety of sandy conditions, the sand bunkers were constructed in a different manner. For starters, the bunker sand itself was a combination of varying colors and textures to add yet another element of randomness to the layout.

The laborers in charge of planting the wiregrass weren’t the only ones on site who had to re-create randomness in nature. Coore and Crenshaw’s shapers were already in tune as much of their original work is of the minimal, natural style. Yet Bill was quick to point out that his men weren’t creating Coore and Crenshaw bunkers. “We were not trying to build bunkers that look like our bunkers. They happen to have a strong resemblance, but we were trying to restore what we were seeing,” he said.

The difference between Coore’s original bunkering and what was done at Number Two can be seen most clearly at the greens. “We have built greens where the bunkers are cut right into the side, right below the surfaces of the greens. But more times than not, we build bunkers that are set in behind the greens a little bit. It didn’t just cascade over the crown right into the bunker like those at Number Two,” said Coore.

Beyond the way the bunkers were to recede into the native areas, the other major change was the flashing that would return to the bunker faces. Eliminated by Henson Maples in a cost-cutting measure after Ross’ death, the grass-faced, flat sand bunkers of the past half-century became gospel to the Ross restoration experts that have roamed the earth since the nineties.

The fact is they all got it wrong. Evidence in plain sight pointed to sand flashed bunkering as a tool incorporated by Ross in Pinehurst and elsewhere as well as concave bottoms on Ross’ smaller bunkers. Coore and Crenshaw could have started with Ross’ standard bunker details that clearly show concave bottoms and flashing, or any of his numerous quotes belaboring the fact he felt strongly toward, such as “To keep them in condition, sand must be used plentifully. The whole scooped out surface should be completely covered with it (sand).”

Instead, the design team simply referred to the numerous photos of Number Two found in the Tufts Archives which repeatedly show dramatic flashed-sand bunkering instead of the blandly-appearing grass faces everyone associated with Ross bunkers in the past.

The only machine utilized in the bunkers was a mini-excavator which looks like a dwarf backhoe. The job of the mini-excavator is to dig out the old bunkers by removing the existing sand and digging out a new bunker floor. In addition to being project manager, Toby Cobb performed the mini-excavator work as well. He was in charge of replacing those perfect bunker lines with an appearance Bill Coore would loosely term “haphazard.” Instead of a clean edge, the goal was a rough-hewn appearance replicating erosion in nature.

Once the bunker is shelled out, the bucket is then used to break up the old defined bunker edges. This is where an artistic eye is critical as the name of the game is elimination of every straight line, every repeating shape, and every consistently smooth feature surrounding each bunker.

The remaining tasks of cutting out the bunker edges and planting the surrounds are done by a shovel or hoe, but also in a creative attempt to interrupt order. “The goal of the bunkering was to tie the bunkers as seamlessly as possible into the surrounds,” said Kyle Franz, one of the contract shapers working his first project with Coore and Crenshaw. “Overall it required more intensive hand labor than any other project I’ve worked on. This created a fun and interesting process, as often times the primary tool creating shape wasn’t a machine but simply how a bunker was planted with wiregrass and edged to create texture,” he said. By texture, Franz was referring to the eradication of a smooth and tidy surface.

The 1943 aerial photography proved invaluable to the bunker re-construction efforts. For starters, the design team eliminated four bunkers that were not original to the 1943 aerial on holes ten, thirteen, seventeen, and eighteen. Five bunkers from 1943 were restored during the project. These included the fairway bunker off the tee on hole five, to the left of the landing area on hole seven, one fairway bunker very close to its original location on hole eight, a fairway bunker to the left side of the fairway on number twelve, and one on the right side of the first landing area on sixteen.

In addition, three new bunkers were added in both landing areas of the fourth hole, three new sand bunkers were added to the corner of the dogleg of the seventh hole, another bunker was added along the left side of the tenth hole between the landing areas, and one was added past the two restored bunkers along the right side of thirteen. Many pairs of bunkers separated for ease of maintenance access over the years, were consolidated into single bunkers once again. The team decided not to restore nine bunkers from 1943.

Some of the remaining sand bunkers were completely re-constructed, yet others were barely touched. Yet no matter how little work was done to the sand bunkers, laborers brought the sand up the faces of each one. Some bunker edges on the fairway sides were lowered from years of sand accumulation that effectively repelled golf balls back toward play. Even the bunkers which weren’t changed had a shovel or hoe run along the edges to scruff up the old lines and create a more blurred edge.

By November, with play on Number Two finally halted, the resort ramped up renovation efforts. Pinehurst, Inc. had no plans to touch the greens as part of the project but by mid-summer, the third and fifth greens were infiltrated by poa annua. Poa is a perfectly acceptable green surface in the north but in Pinehurst, it is a veritable death sentence for greens. As temperatures continually rose above triple digits, number eleven started slipping. By late summer, even more greens showed signs of stress. The poa infiltration actually began a few years before and mushroomed as a result of the overseeding in the fairways and greens surrounds with Rye.

“We were dealing with miserable summer weather, the worst for bent greens that you ever imagined,” recalled Farren. The decision was made to strip the greens of the G2 bent and re-sod them with A-1/A-4 bent, which was more heat-tolerant. “It was obvious there was so much poa in them. Once we reached a certain threshold, we asked, what’s enough?” Farren said. “It became apparent by early fall that we needed to do them all to be consistent throughout the course.”

But with challenge came opportunity as the re-grassing allowed for a few minor changes to the fifteenth and seventeenth greens. A back right hole location was re-created on fifteen based on an old photograph found at the Tufts Archives. This was done by expanding the putting surface about two paces in that direction. The front of seventeen green was expanded toward the tee, providing for a pin position just over the front right sand bunker.

Once the old G2 sod was removed, the step of removing two additional inches of thatch was thought to return the putting surfaces closer to the elevation they were prior to the 1996 re-grassing. Combined with flashing the sand faces of the greenside bunkers, the putting surfaces appeared much less elevated to the naked eye. The slightly lower profile re-captured what the greens appeared like before Diamondhead shaved the perimeters away in the early seventies. Renovations continued for the rest of 2010, with final touches applied into 2011. Continued visits by Coore and Davis ensured that the details were worked out until the end. On March 3rd, Pinehurst Number Two re-opened, resembling the days of Donald Ross and Frank Maples. The day before, Mike Davis was named Executive Director of the USGA.

For Bob Farren and his full-time staff of thirteen and numerous part-timers, the challenges were just beginning. In June of 2010, Kevin Robinson was promoted to Superintendent of Number Two from the same role at Nos. 6 and 7, right in the middle of the work. What they have on their hands now is a great example of sustainability in motion and a true throwback to a simpler time in golf course architecture. But would everyday maintenance on Number Two be simpler as well?

“PEOPLE ASK HOW MUCH MONEY I SAVE BY NOT HAVING ALL THAT GRASS TO MOW?” REFLECTED FARREN. The simple task of mowing rough areas was predictable enough that he knows how long it will take for two people to mow rough on rotary mowers. “But now, it might take six people or it may take two people a couple of weeks to work in them [native areas] and then you get rain in June or July and two weeks after that rain, everything just explodes. Then you need eight people. It’s a moving target all the time.”

In addition to man-hours being re-distributed from rough mowing to native area maintenance, the resort decided to discontinue overseeding in the fall, also freeing up hours. This is a great step toward healthier turf as well as fast and firm conditions year-round. As a result of minimizing turf areas and eliminating the overseeding, Pinehurst, Inc. reduced their water footprint from fifty million gallons of water per year to between twelve and fifteen million gallons of water, according to Farren.

From one perspective, developing native areas is a sustainable practice as demonstrated by the reduction in water usage. From another perspective one is simply cultivating weeds. For a golf course maintenance crew that once prided itself on how quickly it took from the time a pine cone fell on the ground before someone came along to pick it up, management of such an environment can be daunting.

Questions abound on a day-to-day basis and the answers not only required some horticultural knowledge, but an artistic eye as well. The first step toward efficient management came with the assistance of a group of North Carolina State University professors led by Dr. Danesha Seth Carly of the Office of Sustainability Programs. Since the turf was removed and water eliminated from the native areas, the NCSU team identified forty-six volunteer plants. The scientists developed a plant identification book with the assistance of the Number Two staff, which is broken into five sections and conveniently sized to fit in each crew member’s pocket. Every plant found on site has its own page with pictures, identifying characteristics, and bloom periods. Native plants among the volunteers include Broomsedge, Pineweed, Eastern pricklypear, and winged sumac. Foreign species include Bahia grass, Large crabgrass, and Mexican Clover.

Regardless of origin, the question of when to eradicate and when to preserve is foremost in the staff’s mind on a daily basis. “I wouldn’t say we have encouraged these plants, but we have allowed them to grow,” said Farren. “Some we manage, some we pull out, some we spray, some we will tolerate, and some we don’t.”

Each plant reaches a certain size and density threshold that requires action, yet that threshold changes depending on the weather. The hotter and wetter the weather is, the more action (removal) is required. The obvious approach most people would take in their own backyards is the same management practice followed on Number Two. A weed that is as big as a desk will probably be removed, yet something as small as a Post-it note will probably be left alone.

One aspect of the restoration that wasn’t anticipated is the changing landscape of the native areas from season to season. “One of the interesting things is you could play the course once a month for a year and it would be different every time,” says Farren. After spring annuals (such as Cutleaf Evening Primrose and Hare’s Foot Clover) bloom and mature they are removed, opening up space for the next generation of summer annuals that come along (such as Fleabane and Butterfly-pea). As they harden off in the fall, others take their place.

ALTHOUGH HE WAS PROMOTED TO EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, MIKE DAVIS STILL HELD ON TO HIS RESPONSIBILITY AS THE USGA PRIMARY SETUP MAN FOR THE MEN’S U. S. OPEN. In 2014 he will once again direct setup for the Women’s Open as well. The plan is for the Men’s Open to be played the week before the Women’s Open and the reasons are purely based on putting surface performance. “In a perfect world, if we can have the weather we want the first week, the only change we would want for the second week would be for the greens to be somewhat more receptive,” said Farren. “That will be a matter of probably just a drink of water on Sunday evening [after the men play] if there is no moisture in them.” Davis wants the greens to be slightly softer for the women because they can’t put as much spin on the ball as the men.

The greens will roll between an 11.5-12.0 on the stimpmeter for both groups, though, which is at the threshold of what the Ross greens can allow. Beyond variations in green firmness and different tee boxes, the course setup will be exactly the same. Day-to-day, pin placements for the women will mirror those for the men. For example, on two consecutive Sundays, both events will conclude playing to the same cups for all eighteen holes.

With a difference in tee locations, the plan is for the men and the women to generally have the same club into each green. This strategy will not only make for an interesting comparison between genders, but also avoid divots from one week affecting fairway lies the next week.

Throughout the restoration project, there were few instances where decisions were made that favored those two weeks in June over the long-term considerations for Pinehurst Number Two as a whole, something that rarely happens at other U. S. Open venues. “There are a few spots out there that probably the fairways were more narrow than Ben and I would’ve had them for the vast majority of play,” said Coore.

He cites only a few examples: “Perhaps hole number one – to a degree if one gets past the fairway bunkers on the left, that’s a little more narrow than how we would’ve had it,” Coore said. He also considers the third fairway and between landing areas on ten as possible stretches, but cautions that those choices are not too out of line. Other changes to the course specifically for the Opens are mounds added to the left of eight and sixteen fairways as well as some work on the seventh fairway.

Some restored bunkers will definitely come into play for the professionals such as one on the twelfth hole. “On number twelve, we added a bunker and then a mound on the left hand side further down from where you drive it,” said Crenshaw. “To watch these guys play now, it’s unfathomable to think that a ball can be hit that far, but it can.”

A similar bunker (although not original) was added beyond the right side of the landing area of the following hole as well. “We added one bunker to the right on thirteen,” Ben mentioned. “The bunker is meant to be entertained obviously for the long hitter. It’s sort of a sneaky bunker. You can’t really see it greatly off the tee but you’ll know it’s there once you play it.”

Number seven has always been the bugaboo in Ross’ routing, mostly because it is the only hole on the course he re-routed back in 1923, converting from its original straight direction to a hard dogleg right for the new fifth hole (at the time). Ross himself, Richard Tufts and Billie Joe Patton, Peter Tufts, George and Tom Fazio, Rees Jones, and now Bill Coore and Ben Crenshaw all worked overtime to figure out how to make the corner of the dogleg more risk and less reward.

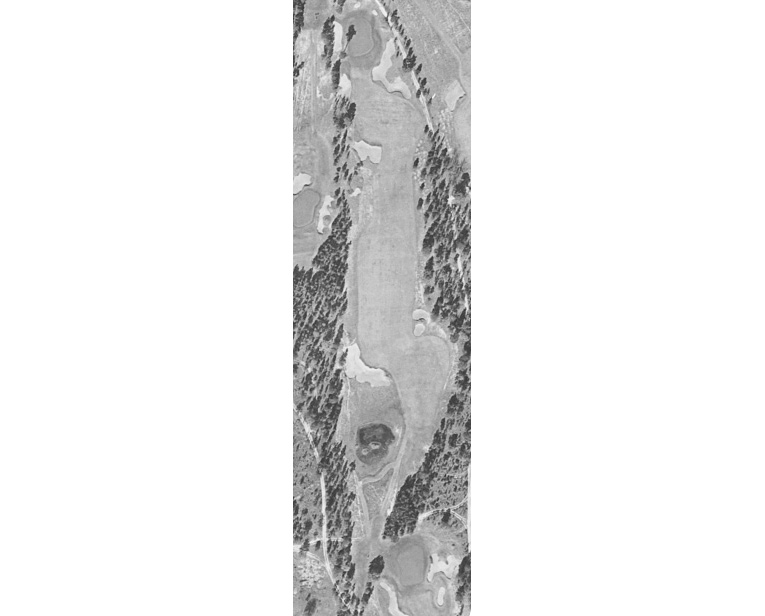

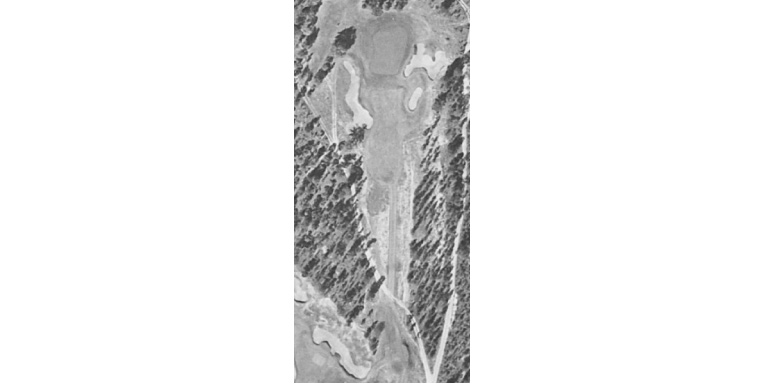

One of the biggest beneficiaries of the restoration was the seventh. Above is how it looked in the 1930s and below …

… is how it looks for the 2014 Opens. In the 1960s, the crook of the dogleg had shrunk down to fifteen yards in width, a very un-Ross feature.

They all fought the increasing golf ball distance in the process. After the initial Bermuda removal, Coore and Crenshaw, with a little prodding from Mike Davis, brought the outside (left side) corner of the dogleg toward the center an additional ten to twelve yards. They replaced a series of mounds added by Tufts and Patton for the 1962 U. S. Amateur with a depression on the outside corner as well.

At the inside of the dogleg, three new bunkers were added beyond the four that were already there, forcing a tee shot of almost three hundred yards. Each one will have the steepest sand faces of any bunkers on the course, further injecting risk for those determined to cut the corner.

On the scorecard, the golf course will play 7,485 yards for the men and 6,800 yards for the women. As in 1999 and 2005, par will still add up to 70, but with one difference. For the first time ever, the fourth hole will play as a par four. In addition, the fifth hole will play as a par five. During the 1936 PGA Championship, both holes played as back to back par fives. In 1949, five was converted to a par four. At the same time, the eighth hole was changed from a four to a five, due to claims that the eighth hole was too difficult as a par four. The PGA of America kept the new par values for the Ryder Cup in 1951 and they remained that way for visiting golfers and members ever since. This demonstrates how the concept of par is nothing more of a mental hurdle for golfers of all abilities. In the 1951 Ryder Cup program, Dick Chapman noted:

“It has been interesting to note the psychological difference which has taken place among the tournament and visiting golfers since the par for the fifth and eighth holes was reversed two years ago. The fifth used to be a fairly easy par five, where many fours were made. On the other hand, the eighth was an extremely difficult par four, where only the longest could hope to get up in two. As a result, very few fours were made. Strange, now that the par has been changed, fours are much less frequent on the fifth, and more abundant on the eighth.”

When professional tournament golf returned to Pinehurst in the nineties, the distance of the golf ball necessitated that the eighth hole be converted to a par four for the pros, yet the fourth and fifth holes remained unchanged for professional events, playing as a par five and four respectively. For both previous U. S. Opens, the fourth hole was ranked eighteenth in terms of difficulty and the fifth hole ranked first in difficulty.

The reason for the switch was not historically-based (although history does provide precedent) but mostly based on how those holes are designed and respond to the professional golfer of the twenty-first century. Opportunity arose to strengthen the fourth hole when Coore and Crenshaw re-established the angle of play by the elimination of rough. When they returned the back tee to the left of the restrooms, they made the angle of play much more challenging, yet shorter as well. That combination move made for a much stouter par four (it will play 510 yards from the tips).

As a par five, the fifth hole will be stretched more than one hundred yards longer (590 yards) than it played as a par four in 2005. Its blind tee shot, uphill approach shot and much more difficult putting surface will transform what was previously one of the toughest par fours in Open history into one of the toughest par fives in Open history to reach in two shots. The fifth hole is now a dangerous problem for anyone flirting with the left side to get home in two as all of the Bermuda rough is now gone. Previously a ball would nestle in the rough; now a hot hook can easily end up on the edge of the fourth fairway.

STRATEGICALLY SPEAKING, THE MOST IMPORTANT ASPECT OF THE RESTORATION OF PINEHURST NUMBER TWO IS A RETURN OF THE VARIETY OF ANGLES OFFERED TO THE GOLFER FROM HOLE TO HOLE. Risk and reward have been reinstated as Donald Ross intended so long ago. One great example of this is the eleventh hole. Players now stand on the tee and have to make a choice of which side of the fairway to favor whereas before the narrowness provided only one route. Depending on which side of the green the flagstick is in, the golfer now can choose to play for the contrasting side of the fairway off the tee.

To Pinehurst, Inc. the restoration of Number Two seemed like quite a gamble considering the course’s appearance as a prototypical U. S. Open site. Almost all Open venues go through a renovation prior to an event but rarely do they stray far from their initial appearance. Usually it is adding length, re-grassing greens, or moving bunkers, all with the focus on the professional golfer.

But in Number Two’s case, the project was a transformation that was never attempted before and would result in a venue that was anything but prototypical for a USGA event. The hiring of Coore and Crenshaw was logical considering the team’s design philosophy and talent but it also was a safety net of sorts. In case things went wrong, the reputation of Bill Coore and Ben Crenshaw would certainly help to sell the golf world on their work.

That sell job wasn’t needed as the project came along at a time in the industry where returning to the roots of the game is just what is necessary to keep the game alive. “Nobody who you value came out and said ‘you guys are out of your mind, you are screwing this golf course up.’ Nobody ever said that,” recalled Padgett. “Everybody said, you know what, it looks like crap right now and you are tearing out these fairways and all this turf, but it’s going to be really good in the end,” he said. When Tom Fazio visited the project during construction he gave Padgett the thumbs up saying, “This is absolutely the right thing to do.” “When people like [Fazio] tell you that, it helps,” Padgett said.

In addition to the positives of less irrigation, less manicured turf, and more visual contrast, the new course will put a spotlight on shot-making and not brute strength. “Number Two has always been my favorite and I can think of no finer or more suitable one for a Ryder Cup match,” said Dick Chapman in the 1951 Ryder Cup program. “Although inland, this famous championship layout offers all the problems of a British seaside links.” In 2008 that really couldn’t be said, but now it has never been more true.

AS THE GOLF WORLD CHANGED FROM ALL SYSTEMS GO WITHOUT A CARE IN THE WORLD REGARDING COSTS, PLAYER RETENTION, OR MAINTENANCE CHALLENGES TO ONE WHICH HAD TO ADDRESS THOSE VERY ISSUES IN ORDER TO STAY RELEVANT, THE HOME OF AMERICAN GOLF, PINEHURST, HAS RECOGNIZED THAT A RETURN TO THE PAST IS SOMETHING THAT WILL ENHANCE ITS FUTURE. Restoration work such as that at Pinehurst Number Two have helped set a new trend of golf course architecture and development.

More importantly, common sense approaches toward golf course management in turf reduction, ratcheting back the need for perfect conditions, and simply recognizing that matching the correct grass for the correct environment will make the game more enjoyable for the golfer and the operator in the Sandhills as well as the rest of the world. Once again, Pinehurst finds itself setting the trend for the next century.

EPILOGUE 2013

THE FUTURE IS NOW

“What he found in the Sandhills of Pinehurst was rolling sand spotted with wild ‘wire grass’ indigenous to the region. After a rainstorm, or a windstorm, pine cones and straw grass were naturally strewn about. Since the Chinese army wouldn’t be enough manpower to pick it up, he simply left it there. Why not? It was utterly natural.” – Charlie Price

“NATURE ABHORS A STRAIGHT LINE.” The famous nineteenth-century landscape architect, William Kent, was most likely referring to an uninspiring landscape of rectangular beds of plants all dressed in perfect rows, connected to nothing which surrounds them, nor to each other. If he were a twenty-first century golfer, he would most likely be referring to all the golf courses out there that are a monoculture of boredom, with hazards set up to do nothing but garner visual attention, yet without any connection to their surrounds or each other, much like what Pinehurst Number Two looked like until recent events.

Variety, randomness, and intrigue are the terms that first come to mind when I walk the restored Pinehurst Number Two course today. The course is a far cry from the monoculture existence it inhabited for so long. When the executives of Pinehurst, Inc. and others first undertook the unmasking of Pinehurst Number Two, the apprehension was great. In their minds, they were risking the status quo. Almost nobody, especially most critics, considered Number Two broken by any means. Golfers still filled the tee sheets as long as there was space. It was a very profitable 170 acres.

Pinehurst Number Two was a model that the world accepted and endorsed. Golfers took what they witnessed on television during professional events at Pinehurst and elsewhere and made that a standard for the past half-century. That standard led to private clubs adopting unrealistic maintenance practices, individual owners seeking out ways to attract players solely through aesthetics, and the industry selling a product that clearly wasn’t sustainable, frankly more so from an economic standpoint than an environmental standpoint.

So why put the golfing world on its side? Why risk scrutiny and the wrath of armchair architects? Why change? Because it had to happen. This work to Pinehurst Number Two had to happen not just on a local scale but on a global scale. The pendulum swung too far to the wrong side. Although it took more than fifty years to swing, the pendulum of artificiality in golf reached its nadir at Pinehurst and everywhere else. A bigger problem was that few people validated the crisis. In 2009, I studied the feasibility of transforming Number Two’s Bermuda roughs to a more natural state. “Setting the trend, preserving the Ross legacy, and expanding the Sandhills ecosystem” was my tagline for the project, all benefits for all involved. A fourth benefit will be returning the game to its rightful perch. In other words, the recent efforts at Number Two go beyond just setting the trend. They validate the future.

The stage Pinehurst Number Two sits on will be the answer many are looking for in terms of the game of golf moving forward. It is crucial that the professional golfer falls in love with the restored product. The course setup flies in the face of what the golf professional seeks in his work – a direct, delineated path from start to finish in order to shoot the lowest score possible. Yet Tiger Woods’, Phil Mickelson’s, and Rory McIlroy’s predecessors, Walter Hagen, Byron Nelson, and Ben Hogan, all faced the challenges Number Two now presents on a regular basis. They sowed the seeds for the professional golfer of today in the process. The game’s past legends adapted. Now is the time for the game’s present legends to adapt.

What will the professional golfer find when they step onto Pinehurst Number Two? Many will find frustration, confusion, and confrontation. Sandy lies that vary in composition from point to point within arbitrary twenty square-foot areas will do nothing but frustrate the pro golfer, especially under the stress of a U.S. Open. Further complicating matters, randomly placed wiregrass plants within the sandy native areas will create extreme unpredictability for the best golfers in the world.

Gone is the consistency of uniform rough. Golf shots from sandy pine straw are more challenging than from rough due to the possibility of slipping feet or the ball moving at address. It is akin to playing a bunker shot without grounding your club, but picture the sand as ice. There is much more randomness in that than balls nestled snugly in sand or deep rough, where the golfer knows it isn’t going anywhere. Ironically, those conditions are what the origins of the game are all about in links golf – unpredictability. That unpredictability and the challenge to overcome what the golfer found is not only character building, it is compelling to experience.

Yet the professional golfer will also find intrigue, challenge, and distinctiveness. The adoration for Number Two was evident among the pros in the recent past. They waxed eloquently about playing the course, remarking that it was one of a kind and something they didn’t see on a weekly basis. But it was a false-positive. Beyond the perched greens, they saw the same narrow fairways, same deep rough, and same irrelevant bunkers each and every week in other corners of the world.

The return of Pinehurst Number Two to its more natural state and the worldly stage it sits upon will help bring the game back from its economically-induced slumber and teach all of us about character building. Regardless of venue, the construction, maintenance, and operation of a course such as the model of Number Two is more sustainable in all realms. Wide fairways and no traditional rough is also a model of playability (and strategy) for the recreational golfer, which is most important for the sustainability of this game.

If operators and owners of the most obscure golf courses (and there are many) can adapt their venues to move away from a green monoculture and closer to the natural variety and randomness that golf was founded upon, their business will succeed and the game will thrive. That said, it is the golfer that must accept this example. They will look to the professional for validation. Hopefully it will be given.

What the professional golfer now sees is one of a kind. As long as they embrace their senses, then Pinehurst Number Two will certainly set the trend. As long as validation is present, then the work undertaken can go beyond just a success for the resort; it can be a model for the golf industry to follow and the golfer to embrace.

Pinehurst Number Two is the stage and major championship golf is the script the golf world needs to embrace the future. Pinehurst Number Two is not just the future of golf in the Sandhills, it is the future of golf everywhere in one form or another. That future is now.

THE END