Tillinghast: Student of Golf Course Architecture

by

Philip Young

July, 2014

The Golden Age of golf is a phrase easily said today. Looking back, we recognize this as the time during the first few decades of the 1900s that the game became a world-wide passion. A key reason was the sudden emergence of notable golf courses across America that could be compared to the great courses of the U.K. Courses like National Golf Links of America, Pine Valley, Merion, Baltusrol and Pinehurst No.2 that were immediately recognized as world-class and remain so to this day.

An especially important year in this era was 1911. CB Macdonald’s NGLA and AW Tillinghast’s Shawnee opened for play less than 4 months apart. For these two towering figures of the Golden Age to have seminal courses open so close together is more than coincidental, for both spent time in the U.K. in the years before this studying the classic courses on that side of the pond. Both took what they learned and formed philosophies of design, albeit in decidedly different ways.

This essay has two purposes. First, to detail that time of study for Tilly and see how he inculcated what he learned into his designs throughout his long career. Secondly, to announce the discovery of a true architectural treasure that has lain hidden in a case and under an apron both adorned with the symbol of the Mason’s order. The treasure is two original hand-colored hole sketches done by Tillinghast, one from 1899 and the other 1901. Neither has been seen in public for more than 80 years.

They hint at many possibilities about that Golden Age of Design and are sure to become the source of much conjecture and heated arguments regarding what they might mean and prove. There is little doubt that they reveal heretofore unknown details about the young Tilly and his passion both for architecture and playing the game. But just as amazing as the discovery of these drawings is the story of the man who was given them and why they’ve been out of sight all this time. So let’s go back in time and see where this tale takes us.

An Architect’s Beginning

In 1896, the 21-year-old Tilly travelled to St. Andrews for the first time, just a few years after both he and his father took up the game. They would become founding members of the Belfield CC. Tilly became entranced by the town, the people and the legendary players he met in St. Andrews, especially Old Tom Morris.

A few years later, Tillinghast wrote, “I met him in 1896, and although I never saw him again after 1901, he did write me several brief notes… When golf first made its appearance in America in the early [18]90s, we pioneers in this country spoke almost in muted tones of reverence when the name of Old Tom Morris of St. Andrews, Scotland, was mentioned. To us he was nothing less than the patron saint of golf. As a matter of fact Old Tom was also regarded thus in the old country. Consequently, when I soon after came in contact with him, face to face in his wee shop, just off the home green in the City, Auld and Gray, I really felt that I was standing in the presence of the High Priest in the Holy of Holies. This was about 1896 and I had not been so long in the game. Here was a man, in his eighty’s, who for a generation had been held in veneration throughout golfdom.”

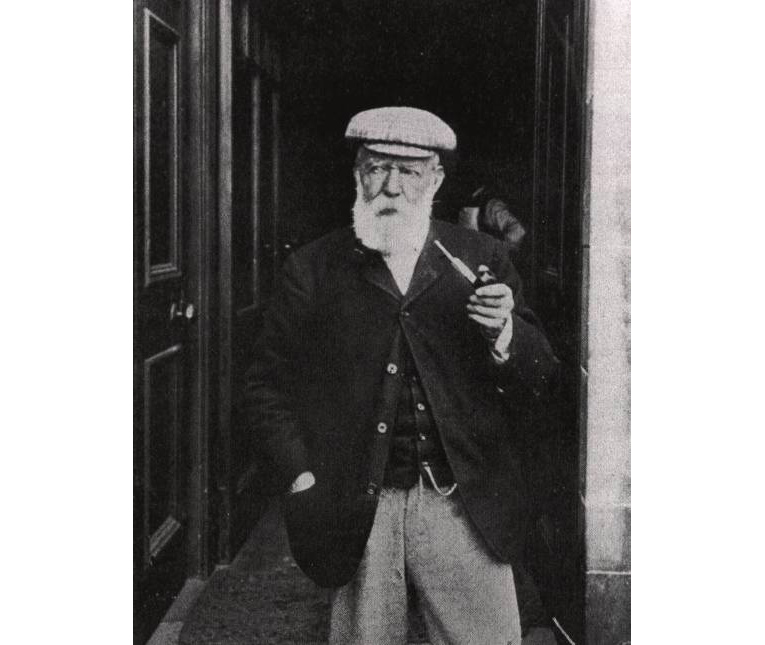

It was during his trip over in 1898 that Tilly took what is considered the iconic photograph of the grand old man. He recalled how, “At the time when the photograph was taken we had been chatting in his shop and I happened to have with me my ‘Lantern’ as Andra Kirkaldy used to call my camera. Old Tom was not at all inclined to pose for photographs but I cajoled him to the open shop door. This fortunate likeness was the result, for he declared it was the best ever made of him…”

For Tilly going to St. Andrews was a near- religious experience. He wrote, “As the train neared St. Andrews, that Mecca for golfers, and I noted the gradually increasing numbers of the faithful, I marveled that the popularity of the ancient game had continued, unabated throughout the centuries…

“Once in St. Andrews one revels in golf. He is a slave for the nonce. He is in a new world – a new being. The atmosphere of the old town is redolent with golf. The very tots amuse themselves with miniature golf clubs, which take the place of the usual toys so dear to the ordinary child.”

Following his 1898 trip, Tillinghast did something remarkable, which he wrote about 10 years later. “I was invited to run out to Frankford, a suburb of Philadelphia where at that time golf had yet to be introduced. Selecting the most available ground (which, by the way, is almost on the links of the present Frankford Country Club), I laid out a rather crude course, using for holes, tin cans which had once contained French peas. With a group of curious, skeptical citizens around me I next proceeded to demonstrate the various strokes to the best of my ability until one of the spectators expressed a desire to try his hand at it…”

Today that first rudimentary attempt to design a golf course is the site of Frankford High School.

Read Tilly’s words again. He had been, “invited to run out to Frankford,” likely meaning, and this would be so like Tilly, he probably had been speaking about the courses and players in the U.K. to such an extent that he appeared to the untrained Americans ‘expert’ enough to lay out a golf course where the game could be taught to the public. We can also be rather sure that he spoke of the specific details of the courses he had visited, so he already must have begun studying them and sketching individual holes.

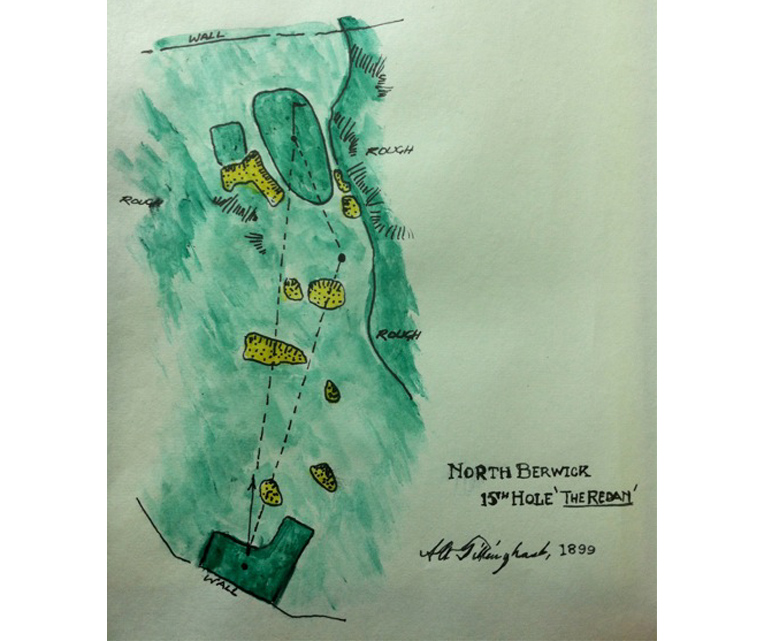

Throughout his life, Tilly carried his 5×5 camera and sketchpads he drew golf holes that he saw and others that he conceived while he studied the land before him. Here is one of those sketches drawn in 1899:

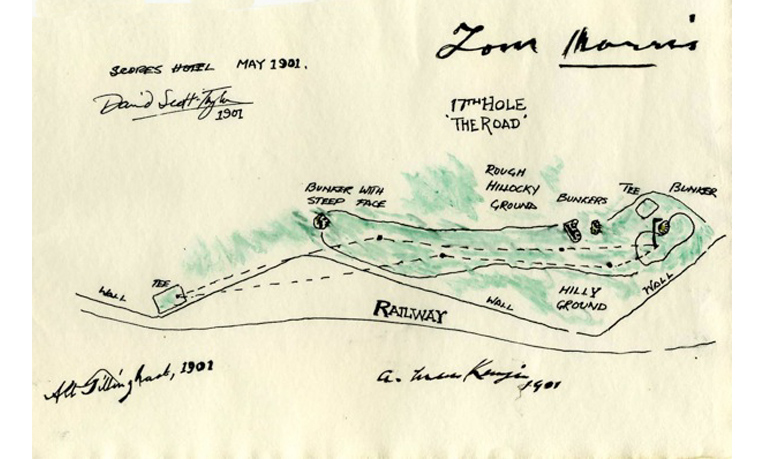

And this sketch, which he drew in May, 1901, is beyond remarkable. Not only is it of the Road Hole, it is the only piece of paper known to exist that bears the signatures of these three giants of the game, A.W. Tillinghast, Alister MacKenzie and Old Tom Morris.

These prove that not only was Tilly studying golf course architecture during his travels to Scotland, he also brought back numerous sketches of the great individual holes that defined architecture then and now. Furthermore, they prove that Tilly sketched these holes several years before CB Macdonald traveled to the UK to study the great holes in preparation for his master design at National Golf Links. In these sketches we see the principles that he incorporated into so many of his own designs. It also helps one understand when he disagreed with Macdonald’s use of these as “template holes” forced onto land. Tillinghast believed that a proper design incorporated the features that the land gave the architect and by putting a hole based solely on a template on ground that didn’t naturally allow for it defeated the purpose of the design itself.

Tilly maintained a lifelong friendship with the man he called “Charlie”; he also was a fan of a number of MacDonald’s courses, praising them in his writings. Yet he staunchly believed that the best designs were those that fit the land on which they lay whether they would support a “template hole” or not. It also proves that Tilly was not a MacDonald disciple as some have claimed based on his using features and hole types from UK courses. In true fact, Tilly did the studying himself and put into practice only those principles that he believed represented great course design.

The discovery of these sketches also leads to careful consideration as to how these sketches might have been used by Tilly, as well as their effect on others at that time. We know that Tilly was well liked in his day by golfers and golf experts on both sides of the Atlantic. He was already considered quite knowledgeable about golf course design and construction at the turn of the 20th century. A vivacious and outgoing young man, it is impossible to believe that he wasn’t showing his UK sketches to any and all of his friends. Among these was a fellow Philadelphian, Hugh Wilson.

In the debate over how Merion was first designed and built, the tale told of Wilson’s trip to the UK and his return with sketches of the great holes was shown to have been a mistake. He wouldn’t make that trip until after the course was built. What then could have been the source of this misinformation? Could it possibly have been the Tillinghast sketches of these holes?

Tilly was outgoing and was becoming consumed by his growing passion for course design. He loved showing his sketches and even gave some as gifts to friends. (Which is what happened with these two drawings, as we’ll soon see.) It seems very likely that Tilly showed these to Wilson, maybe even lending them to his friend when they were talking about how the new Merion course would be designed. We know that Tilly had a great deal of inside information as to what was going on behind the scenes at Merion because he wrote in detail about it. That information had to come from somewhere and it’s most likely that it came from his friend, Hugh Wilson.

So it’s reasonable to assume that when the tale of the design of Merion was told many years later, that the knowledge that Wilson had consulted design sketches of the great holes of Scotland and knowledge that he had gone over himself to make them, have as their genesis the Tillinghast hole sketches. This is not a dogmatic statement, but reasonable conjecture based on the proven existence of sketches of this type by Tillinghast and knowledge that it was his practice to share things of this type with his friends.

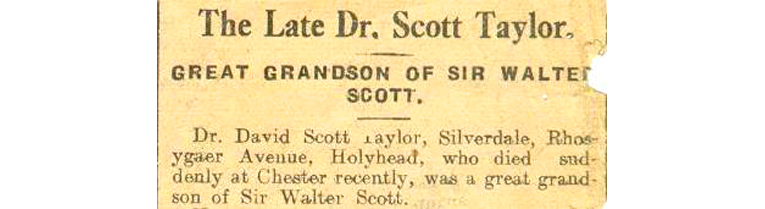

David Scott-Taylor

Look closely at the sketch of the Road Hole and you’ll notice a fourth signature, that of David Scott-Taylor. Who he was and why is he part of the gathering of golf’s titans in May, 1901? He was the man who brought them all together. Scott-Taylor’s story begins more than two centuries ago. Sir Walter Scott, noted Scottish writer, did what so many have done throughout time, he had an affair, ironically with a woman whose last name was also Scott. From this tryst came an unexpected son that, because of the mores of the time, could not be recognized as being his. He would be raised under his mother’s name which, after her marriage to a local blacksmith, became Scott-Taylor. In 1874 he had a grandson named David. It was at his unexpected death in 1933 that his true heritage was publicly acknowledged. But by that time he’d had quite a life of his own.

Born in India, David was brought to Scotland at the age of six to receive a proper education. In time he would go to medical school, become a surgeon and enlisted in the British Navy where he served as a ship’s surgeon. It was in that capacity in January, 1901, that a most unexpected event occurred. It was the first of a series on unexpected events that year; each in its own individual way would change the course of his life. Christmas Day 1900, once again found Queen Victoria vacationing at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight, a practice that she had done every year since the death of her husband, Prince Albert, on December 14, 1861.

The 81-year-old Queen suffered from rheumatism in her legs rendering her lame and her eyes were clouded by cataracts. By early January she was feeling weak and unwell and growing increasingly drowsy, dazed and confused with each passing day. The public was unaware of her deteriorating condition.

For those serving her at Osborne House, the Queen’s illness was more than a national crisis. Near the end they realized that a doctor was needed and quickly. At the time her personal physicians were back in London which created a dilemma, for only a physician with a high standing could examine the Queen and there were none on the island. At that time there were several naval vessels assigned to protect the Isle of Wight and the Queen. A call went out for a physician from one of the ships to be sent to Osborne House immediately for a physician in the Royal Navy automatically had the standing to examine the Queen. And so, without being told why or who he was going to see, Lt. David Scott-Taylor was shuttled over and immediately shown to the Queen’s chambers. He would attend the Queen while awaiting the arrival of her physician’s. The Queen quietly died in her sleep on January 22nd.

It was because of his support of the actions of the court officials and the Queen’s personal physicians that this formerly unknown naval surgeon gained the regards of many at the highest levels of the government and his reputation as both an officer and a gentleman rose dramatically over-night. Among the privileges to come the way of this young man who passionately loved golf was acceptance into the R&A as an unofficial member where he was welcomed at the club and its luncheons, dinners and events.

It was in May, 1901 that Scott-Taylor met up with another friend at St. Andrews, A.W. Tillinghast whom he’d met and befriended several years before. In 1899, the young American golf enthusiast gave the young doctor a sketch of the famous Redan hole at North Berwick that he’d drawn during that year’s trip to Scotland.

In St. Andrews, Tilly gave a new sketch to his friend, one that he’d just finished of the Road Hole. Scott-Taylor was so excited by this that he walked into Old Tom Morris’ shop and asked the grand old man to sign it for him. Old Tom replied that he would be happy to do so but that it would cost the price of a dinner. So he invited Old Tom to meet him that evening at the restaurant of the Scores hotel. He then invited both Tilly and Mac (the nickname he called him throughout their lives) along as well. It was at that dinner that all four of them signed the sketch.

The conversation that must have taken place, the stories and history of the game shared, maybe even a debate over architectural principles. The possibilities of what might have been talked about, is both endless and awe-inspiring. That it was a memorable and enjoyable evening for all goes without saying as does the desire of every person who has ever loved the history of both the game of golf and course architecture to be able to have listened in.

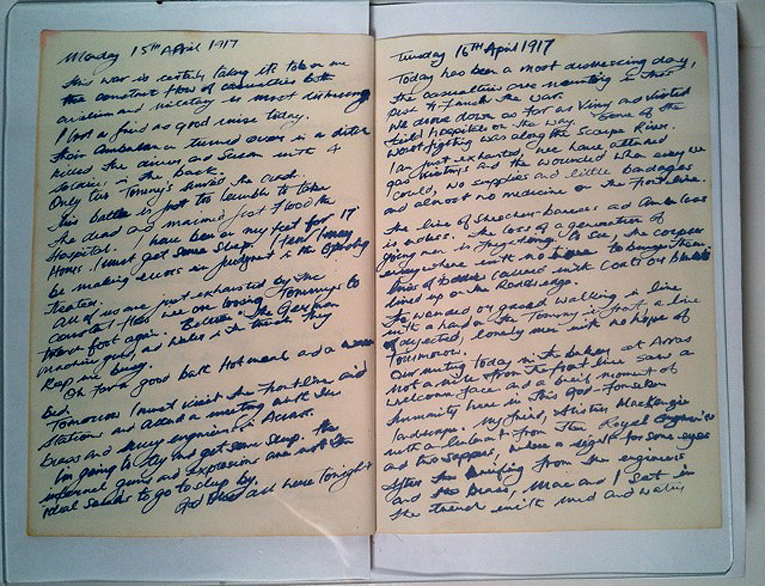

Where can this information be found today? It comes from another treasure from Dr. David Scott-Taylor, his personal journals in which he wrote nearly every day of his life, even while serving in the trenches as a surgeon during WW I. These journals are in the possession of his grandchildren from whom I’ve been given the privilege of seeing the actual drawings and having the information found in a number of these journals shared with me.

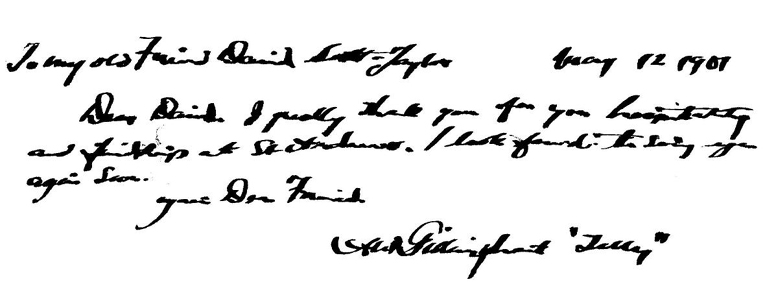

In the journal which detailed this gathering was found another priceless treasure, a thank-you note written the day after the dinner on Score’s Hotel letterhead thanking his “old Friend David Scott-Taylor” for the evening they enjoyed the night before signed by Tilly.

The journals of Dr. David Scott-Taylor are deeply moving and filled with information that give a rare first-hand insight into the personal lives of a number of the greats in the game of golf along with other famous friends of his. Below is a photograph of two pages from his journal dated April 15 & 16, 1917. If what is written here doesn’t move you than nothing in life will. It reads:

“Today has been a most distressing day, the casualties are mounting in this push to finish the war. We drove down as far as Vimy and visited field hospitals on the way. Some of the worst fighting was along the Scarpe River. I am just exhausted, we have attended gas victims and the wounded whenever we could, no supplies and little bandages and almost no medicine on the front line. The line of stretcher-bearers and ambulances is endless. The loss of a generation of young men is frightening to see, the corpse’s everywhere with no time to bury them. Lines of bodies covered with coats or blankets lined up on the roads edge. The wounded or gassed walking in line with a hand on the Tommy in front, a line of dejected, lonely men with no hope of tomorrow. Our meeting today in the bunker at Arras not a mile from the front saw a welcome face and a brief moment of humanity here in this god-forsaken landscape. My friend, Alister MacKenzie with a lieutenant from the Royal Engineers and two sappers, where a sight for sore eyes. After the briefing from the engineers and the brass, Mac and I sat in the trench with mud and water all around. The sound of distant guns and the eerie silence in between made for a serial backdrop to a conversation of home, hopes and laughter with a dear friend. Never has a flask of my whiskey and Mac’s cigarettes tasted so good. I wished that it would never end this hour, a precious hour in time of war. Mac heads home tomorrow, back to England, while I must stay to do my duty. Help what little I can to ease the pain and suffering of these poor souls here. God bless all this night in this hell.”

It is my honor and privilege to have gained both the trust and friendship of Ian Scott-Taylor, a grandson of Dr. David Scott-Taylor and a golf course architect in his own right, as well as the rest of the Scott-Taylor family. They’ve given me permission to share this “discovery” with you, although to them it’s their family legacy and no “discovery” whatsoever. The two sketches of The Road Hole and the Redan will be displayed on the USGA’s golf course architecture initiative website.

The End