George Arthur Crump: Portrait of a Legend

by Thomas MacWood

March, 2005

As you near the tiny station, a lone figure standing on the platform can be seen from the train window. A medium-size man with a blocky build, he insists on greeting everyone out for a game. Wearing imported knickers and a white cap, his two hunting dogs at his side, he warmly greets you as you step off the train, pats you on the back and leads you through a gate, above which is a sign: ABANDON HOPE ALL YE WHO ENTER HERE.

Some of the greatest names in the game have walked through that gate. George Thomas called Pine Valley the acme of golf. Alister MacKenzie said it was by far the most spectacular course in the world. Bernard Darwin said it was ‘a wonderful course, wonderfully beautiful, and wonderfully difficult.’ Donald Ross declared it the finest in America long before it was finished. Tom Simpson said for sheer beauty and all around excellence it had no rival among inland courses. Robert Hunter claimed Pine Valley is the only course in America that is loved and pictured as a thing of structural beauty. CH Alison said it was the best course he had ever seen. Max Behr believed when completed there would be nothing like it in the world. Grantland Rice maintained Pine Valley came as close to being a flawless test as the imagination could devise. AW Tillinghast said it was undoubtedly the greatest golf course on the continent, that it reflected the genius of one man and ‘must ever be a tribute to his memory.’

That man was George Crump. Pine Valley and Crump are synonymous. From its inception, the New Jersey course has been hailed as one of the greatest courses in the world, and one of the most demanding-a universal reputation bordering on the mythical. But while this storied golf course has had volumes written about it, we know relatively little about its founder beyond a narrow legend, certainly not a complete picture. We hope to correct this slight.

Born in Cheltenham, England, William Hawkins Crump migrated to Philadelphia in 1838 to take a position as editor for the Philadelphia Inquirer. His family consisted of a wife Anna, sons Morris, Robert and John, and a daughter Emily. Within their first three years in Philadelphia, Mr. and Mrs. Crump had another two sons-George W. and Albert. The family eventually settled in Camden, just across the Delaware from the Quaker City.

Of the sons, Morris Crump attended medical school before moving to western Illinois to practice medicine. Robert Crump was listed as an artist in 1850, but then vanishes-a return to England and the Civil War are possibilities. The youngest son Albert Crump became a carpenter, had modest success, but died young. The two remaining sons, John and George W. made names for themselves in Philadelphia.

The eldest son John went off to Ohio in order to learn the trade of carpentry. After returning, he enjoyed considerable success as both an architect and a contractor. John Crump was responsible for the design and construction of a number of local landmarks, including as contractor, the Union League Building and the University of Pennsylvania Hospital and as architect, the Commercial Exchange Building and the Atlas Hotel.

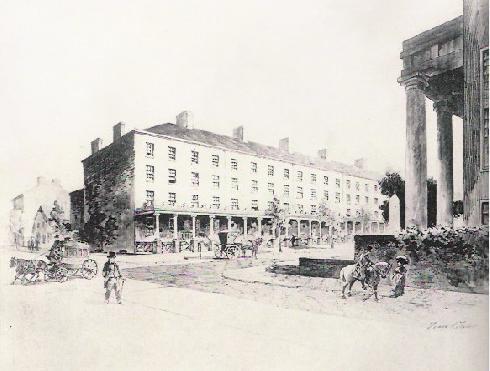

John Crump also entered into the hotel business-designing, constructing and then managing the Colonnade Hotel. The Colonnade would become the social hub of Philadelphia in the decades after the Civil War. John and wife Jane had four children, two daughters and two sons. The two sons-Henry J and George R-would follow in the father’s footsteps.

The Colonnade Hotel.

George W. Crump was the first of William’s children born in America. He was educated at the University of Pennsylvania, receiving a degree in Law. After graduation, he served as Secretary to the British Consul in Philadelphia, before being elevated to Vice Consul in 1868-a position he held for the next twenty-three years, until his death. GW Crump was well known in social circles, both in America and Britain. Crump and wife Elizabeth had four children, two boys and two girls. George Arthur Crump was their second child.

The George W. Crump family lived in Camden before moving to nearby Merchantville, NJ and a large Stick Style home (This home is currently listed on the National Register of Historic Places). Mr. Crump was a lover of outdoor pursuits-especially hunting and racquets sports-a passion he passed down to his children. Daughter Helen was a nationally respected tennis player and son George A. competed in regional squash events.

Crump’s diplomatic career was for the most part stellar with the exception of an unfortunate international incident in 1881. A report he forwarded to the British Government, stating hog cholera was prevalent in the United States, found its way into The Times. Because the US was a major exporter of pork, the report-which turned out to be false-set off a firestorm on both sides of the Atlantic.

Secretary of State Blaine lodged a formal complaint with the British, and a committee was formed to investigate the origins of the ‘Crump canard.’ Ultimately it was found the report was based largely on exaggerated statistics from a Chicago source. Unfortunately the controversy may have cost Crump the Consul position, which was open, he had been acting Consul at the time of the report. Undeterred, George W. Crump recovered and continued to serve the British Consulate with honor and distinction.

He wouldn’t be the last Crump to face hardship. When John Crump retired in 1880 to his estate in Media, Henry and his brother George R. became the proprietors of the Colonnade Hotel under a lease arrangement with their father. They also became involved in the management of the Devon Inn, a fashionable summer hotel in Chester County leased from Lemuel Coffin. Unfortunately, the year after taking over The Devon it was destroyed by fire. An inauspicious start for the two new hoteliers, but thankfully the Inn was fully insured and rebuilt.

Regrettably trouble would again rear its head-this time in March of 1891. The headline in the NY Times read ‘The Crump Failure’. Forty of the brothers’ creditors had gathered in the office of their attorney John O. Bowman ‘for the purpose of being enlightened on the affairs of embarrassed firm. The notices sent out to the creditors stated that the Messrs. Crump found themselves in such financial condition that in order to continue the business some concessions were necessary.’ The Crump’s liabilities totaled $260,000, with assets of only about $80,000. The following week, in an article entitled Failures in Business, it was reported, ‘The creditors of HJ and GR Crump of Philadelphia, the embarrassed hotel proprietors, have agreed to give them ten years time in which to pay their debts.’

It is interesting to note John Crump apparently refused to bail out his sons, and presumably he had the means. Although not directly affected by his son’s financial disaster, the controversy must have been personally painful for John Crump. He would die the following year, oddly enough in the Colonnade. Two years later it was reported the ’embarrassed hotel proprietors’ made an assignment to settle their debts, perhaps bolstered by their inheritance.

No worse for the wear, the Crumps would rebound, expanding their hotel interests with the Beach House in Sea Girt and the Congress Hotel at Cape May, both in New Jersey. With their financial house in order, Henry, who like his father was an architect/builder, was able to return to architecture-enter George A. Crump.

George A. Crump was born in Philadelphia in 1871, but spent most of his formative years in Camden and Merchantville. He attended local primary and secondary schools before joining his cousins in the hotel business-he did not attend university. This entrée likely occurred around 1892, the same year his father died at the relatively young age of 53.

George married Isabelle Henry in 1898, daughter of Francis Henry of Warren a pioneer in the Pennsylvania lumber and oil industries. Belle Crump was noted for her charity work, especially for hospitals and societies for the prevention of cruelty to animals. Quietly she bought and cared for horses the Philadelphia Fire Department deemed unfit or too old for service. Mrs. Crump kept the horses at her father’s summer home-she was affectionately known as ‘the fireman’s friend.’

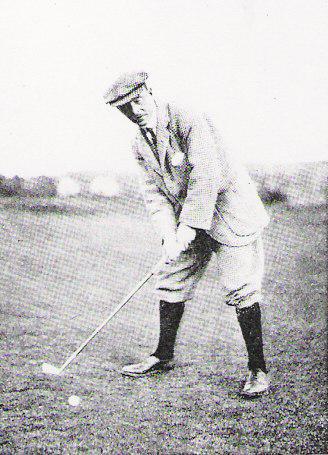

In 1900 the couple was living at the Colonnade, George listed his profession as the ‘Hotel Business’. The everyday management of the hotel was delegated to Eugene Lennard. With the hotel in capable hands, George was free to pursue other interests-especially golf. Crump had started playing in the late 1890’s-most likely at Philadelphia CC or the old nine-hole Merchantville course. Within a few years Crump was a full-fledged golf fanatic, eventually holding memberships at Philadelphia, St. David’s, Torresdale, Huntingdon Valley and Atlantic City CC.

In addition to golf, Crump was an avid squash player and member of the Racquet Club, as well as a devoted hunter of small game. A friend, Joseph Baker, estimated he had been on fifty hunting and golfing trips with George over the years. Through all these activities, it is not surprising Crump amassed a large circle of friends and acquaintances.

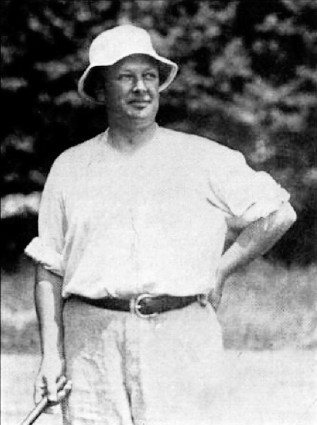

Crump the hunter resting in the wilderness.

Crump was described by friends as somewhat retiring, quiet and modest-he preferred to remain in the background. One gets the impression he was a man who could easily meld with a wide variety of personalities. Warm, kind, welcoming, generous, considerate and unselfish are all adjectives associated with George Crump. By all account he was a wonderful man-Nature’s nobleman is how one friend described him.

He also possessed a good sense of humor, which was on occasion self-deprecating. Another trait, often found with successful men, when he took on a challenge, he did so enthusiastically, almost to the point of obsession. Be it professionally or with a leisure activity like golf.

As an illustration of his single-minded focus, he developed into one of the better golfers in the city just a few years after taking up the game. He won the Patterson Cup in 1901, one of Philadelphia’s major championships, and became the club championship at St. David’s in 1903, 1904 and 1905. When in 1900 New York and Philadelphia entered into a series of intercity matches (a precursor to the Lesley Cup) Crump was a fixture on the Philadelphia team. The NY team, featuring Walter Travis, Findlay Douglas, CB Macdonald and Devereux Emmet, dominated those early matches. The first match in 1900 ended with New York on top 49 holes to 22, followed by two more lopsided wins, 54 to 11 and 75 to 3.

In the inaugural 1905 Lesley Cup, a tri-city match between New York, Philadelphia and Boston, Crump was once again representing his city. He was on the team in 1906 as well (Crump was a member of six Lesley Cup teams), but unfortunately Philadelphia did not taste victory in this format either. These early struggles would begin to weigh on Crump and the Philadelphians, eventually impacting future golf development in that city.

In 1906 Crump began construction on a stately Georgian-style home (including a carriage house and squash courts) in Merchantville-it was to be the couples dream home. Sadly Belle Crump would never live to see the home completed. That summer she and some friends went on three-week automobile tour of New England, during the journey home she began to feel ill. On the mourning of September 10th, 1907, Mrs. Crump boarded a ferry in Manhattan destined for Jersey City, while crossing she collapsed mid-river-she was dead before the ship reached the slip. George hurried up to Jersey City and brought the body back that afternoon. Her death was attributed to heart disease. When the couple’s dream home was finished the following year George’s widowed mother Elizabeth moved in.

No doubt this tragic loss had a devastating affect, and understandably Crump did not compete in the Lesley Cup that year, nor the following year, in fact his golfing activities seem to drop off during this period. But Crump was resilient, and the lull, thankfully, was temporary. By 1909 Crump reappears in all the major competitions, although his game had suffered a bit from the lay off.

A close group of friends would certainly lessen the pain, and few men had a greater group of friends, many he had met on the links. Their annual habit of traveling to Atlantic City every winter weekend is well documented. Philadelphia’s courses, built upon clay, drained poorly and the few playable months in the summer were not enough for the true devotees.

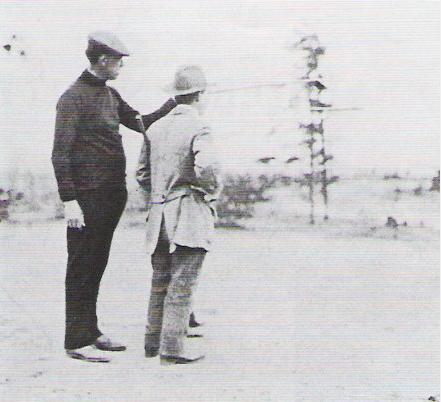

AW Tillinghast wrote, ‘Every Saturday morning the coterie of enthusiasts boarded the train, possibly leaving inches of snow at home, knowing well that the seaside course would be free of it and that the temperature was four or five degrees higher.’ These diehards included Crump, Tillinghast, Howard Perrin, Cameron Buxton, Robert Large, WP Smith, AH Smith and Wirt Thompson. And instead of playing a conventional two-ball or four-ball, if their numbers were less than a dozen, they’d play in a single huge group, which became known around the country as Philadelphia Ballsome.

George Crump disembarking at Atlantic City.

Around 1909 there were signs of a general dissatisfaction with the quality of Philadelphia golf. New York had dominated the Lesley Cup, winning the first five competitions. In fact this same year, the Philadelphia team became the Pennsylvania team in hopes an influx of Pittsburgh talent might improve their competitiveness.

Philadelphia golfers had not faired well in the US Amateur either-New York and Chicago had dominated. No Philly golfer had made it as far as the quarterfinals in the first fifteen years of the championship. These disappointing results led to some serious soul searching.

In article in The American Golfer Tillinghast wrote that the Philadelphia slump was a direct result of her deficient golf courses. They were not up to championship standards, and to make matters worse, the existing courses located near the city center were being squeezed by development. ‘Philadelphia must forget the convenience of links within her walls; she must be content to range a bit for her play. Does New York grumble because of the time it takes to go to Garden City, Nassau, Baltusrol or Englewood? Chicago makes light of the runs to Glen View and Wheaton. So my dear old Quaker town I believe that you too, must make up your mind to leave the city behind when you play. Go outside where you can buy your land, but select good golfing country for it, even though you have to take it to the sands of Jersey.’ He went on to say, ‘Go but a few miles away on the other side of the Delaware, where the sandy sub-soil is ideal…Let me quote a very prominent Philadelphia golfer, ‘We are past our babyhood in golf. Let us build permanent courses that are up to the standard of the best.”

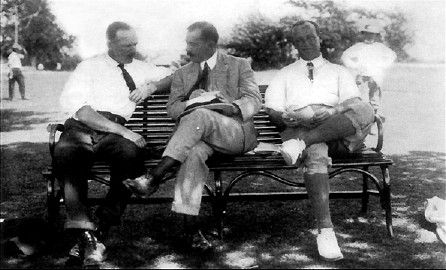

Three Philadelphia veterans: William Poultney Smith, AW Tillinghast and George Crump.

Over the next two years there were some glimmers of hope. Shawnee, about eighty miles north of the city, was very well received, Huntingdon Valley had undergone some upgrades and the new Merion course under construction held great promise-but Philadelphia had faired no better on the links (Massachusetts won the 1910 and 1911 Lesley Cups.).

Early in 1911, Tillinghast was at it again, ‘It is one thing to admit the past off-year of Philadelphia’s golf, but is quite another to explain it.’ He acknowledged the game was certainly popular in the city, it wasn’t a question of quantity, but quality. He reiterated his plea for better golf courses, ‘Give us some class courses, and we will produce class players.’

The following month, another local golfer William P. Smith was invited to offer his critique, he began by confessing he probably didn’t have the space to do the subject justice, but hopefully this self-evaluation would stimulate ‘a serious discussion in Philadelphia as to a means of overcoming the unfortunate conditions.’ He identified four primary reasons for their poor showing, they included the arrangement of too few serious matches and far too many casual ‘ballsomes’; a local golf association focused on politics and not on developing good golfers; the best players were busy businessmen; and last but not least, the fact that Philadelphia lacked any true championship tests.

It was this state of mind that sparked a reformation in Philadelphia, a concerted effort to upgrade her golf courses, to build championship courses to rival any in America, if not the world. This was the state of mind that inspired and motivated George Crump and his friends, resulting in Pine Valley, as well as courses like Merion, Oakmont and a long list of impressive designs.

One can discover quite a bit about a man by examining his friends. The men George Crump surrounded himself with shared a number of common characteristics. They all made their home in Philadelphia, they were all intelligent and well educated, and they were all very good golfers. But more than being just good golfers, these men were crazy about the game-all regulars on the winter excursions to Atlantic City. It wasn’t social status or business success that drew them together, some were wealthy, others of more modest means. The common denominator was golf.

Howard Perrin: Philadelphia Cricket & Merion. An excellent golfer. Won the Philadelphia Am in 1903 and 1906, the Patterson Cup in 1902 and won the Silver Cross three times. Played on 11 Lesley Cup teams (1905-1915). Served as President of both the Golf Association of Philadelphia (GAP) and the Pennsylvania Golf Association. Elected USGA President in 1917. Perrin a graduate of Princeton was in charge of the MA Hanna Company’s coal interest and VP of the Susquehanna Collieries Company. In 1913 he claimed to have undertaken a major share of the planning of the Pine Valley course. Perrin died in 1929.

Simon Carr: Huntingdon Valley. A Roman Catholic priest. First introduced to the game while attending the National Championship at Atlantic City in 1901. So impressed was Carr with the beauty of the game, he became a devoted student and soon developed into one of the better golfers in Philadelphia. Qualified for the 1903, 1905 & 1906 US Amateur. Won the Patterson Cup in 1907 and the Philadelphia Am in 1908. Played for the Lesley Cup from 1905 to 1909. A graduate of Catholic University with degrees in Theology and Semitic languages and a doctorate in Philosophy. His parents were Irish, his father died when he was a boy. Carr was said to be Crump’s best friend. He died in 1957.

William Poultney Smith: Huntingdon Valley & Philadelphia CC. A very good golfer, perhaps the best in the city in those early years. Won the Philadelphia Am in 1898, 1901, 1902. Won the Patterson Cup three times. Played on the Lesley Cup in 1905, 1906, 1908, 1910, 1911, 1912 and 1916. Smith was from an old Colonial Pennsylvania family. He was the Financial Manager for the enormous Cramp Shipbuilding Company. A graduate of Penn in Mechanical Engineering. Before becoming a manager, Smith was as a naval engineer and architect. Died in 1936.

AW Tillinghast: Philadelphia Cricket. Journalist and emerging golf architect. Designed Shawnee-on-the-Delaware in 1910-11. Won the Silver Cross in 1910. Runner-up in the 1906 Philadelphia Am. A member of five Lesley Cup teams (1905-1909). A colorful character who had a reputation for hard living. He was the primary chronicler of Pine Valley, but oddly doesn’t appear to have been a member of the club. Tillinghast claimed, after Crump’s death, to have designed the 7th and 13th at Pine Valley. One of golf’s greatest architects, Tilly died in 1942.

Cameron Buxton: Huntingdon Valley. An excellent golfer. Originally from Winston-Salem, NC, he picked up the game after moving to Philadelphia around 1907. Like Carr he was a quick learner. Won the Silver Cross in 1913 and the Philadelphia Am in 1916 and 1917. Played on the Lesley from 1911 to 1915. Moved to Dallas in the fall of 1916, and was instrumental in founding Brook Hollow (designed by Tillinghast)-an extremely challenging test along the lines of Pine Valley-designed to elevate golf in Dallas. Buxton died in 1926 while on a visit to Philadelphia.

Wirt Thompson and George Crump.

Wirt Thompson: Huntingdon Valley. Originally from St. Louis, Thompson moved to Philadelphia after graduating from Yale. Won the Philadelphia Am in 1910. Played for the Lesley cup in 1910, 1912 and 1916. President of the Pennsylvania Golf Association and an executive with USGA. Although involved in stocks and bonds, Thompson was not a wealthy man.

A. Haseltine Smith: Huntingdon Valley. Brother of Wm. P. Smith. A very fine golfer, Smith won the first Philadelphia Am in 1897, and again in 1911. He was a very active competitor in regional events. Played on the Lesley Cup team in 1912. Insurance broker and an associate of Haseltine Smith & Co. Smith claimed to have had a hand in the design of Pine Valley, Huntingdon Valley and Cobbs Creek. Tillinghast credited the Smith brothers with the concept of the ‘birdie’ on one of their sojourns to Atlantic City.

Robert Large: Huntingdon Valley. A 6-handicapper, Large didn’t have the golfing accomplishments of the others, although he had a handful of good showings. A coal traffic manager for the Penn RR. A regular on the Atlantic City trips. He died in 1917; he was only 42 years old.

Persons outside the inner circle, but who were selected to the first Pine Valley committee, no doubt for a unique expertise they could lend:

Herman Wendell: St. David’s. The oldest of the group, born in 1852 . A founder of St. David’s CC, Wendell was instrumental in developing the village of the same name. An architect, builder and prominent real-estate developer in Philadelphia. A good golfer, it was said he wouldn’t miss a single day without playing golf-snow or no snow. A regular on Atlantic City trips; he might deserve inclusion in the first group.

Joseph C. Clark: Sunnybrook. One of six defectors from Philadelphia Cricket who founded Sunnybrook. Also a founding member of the NGLA. A good golfer (9-handicap), he was not a factor in the major local competitions. Clark had a law degree from Harvard, and was a senior partner in the law firm Clark, Hebard and Spahn. A long time executive with the USGA (VP in 1911-12); he was the association’s legal council in the 20’s. Clark was a pallbearer at CB Macdonald’s funeral.

J Walter Zebley: Huntingdon Valley. A 10-handicap, and like Clark, he was not a competitive force on the Philadelphia golf scene. Zebley was a long-time executive for the Golf Association Philadelphia (GAP), and was likely brought on board because of his fiscal experience and abilities.

Frederick W. Taylor: Sunnybrook. An avid golfer of average ability. A brilliant man, internationally known as ‘The Father of Business Efficiency’- he coined the term scientific management. Devoted his last years to the study of golf turf in a truly scientific manner, particularly the construction of greens. He had converted his estate into experimental station. So far ahead of his time were Taylor’s theories, his methods continue to be applied today. An original member of the PV committee, for some reason he was excluded months later. He died in March 1915 from pneumonia.

The first officers of Pine Valley: H. Perrin, president; WL. Thompson, vice president; JW. Zebley, treasurer; S. Carr, secretary and G. Crump, chairman greens committee.

The directors: H. Perrin, WL. Thompson, JW. Zebley, S. Carr, G. Crump, JS. Clark, H. Wendell, F. Taylor, WP Smith, AH Smith and CB Buxton.

Pennsylvania Team-1909 Lesley Cup Back Row: H. McFarland, Howard Perrin, H. Townsend (secretary), W. Fownes, WP Smith, W. West, E. Giles, W. Pfeil (middle) Bottom Row: AW Tillinghast, Simon Carr, G. Ormsted, N. MacBeth (George Crump was a member of the team, but for some reason is not in the picture)

It is not known precisely when George Crump and his friends decided to pursue the building of a first-rate golf course, an all-season facility, playable when Philadelphia’s other courses were not. It may have been on one of their trips to Atlantic City or perhaps at a national event competing on one of New York, Chicago or Boston’s finer courses. Whenever the critical moment occurred, it is clear the idea had been building for some time.

What we do know, in about 1910-possibly before, but most likely after-Crump and his inner circle met at the Colonnade Hotel to seriously discuss the building of a golf course. Simon Carr recalled, ‘Some few years ago, a dozen Philadelphia golf enthusiasts met in the Colonnade Hotel to discuss the project of establishing a golf course in the Jersey sands…They desired a course where there would be practically no closed season throughout the year. In discussing the problem, they had the seaside in mind, chiefly the region about Atlantic City.’ The venue for the meeting makes it clear who was leading the charge.

By 1910 the Crump family was actively trying to sell the Colonnade. It is reasonable to conclude the selling of the hotel and the desire to create a dream golf course were not unrelated. Crump had lost his wife only four years before and his father had died at a young age without ever enjoying the fruits of his labor. These events had to have affected Crump’s thinking and ultimately his plans. The idea of designing something of merit may have also appealed to him, after all his uncle and older cousin had been successful architects as well as hotelmen.

Jerome Travers gives us some insight into his thoughts: ‘To him Pine Valley was the dream of a lifetime come true….In his later years, when he had prospered and found his notch in the world of business as a hotel owner of wealth and affluence, his eyes and heart turned again toward the wooden spot in which he found so much joy in his youth. George Crump told me of it himself. The vision of Pine Valley transformed into a masterpiece of golf architecture came to him on one of those exhilarating expeditions he was again making over its white-grained expanses and through its quail-inhabited thickets….He was middle-aged, a fair measure of his life behind him…he stood on the threshold of his life, free of responsibility, unburdened with the cares of the world…he had weathered better than most men, to retire from the strife before it was too late to enjoy the fruits of his independence.’

In 1910 the hotel was sold for $300,000 to Martin Greenhouse, a local real estate mogul and the Trump of his time. It is unclear who owned the Colonnade in 1910. Henry Crump, George R. Crump, George A. Crump and George’s mother Elizabeth Crump may have owned it individually or in some combination.

Later that year Crump and his friend Joseph Baker embarked on a three-month European tour in order to play and study the premier courses of Britain and the Continent. Their itinerary included rounds at St. Andrews, Prestwick, Turnberry, Hoylake, Sandwich, Deal, Princes, Sunningdale, Walton Heath as well as golf courses in France, Switzerland, Austria and Italy.

The fifth hole, Sunningdale.

In hindsight, Crump’s visit to the heathland near London must have been particularly inspirational. In addition to Sunningdale and Walton Heath, other courses he may have seen include Royal Mid-Surrey, Swinley Forest, Stoke Poges, Huntercombe, Woking, Worplesdon, and Coombe Hill. Seeing what was possible in the rough sandy country around Surrey may have altered Crump’s thoughts on where good golf was possible. While on the tour he wrote to his brother-in-law requesting he purchase a map of Camden County.

The American Golfer noted on his return, ‘Mr. George Crump has returned from an extended golfing tour in Europe and he was delighted with the courses in general. Mr. Crump is not only a very stubborn player-and a good one to when in form, but he is also a close student of the game..Mr. Crump considers the course at Sunningdale one of the very best in Great Britain.’ Sunningdale was the only golf course Crump singled out.

After returning Crump began looking for a suitable site. According to Simon Carr and Joseph Baker, initially he looked toward the sea. A site at Absecon was identified, on the coast near Atlantic City (where Seaview is today), but it was ultimately rejected because it was cursed with mosquitoes and they felt it was just too far from Philadelphia.

April 1911 HS Colt makes his first trip to North America, designing Toronto and CC of Detroit.

Once the seaside was ruled out, the region outside Camden was searched in every direction. At one point Crump considered a location at Browns Mills on the edge of Pinelands region of central New Jersey. It is not known why that site was not chosen, but Crump eventually settled upon a site 15 miles south of Camden. And what a site it was-a sandy wasteland, covered in pine, oak and brush, punctuated by streams and small lakes.

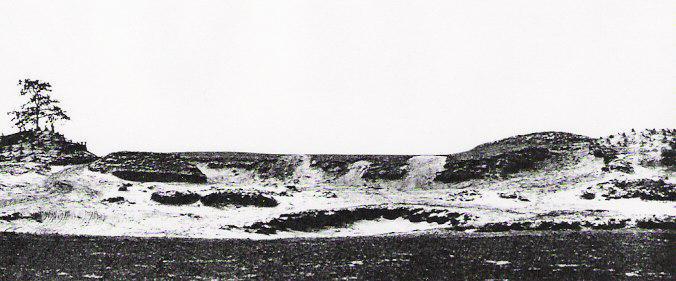

As Simon Carr observed, ‘It looks to have been some upheaval of the bed of the sea in bygone ages. There are ridges and rolls in every direction; big ones and little ones; long ones and short ones; hills and knolls, with every variety of shape and size. You could not fancy any contour of ground more admirably suited for golf purposes.’

October 8, 1911-Crump’s cousin and former business associate at the Colonnade, Henry J. Crump dies-he is only 59 years old.

There are a number of legends surrounding how Crump found the site. The two most common: Crump discovered the site gazing out the window of a train on his way to or from Atlantic City or Crump knew of the site from hunting trips, perhaps even as a boy. Another tale claimed he inherited the land from his father. An erroneous variation of the train story had British golf architect Colt on board with him.

The two most popular stories come from very reliable sources: the train window story comes from AW Tillinghast and John Arthur Brown, the hunting story from Jerome Travers and Alan Wilson. I suspect they are both true. He discovered the wild site from a train with perhaps an eye for shooting rather than golf, but once he began wandering the site gun in hand, he found the most perfect land for golf, land not unlike the rugged heathland outside London.

September 1912 Merion East is officially opened, construction began in the spring of 1911. North of the border-Colt’s Toronto is opened for play.

In September 1912 Crump informed his friends about his discovery. ‘I think I have landed on something pretty fine. It is 14 miles below Camden, at a stop called Sumner, on the Reading R.R. to Atlantic City-a sandy soil, with rolling ground, among the pines.’ A sandy oasis surrounded by rather uninteresting New Jersey farmland-for centuries the winter headquarters and hunting ground of the Leni Lenape tribe.

A number of friends ventured out for a look. Crump and Howard Perrin spent several days trampling over the ground-studying every inch. Satisfied, Crump purchased the 184 acres from the landowner, Sumner Ireland. After completing the transaction, he immediately took up residence at the site, pitching a tent near where the present clubhouse sits-spending his days studying the land, searching for potential golf holes, alone and on occasion with friends.

The raw beauty of Pine Valley-the sandy ridge at the second.

October 1912-Pennsylvania captures its first Lesley Cup at Huntingdon Valley.

Early the next year Crump began clearing the site to open up its full possibilities-no small task. At first dynamite was used, but it was largely ineffective due to the sandy soil. Eventually they brought in huge steam powered winches. At one point 22,000 trees had been uprooted before they grew tired of counting (some estimates place the number at 50,000). An army of men, horses and machines-one can envision the furious activity.

It is almost certain Walter Travis visited at this stage. Travis was in the area having played in an Atlantic City tournament-Howard Perrin was also in the field. He apparently traveled to Philadelphia after winning the event, we know he toured Merion with Perrin. An article appeared in The American Golfer (January 1913) under his pseudonym Far & Sure, in which he shared his impressions of Merion. It seems likely Perrin and Crump would have invited the Old Man over to inspect the property.

The Book of the Links is published-HS Colt contributes two chapters on golf design.

In American Cricketer January 1913, with permission from Crump, AW Tillinghast writes that a monumental project is underway. ‘If I had not been sworn to secrecy I would have told you about this some time ago. Now I am at liberty to do so. Work on a new course it to begin shortly. Although it is to be built on the sands of New Jersey, it will be close to Philadelphia as to make it very accessible…the course will be constructed to furnish an exacting test for the expert golf. It will be no place for the duffer or timid player. I have gone over the ground and I have never seen a more interesting stretch of golf country.’

Again in February Tillinghast announces the exciting new project, this time to a national audience in The American Golfer. ‘The new course is to be planned to meet the most exacting requirements of the modern game. It will not be for the novice or the timid player, and no effort will be made to include them in the two hundred which will limit the membership. The leading players of the section want this course to be a good, hard test of their games and worthy of a championship events…Nature has presented a rare opportunity to the golf architect and the men who will plan are all well-known players with every qualification that is necessary in work of this kind’

HS Colt sails for New York in late March 1913. He will visit New York, Boston, Montreal, Toronto, Hamilton, Chicago and Philadelphia.

By March the site had been surveyed and topographic map made. That same month Tillinghast writes another article in American Cricketer explaining ‘…Each of the eighteen holes will be designed by a prominent Philadelphia golfer, although the suggestions will, of necessity, be carefully considered by the committee, and in many details changes in order to insure variety and balance.’

The tee shot at the forth hole-note the relative openness.

The course is beginning to take form. Work has begun on the first seven holes-they should be ready for a spring seeding. The first was described as a two-shot hole bending to the right. The second was another par-4, the approach requiring a carry over an enormous bunker built into the side of a ridge. The third was a par-3 featuring ‘Alpinization’ a la Mid-Surrey. The fourth-another par-4 calling for two strong shots. The fifth was a short one-shot hole over a stream. The next hole was a par-5. And the seventh was less developed, it appeared to call for a drive over a ravine followed by a short approach.

The remaining holes have yet to be cleared, but Tillinghast gives the impression they have been identified. The home hole was a long par-4 requiring a second shot over water. The description of the first four holes and the eighteenth correspond with the same holes on the course today, the fifth was similar but shorter, and the sixth and seventh are quite different. In describing the over all feel of the course, Tillinghast wrote, ‘Nothing is lacking (even the variety of heather is growing about), anyone who has played over the British courses must at one remark the striking similarity of the surroundings.’

Sunnybrook and Seaview are first contemplated in April 1913.

In April a letter was sent out to prospective Pine Valley members:

For some years, a number of men who are interested in golf for golf’s sake have been thinking about the possibilities of a course easily accessible to Philadelphia, where the ground conditions were such as to allow the maximum amount of winter play. This place has been located by George A. Crump, some fifteen miles from Camden, on the line of Reading Railway, just below Clementon, N.J. It is sandy, rolling, wooded country, with streams of water flowing though it. Near enough to town to solve the caddy question and easily accessible, both by railroad and automobile. After satisfying himself that all of the various conditions of the soil, the general layout of the ground for a golf course and its accessibility were favorable, and acting upon advice of friends, he has purchased 184 acres for the purpose. So that the first important step toward a new golf course has been taken.

There are lots of attractive sites for bungalows. There’ll be room for forty or fifty of them and these will be sold to club members and the proceeds turned into the club treasury and we believe that this will go a long way toward paying for the main clubhouse.

It is not a land scheme, for the ground will be turned over to the club at very low cost price. It is not moneymaking scheme, for the various men interested up to date, proposed to give their time and money for its construction. It is just the beginning of a plan, whereby a first class golf course can be built, near enough to Philadelphia, so that precious time isn’t lost getting to it, and where, because of the character of the soil, we can get good golf during certain months of the year, when our courses are not playable.

A tentative plan for financing it is as follows: To pick out 200 to 250 good fellows, who are fond enough of the game and sufficiently interested in a plan to of this kind to buy one share of stock, at $100 per share. That will give us $20,000 as a starter. Then eighteen men have already been found, each of whom have agreed to plan and build one hole. In a rough way, it is estimated, that means $1000 per hole. This is $18,000 more. Then when things get going, an annual due will be charged of some small amount that will be enough to maintain the course. Those dues will probably begin January 1, 1914. An unpretentious, but comfortable clubhouse will be built, the real object being a fine golf course, rather than a fine clubhouse.

Now this is a very general and very rough sketch of the plans and we sincerely hope you are interested. There is room for a club of this kind; there is need for it and there are certainly enough men to whom this kind of a club will appeal, to make it not only possible, but an assured thing. Will you be one of them?

It is not an investment. If you buy a share of stock, you very probably will never get your money back, but it will be very well spent just the same.

Work on the construction of the course will begin this spring and it ought to be fairly ready by the fall of 1914. Fifty percent of your subscription is to be paid by July 1st, and the balance September 1st, and the sales of stock are not limited to one share. You must have one, but may have more than once, to become a member.

Fill out the enclosed blank and mail to

Committee on Organization

H.W. Perrin, Chairman

Jos. S. Clark

W.P. Smith’

141 men responded. It is interesting to note the original plan-as stated in this letter and in Tillinghast’s article-called for each hole to be designed by a different golfer, a unique idea to say the least. This most unusual method of design could present some potential challenges, particularly in the routing of the golf course, but it also illustrates the collaborative nature of the project as envisioned by the founders. Whatever the case, the group design idea would undergo some modification.

In May it was learned the British golf architect HS Colt would visit ‘to review critically the work already done.’ Colt was among an elite group of men who had elevated the state of golf design from a crude afternoon endeavor to an art and science. Among his credits were Rye, Swinley Forest, Stoke Poges, St. George’s Hill, Blackmoor, St. Cloud, Toronto, Detroit and the redesigned Sunningdale-many considered Colt the premier golf architect in the world.

H.S. Colt

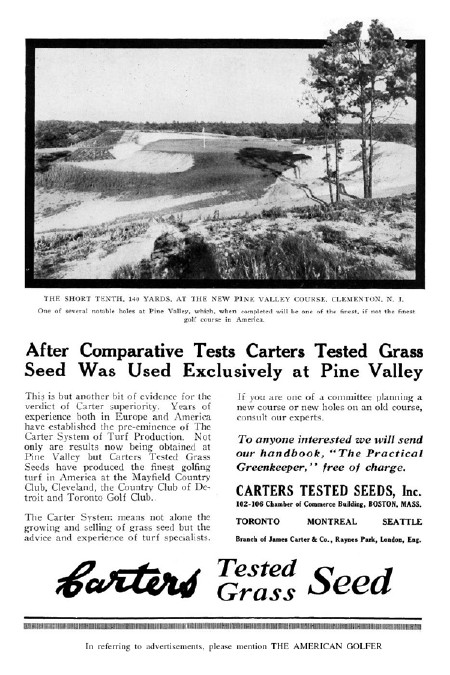

It is not known positively how Crump came upon Colt. It may have been while visiting Sunningdale in 1910, he was the club’s secretary. Colt was also associated with Carter’s Seed Company. Carter’s and Sutton’s were the two dominate grass merchants and construction supervisors in Britain. Carter’s had been involved in the construction of Swinley Forest, Sunningdale, CC of Detroit and Toronto. In fact it appears all the clubs on Colt’s North America itinerary were Carter’s customers-Garden City, Brookline, Chicago, Seaview, Merion, Sunnybrook and Pine Valley included. It is likely Carter’s was involved in arranging most of these visits, including the visit to Pine Valley.

In June Tillinghast reported Colt spent approximately a week at Pine Valley. The short article said Mr. Colt liked the land exceedingly and in his opinion it possessed greater possibilities than anything he had seen in America. ‘It is likely that some of his plans will be followed.’

Crump’s recollection of what occurred as told by Jerome Travers: ‘Crump’s vision began assuming concrete form when he engaged the famous English golf architect, Colt…deeply impressed with the scenic splendor, [Colt] pitched a tent in the woods and camped there for a week or more. He emerged from his hibernation enthralled. The same potential qualities for a wonderful links which Crump had visioned became even magnified under the critical analysis of the expert. He reported that it would be possible to mold one of the finest courses in the world….’Good! I thought so. I see it all as you do-the sand, the trees, the turf and rolling ground. Good! Let’s make it what you say-one of the best in the world.’ Crump was jubilant. Colt’s verdict was music to his ears; he told me of the happiness it brought him.’

Crump’s friend Joseph Baker some years later would claim Colt was paid $10,000 (£2,100) for his services. This figure appears to be on the high side. On the same 1913 tour Hamilton CC paid Colt $1533 for the design of its course. It is difficult to estimate what a job of the size and scope of Pine Valley would cost-Colt’s fee was normally 6% of the estimated cost of a project. And while finding the exact figure would be significant, one should not lose sight of the most important fact, Crump chose to hire an architect, a departure from the original idea.

Why the change? Perhaps Crump recognized his inexperience, even his most seasoned advisers-Tillinghast and Travis-were relative neophytes at that point in their careers. Considering the site’s extraordinary potential, hiring one of golf’s most skilled designers would appear to be a prudent decision-especially at such a critical stage.

When Colt arrives in late May, in addition to the few holes roughed out, there appears to have been a preliminary routing. This early routing, a simplistic stick and circle plan, was a mixed bag. Those familiar with the present course would recognize the first four holes, the sixth, seventh and the eighteenth-they are nearly identical. The remaining holes bear little resemblance to the course today. Who was responsible for this plan is a matter of conjecture-the likely candidate is Crump or Crump in conjunction with his ballsome-Perrin, Tillinghast, Carr, Smith, Travis et. al.

In recent years (1963 appears to be the first mention) it has been alleged Crump followed a set of strict design principles at Pine Valley. These principles include: each hole should be out of sight from every other hole, parallel holes should be avoided at all costs, and that the individual holes should box the compass, in other words no more than two consecutive holes should run the same direction-all very sound ideas.

The origin of these Crump principles is unknown. Adding to the mystery, the early stick routing deviates from these ideals. Regarding the supposed desire for each hole to be out of sight of the other, after Crump removed thousands of trees there was openness not isolation-exposed sand and a number of dramatic panoramas were a source of admiration. There was some limited tree planting early on, but it was designed to block the winter wind around tees and greens. Regarding the routing itself, there were a number of parallel holes in the initial Crump plan: 6 & 7, 13 & 14 and 15 & 16. In addition the 9th, 10th and 11th ran out in the same direction. Generally this early routing did not have the change of direction or the sophistication found in the latter plan, nor did it maximize the natural features as effectively.

An early view of the 18th-an impressive panorama including sandy tear in the adjoining hill.

One suspects the two men arrived at some of these principles together, quite possibly while Colt was reviewing this early routing-they were ideas most golf architects would have endorsed. All indications are that Crump was open-minded and willing to accept suggestions from others, and that the two men were in accord on most major philosophical issues, with one possible exception. Crump felt strongly a good shot should be rewarded and a poor shot punished, and punished severely. He envisioned Pine Valley as the supreme test for the strong with no concessions for the weak-survival of the fittest.

Colt on the other hand believed ‘the designer of a course should start off on work in a sympathetic frame of mind for the weak, and at the same time be as severe as he likes with the first class player.’ Colt’s plan, while well bunkered, provides options for the lesser man with fewer forced carries, overall less penal. However this was the one concept Crump would never compromise-Pine Valley would become a brutal test.

The first grass was sown in September and October-eleven holes were seeded. The turf progressed rapidly, and by November Crump, Perrin, Tillinghast and Richard Mott play the first round at Pine Valley. Just the first five holes are in play, but it is expected the entire course ‘will be ready at this time next year.’

In a December article in American Cricketer the new irrigation system is discussed for the first time-its prime function is to irrigate the greens. Jim Govan the pro/superintendent at St. David’s is hired. Govan, a Scotsman from St. Andrews, moves his family into a home on the property in early January. He would become Crump’s construction foreman.

Over the years, with the help of Govan, Crump would regularly hit experimental shots to help determine the placement of bunkers-Colt’s proposed bunkering arrangement would be revised. This goes back to their one philosophical difference. Crump intended to cruelly expose all weaknesses, he envisioned the ultimate test, and that is what Pine Valley became. And history has reaffirmed that decision. As CH Alison observed, Pine Valley’s framework was Colt’s, but the course’s spirit was Crump.

George Crump in search of a well-positioned hazard.

Crump and Govan also reworked and refined the greens. Who did what is difficult to say, but as a son of the Old Course, Govan must have felt at home on the course’s large undulating greens.

In January 1914 an extensive article on Pine Valley appears in the Philadelphia Inquirer. ‘The first blow of the ax was struck there last February; in the ten months since $40,000 has been spent by the holding company under the direction of George Crump, chairman of the Greens Committee, to whom more than any other man is due the credit for the wonders wrought…Without going into details it can be said no course in America has greater possibilities. Eventually not more than half a dozen links can be mentioned in the same breath. At present eleven of the holes are playable…but more holes have been cleared and it is certain that by next Thanksgiving the complete round will be possible, although it will take five years to whip it into full shape…after the course had been laid out, the advice of Colt, the English links architect, was secured. He made a few changes, mostly of a minor sort, one being the shifting of the 5th or pond hole from a mashie pitch to a full wooden shot.’

This article appears to minimize Colt’s involvement, his major contribution being the fifth hole. This limited role has been repeated often over the years. The article also mentions Crump’s bungalow on the edge of the pond near the fifth is finished and serving as the temporary clubhouse. He would live there during all seasons of the year. When Crump wasn’t supervising the work during the day, ‘he was seated next to the coal stove in his bungalow at night poring over his diagrams by the light of an oil lamp.’ Pine Valley was his whole life.

March 1914-land is purchased and Donald Ross engaged at Sunnybrook. It is likely Ross visits Pine Valley during this period.

In March Reginald Beale visits Pine Valley. Beale is one of the preeminent British turf and construction experts employed by Carter’s. Based upon his schedule, he appears to have been retracing Colt’s tracks. The club reported $45,000 had been spent to date and another $25,000 would be needed to complete the course. In an article in The American Golfer Tillinghast confesses that he had underestimated the quality of the course. He had only considered the merits of the first 12 holes constructed, but the last six holes, now being cleared and developed, are truly remarkable.

Merion West, designed by Hugh Wilson, is opened May 1914.

By May it is reported the course is coming along well. The few remaining holes to be cleared and will be ready for seeding in the fall. Again Tillinghast reiterates the remaining holes are better than he had hoped.

That winter while building one of the bunkers ‘a fine specimen of an ancient Indian stone hatchet was unearthed. It is nearly perfect.’ The discovery is followed by a small tremor.

WWI begins: Archduke Ferdinand is assassinated June 28, 1914. Germany declares war on Russia and France. Britain declares war on Germany-August 1914

Valley of Despair

If the plan was for Colt to return to New Jersey, that plan was now in serious jeopardy. In October 1914 HS Colt contributes to an article on Sunningdale in the British Golfer’s Magazine, ‘The only course in America that I have seen which resembles it [Sunningdale] in any way is the new course at Pine Valley, which I had the honor to lay out last year…’

As predicted the course is officially opened for the members in November, albeit a partially completed course. Eleven holes are in play and a new building housing the locker rooms is ready. Tillinghast writes glowingly of the course ‘discovered by Colt.’ He claims the final seven holes will be the best of all.

CB Macdonald visits and makes what will turn out to be a prophetic statement, ‘Here is the makings of one of greatest golf courses-if grass will grow.’

Simon Carr writes an extensive article published in Golf Illustrated January 1915 giving credit to both Crump and Colt for this magnificent course. ‘In order to procure the very best design for the golf course, Mr. Crump secured the services of that brilliant master of golf architecture, Mr. HS Colt, of international fame. Mr. Colt visited Pine Valley in May, 1913. After making a general inspection of the land, he declared his amazement that such a rare opportunity for a genuinely classical course should be found so near Philadelphia. He spent a full week examining the ground thoroughly, and then submitted plans of an eighteen-hole golf course, which, in his opinion, would be the equal of any inland course in the world.’

Simon Carr directing Ben Sayers around Pine Valley.

Carr continued, ‘The land on which the Pine Valley course is located is unique formation, confined to the locality…Mr.Colt was greatly impressed with it, and he has surely made the most of its opportunities in the superb plan which he designed, Nature made the golf holes. Mr. Colt discovered them.’

Carr explained that when Colt was hired he was informed of the quality and character Crump and the founders desired-including Crump’s no holds barred approach. He went on to describe the course’s many attributes: ‘…well-balanced variety of approach shots,..the whole 184 acres have been utilized; the course extends over all parts of the property…The plague of parallelism which afflicts many courses so sorely, has no place at Pine Valley. The fairways are wide and separated….Players at each hole are so well segregated that they enjoy only occasional glimpses of others…The wonderful topography of the place together with Mr. Colt’s skilful devising, has given individual character and appearance to each hole…The direction of the holes is constantly changing. Never more than two hole in succession follow the same direction. They are laid out to all points of the compass.’ The description of Colt’s ‘skilful devising’ sounds a lot like what eventually became Crump’s principles.

An excerpt from a 1912 essay on golf architecture explains Colt’s approach, ‘A couple of long holes at the commencement get the players away from the first tee…After that the sequence of the holes does not matter and what we have to look for are four or five good short holes, several good length two-shot holes, varying from an extra-long brassies for the second to as firm half-iron shot, one or two three-shot holes, two or three difficult drive and pitch holes, A fairly equal distribution between what I have designated as good-length two-shot holes and the others of all degrees seems to me to be about right. What we want to have is variety, gained by utilizing all the best natural features of the land, and alternating the holes of various lengths.’ Colt and Crump’s scheme at Pine Valley follows this outline to a T.

Seaview, designed by Hugh Wilson, officially opens January 1915. That same month, Crump, getting much needed R & R, sets the course record (75) at Pine Forest in Summerville, SC.

In March 1915 Tillinghast reports the original plans have been altered with Crump’s discovery of a great natural hole-the very strong par-4 13th. It had been found while clearing trees near the 12th green. This necessitates a change in the 14th and a slight change to the position of the 15th tee. The exact date of this discovery is not know, but it seems likely it occurred the previous year. In his January article, Simon Carr described the 13th as a longish par-4 (cleek approach) and the 14th as a drive and pitch. In Colt’s plan the 13th was a drive and pitch and the 14th a par-3. The change of the 14th from a par-3 to a par-4 alters the balance Colt had originally devised-leaving only three short holes (Crump would eventually convert the 14th back to a par-3). It is reported the final holes will be completed as rapidly as possible.

The nations foremost turf expert-Frederick W. Taylor-dies March 1915 from pneumonia.

In March the club also reports that clearing the ground, implements, seed, fertilizer, pipe, etc. has cost $101,135.63 to date. In April everything is coming along famously.

Sunnybrook, designed by Donald Ross, officially opens May 1915.

A Carter’s advertisement featuring a photograph of Pine Valley’s 10th hole appears in the July 1915 issue of The American Golfer.

In a July Crump receives a letter Walter Travis, he proposes an article on Crump’s desire to have Pine Valley played in reverse. ‘I have in mind illustrating some of them [various holes] in The American Golfer in connection with a brief account of what you propose doing in this direction…’

In the article (August 1915) Travis wrote, ‘Nature has been centuries in preparing this ideal tract for the hand of man in the ultimate creation of a real golf course, and man, in the person of George Crump, more particular, aided by other Philadelphia enthusiasts, has carved out a links which is just sure as anything to be one of the best-if not the very best-this country can justly be proud of. Laid out some two years ago by Mr. H.S. Colt, the eminent British authority on golf course architecture, sufficient progress has been made to justify anticipation of a most brilliant future…an unparalleled forward step has been taken by the projectors in arranging to make this the first course in the country capable of being played two ways-the regular way and in reverse order, making practically two distinct courses in one…with the capable assistance of Mr. Crump a comprehensive plan has finally evolved…’

It is difficult to say what might have inspired this scheme, perhaps St. Andrews, but whatever the case Crump’s idea had a major impact upon Travis. He would go on to design two reversible golf courses-Potomac Park (1916) and Westchester (1919).

September 1915: In a rare diversion Crump qualifies for the 1915 US Am at the CC of Detroit, a Colt design. In the first round Jerry Travers defeats him 15 and 14-a US Amateur record margin that still stands.

October 1915, an ambitious plan is announced for a golf course at Ocean City, NJ.

That autumn the project was jarred by a major setback-the golf course died, or at least the grass did. Tillinghast reports the course had shown a condition of considerable acidity blamed upon muck excavated locally and used in preparing the ground. The old greens will be brought back, and a similar error will not be repeated with the holes not yet constructed.

From the beginning establishing a healthy and dense cover of turf had been a problem, that was the primary reason for the delays. Initially the course was to be ready in the fall of 1914, but nearly three years after that prediction there were just eleven holes in play-and even then the turf conditions were not good. It is difficult to move ahead on the construction of new holes when you are unable to keep the existing holes alive.

When the course was originally prepared for seeding in the autumn of 1913, eight fairways were covered with manure (much of it imported from Holland on barges and transferred to the site by train car) mixed with the muck, which was then worked into the ground, and then seeded with sheep and red fescue. Alan Wilson recalled ‘The seed germinated quickly, grew beautifully and everything promised well, although the grass was somewhat sparse and lots of wash took place after every heavy rainfall.’

A great sandy expanse at the 6th

The fescue behaved as it normally does in sandy soil, it grew in tussocks, leaving bare areas in between. It was hoped with maturity the turf would spread out and fill in the gaps. Unfortunately when the rain came the bare areas had no roots to hold the soil, and cuppy hollows formed. ‘The fairways looked green; but of course the ball seldom stopped on a tussock, usually finding its way to the little hollows in between.’

In an attempt coerce the grass into these hollows, thus making a solid mat, Crump chose to enrich the soil with more manure. Wilson wrote, ‘The constant fertilizing helped the existing grass but did little for the bare patches; for as soon as a heavy rain came the manure washed away from them, and if we has no rain it dried up and blew away; and the same thing happened with to seed and topdressing, which were regularly applied twice a year. The net result was progress, but only a small increase of grass for the large effort spent’

The constant use of manure as top dressing was not only expensive-because much of it washed away-it also contributed to the unhealthy condition. Because the manure was lying near the top, Wilson explained, ‘it induced the roots to seek food near the surface, instead of forcing the roots to go deep, the only place of safety in sandy soil during our hot dry summers.’

And when hot dry weather came, which is what occurred in 1915, the grass grew brown, curled up and large areas died. This had to be a major blow to Crump, who had been struggling for three years to see his dream realized. Also contributing to the problem was an inadequate watering system, which effectively irrigated the greens, but not the fairways. Crump’s response was to re-fertilize, reseed and have the whole course given a winter covering of more manure.

In December Crump hired Robert Bender formerly of Sunnybrook who had worked under the late Frederick Taylor, the grass guru. His expertise will be utilized in restoring a number of lost greens and perhaps with some of the holes yet to be constructed.

January 1916, Merion is awarded the 1916 United States Amateur Championship only thirty-nine months after being opened, a remarkable accomplishment for a new course. Philadelphia had come a long way-in the fall the city would be hosting the best golfers from around the country. Although proud of the city’s accomplishment, it must have been a little bitter sweet for Crump and those at Pine Valley. At least the championship would give them an opportunity to show off their spectacular course-God willing.

Early in 1916, Samuel FB Morse hires two inexperienced California amateurs-Douglas Grant and Jack Neville-to design Pebble Beach. Morse was unable to persuade CB Macdonald and the top English architect [Colt or Fowler] was unavailable due to the war.

By February 1916 Pine Valley seems to be coming back, the putting greens are recovering rapidly after the period of anxiousness in the fall. The following month George Crump asserts the greens at Pine Valley have recovered fully from the setback the previous fall. Fourteen holes (including 11, 16 and 17) will be ready in the spring and in the fall all eighteen will likely be in sufficiently good condition. There are reports that Crump has spent over $200,000 of his own money to create the first fourteen holes.

The tee shot at the 16th

April 1916 Willie Park, Jr. moves to America to live permanently. Park had suffered financial difficulties necessitated this desperate move.

After three years of regular updates, there are no reports on the progress of Pine Valley for the remainder of 1916-a possible indication of continuing maintenance problems.

Construction begins in June at the new course at Ocean City, however world developments will ultimately delay its completion until 1923, by Willie Park, Jr.

September 1916: Merion hosts the United States Amateur Championship won by Chick Evans. WP Smith and Cameron Buxton qualify; Smith is knocked out in the second round, Buxton makes it to the third (quarter finals). Crump, Carr, Thompson, Perrin, and AH Smith fail to qualify. There is no mention of Pine Valley in the magazines, and one wonders if the condition of the course was a factor.

In February 1917 Howard Perrin is elected president of the USGA. Perrin must grapple with a number of important issues, not the least the controversy surrounding amateurism. His plate was quite full, having to oversee the state of American golf in addition to his business responsibilities.

In April the US declares war on Germany, entering WWI. A draft is introduced the following month for all men between the ages of twenty-one and thirty.

Pine Valley purchases the land surrounding the golf course in May 1917. The club property now consists of more than 500 acres. There is some indication a colony of homes may be in the plans-perhaps to relieve some of the financial pressure. At this time it was also reported there had been another setback with the turf-explaining the quiet period during the previous year. ‘The turf is improving rapidly and work is being pushed on holes 12, 13, 14 and 15. It is anticipated that these new holes will be ready for play in the fall and this will complete the entire course.‘

June 1917-after carefully considering the war condition, the executive committee of the USGA votes to abandon the amateur championship planned for Oakmont. Oakmont had recently been brought up to championship standard by William Fownes, another Lesley Cup regular.

The war has brought construction activities at Pine Valley to a halt. After a visit on the Forth of July Jim Barnes is extremely impressed with the four holes not yet constructed. He calls the 13th the best two-shot hole he has ever seen.

September 1917 Tillinghast writes that never before in the history of Philadelphia have so many promising young golfers come to the fore. ‘Her veteran players have, for the most part, retired from active competition. Generally they will be found at Pine Valley, very content to fight it out among themselves now, and often enough recall the struggles of other days. Never did any section produce a more wholesome coterie of ardent golfers.’

October 1917-founding PV member and Atlantic City regular, Robert Large dies at 42.

There was another long period of silence in the magazines and newspapers-everything is on hold due to the war. Establishing healthy turf continues to be an issue. Although radical, it appears the only way to correct the problem may be to plough up the entire course and start a new. A small fortune has been poured into the project and some are now referring to it as ‘Crump’s Folly’.

December 1917 Armistice is signed between Germany and Russia. As 1917 came to a close, the European Allies, their forces depleted, faced a German offensive designed to win the war before the American troops could arrive. At this time there is no sign of an end to this bloody conflict.

January 1918 George Crump is dead. Crump committed suicide on the mourning of the 24th at his home in Merchantville. The coroners report gave the cause of death as ‘Gun shot wound, Head, Suicide, Sudden.’ Others in the home at the time included his mother, his brother Ralph, who lived there as well, and a maid.

The following day, across the river in Philadelphia, the USGA was holding their annual meeting. Early in the proceedings Robert Lesley made a tribute to George Crump, and moved that an expression of sorrow be recorded in the minutes. ‘President Howard Perrin, who was a very close friend of Mr. Crump, was so grief-stricken that it was with extreme difficulty that he controlled his voice to put in the motion.’ Tillinghast wrote, ‘Never before has the writer seen strong men so genuinely moved by sorrow.’

The Philadelphia Evening Ledger ran long tribute to Crump on the 26th. It began:

‘The greatest monument to George A. Crump will not be the shaft that will be raised over his grave in the little Colestown Cemetery where he was laid away to rest today, but the Pine Valley Golf Club, of which he was the founder and builder.

His death was a tremendous shock to the thousands of his golf friends and few were aware that he was ill. It is to be doubted if there were ever a more popular man among his fellows than this quiet modest man, whom everyone loved.

Those who knew him intimately (and there were scores of these not only in Philadelphia but in all sections of the country) feel his loss more keenly and poignantly than they can express in words. There is a well-known phrase that expresses in a mild way just how they regarded him: ‘To know him was to love him.”

The tribute went on to describe his efforts at Pine Valley, ‘Years ago, with others, he conceived the idea of building a course which be used year round. And out of the underbrush, scrub oak and pine, growing on land that had never before been under cultivation, he visualized and built what promises to be the best golf course in this country.

If the title of Miracle Man can be applied to any golfer in this country it belongs to the master man of Pine Valley. No other man in the country would have attempted what he did four years ago.

And out of the underbrush and pine and oak there has grown a golf course which amateur and professional alike have said will be the finest test of golf in the this country if not the world. And even golf architects have gone on record in words of the warmest praise.

Into it he put $250,000 of his own money, and at no time did he ever worry whether he was ever going to get even a part of it back. It was to have been his life work, and the tragedy of it is that he did not live to see it completed.’

In the Philadelphia Record AW Tillinghast wrote:

The late George A. Crump.

Tillinghast again, this time in The American Golfer:

Tillinghast would later confess, ‘Never have I penned lines with more difficulty than those which announced the passing of George Crump, and the little tribute, weak in itself doubtless, never the less it came from the heart, for my old friend was a man who came hearts that way.’

Walter Travis wrote in The American Golfer:

‘In the sad death of Mr. George A. Crump his many friends-and their name is legion-sustained a great loss. And his loss to the golfing world is irreparable. For many years one of the leading golfers of the Philadelphia district his name will go down to prosperity as the founder of the Pine Valley Golf Club, a course which was ultimately destined, under his guidance and support, to become one of the most notable in the whole world of golf. Nearing completion just before his demise it offered every promise of becoming the classical course of the country, and had he lived to carry out all preconceived plans (which embraced the playing of the course the reverse way as an additional feature), there is little doubt he would have realized his fondest expectations. His whole life, of recent years, may be said to have been consecrated to this one idea, to the accomplishment of which everything else was secondary. No, not quite everything else, for with all his obsession of this one grand idea he never forgot his friends. Of a somewhat retiring disposition, he took delight in the playing of the game, and took greater delight in catering in every way to the pleasure of those engaged with him in his matches, friend and foe alike. No better sportsman ever lived.’

Two days after George Crump’s death Pine Valley’s Board of Directors met. These words were composed by his close friend Simon Carr and placed within the minutes:

Ellis Ames Ballard AH Smith

Cameron B. Buxton WP Smith

Simon Carr Wirt L. Thompson

Joseph S. Clark Herman Wendell

Howard W. Perrin J. Walter Zebley’

After months of silence and isolated frustration, Crump receives an outpouring of emotional support and admiration-unfortunately it was too late.

Almost ninety years after his death a number of unresolved questions persist. Why was the cause of his death misreported as complications related dental problems? Some have theorized the story was in fact true or at least partially true, that the severe pain associated with dental problems led to Crump’s suicide. While it is true illness is sometimes a cause for suicide, normally it is a terminal or debilitating disease, not a temporary malady, which is easily treatable.

The day before his death it was reported Crump had been out greeting acquaintances, not exactly consistent with a person in physical agony. However it is consistent with a person who has settled upon suicide, where there is tendency for the depression or anxiety to clear up right before the suicidal act, often the day prior the suicidal person may appear at peace or even optimistic-the calm after the storm and before the final act. As for the cause of his death, perhaps it was just easier for friends and family to attribute it to dental problems and not face the root cause.

Another probable reason for the false report was the stigma associated with suicide, particularly in those days. It may be more complicated than that however. There was certainly guilt and embarrassment involved, not necessarily guilt for Crump or his actions-but guilt among his friends for allowing him to get to that point. The entire burden for the project fell upon Crump. It became an obsession, and when events began turning against him the solitary burden was too great. Alan Wilson noted the irony, Crump worked and slaved to see his dream turned into a reality for his friends, ‘we who had advised so much and helped so little.’

The question remains, why did Crump take his life? We will never know for certain. There is no evidence he left a note, and even if he had, the underlying reasons would not necessarily be evident. What we do know is Crump was totally consumed with the project. He had no job or career. He had no wife or children. He had many friends, but he lived in isolation. His entire life was dedicated to one task-building Pine Valley.

And as we have documented, the project encountered numerous delays and setbacks. At the start it was hoped the course would be ready in a little over a year, but five years later only fourteen holes were finished and even those had serious maintenance issues. With world war raging and everything on hold, there were no prospects for the completion any time soon. To make matters worse, Crump had spent a fortune to get this point. If his money was not exhausted, it was nearly exhausted. (Several reports after his death indicated his money was gone) We will never know what was going through his mind that cold dark January mourning, but it had certainly been a tumultuous few years.

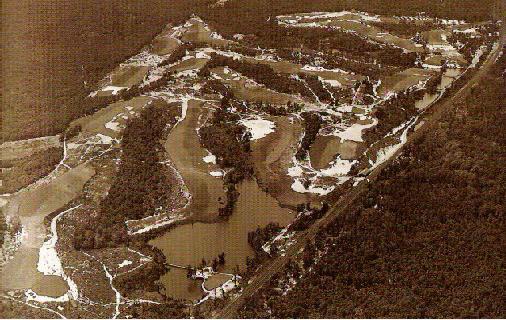

An aerial view of Pine Valley including the last holes to be completed-12, 13, 14 and 15.

With their guiding force gone, the club found itself in a tenuous position. Thankfully an unsung family member stepped in to insure the dream would not die. As Ellsworth Giles explained in The American Golfer, ‘Since Mr. Crump’s demise the task of carrying forward the work has fallen largely to a brother-in-law, who, without Crump’s passion and genius, is personally interesting himself in trying to carry out the founder’s wishes.’

Allan Wilson added, ‘He [Crump] had not only done all the work but he was the spirit and inspiration of Pine Valley, and his sudden death left the club in a peculiarly helpless condition, Fortunately his brother-in-law, Mr. Howard Street, took up the burden, and since has acted as secretary of the club and the chairman of the green committee.’

With Howard Street orchestrating; Grinnell Willis donated the funds to finish the last four holes; Alan Wilson solved the agronomic issues; his brother, celebrated amateur golf architect, Hugh Wilson oversaw the completion of the final holes; Simon Carr and William P. Smith, acting as Crump’s ultra ego, communicated the founders wishes; and Colt’s partner, CH Alison refined the final product.

By 1921 eighteen holes were in play, and the following year the golf course was in a perfected state thanks to Alison’s refinements. Four years after his death, and nearly a decade after the project began, George Crump’s dream was finally realized.

And so his story ends-a story of ironies. A man known for his generosity commits the ultimate selfish act. That tragic act is linked to turf difficulties, yet the foremost expert was briefly one of the club’s first directors. A man who retired early to enjoy life, dies young trying to fulfill his desire. A man who preferred to remain unknown is now lionized; his famous collaborator is an unnoticed figure. A man with so many friends lives in isolation. A golf course that was to be his dream becomes his nightmare.

We conclude with a poem written by AW Tillinghast days after George Crump’s death. It takes on added poignancy with a clearer understanding of his life and death. May he rest in peace.

IN THE PINES

Strangely quiet is the valley;

Through the clouds the new moon shines;

Now the whimp’ring wind of winter

Brings a murmur from the pines.

Listen to the moaning wind,

For the whispers sadly say;-

‘How desolate our valley

Since George has gone away.’

‘Men may raise a shaft of marble

And make words in chiseled lines,

But his true shrine, everlasting,

Shall be here among the pines;-

In the hearts of those who loved him,

Deep in hearts of men, who’ll say;-

‘How desolate our valley

Since George has gone away’.’

The End