Trees on the Golf Course:

A Common Sense Approach

by

Joe Sponcia

March 2016

Scotland and Ireland have their links, America has her trees. With course names that include, “oak, pine, willow, cedar, and hickory”, the American golf community has embraced the proliferation of trees on golf courses since the import of the game.

The mere mention of planting trees as part of a beautification campaign will assure you a seat on the board of directors or at the very least a sub-committee. But try and take a few out at your own risk, unless you want to be the club pariah.

Trees are beautiful, but they also come with a hefty and often unforeseen price tag. Are they the most expensive ‘feature’ on your golf course? It depends, but many greatly underestimate their impact on the yearly maintenance budget. Do the costs justify the end product? Many courses, especially those in the top 200 in America, have responded with a resounding NO.

“The irony, of course, is that Augusta National used to be the trendsetter in matters of course design. But now it’s well behind the curve. While Augusta is on a tree-planting splurge, most other prominent clubs are removing trees, having finally recognized their adverse effects on strategy, playability, and turf quality”. – Ron Whitten, Golf Digest, April 2006

Trees do serve a purpose, but like everything else in life, moderation is the key. When you strip away all of the emotion from the topic (which is often controversial) and look objectively at their impact on playability for all handicaps, current/ongoing/future costs as it relates to labor and course maintenance, and their adverse affect on pace of play, the argument to keep every single tree or add new ones becomes a hollow one.

Turf quality

“My basic point is that most people who (literally) embrace trees on golf courses are more interested in trees than golf. That goes for most of those arborists’ reports that look to protect trees and don’t bother to integrate trees with golf and turf grass”- Dr. Brad Klein

Grass needs three things to grow and remain healthy: adequate sunlight, water, and air circulation.

Ask your average club member about how to grow healthy turf and they might respond with: more fertilizer, more water, or a new Superintendent. If your course is prominently decorated with bare spots and stressed turf, more than likely trees are playing a major role in its demise, not your Superintendent. Shade is the biggest enemy of healthy turf. Grass is weakest (or non-existent) under branches, limbs, and where tree roots compete with the surrounding turf for moisture. Most turf grass varieties require at least 6-8 hours of direct sunlight. Without it, turf weakness and/or total failure is inevitable, especially when you consider the traffic on a busy golf course. Grass needs light to photosynthesize, producing food for growth and regeneration. When direct sunlight is too low for too long, carbohydrate reserves become depleted and plant cells become too frail to recover. Shade also prolongs the drying out period after heavy rainfall or irrigation, which is a leading cause of turf disease. The winter months are often the hardest on turf as trees block precious sunlight, which prolongs ice and delays frost thawing. Add a little traffic and expect heavy winterkill.

And what about water demand? Trees take a lot more than most people believe. A general rule of thumb is to measure the trunk at four feet above the ground and multiply by 10 (gallons) for every inch in diameter to determine water demand. Ideally, this quantity needs to be met once per week in the heart of summer. With clusters of trees, one can quickly see how turf often fights a losing battle just by doing a little math. Strong, healthy turf and trees are often at odds with one another, and in a head to head fight, trees always win despite the best efforts of experienced Superintendents.

“The final and easiest argument to make against trees on the golf course comes from an agronomic standpoint. Simply put, trees have no agronomic benefit to the turf grass on the golf course. They create shade, steal moisture, and out-compete turf grass for vital nutrients. – Jeff Harris, course developer, contractor, and operator based out of Maine

Holston Hills Country Club (Ross, 1927), 18th fairway, 2003. Thin, wispy turf was often the norm at the canopy edges.

Maintenance costs

“The problems trees cause for turf are well documented, and many articles have been written on the subject. Surprisingly little has been written about the costs of trees on golf courses. Many golfers assume that planting a tree is the extent of its cost, but nothing could be further from the truth. The cost of planting a tree is merely a small down payment on a bill that, for some courses, runs into hundreds of thousands of dollars annually”. – David Oatis, USGA

If you have ever shadowed your club’s maintenance staff for more than a day or two, it’s pretty easy to ascertain the areas that demand the most labor per square foot. While greens rightfully need the most attention (as do bunkers), the areas surrounding trees eat up time and labor at an inordinate rate when you consider the extra care needed to properly maintain their consistency.

A few line items to consider: How much labor does your club devote to string mowing vs. riding? Are there areas where riding would be more practical and not affect playability if trees were removed?

- Does your club maintain ‘special’ mowers that are only used around trees because of exposed roots? The cost to maintain and repair this equipment is often triple and quadruple the cost.

- How many times does your club re-sod the same areas year over year, and what is the annual cost?

- How much does your club spend on leaf, fruit, needle, and debris removal per year? Could this number be reduced?

- What is the annual cost for pruning and tree removal? When trees are properly placed (on the periphery), this line item can have minimal impact on the budget.

- How much does your club budget for adding additional trees?

- How often does your club tear out cart paths and repave due to root damage?

David Oatis of the USGA points out in his excellent piece, “The Hidden Cost of Trees”, that trees cost clubs an average of $88,000 per year and can run as high as $192,000. Many clubs greatly underestimate this cost.

Playability for all handicaps

It would be cost prohibitive and frankly over-reaching to suggest that every course in America resemble the Old Course in St. Andrews. Without heavy earth-moving equipment at the turn of the century, many of the Golden Age Architects laid out their masterpieces on rolling fields and open farm land. Years later, members took it upon themselves to add texture and beauty to the landscape by planting trees – which in many cases, completely changed the look and feel of the original layout. The problem was and still is today, a single plantings affects aren’t felt for some time with regard to playability (and agronomy).

Playability, in layman’s terms speaks to the fairness for all players, regardless of skill level, age, handicap, and/or gender. The biggest farce as it relates to trees on individual holes is the claim that trees, ‘even out the playing field’. Nothing could be further from the truth when you consider that low handicaps, who make up less than 3% of the average club’s membership, are adept at hitting fairway and green targets at a clip of 50% more than their mid to high handicap counterparts.

Trees on the corner of doglegs are a favorite of many club members for ‘protecting par’, but better players often go over, around, or past them, while the rest of the membership is blocked causing pace of play issues. The biggest fear is that any tree removal will render the course defenseless or ‘too easy’. Trees disproportionately hurt the least skilled. Ironically, high handicaps are often most in favor of keeping trees as a defense for par, but this is largely an ignorance and ego issue. Time after time, when massive tree removal is completed, handicaps remain virtually unchanged. The conundrum is two-fold: Club members love to brag about how tough their golf course is and trees hide poor play. If you’ve ever teed it up on a ‘wide open’ course and played poorly, your ego will say, ‘you stink’. Shoot the same score on a tree-lined course, and the same ego says, ‘it’s not you…the course is tough’.

In truth, greens have always been the equalizer and the greatest defense of par. Consider the make percentages for the PGA tour on the putting green (from www.pgatour.com) and then safely cut the average club members same percentages in half:

10 feet – 38%

15 feet – 22%

20 feet – 14%

25 feet – 10%

Next take a look at the average greens in regulation by handicap (via http://www.thegrint.com/range/2013/03/golf-tips-gir/)

25-30 – 10%

20-25 – 12%

15-20 – 20%

10-15 – 27%

5-10 – 36%

0-5 – 47%

Golf is hard.

“The purpose of a golf course is to have the game of golf played on it, and not to be viewed as an arboretum. The ground features and playing surfaces should always be top priority, with trees playing a supportive role”. – Jim Skorulski, Senior Agronomist, USGA

Like most things in life, tree placement isn’t a black and white issue, but many in the architectural community can agree on several common points. As a general rule, trees should reside on the periphery, meaning out of the way of a properly played shot, with few exceptions. Trees should complement individual holes, not adversely affect them, especially when it comes to the least skilled.

Included below are common pitfalls and their consequences:

- Avoid planting in the corner of every dog leg. Dog legs can be defined by bunkers and/or rough just as easily as they can by a cluster of trees. Both are a more fair option for mid to high handicaps because they eliminate distance and trajectory as the primary defense of par. The golden age architects used bunkers extensively on corners to create risk/reward options, a design principle that has only recently begun to take hold once again. The worst scenario is when a player is in the fairway, and his/her only option is a lay-up or punch out due to over-treed corners.

This is an all too common scenario on dog leg par 4’s where low handicaps and long hitters get a distinct advantage over their mid-high handicap counterparts. (Dog-leg left, green is in the foreground).

(Same hole as above, 40 yards forward) Take a look at all of the new plantings left of the cart path? How will the surrounding the turf look in a few years? How many times will the cart path need to be repaved in the future?

From the photo, this fairway appears sufficiently wide, but in reality is only twenty-three paces wide at 150 yards out on this par 4 that measures 373 yards. With a bunker left, water at the end of the fairway, and branches extending over the landing area, this hole induces lots of punch shots and lay-ups.

- Remove trees whose limbs hang over fairways, tee boxes, and especially those who impede sunlight around greens. The USGA recommends tree canopies be set back a minimum of 10 yards from the edge of fairways and tee boxes. Green sites, which are more fragile, need much more room, literally, to breathe. And what about yearly pruning? Pruning is better than the alternative, but as Dr. Brad Klein points out, “if a tree needs to be trimmed, it’s easier and better just to cut it down altogether. If it needs trimming, it doesn’t belong there”. Some would argue that this position is too extreme but the benefits outweigh the costs in almost every case: Wider effective fairway angles, better turf, more fair conditions for all handicaps, and increased safety as players aren’t forced into hitting shots from roots, buried or on the surface. Width is a point of contention for the robotic ‘too easy’ crowd, but the fact is, as handicaps rise, so does the challenge of hitting fairways that have narrowed over time due to tree encroachment.

Notice how the effective fairway has been severely compromised due to tree encroachment on what could be a fun risk/reward par 5. How can a slicer fairly play this shot after hitting the fairway?

“Make sure to select a planting location so that the mature canopy of the tree will not protrude on the line-of-flight between a tee and a fairway. Trees with protruding limbs dramatically reduce the usable size of a tee. For example, a tree planted too close to the front right hand side of a tee will promote concentrated use on the left-hand side of the tee. The result of such concentrated divoting on one side of the tee usually promotes discussion about the superintendent’s abilities. The solution to large overhanging limbs is usually sympathetic pruning that leaves the tree permanently disfigured. Actually, complete removal of a tree could be the best solution”. – American Society of Golf Architects

“Never plant large trees closer than 75 feet from a green or tee, because they will become serious competitors for available water and nutrients. Most individuals are under the mistaken impression that tree roots cannot extend outward from the trunk further than the drip line of the tree. In reality, tree roots can extend outward from the tree trunk approximately one to one and a half times the total height of the tree”. – American Society of Golf Course Architects

- Avoid planting in clusters. If one tree is good, four are better…or so it seems on many courses. The truth is, if you really like a certain tree and you really want it to have a strategic (not penal) impact on play, it is better to leave it on its own. Single plantings, while unfair in certain circumstances, do at least offer a chance for an exciting recovery. Clusters afford no such luxury more times than not. And is there any question aesthetically-speaking what is more preferable: A single specimen oak vs. a cluttered grouping?

“The key is to mix things up. Most courses cut from trees are repetitive, because the owners have tried to clear only the minimum amount, instead of trying to create a varied landscape. And most courses where trees are planted become repetitive, because if left unchecked, committees tend to plant in every available space, which leads to the same thing. As much as possible, one should avoid parallel holes separated by trees. If you’re stuck with that, sometimes make the clearing two holes across [or even three!] instead of one. Try to work on diagonals, or leave the trees tight along one side and very wide to the other side. Highlight the fine specimen trees [if there are any], use them as features, and remove all the clutter around them. Create longer views on the interior of the course; look for chances to open up behind the green” – Tom Doak

- Avoid creating ‘double-hazards’. The most common occurrence is pictured below where a tree is placed immediately in line with a bunker and the target. Situations like these are common where beautification committees ran unfettered many years ago. Not only do they unfairly hurt the higher handicaps, they greatly slow play hurting all players.

- Remove trees growing into cart paths. This should seem like the easiest point to get consensus on, but many clubs repave the same areas every few years. This is an actual excerpt from a blog post Steve Kealy, Course Superintendent, Glendale CC wrote: “Cart paths and adjacent trees are like oil and water, they don’t mix. When Glendale was built there were no trees on the course. The cart path routing was laid out and trees were planted. Maybe trees were planted to hide the paths, who knows? Fast forward fifty years and we have a lot of tree issues that need to be resolved.”

“This tree on the 5th hole is typical of so many trees on our course, it’s located right next to a cart path. The path is damaged from the tree roots and needs to be repaired. The only real fix is to dig up the path and remove the tree roots. This is an expensive process and we have paths all over the course in this condition. Golf carts and the people in them take a beating driving over these areas. Cutting off those large roots will buy us a couple years before the tree puts out more roots and the path is back in the same condition. The permanent solution is to remove the problem causing the path condition – cut down the tree! Does that tree really need to be there? That is the real question that needs to be determined.”

“This photo shows the path heading through the trees on the third hole where almost 300′ of path needs to be replaced. In the past we were able to add another 2″ overlay to smooth out the rough areas caused by the tree roots. As the trees continue to grow the roots get bigger and the overlay process is not an option any more. This path will need to be dug up and the asphalt hauled off to a recycle facility, the tree roots removed, a new layer of gravel added, and 4 ” of new asphalt installed. This is big money and a lot of time and disruption to do the work. The solution is to remove those trees causing the problem.”

5(a). Remove plantings on the inside of cart paths. Trees don’t hide cart paths, they hide players behind trees that others will hit into.

A no-brainer for tree removal with cedars shading just off the fairway, instead the area was re-sodded because they ‘make the hole’? Cedars are among the worst tree varieties for a golf course.

Seldom is there a need to plant trees on the inside of most cart paths. This is especially true around greens, where larger-sized tree species should not be planted within 75 feet of a green. Avoid planting larger-sized tree species altogether on the southeast side of greens, where they will block the morning sun. – Jim Skorulski, USGA

A few examples of proper framing:

Dormie Club, Pinehurst, NC. Notice how the player is invited to challenge the bunker on the corner, but in no way is dictated by over-hanging limbs.

Beautification Committees

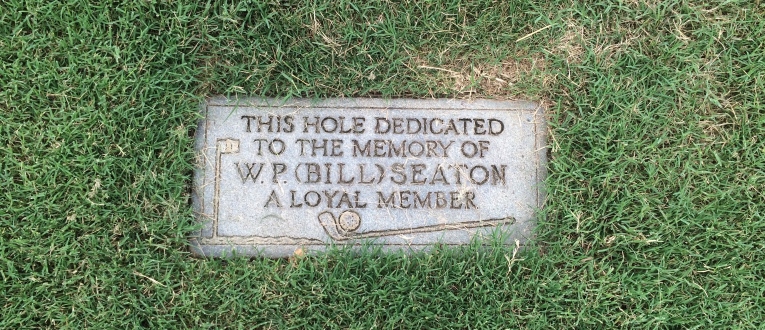

No group has collectively disfigured more golf courses across the United States than beautification committees. Well-meaning as they may be, the large majority are ill-trained and ill-equipped to pick suitable species or locations for trees. What looks like the perfect placement today will be a superintendent and players nightmare in 10-15 years as few grasp just how high and wide an individual tree often extends. This becomes even more dreadful when it comes to memorializing fellow members. In short, a memorial plaque in the clubhouse, a bench, or a marker on the grounds work much better, all things considered.

‘Great damage can be done to a golf course in the name of ornamental tree planting. Sometimes the argument is for safety between holes. Other times, the membership is determined to make or keep its golf course tough. But too often the plantings detract from the design. Among the worst offenders are those who specialize in course beautification. One of the most prominent of these, run by well-intentioned folks who neither golf nor understand golf strategy, consistently recommends an aggressive program that becomes tantamount to filling up every available space, even if it means with little dopey Christmas trees 10 yards off the fairway. Yet there is too much evidence of recent tree plantings, many of them alongside the landing areas of tee shots, or to block long hitters from carrying the inside of doglegs. Such tampering gradually puts at risk a wondrous piece of natural strategic contouring and subtly forces its artful ground game into a less subtle version of modern target golf’. – Dr. Brad Klein

Politics, master plans, and a few final thoughts

“The biggest challenge with trees that we have to deal with is, by far, golfer education. It’s an issue the USGA’s green section has been promoting in recent years. Golfers must understand that trees and turf do not get along and trees are not essential to a golf course”. – Adam Moeller, USGA

As mentioned at the outset, trees are by far the most controversial subject at any club.

Do they ruin the game of golf, as this essay may have alluded? In moderation, of course not! The problem is, there doesn’t seem to be enough moderation. If one says, “I don’t think this or that tree is fair and should be removed”, he is thought to want every tree removed?

Like an old western, the two gunslingers shout obscenities from the bar: the tree-hugger vs. the tree-hater. One armed with emotion, the other, logic. But who wins when both paint their opponent as the extremist straw-man?

Bobby Jones said, “I don’t see any need for a tree on a golf course”, but Augusta clearly had over 100 trees when it opened? With many golden age architects coming from and influenced by the links of Scotland, I would submit that their collective opinion would have suggested a limited place in the game. After all, could anyone fathom a Tillinghast or MacKenzie referencing how great their courses would become once the new green committees handiwork matured?

‘The extensive planting of trees to narrow the course may be the most extreme departure from Jones’ philosophy, particularly considering his wish that Augusta National would reflect links style golf’ – Geoff Shackleford

Width and angles (being on the correct side of the fairway) combined with thoughtfully crafted greens were the early architects calling card. The hemmed in fairways we see today at many clubs, where the only way to play a hole is down the middle has replaced fun with arduous and taxing.

Instead of tricking up individual holes with overhanging limbs, architects like Tom Doak are purposely creating wide fairways. Doak maintains that his, ‘favorite hazard is short grass’. But how could short grass defend par?

I’ll never forget meeting Rob Collins, of King-Collins design on a cold March day, as I marveled at the waves in the first fairway at Sweetens Cove. Collins said, ‘I like to imagine a fairway in the same way you would a bed sheet if you fluffed it once and then let it go’. How much more interesting is this than a fairway lined with cedars?

If you have gotten this far, you may be asking how you might help improve your own club? If you happen to be on your club’s board of directors or green committee, tread lightly when mentioning trees. It takes minutes to rev up fellow members, years to appeal to their common sense and quell their emotions.

In fact, the best advice, at least in the beginning is not to debate tree removal at all. The focus should be turf quality and health. To proceed otherwise will only get closed arms and clenched fists. Physically walking naysayers out to problems areas and asking bluntly “how can we grow grass (here) when we have this condition (a tree overhead)”, will prove itself more effective than years of meetings behind closed doors or debates in the 19th hole.

Generally speaking, few care or take the time to understand what width or options mean to their fellow members; the highest handicaps are an afterthought. Few attribute pace of play to misplaced trees which have undoubtedly pinched in multiple fairways. Few brag about having the easiest course in town. Things like wider fairways mean ‘pushover’ to the uneducated, but put these same golfers on vacation at one of Mike Strantz’ designs and they will marvel at how fun their round was after playing with a little width.

Few care about strategy either. Many would rather stump for a target-type course with few decisions, than one where a player can run up a three wood onto a par five, even though the missed par five could actually get the player in more trouble than a forced lob wedge. They only care about difficulty and being perceived as a ‘test’ (“They, many, and few” refer to the average club member).

If your club is of a certain pedigree; designed pre-1950, by a Ross, Raynor, or Tillinghast, the task of restoration and/or clean-up will be much easier than if it was designed by a lessor name. A good starting place is to find the original drawings or course master plan…and then circulate it throughout the club. If none can be found, original pictures can prove to an invaluable part of any improvement plan. Many will be stunned when they see how much the course has changed (probably for the worse).

As it relates to lost fairway width, Google Maps has proven to be an excellent resource for measuring changes over a time.

Above all, enlist the help of an expert. The USGA has regional arborists that can do a site survey and provide a thorough report that will touch on many aspects mentioned in this essay. The American Society of Golf Architects is another great resource to turn to if and when an objective expert is needed. Undoubtedly, the greatest objections to many of the points discussed will come from the least educated among us.

Selected quotes:

Willie Park, Jr.:

“Trees are never a fair hazard if at all near the line of play, as a well hit shot may be completely spoiled by catching the branches.”

Charles Blair Macdonald:

‘Trees in the course are a serious defect, and even when in close proximity prove a detriment.’

“No course is ideal which is laid out through trees. Trees foreshorten the perspective and the wind has not full play. To get the full exaltation when playing the game of golf, one should, when passing from green to green as he gazes over the horizon, have a limitable sense of eternity, suggesting contemplation and imagination.”

Harry S. Colt:

‘There is of necessity a feeling of restriction when playing the game with 6-foot oaks paling on every side…The sense of freedom is usually one of the great charms of the game, and it is almost impossible to lay out a big, bold course in a park unless it be of large dimensions, and one needs some three or four hundred acres within the ring of fence to prevent the cramped feeling…It is essential to make the clearing bold and wide, as it is not very enjoyable to play down long alleys with trees on either side.’

‘Trees are a fluky and obnoxious form of a hazard.’

‘In cases where the ground is covered densely with trees, it is often possible to open up beautiful views by cutting down additional timber. In such cases, it would be unwise merely to clear certain narrow lanes, which are required for play. The landscape effect should also be studied, and although great care must be taken not to expose any unpleasant view in the process, every endeavor should be made to obtain a free and open effect.’

‘On the other hand, where very few trees exist, every effort should be made to retain them, and in every case the architect will note the quality of the timber with a view of retaining the finest specimens.’

Max Behr:

‘It goes without saying that trees lined to hem in fairways are not only an insult to golf architecture, but the death warrant to the high art of natural landscape gardening, aside for the fact that, of all hazards, they are the most unfair.’

Stanley Thompson:

‘In clearing fairways, it is good to have an eye to the beautiful. Often it is possible, by clearing away undesirable and unnecessary trees on the margin of fairways, to open up the view of some attractive picture and frame it with foliage.’

George Thomas:

‘Trees and shrubbery beautify the course, and natural growth should never be cut down if it is possible to save it; but he who insists in preserving a tree where it spoils a shot should have nothing to say about golf course construction.’

Donald Ross:

‘As beautiful as trees are and as fond as you and I are of them, we still must not lose sight of the fact that there is a limited place for them in golf. We must not allow our sentiments to crowd out the real intent of a golf course – that of providing fair playing conditions. If it in any way interferes with a properly played stroke, I think the tree is an unfair hazard and should not be allowed to stand.’

Alister Mackenzie:

‘Playing down a fairway bordered by straight lines of trees is not only inartistic but make tedious and uninteresting golf. Many green committees ruin one’s handiwork by planting trees like rows of soldiers along the borders of fairways.’

‘Narrow fairways bordered by long grass make bad golfers. They do so by destroying the harmony and continuity of the game, and in causing a stilted and cramped style by destroying all freedom to play. There is no defined line between the fairways in the great schools of golf like St. Andrews or Hoylake. It is a common error to cut the rough in straight lines. It should be in irregular, natural-looking curves. The fairways should gradually widen out where a long drive goes; in this way a long driver is given a little more latitude in pulling and slicing.’

‘The difficulties that make a hole really interesting are usually those in which a great advantage can be gained in successfully accomplishing heroic carries over hazards of an impressive appearance, or in taking great risks in placing a shot so as to gain a big advantage for the next. Successfully carrying or skirting a bunker of an alarming or impressive appearance is always a source of satisfaction to the golfer, and yet it is hazards of this description which so often give rise to criticism by the unsuccessful player.’

‘In an ideal hole, there should not only be a big advantage from successfully negotiating a long carry for the tee shot, but the longer the drive, the greater the advantage should be. An ideal hole should provide an infinite variety of shots according to varying positions of the tee, the situation of the flag, the direction and strength of the wind.’

‘We can, I think, eliminate difficulties consisting of long grass, narrow fairways, and small greens, because of the annoyance and irritation caused by searching for lost balls, the disturbance of the harmony and continuity of the game, the consequent loss of freedom of swing, and the producing of bad players.’

Bruce Hepner:

‘Many golfers believe that widening a course will make it easier. This may be true for high handicappers, but wide angles can make the course more difficult for better players. Less skilled players are afforded room to enjoy their round and better golfers are provided strategic options that induce thought and, in turn, make for a more sporting game. The weak players may shoot 98 instead of 103. There’s nothing wrong with that.’

Geoff Shackelford, reiterates that classic architects built holes:

‘… where there was no right way or clear way to play them’. If there was a ‘right way’, certainly there was never an agreement of opinion. Many restorationists claim that there are two necessary ingredients to recapture original designs, undulating green complexes and extreme fairway widths, the latter of which is most essential. Wide fairways create ‘mystery, variety, strategy, options, and choices and further encourage thought, decision-making, shoemaking, and recovery play’. These elements have all but diminished today with much narrower fairway widths. Tee shots are forced to the center, and any lateral alternatives are too penal for its reward. The only right way to play the hole is straight. How uninteresting and monotonous.’

Jack Nicklaus:

“Pinehurst #2 is the best course I know of from a tree-usage standpoint. It’s a totally tree-lined golf course without one tree in the playing strategy of that golf course. I love what Donald Ross used to do at Pinehurst. Every year Ross would walk through the trees and say, ‘that tree has gotten too big; you can’t play a recovery shot from there any more. Take that tree out and that tree out and cut the branches of that one’. Then if you hit it in there, you could get in and play a recovery shot back out. Too many trees prevent recovery shots, and I think the recovery shot is a wonderful part of the game.”

Ron Forse:

‘Permanent ground features dictate design, not trees, (unless an old oak, or such, can be used). Many courses are now going to the expense to remove trees, and the lesson is use them sparingly. Safety is an important use for trees, and improperly placed trees destroy design intent.’

‘A good golf course is one that tests the golfer’s wit as well as his ball-striking ability. Strategy requires a golfer to put varying values on his successive shots on a golf hole. If a golfer risks a hazard on the tee shot he should be rewarded with an easier approach shot to the green. Strategy implies alternative routes from the tee to the green. This mean that the golf hole should be sufficiently wide to give players choices of direction. The golfer may choose to hit around trouble but has a proportionally lesser chance at par if he does so. The bunkering and other hazards thus come into play for the bogey golfer as well as the scratch golfer. The beauty of the strategic design is that the bogey golfer can enjoy his round as much as the scratch golfer. Also, these strategic courses are forever enjoyable for every golfers ability.’

Reed Mackenzie, USGA President (2002 Golf Digest/October):

‘I hate them. Why? Three reasons, really: the agronomics (Trees end up costing you a lot of money; you get areas where you can’t grow grass), the emotions they stir, (People become attached to trees, and their attachment is irrational) and the practical realities (Trees get diseased and fall down).’

Dr. Brad Klein:

‘Trees should play no more than a framing role on a golf hole. On linkslands they play none, on parkland they usually play more, but I think it is overdone. For the most part, trees are hopelessly overused to create – or destroy – strategy and to block out the ground features. The occasional overhanging hardwood on the inside of a dogleg is tolerable once a round, but never more, and only if there is room around it to play. Trees with memorial tree-planting programs are hopeless. Clubs that trim their trees back are flailing at the wind. Wholesale removal is the only way to go.’

‘Nothing is more frustrating for the advocate of a restoration project than having to face dozens of fellow home club golfers who think no changes are needed. “Don’t fix it unless it’s broke,” he’ll be told. “We love our course just the way it is.” “It’s always been like that, don’t mess with it.” “The trees are the best part of our course. Each of these oft-uttered clichés is evidence of ignorance.’

‘Tree management is crucial to good turf quality. That usually means tree removal. Without getting into the details of arbor care, suffice it to say that any restoration effort has to focus on tree management, and the best way to defend this objective (knowing how much people love their trees) is to make a case for the healthy turfgrass that will be produced.’

Tom Doak (excerpted from ‘Anatomy of a Golf Course’):

- Avoid planting trees to the inside corner of a dogleg hole or even near typical landing areas. These positions undermine the principles of strategy and shot making.

- Avoid planting trees too close to the playing areas, especially tees and greens, because of turf-grass issues.

- If necessary, plant trees between typical hitting areas and typical landing areas, so long as they do not affect playability.

- Avoid filling up every open space with new trees.

- Avoid planting new trees too close to sand bunkers or other hazards. Such would create a double hazard for the golfer to avoid.

‘The same club members who tell me that taking down a tree or expanding a green will make the course “too easy” will turn right around the next minute and tell me that restoring a cross bunker would make the course “too difficult’.

David Oatis (USGA Agronomist): ‘Trees are an integral part of many courses and can perform a variety of valuable functions. Trees can add definition and strategy, improve safety, and add a wonderful naturalizing quality to the landscape. However, trees can also wreak havoc on golf courses. Between the shade and reduced air circulation caused by their canopies, and the competition caused by their root systems, trees can make it physically impossible to grow healthy turfgrass. They can cause severe play- ability problems. USGA Green Section agronomists have for years agreed: Trees are the leading cause of turf- grass failure and poor performance in North America’.

Special thanks to Jon Cavalier and Robin Hiseman for their photo contributions.

Bibliography:

Proper tree watering 101, http://treegator.com/watering/index.html

In praise of width, Tyler Kearns, http://adventuresingca.blogspot.com/2012/11/in-praise-of-width.html

The Hidden Cost of Trees, David Oatis,

http://gsrpdf.lib.msu.edu/ticpdf.py?file=/2010s/2010/100504.pdf

Man’s friend or Enemy, David Oatis,

http://gsrpdf.lib.msu.edu/ticpdf.py?file=/2000s/2000/000701.pdf

Using technology to solve and old problem: Trees, David Oatis,

http://gsrpdf.lib.msu.edu/ticpdf.py?file=/1990s/1997/970520.pdf

A guide for selecting and planting golf course trees, Jim Skorulski,

http://gsrpdf.lib.msu.edu/ticpdf.py?file=/2000s/2009/091101.pdf

The pitch for preservation, Dunlop White III, http://www.donaldross.org/Default.aspx?pageId=147090

Trees – The biggest problem of golf course turf, James Snow, http://archive.lib.msu.edu/tic/mitgc/article/199385.pdf

Below the Trees, Dunlop White III, https://golfclubatlas.com/in-my-opinion/below-the-trees-by-dunlop-white-iii/

The cutting edge, Dunlop White III, http://www.dunlopwhite.com/www.dunlopwhite.com/Restoration_and_Tree_Management_files/LINKS_Oakmont.pdf

Wide Open – A new angle on Width, Tom Ferrell, Mark Fine,

http://www.finegolfdesign.com/articles/golf_tips_7_05.pdf

The role of the Green Chairmen, Dr. Paul Rowe,

http://gsr.lib.msu.edu/2000s/2009/090708.pdf

The End