The Evolution of a Classical Golf Course: Essex G&CC

by Jeff Mingay

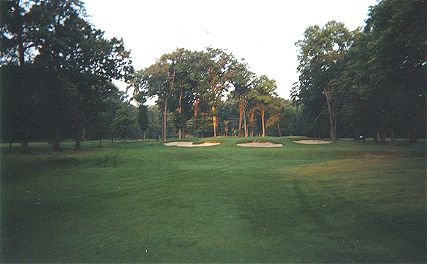

The beautiful fairway Ross bunkering on the second is obscured by encroaching trees.

By the 1960s, the majority of classic golf courses designed and constructed during The Golden Age of Golf Design, between the wars, were suffering the effects of evolution. Putting surfaces had receded toward their centers, fairways had narrowed, sand bunkers were deteriorated or had been filled in, and trees had grown to infringe on former lines of play and threaten the health of the turf grass.

Windsor’s Essex Golf & Country Club, designed by Donald Ross and opened for play in 1929, was no exception. In fact, the story of Essex’s evolution over seventy years mirrors that of hundreds of Golden Age layouts throughout North America.

The following chapter, titled The Evolution of the Golf Course, from the forthcoming book, One Hundreds Years of Golf, A History of Essex Golf & Country Club: 1902-2002 by Jeff Mingay chronicles Essex’s evolution, and offers valuable insight to other clubs whose Golden Age layouts have suffered a similar fate.

Golf courses are in an unremitting state of evolution. They are inevitably subject to constant change.

‘A golf course can never stand pat, because it is by nature a growing thing,’ wrote golf architect Bruce Hepner in a 1999 club commissioned report tracing the history and design theory behind Essex.

Based in Traverse City, Michigan, Hepner is vice-president of Renaissance Golf Design, Inc., the acknowledged industry leader in consulting clubs with classic golf courses. In 2000, a master plan to restore Donald Ross’s original design devised by Hepner was approved in concept by Essex directors.

As golf courses age, trees grow to infringe on former lines of play and cause agronomic problems, fairways tend to become extremely narrow relative to their original widths, and putting surfaces shrink, receding toward their centres. Essex’s greens have lost a significant amount of surface area since 1929.

‘Rather than scalping taller grass at the edges,’ wrote Hepner. ‘maintenance workers tend to take the mower ever so slightly inside the outer edge of the green as they do their daily work.’

As a result, an average putting green can be expected to lose about one-eighth of an inch of surface area per year, according to Hepner. Multiply one-eight of an inch by 72 years and the dramatic nature of this phenomenon presents itself clearly.

The one shot fifth - the green originally extended further right.

‘Also, as equipment changed from walking mowers to riding triplex mowers,’ Hepner added, ‘the perimeters of putting greens tended to become rounded off into broader curves because of the wider turning radius of the riding machines.’

At Essex, Ross built artificial plateaus on which to set the putting greens. ‘(Originally) the green surfaces extended right out to the top edge of the grassy banks that surrounded them,’ explained Hepner. ‘The shape of the green was not rounded, but instead had several distinctly straight sides with very quick turns between them.’

One of Ross's best greens anywhere - the sixteenth at Essex.

Several of Essex’s greens, such as the fourteenth, were originally rectangular in shape with elongated corners. Others featured distinct lobes of putting surface jutting behind and between greenside hazards. Over the years, the extended corners have been rounded off, the lobes have been lost. Essex’s greens have taken more of an circular or oval shape.

‘Returning all of the greens to their original size and shape would give (Essex) a distinctly old-world look that is increasingly rare and valuable today,’ Hepner suggests.

Expanding the greens to their original parameters would also re-introduce Essex’s most challenging hole locations on the outer edges of the greens that force golfers to play strategic angles.

Ross employed wide fairways at Essex to provide for various angles of attack. According to Hepner, Ross intended to put the premium on the second shot and allow a freer swing from the tee. In fact, this scheme is very typical of Ross’s style of design, exemplified by his two most famous layouts at Pinehurst, North Carolina and Seminole Golf Club on the Atlantic coast of Florida.

Ross used bunkers sparingly at Essex. Instead of directing golfers to a safe landing area off the tee, he wanted them to figure out for themselves where to drive in order to approach the day’s hole location from a favourable angle. ‘But over the years, with the growth of trees, shrinking fairways and greens, and the addition of new fairway bunkers, Essex has evolved into a Ëœdriving’ course,’ says Hepner.

Whereas Essex’s fairways were uniformly 50-60 yards wide when the course opened, they average a mere 26.4 yards across today. For the sake of comparison, the United States Golf Association narrows fairways to between 27 and 30 yards across for their Open championship, which is considered to be major championship golf’s premier driving test.

According to Hepner, 30 to 40 yard fairway widths are considered the norm for member play these days.

Restoring strategic hole locations necessitates adjustments to fairway patterns in order to provide more latitude for better golfers to play down the edges of the fairway if they wished to obtain the best angle of attack to a tight pin placement. ‘But to make the fairways much wider (than 30-40 yards) would open the course to criticism from good players that it is Ëœtoo easy’ or that Ëœits shot values are too lenient’, even though we would actually be restoring exactly what the designer built in the first place,’ wrote Hepner.

‘Also, because of the much higher standard of grass we expect on modern fairways, there would be significant budgetary ramifications in returning the fairways to their original width. It would probably increase the area of highly maintained grass by 50 per cent.’

For these reasons, Hepner does not propose windening all of the fairways back to their original widths in his master plan. But he does recommend some additional width and shifting of the fairways, here and there, to restore strategic angles of play and driving options. And also to bring fairway bunkers currently ‘out in the roughs’ back into play.

It was less than half a year after the Matchette Road course opened for play that the stock market collapsed in October 1929. For more than 15 years after “ throughout the Great Depression and the Second World War “ the club shouldered a heavy financial burden and, in turn, greenkeeper John Gray struggled with a nearly non-existent course maintenance budget.

Gray single-handedly saved the golf course from extinction on several occasions throughout these difficult times. Club records indicate that he frequently purchased necessary maintenance supplies and equipment with his own money, without a guarantee of reimbursement from Essex directors. Still, with a limited budget and an inadequate labour force, Gray’s outstanding abilities were limited. Under the circumstances, it is quite possible that some fairways and greens had already lost their original size and shape by the mid-1930s.

Following Gray’s sudden death in 1958, the condition of the golf course was in an apparent state of decline. The club went without a full-time greenkeeper for the entire 1959 season, charging club secretary W.A. Dawson to take on greenkeeping duties with some assistance from William Gravett, who then head of the city of Windsor’s Parks Department. Gravett visited the club infrequently during the 1959 golfing season in an advisory capacity.

Gravett was hired as the club’s full-time greenkeeper beginning January 1, 1960. Although he was familiar with growing grass and looking after trees and flowers, Gravett had no previous experience in golf course maintenance and the results of his sincere efforts were less than satisfactory.

In 1964, Essex directors engaged golf architect and agronomist W. Bruce Matthews of Newaygo, Michigan to examine the course and suggest potential improvements. In a written report submitted to the club in September that year, Matthews provided advice on mowing and irrigation techniques, fertilizer applications, drainage improvements, and tee reconstruction. Several tees on the course featured undulating surfaces at the time and others, particularly at the par 3 holes, were too small to accommodate a dramatic increase in play that began in the early 1960s.

Prior to 1961, when the course’s first automatic watering system was installed, greens, tees and fairway landing areas were hand watered with portable hoses. While the pond fronting the 8th green and 9th tees provided an adequate water supply for selective irrigation, it proved to be unable to adequately supply the new comprehensive watering system. In fact, it was not uncommon for the pond dry up in times of drought.

During the mid-1950s, in anticipation of installing a more elaborate irrigation system, Gray hatched an ambitious plan to pump water to the golf course from the Detroit River, some four kilometres away. However, his idea was found to be impractical and too expensive. Other attempts to find well water on the property had also failed. Only sulphur water was discovered.

For the record, a sulphur water well behind the 2nd green was used to refresh the horses during the construction of the course. It was covered over shortly after the course was completed.

As a means to increase irrigation water storage capacity, Matthews extended the pond further in front of the 8th green and deepened it. He also suggested that reducing the fairways to 130 feet across would result in more efficient use of the more efficient use of the available water. As a first step, Matthews recommended gradually reducing the fairways to 145-150 across, which clearly illustrates the extreme width of the fairways at the time. One hundred and fifty feet equals 50 yards.

Essex’s fairways were narrowed further, to approximately their present-day widths, by Royal Canadian Golf Association officials in preparation for the 1976 Canadian Open. Many of the narrowest fairways today “ namely the fourth and the eleventh “ have not yet been returned to their former width.

Matthews also suggested that several fairway bunkers in the 100-170 yard range off the tee should be eliminated, citing that advancements in playing equipment technology had rendered them useless. While it is unclear which, if any, such hazards were removed on Matthews’s advice, it is known that a number of short bunkers were filled in during the early 1960s at the request of a group of lady golfers who felt they were unfairly penalized by them. Prior to 1960s, very few women played golf regularly at Essex.

Today, there is only one original driving are bunker left on the course: some 170 yards off the 3rd tee on the left. The bunkers and mounds complex along the right side of the 2nd fairway is approximately in its original location, but those bunkers were reshaped and reconfigured during the early 1970s by golf architect Arthur Hills.

Based in Toledo, Ohio, Hills was hired by Essex directors in 1967 to devise a master plan for golf course improvements. He immediately improved drainage throughout the course and also removed Ross’s remaining short bunkers, which Hills labelled ‘vestiges of the past.’

Hills added several new bunkers to the course throughout a 32-year association with Essex. These bunkers include those between 230 and 240 yards off the tee at the first (added in 1980, third (1996), ninth (1996), tenth (1980), thirteenth (1996), fourteenth (1996), fifteenth (mid-1970s), sixteenth (1979), and eighteenth (early 1980s) holes.

Hills also reshaped many original bunkers throughout the years, such as one fronting the left side of the 8th green that was refashioned with a distinct cape of turf jutting into the sand. Ross’s original bunkers were generally much simpler in shape, with sand flashed high on the interior face, bordered a ‘turf ribbon.’

The bunkers fronting the 7th green, as they appear today, are perhaps the best examples of the original bunker style at Essex.

In 1969, Hills installed the pond separating the 11th and 13th holes principally as a means to increase irrigation water storage capacity. Previously, there was a drainage swale that meandered between those two holes. Along with the planting of many new trees, the installation of the pond dramatically altered the complexion of the incoming nine holes, particularly numbers eleven and thirteen.

Hills instigated an ambitious tree planting program during the early 1970s partially in response to Dutch Elm disease, which ravaged golf courses throughout North America during the 1950s and ˜60s. Although there is no accurate record available, Essex is said to have lost several hundred elm trees to the disease.

With the fairways having narrowed, many of the new tree additions were planted inside the original tree lines established by Ross. According to his biogrpaher, Bradley S. Klein, Ross’s clearing plan always called for corridors at least 40 yards wide on short holes, with fairway and adjoining rough ground 60-90 yards wide on longer holes. Today, several corridors of play at Essex, including the eighth, are far narrower than Ross would advise.

Whereas nearly all eighteen holes at Essex are lined with trees today, the course previously featured impressive solitary elms and oaks and sporadic groves with open spaces between them that provided attractive vistas across property. These spaces have been filled. And many the newest trees are causing agronomic difficulties today.

‘Bunkers and greens surrounded by trees have become a maintenance problem,’ Hepner wrote in his November 1999 report. ‘Non-indigenous species of ornamental trees and shrubs clutter the open spaces meant for golf views and play. Turf grass has suffered due to a lack of sunlight and air circulation.’

The tightly bunkered 7th.

With assistance from Hepner and United States Golf Association agronomist Robert Vavrek, golf course superintendent Chris Andrejicka has selectively cleared, pruned and relocated a number of trees in recent years with outstanding results. Andrejicka has also planted many trees throughout the course in consultation with Hepner and Vavreck, who assistance to ensure that new additions will not cause future problems.

‘The goal is to have a healthy forest with the proper specimen golf trees enhancing the game,’ wrote Hepner. ‘In golf, trees enhance the game, not impede.’

In his master plan for course improvements, Hepner also recommended that the original fairway bunkering schemes devised by Ross be re-introduced to golf at Essex. Ross had a penchant for staggering bunkers at varying distances from the tee so that all golfers, regardless of ability, had to take account of at least a few on occasion. Ross’s style of bunker placement mimicked the randomness found in nature.

‘Yes, the low-handicappers do sometimes fly their drives past the bunkers Ross intended for them,’ explained Hepner. ‘But the average member probably now hits his ball far enough for these bunkers to come into play, and thus derives the interest from the course that it held for the better players in the 1920s and Ëœ30s.’

Like Ross, Hepner also believes that bunkers should be found at varying distances from the tee.

‘If we tried to move all the bunkers to a Ëœmagic distance’ to threaten the low handicapper’s drive,’ he added, ‘we would succeed only in requiring additional renovation to the course in another ten or twenty years when players have learned to hit the ball 15 yards further. I don’t think that the goal of any bunker renovation project should be to make the course tougher for the few and less interesting for the majority.’

Implementation of Hepner’s restoration plan is dependent on the installation of a new irrigation system. The present system “ compromised of 1948 mainline pipe, 1961 additions, and 1987 computer software and sprinklers “ has been described by experts as outdated and underachieving.

‘It is imperative that in order to restore the essential design features of this fine Donald Ross golf course, the club must have the tools necessary to maintain the turfgrass at its optimum playing condition,’ wrote Hepner. ‘These designs were meant to play fast and firm. In order to provide dry conditions, the superintendent must have control of the water to be applied.’

Since his hiring in 1995, Andrejicka has markedly improved the condition of the golf course each season. With plans to install a state-of-the-art irrigation system and to restore Donald Ross’s original design on the horizon, Essex will soon be returned to its former grandeur.

The End