A Comparison and Contrast of the Donald Ross and William Flynn Routing Plans

for the Country Club of York

by

Wayne Morrison

Robert Crosby

Craig Disher

and Andrew Green

January 2020

If a list of great Golden Age Golf Architects is considered, William Flynn and Donald Ross would arguably be part of anyone’s top five. It is often said that golf architects of this period rarely competed directly against each other for design commissions. But on a quaint parcel of ground overlooking York, Pennsylvania we are given a tremendous opportunity to see how two of the best designers the game has ever known approached the exact same piece of ground. Why is this important? Well before mass earth movement was possible, the way golf architects used the ground shows us clearly how they used their vision and experience to create a journey over the available property to inspire a game that is defined by their routing.

Golf was introduced to York, PA by Mr. Grier Hersh in 1894 with a nine-hole course of 2,281 yards on his Springdale estate. Hersh introduced Mr. A.B. Farquhar to the sport and the two purchased 67-acres of land, leasing the grounds to the Country Club of York. A new nine-hole golf course was opened for play on July 1, 1900. By 1923, the club was interested in moving to larger grounds for a full eighteen-hole golf course and modern clubhouse. On January 12, 1924 the board of directors, led by Elmer Smith, authorized a committee to locate new grounds for the club. In early 1925, the club located the grounds in York and began the search for a golf course architect.

In late 1925 William Flynn and Donald Ross were asked to submit routing plans to the Country Club of York. Each visited the property and each completed his proposed routings at approximately the same time. Whether or not they knew it at the time of planning, they were participating in a design competition. To add an additional element to this story, another giant of the time, A.W. Tillinghast, was brought in to evaluate two separate properties – apparently prior to the commission of Ross and Flynn. Tillinghast seemed to value an alternate piece of ground from the one Ross and Flynn were asked to consider.

Local golf historians point to the preexisting Flynn courses at the Country Club of Harrisburg and especially the rival Lancaster Country Club as influencing the membership in York to select Ross. Lancaster Country Club hired William Flynn to modernize their golf course in 1920. Flynn produced a solid design, which he continued to improve, as consulting architect, over the next twenty-five years. The men of York wanted a design by a different architect, the most famous one in the land, to differentiate themselves from these other two clubs. It is ironic to consider the central Pennsylvania clubhouses of Lancaster and York in the early part of the twentieth century were rivals like the houses of Lancaster and York in fifteenth century England.

The new course for the Country Club of York was constructed in 1926 based upon the plans submitted by Donald Ross. Now, more than ninety years later, that competition provides a unique opportunity to compare and contrast aspects of the Flynn and Ross design philosophies. At York it is possible to hold constant the things that typically make comparisons of architectural styles so elusive. The location of the clubhouse, maintenance buildings, parking lots and access roads were all set at the time the two designers submitted their work. The differences in their routings are solely the result of different design preferences and philosophies.

As will become apparent in the discussion to follow, Flynn and Ross took remarkably different approaches to the County Club of York property and two remarkably different golf courses would have resulted.

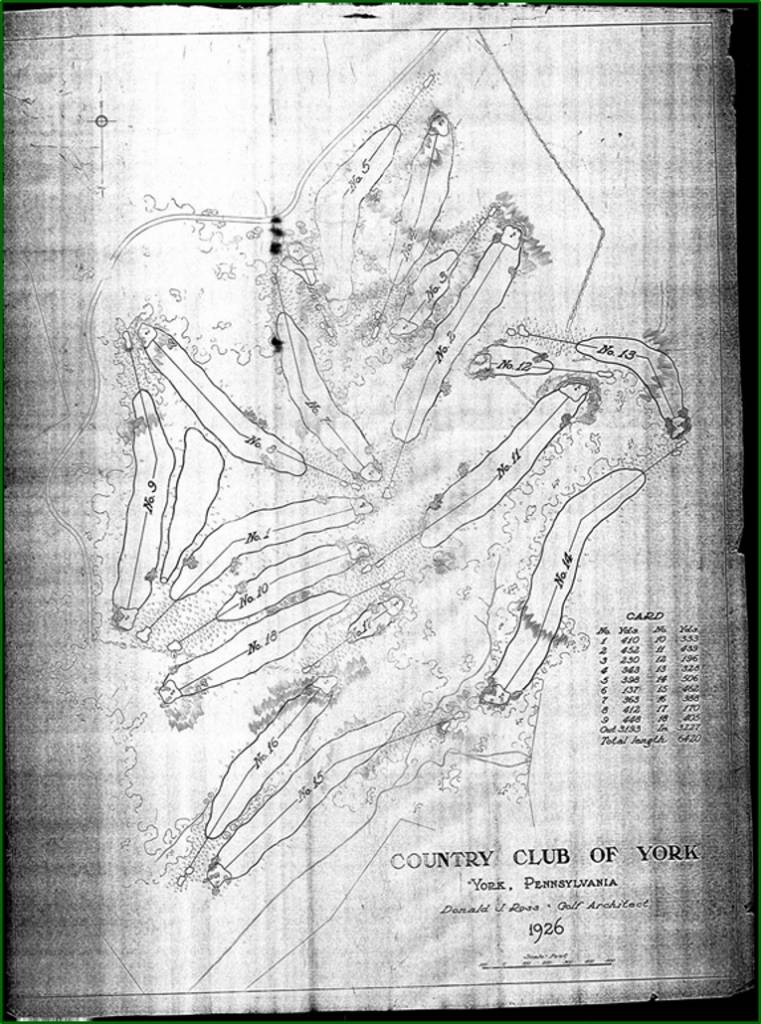

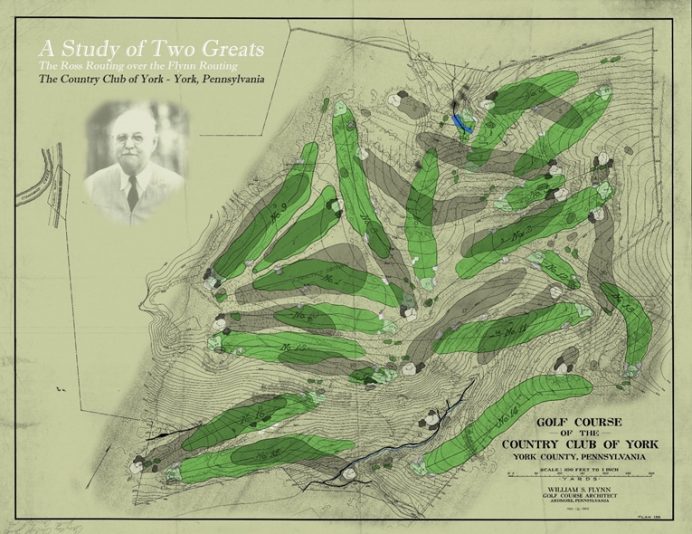

ROSS PLAN (GREEN) AND FLYNN PLAN (GREY) – Courtesy of Andrew Green

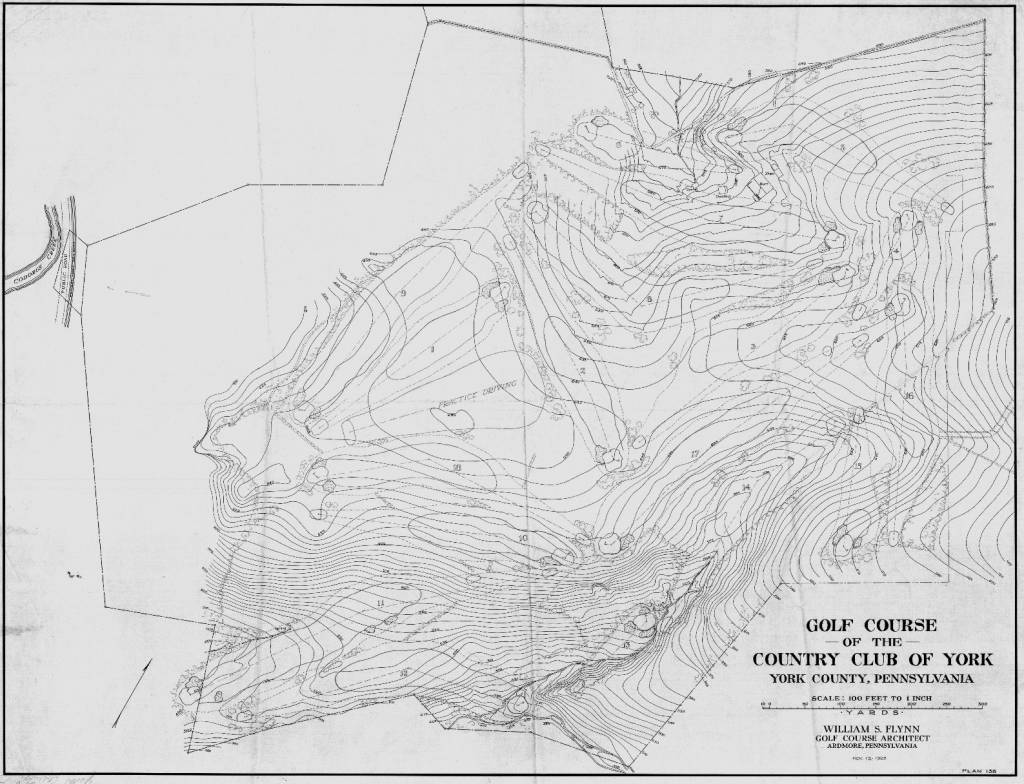

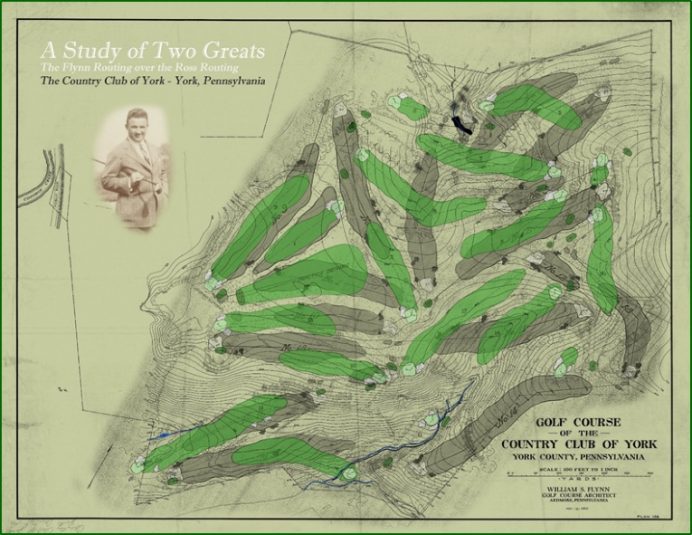

FLYNN PLAN (GREEN) AND ROSS PLAN (GREY) – Courtesy of Andrew Green

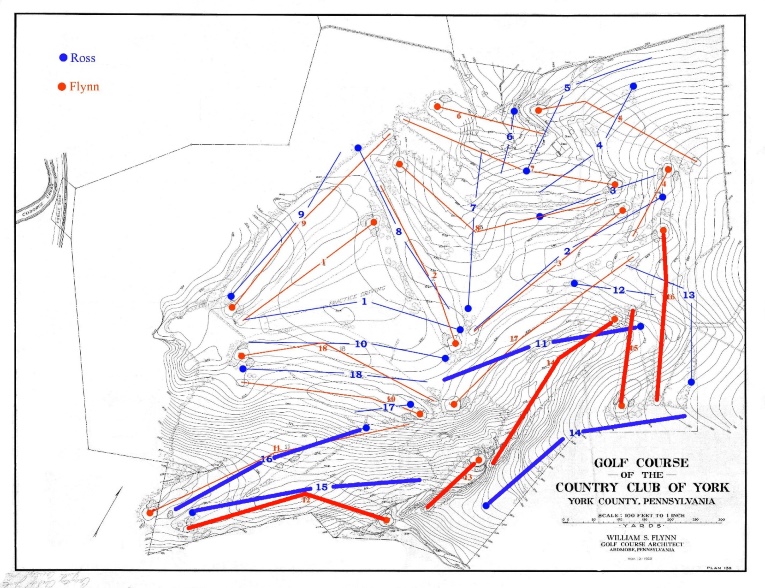

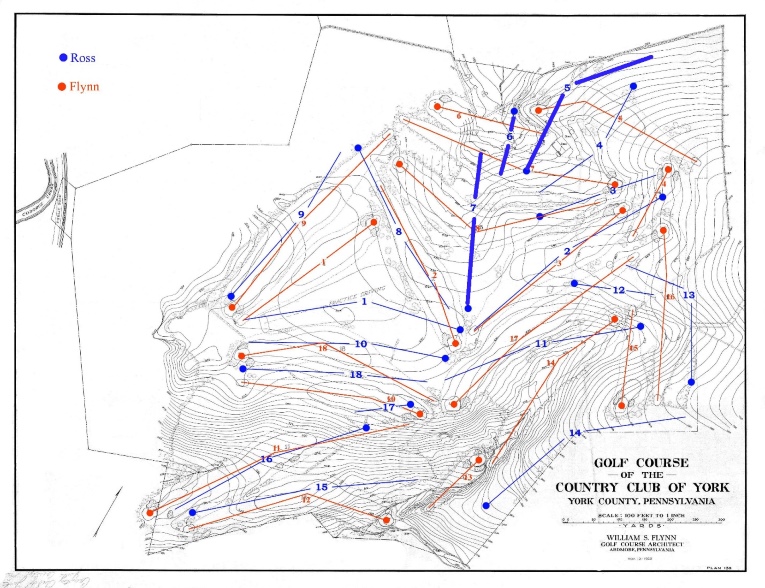

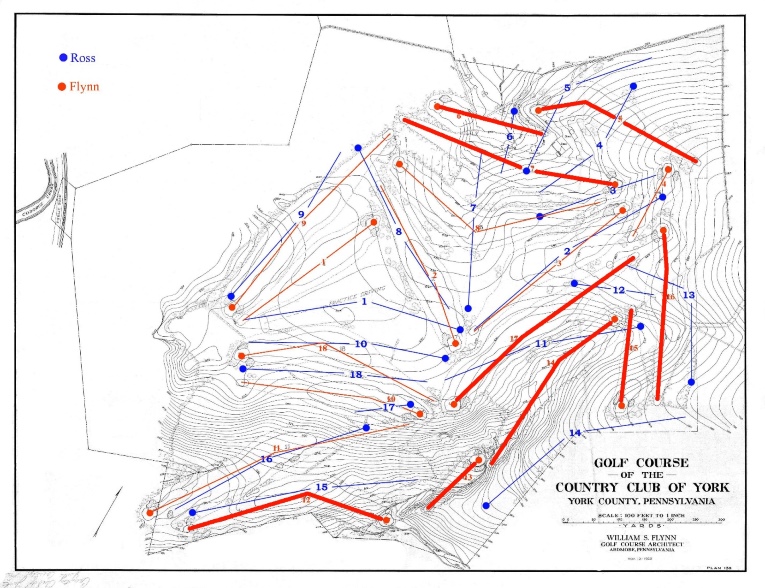

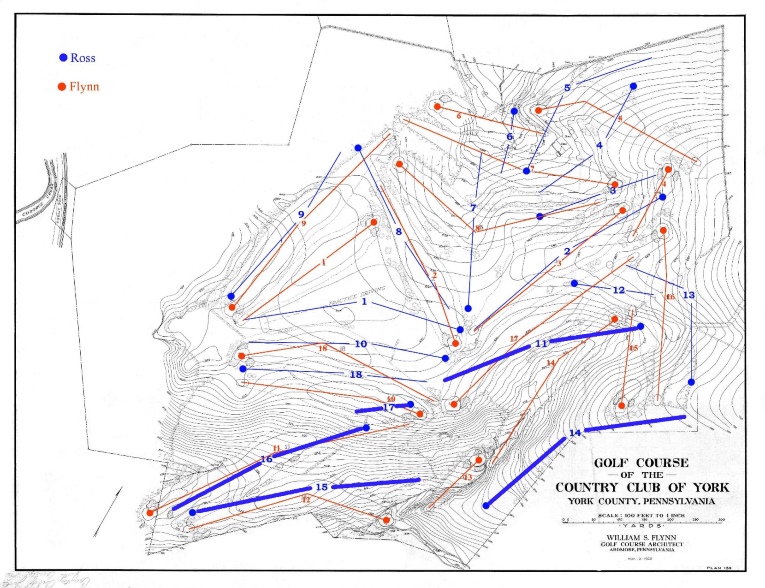

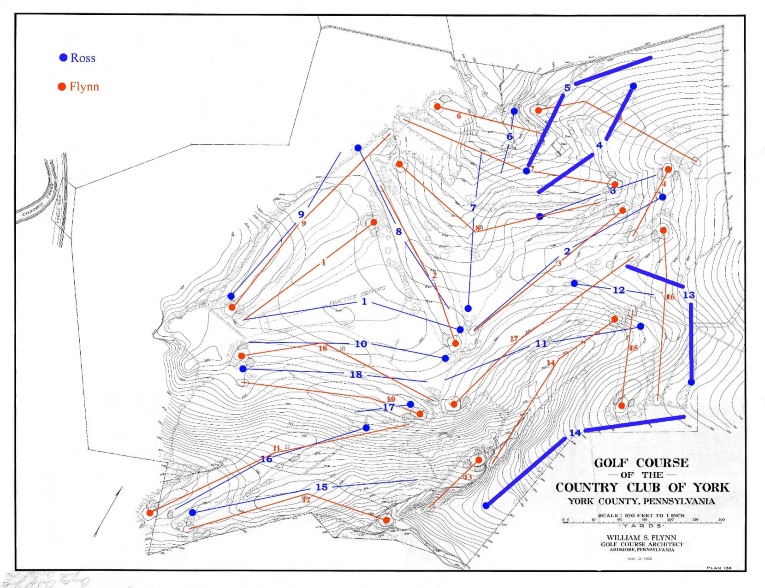

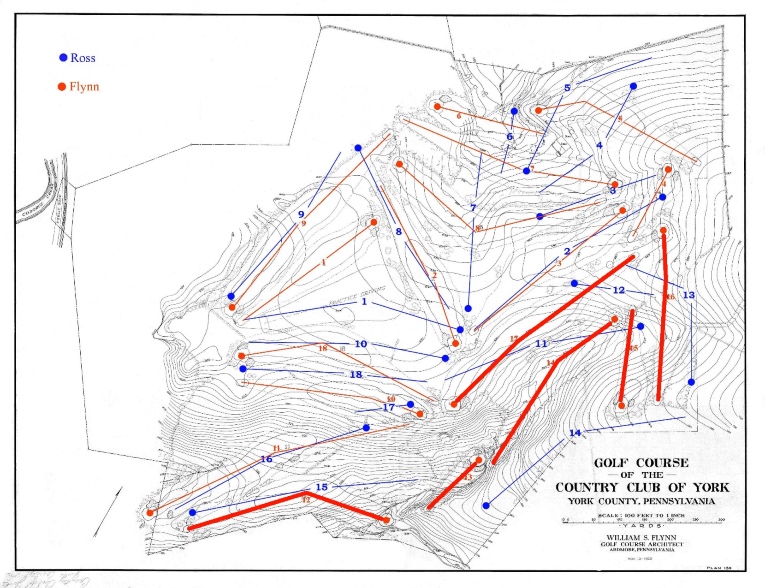

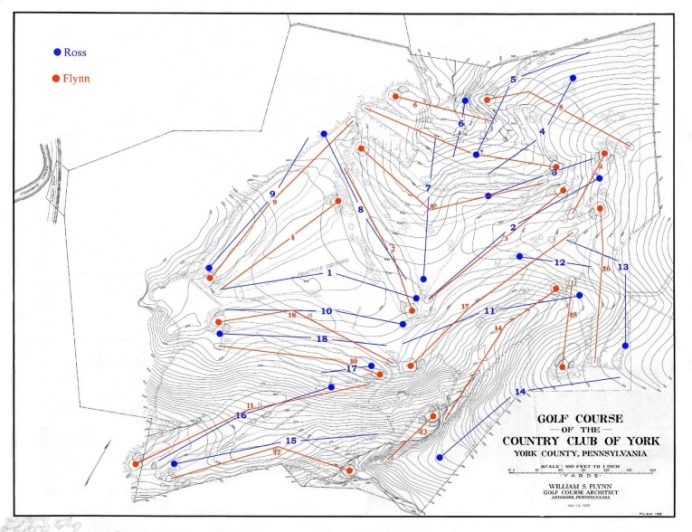

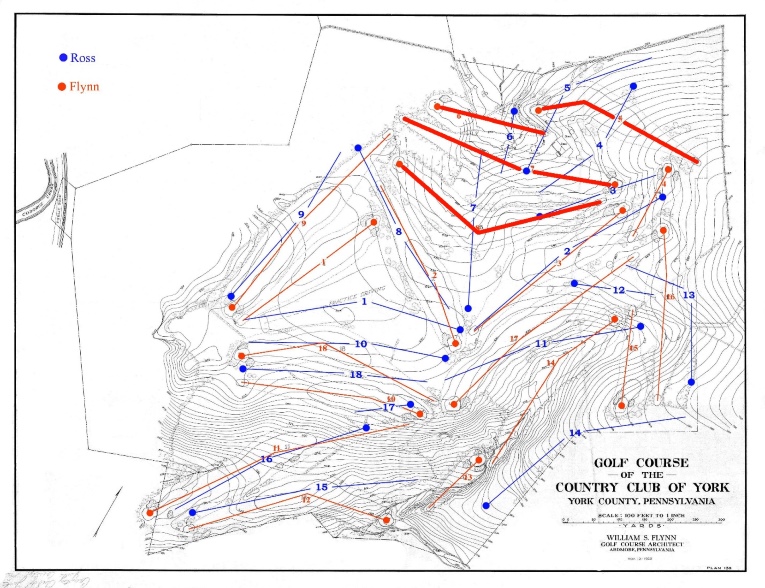

FLYNN ROUTING (RED), NOVEMBER 1925 WITH ROSS ROUTING (BLUE)

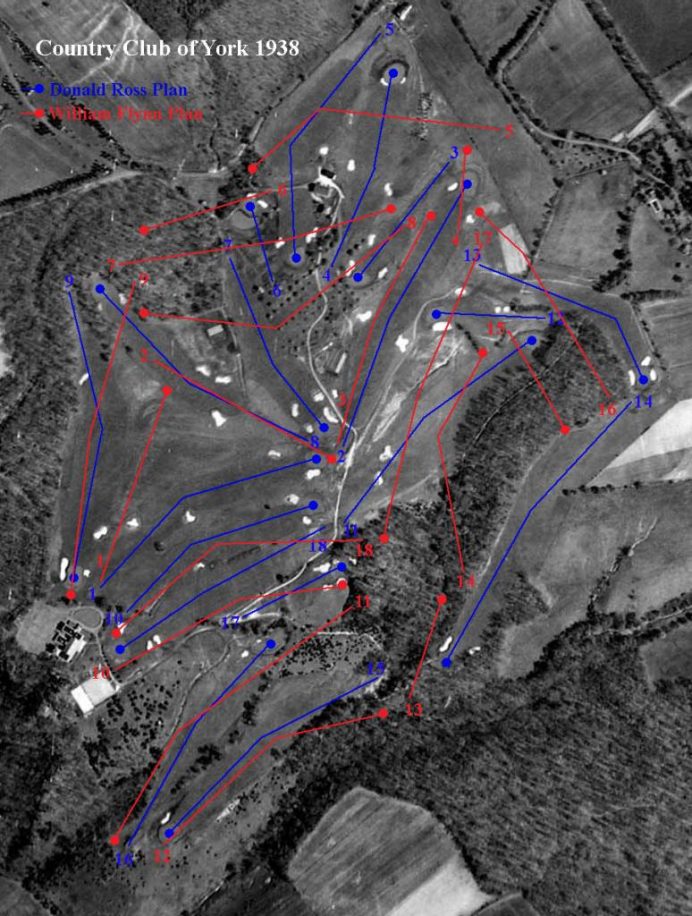

COUNTRY CLUB OF YORK 1938 SHOWING ROSS (blue) AND FLYNN (yellow) ROUTINGS – courtesy of Craig Disher

Ross versus Flynn – A Comparison and Contrast

Routing Plans

The routing plans submitted by Flynn and Ross were prepared in different formats and focused on different kinds of information. Flynn overlaid his routing plan on a topographic map of the York property. Flynn normally worked from a detailed base map and his York drawing reflects the specifics of the property’s contours and other features Flynn liked to have prior to construction. Ross did not usually overlay his routings on a topo, so the absence of a topo in his York routing was not unusual. His routing uses tick marks and hatching to indicate what he considered important landforms, providing less detail than Flynn, but perhaps giving a better sense of the flow of his proposed course. Ross also submitted detailed drawings for each hole. Like his routing plan, contour lines are not shown. We are unaware of any Flynn hole drawings though it is reasonable to assume that he prepared detailed drawings of individual holes precisely as depicted in the routing plan as he had in nearly all the plans in the collection retained by David Gordon.

The York Property

The Country Club of York property is dominated by an elevated plain beginning at the clubhouse in the southwest and continuing northeast for several hundred yards through the heart of the track. Another high ridge exits the property at its northeastern border. Two creeks mark the lowest elevations. It is an attractive setting for golf. Along the northern and western boundaries, the player would have overlooked an urban setting that was booming in the 1920’s. South and east of the property offered views of a pastoral landscape at the time the course opened and as it exists today.

The Golf Course

The very different golf courses Flynn and Ross proposed for the County Club of York in 1925 seem to belie the axiom that routing is destiny. Flynn and Ross came up with dramatically different routing solutions for the York property. The differences in their two routings highlight some of the distinctive architectural preferences of each.

Those preferences show up most obviously in the areas of the York property where the two architects concentrated their holes. The areas where Flynn located numerous greens and tees – in the rugged slopes, ravines and creeks found in the northeast and northwest – are the areas that Ross’s routing tends to have fewer holes. Conversely, the broad, relatively flat ridge in the middle of the property that served as the backbone for the Ross routing is an area that the Flynn routing seems anxious to move past.

Also striking is that few Ross and Flynn holes share the same ground while some were routed in opposite directions and others more or less perpendicular to each other. Note, for example the hole routings that cross in the northeastern and northwestern parts of the property. Part of the reason for the different hole orientations in those areas is Flynn’s desire for more dramatic holes that traverse or track along a ravine, a creek or other severe contours. Ross chose to orient more holes parallel to contour lines, suggesting a preference for less punishing and more walkable holes. Generally, Flynn used the difficult terrain while Ross tended to avoid it.

The two routings are so different that only one hole corridor occupies the same ground and also plays in the same direction. Flynn’s and Ross’s 9th holes take a similar path back to the clubhouse. Flynn’s 3rd and Ross’s 2nd also overlap to some extent. But that is pretty much it for similarly routed holes, something all the more surprising given the fact that the both routings had to use the same clubhouse location for the returning nines. It is also notable that even though the first tee is located at the same place in both plans, Ross’s first hole traverses an area Flynn reserved for a practice range while Flynn’s first hole traversed an area Ross wanted for his practice ground.

There are several holes where Ross and Flynn routed their holes in opposite directions. These include Ross’s 18th hole and Flynn’s 2nd, Ross’s 15th and Flynn’s 12th, Ross’s 16th and Flynn’s 11th, and Ross’s 18th hole and Flynn’s 10th.

Ross used more of the property’s periphery than Flynn did. The green for Ross’s 4th hole, much of the 5th and all of the 13th and 14th holes lie completely outside the perimeter of the Flynn routing. A great deal of this ground was gentler than the ground slightly to the west. It seems likely that Ross felt that holes at the edges of the property made for more flowing hole sequences. Flynn was more inclined to venture across and through some of the bold contouring, creating hole and green sites that would have been quite dramatic.

A key natural feature on the eastern portion of the property is a creek bisecting that half of the parcel that rests at the bottom of an amazing ravine. This is one of the defining landscape elements of the course.

Ross chose to orient holes 11, 14, 15 and 16 (bold blue lines) parallel to the creek while Flynn took the route of playing both along and over its dramatic contour. Flynn planned holes 12, 13, 14, 15, and 16 (bold red lines) using diagonal lines of play to get the player across the creek and up the low to the high point of the back nine. These angles were important to traverse the property effectively without it feeling too severe. It is surprising that Ross avoided that area completely. His 11th taking the most advantage of the low ground. However, when you stand on the current 11th tee, it feels that playing more from the right is comforting, similar to the way Flynn positioned his 14th.

It is hard not to conclude that the Stream Valley was a feature Flynn saw as having the most design potential. He was not a stranger to crossing streams in his hole designs. Several examples include Manufacturers Golf and Country Club which has eight holes crossing streams, Lancaster Country Club has six, Lehigh Country Club has four and Huntingdon Valley originally had eleven of twenty-seven holes crossing streams. At these courses, the angles of play and use of water rarely forces a player to play a particular shot but gives them a chance to pick a line of play and distance to be bold. If successful they are rewarded…if not, trouble awaits.

Ross tended to be less likely to take such routes. But it is clear that he used creeks in some of his most widely regarded designs. He used Allen’s Creek at Oak Hill to route the East Course around the same time as his Country Club of York design. It makes one wonder if he even saw the opportunity Flynn saw in the low ravine, or he felt holes like 14 and 15 were too compelling along the higher ground?

In the northeastern quadrant, there were different approaches to the severe contours that mark a spring and small rambling creek. Ross routed his holes 5, 6, and 7 (bold blue lines seen below) in roughly a north/south orientation.

Meanwhile, Flynn’s holes 5, 6, 7 and 8 (bold red lines seen below) ended up in the same quadrant but he oriented his holes in an east/west direction. We see that Ross again placed his holes parallel to slopes while Flynn went against the grain, routing across contour lines. One result of Flynn’s routing is that Flynn used the difficult terrain while Ross tended to avoid it. According to Andrew Green, “Flynn’s holes may have been more memorable but Ross’s probably worked better on the ground and were probably more cost-effective to build.”

Some of Flynn’s choices for green sites are in low areas which Ross avoided. While these areas would result in greater periods of shade and reduced air circulation due to the higher surrounding elevations to the south and east, given Flynn’s considerable agronomic experience and skill, it is doubtful there would have been turf management issues. It is hard to tell if the committee at York considered this as an issue in the selection process.

Routing a golf course is similar to stacking dominoes for a chain reaction. The first hole leads into the next and into the next. Both men were charged with or felt strongly about returning nines. Therefore, how they used the central part of the property largely was an implication of how the exterior pieces fit. If you have to start and stop each nine at a set point, how you journey out and back generates all the differences.

Golf Architects tend to use three elements – tee locations, green locations, and the connection between the two – in routing and depending on how strongly they feel about each hole each component effects the next. Architects tend to fall in love with holes or ideas when they study a piece of ground and often something that sparks their attention impacts the remaining holes. To truly understand how these men worked through the larger portions of the property it is helpful to consider their use of the two principal topographical features of the Country Club of York property.

The Central Plateau

As noted, a broad, elevated central ridge dominates the middle of the County Club of York property. It is a relatively flat plane and serves as the central hub for Ross’s routing. He located no less than four greens and four tees in this area. The associated holes that fan out from this high ground form a sort of hub and spoke pattern. In fact, Ross’s overall layout rotates, in a general way, around this area.

Flynn placed only his 2nd green and 3rd tee in the central plateau, using little of this property in his routing. It appears that Flynn made a determined choice to utilize the severe ravine mentioned previously due to its exciting potential and he had to route the other holes to connect into this space. The result was only a few holes were needed on the high ground.

Ross also located his 1st and 10th holes, just to the west of the plateau, on the flattest part of the property. Flynn again bypasses the area, reserving most of it for a practice range.

The Northeast Ridge

If the central plateau area serves as a focus of Ross’s routing, a broad ridge running north/south through the ridge in the northeast corner of the County Club of York property serves as the area of Flynn’s focus. It is at approximately the same elevation as the Ross hub in the center of the property. Flynn locates four greens and four tees there. But rather than serving as a central hub as Ross’s does, Flynn’s preferred high ridge serves as a hub for several holes that traverse the severest topographical features on the property.

The southern half of Flynn’s central area provides a platform for tees and greens that set-up the holes crossing the deep creek bed cutting through the eastern side of the property. The northern half of the ridge connected his routing back to the larger portion of the course. By using this entire area, the depth of the ravine shallowed moving north and uphill generating different golf shots even when playing near or parallel to previous lines of play. Flynn’s concentration of tees and greens on the northeastern section served as a long, elevated platform on whose axis Flynn placed tees and greens for adventurous holes routed across very difficult terrain to the south and northeast. This was a genius part of his routing.

Ross utilized this ridge mostly for his great par 5 second hole using the top of the ridge as a hogsback off the tee and then the left side of the ridge for the second half of the hole. The eastern slope is the site of the par 4 eleventh that rests between the high ground and the valley below. The 12th then crosses the top and sets up the home stretch along the eastern perimeter of the property with holes 13 through 15. These holes work well and allow the golfer to move through the steep topography in a gradual manner. The Ross routing progression makes the trek from low ground to high ground a bit more gracefully than Flynn’s.

Ross hole designs of note

Ross’s 7th hole covered ground that was completely avoided by Flynn. The short par 4 played straight uphill starting at an elevation of 580 feet and climbing to a green site at 645 feet over its original 363 yards.

Like the 7th hole, Ross positioned his 14th hole on ground completely avoided by Flynn. Ross designed the 506-yard par 5 14th hole extending beyond the eastern edge of the Club’s property as depicted in the topographic map. The dramatic hole began at an elevation of 685 feet to a landing area 50-feet below with the green at an elevation of 540 feet for an overall drop of 145 feet. The ground also falls sharply behind the intricate Ross green.

Ross’s 16th hole plays in the opposite direction of Flynn’s 11th hole. The Ross hole plays in a northerly direction starting at an elevation of 500 feet climbing to 585 feet over an original 388 yards. Flynn’s hole played in a southerly direction starting at an elevation of 610 feet and finishing at 500 feet for a drop of 110 feet.

Flynn hole plans of note

Whereas Ross incorporated 52 bunkers for his hole plans, Flynn used half that number in his initial plan. Flynn called for 26 bunkers in total with a mere 2 fairway bunkers, both on the eleventh hole. Where there was topographical interest, Flynn would often use fewer bunkers and allow the influence of the ground contours to dictate his routing and hole plans creating strategy and shot testing opportunities – the golfer may be called upon to ideally hit a fade off a draw line or a draw off a fade line; or have a canted fairway require the golfer to shape a shot for maximum gain off the tee or on the approach where there may be an aerial demand or ground game option.

Three very different hole designs had no bunkers in his initial plan. The flat 8th hole, the 40-foot downhill 12th with its green sitting in a bowl just beyond the crossing stream, and the 90-foot uphill 14th with the tee shot played to a plateau leaving a 40-foot uphill approach.

The short 13th hole is somewhat reminiscent of the 13th at Merion’s East Course with bunkers and a stream surrounding the small green. Flynn’s 12th at CC York is similar in design to the excellent 11th at Huntingdon Valley Country Club, both greens sitting in a low area with a stream fronting the green.

The 350-yard 16th played over a valley to a green level with the tee. The fairway cut was continued along the entire right side of the green allowing both an aerial and ground game shot option. The longer player could approach the hole with an aerial shot on the short par 4 if conditions allowed while the shorter player had the option of running the ball onto the green and allowing the surrounding slope to feed the ball onto the green, especially for hole locations on the left side of the green.

Summary

Both Ross and Flynn incorporated practice areas, which, as stated earlier, is great to see in 1925. It is clear in review that the Flynn plan for practice was more functional. The Club used the Ross practice area for years but ended up abandoning it to construct a bigger facility on the opposite side of the clubhouse. Flynn’s 280-yard range may not be long enough for the modern game but it would have given the Club an opportunity to update the proposed facility today.

Both architects designed an excellent set of par 3 holes with a nice mixture of topography, compass direction and a mixture of right to left and left to right shot preferences. Each nine features holes with a nice variety of directions, a more difficult accomplishment that golf architects understand very well but a fact that is rarely considered by anyone that hasn’t routed a golf course.

Flynn had far fewer parallel holes than Ross, but the utilization of topography forced decisions to get each nine to fit. Once a determination was made to play a certain direction, the other holes had to fit. Flynn decided to cross contour lines much more so than Ross. This would have made the Flynn routing a more difficult walk while offering more variety and maximizing the use of elevation change as a factor in shot selection and distance control. It is interesting to imagine that this was discussed in the selection process. Having a differing philosophy on this large of scale gave the decision makers a great deal to consider.

In the end the respective routings highlight two very different architectural approaches to the Country Club of York property specifically and to golf course design generally. Contrary to the old axiom, the competing Flynn and Ross routings for the Country Club of York property prove that topography is not destiny. Flynn and Ross routed and designed radically different golf courses. Areas on which Flynn located numerous greens and tees were areas that Ross skirted. Similarly, areas around which Ross centered his routing were areas that Flynn barely used.

The members of the Country Club of York realize that their history was marked by this competition and they embrace their connection to both architects. The reality is that the Elmer Smith and crew could not go wrong with either choice. While the membership loves playing their Donald Ross gem, it is fun to think about what would have been with the Flynn holes.

How differently would these two courses play? Flynn’s routing is the bolder of the two. The most difficult terrain on the Country Club of York property was at the heart of Flynn’s routing, and the resulting holes would have been challenging even for the scratch golfer. Flynn proposed that the 5th, 6th, 7th, 12th, 13th, 14th, 15th, 16th, and 17th holes (bold red lines) all either traversed creeks or had green sites perched next to steeply sloping creek beds. These holes would have involved testing carries or features at the green that would have severely penalized mishits. These supreme shot testing holes would have been difficult for the weaker player, they also would have formed the heart of a thrilling, championship test for the strong player.

Ross’s routing reflects a very different architectural perspective. If Flynn routed eight holes across or near creek beds on the Country Club of York property, Ross largely avoided those areas. On the routing comparison aerial and the above stick routing map, note the wide gap in the Ross routing between the line formed by his 14th and 15th holes and the line formed by his 11th and 16th and 17th holes. That large area completely unused by Ross, is the creek bed that Flynn makes the centerpiece of his design.

At the Country Club of York, Ross sought to route holes along contour lines while Flynn selected opportunities to route against or perpendicular to contour lines. Certainly their disparate treatment of the creeks and their steep surrounds bears that out. But it can also be seen on the holes Ross routed at the edges of the property. His 4th, 5th, 13th, and 14th holes lie well outside the perimeter of Flynn’s routing, all running along the property’s boundary lines where contours are gentler. Again, Ross elected to use the flatter terrain for the mid-bodies of his holes. In contrast, Flynn’s routing sought to incorporate some of the severest terrain on the property for his mid-bodies. As a consequence, the Ross routing was probably both more forgiving for the weaker player and easier to walk, considerations that clubs like the Country Club of York might have given great weight in their architect search process.

The extraordinary boldness of Flynn’s proposed 12th through 17th is remarkable. His 12th fairway would have dropped to a green diagonally fronted by a creek. The par three 13th would have climbed out of the creek bed to a green perched into a slope, its right side guarded by a steep fall-off with the creek at the bottom. The 14th would have been a long, steep uphill (90-feet of elevation change) par four routed through a heavily wooded gorge. The 15th, a par three, was uphill again to an offset green. The 16th would have started with an elevated tee, dipping into a small depression mid-hole, and back uphill to a well-bunkered green. The 17th would have tracked back along the western edge of the creek, the fairway sloping hard from right to left, requiring a fade to hold the fairway, culminating at a green benched at the edge of severe left-side fall-off. These would have been tough, exciting and beautiful finishing holes. Severe shot demands would have been encountered on every shot.

Ross’s reluctance to engage such hazards so directly in his designs is consistent with his view that greenside water and other greenside hazards should be used sparingly. He also eschewed forced carries and tried to avoid them if possible or minimize them when the land gave him no choice. It seems fair to say that Ross’s courses tend to be more forgiving from tee to green. He preferred to concentrate his hardest challenges at the green. Consistent with those views, the Ross routing for the Country Club of York property minimized the use of the property’s most severe natural hazards, but his greens at the Country Club of York are enjoyably challenging.

We hope that you take the time to study the two routing and provide your thoughts on how you feel the two designs compare and what things you like and dislike about each. It is fun to think about the conversations that occurred in 1925 both inside these architect’s offices and at the Club board room table.