H.C. Leeds, the Papa of American Golf Architecture

by

Kevin R. Mendik

August 2016

Herbert Cory Leeds[1]

Herbert Cory “Papa” Leeds was born in Boston on January 30, 1855, son of James and Mary Elizabeth (Fearing) Leeds. He prepared at Hopkinson’s School in Boston, then attended Harvard College from 1873-1877, receiving his AB degree in 1891 upon completion of his examination the previous year. He had a strong build and was active in many sports, playing on the baseball nine for four years and on the football eleven in 1874 and 1875. In 1875, Mr. Leeds scored the first points in the first Harvard Yale football game and they would prove decisive, as Yale failed to put any points on the board. He was a highly intelligent man, yet he was guarded about his achievements, listing no occupation on his Harvard Class Reports. He never married, but was survived by two nephews and two nieces.[2]

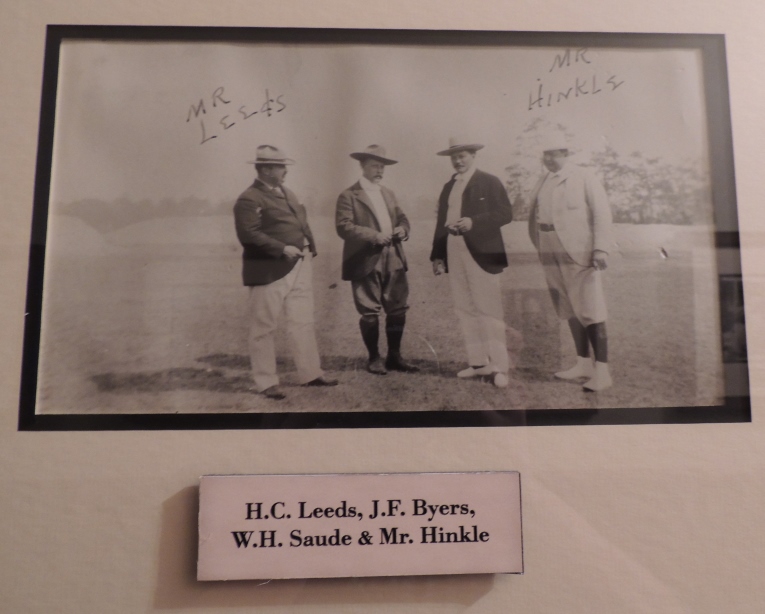

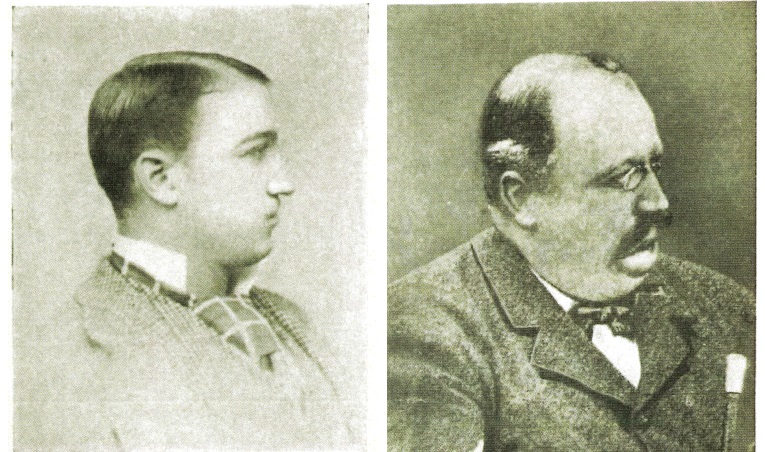

Leeds at Harvard 1877 at Left, 1927 at Right. Courtesy harvard University Archives HUD 277.40 Leeds was rarely photographed. Below, Leeds at Palmetto, circa 1900.

After completing college, he traveled extensively through China, Japan, Java and India and spent a year in Paris. By 1885, he had also visited the Western United States and the West Indies. He was an established bridge player and penned two books on the subject.[3]

He spent three seasons sailing in Cup races, each time with C.O. Iselin: first in 1893 on Vigilant in the International Cup Races with Valkyrie, and again in 1895 on Defender in the Cup races with Valkyrie III. Leeds was on Columbia in 1899 with Shamrock, where he wrote the Log of the Columbia Season of 1899.[4] In 1901 he was again on Columbia as a guest of Harvard classmate E.D. Morgan.

When the game of golf came to the Boston area in the early 1890’s, Leeds was quick to take up and excel at the new sport. He won The Country Club’s first Championship in 1893, going around the nine-hole course in 109, defeating Laurence Curtis by a single stroke. He won again in 1894, this time with a score of 110. He was also listed on TCC’s Committee on Shooting in their 1883 year book.[5]

At that time only a handful of courses existed in the Boston area: Pride’s Golf Course was relatively flat; the Essex County Club had 6 somewhat more difficult holes, TCC had 6 at a cost of $50 and soon added 3 more, followed by the nine at Myopia in 1894. There was often considerable opposition to establishing golfing grounds from the equestrian perspective, but fortunately at Myopia, there were some key proponents of golf. In 1894, there were less than 50 courses in the U.S.; by 1900, there were over 1000.

Early in 1894 when the snows had melted, Mr. R.M. Appleton, the newly elected Master of Fox Hounds at Myopia, along with Squire Merrill and A.P. Gardner, paced off distances from tees to rudimentary greens. The Executive Committee met in March, nine greens were sodded and cut and play began around the first of June. From the start, the grounds for golf at Myopia were hardly typical of relatively flat and open grounds chosen by most other clubs. The ground was rough with thin soil, fertilized by generations of cattle. The ground was rolling and required a few blind shots, the rough was horrendous and the greens had treacherous slopes. Sheep cropped the fairways.

Leeds traveled to Bar Harbor, Maine in early June 1894, expanding an existing 6-hole course laid out around a race track into a formal nine-hole course at the Kebo Valley Club.[6] The course was referred to in a news account of the day as being 1 & 3/4 miles long, or just under 3,000 yards. He returned in time for Myopia’s first tournament (25 players) on June 18th, and won with a score of 112; Mr. Curtis again coming in second with 122. Leeds also won the second tournament on July 4th, this time with a 113, and won again at The Country Club, with a 110.

He was on the team that represented TCC in the first interclub matches held in the U.S. at the Tuxedo Club in New York. TCC’s team brought home the cup, which resides today at the U.S.G.A. Museum. There is some question as to the exact date of the match, but the date on the cup is September 24, 1894.

Leeds continued to play in interclub and early International competitions, including those between TCC and Royal Montreal.

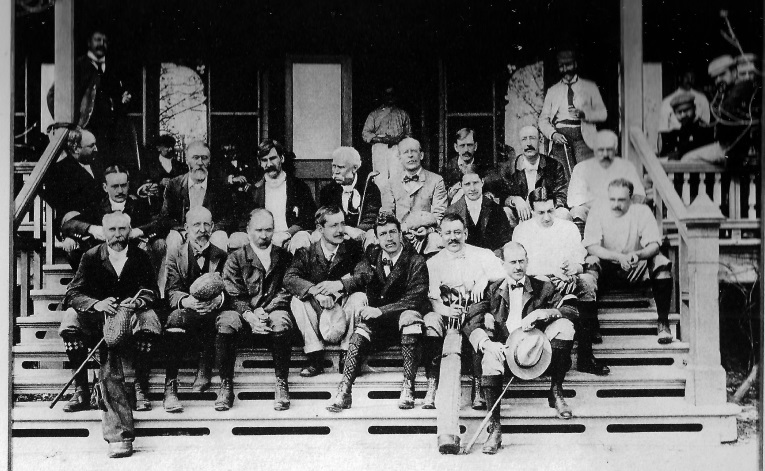

Leeds, with TCC’s team in May of 1898. Leeds, at top left is showing his right side, this is how he appears in virtually every known photo of him. Photo from Curtiss, 1932.

Leeds used mounds in many locations at Kebo Valley, including fairways above, and greenside.

Intricate bunkering behind the green compliments the mounds to be cleared on approach, as seen below.

In early 1895, Leeds traveled to The Palmetto Club in Aiken, South Carolina and assisted in bringing their initial 4 hole course up to nine holes at 2,278 yards. The first Southern Cross Tournament was held at Palmetto that summer; Leeds won the second and fourth contests in 1896 and 1898. Leeds was among many Boston area residents who traveled to Aiken for the winters.

Between 1895 and 1897, the course was expanded to 18 holes by himself and Scottish professional Jimmy Mackerell, Palmetto’s first professional. The greens were made of sand, relatively uniform at 60 feet in diameter and perfectly level, but the course was considered extremely challenging.[1] The terrain movement and hazards are reminiscent of Myopia, but today’s bunkering and greens show the work of Dr. MacKenzie.

Here as well, Leeds took advantage of the terrain he found, incorporating ravines, creeks and stone walls. He added cross and greenside bunkers as deep as four feet. One green was on a hillside, protected by a bunker with a ravine behind the green. Others had stone walls and roads close up. The holes had names like “Crazy Creek” and “Rat Trap,” and some were described as “puzzling” to play.

Tight greenside bunkers on this elevated par 3. Tee is at far right out of frame so this bunker must be carried.

Pamletto’s terrain offered considerable movement along with underlying sandy soils. Both Leeds and MacKenzie shaped bunkers and utilized natural waste areas.

In 1896, Leeds joined the Myopia Hunt Club, was promptly appointed to the Golf Committee, and asked to lay out what would become known as the Long Nine.[1] He was Myopia’s Club Champion that year, the only year he held that honor. In 1898, he again won the Southern Cross and was the low amateur in the 1898 U.S. Open played at Myopia, the first of four such contests held there during the next 11 years (1898, 1901, 1905 and 1908). Reviews by the contestants and the media provided equally high praise of Leeds’ work there.

In 1898, Leeds also won the Myopia Handicap Cup, a large crystal and silver cup which was purchased at auction in 2008 and returned to the club the following year. It resides in the clubhouse along with many other pieces of Myopia’s historic competition fabric.

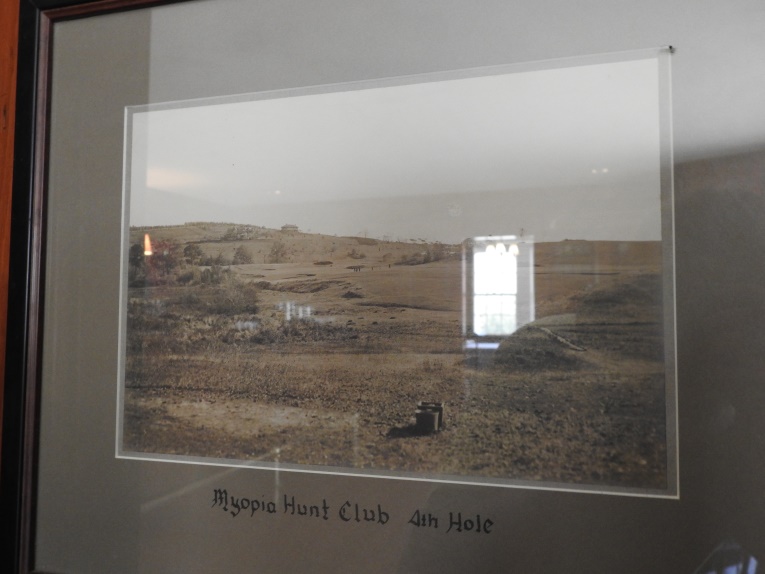

Myopia pre-1903 above shows the open nature of the terrain. The players are on the original 4th hole, which today is in the area between the 10th and 11th holes. Courtesy Myopia Hunt Club, MDR.

The fourth hole continues to confound those who leave the approach short. The green is among the most treacherous with many a putt ending up in a bunker.

The area between todays 10th and 11th holes again resembles its historic conditions. Players on the long nine would hit over the large mound (Pre-1903 photo) and play left around the oak tree; followed by a sharp dogleg right up to today’s 11th green.

It is important to note that there was virtually none of what we consider golf architecture in most early American courses. While there were a few Scottish transplants such as Alexander Findlay and Tom Bendelow, the land they worked with was more often flat or gently rolling, was taken as it was found, holes were straight with perhaps a stone wall or two coming into play.

Leeds was determined to use whatever the terrain offered in terms of challenges. Whenever he could use sloping or undulating terrain, he’d place a green. A great description is found in Mr. Week’s book at pages 34 and 35. Leeds dug out areas around greens, using the material for mounds. He collected stones from walls and made more mounds. Other walls he left intact or would mound one side. Bunkers were carved. Given that Myopia has had a longer tradition of equestrian activities than golf; it is not unlikely that Leeds drew many of his ideas from the steeplechase where walls, water hazards and undulations in terrain are omnipresent.

The course he developed during 1896 and 1897 played to 2,928 yards. At that time, the best players could hit a ball 175 yards which might include 50 yards of roll if the sheep had been out. At a long drive contest held during the U.S. Open in 1899, Willie Hoare won the contest with a poke of 270 yards. This distance may have been achieved with the new Haskell ball.

Myopia was understandably proud of their course, and offered it to the newly formed U.S.G.A. as the site of the 1898 U.S. Open. Liking what they saw, the date was set for June 17 and 18, 1898. The 1898 contest was the first U. S. Open to require medal play (72 holes), as well as the first time the Open and U.S. Amateur were held on separate courses on separate days, the Amateur still being match play.

In those days, the professionals were considered workingmen and were not permitted into the clubhouse. A marquee was set up around where the present 18th green is to allow them to change, eat between rounds and perhaps have a beverage or two. Several came in from overseas for the event. Scotsman Fred Herd won the event with scores of 84, 85, 75 and 84 (328). This was with considerable wind (only 28 of 49 in the field finished). Leeds was low amateur, tied for 8th with a 347, and shot 39 on the first nine.

The Long Nine at 2,928 yards was considered among the most challenging in the country as evidenced by numerous newspaper accounts of the day. Leeds was largely responsible for expanding the course to 18 holes, undertaken during 1898 and 1899. British Champions Harry Vardon and J.H. Taylor played the new course in the spring of 1900, and while Taylor set a new course record of 78, Vardon had a less than stellar time of it and later stated in his autobiography My Golfing Life that while most American courses “suffered from a lack of bunkers,” Myopia was “unfortunately rather spoiled by an excess of them.”

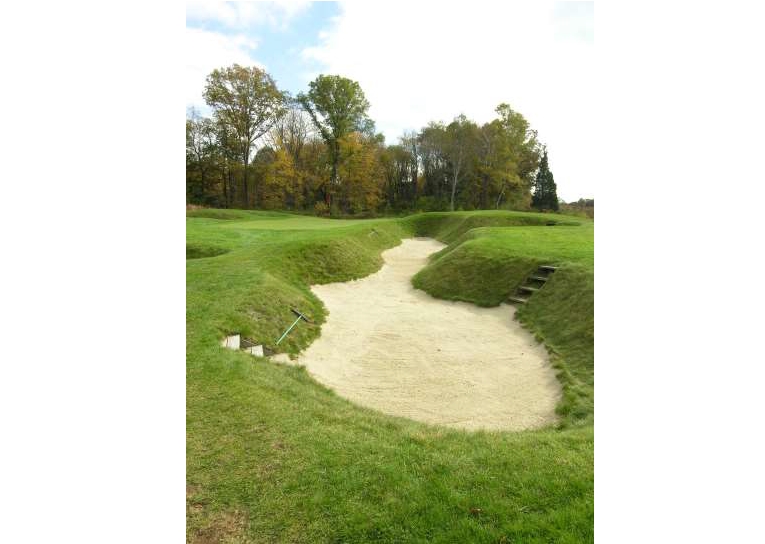

The par 3 9th hole alone (#3 on the Long Nine)[2] includes 7 bunkers, all accessible by stairs. The entire green complex including the bunkers was shaped from materials excavated from the area that is now the pond. This is the only place on the golf course where this type of considerable earth moving and shaping was done. That this green complex was constructed well before 1900 offers testament to Leeds’ vision and talent as a golf architect. While it is not clear where Leeds got the inspiration for its features, Myopia’s 9th hole is widely considered among the great American par three’s.

Myopia’s 9th, the original 3rd hole, remains one of America’s most iconic short par threes. The hole is that more exceptional given it does not have a template hole in the UK or Continental Europe.

Far more complex than most short par 3s, the bunkering presents tight challenges as well as those often found in approach bunkers; the front right bunker extending almost 20 yards from the putting surface.

Scotsman Fred Herd won the event with scores of 84, 85, 75 and 84 (328). This was with considerable wind (only 28 of 49 in the field finished), Leeds was low amateur, tied for 8th with a 347. He shot 39 on the first nine. The Boston Journal noted that the scores “prove conclusively that no player can average better than 40 strokes on a course of over 3,000 yards.”

Through the 1890s, players were still using gutta percha balls which tended to soften up as they got warmer. They played the ball down as it was found. The rough was pretty much like it is today. No cleaning the ball or repairing ball marks before putting. Most bunkers still had hard pack or dirt; if there was sand, it wasn’t raked. That the course remained challenging enough for top level play beyond the 1899 introduction of the Haskell Ball is further testament to its advanced design.

Following the 1898 Open at Myopia, Leeds persuaded his fellow golf committee members to utilize club lands not already devoted to golf and well as purchase additional lands in order to make “a proper links.” Over the next two years or so, Leeds’ vision came into being and is largely the course that we play today, although he would probably be disappointed that not all of his bunkers remain. He challenged players with earthworks and cross traps before greens, he penalized short hitters with features like the angled bunker on today’s par three 3rd, still a two shot hole for many golfers. He gave long hitters options to cut corners on holes like the fourth. He utilized horses with padded hooves to pull grass cutters on holes such as 5 and 6 where the turf was often wet due to the brook which still comes into play today.

The short ninth continues to confound golfers with the deep bunkers surrounding the green, and requires a shot over the bulrushes.

To the left, the author in familiar territory in the Taft bunker on 10, an unlikely place from which to make par. To the right, the bunker guarding the tenth is still deep enough to hide all but one’s cap.

On today’s 12, Leeds utilized a challenging mound for his green site. Thirteen was lengthened and no longer plays over the pond now surrounded by forested wetlands. Leeds wanted the challenge to be on the approach to the green, and was apparently never quite satisfied with what he considered a plateau green, having envisioned the green higher up on top of the ridge, (see 1913 and 1923 maps below). Fourteen was considered one of the most bunkered and challenging holes in the country, having a dozen bunkers, several mounds and of course the ubiquitous rough.

On 15, he built four foot high earthworks in the fairways and a yawning trap in front of the green, now with an opening in the middle. Leeds lengthened the 16th (originally the 9th) by adding 90 yards, making it a blind par four. He gave in on that one after too many complaints about Myopia’s abundance of blind shots, and restored the hole to the downhill par three in play today. The new eighteenth provided a risk reward that continues to challenge players with deep bunkers in front of the green. He left an entrance (photo below) for the occasional lucky shot.

During Harry Vardon’s 1900 golfing tour of the U.S., he visited Kebo Valley and Palmetto. He remarked that the greens at Kebo were the finest he had seen in the country.[1] At Palmetto, Vardon played a match against the best ball of Leeds and H.R. Johnstone, defeating them 9 up.

Leeds also collaborated with golf professionals and architects John Duncan Dunn and Walter J. Travis to revise and expand the existing 9-hole course at the Essex County Club in 1900.[2]

The second U.S. Open contested at Myopia was in 1901, and it was the last such event where the new Haskell ball was excluded. The winning score was 331 shot by Willie Anderson; no one broke 80 the entire tournament. Mr. Anderson won the U.S. Open again the following year at Baltusrol with the Haskell ball and a score of 307.

In 1902, Leeds as the “mentor of Myopia”[3] traveled to the United Kingdom to have a firsthand look at the great Scottish links courses, which makes his pre-1900 work that much more impressive. Although this was not his first trip to the United Kingdom, it was the first time he went with an eye focused on its golf courses.

Weeks notes that Leeds’ experience in the UK in 1902 left him convinced that his design for Myopia was sound,” but that new tees and especially hazards were warranted to deal with the new livelier rubber-core Haskell ball. It is important to note that when Weeks wrote his 1975 chronicle, he had access to Leeds’ personal journals, which have not been located. Clearly, Leeds left many detailed impressions and the hope is that those journals will resurface.

Photos were likely available of courses across the pond, although their clarity may not have been ideal; other ideas could well have come from the Steeplechase, as many early American golf courses were laid out where hunt clubs existed before golf arrived. Myopia was originally located in Winchester at the current location of the Winchester Country Club, but the club moved to its present location in Hamilton as the terrain was considered better suited for Steeplechase. Turns out it also worked rather well for golf.

After his visit to the UK, Leeds continued to revise the Myopia course based on the direct influence of what he saw in the UK, with impressive results. Myopia was far more challenging than anything golfers who had not played the game in the British Isles had experienced, as expressed in a 1903 description in Golf of collegiate matches with teams visiting from the U.K.[4]

The Massachusetts Golf Association was formed in 1903 with Leeds serving as the first President. He convinced the new body to hold the first Massachusetts Amateur at Myopia, which was played that September and won by Arthur Lockwood. That fall, in the November issue of Golf, an English writer commented as follows on intercollegiate matches held that summer between teams from England and the U.S.:

‘There is little doubt in the minds of the English players that the best course on which they played was that of the Myopia Hunt Club in Massachusetts. The reason why this course proved so popular was because it presented many of the characteristics of the British links. The holes are made to fit into the natural lie of the ground, and the ground is not tortured and twisted so as to afford holes of the supposed ideal lengths. Moreover, natural hazards are made use of and brought into play wherever possible, and the greens are not banked up and made true with a spirit level, but are left naturally rolling and undulating. All this is admirable, and it proves what a great advance has been made in the American conception of a great golf course.’

According to a Boston Globe article from September 25, 1904, Myopia was the only real test of golf in the area. “Massachusetts golfers do not get enough practice on first-class courses, and when they play the links at Myopia, they find the distances longer and the problems more complex than those to which they are used.” Even with the strong southwesterly wind, the writer felt the top Massachusetts players should have done better. The Boston Journal noted that the scores “prove conclusively that no player can average better than 40 strokes on a course of over 3,000 yards.” One can easily make the case that the writer was being a bit tough on the players.

In a practice round before the third U.S. Open at Myopia to be held on September 20 and 21 of 1905, three time champion Willie Anderson set a new course record of 72. His total was 314, 17 better than his 1901 score there, but still 7 higher than his winning score from the year before at Baltusrol. The members weren’t so thrilled with the tournament that year, commenting aloud about “the 300 cars and all that mob of people.” That fall the club hosted a quieter invitational tournament for the top amateurs with Walter Travis prevailing.

The next month in Country Life in America Mr. Travis wrote about the course at Myopia:

‘Laid out originally on the long side with reference to the gutta ball, it just happened, with the advent of the rubber-core ball, to meet every requirement of the modern game by simply adding hazards where experience suggested. As a whole, it is beyond criticism, no two holes are alike, there is not a single hole which is in any way unfair or which does not call for good play. The charm of the course lies in its diversity, the excellence of the lengths of each hole, the physical characteristics, the well-conceived system of hazards, good lies throughout, tees better than most putting greens, and putting greens, mostly undulating, which are the finest in the country, and equal to the best anywhere in the world.’

Even the soft white sand was considered noteworthy, coming as it did from Ipswich Beach.

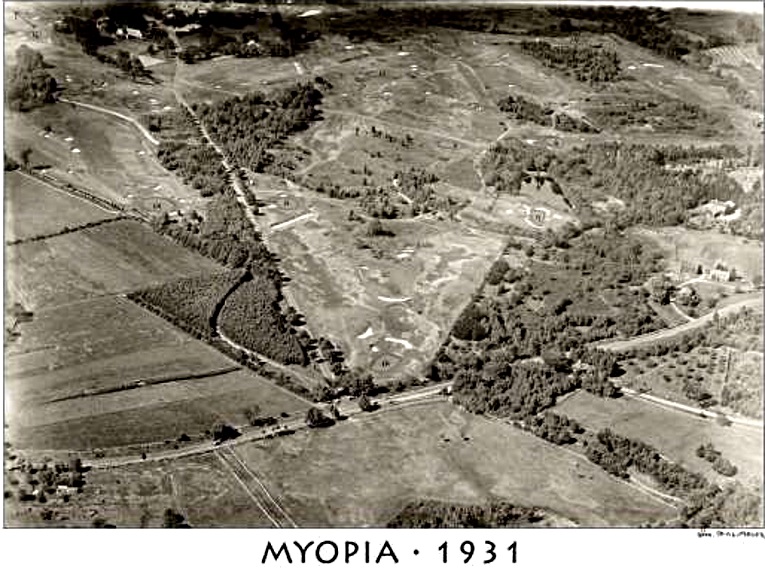

At Myopia today, it is not uncommon to see equestrians passing through the golf course and hear the baying of the hounds. History is omnipresent; on the walls are a number of colored plans and aerial photos which show the course’s evolution during the early part of the 20th century. To the well trained eye, the position of the 13th green has moved downhill and left from its original position adjacent to the second tee. The 1913 map below shows alternative locations for the current #13 green; ten years later they have merged, and the 1931 aerial shows a single green located where it remains today.

During the last several years, Myopia has undertaken a program of restoration associated with tree removal in an effort to bring back much of the historic golfscape that existed during the turn of the last century. Large stands on trees on the interior of the course have been removed in stages, and vistas not seen for many decades are now open. This reflects the conditions during the late 1800s where most of New England’s terrain was comprised of treeless expanses and rolling terrain, ideal for golf courses.

In addition, the club has, within today’s environmental constraints, attempted to restore how holes played many years ago. To that end, instead of moving the 13th green (and tee) back to their original locations (requiring a tee shot over the now hidden pond), a pair of large deciduous trees bordering the 12th green and 13th tee were removed and the 13th tee box was moved back and to the right. This allowed for the second shot to more closely resemble the original mid to long iron approach that was required before the era of 350 yard drives and 175 yard wedges.

Taken from the first green which offers players the first look across Myopia’s golfscape including holes 2 and 13 with portions of 4, 7 and 8 in the background.

Photo taken from today’s #2 Tee with #13 green at left and #9 green visible in the distance. This view has not been open since the 1930s.

The clubhouse veranda connects the main clubhouse and the locker room building. It offers a wonderful respite both before and after a round. The 18th green is visible in the background.

Taken from the 8th tee looking back towards the second green (flag) with the 13th green visible at far left and the 1st green at far right.

“Papa” Leeds, as he was then known, was appointed as Myopia’s Captain of the Green in 1907, a post he would hold until 1917. Leeds continued to tinker with Myopia for many years and was known to carry white chips and stakes to mark where the better drives landed. Often another bunker or hazard might appear in that area. He was doing this knowing that the best players in the world often played over those holes; not unlike the constant tinkering that goes on at many tournament venues today.

The last work attributed to Leeds was the 1913 expansion to 18 holes of the then 9-hole course at the Bass Rocks Golf Club, located in Glouster, MA.[1] During the last several years, Bass Rocks has undertaken considerable restoration work well beyond extensive tree removal. Numerous rock walls, ledges and mounding have been uncovered, and large stands of grasses fill out the rough and abut many hazards. The course has an old look and feel, along with the intact challenges (rocks and ledge) Leeds worked with when laying out 18 holes.

Looking back towards the clubhouse from behind the first green. Note the use of greenside mounding and considerable rocky terrain which requires a strong (and blind) first shot to give players a look at the green.

The green on the par 5 8th hole is set among rocks and sits on a knob that rejects all but the best played shots.

The 11th hole plays back towards the water through terrain typical to the golf course with areas of exposed ledge, mounding and well grassed rough.

The approach to the 12th green requires playing around and over mounds, exposed ledge, boulders and stone walls. It is typical of the kinds of terrain through which Leeds found and designed golf holes. Nothing of the sort is found on any of today’s modern courses. Some players are thankful, others enjoy the quirky aspect of early American golf.

The 15th hole is located on the original golfing grounds which were comprised of 6 holes. Today’s 15-18 play over that terrain, with Leeds having added bunkering.

The par 3 17th at 218 from the forward tees provides a considerable challenge given the sloping terrain that feeds into the deep greenside bunkers.

The iconic double lighthouse for which the club gets its name is visible beyond the stone walls which crisscross today’s holes 15-18.

During 1913, after Francis Ouimet’s U.S. Open victory in Brookline, Harry Vardon and Ted Ray again visited Myopia, along with Bernard Darwin, Britain’s counterpart in golfing prose to America’s Herbert Warren Wind. Darwin described the course as follows:

At some holes nature has done so well that not a single artificial hazard was needed, but as a rule she has been powerfully enforced by whole armies of bunkers, showing a strong predilection for getting just as near the flag as they possibly can. They are emphatically good bunkers, not only because they are cunningly placed, but they are good in themselves, workmanlike in shape, and yet with a certain serpentine grace, severe without being relentless.

C.B. Macdonald is often credited with introducing the concept of golf architecture to America through his use at National Golf Links of America of many features from the great golf holes found in the United Kingdom and elsewhere in Europe. Alexander Findlay was arguably the most prolific golf architect in America during the late 19th and early 20th century and many of today’s great clubs got their starts on his layouts.

Leeds, the only of the three to be born in America, designed and built equally challenging and interesting holes at Myopia well before NGLA was conceived, and before he had focused closely, during his 1902 visit, on the great links of the UK. If CBM is considered the father of American golf architecture and Mr. Findlay golf’s Johnny Appleseed; in this author’s opinion, Mr. Leeds is clearly the Papa of American golf architecture and deserves his place among the best.

Herbert Corey “Papa” Leeds died in Hamilton, MA on September 29, 1930 at the age of 76. His entry in the Harvard University Fiftieth Anniversary Class Report stating in its entirety “No special activities of interest.”[2]

August 7, 2016

All photos Kevin R. Mendik unless otherwise indicated.

[1] Since 1899, the order has been as follows with the original numbered holes in parenthesis: 1,2 (1), 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 (2), 9 (3), 10, 11 (4 played from a tee above the 9 green to today’s 11th green, although routed around the large oak between today’s 10 and 11 fairways), 12 (5), 13 (6), 14 (7), 15 (8), 16 (9).

[2] Weeks, Edward. Myopia, A Centennial Chronicle 1875-1975. (1975) Published at Hamilton, Massachusetts. Leeds remained at Myopia for many years, and was Captain of the Green from 1908-1917.

[1] See Harvard University Records of the Class of 1877, 25th, 40th and 50th Anniversary Reports.

[2] Obituary, Boston Evening Transcript, 29 September 1930.

[3] The Laws of Euchre as Adopted by the Somerset Club of Boston, March 1, 1888. ISBN 1245988557. The Laws of Bridge is referenced in Harvard University Records of the Class of 1877, 25th, 40th and 50th Anniversary Reports.

[4] Courtesy G.W. White Library at Mystic Seaport. http://library.mysticseaport.org/initiative/ImPage.cfm?BibID=36911&ChapterId=1

[5] Curtiss, Frederic H. and Heard, John. The Country Club 1882-1932 (1932).

[6] Bar Harbor Record, June 14, 1894. See also, Brechlin, Earl, Ed. The Spirit of Kebo The Kebo Valley Club 1888-1988.

[1] Lundberg, Dr. Robert N. Bass Rocks Golf Club 1896 1996 (1995). ISBN 0-9625660-3-9 See also online Club History at www.bassrocksgolfclub.org

[2] See fn.1

[1] See Labbance at page 127, referencing the Boston Daily Globe.

[2] Caner, George C. Jr. History of the Essex County Club 1893-1993. Manchester-by-the-Sea, Massachusetts Essex County Club: (1995) at pages 77 and 280. ISBN 0-9641777-0-6. See also Labbance, Bob with Siplo, Brian. The Vardon Invasion Harry’s Triumphant 1900 American Tour. Sports Media Group: Ann Arbor MI (2008) at page 133. ISBN 978-1-58276-294-4.

[3] Weeks, at p.48.

[4] Golf, USGA Bulletin November 1903.