The Dream Decision

by Tom MacWood

On July 14, 1931 at the Bon Air Vanderbilt in Augusta, Bob Jones addressed a group of reporters. Nine months removed from his historic Grand Slam, he announced the formation of the Augusta National Golf Club. He was bringing his ideal course to the South, ‘my ambition in connection with the Augusta enterprise,’ Jones said, ‘is to help build a course which may probably be recognized as one of the great courses of the world. I cannot deny that it is an idea very dear my heart, to see in reality a golf course embodying the finest holes of all the great courses on which I have played. But I am not having this dream alone, or without the most expert collaboration. Dr. MacKenzie is the man who will actually design the course.’ How did Jones arrive at Dr.Alister MacKenzie as the designer of his dream course? For the answer we must start ten years prior in the Kingdom of Fife.

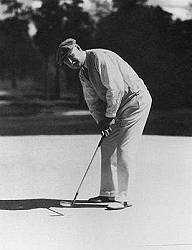

The 11th hole at St. Andrews is one of the most famous and imitated par-3s in the world of golf. Its christened name is High-coming home, but it is better known as Eden, for its green lies on the banks of the river of the same name. In the third round 1921 Open Championship Bobby Jones stood over a tap in on this very green when the seeds of Augusta National were planted.

Expectations were high as the ‘Boy Wonder’ entered his first Open Championship. After the first thirty-six holes on the Old Course, the young amateur found himself only five strokes from the lead. The wind was up the morning of the third round and unfortunately Bobby did not start well. He topped his tee shot on the first and took six. Two fives followed and the frustration was mounting. He was out in 46 and started the inward half with another six. His tee shot on 11 found the Hill bunker and eventually he laid five with a short putt for yet another six. You can almost see him looking out over the water as he muttered ‘what’s the use,’ he picked the ball up and placed in his pocket. Bobby Jones was 19.

Bobby Jones was the product of the American game. The typical American course provided no option as to where the tee shot should go, just avoid the bunkers and rough. The approaches were likewise straightforward. The tightly bunkered greens sloped from back to front and were normally well-watered, simply hit your approach high and it will land safely. The American game rewarded a ‘mechanical shot producer with little initiative and less judgement, and ability to only play the shot as prescribed.’

This first foray into British seaside golf had left him with what Bernard Darwin called a ‘puzzled hatred for the links.’ Links golf required the ability to think and improvise. ‘I shall never forget how I cursed Hoylake, and St.Andrews. At the time I regarded as an unpardonable crime, failure to keep the greens sodden, and considered a blind hole an outrage. I wanted every thing just right to pitch my iron shots to the hole. It was the only game I knew, so I blamed the course because I could not play it.’ The experience sparked a desire to unlock the secrets of the links game and the secrets of the Old Course in particular.

Over the next ten years Bob Jones studied links golf and its strategies, expanding his game in the process. His disgust for the Old Course and the seaside links had turned into admiration. The results were mind boggling, from 1923 to his retirement in 1930, he entered twenty-two major championships—winning 13 and runner-up in 4, he also compiled a Walker Cup record of 9-1. Included in this record were 4 championships in Great Britain in 5 attempts, including 2 victories at St. Andrews.

Although Bob Jones enjoyed unprecedented success on the golf course, the pressures of being on top were immense and he retired from championship golf following his Grand Slam of 1930, he was 28. It was time to rediscover the joys of golf and forming his own club presented him an opportunity to rekindle that spirit. And he was especially excited with the prospects of designing his dream course. The first step was to find an architect to help bring that dream to reality.

The twenties have been called the Golden Age of golf course design. This era produced more first class tests and great designers than almost all other eras combined. Under these circumstances Jones would have many choices of worthy golf architects, or would he. Charles Blair Macdonald, the father of American golf design, had been inactive for some years and his protégé Seth Raynor had died unexpectedly. A.W.Tillinghast was rendered inactive by the Depression. George Thomas had lost interest in golf course design. Hugh Alison was off to the greener pastures of Japan and his partner Harry Colt had not practiced in this country for nearly 30 years. William Flynn and Stanley Thompson were just starting to make a name for themselves. That left Jones with the choice of two men, Donald Ross or Alister MacKenzie.

The famous Scotsman

For many Donald Ross would seem to be the logical choice. He had redesigned Jones’s home course of East Lake in 1914. Many of Bobby’s Championships had been won on courses that Ross had designed or redesigned, including Scioto, Interlachen, Minikahda and Augusta Country Club. Jones had honeymooned at Biltmore Forest in Asheville, where he had sneaked out for quick round. He had for a time sold real estate for Whitfield Estates in Sarasota, a Ross design that Jones felt was ‘one of the best in America.’ He was also on a committee for the Atlanta Athletic Club that recommended Ross for the design Highlands Country Club, the same course in the Great Smokies where Jones would spend his summers and where he practiced before his 1930 run. Most importantly Ross had built both courses in Augusta—Augusta C.C. and Forest Hills were courses that Jones and his Augusta National founding partner, Clifford Roberts, had spent many an enjoyable winter round. Ross was without question the most famous and prolific golf architect in America, the problem was that Jones didn’t want an American course.

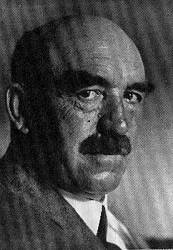

Alister MacKenzie, was born and raised in Yorkshire, England and followed his Scottish father into medicine after studies at Cambridge. On return from the Boer Wars in Africa, the lure of golf architecture became too great and he gave up medicine for design in 1907. He then entered into a very successful partnership with the great Harry Colt.

The other famous Scotsman

WW I interrupted that partnership, but it gave MacKenzie the opportunity to put into action what he had learned from the Boers on camouflage. He became the head of the British School of Camouflage and reportedly performed an exhibition for King George in Hyde Park exhibiting his theories of camouflage and trench building. Following the war MacKenzie wrote Golf Architecture, which reflected his philosophies on course design. Unfortunately prospects after the war had not been nearly as good as before it, so he decided to leave Great Britain and end his partnership with Colt. But not before spending a year studying and surveying the Old Course in detail, the resulting drawing is one the most famous in the world of golf.

After a tour of the United States and a brief but productive trip to Australia and New Zealand, MacKenzie settled in Northern California. In the two years following his move from the UK, he had designed or redesigned Royal Melbourne, Kingston Heath, Titirangi, Pebble Beach, The Meadow Club, The Valley Club, Cypress Point and Lahinch. With such a collection of spectacular successes, the good Doctor must have believed he had found the Midas touch.

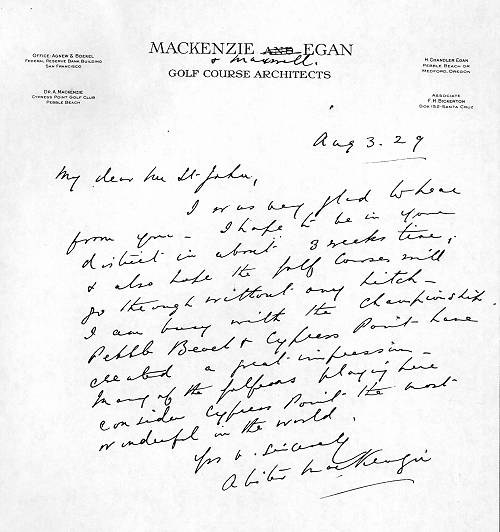

The story of Bob Jones and Dr. MacKenzie’s meeting has become lore. As the story goes Jones was playing in the first USGA event west of the Mississippi, the 1929 U.S. Amateur at Pebble Beach. The two time defending champ was heavily favored, but was upset in the first round by an unknown Johnny Goodman. After the early exit, Jones decided to stay and follow the Championship as an observer. The decision to stay gave him the opportunity to spend time with MacKenzie who had recently completed the spectacular Cypress Point and Pasatiempo, and the rest is history. As the tale goes, if it were not for Goodman, Augusta National would be a very different place.

But MacKenzie and Jones had met previously. MacKenzie was on hand at St.Andrews in 1921, 1926 and 1927 to watch Bobby compete. Following his victory in the 1927 Open Championship, MacKenzie had presented Jones an inscribed copy of his book Golf Architecture:

TO / Robert T. Jones (Jun)

The World’s finest

sportsman and greatest

Golfer–

With the author’s

compliments. A.D 1927

Because of the excitement surrounding the first major championship held in California, many of the competitors arrived early, some several weeks before. Jones was among those competitors who came early. The week prior to the Championship it is known the Jones, Cyril Tolley and Francis Ouimet enjoyed a round at Cypress Point in the company of Dr. MacKenzie (At the time MacKenzie was listing the club as his address, two years later he would move to Pasatiempo). The Amateur Championship was scheduled from September 2-7 and Jones had agreed to join Tolley, Glenna Collett and Marion Hollins the day following the final, September 8th in an exhibition to open Pasatiempo, the MacKenzie layout in nearby Santa Cruz. Who invited Jones to play is speculative—but it very well may have been MacKenzie. This prior commitment is the reason why Jones stayed on following his first round upset. So although the early loss may have given Jones the opportunity to spend more time with the Doctor, even if he had gone on to win the Championship, it would not have prevented Bobby from enjoying the bewildering charms of these two MacKenzie creations.

MacKenzie’s ability to easily befriend Jones, illustrates another distinction between he and Ross. ‘He was a moderately heavy cigarette smoker who always liked one before breakfast. He took a drink, preferably bourbon, whenever he felt like it, and, while I’ve seen him on special occasions indulge fairly liberally, he never lost control of his faculties,’ this was Clifford Robert’s description of Jones, but could have easily been of MacKenzie had scotch been substituted for bourbon. Jones and his drinking buddies O.B.Keeler, Grantland Rice, Roberts, among others could all drink a cocktail or two, and MacKenzie was equally famous for his own drinking prowess. ‘He was invariably entertaining, partly the result of a calculated effort on his part to reminisce a bit or tell a Scottish story. Then to, as often or not, he was hilariously amusing quite unintentionally.’ His ability to fit in with Jones’s inner circle is illustrated in the fact that during Jones’s historical feat in 1930, MacKenzie was present at three of his four victories, many times walking with Keeler, including his crowning glory at Merion.

Donald Ross like all good Scots enjoyed a drink also, as well as a cigar, but his image is more a fatherly one. As Charles Price, who lived in Pinehurst the last year the great mans life, pointed out ‘Ross was a strict man, with himself and everybody else.’ He was quite active at his church, although not a prude, he may have found it difficult to keep up with Jones and his drinking chums. Byron Nelson remembered him this way, ‘Ross was quiet–almost shy–and talked low and slow.’ Not a negative by itself, but when you consider they were trying to start a national club during the heart of the Depression, a more engaging promoter would be preferable.

Another important consideration was the ability of the chosen designer to collaborate, for this was going to be Bob Jones’s course based on his ideals. Surely the professional would be responsible for the design and construction, but with Jones’s input. Ross was a notorious solo artist, in fact of all the hundreds of courses he designed, there is record of only one dual effort–the Old Elm Club. There he is given credit with Harry Colt, but Colt was only there briefly to give limited advice and it was hardly a collaborative design. On the other hand, since leaving Great Britain, Dr.MacKenzie had become a specialist in working with others. Among those he worked with were former champions–Alex Russell, Chandler Egan and Marion Hollins, as well as author and social critic Robert Hunter and banker turned designer Perry Maxwell. The results of those collaborations included Royal Melbourne, Crystal Downs, Cypress Point and Pasatiempo, and surely would have been impressive to Jones.

One theory claims that Jones, who had a degree in engineering from Georgia Tech and a degree in English literature from Harvard, wanted someone who was his intellectual and educational equal. Ross had trained as a carpenter and had no formal education; MacKenzie was a physician and a graduate of Cambridge. But this was not an important consideration for Jones, after all Clifford Roberts was the man who Bobby gave the responsibility of administrating all aspects of the new club. Jones chose him because of his competency, not for his educational background. Roberts never finished the 9th grade.

Certainly personality and the ability to work in concert were important, but the paramount consideration was the ability design and construct a course that reflected Jones’s philosophies. After that first failure to contend with seaside golf, Jones had become an avid student of golf design. He felt that American courses were generally penal in nature, for they did not allow for options. There was one safe choice and the ball must be placed there. The result was an unthinking player who had the ability to play only one way. The British seaside links required strategy, the fairway were wide and the greens were firm and naturally undulating. The seaside course could ‘not be played without thinking. There is always some little favor of wind or terrain waiting for the man who has judgement enough to use it and there is a little feeling of triumph, a thrill that comes with the knowledge of having done a thing well when a puzzling hole has been conquered by something more than a mechanical skill.’

And for Bob Jones the epitome of seaside links golf was the Old Course at St.Andrews. ‘The more I studied the Old Course, the more I loved it, and the more I loved it, the more I studied it.’ Jones believed it to be the greatest course in the world and his goal was to produce a course that would attempt to replicate its virtues. ‘The main idea was to bring to inland Georgia the closest possible approximation to British seaside golf. It was intended to be an expression of my ideals in golf course design.’ He articulated those ideals as follows:

1. Give pleasure to the greatest possible number of players

2. Require strategic thought as well as skill

3. It must give the average player a chance, while requiring the utmost of the expert

4. All natural features must be preserved

These were all attributes found at the Old Course, the ancient links that Jones loved more than any other. The question was which architect would be most able to bring these ideals out in their design.

Donald Ross was born in Dornoch, Scotland. When he was 18, Ross had been encouraged to learn clubmaking. He moved to St.Andrews and worked at Forgan’s Golf Shop for one year and then on to Carnoustie for an additional year. He then returned to Dornoch to become pro and greenskeeper. Golf architecture historian Ron Whitten says, ‘what little he knew of course architecture before coming to America he picked up from working at Dornoch.’ Believing there was great opportunities abroad, Ross decided to come to America in 1899. He started at Oakley Country Club as club professional and at the same time building them a new 18-hole course. He then moved on to Pinehurst in the same capacity and soon his design career would take off.

Although born in Scotland, Ross never practiced golf architecture in his native land. His early designs were quite crude and it wasn’t until a tour of the British Isles in the summer of 1910, when he made a study of the great courses of his homeland, that he became a serious golf architect. Upon his return his designs were more polished and sophisticated—they had a natural appearance that was lacking in his earlier work.

As far as his philosophies on design are concerned, he is normally identified with the strategic school of design, but that maybe a mischaracterization. Ross loved bunkers and used them liberally. Robert Trent Jones who revised many of his layouts wrote, ‘the courses Ross built during the 1920s, it wouldn’t be uncommon to find 200 to 220 bunkers on a single course.’ Seminole, his great design of 1929, had 189 bunkers. If anything Ross leaned more toward the penal school through most of his career, he wrote ‘perhaps the best evidence of the modern development of the game are the changes which have made our course more severe and therefore better tests, for golf is not golf when poor play is not penalized.’

MacKenzie on the other hand was allied with the strategic school. As an admirer of the Old Course, he believed that hazards should ‘be placed with an object in mind, and not one should be made which has not some influence on the line of play to the hole.’ He believed that when a player confronts a hazard two things are essential, there must be a alternative route for those unwilling to take the risk and there must be a definite advantage gained when the hazard is carried successfully. Not that he was opposed to using sand, Cypress Point and Royal Melbourne are covered with beautifully sprawling bunkers that the Doctor was famous for. There were those who thought he was talking out of both sides of his mouth and that his courses had a wealth of penal side bunkers, to which he replied ‘the only one that has is Cypress Point and these are all natural sand dunes made by another fellow, not myself.’

Not only was MacKenzie conversant with links golf and its strategies, he had also designed and built several seaside layouts, including Troon Portland, Littlestone, Seaton Carew and Lahinch. And when it came to familiarity with the Old Course, MacKenzie’s advantage was clear. He had been hired by the R&A to make a map of the links. ‘It took me a full year to complete the task, notwithstanding the fact I thought I knew the course thoroughly. In actual fact I found my knowledge was of the slightest, and the subtleties which I discovered have always been a source of amazement to me.’ Ironically Jones had a copy of the drawing and studied it before his victories at the Old Course in 1927 and 1930. After which it hung in his law office for many years.

After the Depression, when jobs were difficult to come by and economy of construction was key, MacKenzie adjusted his style. Two courses that reflected this change were the Jockey Club in Buenos Aires and Bayside outside New York City. The Jockey Club was designed early in 1930 and was on dead flat land. MacKenzie created numerous swales and mounds that were designed to reflect the natural formations near the sea. Asked by the club about bunkers he said the undulations were sufficient and there was no need for sand, although he later capitulated. Bayside was on similarly dead flat land. Here the Doctor created undulating fairways, huge greens, some 40 yards in width, broken by ridges and mounds. It was said to be reminiscent of a Scottish links. Bayside was also devoid of rough and featured only 19 bunkers, which were used with knolls to influence the line of play–a foreshadow of what was to come. MacKenzie said of the layout just before completing it, ‘this course will take a lot of understanding.’

Finally if you analyze the four principals that Bob Jones wanted for his ideal course, you will find that each is discussed in MacKenzie’s book Golf Architecture. This is what he wrote:

1. The successful negotiation of difficulties is a source of pleasure to all classes of players.

2. In the old view of golf, there is no main thoroughfare to the hole: the player had use his own judgement without the aide of guide posts, or other adventitious means of finding his way. St.Andrews still retains the old traditions of golf.

3. A course should not only be a good test of golf, but also a source of pleasure to all classes of players.

4. I have endeavored to conserve existing natural features, and where these are lacking to create formations in the spirit of nature herself.

It would appear that Bob Jones was greatly influenced by MacKenzie’s philosophies.

If Bob Jones had chosen Donald Ross to build his ideal course, I don’t think it would have been a surprise to anyone. After all he was the most famous designer of the day and rightfully so. But Jones chose MacKenzie and after considering all the factors, he really had no choice. What was not generally known was the degree to which MacKenzie had influenced Jones’s ideas on golf course design. That influence and their mutual love for the Old Course made Jones’s decision an easy one. ‘It happened that both of us were extravagant admirers of the Old Course of St. Andrews and we both desired as much as possible to simulate seaside conditions insofar as the differences in turf and terrain would allow.’

If Bob Jones had chosen Donald Ross to build his ideal course, I don’t think it would have been a surprise to anyone. After all he was the most famous designer of the day and rightfully so. But Jones chose MacKenzie and after considering all the factors, he really had no choice. What was not generally known was the degree to which MacKenzie had influenced Jones’s ideas on golf course design. That influence and their mutual love for the Old Course made Jones’s decision an easy one. ‘It happened that both of us were extravagant admirers of the Old Course of St. Andrews and we both desired as much as possible to simulate seaside conditions insofar as the differences in turf and terrain would allow.’

Following the choice of MacKenzie, legend has it Ross was so disappointed that he dedicated himself into making Pinehurst #2 in to the greatest course in the South. The fact that Jones was planning to build his dream course was not public knowledge, so it is difficult to believe that he could be too disappointed about something he had no knowledge of. And even if he was mildly upset by the snub and it was his inspiration for revamping #2 in 1935, golf is richer for it. The result was a course not dissimilar to Augusta National–spacious fairways, large undulating greens and a scarcity of bunkers–a monument to Ross’s strategic genius.

That day in July when Jones formally announced his decision to build his dream course, MacKenzie was present. Later that day, he and the good Doctor ventured out to the site. It was MacKenzie’s first chance to view what Herbert Warren Wind calls ‘the prettiest vista in golf.’ One can almost imagine the two of them, Jones without his suit jacket and MacKenzie carrying a topo map, excitedly wandering out over the property. Walking up and down the hills, exploring the network of streams, they are constantly trading ideas back and forth. When they reach a gentle valley and the Doctor turns to Jones and says, ‘this is where we will build our version of Eden.’ Instantly transported to another day, Bobby silently nods.

The End