Timeless Golf

at

Quogue Field Club

By Benjamin S. Litman

September 2015

A view out over the aptly named “Marshes” hole at Quogue Field Club, with a distinctive orange flag punctuating the horizon.

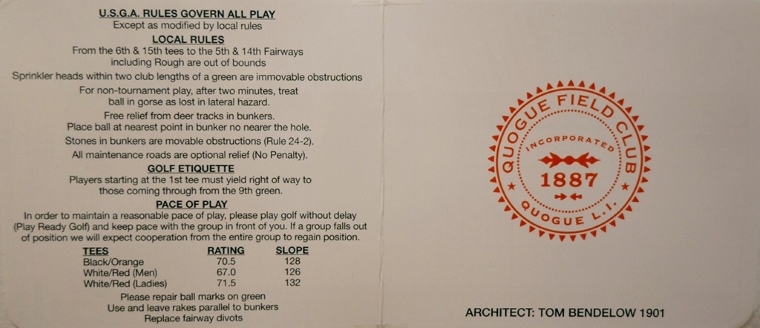

Situated in the heart of “The Quiet Hampton,” Quogue Field Club (QFC) offers nine holes on superior flat golfing terrain. The course—initially attributed (at least on the Internet) to James Hepburn and R.B. Wilson in 1887, but now attributed (by the club itself) to Tom Bendelow in 1901—is one of the oldest in the United States. Like the Village of Quogue itself, QFC is part of the Town of Southampton and located immediately to the east of Seth Raynor’s Westhampton Country Club. Unlike the more tony Hamptons, Quogue and Westhampton benefit from their proximity to New York City—generally a 90-minute trip by car, with convenient train and bus options not much longer. For those more familiar with the better-known courses of the area, Quogue is equidistant—and only 15 miles—from Friar’s Head (to the north) and Shinnecock Hills, National Golf Links of America, and Sebonack (to the east).

QFC’s par-3 4th offers what might be a one-of-a-kind green in the world of golf: a titled Biarritz with Redan-like playing properties. Two large mounds on the right side of the green (here, viewed from behind) are responsible for both its right-to-left tilt and its two distinct tiers. Tempting though it is to attribute the green to Wilson (his predecessor at Shinnecock Hills, Willie Dunn, Jr., did design the original Biarritz in the late 1880s in France, after all), the current design is a modern creation.

Unlike in my other photo tours on the Discussion Group, I am including a bit of history here both because it interests me and because QFC, based on my extensive searching, is at once a source of intrigue and a mystery to all but a select few GCAers. In his profile of Westhampton Country Club, Ran notes that “[w]ith so many world-renowned courses of historic importance, it is a tough neighborhood indeed for a course to gain its fair share of recognition.” That is even truer in the case of Quogue, whose very existence as a village, to say nothing of its golf course, is unknown to many.

Chester Murray, a member at QFC and Co-Chair of the Quogue Historical Society’s Board of Directors, is in the process of writing, in book form, an illustrated history of golf at the club. The brief history I set forth here reflects my best efforts based on publicly available information, almost all from online sources.

QFC might be flat, but it hardly lacks for excitement; here, the natural grasses and low-profile bunkering around the 8th green.

A Brief History of the Golf Course at Quogue Field Club

Quogue—originally, “Quawquannantucke” or “Quaquanantuck,” the latter being the current name of the 8th hole—dates to 1659, when an English colonist named John Ogden purchased the land from the Shinnecock tribe of Native Americans. Sometimes referred to as the “Second Purchase,” Ogden’s Quogue Purchase was the second largest of Native American land on Long Island, trailing only Southampton, to which Quogue was eventually sold. Since its emergence as a summer resort village in the 1890s, Quogue has remained a haven for those who want the natural beauty of the “East End” of Long Island without the glitz and glamour that have come to define the Hamptons experience. The result is a village with precious few commercial establishments but enough charm to fill a metropolis. As the village’s website proclaims, “Quogue proudly stands apart from the ‘Hamptons Scene’ focusing, as it always has, on wholesome family oriented activities.”

Architecturally, the history of the Field Club’s golf course is not straightforward—and that’s without accounting for the loss of nine holes after the great hurricane of 1938. Conventional wisdom holds that Quogue originally had 18 holes and that its present nine-hole configuration represents the leftovers from the hurricane. Not so. According to an illuminating Ian Andrew post in Sven Nilsen’s 2014 “Breaking Down the Bendelow List” thread, the Suffolk County News reported at the time Bendelow’s course opened in 1901 that “it is a nine hole course.” That suggests that the other nine holes were built sometime after the opening and before the 1938 hurricane.

The bunkering at Quogue, here guarding the right side of the home green, calls to mind other classic early American golf courses, such as Garden City. Note the bike rack, immediately inside the club’s entrance, next to the first tee off on the right—a clear reminder that QFC is a neighborhood club.

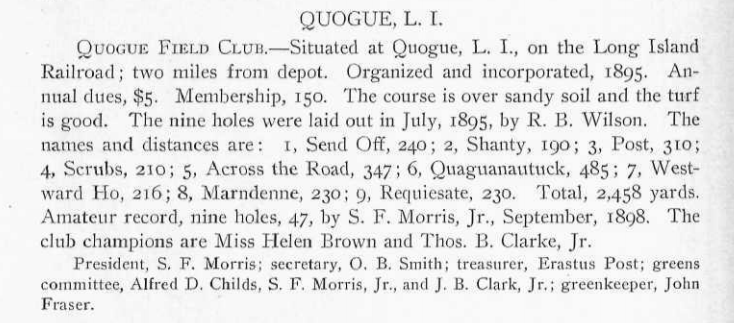

According to the Quogue Historical Society, moreover, the original nine holes were designed by Wilson, not Bendelow, but were open for play only from 1896 to 1900—and on a different, smaller plot of land several blocks to the west of the current course and farther from the bay and ocean. The 1896 opening date of the original Wilson design makes Quogue the third-oldest golf course in the Hamptons, behind Shinnecock Hills (1891) and Maidstone (1894). In June 1897, the USGA elected Quogue as an “allied member” of the association. Little information about the original Wilson nine is publicly available, but we know the hole names and lengths from an 1899 edition of the Official Golf Guide, which cites July 1895 as the date Wilson laid out the course:

“Requiesate,” the name of the original closing hole at Quogue, appears to be a misspelling of either the plural imperative or the hortatory subjunctive of the Latin word “requiescere,” typically translated as “rest,” but also as “quiet down” and “end.”

After the 1900 season, Bendelow was brought in to build a replacement nine, which opened on the current site in 1901, a year after the clubhouse had been moved to the same location in anticipation. Interestingly, the Bendelow hire almost didn’t happen, as the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported on August 27, 1900 that “[t]he course of the Quogue Field Club at Quogue, L.I., is to be increased to eighteen holes by John Dunn [nephew of Willie Dunn, Jr.] at an early date.” But within two months, the club apparently had settled on Bendelow instead of Dunn—and a new, replacement nine instead of a new, additional nine—as the same newspaper reported on October 18, 1900, in an excerpt posted by Sven Nilsen last year, that “[w]ork on the new golf links at Quogue, L.I., is progressing rapidly, and the greens are being prepared for next season” and “[t]he course was laid out by Bendelow.” Citing a 1902 photograph from the Quogue Historical Society, Phil Carlucci reports in his 2015 book Long Island Golf that a little-known man named Otto Kammerer was QFC’s first golf professional.

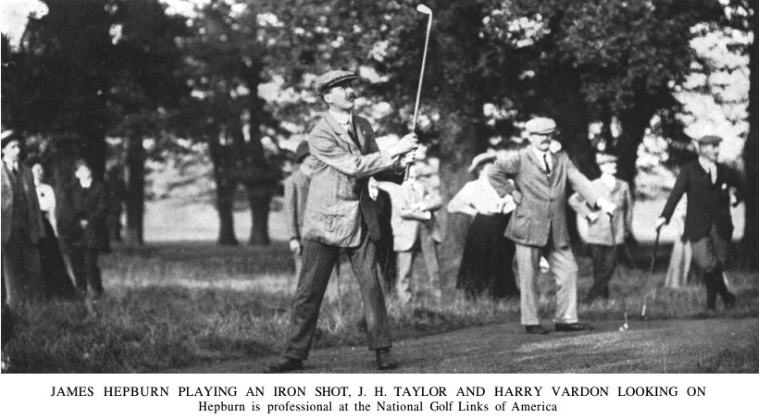

According to Mr. Murray, the expansion from Bendelow’s nine to a full 18 took place after the 1921 season, when “[t]he new nine holes were designed by James Hepburn.” That description accompanies a recent painting by Mark Ruddy, whom Mr. Murray “commissioned to paint the golf course as it appeared just before the 1938 Hurricane.” As Ruddy’s painting reflects, Hepburn’s nine included a heavily bunkered Redan, two other par-3s along the water, a short par-4 Valley hole, and back-to-back par-4s, including a short Plateau hole, with diagonal water carries off the tee. Given that Hepburn was the professional at National Golf Links of America at the time, one wonders how much Macdonald’s work there influenced him in designing his own nine holes at Quogue. Those holes opened for play on July 29, 1922, according to the County Review, one month before National hosted the inaugural Walker Cup 15 miles away.

“Quogue Field Club 1938,” by Mark Ruddy (Courtesy of Chester Murray). Although the numbering of the Bendelow nine (the front in Ruddy’s painting) changed a few times after the Hepburn nine opened for play in 1922, Bendelow’s routing has remained largely the same, the sequencing has not changed at all, and the numbering has reverted to the original. In 1901, as now, the 1st hole (the 7th in Ruddy’s painting) left from the clubhouse, while the 9th hole (the 6th in Ruddy’s painting) returned to it.

In preparation for the 1927 season, “many improvements on the club’s eighteen-hole golf course [were] effected, following the plans of Captain C. H. C. Tippet, noted [English] golf architect,” according to the weekly magazine Brooklyn Life and Activities of Long Island Society. That same summer—when Tippet’s original 18-hole layout at Montauk Downs also opened for play some 45 miles to the east—the New York Times reported that Phillips Finlay, a decorated, long-hitting 19-year-old amateur and Harvard freshman, shot 67 (34-33) to set a new course record on the 18-hole QFC layout. Finlay, who also won several club championships at QFC, eclipsed the record previously held by an assistant professional at Westhampton. Three years later, in 1930, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle lauded QFC with the headline “An Excellent Example” in light of the club’s decision to “adopt an idea which conservationists have repeatedly urged upon country clubs”—namely, to designate its land a “sanctuary” for wildlife.

In 1928, a year after setting the course record at Quogue, Phillips Finlay—having been “out-driven, out-pitched and out-putted with monotonous regularity,” according to the Associated Press—lost 13 and 12 to Bobby Jones in the semifinals of the 32nd U.S. Amateur, which Jones went on to win (Credit: Library of Congress).

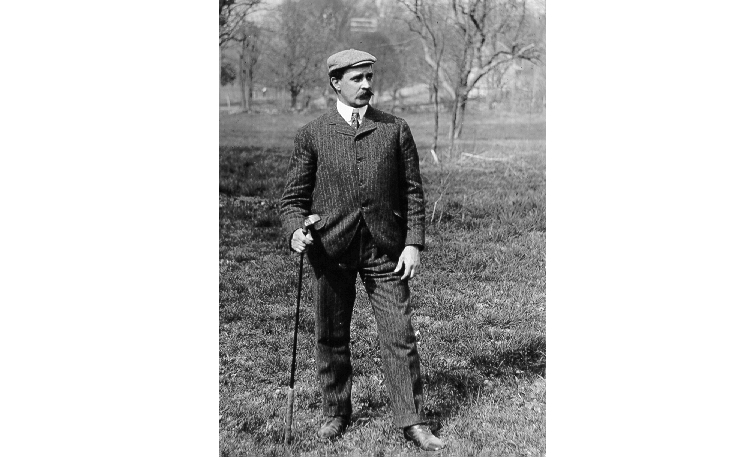

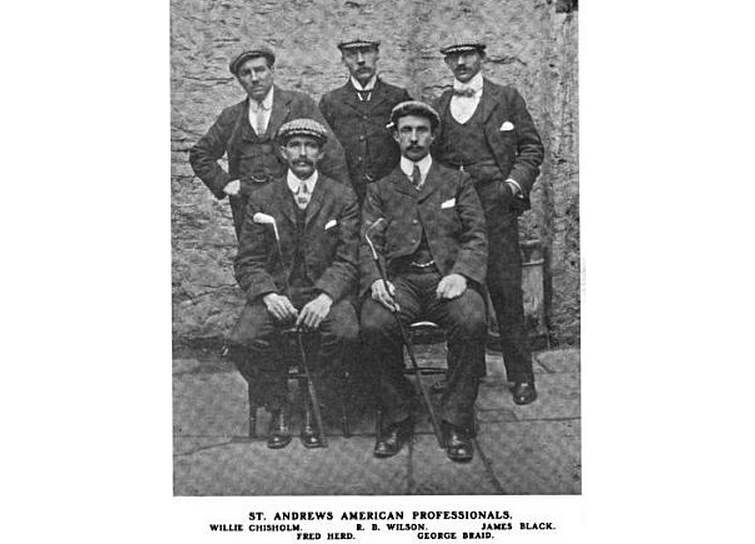

Much has been written about the prolific Bendelow, but what do we know about Wilson and Hepburn? Both were accomplished players, clubmakers, and leaders in the game—and Scottish. Robert Black (“R.B.” or “Buff”) Wilson was born in Anstruther and learned clubmaking in St. Andrews as an apprentice to Old Tom Morris in the 1880s. In 1888, Wilson became the professional and greenkeeper at Minchinhampton Golf Club in Gloucestershire, where he also designed the club’s acclaimed Old Course. Following stints as the professional at three other English clubs, Wilson journeyed to America in 1895 to succeed Willie Dunn, Jr. as the professional at Shinnecock Hills, where Wilson would place ninth, besting his predecessor by three strokes, in the following year’s U.S. Open. An 1898 Outing article, entitled “Golf and the American Girl,” called Wilson “one of the best players with the iron clubs ever seen in this country” and credited him with converting the legendary Beatrix Hoyt’s “natural gift to a finished game.” Hoyt, who had “the most beautiful follow-through to be imagined” and “simply superb” nerve, won the second U.S. Women’s Amateur in 1896 at the age of 16 (as well as the third and fourth the next two years, before retiring from the game at 20), and held the record for youngest female USGA champion until 1971, when Laura Baugh broke it.

Wilson, at back middle, was a well-known clubmaker in St. Andrews before coming to America. After serving as the head professional at Shinnecock Hills, he moved on to the Hartford Club in Connecticut (Credit: Golf Illustrated).

James P. Hepburn, meanwhile, was the secretary of the PGA of Britain for 12 years before Charles Blair Macdonald recruited him to come to America in 1915 to serve as the professional at National Golf Links of America. In his “Our Foreign Letter” dispatch from early that year, Bernard Darwin warned Americans of “the invading army that is soon setting out from our shores to yours” for exhibition matches and that summer’s U.S. Open at Baltusrol. Among the “invaders” was Hepburn, whom Darwin described as “a thoroughly good player,” one “who has for years been hovering on the edge of the very first rank that the Triumvirate and one or two more have so wonderfully kept to themselves.” Once in America, Hepburn not only set the course record at National (a 35-34 69 in 1916), but quickly became the chair of the committee charged with drafting a constitution and bylaws for the PGA of America. He also had stints, during winters, as the professional at Macdonald’s and Raynor’s Mid Ocean Club in Bermuda. Apart from designing the nine additional holes at Quogue after the 1921 season, Hepburn also served as the club’s professional during the 1933 season, according to the June 3 edition of the County Review from that year.

Born in Carnoustie, Hepburn had “many pleasant struggles” with Bernard Darwin when Hepburn was the professional at Royston Golf Club and Darwin was an undergraduate at nearby Cambridge (Credit: Golf Illustrated).

To recap, Wilson designed the original nine-hole course at Quogue in the summer of 1895, but that course, which opened for play a year later, yielded to a new Bendelow nine, on a different plot of land, after being open for only four years. Bendelow’s course opened for play in 1901. Hepburn designed the also-defunct second nine after the 1921 season, with play opening on them the following summer, and Tippet made “many improvements” to the 18-hole layout between the 1926 and 1927 seasons. Hepburn’s nine unfortunately fell victim to the 1938 hurricane, although not for the reasons (e.g., flooding) traditionally cited. According to Mr. Murray, the hurricane destroyed the village’s two bridges to the beach. A new single bridge required the extension of a street—Post Lane—directly through the Hepburn nine. As the Mid-Island Mail reported on December 21, 1938, “[t]he proposed approaches involve a right-of-way through the Quogue Field [C]lub’s golf course, and this displeases some.” Unfortunately, Mr. Murray notes, “[t]he Club made a valiant, but ultimately not very successful, effort to restructure the holes around the extended Post Lane and new bridge.” By “reciprocal arrangement,” QFC members played their golf at Westhampton Country Club in the summer of 1942, according to the New York Times. Thereafter, according to Mr. Murray, QFC closed down entirely until 1945, owing to World War II “and the steady decline of active Club membership.” When it reopened, it did so only on Bendelow’s nine, where it has remained—albeit with modifications by several architects, including Frank Duane, Stephen Kay, and, most recently, Ian Andrew—ever since.

The punchbowl green at QFC’s 2nd, surrounded by moat bunkering on all sides, was among the first of its kind in the United States.

The date once attributed to the supposed Hepburn and Wilson design, 1887, doesn’t square with several facts, including that Wilson and Hepburn didn’t come to this country until 1895 and 1915, respectively. Bendelow, originally from Aberdeen, Scotland, arrived earlier, in 1892. It is the club’s incorporation, rather than its course, that dates to 1887. Together with the above-cited October 18, 1900 pre-opening article in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle—which described a “very attractive” course with “a number of natural hazards”—the August 10, 1901 post-opening edition of the Brooklyn Life confirms that Bendelow is now properly considered the architect of record, noting both the relocation of the clubhouse and “a fine golf course laid out by Bendelow—starting from the front and winding in the direction of the ocean, and then to the shores of Shinnecock Bay and back to the club, with bunkers and water hazards second to none anywhere on that part of the island.”

The architect’s evident respect for the land—very little is built up from, or onto, the flat field on which QFC sits—reflects Bendelow’s “naturalist” philosophy of golf-course design. As his grandson Stuart, whom Ran interviewed in 2002 (https://golfclubatlas.com/feature-interview/stuart-bendelow-september-2002/), explained, “I don’t think he was a strong proponent of reshaping the countryside to make a golf course. Using the natural setting made for the best result and the least expense. His goal was to give the best possible golf layout he could within the client’s budget. This often meant doing without extensive ground movement, water hazards, heavy trapping or other features costly to build and maintain.”

Consistent with Bendelow’s hands-off design philosophy, the water hazards at Quogue—like this inlet from the bay running between the 5th and 6th holes—are found, not built. The Atlantic Ocean lies just beyond the homes in the distance.

Given that Bendelow’s nine opened in 1901, QFC would have been one of his early designs; Stuart’s remark that his grandfather’s “early courses were very simple, in design and in construction,” strongly suggests that it was. If so, Bendelow likely spent little time at Quogue. As Stuart explains, his grandfather’s “time at these [early] courses was relatively short. Following the staking of the course and instructions to whoever was going to be responsible for construction, he moved on to the next job.” Bendelow’s rapid-fire approach to course construction, Stuart notes, “is what made him the ‘Johnny Appleseed’ of American golf.”

Now 114 years later, Quogue remains a simple, flat affair where the hands of the architect become apparent only when the golfer reaches the greens and surrounds. Do not mistake simplicity and flatness for blandness. I find flat courses in general to be underrated, if not ignored. Playing golf on a wide-open, flat field distills the game to its essence and conveys a certain timelessness. Not insignificantly, the 1st and 18th holes on the Old Course at St. Andrews rest on precisely such land. The starting and finishing holes at Quogue bear more than a passing resemblance to those at the “Home of Golf,” as well as those in North Berwick—and pay homage to that tradition. After all, whether it was Bendelow, Hepburn, Wilson, or some combination thereof, it was the Scots who designed Quogue.

Evocative of some of the great links of the world, Quogue’s first and final holes leave from and return to the clubhouse along the same piece of flat land.

Quogue provides ample width off the tee to satisfy the average player and enough intrigue on and around the greens to challenge the expert player, timeless qualities in golf-course architecture. “One word frequently used in [my grandfather’s] writings on golf courses is ‘sporty,’” Stuart notes. “I think he meant by this that it should present an enjoyable play for both beginner and advanced player; not too hard to discourage the new player and not without challenge to the more accomplished golfer.”

From bikes, to cars, to boats (here, along Quogue Canal behind the 5th green), golf at QFC is an immersive, interactive experience with the village and its inhabitants.

Though QFC has nine holes for golf, members often play 18 from two sets of tees: the first loop from the black tees and the second from the orange tees, reflective of QFC’s flags, which are orange with black writing. The current scorecard not only lists all 18 holes separately, but assigns different names to each. That detail might feel a bit forced; apart from length and angles, the holes play very similarly on the “front” and “back” nines. But the legend in the upper-left corner of Mark Ruddy’s painting confirms my suspicion that, instead, many of the “back nine” names were once those of the nine Hepburn holes lost after the 1938 hurricane—in which case maintaining two names for each current hole is a most fitting tribute indeed. The legend also reveals that some of the current names are homages to the original Wilson nine (e.g., “Quaquanantuck”) or altogether new (e.g., “Clubhouse,” “Hedges,” and “Long”), while some of the original back-nine names (e.g., “Redan,” “Valley,” “The Pond,” and “Plateau”) have not been retained.

Quogue has tremendous variety in its nine holes: two par-3s, both of which carry architectural significance (a punchbowl at the 2nd and a hybrid Biarritz/Redan at the 4th); a nice mix of short, potentially drivable par-4s (at the 3rd and 6th) and long par-4s (at the 5th and 7th); and two par-5s, which bookend the round and run parallel to each other departing from, and returning to, the clubhouse. Notably, the yardage of the Bendelow nine has barely changed over time—and is actually shorter now (3,252 yards, taking the longest of each hole’s front- and back-nine yardages) than it was in 1938, when it stretched to 3,279 yards.

Above all, QFC is blessed with naturally firm, bouncy turf that allows for the ground game—and begs for it when the winds kick up on this exposed landscape only a few hundred yards from the Atlantic Ocean. As another 1898 Outing article put it during the era of Wilson’s nine, QFC “shar[ed] with Shinnecock Hills in the boon of a thin sandy turf” ideal for golf. That was necessarily even truer in 1901, as it is today, as Bendelow’s nine opened on a different plot of land closer to the bay and ocean. The greens are accordingly kept like on the links of Great Britain: pure, but just grassy enough to allow all players to try to make putts without too much fear of the consequences of missing. QFC’s flatness, moreover, lends suspense to almost every hole, as hazards are barely visible from the tee. The sum of these parts makes Quogue a nine-hole course worthy of further consideration.

The evening light draped over the 1st green has a particularly calming effect at wide-open Quogue, which remains “one of the finest on Long Island” and “one of picturesque beauty,” as the Suffolk County News described the course when it opened in 1901.

Ian Andrew has led a restoration over the last few years, which has seen the removal of interior trees at QFC that influenced play. This was especially true for those trees that separated the adjacent 1st and 9th holes, where bunkers and mounds now serve the same purpose. Views have opened up, and the course’s trademark flatness is now widely apparent, though detractors could say that some of the course’s modern-era “definition” has been lost.

Among the longest “through” views opened up by recent tree removal at QFC is this one from the 1st green across the 8th and 4th greens and the 5th fairway beyond, as well as the 6th green in the background on the far left. On reaching the 1st green (in the foreground), the golfer encounters a repeating feature of Bendelow’s design: bunker complexes consisting of multiple, small, geometrically shaped hazards in close proximity to the green edges and surrounds.

Although less long, this new “through” view from the 1st fairway out over the 9th fairway, 8th tee, and 7th green highlights the intimacy of Bendelow’s routing. Note the pushed-up back and moat bunkering, also typical of many of the greens at Quogue.

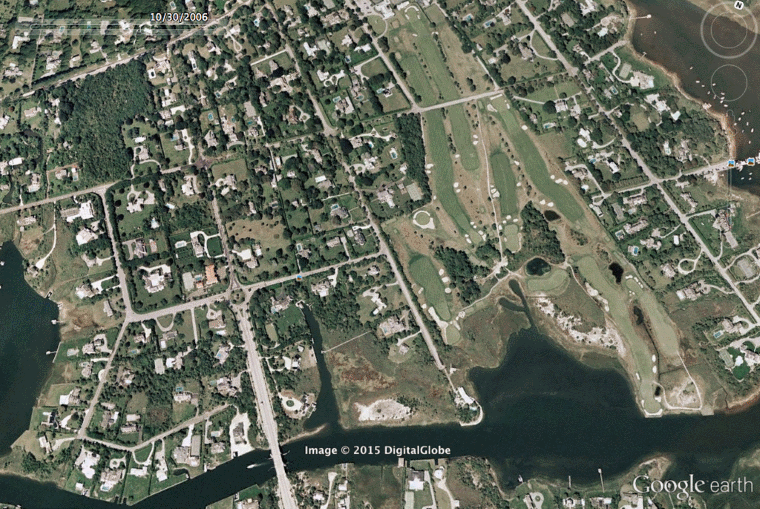

A series of aerials—one, thanks to Jim Sullivan, taken by the U.S. Army three months before the 1938 hurricane; another from Google Earth in 2006; and a final one taken by a professional photographer earlier this year—offer a fascinating look at QFC’s progression over time. Apparent in each of the aerials are the abundant open-front greens and the geometric appearance of the heavily bunkered green complexes.

A June 1938 aerial of QFC (Credit: U.S. Army Air Corps). The nine Hepburn holes to the left of Ocean Avenue (at left center/bottom) were those lost/abandoned, like the Ocean Avenue bridge itself, after the September 1938 hurricane. Of the remaining/current Bendelow nine to the right of Ocean Avenue, note that the 4th hole (at right center, the hole perpendicular to all the others on that side) was not the bunkerless Biarritz/Redan par-3 that it is today.

A 2006 aerial of QFC. Where the Hepburn-designed back nine once sat, homes—and the extended Post Lane—now do. Note the visible swale (the dark-green patch in the middle of the green) in the Biarritz/Redan 4th. Apart from the changes to that hole and the 6th (where two bunkers once guarded the end of the fairway), Bendelow’s original design remains remarkably intact more than a century later.

A close-up May 2015 aerial of QFC (Credit: Vincent T. Vuoto/BestAerialPhotos). Note the Church Pews along the left of the 3rd fairway and the extended scar bunker intruding into the fairway from the right. According to Google Earth, the Church Pews were added in the 2007-2008 timeframe. Note also the renewed absence of interior trees, especially between the 1st and 9th holes (top center) and 7th and 8th holes (middle right)—a credit to the recent Ian Andrew-led restoration. In the foreground are the 5th green and 6th tee, the closest the golfer gets to the bay and ocean at QFC.

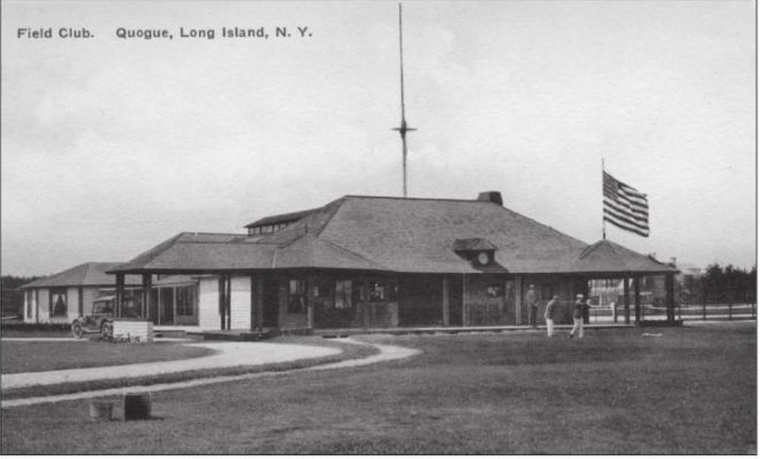

After having been moved in 1900 from its old location on Jessup Avenue, the QFC clubhouse has remained at the new Club Lane location ever since. But the club did raze the original structure in 2012, building in the same spot a wholly new structure that opened the following year. While retaining the low-profile nature and basic structure of its predecessor, the current clubhouse has a shingled facade characteristic of many homes in Quogue and throughout the Hamptons.

The original QFC clubhouse, after having been moved to its current location in advance of the 1901 season. At right, a golfer plays off the original and current first tee of Bendelow’s nine-hole course (Credit: Quogue Historical Society).

Immediately before it was demolished in September 2012, the original clubhouse looked very much as it had more than 100 years earlier (Credit: Neil Salvaggio).

The current QFC clubhouse retains the orientation and basic structure, if not the facade, of the original.

While more subtle than the Himalayas at St. Andrews or the Punchbowl at Bandon Dunes, QFC’s practice putting green, with the club’s flagpole at its center, has 18 holes with correspondingly labeled iron flag sticks.

A Hole-by-Hole Tour of the Golf Course at Quogue Field Club

Hole 1 (“Fairview”): 528 yards, par 5 / Hole 10 (“Clubhouse”): 492 yards, par 5

Playing straight away from the clubhouse and into a prevailing wind coming from Shinnecock Bay and the Atlantic Ocean beyond, this par-5 is a “par bonus birdie” hole. (By contrast, the adjacent 9th, which runs downwind in the opposite direction, is a birdie hole.)

QFC’s flatness is unmistakable from the first tee, which offers views over almost the entire course and, late in the day, of the rising moon.

Where trees used to separate the 1st fairway (to the right) and the 9th fairway (to the left), bunkers now sit. Here, a dual-sided bunker encountered after crossing Quaquanantuck Road, which bisects the adjacent fairways and allows passersby to gaze upon the course. The dark stand of trees on the right is out of bounds, which lines the first 350 yards of Quogue’s opener. Although the playing corridors and green open up from the right side, the out of bounds makes it a risky target from the tee.

When the green first comes into view after a slight left turn in the fairway, the golfer encounters a feature that repeats throughout the course: an open-front green, at grade, with “squared up” elements that allow for low, wind-skirting, run-up shots—a regular necessity on a course as exposed to the wind as Quogue. These inviting features, together with the pushed-up backs, evoke comparisons to the greens built around the same time by Bendelow’s contemporary and fellow Scot Donald Ross.

As the golfer walks to the 2nd tee, the view back to the 1st green reveals yet another feature integral to the design at QFC: pushed-up high points at the back of otherwise low-profile greens. Unlike the other holes where this feature repeats, the area behind the pushed-up back of the 1st green is bunkerless, requiring a delicate pitch off of tight grass, or wispy rough, to a green running away. Note the green mailbox; it contains extra scorecards for those who forgot to take one before teeing off.

Hole 2 (“Punchbowl”): 148 yards, par 3 / Hole 11 (“Hedges”): 161 yards, par 3

Quogue’s first par-3 features what might be the first of its kind in the United States: a punchbowl green. Raynor’s nearby Westhampton Country Club also has a punchbowl green (https://golfclubatlas.com/courses-by-country/usa/westhampton-cc-ny-usa/), but Bendelow’s course at QFC opened 13 years earlier.

Despite playing in the opposite direction of the 1st—therefore with the prevailing wind—QFC’s first par-3 somehow always plays one or two clubs longer than the yardage. Because the green is a punchbowl, hitting and holding any part of it ensures a makeable birdie putt. Even recovery shots from the surrounding, moat-like bunkers are navigable, as the green’s contours allow the golfer to feed his ball to any pin. These rear-guard bunkers are another common feature at Quogue, acting as a check against overly bold play beyond the pushed-up greens.

Hole 3 (“Seaward”): 270 yards, par 4 / Hole 12 (“Post’s Corner”): 272 yards, par 4

Traditionally the easiest par-4 at QFC, the 3rd has been beefed up in recent years by the addition of “Church Pews” bunkering along the left side of the fairway. In theory, the Church Pews should be largely aesthetic due the shortness of the hole, as even a mid-iron tee shot with no chance of reaching them leaves the golfer with a wedge second. Only the golfer attempting to drive the green (or simply mis-clubbing) should bring the Church Pews into play. The problem with the seemingly innocuous mid-iron tee shot is twofold: (1) out of bounds and a now-lengthened lateral scar bunker guard the right side of the hole and fairway beyond, and (2) golfers wishing to avoid the right side often favor a draw, which adds distance and brings the Church Pews into reach.

From the tee, the bunkers—either the Church Pews on the left or the scar bunker cutting into the right side of the fairway—are barely visible, a function of QFC’s low-profile, flat topography.

Any shot from the Church Pews, which extend more than 50 yards, is of the awkward, long-bunker-shot variety.

The green, surrounded by bunkers on all sides and nestled into the reeds at the edge of Shinnecock Bay, is one of the flattest and largest on the course. Note the rare fronting bunker at the green’s entrance—an anomaly at QFC, but warranted at the 3rd given the shortness of the approach shot and the size of the green.

Hole 4 (“Devil’s Garden”): 193 yards, par 3 / Hole 13 (“The Creek”): 171 yards, par 3

The testing par-3 4th runs along Shinnecock Bay to a wild Biarritz-style bunkerless green that, in canting severely from right to left, has Redan properties as well. Few greens in the world of golf combine both of these classic designs. But whose design was it? We know it was not Bendelow’s; his green was surrounded by three bunkers. Could it be an homage, then, to one of the original Wilson and/or Hepburn greens? Recall that, at Shinnecock Hills, Wilson succeeded Willie Dunn, Jr., the architect of the original Biarritz in France, and that Hepburn’s nine at QFC included a Redan and a Plateau. Poetic though that option sounds, the 4th green is a new creation of relatively recent vintage, according to Mr. Murray, remodeled by two separate architects over the last several decades (Frank Duane in the 1970s and Stephen Kay in the late 1980s). In any event, the 4th not only offers QFC’s only bunkerless green, but is directionally unique to the course, running northeast and perpendicular to each of the other holes. Although a pond short left of the green seems well out of play from the tee, the prevailing right wind off the bay sends many indifferent tee balls to a watery grave. The 4th demands a pure strike.

As at the 3rd, Quogue’s flat terrain makes the view from the 4th tee unrevealing. The golfer playing the course for the first time has little idea of the contours and hazards that await.

A bay inlet some 100 yards from the tee should be mere eye candy, but more than one fatted tee ball has turned this natural hazard into a four-letter word.

Combined with the mounds to the right, the right-to-left tilt of the 4th green calls for a tee shot played to the green’s right edge. The tilt also makes navigating the Biarritz swale doubly difficult, as the golfer must judge not only the pace through the swale (the usual concern in putting such greens), but also the deeply sloping line.

Hole 5 (“The Narrows”): 412 yards, par 4 / Hole 14 (“Canal”): 470 yards, par 5

This brutal par-4 back into the prevailing wind plays more like a short par-5, asking a great deal of the golfer from tee to green. (From the “back nine” tee, the hole is a much more manageable par-5.) Because the 5th is the closest one gets to the bay and ocean at QFC, the wind is also at its strongest.

The most demanding tee shot on the course must avoid not only the reeds and bay and infamous convex bunkers to the right…

…but also the inlet from the bay on the left, invisible from the tee, that separates the 5th from the 6th.

The battle isn’t over once the golfer reaches the green, where a small false front, as well as a bisecting ridge, must be navigated. Approach shots hit long or right have a chance of being kept from the bay by another well-positioned rear-guard moat bunker.

Hole 6 (“The Marshes”): 281 yards, par 4 / Hole 15 (“Bridge Hole”): 245 yards, par 4

After the inevitable beatdown administered by the 5th, where a bogey often feels like a good score, the drivable par-4 6th provides a welcome respite. The golfer still confronts obstacles, however, albeit on a smaller scale than on the 5th, as the tee shot at the 6th is guarded on the right by reeds and marsh and on the left by the burn-like inlet that meanders the length of the hole. The 6th’s petite nature means the golfer can navigate these hazards with as little as a mid-iron. But even with a mid-iron in hand, the prevailing left-to-right wind brings the reeds more into play than one might imagine, often requiring a starting line uncomfortably close to the inlet on the left. As late as 1980, according to an aerial from that year, there were two bunkers short of the green at the end of the fairway; their subsequent removal has simplified gauging depth on the approach.

A wooden bridge connects the teeing ground to the fairway at the 6th, adding to Quogue’s walkable charm.

The slightly domed green is the 6th’s best defense. A back-left hole location, atop the dark-green strip of grass three-quarters of the way into the green on the left, is the green’s most devilish.

Hole 7 (“Cherry Grove”): 414 yards, par 4 / Hole 16 (“The Stretch”): 434 yards, par 4

Playing in the same direction as the 6th, the 7th hole is Quogue’s longest par-4, a slight dogleg-right with out of bounds lining the entire right side. A wide fairway and large, receptive green—as well as a downwind orientation—combine to make the 7th play easier than the 5th, the course’s second-longest par-4 by only two yards.

Though the 7th fairway is wide enough to make the out of bounds an afterthought, bunkers on the inside right corner (in the foreground of this reverse view) and the outside left corner tend to exert a gravitational pull on even a slightly mishit drive.

The wide, open-front green allows golfers of all abilities and lengths off the tee to play an approach shot to suit their individual style on this mid-length par-4. Note the high-lipped bunker guarding the fairway’s right side, similar to several at Garden City.

The 7th features more moat bunkering—this time to prevent overly bold shots from reaching Quaquanantuck Road. This reverse view highlights the width and playability that are foremost among Quogue’s characteristics.

Hole 8 (“Quaquanantuck”): 379 yards, par 4 / Hole 17 (“The Stadium”): 347 yards, par 4

Though measured as a short par-4 on the scorecard, the 8th often plays like a mid-length hole into the wind, as it doglegs slightly to the right. After the simplest of par-4 tee shots at QFC, the golfer is faced with a mid-iron or wedge to the largest green on the course—one that used to be even deeper, as the front third was recently converted to fairway-height grass.

A series of three strip bunkers guards the right side of this wide fairway. Some have noted the resemblance to those at Pine Valley’s 2nd hole. According to historical aerials, these bunkers appear to have been added for the first time in the 1970s (and, then, only as two before eventually becoming three).

The difficulty on the approach comes in gauging distance to the flagstick, as mounds and spectacle-like bunkers well short of the green, and newly revealed openness behind the green, complicate depth perception.

From behind the 8th green earlier in the evening, the high back lips of the three spectacle bunkers short of the green are readily visible, as is the fall off at the back of the green into another rear-guard moat bunker.

Hole 9 (“Long”): 534 yards, par 5 / Hole 18 (“Home”): 408 yards, par 4

The 9th plays slightly right to left, mirroring the par-5 1st, and across Quaquanantuck Road, only this time back home to the clubhouse. Because the hole is often downwind, reaching it in two shots is possible for the long hitter—especially due to one final inviting open-front green. But a hedgerow set menacingly close to the right-hand bunkers separates the green from the driving range and out of bounds.

The recent replacement of trees with bunkers and mounds between the 9th (right) and 1st (left) fairways gives Quogue a more expansive feel.

The proximity of the clubhouse and pro shop to the final, two-tiered green evokes a timeless tradition and ensures that efforts not to misplay an approach on the home hole will be closely watched.

After the round, golfers can enjoy drinks with broad views from the balcony atop the new clubhouse, immediately behind the 1st tee.

One final glance over the shoulder on the way out reminds the golfer that flat can indeed be beautiful.

A round at QFC should take no more than 90 minutes—and can easily last only 60. It is therefore the perfect course for weekends spent with families, the heart of Quogue’s low-key culture. One can manage a round at QFC every day, even twice a day, without interfering with, or missing out on, family plans. The flatness of the course means that the walk is easy at any age; refreshingly, push carts abound at QFC.

In my introductory post on this site, I mentioned learning at Yale not only the game but “the architecture that animates it.” What is more obvious is that land animates architecture, and that is especially true at Quogue, led by its rightfully recognized architect, Tom Bendelow. Simplicity—in the land, in the design, and in the culture of play—is what sets QFC apart. Golfers fortunate enough to play it will encounter the game’s timeless essence: Hitting a ball across an open field, finding it, and repeating the process over and over again. The name “Quogue Field Club” says it all.