MacKenzie’s Sharp Park Under Siege

A classic Depression-Era public seaside links, designed by a master, is in jeopardy

by Bo Links and Richard Harris

Sharp Park, located on Salada Beach in the San Francisco coastside suburb of Pacifica, shares the distinction with the Eden Course at St. Andrews, as the world’s only Alister MacKenzie-designed, municipal seaside golf links. But this rare and beautiful golf gem, which opened in 1932, is today under relentless political attack by a tag-team of golf-skeptics and environmental absolutists, who are demanding that the City of San Francisco plow the golf course under and replace it with a wetlands restoration project.

To save this important golf legacy, the national and international golf communities will have to rise to the occasion.

MacKenzie transformed these dunes into…

A Great Walk, Endangered

At the same time San Francisco is preparing to host the 2009 President’s Cup in October at another great public course (Harding Park), the city’s Board of Supervisors have directed the Recreation and Park Department to study the alternative possibilities of (1) closing Sharp Park, (2) reducing it to 9 holes, or (3) preserving and modifying the 18-hole course to create new habitat for threatened frog and snake species which now share the property with the golfers.

To avert the international limelight of President’s Cup media coverage, officials at Rec and Park are waiting “ until after the President’s Cup press bus rolls out of town “ before they make the study public.

In the meantime, Bay Area golf enthusiasts, historic preservationists, including the Washington, D.C.-based cultural Landscape Foundation[1], and others who treasure Sharp Park, including Pacifica Mayor Julie Lancelle, are fighting to rescue Dr. MacKenzie’s muni masterpiece. As of this writing, the battle for Sharp Park has been joined. The outcome “ with implications for golfers and golf courses everywhere “ hangs in the balance.

How in the world did we get to this point? And what can be done about it?

… one of America’s great cultural landscapes.

The Gold Rush, A Gift, and The Making of Sharp Park

Sharp Park Golf Course occupies approximately 120 acres of a 400 acre park “ most of it forested wilderness “ bequeathed to the City of San Francisco in 1917 by the executors of the estate of Honora Sharp, the widow of George Sharp, a prominent San Francisco attorney who sailed around Cape Horn and arrived in San Francisco in 1849. He made a fortune during and after the Gold Rush but dropped dead in a local courtroom while pleading a case in 1882. The gift from Mrs. Sharp’s estate is subject to the condition that the property will revert to the Sharp family heirs unless it is used exclusively for a public playground or park.

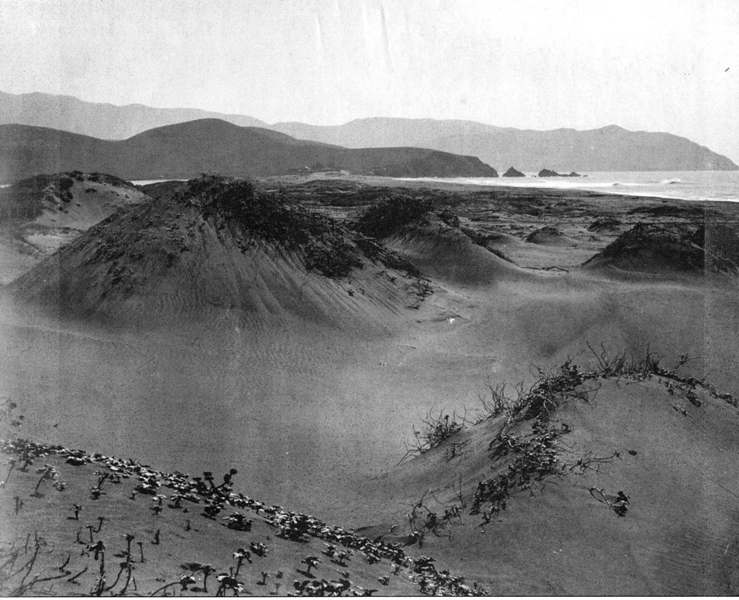

Historic photographs show that before the golf course, the land was predominantly a barren and deserted stretch of sand dunes surrounding the Laguna Salada (Spanish for salty lake), a brackish lagoon located in an area designated on the 1892 US Geological Service topographic map as Salt Valley.[2]

In 1930, when San Francisco’s two existing public courses at Lincoln Park and Harding Park were oversubscribed with enthusiastic golfers, the man who created Golden Gate Park had a brainstorm. Why not build a third course on the land that had been donated by Mrs. Sharp? So John McLaren, the legendary steward of San Francisco open space and parkland, floated the idea of a seaside public golf course at Sharp Park. McLaren’s handpicked architect, Dr. Alister MacKenzie, was retained by unanimous vote of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors to build the City’s third municipal course in the dunes at Salada Beach.

You will never see a more eclectic group of golfers anywhere.

MacKenzie was by then a Bay Area resident, with an office in Oakland, and a recent string of Northern California architectural successes, including Cypress Point (1928), Pasatiempo (1929), Claremont (Oakland, 1929, remodel) Lake Merced (Daly City, remodel 1928-29) California Golf Club (South San Francisco, remodel 1928), and Meadow Club (Fairfax, 1926).

Dr. MacKenzie designed Sharp Park in 1930-31, leaving construction supervision to his partners Chandler Egan (two-time U.S. Amateur champion, 1904 Olympic golf silver medalist, and designer of a string of outstanding courses in Oregon and Washington) and Robert Hunter, both of whom worked with MacKenzie when he remodeled Pebble Beach for the 1929 U.S. Amateur Championship. They were joined by Jack Fleming, who had been the construction foreman at Cypress Point.

The Good Doctor’s Golf Prescription: beauty, fun, accessibility and pleasurable excitement

Born in 1870 in Yorkshire, England, Alister MacKenzie received a medical education at Cambridge, and served as a British Army surgeon in the Second Boer War in South Africa in the 1890s. He later quit the practice of medicine and went into partnership in turn-of-the-20th-century London with H.S. Colt the first-ever business dedicated solely to golf architecture.

One of the reasons why I, a medical man, decided to give up medicine and take to golf architecture was my firm conviction of the extraordinary influence on health of pleasurable excitement, especially when combined with fresh air and exercise, MacKenzie explained. How frequently have I with great difficulty persuaded patients who were never off my doorstep to take up golf, and how rarely, if ever, have I seen them in my consulting room since.[3]

As consulting architect at St. Andrews in the early 1920s, MacKenzie was the first to chart the swales, hollows and pits which characterize the fairways of the Old Course. Golf in its early days was always played on commons or links land which bordered the sea, MacKenzie explained. The natural characteristics of this type of land made it easily the most suitable for the game.[4]

Golfers the world over have come to know Dr. MacKenzie as one of history’s greatest golf architects, whose courses circle the globe from New Zealand (Titirangi) to Australia (Royal Melbourne and New South Wales) to Argentina (The Jockey Club) to England (Alwoodly and Moortown), Ireland (Cork and Lahinch) and, of course, Scotland (Blairgowrie, and his work at St. Andrews, including assisting H.S. Colt in designing the Eden Course).

MacKenzie in America

In the United States, Dr. MacKenzie worked primarily in the Midwest (where he built university courses at the University of Michigan and Ohio State, and the great layout at Crystal Downs in Northern Michigan) and California. Indeed, his final resting place is Santa Cruz, overlooking Monterey Bay, 90 miles south of San Francisco, where his ashes were scattered at Pasatiempo, the wonderful up-and-down course he built for Marion Hollins. Bobby Jones played Pasatiempo on opening day in 1929 and it was that experience, as well as the fact that MacKenzie (working again for Mrs. Hollins) had also recently designed the amazing new course at nearby Cypress Point, that caused the game’s greatest amateur (and some say greatest player) to retain MacKenzie to construct Jones’s dream course, Augusta National, on an abandoned nursery in rural Georgia.

In 1920, MacKenzie published “Golf Architecture,” the first-ever book on the subject of golf course design, in which he enumerated key principles of golf architecture, including:

- The course should have beautiful surroundings

- [T]he course should be arranged so that the weaker player with the loss of a stroke, or portion of a stroke, shall always have an alternate route open to him”

- “[T]here should be a complete absence of the annoyance and irritation caused by the necessity of searching for lost balls” and

- “[T]he long handicap player or even the absolute beginner should be able to enjoy his round in spite of the fact that he is piling up a big score.”[5]

Dr. MacKenzie was a devotee of natural beauty, and an artist in the tradition of Lancelot Capability Brown, the 17th Century father of English naturalistic landscape design. The chief object of every golf architect or greenkeeper worth his salt, MacKenzie said, “is to imitate the beauties of nature so closely as to make his work indistinguishable from Nature herself.”[6]

“My reputation, he continued, has been based on the fact that I have endeavored to conserve the existing natural features and, where these were lacking, to create formations in the spirit of nature herself. In other words, while always keeping uppermost the provision of a splendid test of golf, I have striven to achieve beauty . . . . This excellence of design is more felt than fully realized by the players, but nevertheless it is constantly exercising a subconscious influence upon him and in course of time he grows to admire such a course as all works of beauty must be eventually felt and admired.”[7]

An ardent advocate of municipal golf, MacKenzie hope[d] to live to see the day when there are the crowds of municipal courses, as in Scotland, cropping up all over the world. There can be no possible reason against, and there is every reason in favor of, municipal courses.[8]

Unfortunately for public golfers, MacKenzie worked mostly for private developers, so very few of his courses are publicly accessible. Most golfers only hear about MacKenzie’s greatness when the world’s best play the Masters every April at Augusta National. Similarly, most American golfers never get closer to a genuine seaside links than their couches and TV sets every summer during the British Open.

The Miracle at Salada Beach

But for the past 77 years, lucky San Francisco muni players and visitors have had Sharp Park “ the Pacific Coast’s answer to North Berwick “ a place where a remarkably diverse golfing clientele of all races, languages, social classes, and genders pull their carts, hit their shots, and enjoy a beer and a sandwich in a charming 19th hole pub, for a modest weekday greens fee under $30. The Spanish hacienda-style clubhouse was a Works Progress Administration construction project, designed by an associate of Willis Polk, who in turn was head of the San Francisco office of Chicago-based master planner Daniel Burnham. In other words, when constructing Sharp Park “ in the dark days of the Great Depression “ San Francisco went first-class all the way.

The clubhouse at Sharp Park is a WPA classic.

As for the course design, Dr. MacKenzie made the most of the opportunity handed him by John McLaren. Deploying state-of-the-art machinery and innovative engineering techniques, he dredged the Laguna Salada, converting it from a brackish marsh into a fresh water lake, then set about surrounding the lagoon with golf holes. Sharp Park incorporates MacKenzie’s prescription that a golf course should be a place of surpassing natural beauty, and that the game should foremost be a fun and healthful pastime, equally playable and enjoyable by persons of all abilities.

At Sharp Park, MacKenzie combined features in one place that he had scattered over other layouts. His original design included holes featuring multiple tees (Nos. 2, 5, and 14), double fairways (Nos. 5 & 10), cross bunkering (No. 16), fairways in the sand dunes (Nos. 3 & 7) and several holes bordering the inland lake (Nos. 4, 5, 8, 9, 10 and 11). There were tees on spits in the water, and island landing areas. Two of the holes were clearly inspired by MacKenzie’s Lido Hole which catapulted him to fame in 1914 when he won a design contest sponsored by Country Life magazine.

Looking at Sharp Park is like viewing a John Constable painting of an English landscape.

The plans were drawn in 1930-31, and while MacKenzie was attending to business in Europe, his colleague Chandler Egan supervised construction. Egan marveled at the site’s remarkable seascape, prompting local reporters to refer to the course as a second St. Andrews. Everyone associated with the project fully intended it to become the finest municipal golf course in America.[9]

Indeed, local press reports analogized the effort to build Sharp Park as nothing less than an attempt to bring a touch of Scottish coastland on the Pacific Shore. One report said the joint effort of McLaren and MacKenzie would create a seaside municipal course of outstanding character akin to those of the English and Scottish coasts.[10]

When the course opened for play on April 16, 1932 it played 6,173 yards to a par of 71. The local press echoed Egan’s theme, noting that the course presented a thorough test of golf and a perfect seaside layout. One report commented that [p]icuresque dunes and a lagoon or so dot the landscape to add their charm and hazards to the golfer’s day.[11]

Modern architectural scholars have come to regard MacKenzie’s design at Sharp Park as one of America’s greatest public courses. Daniel Wexler, America’s leading exponent of lost courses, has lauded Sharp Park as a marvelous golf course, featuring seaside holes, two double fairways, a large lake, and a cypress-dotted setting fairly reminiscent of Monterey. It was, in short, a municipal masterpiece.[12] In a call for restoration, Wexler observed, after surveying hundreds of public and private courses from coast to coast, that the original Sharp Park would have to stand well out in front as America’s finest municipal golf links.[13]

Tom Doak, perhaps the country’s most noted authority on golf course renovation, has cited Sharp Park as a milestone, evidencing an evolution in Dr. MacKenzie’s style even at the height of his fame as the country’s most sought-after golf architect.[14]

One of today’s most prolific golf architecture critics, Geoff Shackelford, echoes these themes, saying: Certainly no municipal-course design has ever come close to matching the overall package of beauty and affordable links-style golf. [15]

MacKenzie himself, in his comprehensive (and long lost) manuscript, The Spirit of St. Andrews, praised Sharp Park and San Francisco’s public golf facilities in general:

“The municipal courses in San Francisco are far superior to most municipal courses. The newest, which we constructed at Sharp Park, was made on land reclaimed from the sea. The course now has a great resemblance to real links land.” [16]

This sea wall protects the course from the ocean, which is only a wedge shot away. Two of MacKenzie’s original holes were right on the beach, but erosion and flooding forced the City to move inland with the construction of four new holes in 1941.

Urban legend long had it that portions of the original course were washed away in the 1930s by powerful winter storms. But in truth, the course weathered the storms until 1941, when the original strand holes (Nos. 3 and 7) were replaced by an unreinforced sea wall, and four excellent new holes were built by MacKenzie’s associate Jack Fleming, who by then had become San Francisco’s supervisor of golf. The new holes were built (following MacKenzie’s death in 1934) in a canyon east of the rest of the golf course, located on the other side of what was then state Highway 1. (An aerial photograph taken in March 1941 shows the original course still intact; the picture was taken just prior to the building of Fleming’s four new holes.)

Sharp Park Today

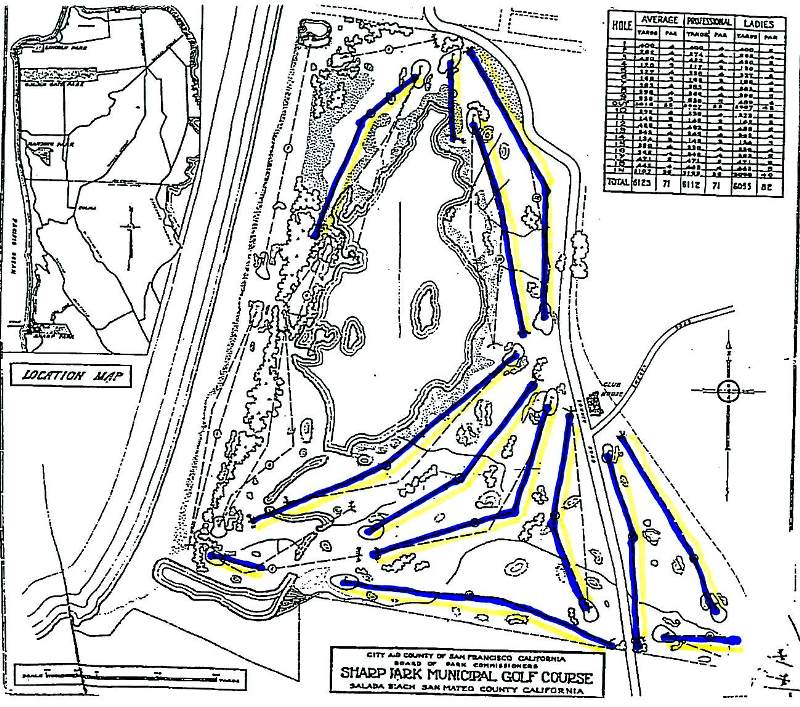

In 2009, twelve of Sharp Park’s current 18 holes are MacKenzie originals, and an additional two holes lie in original fairways, but without original greens. While the course has seen trees mature, traps grassed-in, a stream or two culverted, and withstood other relatively minor insults of the golf course aging process, the unmistakable fact is that 14 of 18 holes track MacKenzie’s original routing. A comparison of the present-day course with the original routing maps proves the point, as do the hole-by-hole descriptions penned by Jack Fleming for one of the San Francisco newspapers for the course opening in 1932.[17]

Those familiar with MacKenzie’s style will immediately recognize the Good Doctor’s trademark heaving, tumbling greens at current holes 1, 2, 3, 9, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 17, and 18. Fairway undulations and mounds on current holes 1, 3, 9, 10, 14, and 16 mimic the famous fairway bumps and hollows at the Old Course at St. Andrews. And the deception bunker 50 yards in front at the right side of the current 14th green is a classic bit of MacKenzie’s renowned use of camouflage principles.

A walking tour of the current course not only reveals the original green contours and the locations of original bunkers, but a detour through the ice-plant strewn sand dunes in the shadow of the sea wall also reveals three of the lost holes abandoned in 1941 when the new holes were built east of Highway 1.

The lost holes are there, waiting to be reclaimed!

Overarching the design details at Sharp Park is MacKenzie’s beautiful landscape architecture. The Monterey Cypress that define several fairways[18] frame picturesque views of the mountains and headlands surrounding the low-lying golf course. It is as if the Good Doctor had set the fortunate golfer down in the middle of an early 19th Century English romantic landscape painting by John Constable.

This picture shows portions of the original 4th and 8th holes.

Although time and underfunded maintenance have taken the edge off many of the original features, Sharp Park is still unmistakably a great golf course“ a MacKenzie classic, and an American masterpiece. But it is more than that. Sharp Park incorporates Dr. MacKenzie’s faith in the capacity of public golf to help enormously in increasing the health, the virility and the prosperity of nations . . . .[19] It is a public golf companion piece to the Golden Gate Bridge: a monumental engineering and artistic feat, created in the depths of the Great Depression by a great artist, to inspire and uplift the public spirit.

This shot is in the vicinity of the original (and lost) fourth green. Are we standing in a MacKenzie bunker?

In the throes of the Great Recession of the early 21st Century, the Good Doctor’s Golf Prescription remains timely.

Who Would Want to Destroy Such a Place?

A golf course is real estate. Those who hold it eventually have to contend with those who covet it. That time has arrived for Sharp Park.

The charge to destroy the golf course is lead by powerful forces, including the San Francisco Neighborhood Parks Council, a public parks advocacy organization, funded partly by taxpayer dollars, whose founder and spokeswomen Isabel Wade has publicly denigrated golf as “predominantly a male sport and frankly … a white sport” and not a family-oriented sport that you do with other folks.[20] Joining in the attack is the Tucson-based Center for Biological Diversity, a controversial organization specializing in Endangered Species Act litigation, which in September, 2008 issued a notice-of-intent-to-sue-letter to the City of San Francisco, alleging depredations to the endangered San Francisco Garter Snake and California Red-legged Frog at the golf course. The running drama of the CBD’s threats and its related campaign to turn the golf course into a dedicated frog and snake preserve, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors May, 2009 Ordinance directing study of development alternatives at Sharp Park, and the golf communitys reaction, is described in detail in recent news reports.[21]

To be sure, the snake and frog are federally-listed, and are reputed to live in and about the ponds on the golf course, and on land adjacent to the course. And for their part, the golfers and golf course supporters think that golfers, snakes, frogs, and All God’s Creatures can live and let live at Sharp Park, and that the creatures native habitat and the historic golf course can both be dramatically improved, for he benefit of all.

But there is considerable irony here. The snake and frog are freshwater species, and historic photos show that before the golf course, the area was mostly barren dunes surrounding the brackish Laguna Salada. According to scientific studies, Laguna Salada prior to the golf course was unlikely to have been home to either species, due to the high salt content of the water.[22] And the first scientific records of the San Francisco Garter Snake at the property are studies made in the mid-1940s[23]long after golf course irrigation and the construction of the first sea wall in 1941 had changed Sharp Park’s hydrology from brackish to freshwater.

A west coast version of The Old Course.

So now the environmental absolutists campaign to drive the golfers off and close the very golf course that attracted the frog and snake in the first place, strikes golfers as beyond common sense, and beyond responsible science. It is Out of Bounds.

Reflections – And a Call to Action

Whether the golfers will be able to keep the course or whether it will be converted to a frog and snake preserve are real political questions in San Francisco and in Pacifica.

Unless the golfing world stands up to demand preservation of Dr. MacKenzie’s historic seaside public links, and unless money is raised within the golfing community to help preserve golf at Sharp Park while at the same time enhancing natural habitat for the endangered species in and about the property, this great work of golf’s greatest architect will be lost forever.

If a golf course with Sharp Park’s historic legacy and devoted multicultural clientele can be destroyed by a combination of anti-golf prejudice and over-aggressive use of the Endangered Species Act, no golf course is safe. For these reasons, the San Francisco Public Golf Alliance solicits the support of golfers everywhere to save this municipal masterpiece.

For more information, contact either Bo Links (bo@slotelaw.com) or Richard Harris (richard@erskinetulley.com) or go to our website (www.sfpublicgolf.com). Once there, sign up for updates, make your voice heard, and contribute your support to the cause.

HOLE DESCRIPTIONS

As shown on this map of the original MacKenzie layout, 12 of the original holes are still in play. A portion of another hole is in use, and remnants of several “lost holes” remain in the dunes west of the lagoon.

Written by Jack Fleming

As published in the San Francisco Call-Bulletin, 1932

Hole 1 (current 11th hole) – 409 yards – Par 4

A fairly long two shot hole slightly dog legged. No particular difficulties to a straight hitter.

This was the original opening hole, and a test at that: over 400 yards back in 1932.

Hole 2 (current 12th hole, shortened to a 3-par) – 262 yards – Par 4

This hole original was a short par 4 with double tees and a routing that crossed a corner of the lagoon. Today, it is a stout three par, backed against the sea wall with ocean breezes always in play.

A short two shotter. Drive must clear an arm of lake at about 100 yards, but a wide fairway available at 175 yards out. Green set back against trees and trapped in right front.

Hole 3 (lost) – 420 yards – Par 4

One of the ocean holes constructed on the beach in a slight depression bounded by sand and sand grass embankment on left, trees on right. Entrance to green slightly advantageous from left on account of traps.

Hole 4 (lost) – 120 yards, Par 3

A one shotter. Green very large, but well trapped in front and right, trees left and rear.

Hole 5 (current 17th hole) – 327 yards – Par 4

This hole was one of two that MacKenzie modeled after his famous “Lido Hole“ the design entry he submitted in 1914 to Country Life magazine that launched his career.

A lakeside hole and one of the most interesting holes on the course, similar to Dr. MacKenzie’s ideal golf hole [a reference to the Lido Design]. Three tees, four routes. Easy route probably will cost at least one extra stroke to get on while the other combinations of tees and routes give rewards proportionate to their respective risks.

This hole was one of two that MacKenzie modeled after his famous “Lido Hole” the design entry he submitted in 1914 to Country Life magazine that launched his career.

Hole 6 (lost) – 158 yards – Par 3

A difficult par. Green well trapped.

Hole 7 (lost; paralleled current 16th hole) – 383 yards – Par 4

Similar to No. 2, but in opposite direction. A trap endangers the short player on his second, but properly played as a two shot hole a par is possible.

Hole 8 (lost) – 398 yards – Par 4

A dogleg, quite difficult for two shots. Drive is blind and over trees if played close to get in opening for a good second. Plenty of fairway, however, for those who play short and do not care to risk trees on right for possible par. The wide play practically requires three strokes to get on.

Hole 9 (current 13th hole) – 538 yards – Par 5

The modern day 13th as viewed from behind the old 9th tee.

A lakeside hole with wide, sandy beach on water side. Back tee should be used by all, as water carry is very short and close to tee. Requires three good shots to get on if dogleg is played, but possibly a very long sure approach will get in under par.

Hole 10 (current 14th hole – left fairway now part of marsh) – 382 yards – Par 4

This is the other hole MacKenzie modeled after his Lido Hole. The original design, like that of the original 5th hole, featured two fairways. The one on the left, closest to the lagoon, was a peninsula much like the Lido design. It offered the shorter route to the green, a temptation for the adventurous player. Today, the lagoon feature has been lost, but the hole still presents a challenge as it follows a gentle curve around the hazard. A mound and camouflage bunker protect the green.

One of the best holes, two tees, four possible routes, sand and water carries optional. The ideal shot is an accurately placed ball on an island with a water carry on both first and second shots. If well placed on first, the green opens well for a pitch and run second. All other approaches to the green are guarded.

Hole 11 (currently 15th hole) – 142 yards – Par 3

A fairway-less short hole. Water and sand carry, trap green. Green, however, is long and should receive an average straight ball easily.

Hole 12 (current 18th hole) – 486 yards – Par 5

Fairway flat, double dogleg. Not difficult except to get two good straight drives in succession.

Hole 13 (current 3rd hole) – 345 yards – Par 4

Passing the clubhouse from No. 12 green to No. 13 tee. The thirteenth, fourteenth and fifteenth are all holes of a different type than the lakeside and ocean holes. No 13 is an upland type of hole of average difficulty. The green is well trapped.

Hole 14 (shortened; current 8th hole) – 134 yards – Par 3

This sporty par 4 was originally the 14th hole. The green is well protected and one can readily see how MacKenzie’s original green must have heaved and flowed with the bumps and hollows that are there today.

This short hole has two tees. The tee with the carry across the creek opens into green easily, while on crossing creek to the other tee a more difficult shot over a trap at the green is encountered. Directly into prevailing winds.

Hole 15 (current 2nd hole) – 339 yards – Par 4

Originally the 15th hole, this is another mid-range four par to a green that was a MacKenzie classic: rolling and undulating to provide no end of excitement for players of all abilities. There are indications on the ground today to indicate that the original green most likely wrapped around the bunker, which itself was shaped somewhat like a cloud another Mackenzie hallmark.

Similar to No. 12. At present along the edge of the county road, which it is planned to re-locate. No. 15 green is near clubhouse.

Hole 16 (current 1st hole) – 363 yards – Par 4

A nice hole with two optional routes and a creek to cross.

Hole 17 (current 9th hole) – 471 yards – Par 5

This par 5 was the original 17th hole. The green is framed beautifully by cypress trees, planted by John McLaren, the man who created Golden Gate Park. MacKenzie credited him with planning around the golf course to enhance the beauty of the natural landscape.

A long hole down the south property line. The green is on a 15 foot fill.

Hole 18 (current 10th hole) – 443 yards – Par 4

The finishing hole is long and hazardous if not successfully played on both long shots, but the green is wide, open and nicely rolling in order to lend interest to the many thrilling final decisions which will no doubt be made on it. A clump of trees guards the green on the left.

This 1941 aerial photo shows that the urban legend of the course washing away shortly after it opened, is a myth. The picture shows the original course almost fully intact prior to the creation of four new holes inland, on the other side of a state highway.

The End

[1] Landslide, The Cultural Landscape Foundation, “Alister MacKenzie’s Sharp Park, July, 2009. [Note: links to this and all sources cited can be found in the News and Resources section of the San Francisco Public Golf Alliance website: http://www.sfpublicgolf.com/news.html]

[2] Williams & Associates, Laguna Salada Resource Enhancement Plan, ( June, 1992) , at pp.2-3, and Fig. 2.

[3] Alister MacKenzie, The Spirit of St. Andrews, (Sleeping Bear Press 1995) at p. 246

[4] Id. at p. 1.

[5] Id. at p. 41-42.

[6] Id. at p. 50.

[7] Id. at p. 51.

[8] Id. at p. 250.

[9] “H. Chandler Egan Praises Possibilities of Sharp Park Golf Links (sub-head: New Municipal Course Ideal Claims Expert, San Francisco Chronicle, February 26, 1930, page H-3.

[10] Appropriation For Third S.F. Golf Course Receives Okeh, San Francisco Examiner, February 22, 1930, page 15.

[11] “New San Francisco Course Opens, San Francisco Examiner, April 16, 1932, page 17.

[12] Wexler, The Missing Links (Sleeping Bear Press 2001) at p. 113.

[13] Id. at p. 116.

[14] Doak, The Life and Work of Dr. Alister MacKenzie (Sleeping Bear Press 2001) at p. 154.

[15] Shackelford, Sharply Divided, Golf World, July 20, 2009, at p. 31.

[16] MacKenzie, The Spirit of St. Andrews (supra, fn.3) at p. 171-172.

[17] Tee Topics (sub-head: Here’s What You Find at Sharps [sic] Park – Fleming Describes City’s Newest Layout), San Francisco Call-Bulletin, March-April 1932. The hole-by-hole descriptions are included at the end of this article.

[18] The Spirit of St. Andrews (supra, fn. 3) at pp. 171-172.

[19] Id. at p. 250.

[20] KQED Radio, Aug. 31, 2007, “The Future of Public Golf in San Francisco.â€

[21] KGO TV (ABC), The Fate of Sharp Park,†August 12, 2009; Geoff Shackelford, Sharply Divided, (supra, fn. 15); Curt Sampson, Sharp Elbows: Environmentalists and Golfers Square Off Over Sharp Park, Sports Illustrated, May 11, 2009 at pp. G-3-G-5.

[22] Williams & Associates, Laguna Salada Resource Enhancement Plan, (supra, fn. 2), at pp. 2-3.

[23] Swaim Biological, Sharp Park Wildlife Surveys, etc. Dec. 4, 2008, at p. 1.3-1.4.

THE END