Joshua Crane In The Golden Age, Part I

by Bob Crosby

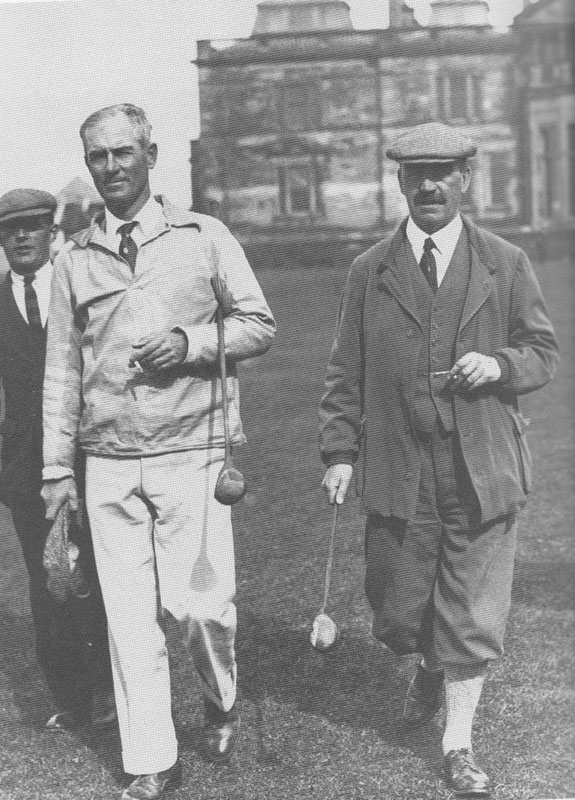

Three men met in St Andrews in the summer of 1929. They were antagonists in one of the most remarkable debates in the history of golf course architecture. One of the men was Alister MacKenzie, the best known golf architect of the era. MacKenzie was there with his friend Max Behr, heir to a paint fortune (the company still bears the family name) and a first rank amateur player. Behr had once been the editor of the US version of Golf Illustrated but was now working as a golf architect in California. A picture of the two men striding down the first fairway of the Old Course that summer shows MacKenzie, the shorter of the two, wearing a rumpled hunting jacket and vest. Behr has removed his cap for the photographer. He has a movie star’s good looks and is wearing a zippered, modern pullover.

The third man in St Andrews that summer was Joshua Crane. A wealthy Bostonian, Crane had been a star running back on the Harvard football team, a world class tennis player, polo player and yachtsman. Now some twenty-five years after his athletic triumphs Crane was still thin and fit. His decision to take a flat in St Andrews that summer had raised eyebrows in the world of golf. Several years earlier Crane had rated fourteen prominent British courses and the Old Course had finished dead last. It had all caused quite a stir. Bernard Darwin noted at the time that if Crane’s rankings really reflected his views, deciding to spend his summer playing golf in St Andrews was an odd choice indeed.

Joshua Crane at the International Seniors Match, 1928

We don’t know exactly what the three men said to each other that summer, though MacKenzie recounted some of their conversations in The Spirit of St Andrews. Their earlier exchanges on golf architecture in the pages of the most prominent golf magazines of the time had gone from polite, to acrimonious, to personal. The devolution in tone might have been predicted. All three were supremely confident of their views and had little patience with misbegotten souls who might disagree with them. So it seems likely that their conversations that summer were, as they say, animated. Nor did their meetings in St Andrews resolve their differences, though their fracas was to have a surprising final act five years later.

Their disagreements exemplify the unsettled state of things in the Golden Age. The period was not, as its name suggests, a time of harmony and good feelings. To the contrary, people argued about virtually everything. They fought about amateur standing, stroke and distance penalties, the stymie, the rubber core ball and steel shafts. And, of course, they argued about golf architecture. There was little consensus about the criteria for good golf course design. The length of holes, how and why different bunkering schemes ought to be used, blind shots and other issues were hotly debated. Part of the turmoil was due to the fact that the basic vocabulary for the “new art of golf architecture” was just being worked out. Architectural concepts we now take for granted were still unresolved and people argued over them, often bitterly.

And something else was going on. It had to do with golf’s uneasy relationship with other sports. Joshua Crane was one of the great sportsmen of his generation, among the first of the type in the United States. Along with other wealthy sons of the Gilded Age, it was a point of pride for Crane and his circle to compete in a wide variety of sports, golf being prominent among them. But Crane thought golf presented unique problems. He worried that too many golf courses failed to assure competitive “fairness.” If golf courses were to function as venues for true sporting competitions, he thought it important that the linkage between golf shots and their outcomes be as rational and predictable as possible. Why, Crane asked, shouldn’t concerns with competitive equity that were so important in other sports apply with equal force to golf?

Views similar to Crane’s had been around for a while and they had co-existed peacefully with other, conflicting ideas about golf design. Crane ended that peaceful co-existence, however, and brought long-standing differences to a head. He did so in three ways. First, Crane got everyone’s attention by claiming he had unmasked serious deficiencies in the Old Course and other historic links courses. Crane then claimed that the methodology he used to obtain such results was “objective” and the standard against which the quality of all golf courses should be measured. Finally he suggested that courses that didn’t satisfy his objective standards were not suitable venues for true sporting competitions. Crane framed disagreements about golf design as a pass/fail test. Among the courses that failed his test were the most beloved golf courses in the world.

Crane’s controversial course rankings were reported in all of the major golf periodicals on both sides of the Atlantic and they triggered a number of battles. Those battles have much to teach us. The best of them forced the antagonists to examine basic concepts in golf architecture with a thoroughness that has never been equaled. Neither before nor since have so many articulate, well-informed commentators engaged in a point-counterpoint public exchanges over foundational issues in golf architecture. Both sides thought that the future of golf architecture was at stake and their passion still leaps from the page. Perhaps that is why they drilled down to the central issues in golf architecture more perceptively and more honestly than any public debate about golf architecture before or since.

Crane’s Course Rankings

Joshua Crane was an unlikely protagonist in an acrimonious public debate about golf architecture. In his youth his sporting interests were with tennis, polo, yachting, football and track. Crane was a gifted athlete and he participated in all of those sports at high levels in national and international competitions. Though he did not take up golf until adulthood, Crane quickly became a very good player. He captained five Lesley Cup teams from Boston and played regularly in amateur tournaments in Britain and the US. After World War I Crane began spending more time at his residence in London. While there he toured the famous courses of England and Scotland, keeping detailed records of their physical features and conditioning. Those records became the raw data on which Crane based his initial set of course rankings of fourteen British courses. Crane published those rankings and explanations of his rating methodology in Field, Britain’s pre-eminent “Gentleman’s Weekend” magazine, over a three year period beginning in April, 1924 and continuing into the summer of 1927.

Crane’s initial ranking of British courses was probably the first course ranking that claimed to be more than a simple popularity contest.[1]

That would have been controversial enough. But Crane went further, claiming that his rankings weren’t just his personal opinion of the quality of the fourteen courses considered. To the contrary, Crane presented his rankings as “scientific.” Assigning values to a multitude of carefully measured physical features of each course and then cranking those values through a complicated weighting formulae, Crane believed he had generated an “objective” ordering of the courses under review. With the result that Muirfield and Gleneagles were found to be two best courses in Britain. The two worst, by wide margins, were the Old Course and North Berwick. Crane’s first full course ratings went as follows:

Muirfield 86.5

Gleneagles 84.6

Prince’s 83.8

Troon 83.0

St. George’s 82.1

Hoylake 81.5

Walton Heath 80.4

Sunningdale 80.1

Turnberry 79.9

Deal 79.1

Prestwick 78.1

Westward Ho! 75.3

North Berwick 72.6

St. Andrews 71.8

Crane wrote frequently for Field, setting out his rankings, his rating methodology, hole-by-hole analyses of each of his ranked courses and responding to his critics. In the late 1920’s he expanded his rankings to include Pine Valley, National Golf Link of America, The Lido and other US courses. Crane also identified a course composed of his “ideal” holes, eventually applying his rating system to a hypothetical course made up of those holes. During 1926 and 1927 Crane authored several articles and lengthy letters in Country Club & Pacific Golf and Motor Magazine, most responding to Max Behr in a furious debate they carried on in the pages of that magazine. Crane’s writing on golf went beyond golf architecture, however. He also wrote on handicap systems (rather than stroke adjustments Crane advocated the use of different tees, an idea that spurred a response by Bernard Darwin in The Times), rules interpretations, the golf swing, and putting.

Crane’s final, composite ranking of British and American courses, including his hypothetical ideal course, as it appeared in 1928:

Ideal US course 95.9

Muirfield 86.5

Gleneagles 84.6

Prince’s 83.8

Troon 83.0

The National 83.0

Merion 82.6

St. George’s 82.1

Hoylake 81.5

Pine Valley 80.9

Lido 80.7

Walton Heath 80.4

Sunningdale 80.1

Turnberry 79.9

Kittansett 79.4

Deal 79.1

Prestwick 78.1

Myopia 77.7

Essex 75.6

Westward Ho! 75.3

Essex 73.5

North Berwick 72.6

St. Andrews 71.8

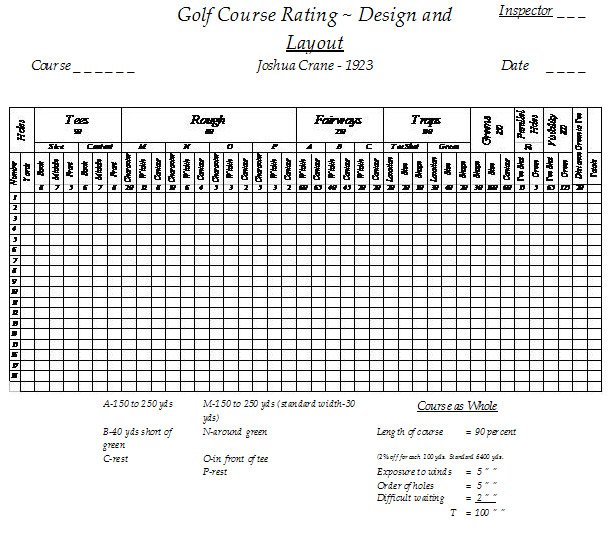

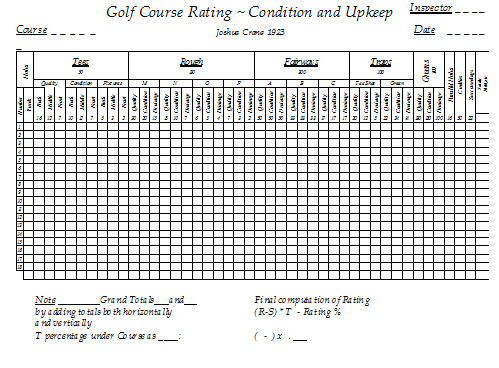

The detail that went into Crane’s course evaluations is mind-boggling. Equally mind-boggling were the elaborate weighting formulae used to assign values to each measured feature. Those values were then tallied to generate an overall “objective” rating percentage for a course, which percentage indicated the degree to which the course fell short of Crane’s ideal for design, conditioning and other matters. Crane published his full checklists in the US Golf Illustrated in 1925:

The data Crane collected on course conditioning was equally detailed:

When Crane did his actual rankings he relied most heavily on his Design and Layout data. He was concerned that the data he had gathered on Conditioning and Upkeep was out of date and likely to be inaccurate by the time his final rankings appeared. As for the methodology itself, it’s not clear how a number of categories are supposed to interact. For example, how Crane distinguished “quality” from the “condition” and “drainage” of various features is not elaborated. Indeed, how a number of categories interact with each other is not well explained. Also to be noted is Crane’s curious addition of rating categories for things like caddies and course surroundings, things that might make sense in most rating systems, but not one that purported to be objective.

First Responses

Crane’s rankings evoked a range of responses that played out over several years. The very idea of a course ranking on based solely on design quality was novel, and some commentators thought that any such program was misguided from the outset. Compounding things was the low ranking Crane gave to the Old Course and other historic links courses. Anyone ranking golf’s sacred sod at the bottom of the heap should have expected strong reactions. But to then pour gasoline on the fire by claiming your rankings were “objective” and “scientific” was what it meant to go cruising for a bruising.

And that’s what Crane got. The initial responses to his rankings were almost universally hostile. Charles Ambrose, a frequent contributor to the Field and Golf Illustrated, wrote about Crane’s ranking of the Old Course that “So far there is not one single hole which escapes Mr. Crane’s strictures. The imagination fairly boggles at the thought of the spectacle the poor Old Course would present after Mr. Crane had flattened it out to his liking.”

Crane shot back that Ambrose had attacked him personally and failed to address the merits of his rankings:

“[Ambrose’s] type of mind is that of a believer in spiritual mediums, who when a calm scientific investigation has been undertaken with a view of proving or disproving facts…, and the medium has been detected (as they all have been sooner or later) in fraud, rushes to the defense by claiming that the investigating committee was to discredit the medium…”

Crane didn’t publish his full hole-by-hole analyses of the Old Course and Muirfield (the worst and the best courses in his rankings) until more than a year after his first essay on his methodology had appeared in Field in 1924. When his analyses for those courses did finally appear, there was another surge of criticism. But it wasn’t all just shouting and hand waving. Crane’s ideas were thought important enough for Field to get reactions to his rankings from Harry Colt, J.R. Abercromby and MacKenzie. Ambrose conducted the interviews and introduced them as follows:

Muirfield has been placed by Mr. Joshua Crane as the head of British golf courses. (Field, September 24th, 1925, February 4th, 1926) and St. Andrews (November 19, 1925) considerably below it. St. Andrews is very much what it has always been as a Championship course, except for minor alterations. Muirfield has been within the last year or two overhauled and reorganized by Mr. H. S. Colt, the golf architect. Clearly it would be of interest to ask Mr. Colt if he had any plan which would bring the Old Course at St. Andrews to the scientific level of the new Muirfield.

Colt and MacKenzie, contra Crane, thought that no changes should be made to the Old Course and that it remained a model for good design.[2] Colt’s response was particularly interesting because his “up-dating” of Muirfield had deeply impressed Crane and received his highest rating. Crane often referred to Muirfield as the model for how older links courses ought to be “modernized.” Colt, however, did not think such ideas had application to the Old Course:

… I think that the Old Course is so unique that any attempts to graft on new ideas would never be a success. It has served its purpose for centuries by providing healthy exercise and enjoyment to vast numbers of people, and at the same time a test for Championship golf.

MacKenzie echoed Colt’s views, stating that “I don’t think anyone has studied the Old Course at St. Andrews more than I have, and the more I reflect the less inclined I am to alter any of the holes.”

Down the street at the British Golf Illustrated Harold Hilton dismissed Crane as an American expatriate with no business ranking Britain’s historic courses. The US Golf Illustrated reproduced some of Crane’s articles first published in Field, including Crane’s description of his ranking methodology. The editors of the US Golf Illustrated were less hostile than their British counterparts to Crane’s project, publishing not only his detailed ratings of a number of US courses, but also his rating data checklists and two pieces written by Crane on his ideal holes.

Alister MacKenzie had just finished his extraordinary map of the Old Course when Field began to roll out of Crane’s rankings. The map had been a labor of love for MacKenzie, taking him more than a year to complete. It was his lifelong conviction that the Old Course was the standard against which all golf courses should be measured. It would be expected, then, that MacKenzie would be upset with Crane’s findings:

I have recently seen an article by Joshua Crane on the rating of famous golf courses. It is difficult to read the article without a feeling of intense [irritation]… He rates Muirfield as the best and poor old St Andrews as the worst of our famous golf courses, whereas any architect in Britain or America who has achieved any marked success in creating popular courses will reverse his rating.

MacKenzie concluded acerbically:

…it is a great pity that a gifted and talented golfer like Joshua Crane has written these articles on the grading of golf courses. They have excited much attention in Britain, and are likely to give the impression that Americans lack the adventurous spirit of the true sportsman, whereas the contrary is the case, and I may say that in an extensive tour from East to West, I have not met an American golfer of any prominence who does not whole-heartedly condemn Mr. Crane’s revolutionary views.

All of this attention made Crane something of a celebrity in the world of golf. George Girard wrote in the US Golf Illustrated:

The way of the pioneer is hard. A number of leaders in golf movements are finding this true. It has always been so, and will probably continue. Among those who find this true are… Joshua Crane of Boston … and a few others I could mention.

….Now about Joshua Crane’s troubles. Mr. Crane has worked for several years on a plan to accurately chart or rate golf courses. It is a pure labor of love. After spending the summer on the links and courses of Scotland, he gave a brief summary to The Field [sic] of London. In this summary St Andrews was twelfth [sic]. Wow! Mr. Crane’s ratings came in for less discussion than himself, at least so it seemed. Leading golf publications have had letters, editorials and articles on the subject, although none took exception when Golf Illustrated published the first article outlining the plan; in fact it looked good and interesting. When the measuring rule was applied, however, something happened and more is bound to come. It will be interesting. Mr. Crane does not seem to be worrying, as he is on his yacht off Jekyl Island probably rating Prestwick from his notes.

Where Crane went and what he did were noted regularly by golf periodicals and in the sports sections of major newspaper of the day. The US Golf Illustrated published pictures of Crane competing in senior tournaments, referring to him as a “famous golf expert and writer.” Bernard Darwin mentions Crane’s views several times, taking special note of Crane’s surprising sojourn to St Andrews in 1929. On other occasions Crane is referred to as a “well known golf authority.”[3] Crane’s scores in tournaments were reported in the sports pages of the New York Times, Boston Globe and other newspapers. The caption to a photo of the modified 13th at The Country Club in the US Golf Illustrated praised the hole as one that “approached Joshua Crane’s ideal,” deference that signals Crane’s standing at the time. An article in the US Golf Illustrated from 1933 described Crane as one of the great sportsmen of the 1920’s (others included Crane’s friends Jay Gould, Devereux Milburn and Payne Whitney). The author went on to note that:

Now…[Crane] is engaged in the rather futile attempt to prove to the Royal and Ancient of St. Andrews, using clever diagrams and arguments, – that some of the holes of the classic old courses were wrongly conceived, lacking the proper finesse and antiquated, in which contention he is undoubtedly correct.

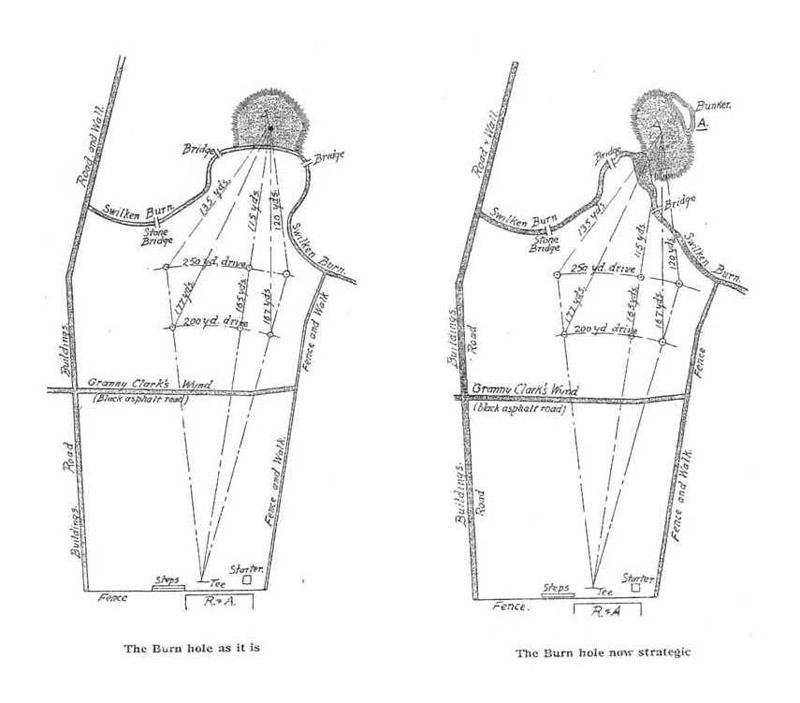

Crane published his proposed revisions to the first four holes of the Old Course the next year in the British Golf Illustrated.[4] As will be discussed later, a decade after his rankings first appeared Crane was still in full combat mode. His proposals in 1934 for changes to the Old Course make for a surprising final act to a long debate.

Crane is largely forgotten today, but during the Golden Age he was a very controversial figure. His rankings were savaged by almost everyone and Crane responded in kind. But the controversy wasn’t just over where a given course ought to be slotted in his pecking order. Reactions to Crane’s rankings were inseparable from reactions to his rating criteria and the design philosophy that underpinned those criteria. In the end it was his design philosophy that garnered the most attention and that is the reason why the debates that Crane stirred up are worth revisiting today.

A Short Life of Joshua Crane

Joshua Crane was born in 1869 into an old line and very wealthy New England family. He was a gifted athlete, playing running back for both the Harvard and MIT football teams (he received a masters in engineering from MIT). He won the United States court tennis championships four years in a row from 1901 to 1904 and participated on national track teams as a sprinter and a high jumper. He was a world class polo player and yachtsman, designing and building many of his own yachts[5]. Crane coached the Harvard football team in 1907, but was dismissed after a single season for reasons that remain unclear.[6]

Though Crane took up golf relatively late in life (Crane jokingly called it “an old man’s game”), he advanced quickly to the top rung of New England amateurs. His wealth made it possible for him to travel to tournaments in the United States, Great Britain and France. His best finish was as runner-up in the 1928 US Senior Open. Francis Ouimet beat Crane handily in the first round of the 1930 British Amateur (won by Jones in his Grand Slam year). After the drubbing he gave Crane, Ouimet joked that he might not be able to face their many mutual friends back in Boston. Crane donated what is now called the Crane Cup to Carnoustie for local amateur competitions and other cups for amateur tournaments on the French Riviera and at Dedham Polo and Golf Club, one of his clubs in Boston.[7]

The brash, outgoing Crane was a prominent figure in New York and Boston social circles, counting among his friends the most famous sons of the Gilded Age, including Jay Gould, Averill Harriman, Payne Whitney, Devereux Milburn, Harvey Firestone and John Widener[8]. These young aristocrats competed regularly in polo, tennis, yachting, squash, billiards and, of course, in golf. Befitting his social status, Crane was a member of a number of exclusive golf and polo clubs in the Boston area. Notably, Crane was also a member of the famous Conversation Club. Comprised of prominent men with a shared interest in conservative politics and golf, the club’s members included a former Canadian Prime Minister, a Nobel Peace Prize winner, a couple of US congressmen, Harvey Firestone and other important industrialists. A Yale literature professor served as the club’s recording secretary. The “King” of the club until his death in 1927, was Walter Travis.

Members of the Conversation Club wintered every year at the Bon Air Hotel in Augusta, Georgia. Their daily routine was to meet for “conversations” in the mornings and play golf in the afternoons at either Forest Hills (Donald Ross) or at one of the two Augusta Country Club courses.[9] The Bon Air Hotel was also where Bobby Jones spent his winters in the 1920’s, playing golf at the same courses in preparation for the coming summer competitions. It was at the Bon Air Hotel that Jones first met Clifford Roberts, another regular visitor and the man who would later join with Jones to found the Augusta National Golf Club. Several members of the Conversation Club went on to become founding members of Augusta National. It seems likely that Jones and Crane got to know each other during these winter visits.[10] Certainly Jones knew “King” Walter Travis. In the winter of 1924, after club members had attended an exhibition match between Jones and Arthur Havers, Jones credited Travis with giving him a putting tip that Jones believed was one of the keys to breaking his “Seven Year Drought” and eventually winning the Grand Slam.

Crane was noted for his use of an 18 inch putter that he believed helped him with the yips.[11] But more than just a good amateur golfer, Crane was also a free lance inventor, obtaining more than a dozen patents covering everything from automobile universal joints, to dry shaving machines, to carburetor parts, to men’s support socks (yes, you read that correctly).[12] Crane was a world class bridge player and in 1923 wrote A Common Sense Approach to Contract Bidding, a book that became a best seller in both Britain and the United States. As an internationally recognized expert, Crane wrote on bridge in British and American magazines for more than three decades. In 1950, the year he turned 81, Crane wrote How to Grow Old Comfortably, a collection of bromides about aging. His last book, The Impeachment of Roosevelt (A Phantasy), a novel about a fictional impeachment of Franklin Roosevelt, was published in 1953. Crane detested Roosevelt, convinced to his dying day that Roosevelt had betrayed his class and that The New Deal had caused great and irreparable harm. Crane died in 1964 at the age of 95 at his winter home in Lakewood, Florida.

Joshua Crane and his toothpick putter, 1929.

[1] As early as 1906 John Low, editor of Nesbit’s Golf Annual, conducted a vote among selected British golfers as to their favorite courses. In each year that a vote was taken, the Old Course won by a wide margin.

[2] Still intrigued by Crane’s ideas, several weeks later MacKenzie sent to Ambrose drawings of proposed changes to the 1st and 18th at the Old Course. MacKenzie’s letter (written on the boat taking him to the United States) and his sketch that accompanied it were published in Field. The proposed changes, MacKenzie noted, assumed the opening and closing holes were “found in the middle of the course.” As opening and closing holes, however, MacKenzie continued to think them to be “ideal”. A drawing of proposed changes to the 1st and 18th at the Old Course by A.C.M. Croome, also inspired by Crane’s rankings, was published in Field several months earlier.

[3] Some commentators, convinced that Crane was on to something, took the trouble of suggesting improvements to his rating system. A. J. Hills, for example, called Crane’s ratings a “splendid basis for comparison,” and in the US Golf Illustrated suggested a number of changes that Hills thought would improve the accuracy of Crane’s calculations.

[4] Only Crane’s proposed revisions to the first four holes at the Old Course were published, though he suggests in his introduction that he had completed proposed revisions to all eighteen holes.

[5] The Crane Catboat, a 15′ sailboat, is still raced today.

[6] Harvard won its first six games that year. There was talk of another national championship. But the team lost their last three games (which included losses to Princeton and Yale) to what were considered inferior squads. Accounts hint at team dissension at the end of the season. In any event, Crane was dismissed and a new head coach was hired. The new coach, Percy Haughton, ushered in what is now called the Golden Age of Harvard football.

[7] A sidebar to Crane’s competitive career was his disqualification from the 1928 Open at Sandwich for using steel-shafted clubs. While steel shafts had been approved by the USGA at that time, Crane was apparently unaware that they had not yet been approved by the R&A.

[8] John Widener is perhaps the least well known of the group. In memory of his son’s death in World War I, Widener donated funds to Harvard University to build what is now called the Widener Library, the largest private library in the world.

[9] The Augusta Country Club had both a Donald Ross course and a Seth Raynor course at the time. The Raynor course, however, did not survive the Great Depression.

[10] Given the small, elite group that gathered there, it’s hard to imagine that Jones was unaware of the kafuffle Crane had stirred up. Indeed, given Jones’ native intelligence and interest in golf architecture, it is hard to imagine that Jones and Crane didn’t talk about the issues raised in those debates which were then at their height. Jones’ writings on golf design suggest that he was both familiar with Crane’s ideas and strongly opposed to them.

[11] Crane’s “toothpick” or “vest pocket” putter received considerable attention. Crane putted with it by bending over and using only his right hand, which seemed to steady his stroke. A 1929 newspaper account of his putting noted that “his toothpick putter is not such a silly instrument as many golfers hold. He missed only one putt he should have sunk and holed two long putts, including a thirty footer that flabbergasted his opponent.”

[12] I can’t resist noting the sensation caused by the discovery in 1926 of runic letters carved in a rock on No Man’s Island off the coast of Chilmark, Maine, an island owned by Crane. The carvings were first believed to be evidence that Leif Eriksson had preceded Columbus as the first European to reach North America. Later research determined that the carvings were probably a hoax. There was no evidence that Crane was involved in the hoax. In fact he pleaded from the beginning that no conclusions should be drawn until there had been a full investigation. Nonetheless the carvings on Crane’s island are still referenced now and again by historians trying to establish that Eriksson was the first to make landfall in North America.

Joshua Crane In The Golden Age, Part II

by Bob Crosby

Crane’s Design Philosophy

Golf course rankings are a commonplace these days. Every magazine seems to have its own, each with its own rating criteria. But whatever their differences, all modern systems give considerable leeway to raters’ personal preferences. Such flexibility serves a number of useful functions, including assuring that rankings are as neutral as possible as between different styles of architecture. Crane’s “objective” ranking system, however, was anything but neutral. He baked into his rating methodology specific design preferences. That methodology had two main goals – first, to unmask the “prejudices” and “subjectivity” that had plagued golf architecture theretofore, and, second, to provide a roadmap for how courses should be modernized and improved.

Crane made no bones about these goals, writing in 1924:

At first thought it seemed impossible to put a mathematical value on such a heterogeneous mass of elements [of a golf course], many of which apparently have no relation to each other, but on analysis into its basic elements, and by proper balancing of the relative value of these elements, a result was obtained which gives an extraordinarily fair measure of comparative excellence. After the method had been worked out to a successful conclusion, it was found that the value of the tables in giving the comparative rating of two or more courses was greatly overshadowed by the fact that they furnished an accurate and graphic method of exposing the weak point of any particular course, thus making it simple for a golf architect to record his criticisms and suggestions for future use for both himself and the green committee of that particular club. Thus, by marking the weak elements on the chart with a red pencil, he could place a graphic criticism and a permanent record before the green committee as a goal towards which it might work.

After making the required measurements and applying his weighting formulae, Crane believed he had “furnished an accurate and graphic method of exposing the weak point of any particular course.” In other words, after a “scientific” assessment, the specific things that needed improving (that is, things that would make certain features more “ideal” under his system) would jump off his spreadsheets, ready to be “recorded” by the architect and then installed by the green committee. It was just a matter of collecting the data.[1]

Crane used his ratings in exactly that way. Specific proposals for improving a hole were derived from the deficiencies uncovered by his rating of that hole. His rating of a hole was, in effect, a short hand description of changes required to bring the hole closer to Crane’s “ideal”. For example, his rating of the 16th at Pine Valley proposed lowering the mid-body ridge to make the green visible from the tee, removing trees, and installing a diagonal bunker across the front of the green to provide more “control” for the approach shot, all for the purpose of making it a hole that would come closer to a 100% rating. For the 5th at Myopia Hunt Crane’s proposed improvements included:

…adding twenty yards to the second shot to encourage carry of the bunker to the left, shortening the bunker slightly giving nearly two thirds of the fairway to the right, and enlarging the further (sic) bunker on the right so that the right hand end is a little nearer the tee and the left hand projects half way across the fairway to control the long driver a bit more. Then the fair but severe rough on the left substituted for the present bushes, and mounds and swamp on the right by sand dunes and bunkers, a … hole will be ensured …which will force both control and length if par is to be secured.

These proposed “improvements” were, in essence, the application of Crane’s larger reformist program to specific features of a given hole. His rankings were the business end of the big stick with which Crane wanted to push golf design into a new and better era. Much as modern discoveries in chemistry had overthrown antiquated beliefs in alchemy, so a “calm scientific investigation” of specific courses would overthrow older “superstitions” that had plagued golf architecture and propped up the reputations of many older links courses. Crane saw himself as bringing the sweet light of reason to a hidebound golf establishment:

The popularity of golf and consequently the real charm is due to the improvement of its clubs, longer balls, better tees, better fairways fairer rough, better control, better greens. Who would want to go back to balls which could only be driven one hundred yards? The thrill would be gone. Who would want to play on courses as they were fifty years ago? Is the beauty of a property laid out on a hole, with green turf and white sand, a detriment to our enjoyment of the open spaces and lovely surroundings? Do we want to play a wide open expanse of lawn-like country, with no punishments for wild shots?

No. The standard of play is improving because the punishment for poor play is becoming universally fairer. Why do good billiard players insist on a perfect table and balls and even constant temperature?

Why do tennis players insist on tight rackets, uniform balls and level courts?

Why do polo players insist on a new ball every few minutes and on having the field as well rolled and smooth as possible?

Because the better player usually wins, no matter what the conditions and implements (a very common argument of those insisting that a large amount of luck is necessary for pleasure in golf), the real pleasure lies in the manipulation of these implements in a skillful and thoughtful way, and under conditions where victory or defeat is due to superior or inferior handling, not to good or bad luck beyond either player’s control.

No! Golf course development is on the right track, and those who take the other attitude are already finding themselves side-tracked by their own ignorance and lack of comprehension of the demands of human nature for fair play.

Crane’s aim was not merely to make courses more difficult. He was not the clownish “penologist” sometimes depicted by his critics. Rather Crane was a crusader for “fair play.” Though hazards should be robust, the punishments they inflict should be “proportional,” by which he meant punishments ought to be commensurate with the degree of the missed shot. Crane objected, for example, to the wall along the right side of the 16th at the Old Course. Its proximity to the fairway centerline meant that even minor misses to that side would suffer draconian consequences. Crane had similar reservations about water hazards. Trees were likewise a disfavored type of “control” for Crane. They might block one player but leave others with clear approaches to the green, thus failing to punish similarly shots that were similarly missed. Trees also caused uneven turf conditions, creating inconsistent playing conditions and thereby giving luck too big a role in competitive outcomes. Particularly problematical were blind shots. A well designed hole should unambiguously signal the consequences of a good or bad play and blind shots, by definition, failed to provide such signals.

For Crane there were consequences for courses that didn’t live up to his edicts. When luck or fluke interfered with competitive results, the problem wasn’t just “unfairness.” The problem was that golf’s claim to being a sport was put at risk. The issue was exemplified for Crane by an incident during the final match of the 1911 U.S. Amateur.

It is impossible not to wonder if Herreshoff and his friends felt that [luck was an acceptable part of things] when Hilton on the thirty-seventh hole in the finals at Apawamis, having sliced his approach thirty or forty yards off the green, strikes a rock and bounds onto the green, thereby winning the U.S. championship. The true sportsman deplores such happenings, and happily the modern architect is striving to eliminate these rawnesses (sic).

“Unfair” results caused by “rawnesses” or fluky, badly conditioned features were a particular problem on links courses with their irregular swales, dunes, blow-outs, hidden hazards and inconsistent turf. To the extent these irregularities had a bearing on competitive outcomes, to that extent a course was deficient. Crane suggested that those deficiencies had dire consequences. They risked turning the true sportsman against the golf, disgusted by the game’s “inequities.”

The point of Crane’s rating system was to measure how well a course stacked up against a set of ideals rooted in notions of competitive equity. Those ideals might be summarized as control, predictability and proportionality (hereafter referred to as the “CP&P” principles). For Crane the quality of a golf course was a function of how well it tested each shot (the “C”)[2], the predictability of good or bad outcomes and the proportionality of the penalties imposed (the “P&P”).[3] By contrast, generous playing corridors that failed to control shots; irregular or severe contours, blind shots and inconsistent turf conditions were markers of bad or negligent design. Tellingly, such features virtually define historic links courses. And that is exactly what Crane’s rankings tell us. The least links-like courses or links courses that had been remodeled in ways that Crane thought matched up best with his ideas (e.g. Muirfield, Gleneagles) tended to get the highest marks. Regarding the recently remodeled Muirfield Crane wrote:

For many years the natural disinclination to make changes in the historic courses was strong enough to combat successfully the revolutionaries who desired such changes, but, unlike at St Andrews, about three years ago reason prevailed, and the results of the remodeling have entirely justified the position the taken by them.[4]

Conversely, the Old Course, Prestwick and N. Berwick, among the oldest, least modified and more traditionally links-like courses, tended to get lower marks.

Crane’s analysis of golf course design raised questions that went to the very heart of things. He forced a re-examination of what – at bottom – golf architecture is about by asking hard questions about what – at bottom – the game of golf was about. Should, as Crane claimed, golf architecture be reduced in the name of “fair play” to the factors embodied in his CP&P principles, factors that had universal application to all sports and their venues? Or was there something unique about golf and golf courses? Those are all big questions. Indeed, they don’t get much bigger for a golf architect.[5]

The Debate Over Crane’s Design Philosophy

From the beginning the controversy over Crane’s rankings was less about where he ranked a given course and more about the design philosophy that underlay his rating criteria. Just a week after Crane’s first essay appeared in Field in the spring of 1924, A.C.M. Croome[6], the magazine’s anonymous golf editor, responded that that “the second hole at St. Andrews comes poorly out of the comparison with Mr. Crane’s selected holes, which suggests that there is something wrong somewhere.”[7] That is, if the second at the Old Course is rated as a poor hole, the problem isn’t that it ought to be rated higher, the problem is that the rating system is flawed.

Over the next several years Crane and Croome debated Crane’s rating criteria in Field[8], with Croome countering many of Cranes pieces either concurrently with or soon after their publication. Croome was especially concerned with the emphasis Crane placed on equity in golf design. He worried that the significance Crane gave to it would drain away the “spirit” of the game. For those reasons Croome objected to Crane’s suggestions that “control” could be achieved by way of additional rough and thought Crane’s concerns about visibility and predictability were over the top. Echoing Tom Simpson’s comments elsewhere, Croome put forth the notion that any course that did not require multiple plays to be understood was, by definition, an uninteresting course. That is, if local knowledge didn’t matter, a course was likely to be a quite dull affair. Crane responded directly to many of these criticisms, at one point publishing in Field a lengthy letter addressing some of Croome’s main concerns.

But responses to Crane in Field involved more than Croome’s criticisms. As if concerned that Crane’s ideas were threatening to fill a void in design concepts, Croome (or possibly Tom Simpson) authored a seven part series on bunkers. Crane is not mentioned by name in the series, but the timing, content and the strawmen of the pieces suggest that Crane was an inspiration. The Field chronology at the end of this essay provides some of the flavor of that bunker series.

More significantly Crane inspired a series of twenty articles in Field on ideal holes. Charles Ambrose was assigned “to further search for the truth” about design issues raised by Crane through the selection of “eighteen holes of modern construction which shall make up what [Ambrose] considers the ideal round…It is reasonable to expect that Mr. Ambrose’s articles, complementary to those of Mr. Crane, will assist materially to secure the object sought.” Regarding Ambrose’s project, Croome commented:

The article in which Mr. Joshua Crane has proposed a set of formulae by which existing golf courses may be examined and their respective merits assessed, have been the cause of widespread and occasionally heated discussion. They produced startling results when applied to a baker’s dozen of the more famous greens in Scotland and England. But none, even of those who differed most violently from Mr. Crane’s conclusions, has dared to accuse him of prejudice, or any other misleading sentiment, or to impugn the inexorable logic with which he argues from his premises to his conclusions….To further the search for truth we have invited Mr. Charles Ambrose to select eighteen holes of modern construction which shall make up what he considers the ideal round, and by means of diagrams, drawings and letterpress to give reasons for his choice. It is reasonable to expect that Mr. Ambrose’s articles, complementary to those of Mr. Crane, will assist materially to secure the object sought.

….We anticipated that when asked to select eighteen choice holes [Ambrose] would go to St. Andrews and Westward Ho! for most of his material, with excursions to such places as Prestwick, Hoylake, North Berwick and Rye. But with remarkable acumen he has observed that on seaside links the planner of a golf course must follow the lines indicated by Nature, and has comparatively little scope for expressing his artistic individuality. He has, therefore, limited his field of choice to the holes of artificial construction on inland courses. Incidentally this self-denying ordinance carries with it the suggestion that Mr. Crane may have erred in applying to seaside golf criteria which are fully applicable only to the game as played inland.

Ambrose discussed eighteen “ideal” inland holes designed by Colt, Fowler, Simpson, Abercromby and Croome, limiting himself to inland holes because “Mr. Crane may have erred in applying to seaside golf criteria which are fully applicable only to the game as it is played inland.”[9]

The responses to Crane’s design ideas in the United States were equally pointed. MacKenzie in “Pleasurable Golf Courses”[10] noted that Crane’s design philosophy harkened back to “a similar mentality to that which in Britain gave us Tom Dunn’s and other dreary courses…” Contrary to these “dreary” Victorian courses, MacKenzie pointed out that golf courses ought to give pleasure, that they ought to be playable by all classes of players, and that the game ought to be approached in the spirit of adventure and not merely as a competition. These objections echoed objections MacKenzie had made about Victorian designs seven years earlier in his book Golf Architecture. Nor were they very original. Harry Colt, John Low and others had been making similar arguments for a decade or so.[11]

Crane fired back in “Log Rolling,” accusing MacKenzie of making ad hominem attacks[12] and, even worse:

…[making] a rush to the defense of indefensible architecture, the more indefensible the more violent and illogical the defense.

Crane wanted to dismiss MacKenzie’s objections as nothing more than sour grapes over the low rating given to the Old Course:

Not a word of careful criticism, not a line devoted to showing where the detailed analysis of any hole which rates low was weak, but a violent protest against the result, in articles which are full of generalities, quotations from golf writers and poets, truisms and axioms.

MacKenzie would have none of it. His concern was not with Crane’s rankings but with the theory of golf design that underpinned those rankings. In a letter responding to Crane’s “Log Rolling” article,[13] MacKenzie made the nature of their differences clear:

As Mr. Bernard Darwin says in regard to Mr. Joshua Crane, “His ideas differ so fundamentally from ours that discussion is hopeless.” Why criticize the details regarding his individual holes when according to our ideas his fundamental principles are wrong and entirely opposed to our conception of golf?

MacKenzie’s run-in with Crane was not soon forgotten. Several years later in The Spirit of St. Andrews MacKenzie recounts meeting with Crane and Max Behr at St. Andrews in the summer of 1929. After reviewing their philosophical differences, MacKenzie reconstructed what appears to have been an actual conversation.[14] If MacKenzie’s account is anything like an accurate transcription, the two men seemed to talk past each other. Crane continued to express his concerns with competitive equity and MacKenzie continued to see Crane as a stand-in for older, Victorian ideas, with the result that their conversation doesn’t advance things very much.

If MacKenzie seems to have missed much of what Crane was about, Max Behr didn’t. Behr proved to be Crane’s most interesting and determined opponent. From the beginning Behr saw Crane’s course rankings as a Trojan Horse. The real issue was a very troubling design philosophy hidden in its belly and it was that design philosophy that Behr focused on and over which he and Crane did battle. That debate amounted to hand-to-hand combat in letters and articles, most of them published in 1926 and early 1927, in Country Club/Pacific Golf & Motor, a California golf and travel magazine. Their exchanges remain one of the most remarkable, but perhaps one of the least known, in the history of golf architecture.

A Short Life of Max Behr

Max Behr was born in 1884 in Brooklyn Heights, New York, the oldest son of Herman Behr, founder of Herman Behr & Co., an abrasives and paint company (the paint company has changed ownership many times, but still bears the family name). Herman Behr was an avid pioneer golfer and played in many tournaments with his eldest son Max. Max went on to Yale College and played on the golf team, competing against future golf architects H. Chandler Egan at Harvard and William Langford at Princeton.[15] His coach at Yale was Robert Pryde, a Scot and early golf architect in New England. Like Crane, Behr was a gifted athlete and competed in multiple sports. Also like Crane, Behr was best known during his undergraduate days for his exploits in sports other than golf. He was a star hockey player (newspaper reports suggest that Behr was the best player on the Yale team) and played as well on Yale’s football and tennis teams.

After college Behr moved to New York City to sell the cutting edge technology of the day – typewriters. In 1906 he married Evelyn Schley, the daughter of a prominent New York financier.[16] Behr compiled an impressive record in numerous amateur events after Yale, losing to Arthur Travers in the finals in the 1908 US Amateur and winning the New Jersey Amateur in 1909 and 1910, after finishing second to Travers several times. Behr seems to have taken an ownership interest in and became the editor of the US Golf Illustrated in 1914, the preeminent golf periodical in America at the time. Devastated by his wife’s death from the Spanish influenza in 1919, Behr sold his interest in Golf Illustrated and moved to California, setting up shop in Pasadena as a golf architect. He spent the rest of his life in California.

Behr did not design a large number of courses, but several were (and remain) highly regarded. In The Spirit of St Andrews MacKenzie called Behr’s Lakeside Golf Club[17] one of the best in courses in the world. Bobby Jones was a friend and most of his famous instructional shorts were filmed at Lakeside in 1931, films that give tantalizing glimpses of the original course. Behr also designed Rancho Santa Fe Country Club in San Diego, the original host course for Bing Crosby’s pro-am celebrity clambake. Behr seemed to have an unquenchable appetite for difficult causes and took up many during his life. He battled the R&A and the USGA on a number of rules issues. In the early 1920’s Behr and John Low had a series of exchanges in Field about the lost ball rule in match play. He adamantly opposed the rubber core ball. Together with MacKenzie and Bobby Jones, Behr urged a return to the gutty after Jones’s shocking sub par winning score at the 1927 Open at the Old Course.

Max Behr during the construction of Rancho Santa Fe.

Behr later advocated the “floater” ball. In articles, letters and by direct appeal, he campaigned for its adoption by the USGA. Behr was not just an armchair critic, however. He played with a floater in tournaments. In the 1929 British Amateur Behr’s use of a floater was noted for ceding to his opponents a considerable distance advantage. (He lost in the second round.) After others had given up the fight, Behr pressed on with a formal resolution to the USGA that he presented at its 1937 annual meeting. Behr wrote that the rubber core ball had rendered golf a test of “brawn rather than of skill” and that an imbalance existed between the technology of the game and the courses on which it was played. It is a recurring theme in Behr’s writing.

Behr wrote for both the US and British versions of Golf Illustrated on a range of topics, including handicaps, golf design, rules, equipment and the golf swing. He contributed articles to the USGA Green Section Bulletin and regional periodicals based in California. His social milieu in California was an interesting one. Lakeside was Behr’s home course. It’s membership was a volatile brew of movie stars, local politicians and hustlers, including the notorious renegade John Montague. Behr was arrested in 1924 for punching a Hollywood writer at a party at the home of Mary Miles Minter, then one of the major stars of the silent screen. Like George Thomas, another golf architect who had emigrated to California from back East, Behr cultivated roses and his hybrids were honored in national shows. Behr advocated a religion that took complicated relationships between numbers as evidence of divine providence. In the late 1940’s and early 1950’s he wrote opinion pieces for the Los Angeles Times and other newspapers, taking a hard line against communists, their fellow travelers (for Behr that usually meant Democratic politicians) and lamenting the decline of America. Ironically Behr, MacKenzie and Crane all held similar, hardcore conservative political views. Behr died in California in 1955 at the age of 71.

[1] The relegation of the architect’s duties to that of a “recorder” in Crane’s scheme did not go down well with architects at the time.

[2] Philosophers in the room will have noted Crane’s reductio problem here. Given the emphasis on controlling individual shots, the concept of a “hole” was largely superfluous for Crane. Indeed Crane explicitly down-played the significance of holes as a framework for his analysis of courses. A framework based on holes, Crane believed, allowed “old shibboleths” to fog the analysis. How the design of a hole linked one shot to the next was not of great significance in his system. Much more significant was how individual architectural features tested individual shots viewed in isolation. Analyzing things in terms of “holes” got in the way of that metric. A golf course for Crane was not a set of 18 holes but a series of discrete tests of golfing skills.

But if what really matters is testing golfing skills, there are better places to conduct such tests than on a golf course. One might, for example, line-off a field and set up hitting stations. If testing shot-making skills is the main point, measurements on such set-ups would be more precise, variables such as turf, trees, blindness and out of bounds could be easily controlled and so forth. It is an absurd idea, but given Crane’s design criteria it is a reductio ad absurdum against which he has no principled defense. Indeed, such testing fields ought to rate 100% under Crane’s “design and layout” criteria. Arguably, any theory of design or any tournament set-up philosophy with a similar emphasis on shot-testing has the same reductio problem. If shot testing is your main design goal, then a golf course is, strictly speaking, unnecessary to achieve your goals.

[3] The CP&P principle served another important function. They were the hidden premise in Crane’s claim that his course rankings were “objective.” Crane broke down each hole into its discrete, measurable features. Bunker and green dimensions, fairway widths, turf conditions, the proximity of water and out of bounds and so forth, were all precisely measured. This “objective” data was then rated against the CP&P standards, standards that Crane believed to be self evidently true and beyond debate. Thus the payoff from applying his “neutral” CP&P criteria to an “objective” data base was ratings expressed in neutral, mathematical terms that be used as the common denominator for ranking different courses on an apples-to-apples basis.

[4] Simpson disliked Colt’s changes to Muirfield for the same reasons that Crane liked them. Simpson called Colt’s changes, “featureless, by reason of their OBVIOUS and STRAIGHTFORWARD character… Now in Golf Course Design, the obvious thing is almost invariably the wrong thing”… Simpson went on to say the holes in question had a “complete lack of subtlety…”

[5] Such ideas have fairly ominous implications for the profession of golf architecture. If the principal design objectives in building a golf course are reducible to basic design objectives applicable to all sporting venues, the role of the golf architect will have been effectively marginalized. If there is little that is unique about golf architecture, then there is little that is unique about the skills required to be a golf architect.

[6] Max Behr identified Croome as the anonymous Field golf editor. Much of what Croome purportedly wrote, however, echoes ideas expressed by Tom Simpson elsewhere. Croome and Simpson were friends and seemed to have had similar views about golf architecture. But more than just friends, they were also at the time partners in the architecture firm of Fowler, Simpson, Croome & Abercromby. It’s not much of a stretch to think that Simpson might have had a hand in the responses to Crane.

[7] Croome is fronting-running Crane here. He seems to have had in hand the text of Crane’s analysis of the Old Course more than a year before it actually appeared in the magazine. The same thing occurred several months later with Hoylake.

[8] Because access to Field is difficult, appended to the end of this essay is a time line of the exchanges between Crane, Croome, Ambrose and others in Field over the periods in which the above discussions occurred.

[9] The series is interesting not just as a push back against Crane, but also because it gives detailed descriptions of a number of highly regarded holes in Britain that no longer exist.

[10] MacKenzie makes the distinction in this essay between Crane’s “penal architecture” and his own favored “strategic architecture,” a distinction he makes here for the first time in print. Crane accused MacKenzie of stealing the distinction from Max Behr, which is probably right. In fact MacKenzie “borrowed” a number of ideas from Behr, many of which he acknowledged in The Spirit of St. Andrews; some of which he didn’t.

[11] As far back as John Low’s Concerning Golf, proponents of strategic architecture saw themselves as being surrounded by incomprehension or even outright hostility. Low, Harry Colt, Tom Simpson and others, when making the case for the superiority of strategic designs, all take on a remarkably adversarial tone. Their writings are less expository than they are argumentative, usually aimed at the designers of older Victorian courses. That was, essentially, the fight that MacKenzie saw himself in 1920 at the time he wrote Golf Architecture. He was still fighting the fight against the Victorians in The Spirit of St. Andrew and, somewhat inappropriately, against Crane as well.

[12] Not without some justification, Crane thought everyone was out to get him.

[13] The same letter suggests another reason why MacKenzie was so troubled by Crane. MacKenzie believed that Crane’s views represented those of the “majority of golfers”:

It can be pointed out…that where Mr. Crane’s views (and the majority of golfers, until they have learned from experience, have similar views to those of Mr. Crane) have been introduced, golf courses turn out a failure. But on the other hand, wherever ideas largely opposed to those of Mr. Crane have been introduced, the courses have turned out a success.

[14] The full text of the reconstructed conversation goes as follows:

“Tell us, Joshua, how is it you took a house at St. Andrews after rating it the worst of all championship courses. You admit you love St. Andrews.” Joshua, replying in a tone which suggests that his system of rating is similar to the Laws of the Medes and Persians: “Well, it comes out last in my rating.”

“Then that simply proves that your rating is wrong, and we suggest to you that if you turn your list of ‘order of merit’ upside down you will be right. Let us analyze your system. You give so many marks for rough; we suggest that this be reversed and that it should read ‘absence of rough.’ Golfers pay for pleasure and surely they should not be subjected to the annoyance and irritation of searching for lost balls. It is no fun looking for your own ball and even less searching for your opponent’s.” Joshua, somewhat haughtily: “But do you suggest that a hole should be played with a putter?”

“That is precisely what we do suggest. No hole can be considered perfect unless it can be played with a putter.” Joshua, a bit puzzled: “Why?”

“Everyone should be allowed to enjoy a golf game, including even old gentlemen of ninety, and children of five or six. Some of them cannot drive further than a good player armed with a putter. Moreover, a stretch of rough extending a hundred yards from the tee is of no earthly interest to a scratch man but may be intensely irritating to a beginner.” Joshua: “Do you then consider it fair that two men should five perfect balls and one of them should have to play from a hanging lie and the other from a level stance?”

“We do. We consider it absolutely fair and we believe that one of the great charms of the British championship courses that you admire so much is these undulating fairways. They simply differentiate between a first class player like yourself, who is able to play from a hanging lie, and others, like ourselves, who are not so skillful. Apparent luck of this kind is always, in the long run, to the advantage of the first class player.”

[15] Chandler Egan was also an excellent hockey player and the two probably met regularly in the rink in the winter months. Behr just missed competing against Hugh Wilson who graduated from Princeton the year before Behr arrived at Yale.

[16] As a wedding present Evelyn’s father gave the couple a summer home in Far Hills, New Jersey, a faux rustic house ingeniously built to straddle a creek. The odd, brooding residence remains largely unchanged, located near the main entrance to the U.S.G.A. headquarters in Far Hills.

[17] Presaging Augusta National, a number of commentators at the time thought Lakeside was a revolutionary design because of its very wide fairways, minimal rough and paucity of bunkers.

Joshua Crane In The Golden Age, Part III

by Bob Crosby

The Behr – Crane Debate

Behr grasped more clearly than most the significance of how Crane had framed the debate. As will be recalled, Crane had given to his CP&P principles a central role in his analysis of golf design. His justification for that role was that those or similar principles were the keys to equitable sporting competitions generally and, as such, should also apply to the design of golf courses (mutatis mutandi). It was a simple and highly intuitive proposition. After all, Crane asked, golf claims to be a sport doesn’t it? That was at the heart of Crane’s rationale for making his CP&P principles the relevant metric in assessing the quality of a golf course. Only a course that “controlled” shots (the “C”), made playing outcomes predictable (the “P”) and had hazards that penalized misses proportionately (the other “P”), only those kinds of courses would pass Crane’s muster.

Trying to rebut Crane’s views by asserting that he failed to take into account a course’s strategic opportunities, the fun of playing it or its naturalism (the tact taken by MacKenzie and others), missed the mark against Crane. Such arguments didn’t advance things because they didn’t reach what was most important to Crane – that equitable considerations so central to other sports should play a similarly central role in the design of golf’s playing venues. That was the high ground Crane had staked out. Even if a course were strategic, fun and natural, it did not necessarily advance the goals that mattered most to Crane. What was needed against Crane were reasons to think that his most important goals were misguided. What was needed were reasons to think that the CP&P principles (whatever their internal logic) should not be given pride of place in golf architecture.

That was how Behr saw the challenge presented by Crane. Behr understood that the issue was, at bottom, whether the most basic principles in golf design were reducible to equitable considerations that applied to competitive sports generally (again, mutatis mutandi). Which put Behr in a difficult spot. Unless Behr could rebut Crane’s case for a tight link between golf and other sports, neither Behr nor anyone else had a principled basis for objecting to the types of courses that would result from implementing Crane’s CP&P principles. That forced Behr to make what appears at first blush to be a very odd claim. To undercut Crane’s justification for the centrality of his CP&P principles in golf architecture, Behr had to make the case that golf was not a competitive sport like others. Behr had to make the case that golf was in important respects sui generis; [1] he had to argue that golf was unique and fundamentally different from other sports. That was the basis of Behr’s challenge to Crane’s idea that the CP&P principles ought to be the benchmark of good golf design.

Behr’s case for golf’s sui generis status turned on a contrast he drew between “games” such a tennis, football and billiards and “sports” such as hunting, mountaineering and golf. How Behr made that distinction will be discussed in more detail below, but for the moment it should be noted that the two types of pastimes represented for Behr two fundamentally different kinds of human activity that called for fundamentally different kinds of venues and competitive psychologies. Playing, say, tennis and playing golf were for Behr qualitatively and irreducibly different sorts of things and for that reason their respective playing venues should follow qualitatively different design principles. If the CP&P principles made sense in the context of “games” such as tennis, they did not make sense in the context of “sports” such as golf.

Behr’s game v. sport distinction is often dismissed these days as a bizarre fuss over semantics or, worse, as a sign that Behr had a screw loose. But that is to misread badly what was going on. It is a recurring theme in much of what Behr wrote because it did important work for him.[2] In debates with Crane, Behr used the distinction to attack Crane’s crusade to align golf more closely with other sports. As noted, the point of the distinction was to discredit the notion that golf courses would be improved if the CP&P principles played a larger role in their design.[3] But more was involved than just rebutting Crane. The point of Behr’s battle with Crane was not just to dislodge the central role Crane assigned to his CP&P principles. It was also to give a central role to a very different set of design principles.

* * *

Behr and Crane banged heads over these and other issues in 1926 and early 1927 in a series of point-counterpoint articles the pages of The Country Club & Pacific Golf & Motor. There Behr set out different formulations of his view that golf was more like a “sport” such as hunting and fundamentally unlike a “game” such as tennis. Behr noted in one formulation that:

…[G]olf is not a game. It is a sport. And the very essence of a sport lies in the suspense between the commencement of an action and the knowledge of its result. The courses of the Penal School deny this. The golfer has merely to place his ball within the bounds of the fairway. Thus the expert, because his ball rarely strays, can anticipate knowledge. And the inexpert knows in short order whether his ball is safe or not…This is the status the Penal School has reduced golf to.

In another context, Behr draws the distinction slightly differently:

In a game the contest is for control of a common ball. Skill is opposed to skill, and hence is relative to the tasks which the opposition creates. But in all sports skill is expressed along parallel lines. That is to say, in sports there is a conceivably ideal way in which the task of skill might be accomplished by all contestants. We are conscious of this in the playing of a golf hole, and according to our abilities, we succeed or fail in paralleling this line. Thus golf belongs within the category of a sport. And in sport skill is comparative in solving similar problems. The actual opponent is golf is nature, the human opponent being merely a psychological hazard….

Two ideas inform Behr’s different formulations of the distinction. First, a golfer playing on a well designed courses, like a hunter or a mountain climber, is engaged in overcoming natural obstacles. His primary opponent is “nature” (whether actual or made to appear so by an architect):

…when one attempts a great carry, or to direct one’s ball adjacent to danger to reap an advantage, one cannot anticipate what the result of one’s efforts to be. There is suspense during the period one is making up one’s mind just how much to go out for. There is suspense during the flight of the ball; and suspense ends only when it comes to rest… And if one is playing upon links land, the nature of the [ball’s] lie is also a mystery. And then again a decision must be made. And to gladden the heart of the true sportsman this period of suspense is sometimes lengthened by a blind shot.

Behr expresses this idea elsewhere:

…the unknown element in golf, against which the player contests, is the strategy of nature. To demand that this be a known quantity such as a billiard table, a tennis court or a polo field is a reductio ad absurdum.

For Behr a golfer’s belief that he is engaging nature is important for a number of reasons.[4] For one thing, it disrupts rational expectations about golfing outcomes. Uncertainty about outcomes means that “[golfers] can never, with all the skill in the world, fathom a sport, error is perennially with us.” Engagement with nature and its attendant deceptions, irregularities, unpredictability and even lack of visibility is what gives the “sport” of golf a “psychological” dimension that is lacking in “games.” It is what makes playing on naturalistic courses “an adventure of the spirit.” A propos Crane, Behr asks:

Is it possible then that one can compute the psychological reaction induced by a real golf hole? Must it not affect all golfers differently? Is it not, verily, its spirit reflected in him as in a looking glass? Hence may it not possibly be that the very imperfections of St. Andrews, discovered by this rational minded critic [that is, Crane], are doubtless, like those of a fascinating woman, the secret of its charm?

Behr’s “naturalism” is not about aesthetics. Whether or not a course appeals to the eye or satisfied the edicts of good landscaping were not terribly important to him. The point is that golf played on courses that appear natural transcend the limitations of a “game” by reason of the higher drama only such courses can engender. They engender that extra drama because on such courses players willingly forego rational expectations about playing outcomes and by doing so they accede to the notion that golf is an unpredictable adventure. That is, players perceive themselves as engaging nature and all the uncertainties that implies and not merely submitting to a man-made tests of their golfing skills.

If, for example, you spend an afternoon making perfect casts at a trout stream but catch no trout, you don’t complain that you were treated unfairly. A day in a dove field in which you make excellent shots but bag no dove does not elicit the response that the dove were too unpredictable. Indeed, to complain in such contexts about “fairness” is not just nonsensical, it is an egregious category mistake. Behr’s point is a similar one. If you believe you are engaging nature directly, things like unpredictability, bad luck and quirk are willingly tolerated and understood as integral to the experience. On the other hand, “rationalizing” golf design by minimizing what is “elusive or unpredictable” is to deprive golfers of that sense of an engagement with nature. Which was not a minor deficiency for Behr. To the contrary, it was nothing less than an “attack on golf itself.”

If a golfer’s perception that he was directly engaging nature was one key to the game v. sport distinction for Behr, an equally important key was the linked concepts of strategy and freedom. For Behr the satisfaction of winning a “game” with superior physical skills was merely a first order reward. Behr fundamentally disagreed with Crane’s notion that “The higher test of skill that is needed, and the greater pleasure that is afforded, in playing a golf course, certainly justify every effort that can be made to advance toward perfection.” For Behr there were higher, better satisfactions and only “sports” offered them. Those higher order satisfactions were about the successful execution of voluntarily chosen strategies, or, as Behr called it, “managing freedom.”[5] And when it came to strategic freedom, the more freedom the better:

[A golfer’s wish] is to be his own master. What he desires most of all is freedom. And freedom implies the maximum of self -discipline with a minimum of government from without. He never tires of a golf course that calls forth the spirit within him. But when he is continually made to feel the birch rod of the rough with its bunkers for every wayward shot, golf becomes an exercise of caution rather than of courage…

Why, then, should we continue to think of the purpose of hazards as being that of a direct penalty for mere ineffectual strokes? Even if by littering the course with these [P]rohibition agents…, what have we gained in terms of the spirit of golf? Have we not crushed it?

At the heart of Behr’s notion of freedom (and also at the heart of his game v. sport distinction) was that a player engages hazards as and when he elects to do so. And if hazards are engaged voluntarily, that engagement, as Behr put it, is “joyful” and “zestful” and not “compelled.” Golf is like hunting or mountaineering in the sense that the participant derives pleasure not just by exercising his physical skills, but also (and mostly) by exercising those skills in the execution of strategies of they player’s own devising against natural obstacles about which he will always have incomplete knowledge.

Behr also objected to the emphasis Crane put on proportional or graduated penalties. The issue was foundational for Crane, but it was equally foundational for Behr that equitable concerns be subordinated to others factors. The issue came to a head in their exchanges in late 1926 over the proper role of rough. Rough was one of Crane’s favored methods of “control” because Crane thought it among the most proportional and “fair”:

The popularity of golf and consequently the real charm is due to the improvement of its clubs, longer balls, better tees, better fairways, fairer rough, better control, better greens. …. Do we want to play a wide open expanse of lawn-like country, with no punishments for wild shots?

A month later Behr answered Crane’s question:

…The confinement of width of play by the rough precludes to a great extent the creating of future threats. And even where they exist, the player whose ball has found the rough has not a lie to make a direct attack upon them. He must content himself with a negative shot. And with it he either outflanks them or he plays his ball so close to them that they cease to be dangerous.

Crane responded in The County Club, noting that “I think [Behr] will agree with the writer that the true essence of a good tee short is that if it is placed properly in a certain area, it shall have the advantage of an easier second shot.” Behr countered a couple of months later, noting about rough that:

… the rough extracts punishment in the degree a player lacks skill in the mere perfection of striking the ball. But a “Bobby Jones” rarely, if ever, tops a ball, and, comparatively speaking, his ball will only rarely stray from the fairway. For whom, then, does all this trouble exist? For the poor player of course. Consequently the penal school opposes [sic] a minimum of hazard to a Jones, a Hagen or a Von Elm and a maximum of hazard to the great majority.

Behr had two problems with Crane’s affection for rough. First, rough meant that shot-making will be impaired and that impairment will dispose the architect to dilute the severity of hazards farther along on a hole. Second, any hazard whose main function was to punish mishits means by definition that it will be a bigger threat to weaker players than stronger ones. It followed that an architect who designed hazards that all players are forced to negotiate will feel a corresponding duty to assure that punishments meted out are proportional. That is, he will feel a duty to design hazards that are “fair,” as Crane might have said. Which for Behr was precisely the problem.

Behr thought proportionality was anathema to good golf design. He believed a designer should feel no obligation to make hazards proportional. As Behr put it, “the moral dimension” should have no role in golf design. Worse, he believed that there was a direct trade-off between proportionality and playing drama. It is the threat of inequitable, devastating hazards that accounts for the highest drama in the game, which for Behr the whole point of good golf architecture. Hazards ought to be nasty, brutish and, most importantly, perceived as such. And if a golfer is given the freedom to avoid them, there is no reason why they can’t be. An architect owes the player nothing in terms of equity if the player is given the option to play away from hazards. A primary pay-off of strategic freedom is the drama created by a player’s fore-knowledge that his failure to pull off an aggressive laying strategy might indeed have consequences that are devastating, disproportionate and “unfair.” For Behr that sort of “unfairness” was a marker of good architecture.

To sum up, Crane crusaded for a theory of a golf design that turned on the idea that competitions in golf ought to be more like competitions in other sports. Specifically, Crane wanted to see older, rougher links courses abandoned as models for architecture in favor of more “objective” designs – that is, designs incorporating his CP&P principles. Behr countered that other competitive sports were the wrong lens through which to see golf. Set against Crane’s notion of “control” was Behr’s notion of strategic freedom; set against Crane’s concern with well-conditioned courses that enhance “predictability,” was Behr’s notion that “natural” courses should be unpredictable and elusive; and set against Crane’s notion of “proportionality,” was Behr’s notion that equity can kill off the highest drama the game offers.

A Last Hurrah

Joshua Crane first took the stage in April of 1924 with the publication of his theory of rating golf courses. His follow-on rankings and analyses of courses in England, Scotland and the United States were extremely controversial, a controversy that reached a peak two years later in 1926, but continued thereafter at a lower boil for a number of years.[6] It seems fitting, however, that we give Crane the last word. After all, he started things.

In early 1934 Crane returned to his analysis of the Old Course, authoring a series of five articles in which he proposed “improvements” to the course’s first four holes.[7] Crane’s introduction to the series reprises much of the venom from a decade earlier, calling his opponents of his views “fanatical beyond hope of redemption,” “unbalanced” and “obsessed.” Nor was Crane above playing the victim card:

Do not think, gentle critic, that I am so besprinkled with bells that I hope that … any of these fanatics…will recede one jot or title from their cemented position, but I do hope that they will give me the credit of being sincere…

Crane went on:

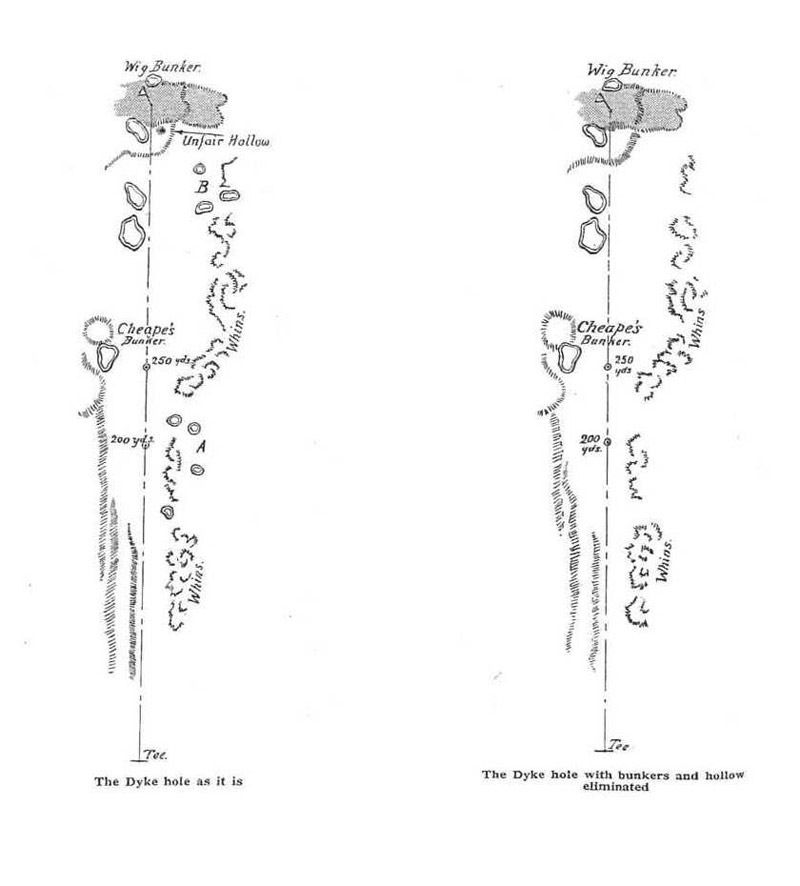

…it is surprising strange that a few of us palisaders have survived the ordeal and can still discriminate between [the Old Course’s] blessed faults and its faulty blessings, its irritating charms and its charming irritations.