The Architectural Evolution of Stanley Thompson

by Ian Andrew

May, 2007

Noted golf historian Geoff Cornish has a theory: if Stanley Thompson had been based in the United States or the United Kingdom instead of Canada, he would have received a lot more international acclaim. Cornish may have a bias – after all, he was one of Thompson’s associate designers for several key projects, including Cape Breton Highlands Links. But Cornish also has a point – though Thompson, who designed courses in Canada, the U.S., South America and the Caribbean from 1915 until his death in 1953, was well known by his peers, it is only recently that he has become part of the canon of noted golf architects. But he began his career at a time when there was little education or grounding in golf design. So how exactly did Stanley Thompson evolve to become Canada’s great golf architect, a man held in high regard by the likes of Charles Alison and Alister Mackenzie? How did he develop his style and what influences shaped him along the way?

Despite Stanley Thompson’s assertion that he was born in Scotland, he was in fact born in 1893 in the eastern part of Toronto. He was one of the famous Thompson brothers which included Nicol, Frank, Matt, and Bill. Each, including Stanley was very skilled at the game of golf and worked at one point or another in the golf industry. Stanley spent some time caddying at Toronto Golf Club.

Stanley went to Ontario Agricultural College to take some courses but ended up enlisting to join the war and served in the Canadian field artillery from 1915 till the end of the war. Stanley used every leave to play a series of links courses throughout the British Isles and the Heathlands courses around London with his brother Frank. Upon his return he promptly joined his brother Nicol Thompson, the head professional at Hamilton Golf & Country Club and George Cumming, the head professional at Toronto Golf Club in their golf design business. Their company was named Thompson Cumming and Thompson. Stanley actually worked for both of them briefly before the war while he was an undergraduate at Guelph University, but was not a partner till his return. After a very short period both Nicol and George found they needed to make a decision between their jobs as golf professionals and club makers and their business as architects. Both retreated to the stability of their clubs leaving Stanley with an incredible amount of work. He first reorganized the company as Lewis & Thompson, following an arrangement with an American construction firm, in 1921, but that was quickly dissolved. He then formed Stanley Thompson and Company the following year.

This is the 11th green at St. George’s Golf & Country Club under construction. There were

many instances in Thompson’s career where horse and man built the entire course.

The single most interesting question surrounding Thompson is how he developed his flamboyant style. Needless to say Thompson was born with talent. As Geoff Cornish, said, “Stan was a very inventive man who marched to a different drummer.” Geoff went on to comment that, “he was also very interested in everybody’s work” showing his genius was refined through reflection and careful attention to his peers. You can find the foundation for Thompson’s architecture in two major influences. H.S. Colt completed two courses, Toronto Golf Club in 1912 and Hamilton Golf & Country Club in 1914 that quickly became the benchmark for all of Canadian Golf Architecture. When one examines the routing technique of Colt, he concentrated on placing the par threes in the most dramatic natural locations and in Thompson’s work you see the same technique. This is reinforced by Bob Moote, one of his associates, when he said, “After walking the land, Stan usually chose the par three’s first and then routed the rest of the course around them. He liked to find green sites, so there wasn’t too much bulldozer work.” This is certainly true of his early work, where very little earth work was done. Thompson’s bunker work also shared a similar construction technique and style to Colt’s bunkers; although this may have been influenced by the fact the Thompson likely used the same construction teams that created Colt’s two Canadian courses. Geoff Cornish even remembers seeing a letter from Colt on one occasion, so it is likely that Stanley had taken the time to meet Colt and Geoff also commented that “He [Stanley] was a great admirer of Colt.” Certainly one can see similarities in the early work with Colt, but as Thompson progressed one began to see a change in his work, such as the green sites at Burlington that foreshadowed what was to come.

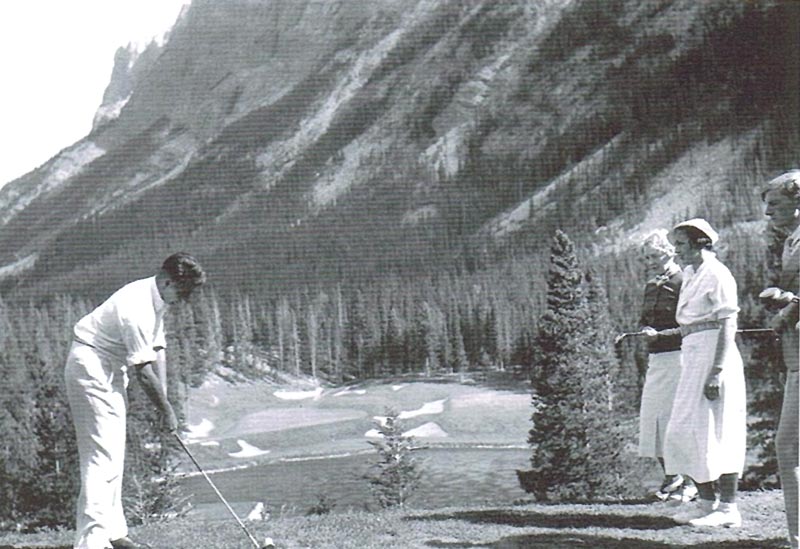

William Van Horne of the Canadian Pacific Railway came out to see Banff Springs thinking it was

finished since Thompson had all been spent the entire budget. He arrived to find a half built

course and was furious. Stanley Thompson walked him out to The Devil’s Cauldron to

share a cigar and talk about what they were creating. They returned some time later

arm in arm with Thompson having secured the additional funds.

The other great influence on Stanley Thompson must have been George Cumming. Cumming was the head professional at Toronto Golf Club from 1900 through to 1950. He was called the Dean of Canadian Golf Professionals because he was responsible for well over 30 future head professionals at other clubs including future Canadian Golf Hall of Fame members Albert and Charlie Murray. George would have been a mentor for both Nicol and Stanley Thompson. Cumming was more than just a golf professional, he was a club maker, wrote articles on turf for Canadian Golfer and one of the earliest Canadian golf course architects. He was likely selected initially to design courses because of his Scottish heritage and his place of prominence as the professional at Toronto Golf Club, but Cumming turned out to be an excellent architect in his own right designing such gems as Scarboro Golf & Country Club, Brantford Golf & Country Club and Summit Golf & Country Club. Cumming was the person Toronto Golf Club entrusted to select the new property for relocation of the club before Harry Colt made his trip to come design the course. When you take Cumming’s experience and the close relationship he had with Stanley Thompson, it would be most likely that George Cumming was the first to teach the young man how to route and build a golf course. Their routing styles are remarkably similar, with both using short holes for drama and long holes to traverse lesser land. Both sought elevated tees, raised green sites and natural plateaus. Their holes tended to run through or along valleys rather than playing directly across them. Neither designer minded a blind shot if the green site beyond was worth it.

With so much early work, Thompson likely learned a lot as he went, and many of the early architectural differences in greens and bunkers could have been the influence of construction foreman as he tried to manage the large workload. After setting out on his own, he also began building courses for other architects including Charles Alison at York Downs in 1922. It’s quite likely that Stan’s next major influence was the construction of York Downs. Cornish points out: “Alison and Stan were pretty good friends, they also both saw eye to eye on the use of the principles of art in golf course design.”

As golf really took off across Southern Ontario a series of architects such as Walter Travis, A.W. Tillinghast, Willie Park Jr., Herbert Strong and Donald Ross all worked in Toronto at various points and each had influence on Stanley Thompson. “Stan never minded about competition, but for some reason he did have it in for Tillinghast. His feelings were hurt when he didn’t get Scarboro [1926],” Cornish continued. “Stanley was very generous with his opinions of others. He loved anything impressive, but it almost put him down in the dumps at times too.” Thompson often provided the construction crews for many of those architects, and in doing so was in a position to learn theirtechnique and observing their different styles first hand. Geoff relates how many of the architects became great friends of Thompson through their visits with him and most would drop by the office for a drink when coming through town, particularly during prohibition. The origins of the ASGCA go back to this time and Stanley Thompson wanting to form an organization just like the British Golf Course Architects.

Cataraqui Golf & Country Club was done after Banff and around the time of St. George’s. It clearly

illustrates a little more restraint than the other more high profile courses of that era. Thompson

built many courses that were intentionally less elaborate and lower profile. Defining him

by Banff and Jasper is quite inaccurate to the body of his work.

As the early 1920s progressed, Thompson added more flourishes and personal style to his courses. He began to artificially raise greens and build deeper bunkers at places such as Burlington. Some of his bunkers, such as the originals at Jasper Park, began to have the islands, fingers and flashes all indicating his evolution was well under way. This was also a time when he had traveled to see many landmark projects like Winged Foot and Cypress Point under the recommendations of different architects. Geoff told me that, “he was extremely interested in other peoples work and historic courses” Stanley sought out projects by architects such as Alister Mackenzie, A.W. Tillinghast and George Thomas and their bunker styles undoubtedly had an influence on Thompson’s development as an architect. Certainly Tillinghast and Alison were not shy in their use of fingers and flashes and Thompson had a chance to watch both build their courses. Thompson even mentioned in an interview in The Saturday Evening Post about visiting Pine Valley and admiring the course, though he added he had no desire to emulate its style. Geoff makes it clear that while traveling or building in the U.S. that he saw much of his peers work. These travels may well have led to the desire to attempt more dramatic architecture.

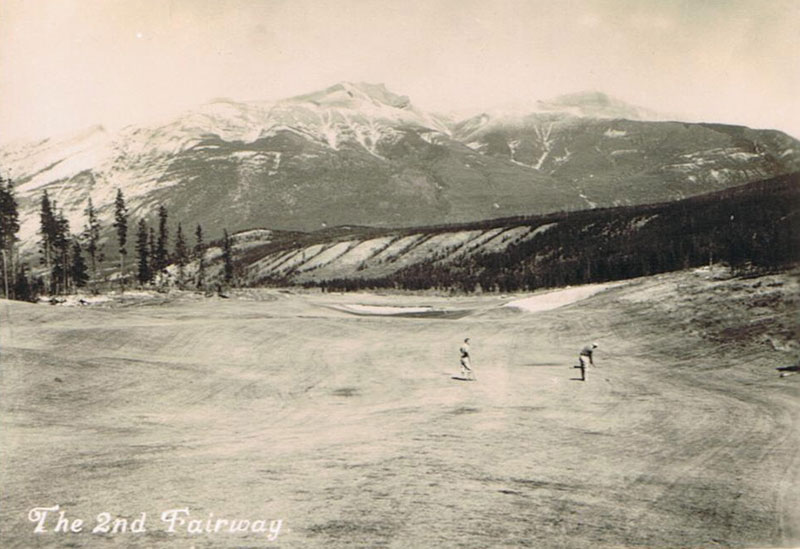

Jasper Park Lodge was done a few years before Banff. This photograph was from the opening

year shows the bunkering to be quite simple. After Banff was completed, The Canadian

National Railway (direct competition with Canadian Pacific) asked Thompson to

come back and add soil to create fingers and flashes so that the

bunkers were at least as good as Banff’s.

All of this artistic evolution comes forth in Banff Springs, one of his first true masterworks. It was a flourish of elaborate capes, bays and islands of Banff Springs that showed a progression away from the subdued early work to the style that would eventually make him famous. Geoff commented that even the mountains had an influence on his art, on train trips together he was still inspired by peaks and valleys many years later, so much so that Geoff felt the mountains themselves were likely an important influence on the bunkering and mounds at Banff. Banff’s was so remarkable that Thompson made an immediate impact, not only on Canadian golf, but golf in general. Golfers sought out this magnificent jewel surrounded by the stunning Rocky Mountains, only to be further stunned by the amazing bunkers that competed evenly with the scenery. The work and refined techniques he’d developed were so remarkable that Stanley was brought back to Jasper to add topsoil to the bunkers to create the fingering and flashes so that the bunkers were equally dramatic.

The photo of the second hole illustrates the original panoramic view out to the ocean, but unfortunately

trees have almost completely blocked this view. Thompson was very aware of including the

mountains at Jasper, the city of Vancouver at Capilano and the ocean at Cape Breton

Highland Links right into his routing. At Cape Breton tree removal will be

vital to any future restoration program.

His bunkers were not the only evolutionary aspect of his work; the routings got better, the strategies more varied, and even the look of the work changed as time progressed. Two particular courses showed his maturity when it came to routing. Cape Breton Highlands Golf Links is more than just golf; it’s a window into the region’s unique settings and geology. He takes you from the wide open highlands, to holes overlooking the ocean, through a densely forested mountain pass, a section along a major river, then heads back into the highlands and finally out to the ocean at the end. What is more remarkable is he did using only areas of the property where he could find soil since they had only one truck available to move soil or rock. Highlands was built by hand.

Capilano Golf & Country Club was all about dealing with a remarkably steep site and finding a way to get players up and down the mountain. The golf course has over 400 feet of elevation change from the 1st tee down to the 6th green. What is truly remarkable is how you get back to the clubhouse with Thompson winding the holes back and forth up a series of plateaus and benches. The holes play well, avoid excessive climbs and are surprisingly walkable. You barely notice he has you climbing back up the same 400 feet from the 9th through to the 15th because of how he runs holes diagonally up the grade.

It’s not very often you get to see a green site that is long gone. This is the old green site for the 3rd hole

at St.George’s Golf & Country Club. The par three was blind from the tee, because of a large knoll

in front of the green, leaving only Stanley’s wild and elaborate bunkers to guide you in.

The long term plan for St. George’s involves restoring this green site.

The bunkering is still the predominant feature that everyone thinks of first. Many projects, such as St. George’s Golf & Country Club 1928, Kawartha Golf & Country Club 1931 and Capilano Golf & Country Club 1937, featured very flamboyant bunkering, but what becomes interesting is others like Waterloo (now Galt), Westmount and Whirlpool were still built to a more modest bunker style. While his feature work took on more and more flamboyant turns, the backbone to his art never deviated much from his original technique of finding and using the natural contour of the site. He continued to talk in reverence about the Scottish links saying things like, “Practicing golf architecture without studying the links of Scotland is like a divinity student not reading the bible.” When building courses he always left natural contour alone, and seemed to embrace the unusual opportunities like at the 13th at Cape Breton Highlands, where the natural knoll in front of the green sets the tone for the hole. In his booklet About Courses: Their Construction and Upkeep, published in 1923, he stated “Nature must always be the architect’s model. The development of the natural features and planning the artificial work to conform to them requires a great deal of care and forethought.” Stanley is telling us that his artistry wasn’t the just creating the flashes of his sand faces, but also the way he blended the backs of his wild mounds into the native grade still achieves soft and flowing lines. When one thinks about all of Thompson’s courses, it is easy to come to the realization that all of his work flows seamlessly into the natural surroundings beyond.

This image shows the 18th at Kawartha Golf & Country Club, originally built for the employees of

General Electric during the height of the depression. This course remains today as one of

the most intact examples of his work, and one I highly recommend.

Many sources describe Thompson’s bunker placement as strategic, but I don’t completely agree. He was more likely to bunker a natural hillock than place one at a planned distance. Thompson certainly placed his share of strategic bunkers, but he also placed as many that were not really designed to come into play. It is the visual aspect of bunkering that sets Thompson apart. He saw the golf course as a visual canvas which often extended right off the site and into the scenery around him. His bunkering was used to focus the eye as much as define play. He was among a group of architects that included Thomas and Mackenzie who believed in making the strategies and hazards of the course clear for the player to see – and enjoy. Stanley here describes his bunker style, “Every now and then I get a mean streak and like to fool the boys a little. But, I never hide any danger. It’s all out there for the golfer to see and study.’

His work went from economical to extravagant and almost all the way back again. The style was certainly influenced by the world around as much as the other architects work he admired. We see the early influence of Cumming and Colt right through to the influence of his peers like Tillinghast and Thomas, and how Stanley Thompson was always learning and gaining more insight as he progressed as an architect. His work progressed to a point where he is as influential as any architect’s work that he sought out. As the Ottawa Citizen said about him in its eulogy, “Stanley Thompson has left a mark on the Canadian landscape from coast to coast. No man could ask for a more handsome set of memorials.”

The End