To spend a 36 hole day split between Mount Bruno and Montreal’s Meadowbrook is, more or less, to venture to polar opposite ends of the Canadian golf club spectrum. Mount Bruno, among other rules, still requires knee-socks with shorts and forbids visitors from posting pictures of its Willie Park Jr. designed golf course on social media; whereas at Meadowbrook, you’d imagine, pretty much anything goes, short of driving the thirty-year-old, chugging and oil-reeking golf carts onto the greens (not that that doesn’t happen quite frequently, I presume, whether maliciously or out of pure ignorance.) Although Mount Bruno’s initiation fee remains undisclosed to the public, if you tack on three zeros to the end of Meadowbrook’s standard green fee rate (40 $), you probably get within its ballpark.

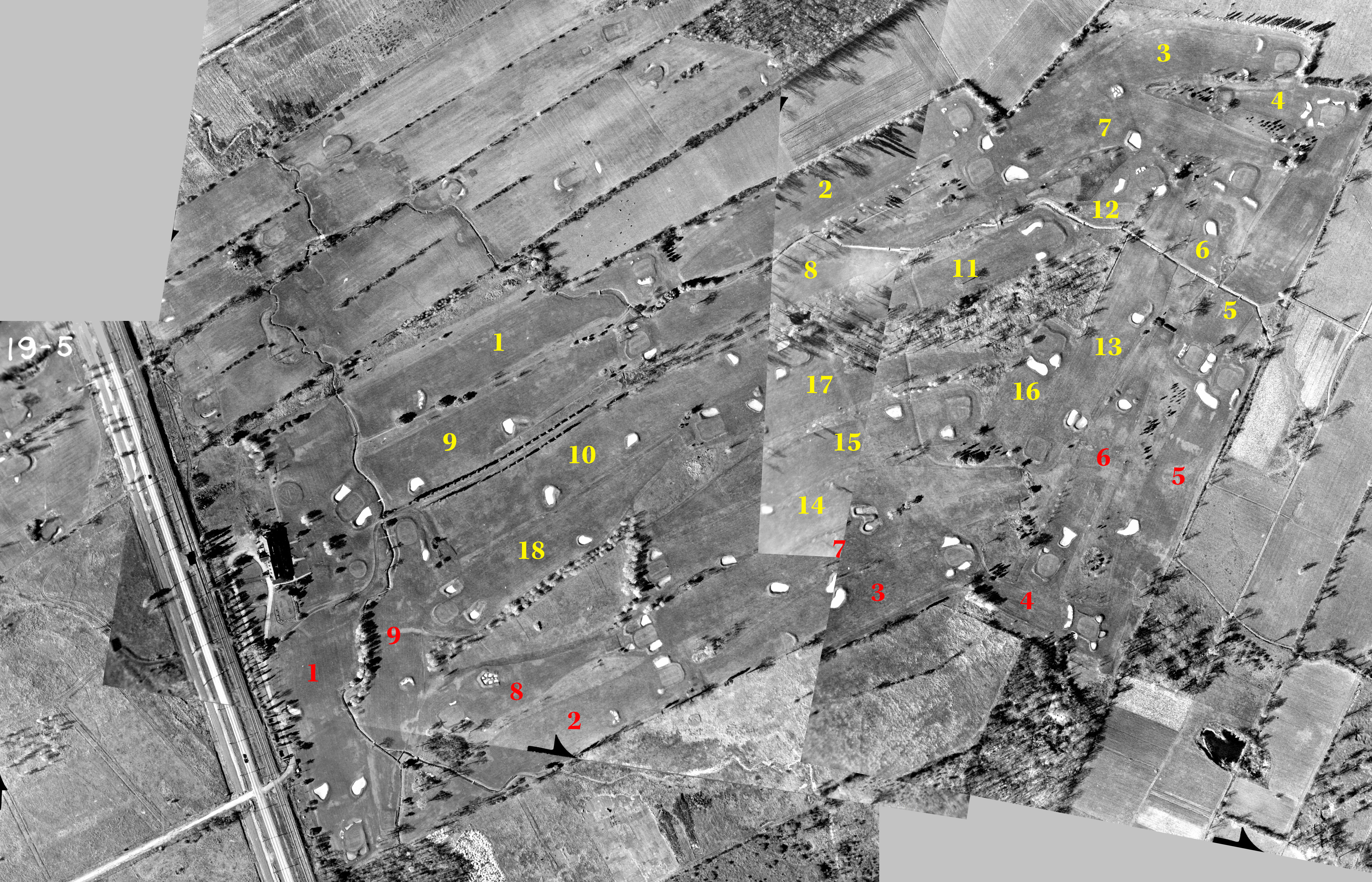

Suffice to say, then, that upon first glance, most are likely to assume that these two golf clubs have nothing in common. In fact, at least as things stand now, more than a century removed from their respective openings, that is probably the case; however, if one digs deeper and looks beyond the half-century or so of low-budget maintenance and decay accrued upon the surface layer of Meadowbrook’s golf course as currently presented, you’ll find traces of what were formerly the two golf courses belonging to the Summerlea Golf Club, to whom belonged 27 of the 63 holes that Willie Park Jr. designed in Lachine on the south-west side of Montreal Island.

62 of those 63 holes, from tee-to-green, are gone. Even the 4 greens that remain from his layouts for Summerlea, although positioned about where they were prior to 1963, when the club moved to its current location, now possess merely the faintest suggestions of anything designed by a professional architect, nevermind a man who crafted some of, if not the finest green complexes of any practitioner ever, as evidenced by a handful or so on display at Mount Bruno. Yet, despite their convex, perfectly saucer shapes, these remaining greens are cleverly perched either on ridges or set just beyond knolls so as to add natural playing interest on a property that, when compared to some of the others that Willie worked on in eastern Canada, features relatively little of it.

“No expense has been spared in the construction of the courses,” reported The Canadian Golfer in 1922, “ and Mr Willie Park, the golf architect, has personally supervised the finishing of each green, so it would be superfluous to say that they will be excellent.” Three years later, after hosting the 1925 CPGA Championship, the same publication proclaimed that “during the whole of his distinguished career he never was instrumental in constructing a links of better balance one, two, and three shot holes. Like many other Montreal courses, Summerlea, owing to the absence of rolling terrain, did not lend itself particularly to an ideal golf course, but Park, with consummate skill, took advantage of every possible natural contour.”

Founding shareholders paid an initial $400 and, in turn, they purchased a 215 arpent property abutting a yard and tracks belonging to the Canadian Pacific Railroad. A temporary office was also set up in the Board of Trade building. Upon raising sufficient funds, rather than build an opulent clubhouse, The Montreal Gazette, in 1921, noted that the “prominent Montrealers” behind the project preferred to spend on the golf course itself; and Willie, who had been around the city regularly since being hired to work at Mount Bruno in 1918, was the obvious choice to lay out of the new links.

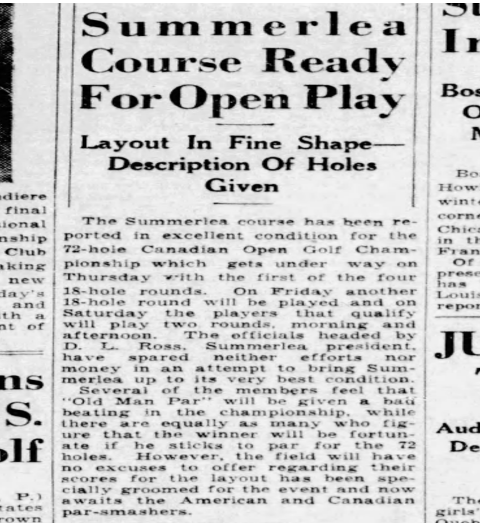

Throughout the construction period, it was reported that he made regular visits to the site, paying close attention to the greens, especially. Numerous events, both amateur and professional quickly followed suit, including 1928 Canadian Amateur and the 1935 Canadian Open won by Gene Kunes at 280 strokes, largely thanks to a course record 68 in the final round. By all accounts, the golf course made a credit of itself that week.

The good times, however, didn’t roll on. In the midst of the Second World War, the club went bankrupt, only to be saved by Senator Donat Raymond who immediately leased it back to the members. Just three years later, in 1949, he was again forced to come to the rescue following a catastrophic fire in the clubhouse; unfortunately, not even his philanthropy could save the irreplaceable artifacts and documents from the ashes.

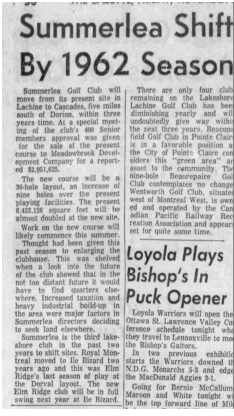

Despite a tumultuous decade, the club proceeded to host the CPGA Championship in 1950, the Quebec Amateur in 1951, and the Quebec Open in 1954. Meanwhile, outside of its private gates, the province, on the whole, was undergoing a period of unprecedented social and cultural upheaval, as it emerged from a period known as “The Great Darkness” following the defeat of the repressive, backwards Union Nationale Party. How much, or even if, the “Quiet Revolution” directly influenced the club’s decision to move from Lachine to its current location off of the island, I cannot confirm; however, contemporary reports cite tax hikes and encroaching urban expansion as the prime motives for the move.

By 1963, the club was ready to move to Geoffrey Cornish’s new golf courses, leaving Willie Park Jr.’s old ones to the public, under the guise of the Meadowbrook Golf Club. Slowly, as tends to happen, land around the periphery of the property was sold, holes were rerouted or built across former corridors, and maintenance abandoned its care. Even when examining aerials, one must look hard to find lingering traces of what Willie built; yet, at the northwestern end of the property, along the still-active railyard, one clear holdout par 3 remains, albeit with a shifted tee box and a differently sized green beyond two fronting bunkers. Analyzing the hole-by-hole description given to preview the 35 Open, it corresponds closest to that which was provided for the 205 yard par 3, 15th: “A difficult par 3 with traps waiting for under-clubbed shots. There is alot of room on both sides of the wide, sloping target.” Standing on the tee now, eyeing the shot, not even the most romantic of minds is likely to be transported to any of Willie’s other, better preserved golf courses, but it’s there. He was here and built this; of that there is little doubt.

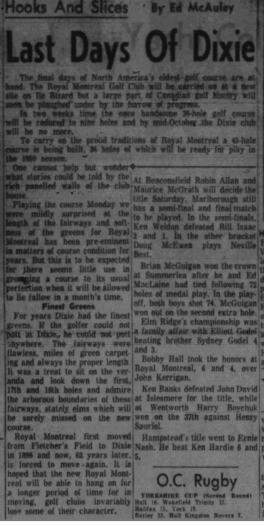

Perhaps a more careful study of the ground, under the overgrown trees or near the fences, might reveal more landforms remaining from Summerlea; however, fifteen minutes away, once you drive by staple upon staple of cookie-cutter suburbia, you’ll find nothing of the other 36 holes that Park Jr. designed in Lachine, Quebec, for the Royal Montreal Golf Club at its Dixie site.

Eulogizing the club’s Dixie era prior to its move northward to Ile Bizard, Ed McCaulay lamented that “The Royal Montreal Golf Club will be carried on at a new site of Ile Bizzard but a large part of Canadian Golf History will be plowed under by the furrow of progress. […] One cannot help but wonder what stories could be told by the rich paneled walls of the clubhouse.”

Despite the disappearance of the sight and sound of golfers nearby, the building, which, along with Willie’s 36 holes of golf, was erected as a token to commemorate the 50th anniversary of North America’s oldest club, housed a local academy until 2020, when, as with Summerlea’s about sixty years prior, a fire reduced it to rubble.

On the cusp of when Willie’s new golf course was about ready to be unveiled next to its elder sister, an original Willie Dunn design onto which Willie added a second significant round of modifications seven years after Harry Colt had first tinkered with it in 1913, The Montreal Gazette stated that “records of the past carry their own interest. When to the message of the written page can be added the testimony of living men the interest increases, and when the record of may be further completed by the imperishable, if changing, memorial of the land, then the whole matter reaches the stage of a fascinating romance. At first glance, it might not, perhaps, be considered probable that the records of a golf club—especially in Canada—could carry any such interest or stir in the reader any emotion beyond the mere curiosity.”

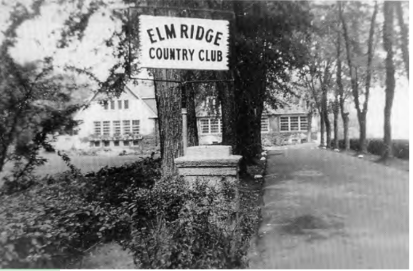

Nostalgia is, after all, a product of dissatisfaction; and that is precisely what “Quebec’s Cult of Destruction”, as I termed it, which is nowhere more evident than here in Lachine, has left us with: nostalgic longings elicited from staring at black and white aerials, or reading clippings in newspapers now a century vintage. It has caused a young man such as myself to drive an hour and a half on a Saturday, pay 40$ to suffer through every sort of degeneracy that the lowest form of public golf can foist upon a person merely to play one mid iron shot (in the pouring rain no less), and spend hours sorting through online clippings and journal sources for crumbs of yesteryear to feed this fascinating romance of golf in its halcyon years in Canada. What we would give to be able to go back in time and play them. Yet, the thought also smolders in our fancies, that if the Lido, a far more a complex construction than either of Park Jr.’s creations, could be brought back to life, then maybe, just maybe, The Royal Montreal, in particular, when that fast approaching time comes, might opt for a similar revival of its Dixie Courses. After all, the plot of land upon which its pair of courses currently sit is not too dissimilar from that which the club occupied in Lachine; moreover, there is plenty of room to rework the routing, if need be. Or perhaps it will be Elm Ridge, with its lost A.W. Tillinghast golf course.

4 000 yards westward from where the burnt Dixie clubhouse has been replaced by yet another glass-fronted, twenty story high condominium building, this latter club’s former clubhouse looms as the best preserved monument to this era of golf. Unlike the meddled with par 3 and the three dilapidated greens at Meadowbrook, however, the structure remains more or less how it was until the associated A.W. Tillinghast golf course around it disappeared in the early 1960s.

Like the other two clubs, taxation, encroachment, and the typical provincial malaise of “blind greed for newness merely for the sake of newness”, as Marie Hélène Voyer defines it in her volume The Habit of the Ruins, were the motivating forces to leave the neighborhood and seek new grounds on Ile Bizard, too, just to the west of the Royal Montreal’s current location. Now, looking around contemporary Lachine, its streets, lawns, driveways, roads, parking lots, and stores, perhaps Sebald’s narrator in Ring of Saturn said it best: “on every new thing there lies already the shadow of annihilation.”