Who Was Hugh Wilson?

by

Mike Cirba

June 2013

“There was peculiar pleasure in revisiting Merion after an interval of years for I have known the course since its birth. Yet, with it all, there was keen regret that my old friend Hugh Wilson had not lived to see such scenes as the National Open unfolded over the fine course that he loved so much. It seemed rather tragic to me, for so few seemed to know that the Merion course was planned and developed by Hugh Wilson, a member of the club who possessed a decided flair for golf architecture. Today the great course at Merion, and it must take place along the greatest in America, bears witness to his fine intelligence and rare vision.” – A.W. Tillinghast – “Golf Illustrated” – July 20, 1934

We all know the legend.

A novice member – a fresh-faced, inexperienced insurance salesman is inexplicably picked by the vaunted Merion Cricket Club to design their new golf course in 1911 and creates a masterpiece.

Towards that end, he makes a trip to the mountaintop to visit with the sage Charles B. Macdonald at National Golf Links, absorbs the imparted wisdom of what constitutes great golf holes, goes overseas to confirm that vision, and then voila’, alchemy ensues!

Seemingly coming out of nowhere to prominence, he devotes his short life to the creation and modification of the Merion East course which he largely perfects before dying just after the 1924 US Amateur.

It makes for a compelling Walter Mitty-ish story, and as with most legends, it is an oversimplified mixture of truth and fiction. Troubling to the student of golf history, however, is that this commonly accepted, reductionist version of Wilson’s architectural achievements minimizes the prodigious effort required to create one of America’s greatest golf courses. Similarly, the related characterization of Wilson as an architectural savant ironically serves to diminish the efforts of man primarily responsible for that creation.

The real story of Hugh Wilson is one of raw talent refined by educated privilege and sharpened by dogged devotion, boundless curiosity, and almost obsessive persistence. Although he remains somewhat of an enigma, what we do know about the real man is much more fascinating than the myth.

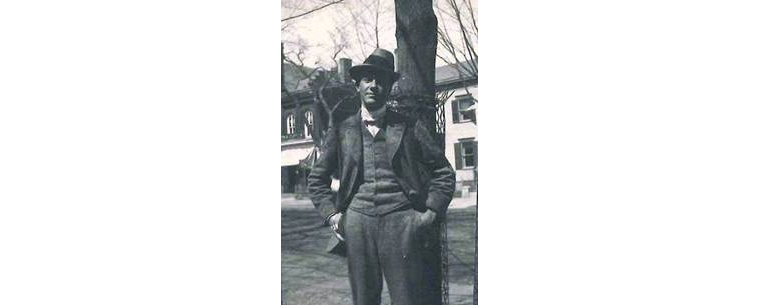

By all accounts humble and unassuming, Wilson exhibited a streak of competitive impatience for getting things done “yesterday” often seen in those who die too young. This insistent ambition was tempered with a reservation for the personal limelight that preferred to let his work speak for itself. Born into upper-crust society in 1879 at Trenton, NJ, not much is known of Wilson’s childhood except that he attended the best private prep schools in Philadelphia and surrounds before enrolling in Princeton University in 1898. While he was highly active in sports, it was golf where the spindly, sometimes sickly Wilson excelled. At the age of 18, he held the competitive course record and was club champion at his home club (Belmont Cricket Club, which later became Aronimink), and became Captain of the Princeton golf team in 1902. It was during his time at Princeton that he likely had his first exposure to golf course design and construction, when a new course designed by Scottish émigré Willie Dunn was being built for Princeton while Wilson served on the club’s Green Committee during his junior and senior years.

After graduation the young Hugh went to work in his family’s insurance brokerage business, and became a full partner by 1905. He met his wife to be, Mary Warren in 1898, and after a lengthy courtship was engaged in 1903 (joining Merion that same year) and married her in October of 1905, with Mrs. Grover Cleveland in attendance. A year later their first daughter Louise was born, followed by another daughter, Nancy, in September of 1910.

Wilson’s early 20s were also the pinnacle of his competitive golfing accomplishments, representing Philadelphia in the prestigious “Inter-City Matches”, held annually between the top amateurs in Philadelphia, Boston, and New York, the predecessor to today’s Lesley Cup. In an interesting wrinkle for architectural aficionados, the 1903 match featured A.W. Tillinghast and Hugh Wilson playing for Philadelphia against a New York team with Charles B. Macdonald and Devereux Emmet. (Walter Travis was also a frequent star of competitions Wilson played in while at university, as well as H. Chandler Egan from Harvard.) Ironically, it was these very matches, and the fact that Philadelphia was often on the losing end that spurred a movement among top golfers in the region who believed the city needed to build challenging golf courses to spawn top championship golfers Wilson, asked a few years later by A.W. Tillinghast what was wrong with Philadelphia golf, replied; “My thought in the matter is that it is due to three causes. First. Lack of encouragement to the younger players. Second. Lack of a public course. Third. Lack of tournaments which will bring good out-of-town players to Philadelphia.”“ Wilson would spend much of his life addressing all three.

Golf in the United States at that time was very much a game of advantaged privilege among the upper class who could afford both the time and expense of participating in the imported pastime. Generally men of higher education and social refinement, they were looked upon, and looked upon each other, as “gentlemen” whose status was partially defined by their athletic participation and prowess. The expectation, somewhat conveniently given their economic status, was that these endeavors would remain untainted by money or profit; the so-called “simon-pure” amateur status.

By contrast, the early Scottish and English émigré golf professionals who came to earn a living and spread their native game were viewed as part of the common laborer class, and restricted from even entering the clubhouse of many of the clubs where they served. In the course of their duties, they were expected to give lessons, make clubs, run the shop, tend to the course, and perhaps most importantly in those early days, utilize their perceived native “expertise” to lay out of new golf courses, most often over the course of only a day or two for modest compensation.

Other clubs bypassed that step entirely, often for economic or egocentric reasons, and had courses laid out by members somewhat familiar with the game, usually some of the better players under the generally mistaken belief that their athletic skill would somehow translate into inspired architectural acumen.

That almost none of these early courses were anything but rudimentary and often crude playgrounds for the elite was simply commensurate with the elementary understanding of the game that existed in the states at that time. However, by the turn of the 20th century, more knowledgeable and prominent American golfers like Charles Blair Macdonald (who had been schooled in St. Andrews) began to publicly bemoan the lack of quality golf courses in the United States, particularly in comparison to what existed abroad. This dissatisfaction eventually led Macdonald on a decade-long quest to first define the best golf holes in the world, and then attempt to replicate their strategies on a single “Ideal” course. This effort culminated in Macdonald’s creation of the first great American golf course at National Golf Links of America (NGLA) in Southampton, L.I., officially opening in 1911. Other early notable exceptions to the rule by 1910 included Myopia Hunt Club, in MA, which was largely developed and refined by amateur sportsman Herbert Leeds over the better part of a decade, and Garden City Golf Club in NY, which was created by amateur Devereux Emmet and then developed into a stern test of golf by amateur champion and club member Walter Travis.

It was against this backdrop that the Merion Cricket Club in 1910 decided to look for a new site for a permanent golf course. Land surrounding Philadelphia was rapidly increasing in value and their golf course was on leased land at risk of being sold out from under them. In addition, the acceptance of the new far-flying “Haskell” rubber-cored ball had made their course a bit short for the sporting tastes of the competitive membership. As member Richard Francis recollected in the 1950 US Open program, “In 1909 or 1910, it became apparent that the old golf course…was antiquated and it was decided to build a new course. The Committee in charge of laying out and building a new course was composed of Mess’rs Horatio G. Lloyd, Rodman E. Griscom, Hugh I. Wilson, and Dr. Harry Toulmin. I was added to it, probably because I could read drawings, make them, run a transit level and tape.”

The land eventually selected by the club was part of a sophisticated deal where the golf course was designed with fronting estate properties along its boundaries, maximizing their value. There was some question as to whether the land itself was suitable for an excellent course, and in that regard, Rodman Griscom hosted his friend Charles Macdonald and his son-in-law H.J. Whigham in June of 1910 with the intent of gaining their learned insight. In a follow-up letter the next month, after stating reservations about both the limited size of the property under consideration as well as the clay-based soil, Macdonald and Whigham somewhat grudgingly recommended the creation of a 6,000 yard course on the site and advised contacting Baltusrol Golf Club regarding the proper treatment of the soil for growing grass and draining water in a clay-based environment. They also advised contacting agronomic experts in Washington, DC for detailed soil analysis.

Although we generally take excellent golf turfgrass conditions for granted today, this was no small consideration for these early pioneers. Macdonald himself had significant problems growing healthy turf at his National Links, even with the seeming advantage of rapidly draining sandy soil near the sea. Indeed, quality of turf was as much a consideration as any architectural or strategic considerations of the course itself, and it was being painfully learned that whatever knowledge of maintaining grasses most foreign born professionals brought with them from their seaside courses was not translating effectively to inland soils and grasses in the states. The organic process to improve that dire agronomic situation to support a rapidly growing game had only just begun.

Merion East 1912

The men of Merion were inspired by what Charles Macdonald and his Committee were accomplishing at NGLA and that they wished to emulate that success. In modern times, when “golf course architect” is an established and respected profession, we may find it odd that Wilson and his Committee of amateurs were selected by their club for the task of creating their new golf course. In truth that was how most of the best courses (like NGLA) were created and developed at the time, primarily due to the amount of ongoing effort and trial-and-error architectural and agronomic revisionism required to evolve a truly superb golf course into being. This contrasted significantly with the brief amount of time clubs were willing to pay service fees to a professional. The best examples of how to do it well had been accomplished by the friends and golfing acquaintances of these men at Myopia, Garden City, and NGLA, so a spirit of amateur competitiveness as well as collaborative scholarship likely played into the decision.

In the case of Merion, the five men selected happened to be five of the six best golfers at the club. In addition, Dr. Toulmin was involved previously with the laying out of the Belmont Club where Hugh Wilson learned the game, and both Griscom and Lloyd were members of the Merion Green Committee for a decade and likely were both involved in the design of the second nine of Merion’s original course which was built on Griscom’s father’s land. Indeed Griscom and his sister had prior studied golf at North Berwick, learning the game under revered professional Benny Sayers. Richard Francis was a surveyor and engineer by trade, skills that would serve the Committee well in their fledging enterprise.

That didn’t mean the Committee knew what they were doing, necessarily. Golf and the creation of golf courses had evolved in the decade or so since these men had their prior experiences and concepts of strategy and “scientific bunkering”, as well as sound agronomic and maintenance practices had advanced well beyond where they had been at the turn of the century.

Hugh Wilson summed it up with characteristic modesty when he wrote later, “The members of the Committee had played golf for many years, but the experience of each in construction and greenkeeping was only that of the average club member. Looking back on the work, I feel certain that we would never have attempted to carry it out, if we had realized one-half the things we did not know.”

Wilson was nothing if not resourceful, however. Like most intelligent men in positions of responsibility recognizing a challenging predicament, Wilson pursued expert advice. In early 1911, shortly after the new land had been acquired, Wilson initiated what was to become a remarkable ongoing and voluminous series of correspondences with Dr. Charles V. Piper and Dr. Russell A. Oakley (the Washington-based agronomists Macdonald had recommended) who were among the earliest scientists to conduct studies in the fields of turfgrass science and golf course management. Their advice and testing of soil and turf samples sent from Wilson proved invaluable and over the next decade the men shared over 2,000 letters on matters of common agronomic interest. These efforts eventually culminated in their collaborative efforts becoming formalized with the creation of the USGA Green Section in 1920, Piper and Oakley serving as co-chairmen.

Similarly, Wilson and his committee sought advice from the acknowledged expert in matters of golf course architecture, Charles Macdonald. Macdonald was the self-proclaimed Father of Golf in this country, and was often consulted by golf clubs for his expertise. A July 1905 “New York Sun” article stated, “He laid out the first course of the Chicago Golf Club…where the distances and the order of holes was the same as at old St. Andrews, and he has been called in as a friendly adviser whenever a noted course has been in construction in the East.”

In early March of 1911, Wilson and his committee ventured to NGLA to visit Macdonald and Whigham. Wilson later wrote, “Our ideals were high and fortunately we did get a good start in the correct principles of laying out the holes, through the kindness of Messrs. C.B. Macdonald and H.J. Whigham. We spent two days with Mr. Macdonald at his bungalow near the National Course and in one night absorbed more ideas on golf course construction than we learned in all the years we had played. Through sketches and explanations of the correct principles of the holes that form the famous courses abroad and had stood the test of time, we learned what was right and what we should try to accomplish with our natural conditions. The next day we spent going over the course and studying the different holes. Every good course that I saw later in England and Scotland confirmed Mr. Macdonald’s teachings. May I suggest to any committee about to build a new course, or to alter their old one, that they spend as much time as possible on courses such as the National and Pine Valley, where they may see the finest type of holes and, while they cannot hope to reproduce them in entirety, they can learn the correct principles and adapt them to their own courses. Our problem was to lay out the course, build and seed eighteen greens and fifteen fairways.”

Evidently, the time spent with Macdonald at NGLA had immediate impact to the group’s ongoing efforts. As recorded in the Merion Cricket Club’s Board minutes from April, 1911, “Your committee desires to report that after laying out many different courses on the new land, they went down to the National Course with Mr. Macdonald and spent the evening looking over his plans and the various data he had gathered abroad in regard to golf courses. The next day was spent on the ground studying the various holes, which were copied after the famous ones abroad. On our return, we re-arranged the course and laid out five different plans.”

Wilson’s brother Alan echoed the value of Macdonald and Whigham’s advice when he wrote in 1926 after his brother’s death, “Those two good and kindly sportsmen, Charles B. MacDonald and H.J. Whigham, the men who conceived the idea of and designed the National Links at Southampton…twice came to Haverford, first to go over the ground and later to consider and advise about our plans. They also had our committee as their guests at the National and their advice and suggestions as to the lay-out of Merion East were of the greatest help and value. Except for this, the entire responsibility for the design and construction of the two courses rests upon the special Construction Committee, composed of R.S. Francis, R.E. Griscom, H.G. Lloyd. Dr. Harry Toulmin, and the late Hugh I. Wilson, Chairman. The land for the East Course was found in 1910 and as a first step, Mr. Wilson was sent abroad to study the more famous links in Scotland and England. On his return the plan gradually evolved and while largely helped by many excellent suggestions and much good advice from the other members of the Committee, they have each told me that he is the person in the main responsible for the architecture both of this and of the West Course.”

As instructors, Macdonald and Whigham seemed equally pleased by the Committee’s final efforts. In early April, Macdonald and Whigham came back to Ardmore for the second and final time to review and advise on the newly developed plans. From the April, 1911 MCC Minutes; “On April 6th Mr. Macdonald and Mr. Whigham came over and spent the day on the ground, and after looking over the various plans, and the ground itself, decided that if we would lay it out according to the plan they approved, which is submitted here-with, that it would result not only in a first class course, but that the last seven holes would be equal to any inland course in the world.”

That plan was subsequently accepted by the Board and construction commenced in the spring of 1911. Others, such as AW Tillinghast shared Macdonald’s optimism when he wrote that spring; “I have seen enough of the plans for the new course as to warrant my entire confidence in the future realization of the hopes of the committee.”

For many years it was believed that Hugh Wilson sailed to Europe to study the great courses prior to the routing of the golf course at Merion. That interpretation is understandable based on the a number of factors, not the least of which was the “Philadelphia Inquirer’s” account the day after the course opened; “Mr. Hugh Wilson went abroad to get ideas for the new course and helped largely in the planning of the holes.”

Over the past decade, however, a series of golf historians and researchers made discoveries that showed that to be in error; Wilson did not travel until early March, 1912, staying for approximately two months while the routed course was growing in. First, a ship’s manifest showing Hugh Wilson coming back from Cherbourg, France in May, 1912 was found by a researcher at an online archival site. This corresponded to a letter to Piper & Oakley from Richard Francis in March, 1912 that mentions Wilson was abroad, as well as later articles found in European newspapers mentioning an American there to study golf courses. Finally, a Philadelphia “Evening Telegraph” article from June 1912, written by golf pioneer and architect Alex Findlay where he interviewed Wilson was found and indeed confirmed that this was Wilson’s first trip abroad.

Findlay wrote; “The writer spent a pleasant hour last Wednesday afternoon with Hugh I. Wilson,

wandering over the new Merion golf course, which he has spent so much of his time on. His main object is to make this the king-pin course of Pennsylvania…Wilson had no end of a good time, and is sorry at not having gone over years ago. It certainly broadens one’s ideas. He now possesses golf knowledge that will stand him in good stead for many years to come…Wilson made a study of the topography of the whole golfing country, such as H.C. Leeds did before he built our greatest American golf course, Myopia, near Boston, and C.B. Macdonald and his National course…We need such men as Wilson to help build up the nation’s ground for the coming game of golf.”

From the accumulated articles, we can glean that during his trip abroad Wilson visited a number of prominent courses in Great Britain and Ireland, including St. Andrews, Muirfield, Prestwick, Deal, Hoylake, Portrush, Formby, Sunningdale, Swinley Forest, North Berwick, Troon, and Princes. It had been rumored for years that Hugh Wilson’s daughter Louise had claimed her father had a return ticket for the maiden voyage of the Titanic, but was providentially detained. Again, that would be consistent with the timing of the trip in the spring of 1912.

Given our modern notions about golf course architecture and construction, where the expected result on opening day is a finished and polished product, it is perhaps surprising that Wilson’s trip abroad had nothing to do with locating and routing eighteen tees and greens on the new land. Instead, the trip’s intent was to foster a process of continuing improvement, experimentation with ideas and best practices, and placing hazards and strategic interest over time as play was observed. A few articles give us some insight into the process. Committee member Richard Francis wrote; “While the Committee was at work, Mr. Wilson went to the British Isles to study golf-course design, and returned with a lot of drawings which we studied carefully, hoping to incorporate their good features on our course. One hole which benefited was the 3rd. It was copied from the Redan at North Berwick. The location of the 3rd lent itself to this design”.

It is illuminating to note that the intent was not specifically to find a place on the new Merion land to build a copy of the Redan hole, but instead the promontory location of the third green lent itself to the Redan bunkering scheme. Indeed, while there are holes at Merion which attempt to copy the strategic principles of great holes abroad like the sixth which is patterned after the Road Hole at St. Andrews, or the original (and later abandoned) tenth hole “Alps”, most of the foreign influences are subtler, such as the “Valley of Sin” fronting the seventeenth green, or the sloping green and bunkering pattern of the fifteenth green designed to resemble the Eden. A.W. Tillinghast, writing in American Golfer in January 1913 under the pen name “Far and Sure” described the borrowing of specific features from abroad, with a caveat; “Mr. Wilson visited many prominent British courses last summer, searching for ideas, some of which have been used….Many of the imported ideas of hazard formation are good…However, I think that the very best holes at Merion are those which are original, without any attempt to closely follow anything but the obvious.”

Wilson had the decided advantage of first seeing Macdonald’s versions of many of the ideal hole concepts and attempted reproductions at NGLA before the routing at Merion was determined, and then benefited from seeing the originals when he went abroad later with specific intent of seeking refinements to incorporate at Merion over time.

Tillinghast described this evolutionary process at Merion for “American Cricketer” magazine in January, 1913; “”Before winter came down on us I visited Merion to play over the new course for the first time. I liked it then, but I permitted weeks to pass before I attempted to put my impressions on paper. It must be remembered that the golf course is unlike a book or the play, for it is not a work that is finished and to be judged as it is. As a matter of fact, a golf course is never completed, and Merion is at present in a very early stage: consequently we must regard it as the foundation from which there will gradually rise the structure of the builder’s plans. To attempt an analysis of some of the holes today would be manifestly unfair, for they are not nearly so far advanced as others, and yet some day the very holes which now are rather uninteresting and featureless may be among the best of them all…As I’ve already said, comparatively few pits have been placed. The committee wisely desires this to be the work of time…Every hazard is more or less experimental, and when the real digging is started, the pits and mounds will be sufficiently terrifying, I am told. Summing up my review, I believe Merion will have a real championship course and Philadelphia has been crying for one for many years. The construction committee, headed by Hugh I. Wilson, has been thorough in its methods and deserves the congratulations of all golfers. ”

Tillinghast, as “Far and Sure” expressed similar sentiments; “It is too early to attempt an analytical criticism of the various holes for many of them are but rough drafts of the problems, conceived by the construction committee, headed by Mr. Hugh I. Wilson. Mr. Wilson visited many prominent British courses last summer, searching for ideas, some of which have been used.” Alex Findlay wrote much the same in his course review, “There are a few nice water hazards, and also a few sand ones, but the placing of the mental hazards, etc., will be left until spring. One can by that time find places wherein shots will lie, and place hazards accordingly.”

With the new course opened for play, the membership wrote the club president proposing a dinner and gift to honor Hugh Wilson’s contributions. It read, in part; “A number of the golfers of the Merion Cricket Club, who appreciate the great amount of work that has been put upon the present course by the Construction Committee, consisting of Messrs. Lloyd, Wilson, Griscom, Francis, and Toulmin, propose to give this Committee a dinner and on this occasion present Mr. H.I. Wilson with a suitable gift for his painstaking, diligent, and efficient work in the construction of this beautiful course. Mr. Wilson has spent many hours of careful study, and has devoted every moment of his spare time in laying out and constructing this course. He has been ably assisted by the members of the Committee, but there is no one who has devoted the time and energy and real hard work on it that he has.”

The new Merion course that opened in September 1912 would likely be unrecognizable in stretches from the course we know today. Even by the summer of 1915, nearly three years after opening, the golf course was described as having “less traps and bunkers than are usually to be found on a short nine-hole course”. The first hole aimed the golfer directly and uncomfortably close to the boundary of Golf House Road. Four holes originally crossed Ardmore Avenue and a number of original greens were less than desirable in terms of configuration for approach shots. Committee member Richard Francis with good humor mentioned some of these issues in his 1950 remembrances; “In those days we thought Ardmore Avenue would make a fine hazard. Play crossed it on the 2nd, 10th, 11th, and 12th holes. The trouble was, Ardmore Avenue soon got over being a country road through farmland and became a much travelled highway. The 2nd tee, which was just back of the 1st green, was rebuilt almost immediately on the other side of the highway – where it now is – but the other 3 holes remained unchanged until some time in the 1920’s. More land was obtained at that time and the 10th, 11th, and 12th holes, were redesigned and a new 1st and 13th constructed…The 14th green was rebuilt…Somewhere along the line the 2nd green, a three-terraced affair, referred to as “awfully interesting”, was rebuilt as it is now. Originally the 8th green took the contour of the hillside so that players had to play onto a green which sloped sharply away from them.”

While the course did have its limitations, the combination of potential challenge, natural interest, and fine conditioning led most observers to agree with Tillinghast’s assessment, including Alex Findlay who concluded; “The construction committee, consisting of Hugh I. Wilson, H.G. Lloyd, R.E. Griscom, R.S. Francis, and H. Toulmin have done for Pennsylvania what Herbert C. Leeds and his committee did for Massachusetts – built the two nicest courses in their respective states.”

Merion West 1913

The proverbial paint had barely dried on the just opened East course and Hugh Wilson and his committee were called back into service by Golf Committee Chairman Robert Lesley in December of 1912. Only three months after opening, membership rolls burgeoned such that a fixed limit had to be placed on golfing members. Tillinghast reported; “Merion has increased its membership to the bursting point, and it has been found necessary to place a limit. The course has been practically congested over since it opened. The golfers wanted to play over a real course, and they flocked there. Additional ground has been secured, and another eighteen hole course will spring up beside the other.”

Working on a lovely rolling site just a mile west of the East course, Wilson and his Committee took what they learned in the previous months and fast-tracked the creation of the club’s second course, Merion West. Although the official opening date was in May of 1914, by November of 1913 Tillinghast was able to report in “American Golfer”; “Merion has opened the second new course for play. Your correspondent went out to look over the newest lay-out, for the purpose of describing it in THE AMERICAN GOLFER but before he had gone very far with Mr. Hugh Wilson, Mr. Rodman C. Griscom and Mr. H.W. Perrin, the heavens opened and the floods descended, the party being forced to take refuge. However, through the deluge I saw something of it…It is undeniably sporty and golf is spectacular to an extreme. Mr. Hugh Wilson and the construction committee have worked exceedingly hard and the various problems appear to be worked out in masterly fashion.”

Robert Lesley was understandably proud of the new 36-hole complex, and compared the two courses in an article for “Golf Illustrated” in December of 1914; “The first fact that strikes one in considering the two courses at Merion is their absolute difference in soil and in surrounding country scenery. The old or east course is…in general characteristics a flat area, intersected with two or three creeks, and having about it in the shape of homes and other improvements, many of the indications of an advanced civilization. The soil is largely clay loam, the holes are long, the going is good, the run of the ball is great and there is a freedom and openness about the course that tempts the man to lash out with a driver or brassie and to let go at almost every hole…requiring the best of club workmanship. The new course…presents an entirely different picture. Where on the old course backgrounds seem to be lacking in many of the holes, a forest, which surrounds the new course, furnished a background to almost every hole. Where civilization seems to mark the old course, forests, hills and dales mark the new one. Both courses are of championship size, the old of 6,420 yards and the other of about 6,015. The new, although shorter, furnishes equally good golf.”

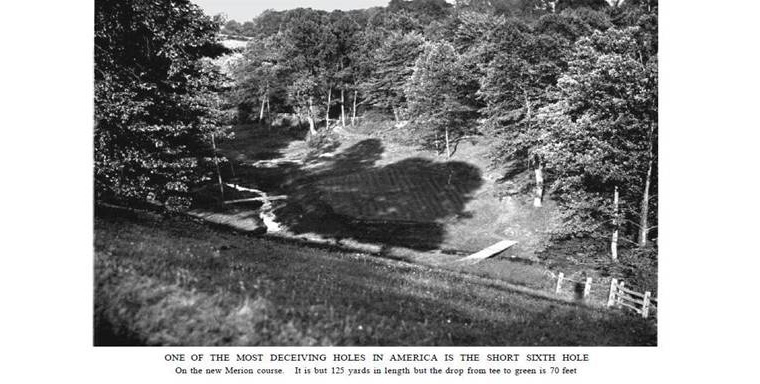

Indeed, when the US Amateur tournament was played at Merion just two years later in the fall of 1916, both courses were used for the Medal competition. While it had its detractors (both Tillinghast and Walter Travis felt it had too many short and quirky holes for a major competition like the 125 yard steeply downhill 6th over a creek or the equally steeply uphill short par four 8th), the great English architect Charles Alison commented, “Of course, I know the East is your championship course; yet while it may be heresy for me to say so, I like this one even better because it is so beautiful, so natural and has such great possibilities. I think it could be made the better of the two.”

Over time, significant additional enhancements to the East course have kept it relevant for high-level competitions, while the West course has remained relatively untouched, time and technology having relegated it to a still honorable status as a fun, sporty, remarkably lovely “member’s course”.

In 1934, writing for the US Open preview, long-time club President Robert W. Lesley again summed up the origins of the two Merion courses thusly; “…when Merion’s first golf course was found to be too short for satisfactory championship play with the development of the rubber cored golf ball, it was necessary to do something of a radical nature. A new location was sought and in 1912 127 acres were purchased…Hugh I. Wilson and his Green Committee laid out Merion’s first 18 hole course on the new land and it is what is today now known as the “East Course.” This development soon added so many members to Merion’s golf players that some immediate action became necessary to add further to the facilities for golf…and a second eighteen-hole course, now known as the “West Course”, one o the most beautiful in the country from a scenic standpoint, was created by Hugh I. Wilson and his associates on the Green Committee….those two courses, both of which are of championship character and have received the most favorable comments in golf circles all over the world, it may be stated that the reason for the successful development is due to the fact that during the period from 1909 to the present day Merion’s Green Committee has been kept almost intact from its origin up to today…thus insuring a consistent, systematic, and wise development.”

Philadelphia Public Course Committee 1913

For the game to grow in Philadelphia and to help develop competitive players, most of the influential golfers in the region felt it was essential that the game be made available to the “men of slender purses”, as Tillinghast put it, in the form of a free public golf course on city lands. Robert W. Lesley of Merion was serving as President of the Golf Association of Philadelphia (GAP) in 1913, and became the primary catalyst. For over ten frustrating years, the Golf Association had tried to work with the city officials of Philadelphia to create a public golf course in the city’s park system, to no avail. In January of 1913, however, Lesley appointed a committee comprised of the Presidents of six influential clubs, all men of distinguished community presence who were felt to hold sway over public opinion and well versed in political maneuvering. Two of those men were Clarence Geist of Whitemarsh Valley, a wildly wealthy Chicago import who owned the Atlantic City Gas Company and Ellis Gimbel of the city’s prominent Jewish club Philmont, whose family had created the Gimbel’s Department Stores.

In February of 1913, Lesley created a second committee whose responsibility was to scour the city’s sprawling Fairmount Park System and find a suitable location for a public golf course. This was a challenge because the golf couldn’t interfere with other public activities, and the Fairmount Park Commission had a decree that no trees could be taken down for any purpose, including golf.

The Committee consisted of “Hugh I. Wilson, Merion Cricket Club; George A. Crump, Philadelphia Country Club (and creator of Pine Valley), A.H. Smith, Huntingdon Valley Country Club; and Joseph A. Slattery, Whitemarsh Valley Country Club…”, and in late April of 1913 they issued their initial report, recommending a site near Belmont Mansion. It was reported, “…Hugh I. Wilson of the Merion Cricket Club, who was one of the two expert golfers present, declared that he believed Plot C would be the first one turned into a golf course. He stated that it was admirable soil, which would only need a little fertilizer to be put into condition.”

In June of that year, the Belmont site was rejected by the Fairmount Park Commission. By then, however, the Committee had located another site in the far northwest corner of the city which they described as ideal for golfing purposes. The Committee’s subsequent proposal was approved and it was recommended that council appropriate monies for a public course in the newly acquired Cobb’s Creek Park.

Seaview 1913-14

It is not known if it was the Public course committee that first drew wealthy Clarence Geist and Hugh Wilson together, but by the spring of 1913 Geist was developing plans to create a palatial resort on some low-lying farmland along the bay in Absecon, NJ, just outside of Atlantic City. Certainly as an “amateur architect”, whose real source of income was the family insurance business, it is difficult to imagine that Hugh Wilson would have been soliciting additional golf-related work. Still, after the success of the Merion East course (the West was still only being constructed at that time), it seems Wilson’s star was on the rise in Philadelphia sporting circles, and he quickly became the go-to guy for a number of golf-related projects.

Clarence Geist was unhappy with the crowding and slow-play at the public Atlantic City Country Club where he played each winter and felt the moderate temperatures near the sea would afford him the opportunity to turn Seaview into a year-round private club and resort.

An earlier day Donald Trump-like tycoon with a similar enormous ego, much of what was released to the press about the project bore the Geist stamp. Never one to put others in the forefront, the details of the men behind the project were not heavily publicized, and given Wilson’s unassuming nature, he was probably fine with the lack of notoriety. However, in October of 1913, golf writer William H. Evans of the “Philadelphia Public Ledger” noted, “Hugh I. Wilson, chairman of the Green Committee at the Merion Cricket Club and who is responsible for the wonderful links on the Main Line, has been Mr. Geist’s right hand man and has laid out the Sea View course. Mr. Wilson some years ago before the new course was constructed visited the most prominent courses here and in Great Britain and has no superior as a golf architect.”

Despite construction setbacks when a number of holes along the bay became flooded during a January 1914 hurricane, as well as a subsequent revision in plans requiring four new holes to be created further inland, by the summer of 1914 the course at Seaview was ready to open. In June of 1914 The “Philadelphia Inquirer” reported, “The eighteen hole course is in perfect shape. It is prettily laid out for enthusiasts, too, Robinson (course pro Willie Robinson) and Hugh Wilson of Philadelphia, being highly complimented on their choice for the greens.”

In October of 1914, the “Philadelphia Inquirer” reported, “The Seaview, as one of the three most important golf projects undertaken in America, occupies a niche quite its own. It was not intended to be like the National Links, the most severe test ever offered in this country, nor was it designed to cater almost entirely to the closest students of the sport, like Pine Valley. Seaview occupies a middle ground, being planned for thinking players of both sexes with plenty of hazards, which call for the placing of exact shots without undue penalization. It is doubtful if a course has yet been built on this side with such a variety of surface on the putting greens. Those who received a jolt when hammocks were introduced on several greens at Garden City would be speechless over the variety of boundary humps that render every one of the Absecon greens distinctive…Of course, all of the distances on the club card are provisional until experience has demonstrated the wisdom of hazard location.”

Much like both courses at Merion, Seaview was built with limited bunkering with the idea that hazards were best located after careful observation and study of play. Tillinghast wrote in January 1915, “Seaview will never be the test of golf that Pine Valley is. It was never contemplated as such. The course is flat with just enough of an undulation in the fairway to rob the flatness of the ground. Some of the best courses in Great Britain are flat, but thanks to what is known as the Mid Surrey or Alpinization scheme of bunkering, the courses are really of a championship caliber. And that is what Seaview will be in another year. The bunkering has not yet been started and those who saw the course for the first time will be surprised when they see it a year from now…The greens, however, were a delight to all and in spite of their newness they will compare favorably with any course in the country…Each and every green is characteristic and no one resembles the other. All are undulating and all are perfectly true.”

Golfwriter Verdant Greene, perhaps gently poking the movement that religiously copied holes from abroad wrote, “There has been no straining for effect at the Seaview course. No famous hazards abroad or at home have been counterfeited there, nor have distances been stretched nor plans laid to keep contestants from drawing a long breath throughout the round…There are plenty of hazards which call for exact shots, but no ultra-penalization. While the links, as is almost inevitable, being so near the sea, has not great variety of surface, being used as a farm up to two years ago, the putting greens present more undulations and humps than a camel’s back. Even Garden City has been surpassed in that respect.”

Shortly after that “soft” summer opening, Clarence Geist fell deathly ill, and it wasn’t until he fully recovered that the course was officially opened with a prestigious, audacious four-ball tournament with top amateur golfers in the middle of January. By that time, Hugh Wilson was looking to get back to the business of his real business, insurance. He did find time in April of 1915, however, to return to Seaview to play as Francis Ouimet’s partner in defeating Clarence Geist and new Seaview professional Wilfred Reid in a highly publicized match, with Ouimet setting a new club record of 73.

The Seaview course that had its soft opening in summer of 1914 is the same routing that is today known as the Seaview “Bay Course”. An opening day hole-by-hole description reads much like today’s course, and even though Donald Ross was engaged by Geist later in 1915 to “stiffen” the course with extensive bunkering, only some of Ross’s recommendations were ever followed.

Cobb’s Creek 1914

By April of 1914, Philadelphia City Council had appropriated $10,000 of the requested $30,000 towards the creation of a public golf course in Cobb’s Creek Park. GAP President Robert Lesley named a committee to design and help construct the course, working with city engineers. Lesley’s committee was literally a “Murderer’s Row” lineup of men experienced in golf course design and construction from the city’s clubs. It included Hugh Wilson, George Crump and Father Simon Carr, who had begun the work of building Pine Valley, AH (Ab) Smith, two time Philadelphia Amateur champion who had made significant revisions to Huntingdon Valley, George Klauder, who had designed and constructed the new Aronimink course with A.W. Tillinghast and Cecil Calvert, and Franklin Meehan, who had created North Hills country club on his family estate and helped Tillinghast construct his initial course at Shawnee in 1910.

By June, the initial design had been completed, with the Philadelphia Inquirer reporting that, “Experts who have seen the layout say the first course will be the best planned municipal links in this country and that it will compare favorably with some of the best courses in this country.” Not surprisingly, Hugh Wilson was later given specific credit as the man “who drew the tentative design for the course”.

Years later, an account in the “Philadelphia Inquirer” recapped, “Eventually the Cobb’s Creek course became possible, and George A. Crump, Hugh Wilson, Ab Smith, and George Klauder offered to lay it out for the love of the game.”

Philmont 1914

Much like his connection with Geist at Seaview, it seems that Wilson’s participation on the Cobb’s Creek committee with Ellis Gimbel may have been responsible for his being asked to come to Philmont to make recommendations for improving their golf course which had opened in 1908. In November of 1914 the Philadelphia Inquirer reported, “Philmont is also making a lot of changes that will greatly increase the pleasure of playing over that course. The two new holes (both designed by Wilson), the tenth and eleventh, are two of the best short holes in Philadelphia. The greens are well guarded and unless the shots are well placed there is trouble aplenty for the players. The series of up and down hill holes in front of the cub have been improved by the elimination of two of them. Five years ago there were scarcely fifty men who played over the course…Now the golfers are in ascendancy and number hundreds.” In July of 1915 the Inquirer reported, “Philmont is a beautiful course to play on and is a much better test of golf than it was two or three years ago, when the same event was held there….the first four or five holes are particularly good golf as are the new holes, which were laid out by Hugh Wilson, who constructed the two courses at Merion and the one at Seaview.”

In writing retrospectively about Philmont in January 1916, the Inquirer noted, “The last named club (Philmont) for years was noted as a course where there was not a single artificial hazard… One of the leading members (Gimbel) had a great deal to do with the municipal course in Cobb’s Creek Park, which was laid out by A.H. Smith, George Crump, Hugh Wilson, and others, and he was greatly impressed with what these experts did.”

A May 1916 “Philadelphia Inquirer” article details some of the work done by Wilson at Philmont, in conjunction with Green Committee chairman Henry Strouse; “For those who have not played at Philmont it might be said that the course is one of the most interesting in Philadelphia. While there is still a lot to be done in the bunkering of the course what has been done has been done intelligently. Several of the holes, notably the eighth, tenth, eleventh, and thirteenth will compare most favorably with the best holes in and about the city. The eight is patterned after one of the holes at Pine Valley.”

During this same time period, local lore has it that Wilson also designed the nine-hole Phoenixville Golf Club near Valley Forge, although documentation establishing that as fact has still not been uncovered.

North Hills 1914-1917

Much like Seaview and Philmont, it seems the connections Wilson cemented at Cobb’s Creek led to an increasing amount of golf course related work, this time at North Hills Country Club. Franklin Meehan started this venerable club on family property in 1908, and in 1914 once additional land was acquired, a new eighteen hole course was designed by Hugh Wilson, Alan Corson (Assistant Engineer of Fairmount Park and Chairman of the North Hills Green Committee), Meehan, and Ab Smith, all four men at the time involved as well with the Cobb’s Creek initiative. Course construction commenced that year under the leadership of Corson, but it was evidently slow-going.

In January of 1915, Tillinghast wrote; “North Hills has great possibilities, for the natural features are many. In a number of places the ancient mine workings offer exceptional opportunities to the course builder, but unfortunately the club has not been in a position to finance the work which would give them a remarkable course. Lay out North Hills on a big scale and it will be a great golf course.”

The new course opened in 1917, and it’s likely that both Wilson and Merion Greenkeeper William Flynn helped over the next period of years as design drawings coinciding with some revisions and enhancements of the course were found in the “Flynn Collection” drawing years later.

Resignation

By the end of 1914, having designed and built both courses at Merion and Seaview, coupled with additional work at Cobb’s Creek, North Hills, and Philmont, Hugh Wilson needed a break. The December 6, 1914 issue of the Philadelphia Inquirer reported, “Hugh I. Wilson, for a number of years chairman of the Green Committee at Merion Cricket Club has resigned. He personally constructed the two courses at Merion and before the first was built he visited every big course in Great Britain and this country. He also laid out the new course at Seaview. Pressure of business compels him to give up the chairmanship.”

Cobb’s Creek 1915-16

Events soon conspired against Wilson’s wishes to settle back into a business routine. In early January 1915 it was announced that the city had come to agreement to fund and build the golf course Wilson and the others had previously designed in Cobb’s Creek Park.

Shortly after the course opened to sterling reviews, many citing it as the best public course in the country, a “Philadelphia Inquirer” article from July 16, 1916 fleshed out a bit more of the specific involvement of Hugh Wilson and Ab Smith, who seemed to have the most lengthy involvement during the construction phase; “The fact that there is a golf course at Cobb’s Creek is due entirely to the hard efforts of the Philadelphia Golf Association…And after the plans were decided upon Hugh Wilson, the man who laid out the two Merion courses, spent six months laying out the new public course. A.H. Smith, for years one of the most prominent members of the Huntingdon Valley Country Club, gave up his Sundays for as many months to the work of getting the course in shape.”

“The Golf Association of Philadelphia, the Executive Committee, and Messrs. Wilson and Smith have given their services gladly and freely in an effort to make the new course the finest public course in the United States. At no time have they attempted to interfere in the slightest with the Park Commissioners in the running of the links. They have always been ready to give whatever aid they can.”

An April 1916, “Philadelphia Evening Ledger” article discussed the architecture at Cobb’s Creek; “Everything is the latest word in golf architecture. There are no straight lines, none of the greens are built as they were in the olden days of a half decade ago, when the greens were flat as a pancake and rectangular in shape. Everything is irregular in shape, every green is undulating in character and every green faces the shot instead of falling away from it. There are no cross bunkers and there will be none. There are pits and traps, and grassy mounds and grassy hollows.”

As was the standard practice, the job of adding extensive bunkering was deferred; one article saying it was a job “likely to take two or three seasons”. However, the reality is that the course was already more than difficult enough for fledgling Philadelphia public golfers. Another city paper wrote; “Most of the trapping and pitting will go over till next year, as those in charge do not think it advisable to make the course too stiff a proposition in its early stages. The rolling country which makes up the course and the fact that the creek guards quite a number of greens are sufficient at present to make the course difficult.”

As with most of Wilson’s projects, Cobb’s Creek benefited greatly from the involvement of Merion’s Superintendent William S. Flynn, who handled construction shaping and was a budding architect himself at that time. As reported in the Evening Ledger piece, “William S. Flynn, the green keeper at Merion, has been a big aid in the development of the course and in the construction and seeding of the greens and in the actual building of the bunkers and traps. And the work…certainly speaks for itself.”

Flynn had come to Philadelphia while Merion East was being built, likely at the behest of his brother-in-law Fred Pickering who was a man with vast golf course construction experience working with early pioneers Tom Bendelow and Alex Findlay. Pickering was hired by Merion to lead the construction of Merion East and Flynn came to work for him through the course opening. Later, when the West Course was under construction, Pickering and Merion had a falling out over concerns with Pickering’s drinking, and Flynn took over full construction and maintenance responsibilities, eventually leading to the full-time Superintendent job. Pickering did go to work for Wilson again at Seaview, but problems continued and he was eventually replaced.

By all accounts, Wilson and Flynn developed a professionally symbiotic and personally close relationship and worked intimately over the next decade on multiple projects. When Flynn’s first daughter was born, Wilson bought the family an Airedale puppy and later bought Flynn’s wife Lillian a horse and carriage so she could come and visit her husband on the Merion job site.

Flynn so embraced his new responsibilities during this period that he made a trip to New England to study the best courses there, The Country Club, Myopia Hunt, and Essex among them, looking for ideas he could bring back to the Cobb’s Creek construction process. Flynn later became one of the most famous golf course architects in the country during the Golden Age of design, and his elegant style that sought to seamlessly blend the natural with the man-made helped to define what became known as the “Philadelphia School” of golf course architecture. He also is the man responsible for the distinctive “wicker basket” flagsticks that are used at Merion (and were used at Cobb’s Creek), patenting them in 1915.

William Flynn, to whom “naturalness” was the most important design factor, summed up the philosophical approach of the Philadelphia School best when he wrote, “Naturalness should apply on all construction on golf courses, greens, tees, mounds, and bunkers alike. It is much more expensive to construct a natural looking golf course on account of the tremendous amount of material that must be moved but the money saved in the subsequent maintenance greatly offsets the original cost. Natural topographical features should always be developed in presenting problems in the play. As a matter of fact, such features are much more to be desired than made tests for they are generally more attractive.”

Cobb’s Creek set a new standard for public golf when it opened due to the intensive collaborative efforts of men like Wilson, Crump, Smith, Flynn and the others, and unlike many courses of that era, its basic, attractive features have remained relatively unchanged over time.

Merion East 1915-16

In July of 1915, as construction efforts at Cobb’s Creek were nearing completion and the grow-in process begun, the following article appeared in the “Evening Ledger”; “Merion is not trapped and bunkered at present because of the 90 per cent of the club’s golfers who are not cracks. It is sufficiently hard for the remaining 10 per cent and not too difficult to take away a portion of the enjoyment from the others. Should the national championship be awarded to Merion, traps and bunkers could be placed in short order.”

Within months, it was confirmed that Merion would host the prestigious US Amateur championship, which in those days was the most important tournament in the country. Naturally, Hugh Wilson was pressed back into service, this time to add teeth to the club’s course through the creation of stringent bunkering strategies and an attempt to improve some of the course’s basic weaknesses.

Previewing the tournament for “American Golfer” in February 1916, Tillinghast wrote; “Certainly a reference to the Merion course over which the championship of 1916 will be played must be of interest. The course was opened in 1912, and the plans were decided upon only after a critical review of the great courses of Great Britain and America. It was the first of the two eighteen hole courses at Merion, the West Course being opened several years later. The distances are admirable and altogether Merion presents a good test of golf, but in view of the fact that the National title is to be decided there next September, a number of hazards will be introduced to bring the play closer to championship demands.”

With the limited time available to get the course ready before September, Wilson and Flynn must have tore across the landscape of Merion East like a storm bent on construction. Adding over fifty strategically-placed bunkers, all new tees, they also ripped up and rebuilt greens on what are today’s holes 6 and 9, created brand new greens on the 8th and 17th and planted new fairways on holes 10, 11, and 12. Remarkably, the course was in superb condition by the time of the event.

By April 23, 1916 the “Philadelphia Inquirer” reported; “Nearly every hole on the course has been stiffened so that in another month or two it will resemble a really excellent championship course. Hugh Wilson is the course architect and Winthrop Sargent is the chairman of the Green Committee. These two men have given a lot of time and attention to the changes and improvements. Before anything was done to the course originally Mr. Wilson visited every golf course of any note not only in Great Britain, but in this country as well, with the result that Merion‘s east course is the last word in course architecture. It has been improved each year

until it is now nearly perfect from a golf standpoint. The club has been very fortunate in having as its greenkeeper William S. Flynn. He is a New Englander and before coming to Merion was a professional in Vermont.”

On the same day William Evans concurred in the “Evening Ledger”; “These changes have been made by the Green Committee under the most efficient chairmanship of Winthrop Sargent and Hugh Wilson, to whose genius Merion owes both its courses. In addition, Mr. Wilson, for many years chairman of the Green Committee at Merion, also constructed the Seaview course and so altered the Philmont course by adding two new holes that it now ranks among the best courses in Philadelphia. Merion is particularly fortunate in having as its groundkeeper William S. Flynn, under whose personal direction all this work is being done. In intelligence he is heads above the average greenkeeper and in addition is an excellent executive.”

The tournament itself was splendidly received, with Chick Evans defeating Robert Gardner in the finals, and which featured a 14-year old named Bobby Jones who created a stir with a 74 on the West course before fading with an 89 on the East and then losing in match-play. In a statement sure to please Wilson and Flynn, runner-up Gardner later wrote that, “Somehow it did seem to contenders last week that Hugh Wilson…had set the Merion hazards on rollers and shifted them around several times a day as stage hands would scenery.”

Walter Travis was equally laudatory, writing in “American Golfer”, “Great credit attaches to the Merion Club for the superb condition into which they rounded the course generally, despite the handicap of drought. Mr. Hugh I. Wilson deserves great praise for his work in this direction…”

Sadly, just a few months before what should have been the pinnacle of Hugh Wilson’s architectural and agronomic achievements, his youngest daughter Nancy passed away just a month and a half before what would have been her sixth birthday in early September. One can only imagine what a bittersweet event the 1916 US Amateur must have been for Wilson, the semi-final rounds on Saturday the 8th falling on what would have been her birthday.

World War I

While President Woodrow Wilson vainly tried to keep the United States out of conflict, much of the rest of the world had already been at war for years by the end of 1916. Finally, the sinking of American ships by German U-boats created an intolerable situation and America declared war in April of 1917. As one might imagine, golf related activities took an immediate backseat to more critical matters.

During the previous years of rapid golf courses development, there was another reason for keeping amateur architectural work low-profile. Various movements were afoot to make anyone profiting from the game a “professional”, and Francis Ouimet was unfairly stripped of his amateur status for having worked in a sporting goods store. Golf course architects were among those targeted. A January 1917 article in the “Philadelphia Inquirer” mentioned a number of local amateurs; “Only one Philadelphian (Tillinghast) is affected by the rule as all other amateurs have been doing this work as a matter of interest and love of the game. George Klauder had much to do with the laying out of the Aronimink and Cobb’s Creek courses, George Crump had done wonders at Pine Valley, Hugh Wilson built both the Merion courses and the course at Seaview, Ab Smith has done a lot of construction work at Huntingdon Valley, Cobb’s Creek, and North Hills, but it is very doubtful if anyone of these ever got a penny for their services. According to the old rule golf architects were as good amateurs as the veriest dub, who played once a week and were exempted from the ban placed upon those who infringed the amateur rule.”

Pine Valley

Hugh Wilson had great admiration for what his friend George Crump was trying to accomplish at Pine Valley. Likewise, he felt that Pine Valley was an inspirational model for anyone trying to advance their knowledge of golf course architecture. In a news article published in April of 1917, it was stated, “George Crump has been called the “Miracle Man of Pine Valley” and even such an authority as Hugh Wilson, who laid out the two Merion courses over which the national amateur championship was played last fall, advises every club which intends either to build or reconstruct a course to go to Pine Valley to get the ideas about the holes and the bunkering.”

Tragically, on January 24th, 1918, with the war dragging on and George Crump having exhausted a fortune on his Pine Valley dream, Crump committed suicide at age 46. The outpouring of genuine emotion and regret in the world golf community was palpable and profound, and Hugh Wilson shared in that shock and collective grief. With only 14 holes finished, the very future of the great Pine Valley course seemed very uncertain.

By the end of 1918, with the end of war within sight, Pine Valley members asked Hugh Wilson and his brother Alan to come up with a plan to finish the remaining four holes according to George Crump’s expressed wishes. With some generous donations, funding was garnered and the Wilsons spent five months at Pine Valley, working with Crump’s close friends Dr. Simon Carr and William Smith who detailed Crump’s “Remembrances”. The Wilson’s brought in William Flynn to assist in the spring of 1919. Overcoming a number of agronomic challenges, the team was finally able to get holes 12 through 15 completed, which opened for play in the summer of 1920. Work continued on completing Pine Valley through 1922 with the help of Charles Alison when it is generally agreed the course was finalized.

In January of 1920, Hugh Wilson was elected to the Executive Committee of the United States Golf Association, a position of prominence and earned respect for a man who had become somewhat of an accidental leader in the game. Circumstances had simply dictated that he was the right person for the job at reoccurring instances, which ultimately set Wilson on a trajectory that seems almost predetermined, in retrospect.

Merion 1922

By early 1922, as the economy began to prosper in the post-war years and the country zoomed into the “Roaring 20’s”, the increase in auto traffic along Ardmore Avenue created an untenable situation that needed resolution. With this in mind, Merion was able to acquire land south of their original course.

In a February 18th, 1923 article by J.E. Ford (pen name “Donnie MacTee”), the significant changes to the Merion course affecting holes 10, 11, 12, and 13, all effectively replaced, were detailed. More surprisingly, it was learned that this was land that Wilson and the others of his committee had hoped to use originally, but were prevented from acquiring at the time.

“To the legions of golfers who have played the east course of the Merion Cricket Club the statement that these links have been improved will seem incredible. Improving upon perfection, they will say, cannot easily be done. True, perhaps, yet the changes that have been made upon four holes of this championship course since last summer have added greatly to its attractiveness.”

“The new holes are the realization of hopes held by the builders of the course in the days when golf in this country was virtually unknown. At that time it was found impossible to obtain the ground necessary for the construction of ideal holes at the turn. After a lapse of two decades the club has gained title to the necessary land and the new holes, as near ideal as most ever will be, await only spring to prove their worth….”

“Responsible for these improvements in the already unsurpassed east course is Hugh Wilson, a pioneer golfer here and chairman of the Merion green committee for seven years – or until his voluntary retirement. Mr. Wilson was one of the original designers of the Merion course and the holes just constructed are ones he wished for, but was prevented from building when the course was designed. He is still an active member of the greens committee, to whom all questions of architecture and grasses are referred as a matter of course.”

In early 1924, in preview of the US Amateur that was to be hosted by the club that fall, golf writer Frank McCracken discussed the changes and the man responsible; “Merion has been improved upon. The improvements have brought out more of the course’s beauty. That is not all. It will be a test to try the mettle and might of our greatest golfers. Hugh I. Wilson, one of the best known turfologists in these United States and an authority on golf architecture in proportion, is the man mainly responsible. He is chairman of the Greens Committee at Merion. Hugh Wilson does not court attention for his knowledge. He prefers to do things and allows his accomplishments to go unsung. Yet he is considerate. He has the interest of golf at heart, especially the Merion course and the national amateur championship. Trying to keep himself in the background, he has explained what has been done at Merion. In making ready the bunkered battleground for the next national amateur grapple, the first thing considered was the elimination of three shots over a much-used highway. This has been done. Four entirely new holes have been constructed. They are all beauties.”

Despite lingering health issues, by 1922 Wilson again seemed poised to continue his architectural and civic achievements. The city of Philadelphia was in dire need of more public courses, his adored Cobb’s Creek was overflowing with golfers who lined up in the wee hours of the morning, so once again he and Ab Smith (with Alan Corson) were tasked with locating new sites within the city for additional public links. The sites they recommended in the Tacony and League Island sections are today public courses known as Juniata and Franklin Roosevelt, respectively.

Additionally, he may have been part of the design team for the Juniata course before his untimely death In August, 1924, when work began in earnest to build an additional public course at Juniata (Tacony) the following news item appeared in the Philadelphia Evening Ledger;

“The city will be saved a big fee for a golf architect, in the program for the erection of a course in Tacony, Mr. Corson said. He announced that he himself, a golfer, and Frank Meehan, Hugh Wilson and A. H. Smith, all members of the Philadelphia Golf Association, would probably design the course. Mr. Meehan, Mr. Wilson and Mr. Smith gave their aid in laying out the course at Cobbs Creek,” stated the chief engineer, “and I am sure that they will help us with the Tacony links.”

In early 1922 Wilson spent two days with William Flynn and Frederick Hood reviewing the site for Kittansett Golf Club, in Marion, MA. The extent of his total involvement in that design is unknown, but in March he wrote Oakley, “I have just gotten back from Marion, where I spent two days with Mr. Hood and Flynn. It certainly is a pretty piece of ground and it ought to make a bully Golf Course.”

He was also named in 1922 as the pending architect for a new club to be formed in Bryn Mawr, PA, which never came to fruition, and began work over the next year with William Flynn on a new privately-owned (by William Flynn and stockholders including Wilson) public course in the Philadelphia suburbs called Marble Hall. The course opened in the summer of 1925, after Wilson’s passing.

Merion 1924

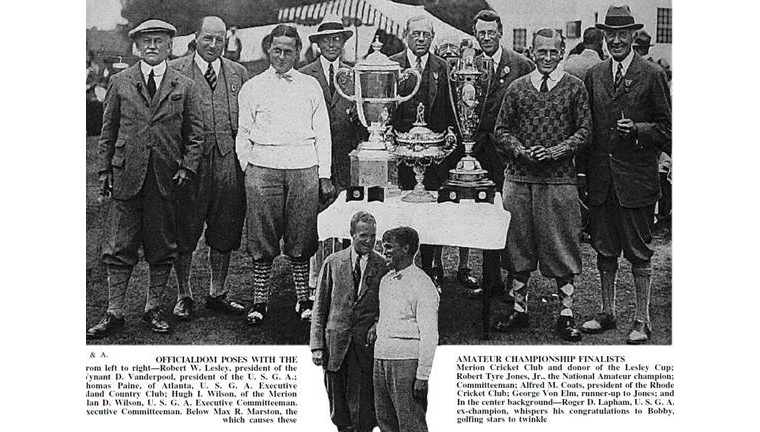

The last great hurrah for Hugh Wilson took place in September of 1924, when the US Amateur was again played at his beloved Merion East course. Photos of Wilson taken during the event show a tall, gaunt man, who appears happy and proud but with eyes expressing a certain weariness, as if the years of fighting physical afflictions were beginning to take their toll. In the tournament, wunderkind Bobby Jones absolutely devastated the U.S. Amateur field, and won the final decisively from George Von Elm by the lopsided score of 9 and 8.

Hugh Wilson dies

In one of his last letters to Oakley, Wilson complains of feeling like a “boiled owl”. A subsequent letter late January from his brother Alan indicates that Wilson’s situation is dire, and that his kidneys are failing.

In the 25th year book of the class of 1902 at Princeton, the following synopsis was written; “The knowledge of golf courses that he possessed came from an intensive study of the famous links of Scotland and England. He planned the course of the Merion Golf Club and the City Golf Course at Cobb‘s Creek. He was active in the construction of other courses also. At the time he was stricken ill he was working on the Marble Hall Golf Course, near Barren Hill, an unfinished public course.”

Hugh Wilson died on February 3rd, 1925, at the young and promising age of 45. It is difficult to imagine how he might have packed more activity into those short years, or how he could have been more valuable to helping advance the nascent game of golf in this country.

The Green Committee of the USGA eulogized him as follows;

It is with profound sorrow that we announce the death of Hugh Irvine Wilson, which occurred on Tuesday, February 3. He was a member of our Advisory Board, and in a large measure was responsible for the formation and success of the Green Section of the United States Golf Association. He was properly considered one of the best-informed men in the country on problems relating to the construction and maintenance of golf courses. Not only did he have a wealth of practical, first-hand experience, but he was also a close student, and in his research work he visited the principal course abroad in seeking complete information. Probably no one has been consulted more frequently by those interested in his work. His passing represents a distinct loss, not only to the Green Section but to golf interests everywhere.

But next to his beloved family circle, the largest measure of loss and grief will fall upon those who have had the privilege of his personal acquaintance and good fellowship. He was endowed with traits of character which set him apart. His modesty, cheerfulness, and genuine unselfishness endeared him to all who knew him. The feelings of his friends passed the bounds of admiration and amounted to downright affection. No one went to him for counsel or advice who came away empty handed. From the time he was a young man until the day of his death he suffered from physical handicaps which periodically brought him much pain and distress. He succeeded in keeping his personal tribulations from his friends, and showed them only a cheerful, helpful disposition such as is possessed by but few men. When he was consulted for advice, he had the happy faculty of giving it in a way that made you feel that he was favored by the call. His charity was of the kind that you would expect from him. Not only was he willing to help in a material way, but he showed a thoughtful consideration with regard to the comfort of those in distress, which made his benefactions the more acceptable.

The mature results of his studies in golf architecture are embodied in the East Course at Merion, which was remodeled under his direction in 1923-1924. It is safe to say that this course displays in a superb way all the best ideas in recent golf architecture along the lines of its American development. For a long time to come the Merion course will be a Mecca to all serious students of golf architecture.

It has been said that “a prophet is never without honor save in his own country”, but this was not true of Hugh Wilson. In Philadelphia, where he lived and worked and played, were his closest and most affectionate friends. Of few other men can it be said more truthfully that “none knew him but to love him, none named him but to praise.”

His loss represents a big gap in a very wide circle, bu the leaves behind him a precious heritage of high regard and affectionate memories of kindness and helpfulness to his fellow-men.

At Wilson’s funeral, caddies young and old from Merion flocked in attendance to pay their respects, and laid violets on his grave. Wilson’s life work had energized and expanded the game in Philadelphia and beyond, not only through the development of wonderful private golf courses for the elite, but perhaps more lastingly, through the thousands of common citizens he helped introduce to the game with his efforts to promote public golf courses in the city.

Wilson’s Architectural Legacy

Years after Wilson’s death, George Thomas, who created such gems as Riviera and Bel-Air on the west coast, wrote; “I always considered Hugh Wilson of Merion, Pennsylvania as one of the best of our golf architects, professional or amateur. He taught me many things at Merion and the Philadelphia Municipal (Cobb’s Creek) and when I was building my first California courses, he kindly advised me by letter when I wrote him concerning them.”

Hugh Wilson always preferred to let his architectural work speak for itself, and in that regard we are fortunate that most of his architectural work survives in fine fashion, with all of the courses where he worked still in existence. Certainly the courses at Merion still bear much of his stamp, but one wonders what Wilson would have thought about recent efforts to wring every last bit of yardage and to narrow fairways to slender ribbons through swards of deep rough as a defense against the best players. Wilson’s work also reflects a penchant for heavily sloped greens that reflected their natural surrounds so it’s likely he may have been concerned that modern green speeds would require them to be leveled, as the twelfth and fifteenth greens at Merion have been in recent times.

What little Wilson did say or write about architecture may provide some insight; “Hugh Wilson, who built the two fine courses at Merion believes every club would have better putting greens if it were not for the craze for lightning-fast greens. The reason why it is necessary to seed the greens every year is that excessive cutting prevents the grass from seeding, and it is necessary each year to put seed into the green. He says clubs would be much better satisfied if the grass on the putting greens were allowed to grow a little longer instead of having them like the surface of a billiard table.”

Certainly Wilson’s career shows he was not averse to evolving golf courses to reflect changing needs, but one senses that he would also recognize that there are practical limitations of acreage and cost that should be considered. In that regard, as a man who worked to fit great golf holes on some tight properties, it is very possible that Wilson would have agreed with his friend George Crump, who argued in 1917 for a standardized golf ball; “Golf Clubs cannot afford to construct expensive courses and then have all that work undone by a golf ball that anyone can buy….unfortunately, the golf ball makers each year are turning out new balls that can be driven further…if it keeps up, we shall have to change all our bunkering to suit the new ball, or else bar certain balls from being used. No club would care to do the latter, yet the expense of re-bunkering a course would be tremendous. If even the poorer players can discover a ball that can be driven two hundred yards or more we will find that all our bunkering has gone for nothing, and the three-shot holes will be easy two-shot affairs, and the two-shot holes nothing but a drive and a mashie (wedge) approach. In addition, none of the traps over which we have spent so much time would longer server their purpose.”

Wilson often worked in collaboration with others, seeking advice from experts, and sharing freely when he became an authority, as well. In today’s competitive architectural world, such methods likely seem quaint, yet the very collegial methods employed by Wilson and others of the time served to create some of our finest courses that have stood the test of time. Likewise, the idea of first creating the basic shell of a course, which then would be built up over time through the addition of features and hazards as play was observed and studied would be very expensive, if not completely impractical using today’s construction and irrigation methods.

However open Wilson was to seeking and heeding advice, it also seems that he was the ultimate decision maker at Merion. Max Behr, writing in “Golf Illustrated” in December 1914 stated; “By far the best work in this or any other country has not been done by committees but by dictators. Witness Mr. Herbert Leeds at Myopia, Mr. C.B. Macdonald at the National, and Mr. Hugh Wilson at the Merion Cricket Club. These dictators, however, have not been averse to taking advice. In fact they have taken advice from everywhere, but they themselves have done the sifting. They have studied green keeping and course construction as it was never studied before. And they have given the benefit of their studies to the world at large.”

Perhaps Wilson’s most lasting architectural legacy and one most worthy of study and emulation today was his pioneering work in combining naturalness, the blending of artificial construction seamlessly into the surrounding landscape, with the creation of golf holes that are fun for everyday play, where recovery is always a possibility, and that are adaptable to stringently challenge top players in competition.