Walter J. Travis “Dropped” at National Golf Links of America

Truth or Travesty? (Part Two)

by

Mike Cirba

April 2018

After winning his second consecutive United States Amateur tournament during the fall of 1901, Travis began to think more about the state of the game in America. Imbued with newfound knowledge and exposure to the great courses abroad the previous summer, the analytical side of Travis began to mentally explore what he saw as fundamental differences that largely accounted for both superior courses as well as superior golfers on the other side of the pond.

This exercise eventually translated into an article for Golf magazine titled simply, “Hazards”. In the piece Travis railed against the American penchant for platform flat greens and tees, shallow cross bunkers crossing the fairways at rote intervals, ramrod straight golf holes, and general malaise in thinking, creativity, and naturalness. Instead, Travis argued that interesting and thoughtfully placed bunkers placed generally along the sides but also towards the desired line of play brought interest, intrigue, challenge, and a sense of adventure to a round of golf, particularly for the better player. Travis felt American courses were too “dumbed down” in a condescending way, often to please the vast majority of club members who were not proficient in the game yet whose egos wouldn’t permit them to face a real challenge lest their ineptness be on full display. Travis felt that only by providing suitable challenge for all players would golfers be forced to improve, leading to an overall greater enjoyment for everyone. However, that is not to suggest that Travis was a penal architect; in fact, just the opposite. He believed that soundly designed courses provided the handicap man with safe, albeit indirect avenues of play but that same duffer could risk taking the more challenging route and dare punitive hazards when feeling his oats.

He wrote; “Speaking by and large, our courses here are not nearly so difficult, in respect to hazards, as those in Great Britain; nor, it may be added, has the game reached the same standard; and until we reach the approximate level of the one we can hardly hope to do so of the other… A really good course, before it can be unprejudicially pronounced as such, must abound in hazards – and good courses develop good players.”

“…Generally speaking, while we have not nearly enough bunkers, there is too much of what we do have. The material is there, but it is not scientifically applied. Let me endeavor to exemplify my meaning. Take, for instance, the regulation bunker for the tee shot. This almost invariably stretches across the entire width of the green. Instead of this, I should put in one, irregularly outlined, of about one-third the width across, leaving clear spaces on either side for the shorter player who cannot comfortably carry it, and from twenty to forty yards further on – according to the distance of the first bunker from the tee – hazards of nearly equal size on either side of the course to catch a pulled or sliced ball, as the case may be…”

“…The player carrying the first bunker would have the advantage of practically a clear and unobstructed approach to the green while the more timorously inclined or shorter player could play safely to the side, only, however, to be forced to negotiate the second bunker on his next shot.”

“Hazards arranged somewhat upon the lines indicated rather than slavishly following the system adopted on the great majority of our courses, would, I think, make the game vastly more interesting and more provocative of better golf all around.”

It is insightful to note that this was in 1902, almost a decade prior to the opening of National Golf Links of America, at a time when most of the courses in America at the time, including Macdonald’s vaunted Chicago Golf Club, and Devereux Emmet’s Garden City Golf Club featured much the same type of flat greens and cross bunkering that Travis criticized so evocatively in his article. What Travis was describing as a more creative and inspirational alternative is what we know and take for granted today as “strategic golf course architecture”, yet at the time Travis was writing these were no less than revolutionary ideas in America.

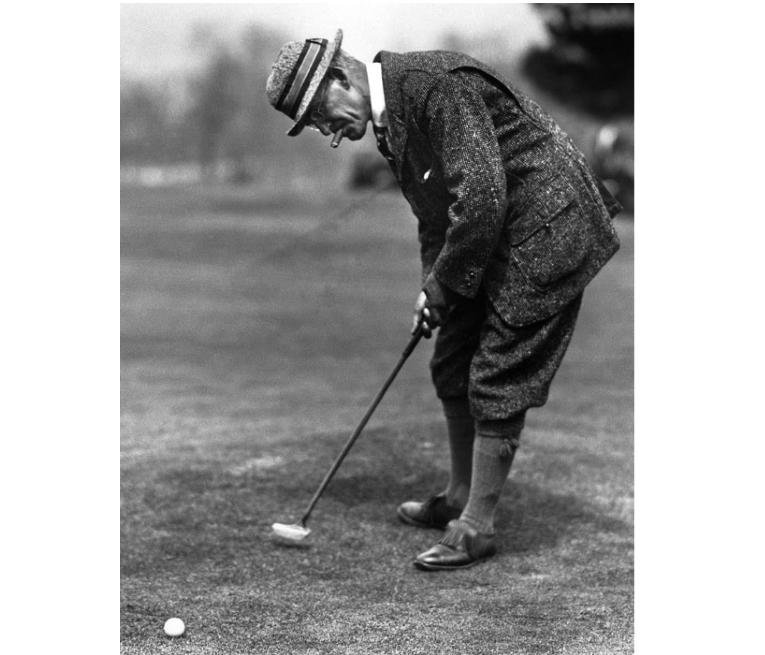

Travis’ embrace of innovation extended beyond golf course architecture and as he sought to perfect his game and seek any advantage Travis thoughtfully considered unconventional equipment, evidenced the previous year by his early adoption of the Haskell Ball. C.B. Macdonald wrote in his 1928 book that Travis first used the center-shafted “Schenectady” putter during the 1904 British Amateur but it is today known that he was given one by Devereux Emmet in the fall of 1902 and that he used one during the U.S. Open that year when he finished second. Another version had him bringing one back from his 1901 visit to Great Britain, as this November, 1902 Brooklyn Daily Eagle article details;

Despite having turned 40 years old early in 1902, Travis was at the zenith of his competitive career. However, traveling to Chicago for the 4th U.S. Amateur tournament held there within an eight year span, Travis was defeated by Chicagoan Eben Byers in the quarter-final round at the Glen View Club. The match was hotly contested and well played by both men.

Despite having turned 40 years old early in 1902, Travis was at the zenith of his competitive career. However, traveling to Chicago for the 4th U.S. Amateur tournament held there within an eight year span, Travis was defeated by Chicagoan Eben Byers in the quarter-final round at the Glen View Club. The match was hotly contested and well played by both men.

Later that year, playing in his first U.S. Open at his home club at Garden City, Travis finished second which was the best showing of an amateur in that tournament to date, a record that would stand for over the next decade until Francis Ouimet beat Vardon and Ray at Brookline.

In November of that year President Robertson of the USGA appointed Charles B. Macdonald, Herbert Windeler (of Brookline) and Walter J. Travis to a committee to study the Rules of Golf and make any suggested revisions. Macdonald evidently held sway with both the content and the tone of their report, which began;

“In accordance with the Resolution passed at the last meeting…we, the undersigned, beg to report that we have given the matter of the new rules our most earnest consideration and are unanimously of the opinion that it is inadvisable to make any changes solely in order that the game in this country may be played under exactly the same rules as are operative in Great Britain.”

The report then listed a series of “opinion(s)” with suggested rules that the R&A might consider for adoption, a number of which dealt with conditions more likely to be experienced in the United States (i.e. “casual water”) than in Great Britain.

One particular rule that still bristled Travis at the time was the broad definition of “amateur”, or more precisely, the various lists of general offenses that could lead to charges of professionalism. Earlier that year charges of professionalism surfaced again, in a detailed article by one E.G. Ryan in “Golfers Magazine”, titled, “Is Walter Travis An Amateur?” that faulted Travis for accepting free clubs and having his name associated with promoting various golf related products.

Ryan reproduced a letter that Travis had written to professional John Reid in Philadelphia in 1900 where Travis asked Reid to provide him a couple of clubs free of charge in the hope that additional orders would follow given Travis’ prominence. Repeating the Florida trip charges, Ryan listed a litany of other supposed sins where Travis permitted his name to be used in advertisements, with the implication that it was a clear pay scheme. Ryan concluded, “When an ‘amateur’ champion deliberately offers to tout for a clubmaker the writer thinks it is high time to acquaint genuine amateurs with the ‘plugging’ methods of an individual who is supposed to be the ne plus ultra of the American amateur golfing world.”

Travis again did not respond to the charges directly, but wrote an editorial later that year in “Colliers” magazine concerning a proposed International golf match between the best amateurs of Great Britain and the United States. Recognizing that most of the British amateurs might require some additional monies to make the voyage and stay in America for several weeks which would leave them open to charges of professionalism, Travis wrote, “Already there is some talk of arranging for the visit of a team of British amateur golfers this year, a consummation devoutly to be wished. But for the somewhat strained, not to say quixotic, definition of an amateur by the present administration of the United States Golf Association, there is no doubt that an international team match would before this have been definitely arranged. As it is however, this ruling of the USGA may possibly bar the way to any such meeting.”

Earlier that year, C. B. Macdonald had travelled abroad determined to validate his new vision for an ideal golf links made up of exceptional holes modelled after the best holes abroad. He later wrote;

“I concluded it was feasible if I could only find a property adapted to it and then find a backing to carry it out. I determined to try it, and for the next four or five years I worked to that end…”

In 1903, having won a rematch against Eben Byers to win his third U.S. Amateur in four years at Nassau Country Club, Walter Travis was again at odds with the USGA who had scrapped the qualifying rounds in favor of starting all 140 players at Match- Play. Travis wrote, “I thoroughly believe in the retention of the preliminary round. No man should be considered a finished golfer, certainly not a champion, unless he can combine reasonable proficiency at score play with high abilities as a match player. Moreover, it is essentially an American idea, and a very good one, and its abandonment now would be a tacit admission that we have seen the error of our ways, which I, for one, am not prepared to admit at all.”

During this period, Walter Travis continued his involvement in the design of new golf courses. In the fall of 1903 Walter Travis laid out an ambitiously conceived course for the Lackawanna Railroad in the Pocono Mountains. Travis apparently designed eighteen holes, but only nine were ever built (Author’s Note – Sadly, the golf course closed in 2013). In November of 1903 the Wilkes Barre (PA) Record and Wilkes Barre Times reported the following;

In June of 1904 the Philadelphia Inquirer reported on the creation of the new club;

While extolling the virtues of the great courses of Great Britain since his 1901 visit, and holding a dutiful respect for the great British golfers who had dominated the game up to that time, and having joyfully hosted and competitively participated in the first International Golf Matches of 1903 when the Oxford and Cambridge Golf Society of Great Britain toured the best United States courses in a series of competitive matches, with the finale at Travis’s beloved Ekwanok, there is no way that Travis could have been prepared for the unsportsmanlike treatment he would receive after arriving in Great Britain to compete in the 1904 British Amateur.

Through his prior dealings with many of the British sportsmen he felt encouraged to make the voyage, and he loved the course at Sandwich where the year’s event was being held. His good friend Devereux Emmet was in England that spring and wrote to Travis, “…I hear you are coming over to Sandwich to have a try at the Amateur Championship. I hope this is true. I will be there to root for you … Let me know where you are staying in Sandwich and when you go there.”

Travis brought a small entourage of friends and family across for support and upon landing was greeted with disdainful avoidance. Finding a friendly game with British amateurs proved elusive, and although many of the professionals like Vardon and Taylor were welcomingly warm, the amateur contingent viewed him warily as a foreign interloper. Travis had trouble finding both a room to stay nearby as well as a locker, having to change clothing in a public hallway. Perturbed, Travis declined an invitation to dinner, further fueling the distrust on both sides. Travis was given a caddie who seemed woefully inexperienced, sight-challenged, and generally incompetent and when he protested, was told that nothing could be done.

Travis used those perceived slights as fuel for his competitive spirit. “A reasonable number of fleas is good for a dog. It keeps a dog from forgetting he is a dog. Of course there had been present before a determination to win, but that was as nothing to the now steel-clad resolution to do so.”

Armed with a Schenectady putter suggested and loaned by his friend Edward Phillips when Travis was struggling on the greens during practice rounds, Travis mowed down a contingent of notable British amateurs including Harold Hilton, Horace Hutchinson, and in the finals eliminated Edward Blackwell.

The awards ceremony was a travesty. Lord Northbourne who presented the cup gave a long-winded speech on the glories of British history, extolled the virtues of the British golfing amateurs, and barely mentioned Travis in congratulations, concluding, “Never, never since the days of Caesar has the British nation been subjected to such humiliation, and we fervently hope that history may not repeat itself.”

Travis made a brief, gentlemanly speech in response mentioning the fine play of his competitors, and then perhaps understandably flustered simply stated, “I am hopelessly bunkered. I pick up my ball.”, and left the dais.

Back home in America Travis was treated as a conquering hero. The New York Times exclaimed excitedly, “Travis may now justly be called the amateur golf champion of the world.”

Retrospectively, Horace Hutchinson’s comments in defeat may have foreshadowed future events that would eventually drive a wedge between Great Britain and the United States golfing bodies, and consequently between Walter J. Travis and Charles B. Macdonald;

“Everyone is asking – have you seen the American who is putting with an extraordinary thing like a croquet mallet and putting extraordinarily well? With that long black cigar in his mouth and his deliberate methods, including the practice swing before each stroke, he is a rather hard man to play against”, conceding, “I think critics make a mistake who say he is not a first class golfer” (the reader should note that practice swings were not customary in British golf and were actually banned a few years later.)

In 1904, Charles Macdonald made another trip abroad to study golf courses in preparation for planning his “Ideal” course, “reflecting on the “whys” and “wherefores””, as he termed it. Later that year he prepared and mailed a subscription agreement, soliciting $1000 per individual to become a Founding Member of his proposed “National Golf Course” that would be “comparable with the classic golf courses of Great Britain and Ireland.”

In conclusion, he wrote, “Mr. Charles B. Macdonald will take charge of this matter and associate with himself two qualified golfers in America, making a committee of three capable of carrying out this general scheme (bold for emphasis mine). In the meantime you are asked to subscribe and leave the matter entirely in his hands.”

Meanwhile, back in Garden City there was an organization called the Midland Golf Club that had formed in 1899 and played on a relatively short nine-hole course built by the Garden City Company just south of Garden City Golf Club. The course was open to guests of the Garden City Hotel as well as roughly 50 early members that included both Walter Travis and Devereux Emmet. Very quickly this land became prime real estate and by 1904 the Club and Garden City Company (some of whom were synonymous) were considering their options that included building a new golf course a bit further from Garden City Golf Club in the eastern outskirts of town. The following New York Globe & Commercial Advertiser article from May of 1904 shows both Travis and Emmet collaborating on the design, although it wasn’t until 1906 that a new course was actually built in a different location. More information about that event will be introduced later.

At this time despite some periodic dust-ups over particulars of the rules, it seems that Walter J. Travis and Charles B. Macdonald were actually close friends. In early 1905, Travis and Macdonald (with Mrs. Macdonald) and A.L. Norris (with Mrs. Norris) travelled on a golf vacation to Bermuda. (It is not known whether Mrs. Travis attended.) An account of the week’s play is indicated in this March, 1905 New York Tribune report. Please note the last paragraph regarding Travis’s disinclination to defend his British Amateur title;

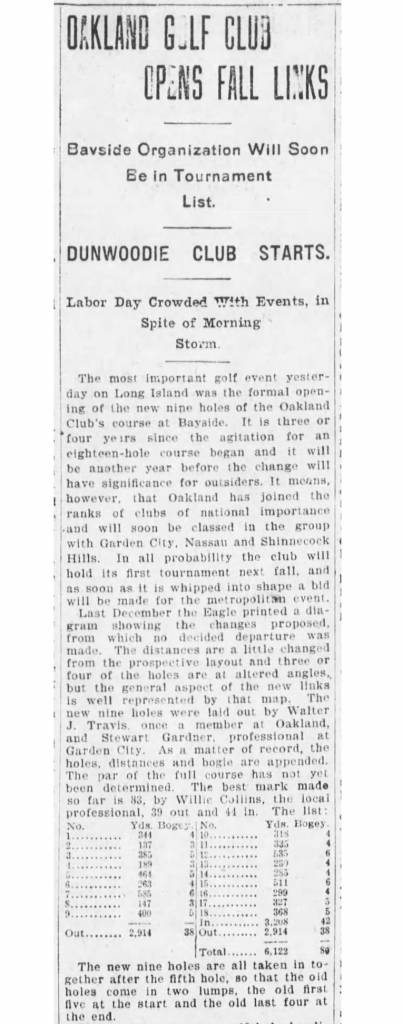

During the latter part of 1905, Walter Travis (along with Garden City professional Stewart Gardner) designed nine new holes for Travis’ former home club, Oakland Golf Club. The expanded eighteen hole course opened in the fall of 1906 to solid acclaim.

In the 1905 U.S. Amateur played at Chicago Golf Club both Travis and Macdonald made it to the match play round before losing; Macdonald in the first round to eventual champion H. Chandler Egan, and Travis in the third round to H. C. Fownes, Jr. of Oakmont.

The year 1906 was possibly the most eventful and impactful one in golf course architectural history.

Early in the year Walter Travis was again at Pinehurst during the winter. For some years he had tried to convince Leonard Tufts, owner of the resort to toughen the infrequently played #2 course that had been laid out five years prior by Donald Ross. Tufts, thinking perhaps his vacationing golfers did not need to be subjected to such a degree of stressful challenge had balked, but over time Travis convinced him to try it.

Travis later wrote, “I knew the changes I had in mind would result in a big uproar from the start, and I didn’t feel like soldiering the whole responsibility. So I suggested that Donald Ross and I should go over the course together, and without conferring, each propose a separate plan. I knew what the result would be.”

“For some time I had been pouring into Donald’s ears my ideas; in point of fact, I had urged him to take on the laying out of courses, as with the certain development of the game a fine future was assured for one having a bent in this line. In those days Willie Dunn had ceased to figure and his successor, although credited with laying out hundreds of courses all over the country, really had no genius for the work. Donald heeded my advice … and golf has been tremendously benefited by his many fine creations since.”

“… So I felt quite certain of what would happen. Donald and I were a unit. And the course was bunkered accordingly, with one exception and that was on the twelfth hole. Here I planned three avenues of play, down the middle, narrow with a big bunker 180 yards from the tee, leaving a clear second to the green. It was quite revolutionary in those days, such a big carry, but it was decided to construct the holes as outlined. When he came to it, however, Donald’s courage failed him; he weakly compromised by making a straightaway affair of it, with a bunker at the right some 160 yards from the tee, which didn’t mean anything.”

“… What was the result of this stiffening up? Men who ordinarily did number one course in the lower 80s tackled number two. Up ran their scores into the high 90s, possibly over the century mark. Disgusted, they emphatically declared they were through – it was a course only for experts. But – and here lies the lure of the game, challenging the player to match his skill against difficulties – a little sober reflection, pique, never-say-die, or something or other rushed those same men over to number two the first thing the following day … And at it they kept day after day. Whereas the problem had been how to get players from number one to number two, now a new one presented itself – how to get them back to number one – which was finally solved in a way by stiffening up number one.”

As the late Bob Labbance pointed out in his Travis biography, “The Old Man”, both Donald Ross and Leonard Tufts were quite alive and well when Travis wrote this passage in a 1920 article in “American Golfer” and it should be noted that neither sought to refute it.

Travis also had strong architectural opinions back home at Garden City Golf Club in New York, where he had been a member since 1900. His good friend Devereux Emmet had originally designed the course back in 1897 and like nearly all American courses of the time it featured many cross bunkers and generally flat greens. What it did have as its chief attribute was a solid routing on wonderfully sandy, almost links-like soil and turf on what was known as the Hempstead Plain. Still, given the state of golf course architecture in America at the time Garden City was generally believed to be one our very best courses; one worthy of hosting national competitions as it had by that time hosted both the US Amateur and US Open tournaments.

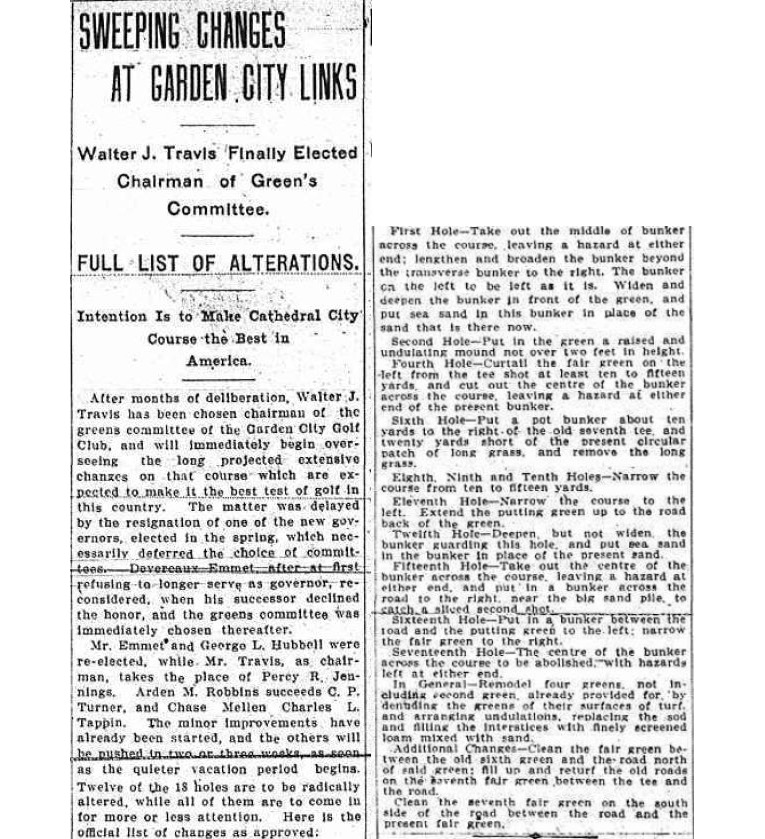

Given that prestigious history to date, one did not make criticisms of such a course lightly. For years Travis would tell anyone and everyone who would listen at the club (including Emmet, and likely C.B. Macdonald who was a fellow member) how the course could and should be improved. After his 1900 victory at Atlantic City Travis argued for the course to be lengthened and it was for the 1902 U.S. Open. In the spring of 1906 he penned an article for “Country Life” magazine that detailed extensive proposed changes, primarily to the bunkering and flattish greens. While attempting to be politically correct in citing it as probably the best course in the country besides Myopia, Travis then proceeded to list his litany of proposed changes he felt would elevate the course to a much higher standard of interest and competitive challenge.

It isn’t difficult to imagine that such an article and the opinions it offered weren’t the source of much discussion and even possibly dissention within the club. While in retrospect we can easily see the merits of what Travis proposed (and eventually implemented) but at the time these ideas were still quite revolutionary to American golfers.

One also has to wonder about the dynamics between Travis, Emmet, and Macdonald at the time in terms of their own opinions about the course and the value of Travis’ suggestions. Again in retrospect, it seems quite believable that both men were quite supportive, as it wasn’t long before both men were employing Travis’ philosophies at courses where they had a free design hand. Whatever the case, in June of 1906 Walter Travis was elected Chairman of the Green Committee at Garden City, and the proposed changes he had advocated were approved.

Travis was not only inspired by the great links of Great Britain but also was greatly impressed by Herbert Leeds efforts at Myopia Hunt Club, near Boston, which he considered the best course in the country. In an article for “Country Life” he wrote; “As a whole it is beyond criticism. No two holes are alike, and there is not a single hole which is any way unfair or which does not call for good play. The charm of the course lies in its diversity, the excellence of the lengths of each hole, the physical characteristics, the well-conceived system of hazards, good lies throughout, tees better than most putting greens, and putting greens, mostly undulating, which are the finest in this country and equal to the best anywhere in the world”

He continued to preach his radical (to America, at least) brand of architecture in every available forum, including various writings for publications and conversations with friends.

As mentioned earlier, in 1906 a new golf course was built by the Garden City Company, with George L. Hubbell as General Manager and the aforementioned Midland Golf Club planned to move there. Initial reports credited Devereux Emmet and Hubbell with the design of the golf course, but when the course opened in the fall of 1907 the President of the Garden City Company mentioned that it had been “laid out by the Garden City Company” and other subsequent reports like the following one from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in 1910 can be read to credit both Travis and Emmet with planning the course. On opening day in October, 1907 Walter Travis was asked to drive the first ball, which was then carefully preserved for posterity.

There seems little question that Travis’ good friend Devereux Emmet was the principal force with Hubbell in the creation of the Salisbury Links but it’s also difficult to imagine as Captain of the Garden City Golf Club and Chairman of the Green Committee that Walter J. Travis would not have been involved in the proceedings with the new public course being built by his friends a mere ten minute stroll away. Also recall that the new course planning two years prior had both Travis and Emmet collaborating on the design of the course that was to be used by their Midland Golf Club.

Indeed, Travis was so delighted by the golf course that he wrote a lengthy article for “Country Life” in early 1908 extolling its multiple options of play for weaker and stronger players, the variety and interest of the holes, the undulating, diversely-sized and shaped greens, all of those revolutionary things he’d been championing to anyone who would listen since 1901 when he returned from the British Isles as somewhat a lone voice in the American wilderness. He and Emmet were now clearly in lockstep.

Travis went so far in some accounts to say that the new course had the potential to even exceed neighboring Garden City Golf Club, most likely in an effort to spur his home club to implement further architectural enhancements he thought would benefit those links . (Note – A highly modified version of Salisbury Links still exists today as the private “Cherry Valley Club”.)

It should be noted that the “Walter J. Travis Society” does not believe that there is sufficient contemporaneous evidence of Travis’ design involvement to list Salibury Links as one of his courses at this time. While not entirely conclusive in terms of origin, it seems this speculation may be somewhat moot and misses a larger point. What is undisputable is that at the opening of the new course both Travis and Emmet were in close agreement as to what constituted a soundly designed golf course and those guiding principles of eliminating cross bunkers and instead fashioning “scientific bunkering” to tempt the better player, creating multiple avenues of play to accommodate all classes of golfers, and providing varied and undulating greens were the same ones being advocated by Travis since his 1901 Great Britain visit.

This is not to conclude that Emmet wasn’t similarly inspired by what he observed during his frequent travels abroad. However, it seems from the historical record that Travis was the first to take the lessons of the great historical links abroad, and the words and writings of learned men like John Low and interpret and codify them for an American audience in his writings and then sought practical applications for the realization of those principles on golf courses in the states. He also preached these innovative ideas to his friends and contemporaries at every opportunity.

It is interesting to note that at no time during this period did Travis either mention or promote his design efforts at those courses were he clearly did architectural work between 1897 and 1907, as documented herein. This omission was despite the fact that he wrote extensively for several publications during this period and authored a number of golf-related books. The only exception were those changes he was advocating for at his home club of Garden City, which would have been understandable and acceptable in his role as Captain of the club and Chairman of the Green Committee.

Although this may seem unusual today, when one considers that the USGA rules of “Amateur Standing” were so broadly construed at the time, it’s easy to see how perhaps a comped stay at the Equinox Hotel in Vermont, or rail transportation provided to the Pocono Mountains gratis, or just the loose nature of some of the financial arrangements of these large undertakings could bring one under suspicion and charges of, sin of sins, professionalism! It is also a fact that almost every golf course in America at this time was either laid out by a foreign professional or, a rudimentary affair by club members themselves to bat some balls around a field. Laying out a golf course was largely viewed as a working man’s endeavor, after all, and whether Travis felt he needed professional “cover” to maintain his unsullied amateur status at this time through collaboration with professionals like John Duncan Dunn, Stewart Gardner, Thomas Bendelow, or Tom Anderson is certainly a very real possibility.

Travis was attempting to walk a very fine line as an amateur with his unprecedented attempts to transform American golf course architecture at a time when nearly all “design” work was done by foreign “professionals” who were believed to have an innate talent for the work by virtue of their birthplace and prior exposure to the game abroad. This break from accepted tradition and even class structure was noted in the June, 1906 Brooklyn Daily Eagle” article below. (Author’s note – the article neglects the prior amateur work of men like Macdonald at Chicago, Emmet at Garden City, and Leeds at Myopia but each of those men came from an unassailable patrician background and Travis by this time had already been charged in the press with prior offenses.)

One also needs to consider that Walter Travis at this time was the greatest amateur golfer in the world and his competitive goals required him to stay an amateur. Not that there weren’t professional tournaments, but those were viewed with much less prestige and even dignity. By now Walter Travis was working for a brokerage firm in New York City, a gentleman about town, and his standing in golf needed to reflect that.

The question of amateur/professional as related to golf course architecture wasn’t fully settled until 1916, when it was determined that it was only the acceptance of money specifically for laying out a golf course, and not just the perimeter associated activities that deemed one a professional. By that time in his life, Walter Travis had given up on his competitive career, and had quit the business world, and became a professional golf course architect for the remainder of his life, along with his related golf and golf publication activities.

But the fact remains that by the end of 1906, Walter Travis had now been involved in the architectural design and planning of more golf courses and more progressively strategic golf courses than any man in America. He had studied the great courses abroad and had come back a convert and a zealot, and a preacher. His revolutionary ideas about eliminating what he saw as the evils of banal, rote golf course design and the elevation of architectural principles consistent with the great courses abroad had now gained broad acceptance from the American golf community (see April 1907 Buffalo Courier article below) and he would soon have a publication of his own to trumpet his strongly held opinions on these and other golf-related matters.

Finally, if the year 1906 hadn’t already been wonderfully eventful as a landmark turning point for golf course architecture in America, by year’s end Charles Blair Macdonald announced that he had located and secured some 200 acres of sandy wasteland in southeastern Long Island that he believed was optimal to build his dream of an “Ideal Golf Course”, and the die was cast.