Walter J. Travis “Dropped” at National Golf Links of America

Truth or Travesty? (Part Three)

By

Mike Cirba

May, 2018

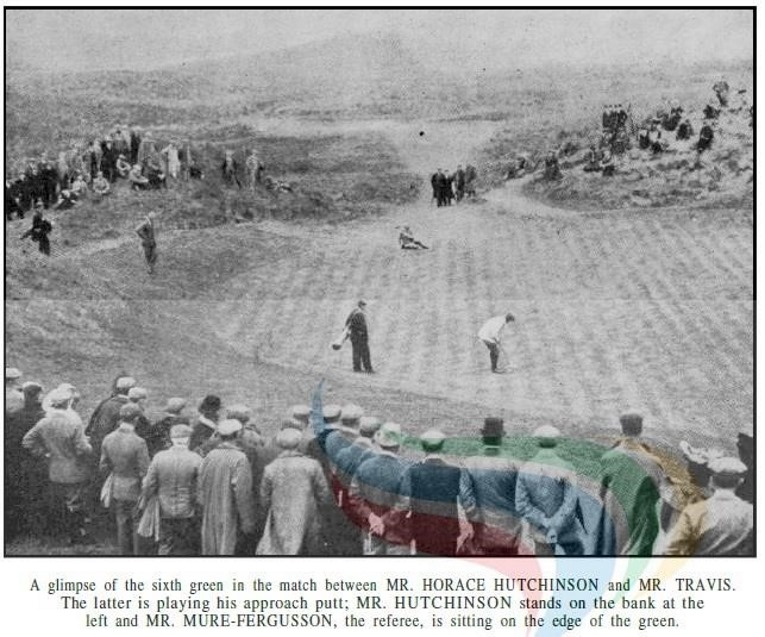

Walter J. Travis and Charles B. Macdonald seated next to each other in a group photo during the July 1910 National Golf Links of America Founders & Associate Members “Soft Opening” Tournament

In the spring of 1906, Charles B. Macdonald again traveled to Great Britain, this time focused on sketching the details of golf holes and features that he might want to duplicate on his Ideal Golf Links. During this time he was looking at three different sites but felt close to a deal. As such, he used his good friend Walter Travis as his American conduit to keep prospective founding members up to date with his activities and progress. This Pittsburgh Post-Gazette article from March 1906 outlined the plans, which included Macdonald spending the months until June of that year abroad in detailed study and recording.

Travis, back in the states working on the extensive course changes for the Garden City Golf Club that he, Macdonald, and Devereux Emmet called home at that time had arguably the most architectural experience in terms of intellectually challenging strategic design than any man in America. The fact Travis was also an amateur made him the obvious choice for Macdonald to collaborate with.

At that time, Walter Travis was also still at the height of his competitive powers. Incredibly, after winning 3 U.S. Amateurs and a British Amateur victory in the years of 1900-1904, he also was the medalist at that tournament each of the three years between 1906 and 1908, although he faded in later rounds. Even in 1910 at the age of 48, he won 8 out of 10 tournaments he entered during one period, usually playing against men half his age.

In the fall of 1906 Charles Blair Macdonald was able to close on 200 acres of what seemed a tangled mess of brambles to less visionary observers but Macdonald was looking for rolling ground contours, generally favorable sandy soil, and proximity to the water. The fact it abutted Shinnecock Hills Golf Club was probably a bit of annoyance to him, but here Macdonald rightly believed he could build his Mecca.

To accompany him in the work of designing and constructing the golf course, Macdonald chose the three men with the most experience in these matters in the United States. Walter J. Travis, Devereux Emmet, and Macdonald’s son-in-law H. J. Whigham were not only experienced with course design but also were intimately knowledgeable regarding the great courses abroad. Travis had taken things a step further with his writings and proselytizing of the gospel of strategic course architecture and “scientific” placement of hazards. The following snippets from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle and New York Sun articles in mid-December 1906 outline the anticipated next steps now that the property had been secured. Months of architectural planning were now anticipated with a hoped for start to construction in the spring of 1907.

The following syndicated article spoke of the experience and architectural knowledge of all of the men involved in the project.

The first few months of 1907 were spent planning the holes to be created on the rugged, overgrown Southampton site. At the end of April, Shinnecock veteran Mortimer S. Payne was hired to oversee construction. That month the following portion of an article by Walter Travis was published in Country Life about the course to be constructed at the National. You will note that Travis mentions that he’s already been to the site “a number of times” and each visit has revealed “additional charms” and “latent possibilities” and more opportunities for the creation of great golf holes.

Moreover the article mentions that Macdonald will still be soliciting input from some of the best minds abroad in the selection of holes to utilize but has also surrounded himself with men (like Travis) who not only are familiar with the best courses abroad but who have “a good deal of experience” with the details of course building in the United States.

Construction proved to be difficult. Macdonald later wrote about the site, “It abounded in bogs and swamps and was covered with an entanglement of bayberry, huckleberry, blackberry, and other bushes and was infested with insects.” Nevertheless, by September of 1907 it was reported in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle that the construction of all the greens had been finished and that the “committee in charge of the work” was particularly pleased with the Eden hole green, although they were already finding that they would likely need to raise the Cape Hole green as they sometimes found it completely underwater at high tide.

In late 1907 Walter Travis introduced another sweeping round of changes to Garden City Golf Club, adding a significant number of bunkers while planning to turn the 18th hole into a reproduction of the famous Redan hole at North Berwick, and was rumored to be considering replicas of other classic holes abroad. This was reportedly to provide a little “competition” to the National Golf Links which was still slated to open in 1909. It’s not known if those plans were altered (or possibly misreported) because the eighteenth hole as exists today is more often compared to the St. Andrews Eden hole, not the Redan.

While those changes were being implemented and 1907 turned into 1908, H.J. Whigham, Walter Travis, and Charles Macdonald were taking part of a bit of holiday fun and frivolity at Garden City Golf Club, with Whigham zooming around the course in under 50 minutes with Travis following on his bicycle.

Meanwhile, back in Southampton the project continued apace. Given the challenges of the site, construction work proceeded well into 1908 and on July 17th of that year the New York Herald posed an almost full-page article about the progress to date that included the following center photograph, seemingly indicating that Walter Travis was still part of the design/construction committee.

Of course, it might be arguable that this photograph may have been from a year or so earlier but the inclusion of a photo of Mortimer Payne and several photos of the holes in progress make it more probable all were taken during the same, more recent site visit.

The belief that Walter Travis was still fully involved with the evolutionary design and construction of the project in August 1908, almost 20 months after Macdonald initially secured the land, is buttressed with this snippet from an August 23, 1908 New York Tribune article that lists him as one of the men still involved in coming up with the design and construction ideas for the course that construction foreman Mortimer Payne was faithfully executing.

The article is notable in a number of respects that show it is not simply another retreaded article reiterating stale information. It mentions that nearly two years have elapsed since work began (in the late fall of 1906), and that articles of incorporation have been recently taken out on the “National Golf Links”, (which took place June 29th, 1908). It should be noted that previous to this time the course was originally to be called the “National Golf Course”, a subtle distinction that will be discussed later. It mentions that the building that was to be used for the clubhouse, the Shinnecock Inn, had burned down the previous spring and that a new one would be built either on the original Shinnecock Inn site or over near the Peconic Bay side.

Further, it discusses Macdonald’s “constant communication” with his friend Horace Hutchinson regarding the project, and mentions that amateurs Macdonald, Walter Travis, H.J. Whigham, and Findlay Douglas have all been contributing “suggestions and ideas” that Mortimer Payne has “carefully carried out”, and mentions Payne’s herculean work to effectively drain the swampy areas of the golf course. Clearly it seems the collaborative design/construction effort still involved Walter Travis at this time.

As an aside, it is mysteriously interesting that not a single contemporaneous mention of Seth Raynor’s role in the building of National Golf Links has been found to date. Why Raynor was never mentioned during construction and why Mortimer Payne was never credited by Macdonald after the fact is a source of speculation. What is known is that the construction and grow-in process took several years, with a number of notable agronomic failures (grass growing on the greens was referred to as “cabbage”). It took nearly three and a half years after construction began for the course to have its first soft opening for Founders in July of 1910, (the course condition being described as still rough at that time), and the course didn’t officially open until the fall of 1911, an almost five year odyssey.

In November of 1908 Walter Travis launched “The American Golfer” magazine. Travis had written extensively about golf for various publications during that decade but his new endeavor provided him with a public forum where he could pontificate on a broad range of golf-related issues.

In April of 1909, Travis happily reported, “The new course of the National Golf Links of America at Shinnecock Hills will be opened for informal play in June next. The formal opening will not take place until the season of 1910. Work has been progressing very satisfactorily and the course, even now, is in very good shape.”

The following month he wrote an extensive five-page article titled, “The Constituents of a Good Golf Course”, in which he laid out all of the elements of sound architectural and maintenance practices he’d learned to date. A number of passages are relevant to this discussion. Travis wrote, “Anyone who has seen Prestwick, or Sandwich, St. Andrews, or dozens of other natural golf courses in Great Britain, will readily recognize the ideal. Sad to say, we have nothing like it on this side – that I know of! The nearest approach to the real thing is the National Golf Links at Shinnecock Hills, just nearing completion.”

Later Travis writes, “It will, of course, be recognized that it is impossible within the limits of this article to do more than merely suggest in a broad, general way, the leading principles involved. But anyone who has played over the new course at Pinehurst will have had an opportunity of seeing how a course should be laid out on proper lines. Another fine example is the Salisbury Links at Garden City and soon, another, the finest of all, will be open for play, the National Golf Links at Shinnecock Hills.”

Given the way Walter Travis’ greens are still admired and even marveled at to this day, he wrote the following regarding greens; “SITUATION AND CONTOUR OF GREENS –Advantage should be taken of natural conditions most favorable to the location of greens, even at the expense, at times, of length of the hole. Certain places will at once suggest themselves as being most favorably adapted for greens, owing to their peculiar nature or environment. These should be made the most of. So far as possible, the natural contour of the ground should be preserved.(Author’s note – Shades of John Duncan Dunn!) Diversity is the great desideratum. Out of eighteen greens I would suggest three fairly flat, two or three gently sloping, one or two on the punch bowl order, two or three of the plateau type, and the rest more or less undulating. This, of course, applies more particularly to new courses, although old greens can be changed without any great amount of trouble, or expense. Out of the eighteen at Garden City, for instance, no less than seven have been altered more or less radically by the addition of undulations of a more or less pronounced character, and four have been changed by putting in mounds or ridges.”

In November of 1909 to perhaps bring the architecture of Charles Macdonald, and golf architectural thinking in America to that date full circle, Travis wrote; “David Foulis, the professional of the Chicago Golf Cub at Wheaton, Ill., has just paid a visit to several of the best courses in the East, such as the National Golf Links at Shinnecock Hills, L.I., Garden City, Myopia, and the Country Club, Brookline, Mass., having been commissioned by his Club to gather ideas in connection with the changes which are being made at Wheaton with a view to bringing it more into line with up-to-date courses.”

In 1910, Travis continued the praise and promotion of National Golf Links. In March he wrote,

“Immediately alongside is the new course of the National Golf Links of America, now nearing completion, with rare natural advantages in soil and contour of surface. Here no money or pains have been spared to make each and every hole the most perfect of its kind, and so far the results justify the belief that the course as a whole will easily be the best in this country, if not in the world … which we (bold emphasis by author) are quite aware is saying a great deal.”

That same month, Travis used his soapbox to settle some old scores. Travis penned a fully 19-page article titled, “How I Won The British Championship”, replete with a full accounting of every slight, real or perceived, that occurred to him and his traveling companions that week, an accounting of each and every match played, some marvelous photographs, and the British newspaper accounts of the matches in question. The list of the defeated read like a who’s-who of British amateur golf royalty at the time, including Harold Hilton, Horace Hutchinson, and in the finals long-driving Edward Blackwell.

Particularly stinging was a section on the equipment Travis used, perhaps implying that he could have beaten his opponents with virtually any implement of choice. Travis wrote, “I got going all right the following week in the practice rounds…but the putting was still the weak feature. Finally, the day before the Championship, Mr. Phillips, of the Apawamis Club, Rye, a member of our party, suggested I should try his putter, a Schenectady. It seemed to suit me in every way and I decided to stand or fall by it…”

“It may or may not interest those players who are wedded to a particular set of clubs to learn that after every match I would go into the professional’s shop and purchase one or more clubs. The result was that when I played Mr. Blackwell, of the original set with which I started, I had only two clubs, a mashie and a putter. All the rest were entirely new. As to the putter, it did excellent work during the meeting. I supposed that taking it all through my average would be slightly under two putts per green. In nearly every match I would run down two or three very long ones…But the putting on the whole was distinctly good. I have, however, on several occasions since…putted vastly better. The singular thing about that Schenectady which I used throughout the championship is that I have never been able to do anything with it since. I have tried it repeatedly but it seems to have lost all its virtue.”

The article was not well received in Great Britain, and the controversy led Harold Hilton to write a rebuttal piece the following month in “Golf” magazine titled, “The Facts Of the Case”, that began; “The cabled reports of Mr. Walter Travis’ revelations of his treatment over here as a competitor in the championship at Sandwich in 1904 have naturally been the cause of a great deal of comment amongst golfers in this country, and have not unnaturally been received with feelings of somewhat bitter resentment against the American ex-champion. As even if it were admitted that there is a certain substratum of justice in the opinions of Mr. Travis, one cannot but think that he has taken the trouble to rake up the existence of every petty grievance that he could think of, and by the art of inference, fashion them into horrible examples of lack of courtesy and hospitality on the part of British golfers.”

Mr. Hilton’s article was tame compared to some of the outrage expressed in the British press, most somewhat justifiably asking why Travis was airing these grievances nearly six years after the fact. Open wounds evidently took some time to heal, or perhaps Travis was somehow made aware of the fact that at that very time the R&A was looking into possibly banning the Schenectady Putter.

In any case, in May Travis’ American Golfer continued the war of words with the home of golf, this time directed to the R&A. Written under the pseudonym, “Bunker Hill” was the following; “This man from the west intended to pay St. Andrews another visit. He would like to put his head through the door at one of the sessions of the rules committee, if they ever held one, like Horace Hutchinson’s shock-headed Irishman and ask a few questions. Ireland never had been given a course in the rota for the amateur championships though it was destined to have the best links in the world if it had not one of such ranking at the present. It might not be a bad idea to throw Ireland a rope and tow the island nearer to the United States. The St. Andrews committee, to his mind, had not quite waked up to the fact that it was acting for the whole world. It had paid a half compliment to the United States by selecting a Scotsman resident here as a member of the rules committee but some day it might learn that Americans were quite able to understand the rules of golf and to help in their revision from time to time.” (author’s note – he was referring to Charles B. Macdonald, who had been appointed by the R&A on the recommendation of Horace Hutchinson to represent the United States in a non-voting role on the Rules Committee.)

“Also, the time was rapidly passing, and in the instances of at least two links in the country, had not been dependent upon advice from Great Britain as to how to lay out a golf course which would compare favorably with the best in the old world.” (author’s note – likely to be referring to Myopia and Garden City, or possibly the new Salisbury Links)

“To tell the St. Andrews committee a few truths might result in a less conservative attitude to golf by that body and work its way into the brains of the editors of English golfing papers who whenever they thought of an extravagant or an absurd happening on a golf course promptly credited it as taking place on some American course. They had no American correspondents and were 15 years at least behind the times as far as golf in the United States was concerned.”

In May of 1910, the Rules Committee of the R&A did in fact ban the Schenectady Putter as part of a broad decree against center-shafted, “mallet-headed” equipment. As the late Bob Labbance pointed out, it is unknown whether this was purely coincidental timing or based as many believed as a slight to Walter Travis and subsequent diminishment of his 1904 accomplishment as a vengeful response to his March article. It certainly didn’t help that Edward Blackwell, who lost to Travis in the 1904 finals, was the one who seconded Captain Burn’s motion on the ruling. In any case, the ham-handed decision and the way it was summarily communicated led to great dissatisfaction throughout American golfers in general as the putter had become very popular in the States since 1904, with almost 50% of American golfers using some form of the club. Ironically, it had also become greatly popular in Great Britain.

In June, Walter Travis wrote the following in American Golfer in response to the ruling; “The embargo against mallet-headed clubs bears all the earmarks of having been railroaded through with indecent haste. The whole affair was sprung as a surprise, on both sides of the Atlantic, so much so, indeed, on this particular side of the water that, at this writing, we happen to know that the United States Golf Association has no official knowledge of the action taken, or any intimation that anything of the kind was even contemplated.”

“What is the sense of this country having representation on the Rules of Golf Committee if, as in the case under notice, we are not to be consulted at all in respect to matters of such far-reaching consequences?”

“To be so ignored in this fashion is, to put it mildly, not very complimentary. And it would not be surprising if, in the circumstances, the decision arrived at, which bars all putters of the Schenectady type so commonly used here, were not ratified by the U.S.G.A. We have always been loyal to St. Andrews, even in the face of active internal opposition – which is now happily set to rest – and we hope always to retain the same loyal spirit, but – “It’s all very well to dissemble your love, But why did you kick us down stairs?”

This ruling obviously placed Charles Macdonald in a very uncomfortable position in America. As an advocate for complete worldwide allegiance to the rules of the R&A, the capriciousness and timing seemed at least partially to be politically motivated, and it was difficult to understand (or explain) how banning a popular putter in any way was meant to advance the game in a positive fashion.

Macdonald had tried to walk a very fine line in the matter. During the period when the R&A was considering their position before a final vote that September, he wrote a letter imploring them to exclude the Schenectady as he saw the potential rift it would create, and was aware of the fact that this would be viewed by many as a backlash against Walter Travis. This snippet of the letter he later reproduced in “Scotland’s Gift” gives some indication of his thinking on the issue.

While these contentious events swirled, by July of 1910 Charles Blair Macdonald was finally ready to formally unveil his creation to his Founding and Associate Members. There had been some speculation that this was to be an invitational tournament open to all leading amateurs, but that was not the case as seen in the following two June 1910 New York Sun and New York Times articles.

The following July 3rd, 1910 New York Sun article lists the Founders, including Walter Travis, which should not be surprising as he was still a member in good stead at that time. In fact, pictorial evidence published in American Golfer later that month indicates that Walter Travis played the first day alongside C.B. Macdonald, H.J. Whigham, Fred Herreshoff, and Herbert Harriman.

During the tournament the men played a medal round and then match-play with Walter Travis losing in the finals to Herreshoff, 2-up. That month, Travis reported on the tournament and gave his readers the first glimpses of National Golf Links being played, with numerous photos displayed of the Macdonald, Travis, Whigham group playing together, including a group photo with Travis and Macdonald seated next to each other. Evidently, despite the Schenectady matter things still looked to be personally copasetic between the two men at that time.

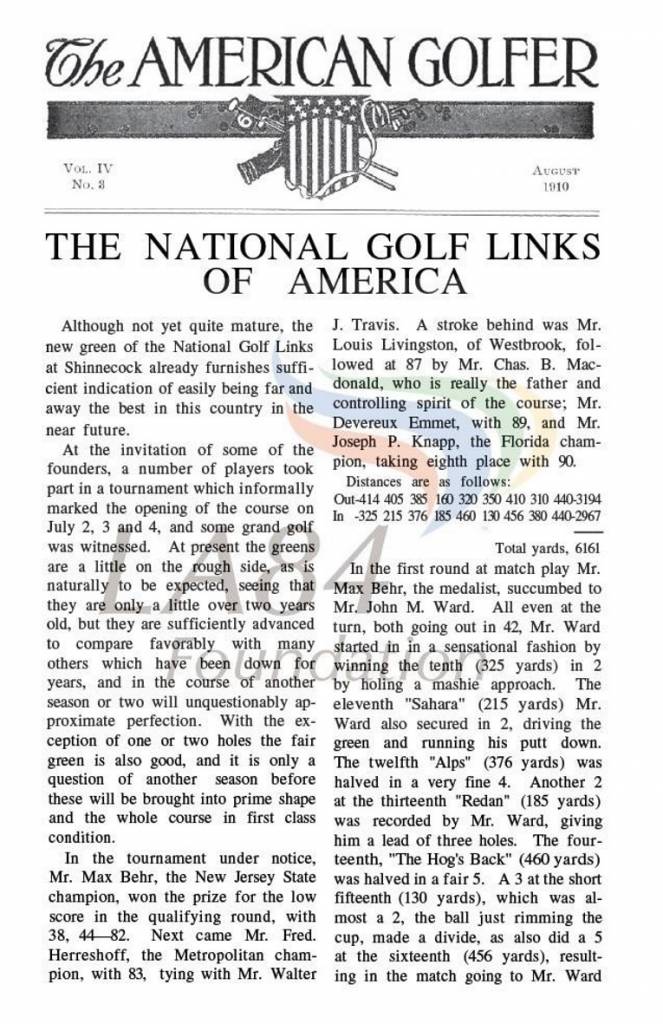

Below is the first page of Walter Travis’ article about the tournament for American Golfer, where with a seeming sense of pride, he claims that the unfinished course still in a rough state would soon be “far and away” the best in this country.

On the last page of the eight-page article, Travis gives primary credit to Macdonald for the creation of the National Golf Links (as well as the reason for that name), and states his opinion that the course is not a slog, despite its eighteen very challenging holes. It’s also seen that Travis is one of the Founders.

In August of 1910 the New York Evening Post mentioned that the course was nearly finished, but again noted that the placement of various traps, etc. would still need more time and study and the expert input of Macdonald’s close friend Horace Hutchinson who would visit for the greater part of a month. It is interesting to note the preferred practice of only bunkering a course after some play was carefully observed, which was the prevailing custom and wisdom of the time. It was also recently determined that a new clubhouse would be built on the Peconic Bay side requiring the nines to be reversed.

In the book “Scotland’s Gift”, published in 1928 a year after the death of Travis, Macdonald mentioned that he “dropped” Travis from the project.

Macdonald’s words may be technically true as the course didn’t officially open until a year later, in September 1911, with another Invitational tournament open to amateur non-members. Up through the fall of 1910 however, it is difficult to view the contemporaneous history and see where Travis was “dropped” from the project.

As documented, all still seemed friendly between Macdonald and Travis through the summer of 1910 and the soft opening tournament at NGLA. There was no indication that Travis was “dropped” from the project and documentation indicates he was there from earlier Founder solicitations in the spring of 1906, through land acquisition, through the laying out and selection of the holes, well into the construction phase through the summer of 1908 and sitting alongside C.B. Macdonald in the group photo at the soft opening in the summer of 1910 after playing together. Travis’ own words about the National course and Charles Blair Macdonald at the time were highly complimentary.

The first hint I can find of trouble creating a rift between Macdonald and Travis occurred later in 1910, a few months after the Members tourney at NGLA and before the official opening of the course in 1911. In September of 1910, the full membership of the R&A ratified the May recommendation of the Rules Committee to ban the Schenectady with little opposition, despite Macdonald’s written appeal. Macdonald was now between an R&A rock and an American hard place as the furor that had started in the spring would now become an inferno.

Travis drew first blood in his November editorial titled, “An Epoch in Putters”, which read in part, “How long does it take for a club to become “traditional”? The Schenectady has been in use for the past ten years, and figured somewhat prominently in the British Amateur Championship in 1904. On this side it is regarded as traditional and is a recognized American institution, and it is not too much to say that exceedingly bad taste was displayed in now banishing it. You may break, you may shatter the vase as you will, But the scent of the roses will cling to it still. We cannot quite lose sight of the fact that in the matter under notice our Association was treated with scant courtesy – our representative on the Rules of Golf Committee not even being consulted on the question until after a premature announcement of guilty had been passed on the Schenectady some months ago. There is no question that the sentiment throughout the country is pronouncedly against the principle just enunciated by St. Andrews. Nine-tenths of our leading players, both amateur and professional, have already expressed dissent from the acceptance of such a ruling …. After all it seems inevitable, and regrettable, that these differences should creep in. In golf, as in other games, the English and the American standpoints are not the same – and never will be the same. The result has found expression in the outgrowth of changes and differences in the rules governing many other common sports and pastimes, but notwithstanding these differences American pre-eminence has not been so far prejudicially affected; nor is our golf likely to suffer.”

It is under that international storm cloud that Horace Hutchinson came to America in September 1910 as the guest of Charles Blair Macdonald. If there was anyone Macdonald saw as a mentor, it was his good friend Hutchinson who was named the first English Captain of the R&A in 1908. As seen in the prior August 1910 article, Macdonald hosted Hutchinson at NGLA and Hutchinson played a few other American courses during his visit. Various articles mentioned that Macdonald was in almost constant contact with Hutchinson seeking advice throughout the several year creation of NGLA, and Hutchinson’s picture is displayed prominently in the NGLA chapter of “Scotland’s Gift“. It was Horace Hutchinson who recommended that Macdonald (as an R&A member) represent America on the Rules Committee.

In November 1910, Hutchinson wrote an article in “Metropolitan Magazine” that effusively praised the National Golf Links of America as basically without fault while essentially trashing all the other courses he played in America including Travis’s beloved Garden City Golf Club. His criticisms didn’t stop there, however, and went so far as to also trash American golfers for practices Hutchinson felt were outside the spirit and intent of the rules of golf.

In the December issue of “American Golfer“, the following scathing reply written by “Americus”, and responded to directly by Travis’ own confirming editorial comments appeared. The editorial soapbox of Travis’ magazine was clearly aggrieved with Hutchinson’s opinions on American golf courses and golfers, something which would not have escaped notice of one Charles Blair Macdonald.

One has to wonder what precipitated such a personalized response from Walter Travis to writings by Horace Hutchinson regarding slights against American golf and golf courses. After he won the 1904 British Amateur Championship, Travis spoke very highly of Hutchinson, reportedly saying; “All things considered, the golfer whom I most admired as a player was Horace Hutchinson. Over here we have read so many of his books and spoken of him so long as a veteran that one is surprised to find he is only fortyseven years old. He plays every shot for what it is worth and in perfect style, as free as any supple youth, and, all told, I pronounce him, to my mind, the ideal golfer.”

It is speculative, of course, but although it was denied, the Schenectady ruling was seen by many as a direct reaction and response to Travis’s 1904 British Amateur win and subsequent March 1910 American Golfer article detailing the events surrounding that tournament. In response to the September R&A decision, Macdonald sent a “circular” to USGA clubs summarizing the proceedings and rationale behind the decision and asked that they acquiesce in the interest of unity behind one set of rules but also suggested a compromise might be possible if the USGA simply interpreted the Schenectady as somehow legal in its interpretation. Such an illogical interpretation of a clear guideline rankled Travis, and although he had been using that type of putter he removed it from his bag in compliance with what he saw as the clear dictate of the R&A. The fact that Travis’ friend Charles Blair Macdonald was on the R&A Rules Committee, and was now seen as publicly defending a ruling he originally opposed probably stung Travis a great deal and possibly felt like a personal affront.

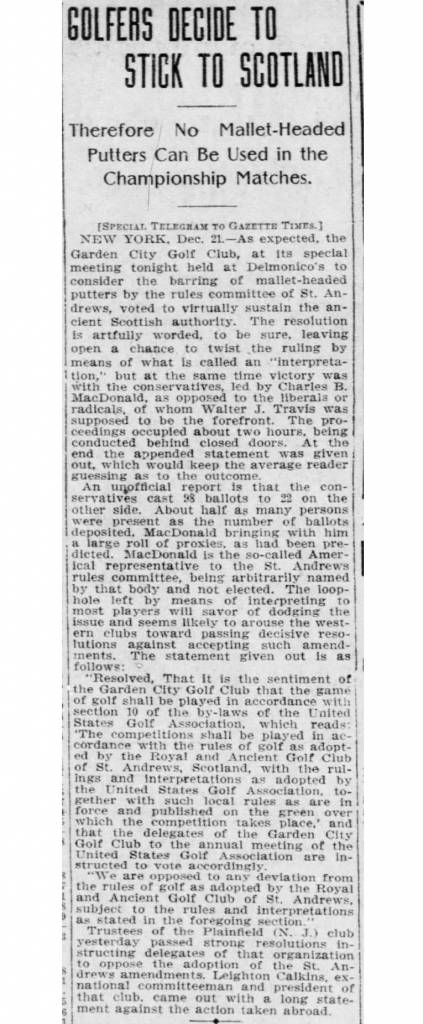

Within the Garden City Golf Club, a meeting was held just before Christmas of that year to vote on the matter. The following day the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette published the following account of the closed door meeting, characterizing the “conservatives” led by Macdonald in victory over the “liberals”, or “radicals” led by Walter Travis.

Those descriptions were somewhat ironic at that stage. It was Travis after all who was taking a very literal interpretation of the R&A’s new ruling, while believing that for the USGA to have integrity it needed to create its own ruling on the matter, not try to hedge or neuter it conveniently for the sake of international relations as Macdonald had recommended. However, whether that was just Travis being intransigent in view of his strained relations over the years with Great Britain, the hard-line approach Travis took put Macdonald in a tough position in his efforts to defuse the issue.

This article by Leighton Calkins of the Plainfield Golf Club was not hyperbolic. The issue had reached a point of boiling over.

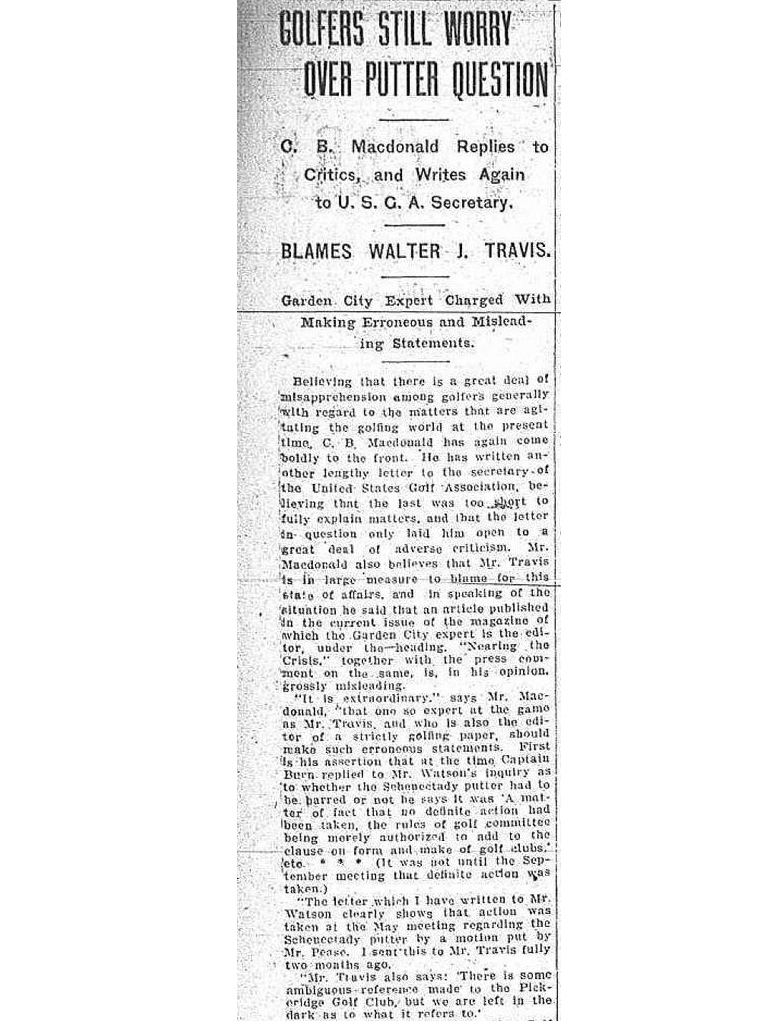

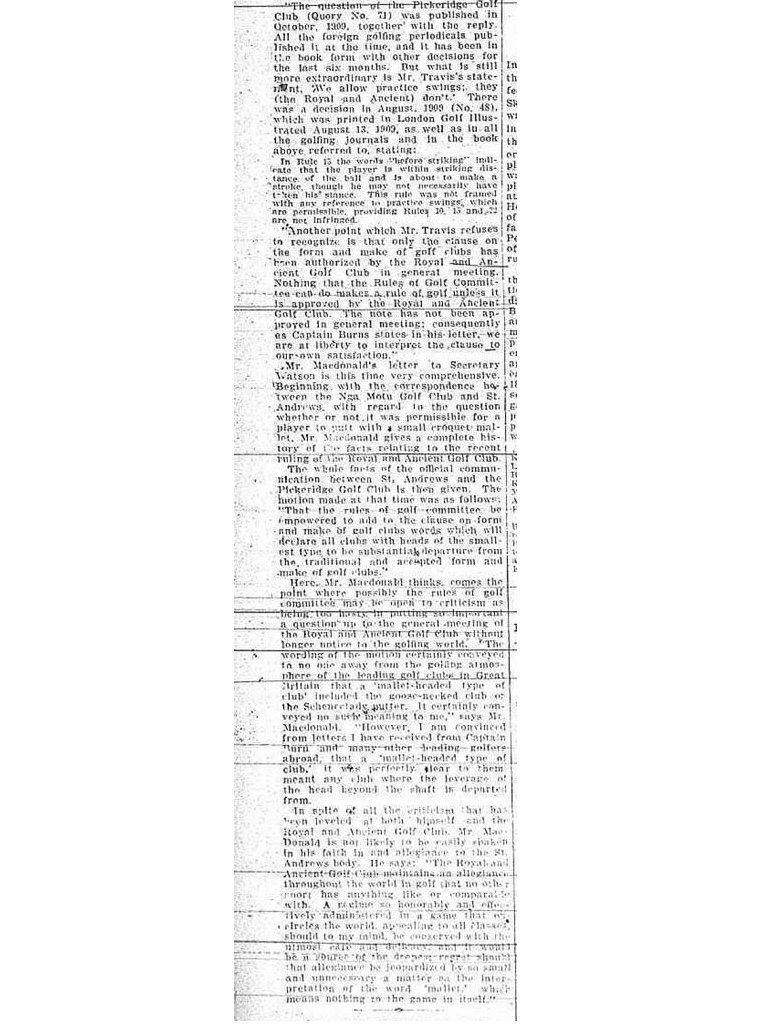

In January 1911, one month after ghost-writing his response to Hutchinson’s golf course criticisms, Travis lashed out against the R&A ruling in an eight page diatribe titled “Nearing the Crisis” that not-so-subtly attacked Macdonald’s role, directly blamed the R&A, involved a US President, and ended up almost calling for a revolution against the R&A in response.

Macdonald, who believed it necessary to the health and future success of the game that all other countries follow the lead of the Royal and Ancient, was aghast and defensive. It is likely that this was the direct cause of the lifelong future division between Macdonald and Travis (and possibly Emmet) after many years of friendship and cooperation that included building the National Golf Links of America. As the course/club didn’t officially open until later in 1911, Macdonald was still technically correct in 1928 when he wrote that “I later dropped Travis.”

Here is the American Golfer article that Travis penned, in entirety, courtesy of the AAFLA website;

Not altogether unsurprisingly, President Taft responded,

THE WHITE HOUSE,

Washington, December 11, 1910.

MY DEAR MR. TRAVIS:

I have yours of December 7th. I think the restriction imposed by St. Andrews is too narrow. I think putting with a Schenectady putter is sportsmanlike and gives no undue advantage.

Sincerely yours,

WM. H. TAFT.

Later in the same issue, Travis continued on the subject, writing; “It has occasioned more or less surprise that within the last couple of months I have renounced the Schenectady putter, using an ordinary putting cleek in the tournaments I have played in since the barring of the Schenectady putter by the Rules of Golf Committee. Perhaps it may not be amiss to explain the precise reason for this change. Some of you may perhaps recall that when the British Amateur championship was brought to this side in 1904, the chief reason adduced by our cousins across the water was that my win was due to the putter I used. That was an easy way of getting out of it; in point of fact the putting was merely incidental, particularly on a course such as Sandwich … However that may be, the fact remains that I used a Schenectady putter … and largely from sentimental reasons I have used one ever since – up till a couple of months ago, since when it has been barred.”

“Right here is where I come in, in a dual capacity.Editorially, I have proclaimed against the principle involved in pronouncing the Schenectady – or any other club – illegal, and have endeavored to show how unnecessary and illogical such an action has been on the part of St. Andrews.Personally, I have submitted to the decree of the ruling body…and have, temporarily, put aside my Schenectady. I say temporarily advisedly, because I am convinced that the good sense of American golfers generally, combined with their appreciation of justice and sportsmanship, will ultimately result in the endorsement of a vital principle in golf – the right of a man to play with any old thing he likes provided it has no mechanical appliances; in short, to play with any kind of recognized club or ball provided the “other fellow” has the same opportunity, or similar choice.”

“Let it be said, in conclusion, and not at all vaingloriously, that the same putting cleek has been just as serviceable as any other kind of putter I have ever used. All the same, I think the Schenectady is the more scientific … and being essentially American I should be profoundly sorry to see it relegated to the dust heap. By all means, let us save it from such ignominy in this country.”

And then, the coup de grace, which considering Charles Blair Macdonald’s allegiance to the Royal & Ancient and his fervent, almost evangelical desire to see a single rules body and single set of rules governing the game wherever it was played may have been the final breaking point.

“It is not at all unlikely that at the annual meeting of the U.S.G.A. a “declaration of independence” will result. The present condition of affairs is extremely unsatisfactory on account of the restrictive and retrogressive legislation recently enacted by St. Andrews. The golfers of America may safely be entrusted with the regulation of the game in this country. Everything points to such a conclusion. And it would not be at all surprising to see such a lead of the U.S.G.A. followed by the inauguration of a French Golf Association, on kindred lines…and, ultimately, the formation of an International Golf Association to define and control conditions governing international competitions pure and simple. In such a melting pot all minor differences would probably disappear and therefrom emerge a universal code of rules…a consummation devoutly to be wished.”

Charles Blair Macdonald barely let the ink settle on Travis’s response before rebutting in kind in a public forum. This article from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle published January 8th, 1911 shows a clearly aggrieved Macdonald firing at Travis with both barrels. He also tries to defend the ruling, and clings to the R&A as being the way, truth, and light of all things golf. Macdonald was not a man to be trifled with; he reportedly wrote a nephew of his out of his will over a perceived golf affront. There is little doubt that he would have done much the same with Travis given that this would have been seen as a direct challenge to Macdonald’s belief in a single authoritarian governing structure (R&A) for the game across the globe including in the United States.

As much as it may have later clouded the history of what actually happened with Travis’s role at NGLA, his insistence that the USGA adhere as much as possible to the R&A may have actually done much to save and promote golf and a single set of rules (with very minor variances) in the United States and worldwide. I think it can be confidently stated that Macdonald essentially straddled the Atlantic Ocean during this time, and played an almost Lincolnian role in preserving the Union, despite the precarious, unpopular position he was placed in by people (including Travis) and events.

Conversely, Travis was an antagonist for some beneficial progressive changes in the game and the rules. His writings spurred some much needed reconsideration and revisions in the rules in everything from equipment to the stymie. He also put himself into the crosshairs of the whole “simon-pure” amateur question as he accepted free golf-related gifts including travel, lent his name to golf equipment for commercial purposes, and designed golf courses. It is not known if he accepted fees for service in that regard before 1916.

In the case of the Schenectady putter ruling, it is clear that Travis felt personally attacked and singled out by the R&A as his reaction over many months seemed to be one of scalded irritation boiling over into defiant rebellion. Charles Macdonald still felt so emotional about the issue years later that he devoted a full seventeen pages to the topic in his 1928 book, “Scotland’s Gift – Golf”. It was clearly the breaking point between the two men, and unfortunately it seems they never reconciled.

Eventually in 1911, the USGA sided with Macdonald’s proposed compromise, to accept the R&A’s ruling in full but creating their own carved-out exceptional interpretation permitting the Schenectady to continue to be utilized in United States competitions.

In September of 1911, the National Golf Links of America officially opened with an Invitational Tournament. It should be noted in the following September 1911 Brooklyn Daily Eagle article that one “W. J. Travis” was not among the 58 participants. It is not known whether he wasn’t invited by Macdonald or whether he refused the invitation.

In October of 1912, Walter Travis’ view of the National Golf Links had evidently soured. He wrote the following in “American Golfer” under the heading “TOO SEVERE”; “There is no question that they have overdone it at the National course. It is too severe. We refer, of course, to the course of the National Golf Links of America at Shinnecock Hills, sometimes known as the “ideal course. The primary idea was to make each and every hole an exacting test; to copy, so far as Nature would permit, certain of the famous holes abroad, and to make the whole eighteen “ideal” holes. So far as reproduction of any of their prototypes is concerned – whether it be the “Sahara” at Sandwich (of which the second at the National is supposed to be a copy), the “Alps” at Prestwick (represented by the third), the “Redan” at North Berwick (the fourth) or any of the others – without going into elaborate description – the simple fact remains that outside of the general principles, in a broad sort of way, none of the physical features of any of these holes has been reproduced. The whole face of Nature would have to be radically changed, at incalculable expense, to permit this – and even then they would not be alike. For the simple reason that it would be impossible to duplicate the soil, the turf, and the general environment. The plain truth is that they have overdone it at the National. The scores in the recent tournament go largely to support this. Fancy Mr. Norman Hunter taking 87 at St. Andrews or Mr. Hilton 89! as they did at the National. They have overdone it in making every hole a very difficult one. It is too much. There is no letup – no breathing spell; one’s nose is everlastingly at the grindstone. Which, after all, is not golf. For golf is a game – a recreation. Take any of the championship courses on the other side and what do we find? Four, five or six holes of the eighteen very severe; the rest, interspersed, of the usual type to be found on good courses. Good holes, but not all of the “death or glory” type. That would be asking too much, even at the hands of the most finished exponents of the game.”

It is worth considering that over two years had passed since Travis played in the original Founders Invitational tournament and perhaps Travis legitimately believed that all of the bunkering that had been created on the course since that time with the guidance of Horace Hutchinson was overdone or created too much of a burden for the average player.However, the irony of the man who added scores of deep bunkers to Garden City now criticizing much the same at National Golf Links was not overlooked by the New York press, as this “Brooklyn Daily Eagle” article portrays;

Ten days later an official rebuttal was printed in the same paper by “members” of the club.

It is not known if the Travis criticism preceded or followed the publication that same year by Charles Blair Macdonald of a 25-page treatise sent to his (at that time) one-hundred Founders titled “National Golf Links of America”, the club of which Walter J. Travis was no longer a member.

Travis had now completely disappeared from the National Golf Links scene despite his obvious and welldocumented involvement in the project from 1906 through at minimum 1907 and almost certainly 1908 and possibly beyond until their falling out around the Hutchinson criticisms, the Schenectady Putter dispute and CBM’s offense at Travis’s suggestion that the USGA should break from the R&A.

It is interesting that CBM somewhat couched his remarks by making them specifically about those Founders who helped with the project, yet later he credits others without a mention of Walter Travis, who was evidently a non-entity to Macdonald by that time.

CBM wrote;

Co-operation of Founders

In the accomplishment of this work I have had cause to call upon the following Founders in their various capacities, and we are much indebted to them for their assistance: For aid in the original purchase of the land and in the laying out of the course we must thank Mr. H. J. Whigham and Mr. Devereux Emmet. Since then Mr. James A. Stillman and Mr. Joseph P. Knapp have been most deeply interested in the development of the course, and have expended much time and energy in helping to bring it to perfection…We have also been helped by some of the most eminent men in the game of golf abroad, who have taken a most friendly interest in the undertaking, and I have to thank among these Mr. Horace G. Hutchinson, Mr. John L. Low, Mr. Harold Hilton, Mr. J. Sutherland, Mr. W. T. Linskill, the Messrs. Walter and Charles Whigham, Mr. Patrick Murray, Mr. Alexander MacFee, and the late Mr. C. H. Everard, for the maps, photographs, and suggestions which they have given us.

Finally, he also mentions those outside the organization, but again no mention of Walter Travis.

It is but proper, too, that I should say a word of thanks to those outside of our organization who have aided the undertaking. I cannot speak too strongly of the work of Mr. Seth J. Raynor, civil engineer and surveyor, of Southampton. In the purchase of our property, in surveying the same, in his influence with the community on our behalf, and in every respect, his services have been of inestimable value, and I trust that the club will extend to him the courtesies of the clubhouse during his lifetime.

It is pretty clear that one did not cross Charles Blair Macdonald without permanent consequences!

Perhaps later realizing he was being completely and permanently written out of the NGLA creation story, Travis inserted this blurb titled “FACTS FOR POSTERITY” into the November 1914 American Golfer ;

In March of 1915 Travis wrote a more extensive criticism in “American Golfer”, perhaps now recognizing that reconciliation with Macdonald was impossible.

In 1916, after years of discussion, the USGA finally ruled on toughening their amateur criteria, a ruling that also affected any architects who accepted pay for their work including Walter Travis. The somewhat broad, draconian ruling also affected Francis Ouimet whose work for a sporting goods concern prior to his 1913 U.S. Open victory now swept him into the “professional” net. Although this article seems to indicate otherwise, I’ve found no other evidence that Travis was forced to relinquish his Garden City Golf Club membership due to his becoming a professional architect.

Finally, it seems the falling out was not only between Macdonald and Travis but there was possibly some collateral damage with Travis’ old friend Devereux Emmet. It is also believed that this fracture was later significantly exacerbated when Emmet undid some of Travis’ changes at Garden City during the teens and Travis responded with very public criticism to those actions. A few years after World War I, Emmet tried to make peace with the following letter to Travis. It is not known if Travis ever responded;

In summary, there is no question that Charles Blair Macdonald was the primary force, chief driver, and ultimately the creator of the National Golf Links of America. However, like most of those early amateur efforts, it was a multi-year process involving collaboration of multiple individuals and most often there was a “committee” charged with the work of designing the course and overseeing its construction on the ground. This was also the case with the National, and it seems very clear from the contemporaneous evidence that Walter Travis played a significant role in that effort as a member of Macdonald’s committee through much of the design phase of the project. It also seems clear that once the two men had a falling out over the issues outlined within this document that Travis was expunged from the club and the history of the club.

A deconstruction of the architecture of the National Golf Links of America to find evidence of Travis’ input is ultimately an unsatisfying, somewhat pointless exercise. Certainly one can point to greens like the rollicking 1st hole or the long, au naturel expanse of the 10th as very similar to some of Travis’ best, or the converse bunkers … literally upturned mounds of sand on the 9th and 17th as a common Travis feature, or the planting of bushy grasses in the sandy areas that Travis often employed for visual texture and whimsical challenge, or the creation of indirect, safe avenues of play for the shorter hitter evidenced throughout, but ultimately one must remember that both Macdonald and Emmet would have been very familiar with those same features that Travis added to Garden City Golf Club, so it becomes a unsolvable case of whose chicken laid what egg.

What we do know for certain is that Walter Travis went on to become a very successful architect responsible for a number of wonderful courses from Georgia to Canada (primarily in the Northeast) and what impresses most observers in modern times are his bold, multi-faceted green designs that offer seeming infinite variety of internal contour. Travis’ bunkering was also distinctly varied, and the fortunate visitor who gets to see their placement, shaping, and audacious nature at courses like Hollywood, or Garden City, or Scranton receives a silent Masters-level tutorial in the art of requiring tactical shot placement and strategic decision-making.

Unfortunately, his health started failing him in 1911 and most of the last fifteen years were spent battling various respiratory and assorted other maladies. His last courses, Equinox in Vermont built next door to his beloved Ekwanok and the Country Club of Troy in upstate New York could only be viewed by Travis as he was driven around, his respiratory system was so incapacitated. He died that summer of 1927 in Denver (where it was hoped the less humid air would help him convalesce) and he was buried in Manchester, Vermont near his cherished Ekwanok in accordance with his wishes.

While Travis’ architectural career after turning professional in 1917 has previously been well documented, I don’t believe that his work to help bring strategic golf course architecture to America has ever been well understood or formally acknowledged with the type of chronological context that has been attempted in this series of articles. I believe it is fair to say that Travis was a golf “scientist”, a term with which I believe he would agree with, appreciate, and enjoy. This description extended from his self-taught, trial-and-error approach to learning the game, to his near constant tinkering with equipment, to his deliberate, sternly quiet demeanor during every round of golf, competitive or friendly, and to his careful study, documentation and subsequent application of what constituted interesting and challenging strategic golf course architecture.

To consider his early progression from designing courses just a scant few years after beginning the game with professionals like Thomas Bendelow and John Duncan Dunn, to the great revelation and profound enlightenment he experienced seeing the sterling courses of Great Britain in 1901, to his employment of those principles at his home club of Garden City, to his literal campaigning and near constant writing about the philosophies and practicalities of sound, challenging, inspiring course design, to his considerable influence on his friends like Donald Ross, and yes, his Garden City (and National Golf Links) club-mates Charles Blair Macdonald and Devereux Emmet he might well be considered the father of strategic golf theory and application in America.

Walter James Travis, golf scientist extraordinaire, we hardly knew you.

Mike Cirba

May, 2018

Acknowledgements: The author wishes to gratefully acknowledge and thank the following people and sources who contributed to the content and review of this series of articles. The furthering of historical research is always dependent on one’s standing on the shoulders of those who performed previous related work and the “hunting and gathering” process of synthesizing prior published works from multiple sources sometimes yields new insights and perspectives. I’m hopeful that’s been the case with this series of articles.

In particular, I’d be remiss not to specifically call out in gratitude the following sources as foundational to this effort. First, my close friend Joe Bausch has unearthed a wealth of contemporaneous historical golf course information from old newspaper articles, some of which inspired these essays and a good number of which appear herein. The late golf-writer Bob Labbance’s book “The Old Man – The Biography of Walter James Travis” was incredibly valuable as source material for understanding the life and times of Walter Travis, particularly his early, formative years. And special thanks to Ed Homsey, the Historian/Archivist of the “Walter Travis Society”, who kept me honest, enthused and on point throughout the process and helped correct and refine my understanding of all things Travis. This work would not have been possible without them.

Jim Kennedy

Shawn Harrington

Tom Paul

Matt Frey

John Burnes

John Yerger

Geoff Walsh

Tommy Naccarato

Anthony Pioppi

Bob Crosby

Sven Nilsen

Tom MacWood (deceased)

“Scotland’s Gift – Golf – Charles B. Macdonald

“Centennial History of Ekwanok Golf Club” – Sydney N. Stokes

“History of Essex County Club 1893-1993” – George C. Caner

“The Evangelist of Golf – The Story of Charles Blair Macdonald” – George Bahto

“America’s Linksland – A Century of Long Island Golf” – Dr. William Quirin

“Golf Clubs of the MGA” – Dr. William Quirin

Manchester (VT) Historical Society

The Walter Travis Society Website travissociety.org