Walter J. Travis “Dropped” at National Golf Links of America

Truth or Travesty? (Part One)

by

Mike Cirba

April 2018

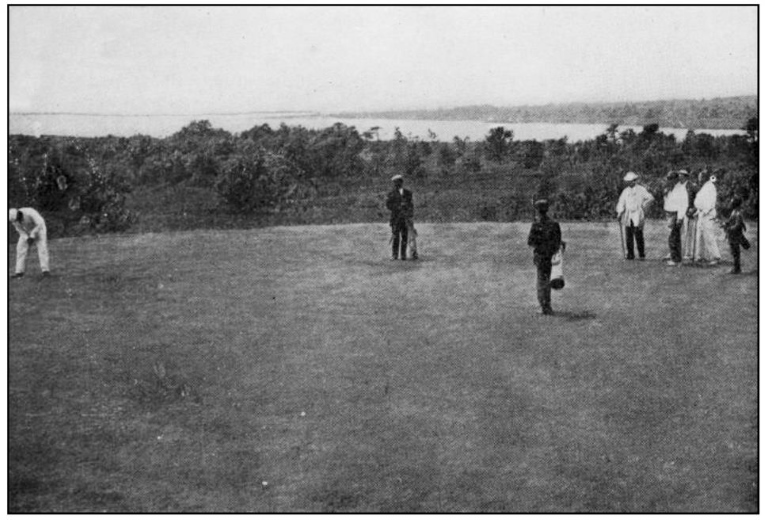

July 1910 “Soft Opening” Invitational Tournament for Founders and Members – National Golf Links of America (Left to Right) Charles B. Macdonald (putting), Walter J. Travis, Fred Herreshoff, H.J. Whigham, and Herbert Harriman.

As an émigré to the United States in the 1800s, he was the closest thing to a golfing savant in the history of the game. In less than a year after picking up golf clubs in the fall of 1896 he was winning competitive events and soon became one of the premier amateur golfers in the country. In the earliest, formative years of the game here in the states he was a stalwart on the Rules of the game, staunch defender of its integrity, and a quick student on everything from agronomy and course construction to proper swing technique.

By the late 1890s he was designing new golf courses and in the earliest years of the 20th century he went abroad to study the classic courses of Great Britain, a trip which could be rightly described as transformative to his thinking. His writings about the game helped to change the American mindset of what constituted a great golf course and he railed against the rote, crude, cross-bunkered steeplechase golf that constituted most courses in the country at this time. His outspoken writing in several publications helped to launch an understanding of the constituents of strategic golf, and he advised and chastised a number of prominent Scottish professionals in this country to design courses here more congruent to the standards of the great courses of their homelands.

His proposed redesign of his home golf club was extraordinary and controversial in nature, yet is still acclaimed to this day as being wonderfully creative and exemplary of how to introduce challenging variety on a flattish site. On the competitive stage, by 1904 he had won the United States Amateur title three of the previous four years and in 1904 stunningly won the British Amateur, the first American to win that vaunted trophy and a unique accomplishment that would stand for over two more decades.

So when it was determined in 1906 to build an “Ideal Golf Links” in this country, one based on the best qualities of the classic courses abroad, there was no one in this country with more architectural knowledge, competitive accomplishment, and passion for the game for Charles Blair Macdonald to reach out to for assistance than his good friend and club-mate Walter John Travis.

Both men shared strong personalities with intense personal drive and ambition bordering on a sense of entitled predestination. Although their golf-related endeavors shared many remarkable parallels, fundamentally the two men came at the game with much different backgrounds and perspectives. Macdonald, coming from a long family lineage of privileged wealthy landowners had been sent to St. Andrews, Scotland to study shortly after the Chicago Fire in 1872 at the age of 16. There, he quickly became enamored of the spirit of the town and fell in love with the ancient game of golf under the wise tutelage of Old Tom Morris while attending St. Andrews University. Embracing his newfound romantic interest with the fervor of a man possessed, Macdonald was soon playing competitively against the best Scottish players, including Old Tom’s son, “Young Tommy” Morris, Jr.

At the time, Walter Travis was nine years old and still living in Australia, the fourth of what would be eleven children (seven boys and four girls, although four would die before their tenth birthday) born to Charles and Susan Travis, the family making a living through Charles’ employment in various capacities in the gold mining industry in the burgeoning town of Maldon. Young Walter was bright and energetic, but although he played competitive sports (i.e. cricket, tennis) in his teens he did not achieve much success. What he did realize quickly was a love of the outdoors that manifested itself in young Walter leaving jobs in hardware and grocery stores to become a sheepherder during his teens.

A year later tragedy struck the family when Charles Travis was killed in a mine explosion. A year later Walter lost his only surviving older brother and took on the de facto “father” role to the remaining family and soon moved to the city of Melbourne to take a job with McLean Brothers, a growing hardware and ironmongery merchant. Ambitious Walter rather quickly caught on and sent money back home to his mother and six children in Maldon. When the company opened a New York office in 1885 and a year later asked eager 24 year old Walter if he’d be interested in helping to get it established. To golf’s great future gain, Travis accepted the job and moved to New York in 1896.

At that time, Charles Blair Macdonald was in his twelfth year of what for him must have felt like banishment to the desert, his so called “Dark Ages”. Having had a glorious two year exposure to the game of golf at St. Andrews, he returned to the golf-barren Chicago where he put his nose to the grindstone and became a successful stockbroker. He fed his soul with intermittent trips abroad where he would once again immerse himself into the deep waters of golf; only to come home to what in contrast seemed a joyless existence.

By the mid 1880’s Americans began to experiment with the novel, if ancient game in remote places like Foxburg, PA and Dorset, VT, but it wasn’t until 1888 that golf became established just outside New York City and garnered wider exposure with the formation of the St. Andrews Golf Club of Yonkers, NY.

Macdonald was one of the first to sense the opportunity. By 1892 he convinced several of his associates and friends to try the game and laid out the first rudimentary nine holes of the Chicago Golf Club, the first such entity west of the Allegheny Mountains. A year later the course was expanded to what was becoming the new “standard” number of 18 holes after its adoption in St. Andrews a few decades prior. Macdonald must have felt like a man released from the wilderness, and his strong sense of purpose included strict adoption in America of and allegiance to the rules as laid down by golf’s Vatican City, the Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St. Andrews, Scotland. To Macdonald, golf was a simple game needing few rules but those that existed from the motherland were Holy Writ. It was a position he would defend through much of his life.

In the intervening decade, golf caught on and grew quickly in and around Chicago and New York City, as well as Boston and Philadelphia. In 1894 Macdonald was instrumental in the formation of the United States Golf Association which started with five charter clubs (i.e. St. Andrews, Newport, Shinnecock Hills, Chicago, and The Country Club) and was elected its Vice-President. A year later Macdonald used his greater experience in the game to win the first of the organization’s Amateur Championships by a match-play margin that still stands as a record today.

While Macdonald was busy advancing his life’s love, Walter Travis viewed its growth from his offices in New York City (and London) with a sense of marked disinterest. “I was in London in 1895-1896 and learned that the Niantic Club, a social organization in Flushing, Long Island intended starting a golf club…but the game made no appeal to me. I am free to confess that I had mild contempt for it, inspired possibly by the garb of the players…” he later wrote in American Golfer.

At the time, Travis had taken to big city life with a flourish. During those intervening years, Walter had met and wooed a wife Anne Bent in 1890 and after a short time in a boarding house in New York City they saved enough money to move to a small home in Flushing where they had a daughter and son under their roof. Despite these trappings of domestication, Walter continued to refine his affinity for cigars and whiskey. He also still pursued his hunting and tennis and passionately joined the bicycling craze that was sweeping the nation, often racing madly through the city streets to and from work, his skinny legs pumping furiously with determination. Travis’ drive and ambition was noticed within the company and he soon had responsibilities in both New York and London.

In fact, by this time Travis had begun to view America as the land of opportunity and despite his Australian upbringing began to see himself as a proud and independent American, soon becoming a naturalized citizen the year he was married in 1890. In contrast, it is arguable that Charles Blair Macdonald’s heart and homage remained in the beloved Scotland of his formative years.

The fates sometimes conspire in mysterious ways, leading to sometimes historic seismic cultural shifts. Whatever the odds of four musical lads later meeting in the seaport of Liverpool, or a young Francis Ouimet growing up right across the street from The Country Club, by the year 1900 the gods of golf determined to take these two ambitious men of vastly different backgrounds and upbringings and put them in the same city, and even the same golf club. There they would become the first two titans of the game in this country and together and separately they changed the game of golf and trajectory of golf course architecture forever.

It is argued that often great relationships start with a bit of disdainful aversion, and it was likely with some fatalistic reluctance that Travis purchased a set of clubs before leaving London during the second part of 1896 and sailed home with them to America that fall.

He later wrote, “However, I realized that I would have to sink my prejudices and start in with the rest of the Niantic boys so I equipped myself with a set of clubs and, with anything but pride, brought them over on my return. In the early part of 1896 the Oakland Golf Club of Bayside, L.I. was formed and in October I first knelt at the shrine of the Goddess of Golf…and ever since have been a devout worshipper of the Royal and Ancient game.”

If there was ever such a thing as a golf prodigy, then thirty-five year old Walter Travis was one. John H. Taylor had hired Tom Bendelow to stake out a nine hole course for his budding Oakland Golf Club earlier in 1896 and it was there that Travis first took to the game with the religious fervor of a zealot.

Near constant play, practice, and careful study quickly followed Travis’ inaugural foray, and within a month after touching his first golf club Travis won first prize in the club’s first handicap tournament with the best gross score. By the end of the year Travis also held the course record of 42 shots for nine holes.

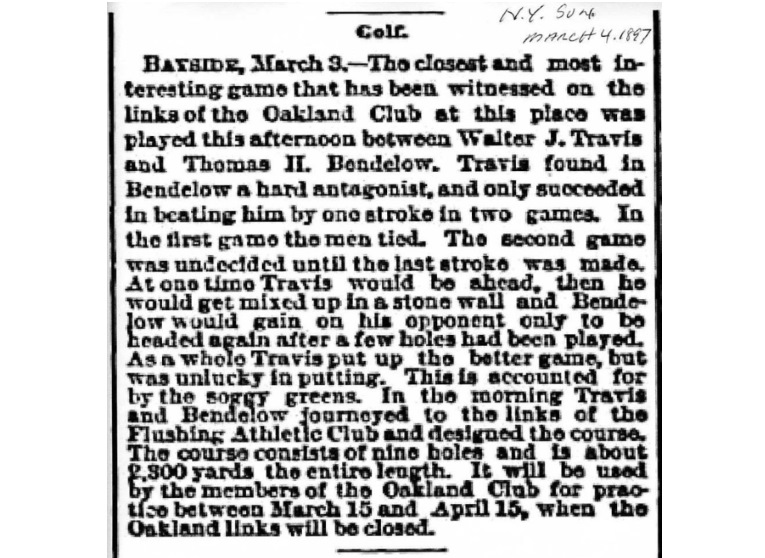

The rolling undulations of the Oakland course proved to be an excellent training ground for Travis to develop his game. Already the best player in the new club, by early 1897 the nearby Flushing Athletic Club which shared many members with Oakland determined to build a short course nearer to town that could be used by women and by members during the shoulder season. It was also apparently Walter Travis’ first venture into golf course architecture, working alongside Thomas Bendelow.

By today’s standards, it was hardly an auspicious debut, but does reflect the state of architectural thinking at the time. This April 11, 1897 Brooklyn Daily Eagle article describes the individual holes with fences and cornfields and roadways providing most of the hazards.

Through the rest of 1897 and first part of 1898 Travis expanded his reach, competing in and winning various tournaments in and around the New York City region and by September 1898, less than 2 years after picking up a club, Travis entered into the United States Amateur tournament, held at Morris County Golf Club, in New Jersey.

During those same years Charles Macdonald continued as an active national competitor and both he and Travis made it to the Semi-Finals at Morris County before losing. But Macdonald was also greatly concerned with ensuring that the rapidly expanding game in the United States maintain parochial lockstep consistency with the rules as defined by the Royal and Ancient Golf Club in St. Andrews.

In 1896, Macdonald and Laurence Curtis of Brookline were appointed to a special USGA committee to “interpret the rules of golf and to present their report for action at the annual meeting.” Looking to his old friend Horace Hutchinson for guidance, and assistance from the R&A in settling a number of rule disagreements in the states. Hutchinson wrote in 1897, “It is not the purpose of this article, however, to put forward my own or any other individual opinion, but simply to bring to the notice of golfers the desire of golfers in the States for a community of golfing opinion and a uniformity of golfing rule.”

When the Macdonald/Curtis report was finalized later that year, they were heartened that, as Macdonald later wrote, “The five charter clubs were unanimous on one point, and that was we should play the game of golf as it was played in Scotland, as evidenced by the rules adopted by the Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St. Andrews.”

Soon thereafter the USGA was also wrestling with the question of what constituted a true “amateur” and modifications to the original definition in the 1895, by-laws were enacted in 1898 and again in 1899 and 1901 to very narrow terms. In essence, a “professional” was defined as any person “Who receives a money consideration, either directly or indirectly, by reason of his connection with, or skill displayed in playing the game of golf; who is classified as a professional in any athletic sport; who sells or pledges any prize or token obtained through connection with the game of golf; who with the intention of promoting any business, receives transportation or board, or any reduction or equivalent thereof, as a consideration of his playing golf or exhibiting his skill as a player; who has club dues or charges paid by another person, as an inducement to become a member of a club.”

While such stringent definitions may have been easily financially attainable by many of the inherently wealthy bluebloods who made up he early American game, to a climbing businessperson like Walter Travis in his mid-30s with multiple responsibilities and a wife and two young children to support it was not nearly as clear cut on how best to fund his competitive golf travels. This issue would continue to dog Travis throughout much of his playing career.

In 1899, largely due to Macdonald’s influence, the Ontwentsia Club in Chicago was awarded the most prestigious competitive event, the United States Amateur tournament. At first, Travis and some other eastern players refused to go to Chicago for the event, only to subsequently change his mind. Once again, both Travis and Macdonald made it to the semi-finals before losing, Travis both times to Findlay Douglas.

While this matter of where to host the event was settled amicably, it was the first of several very public flare-ups where the upstart agitator Travis would challenge the very structure and decision-making of the fledging United States Golf Association, and by connection, it’s most ardent official, Charles Blair Macdonald.

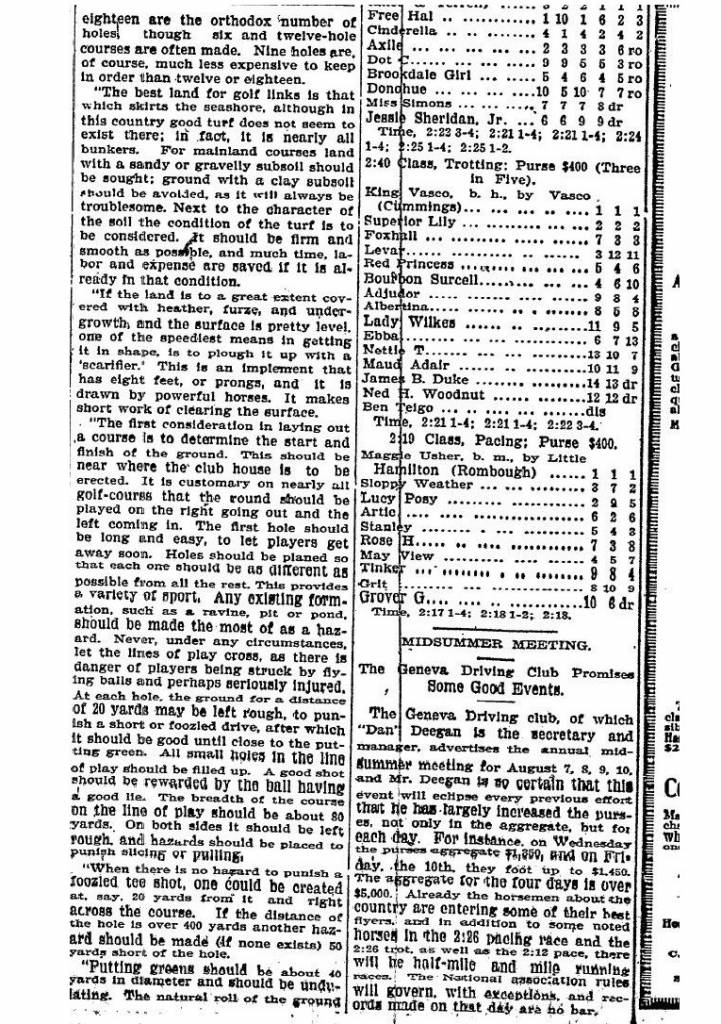

1899 also marked the year when Walter J. Travis became deeply involved with golf course architecture. His close friend and Dyker Meadow club-mate James F. Taylor was also a member of the Equinox Club in Manchester, Vermont and Taylor asked Travis to come up and see if a large property he was considering buying might be attractive for golf. Taylor, the son of a wealthy Brooklyn industrialist learned the game with his father during visits to Scotland and he became one of the early adopters of the game in America. Taylor possibly believed that Travis’s dazzling, virtuoso golf skills and persistent personal drive might instinctively translate into knowledge of how to design and develop a great golf course. Probably uncertain of himself, Travis asked Ardsley Casino professional John Duncan Dunn to accompany him. Dunn, the son of famous Scottish golf architect Tom Dunn had arrived in America in 1896, and took the professional job at Ardsley Casino where his uncle Willie Dunn had designed the golf course and then employing an arduous and creative construction process, eventually carved out eighteen holes on a hilly, rocky, forested site. Soon after his arrival, young Duncan Dunn was being asked to design courses of his own and modify existing ones, often in a day or two’s site visit as was the custom of the time. Dunn had previously designed a few of the earliest rudimentary courses in the Netherlands. By the year 1899, he had developed a reputation as a consummate golf professional. His early ideas on golf course architecture were reported in this Elmira (NY) Daily Gazette article published in July 1900.

The land for Ekwanok was purchased by Taylor in late August 1899 and in September the club was formed. With an aggressively planned course completion date of June 1, 1900, design and construction work commenced almost immediately and 42 workmen were employed until November 23rd, when work had to be abandoned until spring. By June 7th, 1900, 12 of the holes were completed and it is believed the others opened by mid-August, when a small Invitational gathering took place.

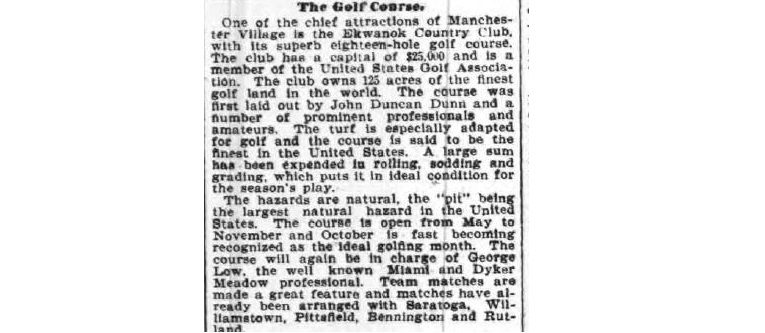

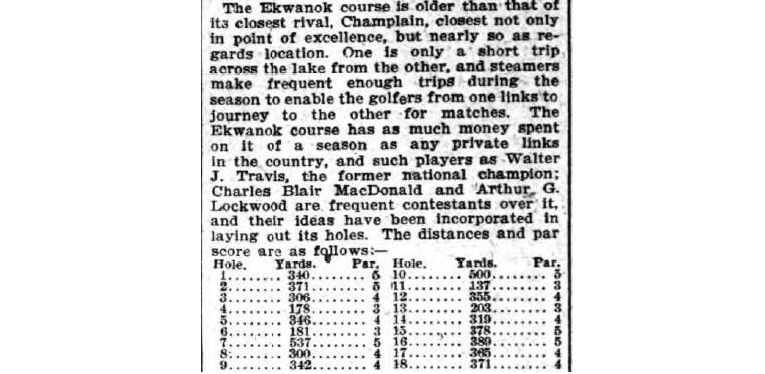

The understanding within the club is that Dunn and Travis jointly laid out the course and Dunn returned to New York but Travis visited regularly during construction to oversee matters in the fall of 1899 and spring of 1900. Dunn did return to Ekwanok in July 1900 to review progress and stayed on to play in some of the early club events. While most of the early news reports mentioned John Duncan Dunn’s direct involvement, it also seems clear that the early Ekwanok course in its first formative years was a collaborative design work, with some of the best minds in golf weighing into the final product with Walter Travis being the predominant force mentioned but over time, others like professional George Low and amateurs Charles B. Macdonald and Arthur Lockwood also advising. This from a May 1901 Troy (NY) Daily Times article:

By July 1903, this snipped from a New York Herald article expanded the listing of prominent golfers whose ideas were adopted into the course design.

On July 2nd, 1900, several days before the course opening and a week before Walter Travis won the first of his U.S. Amateur Championships, the Ekwanok Board of Governors made him its first Honorary Member. Four years later, after winning the 1904 British Amateur, then club President Robert Todd Lincoln (son of Abraham Lincoln) sent the following congratulatory note to Travis (via Garden City Golf Club) that provides the likely reason he was granted such a distinctive honor.

“The Ekwanok Country Club in annual meeting assembled sends greeting to the Garden City Golf Club upon the occasion of the complimentary dinner given to Mr. Walter J. Travis, to whom it is most indebted for the laying out and development of its course (bold emphasis by author) and who was its first Honorary Member and requests the President of the Garden City Golf Club to present to Mr. Travis the congratulations of the members of the Ekwanok Country Club upon the great victory achieved by him in winning the Amateur Golf Championship at Sandwich”.

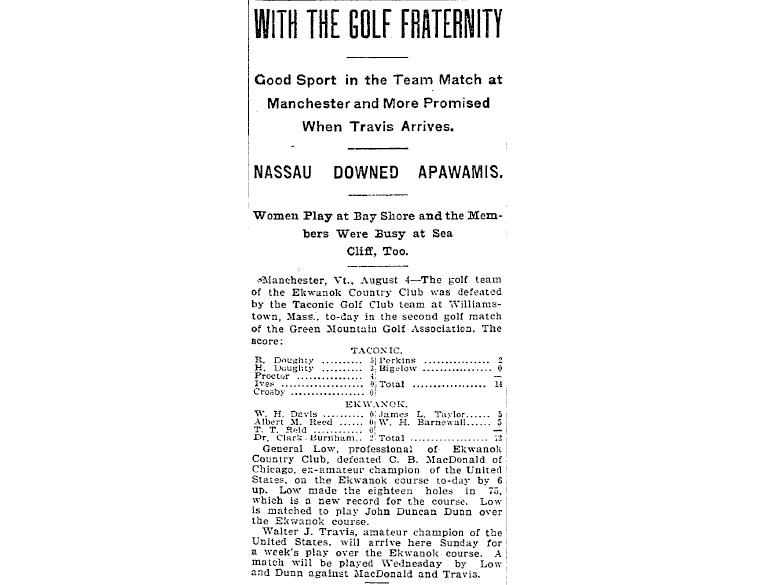

In August of 1900, the club hosted a series of exhibition matches that pitted some of the top professionals and amateurs, including one where Walter Travis and Charles Macdonald teamed up against George Low (who had become Ekwanok’s new pro earlier that year) and Willie Davis, the professional at Shinnecock Hills. John Duncan Dunn who had returned with his new wife, an heiress of the Wilshire family of Los Angeles participated, as well.

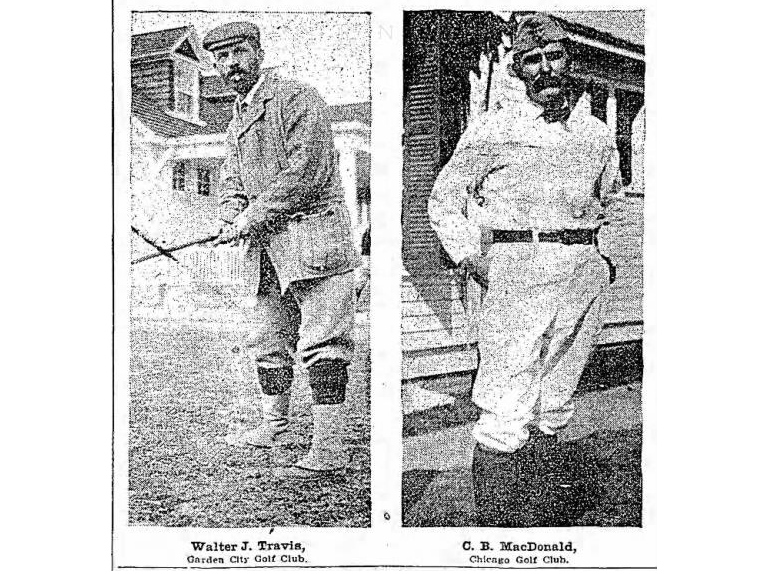

Charles B. Macdonald driving at the 18th hole of the newly opened Ekwanok while Walter Travis looks on in foreground on August 14, 1900.

Interestingly, even though Travis did not become an “Honorary Member” until July 2, 1900, he already appeared on the club’s membership roster a month prior as the Troy (NY) Daily Times article from June 11, 1900 indicates.

Whatever the architectural relationship between Travis and Dunn, it was a friendship and working association that would continue intermittently over the next two decades. In the case of Ekwanok, they created a course that was immediately recognized as one of the premier courses in early American golf, and along with Myopia Hunt, Garden City, and Chicago Golf, was considered one of the most architecturally sound courses built in the United States prior to the opening of National Golf Links in 1910/11.

The year 1900 would be an eventful one in New York City. That year Charles Blair Macdonald left Chicago and moved to New York, that year becoming a member of Garden City Golf Club along with Walter Travis. From a competitive golf perspective, Macdonald’s career was slowly descending while Travis was nearing his peak. Although Macdonald was just shy of seven years older than Travis, it is important to consider that Macdonald was already 45 by this time.

At the prestigious Atlantic City event in the spring, Travis perhaps foreshadowed what was to come by defeating his nemesis Findlay Douglas and again at the US Amateur in July at his home course of Garden City Travis defeated Douglas 2-up on the 18th green in dramatic fashion in a violent rainstorm. Macdonald didn’t play that year, returning early to Chicago at the time to help arrange for a visit by Harry Vardon, as well as watch the United States Open at Chicago Golf Club which Vardon won.

At native Garden City, Travis’s short game proved magical, as evidenced by his recovery from very near the road on the 9th hole for a halve. “It was the greatest shot I ever saw”, said Devereux Emmet, who was following the match and had just returned from a tour of Scottish Links. Travis had quickly reached his most important goal and in terms of his limited playing experience, was venerated in the New York press as an overnight success.

During this same period it is believed by some that Travis and John Duncan Dunn (with assistance from Herbert Leeds of Myopia) were also responsible for the modification of the existing nine holes and the addition of nine new holes at Essex County Club in Manchester, MA. The construction of the new holes took place on hilly, wooded, rocky terrain that required dynamite blasting and various other extreme techniques previously employed by Willie Dunn at Ardsley Casino. Essex County’s first eighteen hole course (Donald Ross significantly changed it during his tenure there during the teens) was started in 1899 and opened in September 1900 with an exhibition featuring Harry Vardon, and then a week later John H. Taylor, so it was a course and club of some repute. Cornish & Whitten’s books list Essex County’s first eighteen hole course as attributable to Dunn and Travis (NLE), and today both Golf Digest and Massachusetts Golf Association information note the same attribution. Unfortunately, the author has been unable to find contemporaneous evidence to bolster that contention, and somewhat oddly, the 1993 Essex County Centennial History book by George C. Caner, Jr. includes this perplexing, unexplained notation;

“The architect is not recorded, but Herbert Leeds, creator of the Myopia course, John Duncan Dunn, and Walter J. Travis may all have been involved.”*

*The author welcomes any supporting or refuting sources from the club and/or interested parties and will ensure that this article is revised accordingly.

What is known for certain is that Walter Travis did make significant revisions to the Essex County course during a 1908 visit (including three completely new holes) during which he won an invitational event there. Most of his suggestions included significant widening of holes, removal of cross bunkers, and the addition of hazards that were more along the outside lines of play.

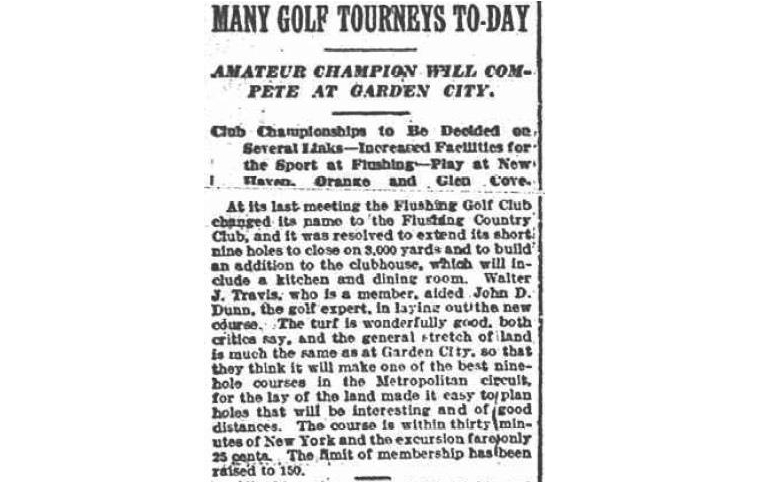

Travis and Dunn collaborated again in 1901 by fashioning a brand new nine hole golf course for the Flushing Golf Club (formerly known as Flushing Athletic Club), where Travis was also a member. Please note that this was the same club where Travis and Thomas Bendelow first laid out a modest, rough-hewn 2,300 yard nine-hole course in the spring of 1897. The new course was a whopping (for the time) 3,000 yards and the club and golf course prospered until the late teens when the course was deemed too confining due to popular growth and some members purchased nearby land for a new Devereux Emmet course in 1920. Some loyal members remained at the original course, however, expanding it to 18 holes in 1924 and it became known as the “Old Country Club”. The club did not survive the Great Depression, closing in 1936.

Earlier in 1901, Travis went on two golf vacations, both of which would have a decided impact on his development and understanding of his place in the game. The first, a winter trip south to Florida described below would soon turn into an unexpected brouhaha as Travis’s amateur standing was challenged.

The fact that the USGA’s definition for amateur violations was drawn so broadly (as mentioned earlier) brought under suspicion any player whose golf-related activities showed a hint of favor or financial advantage in any way. After the trip, an article written by Casper Whitney in Outing magazine charged that both Travis and Arthur Lockwood should be declassed as “Professionals”. The article read, in part;

“…The conduct of Messrs. Travis and Lockwood in receiving hotel board and railroad transportation this spring, during a Florida golfing campaign, makes them obviously ineligible to rank as amateurs. By the rules of every amateur game, including golf, they are professionals, for, if they did not receive money for their services as touring hotel bill-boards, they did receive its equivalent in several hundred dollars worth of board and lodging and railroad fare.”

New USGA President R.H. Robertson, a friend of Travis, rushed to his defense. Interestingly, so did John Duncan Dunn, as the following June 1901 Rochester (NY) Democrat article illustrates;

Although he said nothing in public concerning the matter at the time, C. B. Macdonald held little back when he wrote his 1928 book, “Scotland’s Gift – Golf” a few years after Travis died;

“Stringent as the 1901 definition of amateur was, many thought it did not appear to contain any specific clause which directly covered the practice which “Outing” condemned, but the former Executive Committee intended it should.”

“We all know that President Robertson had not been imbued with the ancient and honorable traditions of the game in his youth any more than Travis had been, but we thought after their spending three months together in Scotland and England during the summer they would have absorbed some reverence for these same ancient and honorable traditions. We were doomed to be disappointed. As Rider Haggard said: “Golf, like Art, is a Goddess whom we woo in early youth if we would win her.”

Even viewed retrospectively and posthumously, Macdonald’s mention of Travis’s trip abroad to see and study the courses of Great Britain seems an odd one as it happened during the summer of 1901, months after the trip to Florida. It is difficult to understand what salutary or remedial benefit his visit abroad would have had on his past activities. Perhaps Macdonald was simply trying to make a clever literary point.

At the time, however, as will be seen, Macdonald and Travis continued as competitors, and were developing a friendship. Rumors of a big 1901 Macdonald/Travis match swirled during the spring of that year and whether the match took place or was simply the New York press encouraging a battle of Titans in their district is not known.

What is known is that by summer of 1901, Travis sailed abroad on an extended golf vacation to see the golf courses of Great Britain. Having learned the game on what were ostensibly the best golf courses in America at that time, it was a revelation to him from an architectural perspective. This detailed account of his travels appeared in an August 21st, 1901 Brooklyn Daily Eagle article.

On his return, Travis penned an 8-page article, resplendent with illustrative photographs and drawings for “Golf” Magazine, the official bulletin of the USGA. It read, in part;

“To visit the principal links in England and Scotland is a liberal education in itself. There you have golf – Golf in its best and highest form. Added to this, I have had the pleasure of seeing some of the very finest players in the world play on their native heath. Naturally, the whole thing to me has been a source of the keenest kind of enjoyment, and, incidentally, to a certain extent, more or less of a revelation and surprise. In this country it is difficult if not impossible, for the average American player to realize and properly appreciate the existent conditions of play on the other side as exemplified by their leading links, there being such a radical difference in their physical configuration in relation to our courses. I say courses advisedly, as few, if any, are true links in the proper sense of the word. It is highly doubtful whether any verbal or written description can adequately convey any accurate idea of the beauties of the simon-pure links which abound on the other side of the pond. We really have nothing like them.”

“…Golf, with us, is mostly of a kindergarten order. The holes are too easy, and there is too much of a family resemblance all through, generally speaking. There are undoubtedly some notable exceptions which will at once suggest themselves to those familiar with the leading courses on both sides. But, speaking by and large, our courses seem to be mainly laid out not with reference to first-class play, but rather to suit the game of the average player. And what is the result? On the ordinary courses a premium is placed on mediocrity…Really good links develop really good players, a few remarkably so, while the general standard of play is at the same time very sensibly improved. This fact is meeting with increasing recognition, as is evidenced by the growing improvement of our courses in the direction of making them more difficult…”

“..It is high time we awoke to a proper and appreciative realization of what real golf is – and constructed our courses accordingly”

Travis would go on in the fall of 1901 to again win the United States Amateur tournament, this time held at Atlantic City Country Club. For the first time, Travis played with the recently introduced, rubber-cored, “Haskell Ball”, and in the second round the long anticipated Travis/Macdonald match took place, with Travis dominating 7&6.

The following account of the match from the September 12th, 1901 issue of the Chicago Tribune;

In his 1928 book, Macdonald recounted events as such;

“The U.S.G.A. Amateur Championship was held at Atlantic City, September 9th to 14th. Travis had the low score, 157, and my score was 174. I won my first match 1 up, but meeting Travis in the second round I was beaten by 5 and 3. The semi-finals were most interesting, as they were between Travis and Douglas. Travis played with the Haskell and Douglas with the gutta. Travis won from Douglas at the thirty-eighth hole. My opinion is that it was the Haskell ball that won this tournament from Douglas. The magazine Golf, in reporting the semi-finals, said it was “more a case of ball against ball than player against player. There was a general impression that it was mainly to the use of the rubber-cored ball that Travis owed his victory. Douglas was playing a superb long game, the champion (Travis) would have been out-driven if he had stuck to the gutta, and he was generally outdriven as it was..” I share this view.”

The realization that perhaps his best playing days were probably behind him were significant to Macdonald in fundamental ways. Determined to stand up for what he saw as the proper and traditional values of the game as exemplified by the Royal and Ancient, Macdonald later wrote;

“The years 1901 and 1902 proved memorable ones in my golfing life, for the events which occurred in the golfing world at that time awoke me from a lethargic sense of existence, and in 1902 I determined that my solace lay in giving up the struggle to become the game’s master, but should rather become its servant. I concluded that was far better than upbraiding myself with the waste of time trying to compete in a supremacy my muscles would not respond to as the years slyly stole vigor from my limbs. This was my renunciation.”

“Secondly, the events of 1901 and 1902 fortunately gave me a happy thought, convincing me as they did that I could be of some service to the game of golf in America if by endeavor I could successfully implant into the player’s mind and heart the character of the game as I knew it as a boy in Scotland, ennobling and endearing as it has always been to me. President Robertson, advocating Americanized golf, advocating changing the constitution of the U.S.G.A., speaking slightingly of traditions and high sportsmanship. For twenty-five years I have faithfully worked to this end, and, I believe, with some degree of success.”

“Thirdly, inspired by the “best hole” controversy, which London Golf Illustrated put up to the leading amateurs and professionals of the United Kingdom, I conceived the idea of building the National Golf Links, constructing a course ideally built on classical grounds, trusting and hoping to be sufficiently successful so that it might lead to a better understanding of the merits of the game. Finally, in 1901 the Haskell ball became firmly established in the States and to a lesser degree in Scotland and England in 1902. These four influences reconciled me to be placed as a golfer in the “also-ran” class, and I was contented when after 1906 I was usually referred to in the reports of scratch golf event as among others “in the gallery”.