“…seeing the mystery traced like a watermark beneath the transparent surface of the familiar world…” – Henri LeFebvre

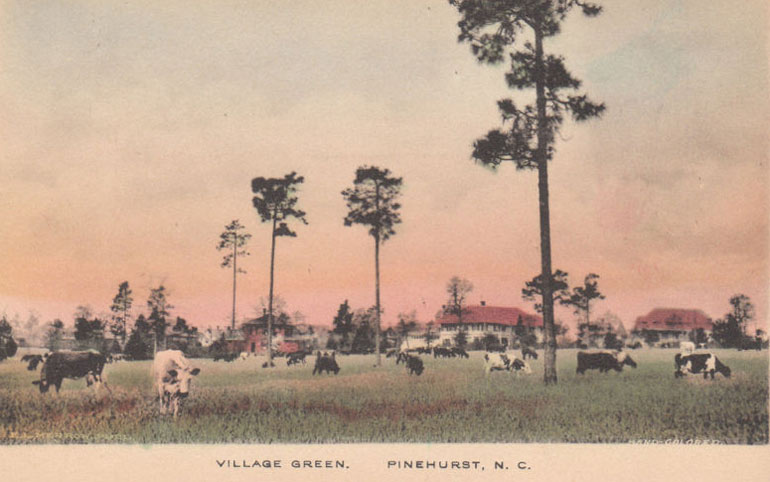

Unlike virtually all modern resort projects there was a noble dimension to the original Pinehurst concept. Certainly, commerce was a central concern but founder James Tufts was a man of uncommon character. Influenced in no small degree by his friend, Harvard clergyman Edward Everett Hale, Tufts sought to leverage the possibilities of his self made fortune in a manner that would benefit those of moderate income – with an emphasis on consumptives and their families. As their actions showed, Tufts and Hale were not mere gentlemen. They embodied characteristics that eluded lesser minds of the peerage. Well heeled New Englanders had long since found their passage from the brutal climate that hammered the region for months on end. Now through Tuft’s sweeping initiative many others might find their own satisfying measure of respite as well.

Golf was not even a remote consideration in the initial vision of Pinehurst. The original intention was to establish such a place in Florida. The image of that sun drenched peninsula must have loomed large in the minds of even the most stoic New Englanders. However, as with all epics, destiny crept into the story with results that play out even to this day. In our story destiny appeared in the form of various friends of Tufts returning to Boston with stories about an obscure region of the Mid South. One friend in particular had a wife that suffered considerably from the consumptives disease – tuberculosis. Upon her return from a lengthy Southern visit Tufts was more than a bit taken by her glowing health.

Following the nearly miraculous recovery which he witnessed first hand, Tufts made a proper survey of this Southern region for himself. Finding what he perceived to be favorable conditions all around he ultimately purchased a very large tract for his proposed resort. The natives who sold him the land thought they had taken our Bostonian out for a bit of a ride. After all, the area was a wasteland due to the logging and the “boxing” of trees for the extraction of “naval stores”, ie.turpentine, tar and pitch used primarily on ships. They could not see what possible use this chap could have for such a place. But then, they did not have Tufts visionary capabilities.

And so, this industrious man began construction of an entire village.

Well, no sooner had he become irretrievably committed to the mammoth project than he discovered something which negated the entire purpose of the undertaking.

As forward thinking as Tufts and Hale were there was no way they could have foreseen the latest evolutionary turn in medical knowledge. For just as the town was being constructed in 1895 the disease of the consumptive – tuberculosis – was found to be communicable rather than hereditary. Under the hands of lesser mettle the entire affair would have turned into a fading ghost town. Since the matter fell under the purview of James Tufts this American story turned out rather differently.

With the original concept exiting the stage he turned to alternate plans for the town that some termed “Tufts Folly”. Golf was still not under consideration at this point. His latest concept was…peaches.

A great fortune and many man hours went into creating this proposed peach empire. Fortunately, this too went the way of the consumptive concept. The culprit in the latest debacle was a pest known as the “San Jose Scale”. A large infestation of these little beasts put a definitive end to the peach concept.

And so, yet again, Tufts found his grand plans turned to dust. At this point our protagonist was getting on in years – and with rather bleak prospects on the horizon. However, the solution for the unenviable scenario was just around the corner – in the form of an irate farmer.

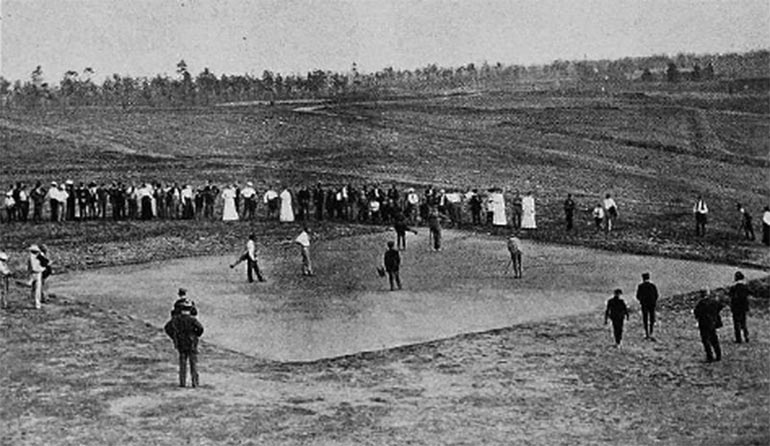

Confined as he pretty much was at this point to his suite in the Carolina Hotel – the largest wooden structure in the state – Tufts was obliged to field a complaint from the farmer. This unknown man regaled the patrician with a story about how some visitors were disturbing the cows with a curious game…

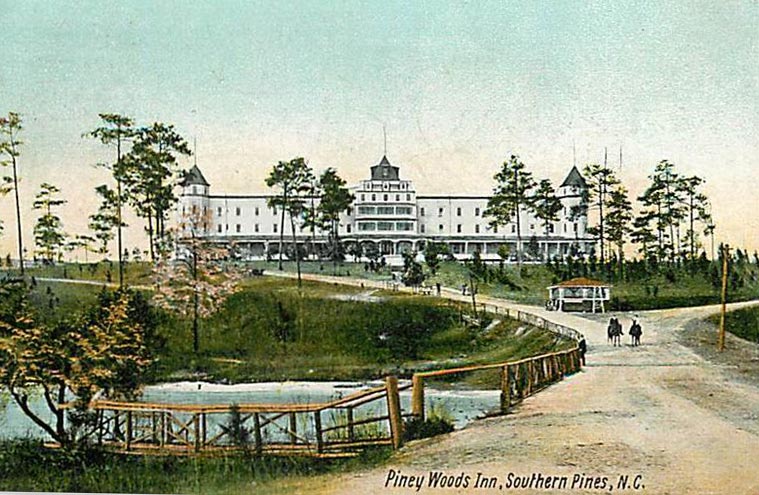

Not being the sort to take things by half measures, James Tufts wasted no time in seizing upon the idea of this unusual game. In short order he drafted a man by the name of Dr. Leroy Culver to design a nine hole run for resort guests. Culver – who had been an NYC public health official – was chosen because he had visited St. Andrews and had sound ideas regarding the game. It is not well known that, while resident physician, Dr. Culver also designed a small golfing area at the Piney Woods Inn in neighboring Southern Pines.

The “course” at the Piney Woods Inn where according to their advertising ” nervous women are inspired with new life, and where the little people imbibe vigor with every breath” – as well as the remarkable structure itself are no longer with us. A pity because from its lofty perch on the edge of downtown it lent more than a measure of the dramatic to the proceedings. Starry eyed recollections by a few of the old timers said that in the full swing of evenings in season when the building was glowing at night and strains of music and laughter drifted out of the ballroom and through the sleeping pines that it seemed like something more out of a dream than real life.

Rather Fitzgeraldean – in fact, F. Scott himself was present during the era. He had the same editor as Southern Pines author James Boyd. Maxwell Perkins dispatched the Great Gatsby to the Sandhills in hopes that Boyd’s sensible approach to the profession would influence his wayward magician. It did not work but Fitzgerald did make quite an impression making an inebriated leap over a hedge in Pinehurst to a party “wearing a blue sport coat and white duck pants”.

Boyd was known as an arch equestrian. The founder of the highly regarded Moore County Hounds actually had an estate more than a little similar to the Overhills affair just a few miles east. The equestrian world which is as vital today as in yesteryear does not remember the fact that this exemplary gentleman not only played golf – but, like Overhills, actually had his own course to match his extensive fox hunting grounds.

By the way, the worlds oldest known longleaf pine is situated in the area of Boyd’s fox hunting grounds which now make up Weymouth Woods State Park. The tree is approximately 500 years old. The golf course is no longer with us.

To return from our little sideways stroll through a contemporary sense of the area, Tufts consulted with some of the substantive employees that made up the upper tier of his staff regarding his intention to pursue the transplantation of the Scottish game to the backwoods of North Carolina. They unequivocally assured him that this game of golf was nothing more than a fad and to pursue it as core pillar of the resort was quite foolhardy.

Tufts thanked them for their collective wisdom, promptly dispensed with it and summoned Dr. Culver for the purpose of sorting out some proper links for his guests. While the echoes of their approbation rang around the back rooms of offices the first Pinehurst golf course took shape in very short order.

As was stated before, Culver was chosen because Tufts thought he had a solid grasp of how a proper course was supposed to be set up. Here are some quotes from Dr. Culver:

“A nine hole course has been laid out after the famous St. Andrews.”

“To be sure groves of trees beautify the landscape, but mar the joy of the game.”

“There are no links in the South to be compared with those at Pinehurst, and they will prove the great magnet of attraction to lovers of the game.”

In spite of the lofty rhetoric and theory the first nine hole course – which debuted in 1898 – was a very primitive effort. This does not mean to imply that it was not a worthy endeavor because allowing the purity of the land to speak for itself rather than the sophisticated artistry of future design masters had its own considerable appeal. Never the less, the original course was essentially a field with tees and square sand greens strewn about. A humble beginning – but a beginning none the less.

Unlike the previous resort concepts, fate treated Tufts more kindly with this new sporting approach. In fact, it became such a draw that a new nine was required later that very same year – lest the guests get frustrated with those ghastly three hour rounds. For the design of the additional nine holes Tufts turned to the new golf professional by way of Scotland. His name was not Donald Ross.

John Dunn Tucker hailed from the Dunn golfing family of Musselburgh, Scotland. To give you an idea of the significance of Musselburgh – consider the fact that Mary Queen of Scots played golf there in…the 1500’s. It is, in fact, considered the worlds oldest course. And so, from its earliest days Pinehurst bore the imprint of the most authentic of golfing traditions.

The Tucker family featured several accomplished golf professionals. They were associated with many links within the British Isles – chiefly North Berwick. But their reach did not stop at the shores of the Atlantic. The family was involved in several substantial courses in the States. In particular, Tucker’s cousin Willie Dunn was responsible for several highly rated designs. The most notable of these being a place on the farther reaches of Long Island called Shinnecock.

This new Pinehurst nine drifted out into a rolling terrain that is among the best in the area. Within this sandy loam Tucker formed intriguing corridors which are largely in play to this day. Over many years, his successor Donald Ross went on to slowly craft this course into what made for quite a compelling round. It ended up – then as now – right in front of the clubhouse veranda.

As with other esteemed Pinehurst courses time and less traditional perspectives led No.1 Course away from its Scottish heritage. Like No. 2 Course the original magic became more than a bit covered up. Also like No. 2, its potent appeal is not lost to history but waiting for proper hands to bring the graceful artistry back into focus.

Even before Ross brought the course up to the praise worthy level it ultimately reached, the course received high regard from many quarters. Harry Vardon himself was most favorably pleased when he played several rounds there during his 1900 tour of the former colonies.

Vardon was but one of many who found their way to the isolated community from places far afield…

Not being the sort to take things by half measures, James Tufts wasted no time in seizing upon the idea of this unusual game. In short order he drafted a man by the name of Dr. Leroy Culver to design a nine hole run for resort guests. Culver – who had been an NYC public health official – was chosen because he had visited St. Andrews and had sound ideas regarding the game. It is not well known that, while resident physician, Dr. Culver also designed a small golfing area at the Piney Woods Inn in neighboring Southern Pines.

The “course” at the Piney Woods Inn where according to their advertising ” nervous women are inspired with new life, and where the little people imbibe vigor with every breath” – as well as the remarkable structure itself are no longer with us. A pity because from its lofty perch on the edge of downtown it lent more than a measure of the dramatic to the proceedings. Starry eyed recollections by a few of the old timers said that in the full swing of evenings in season when the building was glowing at night and strains of music and laughter drifted out of the ballroom and through the sleeping pines that it seemed like something more out of a dream than real life.

Rather Fitzgeraldean – in fact, F. Scott himself was present during the era. He had the same editor as Southern Pines author James Boyd. Maxwell Perkins dispatched the Great Gatsby to the Sandhills in hopes that Boyd’s sensible approach to the profession would influence his wayward magician. It did not work but Fitzgerald did make quite an impression making an inebriated leap over a hedge in Pinehurst to a party “wearing a blue sport coat and white duck pants”.

Boyd was known as an arch equestrian. The founder of the highly regarded Moore County Hounds actually had an estate more than a little similar to the Overhills affair just a few miles east. The equestrian world which is as vital today as in yesteryear does not remember the fact that this exemplary gentleman not only played golf – but, like Overhills, actually had his own course to match his extensive fox hunting grounds.

By the way, the worlds oldest known longleaf pine is situated in the area of Boyd’s fox hunting grounds which now make up Weymouth Woods State Park. The tree is approximately 500 years old. The golf course is no longer with us.

To return from our little sideways stroll through a contemporary sense of the area, Tufts consulted with some of the substantive employees that made up the upper tier of his staff regarding his intention to pursue the transplantation of the Scottish game to the backwoods of North Carolina. They unequivocally assured him that this game of golf was nothing more than a fad and to pursue it as core pillar of the resort was quite foolhardy.

Tufts thanked them for their collective wisdom, promptly dispensed with it and summoned Dr. Culver for the purpose of sorting out some proper links for his guests. While the echoes of their approbation rang around the back rooms of offices the first Pinehurst golf course took shape in very short order.

As was stated before, Culver was chosen because Tufts thought he had a solid grasp of how a proper course was supposed to be set up. Here are some quotes from Dr. Culver:

“A nine hole course has been laid out after the famous St. Andrews.”

“To be sure groves of trees beautify the landscape, but mar the joy of the game.”

“There are no links in the South to be compared with those at Pinehurst, and they will prove the great magnet of attraction to lovers of the game.”

In spite of the lofty rhetoric and theory the first nine hole course – which debuted in 1898 – was a very primitive effort. This does not mean to imply that it was not a worthy endeavor because allowing the purity of the land to speak for itself rather than the sophisticated artistry of future design masters had its own considerable appeal. Never the less, the original course was essentially a field with tees and square sand greens strewn about. A humble beginning – but a beginning none the less.

Unlike the previous resort concepts, fate treated Tufts more kindly with this new sporting approach. In fact, it became such a draw that a new nine was required later that very same year – lest the guests get frustrated with those ghastly three hour rounds. For the design of the additional nine holes Tufts turned to the new golf professional by way of Scotland. His name was not Donald Ross.

John Dunn Tucker hailed from the Dunn golfing family of Musselburgh, Scotland. To give you an idea of the significance of Musselburgh – consider the fact that Mary Queen of Scots played golf there in…the 1500’s. It is, in fact, considered the worlds oldest course. And so, from its earliest days Pinehurst bore the imprint of the most authentic of golfing traditions.

The Tucker family featured several accomplished golf professionals. They were associated with many links within the British Isles – chiefly North Berwick. But their reach did not stop at the shores of the Atlantic. The family was involved in several substantial courses in the States. In particular, Tucker’s cousin Willie Dunn was responsible for several highly rated designs. The most notable of these being a place on the farther reaches of Long Island called Shinnecock.

This new Pinehurst nine drifted out into a rolling terrain that is among the best in the area. Within this sandy loam Tucker formed intriguing corridors which are largely in play to this day. Over many years, his successor Donald Ross went on to slowly craft this course into what made for quite a compelling round. It ended up – then as now – right in front of the clubhouse veranda.

As with other esteemed Pinehurst courses time and less traditional perspectives led No.1 Course away from its Scottish heritage. Like No. 2 Course the original magic became more than a bit covered up. Also like No. 2, its potent appeal is not lost to history but waiting for proper hands to bring the graceful artistry back into focus.

Even before Ross brought the course up to the praise worthy level it ultimately reached, the course received high regard from many quarters. Harry Vardon himself was most favorably pleased when he played several rounds there during his 1900 tour of the former colonies.

Vardon was but one of many who found their way to the isolated community from places far afield…

In a pattern that continues a century on, it became necessary accommodate the almost feverish enthusiasms of guests so keen upon the fad which had been dismissed by Tufts lieutenants. By 1907 what was called “the New Course” made its debut. The early version – which was subsequently named No. 2 – received considerable design attention by a golfing genius who emigrated to the States from…Australia.

Virtually all of golf’s notables in this era (and every succeeding era) have made their pilgrimage to Tufts inadvertent golfing kingdom. This is another early theme which is still being played out in the same fashion it has since the beginning. That is, since the 19th Century the area has been a magnet for remarkable people who have gone on to make it their home – thus taking the social world of this remote area to a quantum level one would be hard pressed to match in the overall region. Let’s have a look at Henry Longhurst’s take on the matter:

“In clearings off these roads, each protected from the prying eye of the populace by a fringe of pines, are specimens of those lovely, white Colonial-style American homes familiar to the British film-goer. General Marshall rents one. Dick Chapman, the British Amateur champion, and his conversational wife, Eloise have another, and so has the hospitable Earl of Carrick.

As to the others, what with Singer Sewing Machines, Heinz’s 57 Varieties (surely more by now?), Somebody’s Ball Bearings and Somebody Else’s Motors, the guide on my privately conducted tour might have been reciting from a handbook of the industrial nobility.”

The Marshall he was referring to would be the Marshall who saved a place called…Europe. Truman and Eisenhower used to visit Liscombe Cottage cottage to pay homage to this colossus. The park in front of the clubhouse is named for him…even though he didn’t actually play golf.

The list of striking individuals who have gravitated toward the area goes on and on – as do the ramifications. However, there once was an Australian who spent a great deal of time in Pinehurst that deserves consideration in regard to the earliest years.

Walter Travis was born in that beautiful country in 1862. At the age of 23 he made the great journey to his new homeland in the States. Twelve years later – most reluctantly and only out of social and business obligation – Travis had his first go at the sport. Within seven months he had won his first tournament. He went on to win dozens more. Among them were four majors – three U.S. Amateurs and one British Amateur. Travis was the man a young Bobby Jones sought out for putting advice – and learned the inverse overlap from. This is what Jones had to say in his autobiography Golf is My Game:

“The Grand Old Man of the putting green, certainly has better right than anyone to be recognized as the master putter of all time.”

It is a little difficult to believe that a man who played on such an all time level could match those competitive achievements in other areas of the game…but that was the case.

According to the USGA:

“After his playing career ended, Travis put his permanent stamp on the game, writing books and articles, one in fact that helped shape the course rating and handicap systems used today. He later became editor of the highly acclaimed The American Golfer, viewed in some circles as the best-ever golf magazine.

Moreover, he proved to be a genius and a visionary when it came to course architecture, ranking with Charles B. Macdonald as one of the most influential men in the early days of golf. “

Travis was an authentic golfing renaissance man and fin de siècle Pinehurst was the ideal place for such a person. As a very close friend of the Tufts family and a frequent playing partner with Donald Ross, Travis was a key member of this Southern golfing society. It is generally conceded that he gave no small amount of input to Tufts and Ross regarding the earliest iteration of No. 2.

To get a sense of what occurred in that first era lets consider these highly provocative words directly from an article Travis wrote in a 1920 edition of American Golfer:

“A history of the number two or championship course at Pinehurst may not be inappropriate. For several years I had been at Mr. Tufts, the proprietor, to make this an exacting test. The course was originally designed for ladies. The distances on the hole were fairly good and capable of extension, but there wasn’t a single bunker. It was so tame and insipid that there was practically no play over it. Everyone preferred the number one course, which, comparatively speaking, had some teeth to it.

The suggestion did not meet with favor. Mr. Tufts had an idea that the class of players who visited Pinehurst did not want anything too severe. I thought otherwise. Finally in 1906 I won him around to my way of thinking and he gave me carte blanche to go ahead. I knew the changes that I had in mind would result in a great uproar at the start, and I didn’t feel like shouldering the whole responsibility, so I suggested that Donald Ross and I should go over the course together and, without conferring, each propose a separate plan. I knew what the result would be.

For some time I had been pouring into Donald’s ears my ideas; in point of fact, I had urged him to take up the laying out of courses, as with the certain development of the game a fine future was assured for having a bent in this line. In those days Willie Dunn had ceased to figure and his successor, although credited with laying out some hundreds of courses all over the country, really had no genius for the work. Donald heeded my advice…and golf has been tremendously benefited by his many very fine creations since. However, I am digressing.

At that time he was merely an echo of my own views regarding the fundamental principles of golf course architecture. Whereas the Willie Dunn system called for compulsory carries for both tee and second shots, I was an advocate of optional carries; that is to say, I believe, in the principle of giving the player a choice of carrying a bunker or playing safe. But if he elected to play safe on the tee shot, he would be confronted with the same problem on his second shot.

So I felt quite certain of what would happen. Donald and I were a unit. And the course was bunkered accordingly, with one exception, and that was on the twelfth hole. Here I planned three avenues of play, down the middle, narrow with a big bunker a hundred and eighty yards from the tee, leaving a clear second to the green; at the right quite wide, the second shot having to carry over a bunker at the edge of the green. It was quite revolutionary in those day, such a big carry, but it was decided to construct the hole as outlined. When he came to it, however, Donald’s courage failed him; he weakly compromised by making a straightaway affair of it, with a bunker at the right some hundred and sixty yards from the tee, which didn’t mean anything.

What was the result of this stiffening up? Men who ordinarily did number one course in the lower 80’s tackled number two. Up ran their scores in the high 90’s, possibly over the century mark. Disgusted, they emphatically declared they were through—it was a course only for experts. But— and here lies the lure of the game, challenging the player to match his skill against difficulties—a little sober reflection, pique, never-say-die, or something or other rushed those same men over to number two the first thing the following day, in a laudable effort, also mostly vain, to beat that 97 of the previous day. And at it they kept day after day. Whereas the problem had been how to get players from number one to number two, now a new one presented itself—how to get them back to number one—which was finally solved in a way by stiffening up number one.”

—

The main thing one can deduce from this striking passage is that it is unlikely Mr. Travis suffered from a shortage of ego. Indeed, it is the imperious tone (“he was merely an echo of my own views”) which draws the credibility of his statements into question. Any discriminating reader would view his words with no small measure of skepticism. It is interesting to note that genius and graciousness are not the most compatible of personal characteristics. Some manage to pull it off – but that is the exception rather than the rule.

However amplified his views may have been, there is no denying the fact that his panoramic vision and capability far exceed that which we are accustomed to today. There are only a few contemporary golfers who have been able to transpose their brilliance from one area to another – most notably Arnold Palmer who matched his playing prowess with a personal magnetism so great that he almost single handedly moved the quaint Scottish game from the elite fringes of society to the center of world culture.

That this chap could have used a measure or two more in the department of circumspection will have to be taken within a larger context. That context being he did have extraordinary talents and he contributed the full measure of this to the game that means so much to so many.

Regarding the story at hand, this little incendiary which Travis tossed over the wall of American Golfer does highlight the fact that the story of the early days is more complex and colorful than one might suppose.

Although no one can not say that today’s course is reflective of the Travis design perspective, he most certainly was one of the more intriguing elements of the story of this course which has so many chapters. The significance of his participation in the construction of what ultimately became one of the masterworks is not so much what design or routing that might retain ghostlike remnants of his participation. For that is likely minor at best. The real significance is in the story itself rather than in the design. That is, when people reflect upon the epic life of Pinehurst No. 2 they tend to portray this icon as a more cut and dried affair than it was. In actuality, it is a meandering tale which wandered here and there for decades through those longleaf pines, before ultimately, in the mid 1930’s, finally coalescing into the form which made it one of the penultimate courses.

Whether one believes Mr. Travis excited recount of the genesis or not, the magic of No. 2 is in the last fifty yards of the holes. There is very fine work which occurs before one contends with those enigmatic green complexes but it is the later which distinguish the course so spectacularly. That wizardry occurred after our Australian exited this Southern stage.

Never the less, when reflecting upon this masterpiece, Mr. Travis merits some measure of consideration.

Fownes and Travis are intriguing aspects of this particular chapter of the resort. How many more compelling elements can be found within the sepia toned annals? Far more than could possibly be related in this essay. Well, this article may not sufficiently portray the full story, but it should make it clear that the beginning – as well as subsequent chapters – are far more textured than even a substantive review of what remains recorded could tell. And so, that will have to suffice for moment. It’s time to bring this version of the early world which Tufts begat to a close.

Epilogue

When people discuss the timeless idyll that wanders through a forest which seems to go on forever, they will remember the fellow who wore knickers that made the famous putt – and kicked his leg up toward heaven in the most pure display of joy and redemption you will ever see. Even those not so conversant with golfing ephemera will vaguely recall the Scot who formed those legendary sporting fields. When they make their pilgrimage they will hear the chimes of the clock tower slowly cast its resonant spell throughout the town and across the links. They will miss the intricately detailed mosaic that is the authentic story of Americas once and future home of golf. For Pinehurst is not a conglomeration of stark facts. It is a mythic realm where the presence of the immortals who have passed through is palpable – and quickens the spirits of those who enter.

THE END

![]() Chris Buie is the author of The Early Days of Pinehurst

Chris Buie is the author of The Early Days of Pinehurst

Many facts contained within are derived from Richard Mandell’s book “Pinehurst – The Home of American Golf”. Most of the images are courtesy of the Tufts Archives. Both are first rate affairs which are more than worthy of your patronage.

Also referenced are Oakmont, 100 Years by Marino Parascenzo and the Garden City Golf Club Book. The Longhurst section is from Herbert Warren Wind’s compendium The Complete Golfer.