Cape Breton Highlands – 1937 to 1941

by

Ian Andrew

February 2017

George Knudson called Cape Breton Highlands “The Cypress Point of Canada for sheer beauty.” In 1965, George Knudson was asked to come to Cape Breton Highlands to play Al Balding in a match for Shell’s Wonderful World of Golf. He was so enamoured by the setting that he later said to Lorne Rubenstein that he loved the place so much he’d be happy to walk it with his wife Shirley and have a picnic there, never mind playing.

I first saw the course in 1981. I had told my father I wanted to be a golf course architect and he decided that we should make a series of family trips based around playing famous golf courses. My mother never forgave me for this. Cape Breton Highlands was the first great golf course I ever saw. It was in the middle of the mid-summer, very brown, the ball bounced along the ground all day and I was awestruck by the views of the mountains and ocean.

Origins to Opening

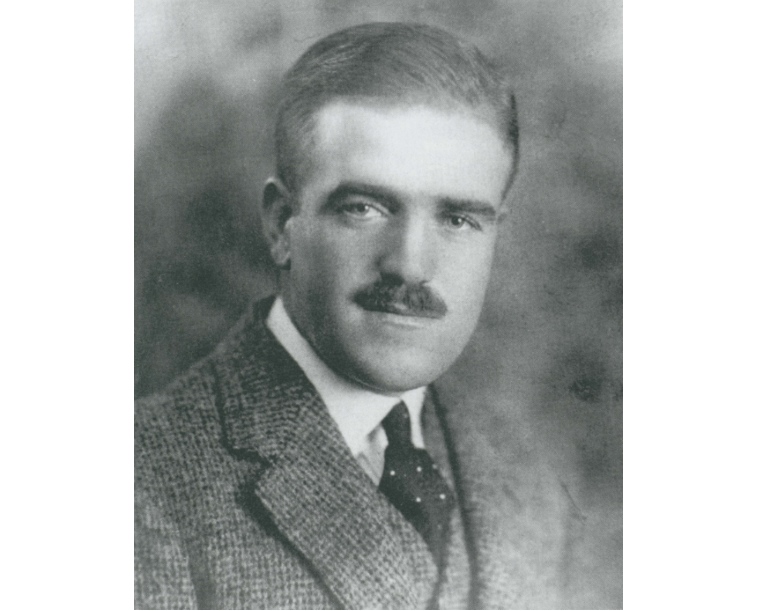

In the middle of the 1930’s Stanley Thompson was having trouble finding new golf course to build. He saw the Canadian government as the last remaining source of available money in Canada. Cape Breton Highlands National Park was established in 1936 and Prince Edward National Park was in the middle of establishment in 1937. Never one to miss an opportunity, Thompson conceived the idea of building courses for the new National Parks. Not only would they provide recreational opportunities for visitors, but he could sell the projects as make-work projects for the hardest-hit communities just outside the parks.

According to step-daughter Pat Howett, Stanley Thompson was able to arrange a meeting with Prime Minister Mackenzie King at his office. He was able to use was his mother-in-law’s friendship with Isabella King, the prime minister’s mother, as an introduction. Mackenzie King was famous for his obsession with his dead mother and agreed to a visit. Stanley presented the idea of building new courses in the National Parks as a way for the government to provide much needed employment for the regions.

Thompson convinced Jim Smart of Parks Canada that it was economical to build both new courses in the parks at the same time. One would be built near Ingonish and the other would be built adjacent to Anne of Green Gables homestead in Prince Edward Island. Since they were both make-work projects, the construction would be completed largely by hand. At Highlands, the equipment was limited to one steam shovel, one bulldozer, and a few dump trucks. The equipment was to be used sparingly to make sure the project employed the maximum number of people. The contract specified a maximum of 20 hours a week.

Stanley Thompson came to Ingonish in 1937 to plan the course. He was told to keep it within the established park boundaries. Thompson brought with him a 1936 aerial of the site and set out to review the available land. The setting was quite different from how we know it now. The upper hills were fully treed, but still recovering from being logged for hardwood to shore up the Sydney Mines. There were almost no hardwoods down below, but there were stands of conifer throughout. The setting was far more open than we think of it today. You could see most of the undulations in the land and there were magnificent views into the mountains and out to the ocean. The problem Thompson faced was the best land was often not in the park’s boundary. Stanley quickly figured out the only way he was going to build a golf course was to utilize some of the active farms.

But timing was everything for all involved. Thompson’s business was struggling and he had done very little new construction work since the completion of Capilano in 1935. He was surviving mostly on building small nine-hole courses for Northern Ontario Gold mining communities. And this was the first significant commission in quite some time.

The community was still reeling from the recent dramatic collapse in the fishing stocks. This came at the start of the depression. The town’s economy was faltering and many younger people had begun to flee to the cities to find work. In Eastern Canada this was a period where many small isolated communities were abandoned and often the residents were compensated to leave and begin somewhere new. Cape Breton Highlands National Park had just being established, but was not yet a source of local employment. The Cabot Trail Road existed, but it was still a very harrowing journey over rough and dangerous ground.

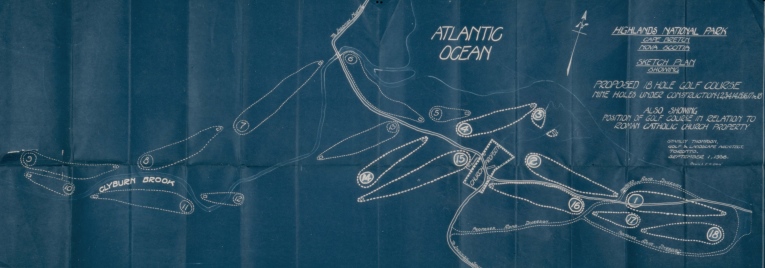

Stanley’s initial routing was done right on top of the aerial. Stan laid out rough tee locations, the centreline for the holes and used circles to represent the green sites. Once he felt he had a working plan, he headed back to the Allister MacLeod’s Hotel in North Ingonish to produce a more detailed plan with tees, bunkers, fairway lines and greens. This tracing would then be taken back to the office of Wilson, Bunnell and Borgstrum Limited who would clean-up the plan for presentation.

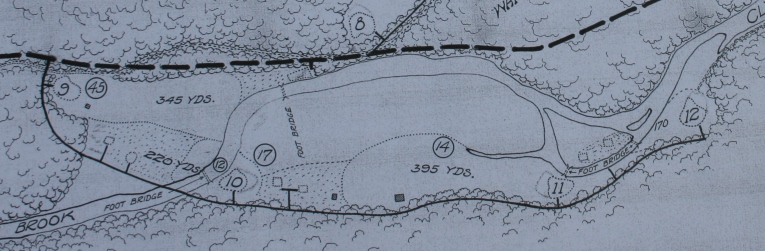

The course was supposed to be set completely inside the park boundaries, but as Geoff Cornish put it, “this didn’t make any difference to Stan.” Stanley had created an 18-hole routing that followed the path of least resistance through some very severe terrain. The initial nine known as the Short Loop (Holes 1-4 and 14-18) began and finished on the Corson Estate on Middle Head. It required utilizing a series of small farms located between Middle Head and the Cabot Trail. The Doyle’s for the 18th, the Dauphinee’s for the 17th, the Donovan’s for the 16th and the Dauphinee’s for the 4th.

The Long Loop (Holes 5-13) utilized a series of farms along the Clyburn Brook beginning at the estuary and running up to the base of Ben Franey. It was the Daphinees again for the 5th hole, the MacNeil’s for the 6th and 7th, the Brewer’s for the 13th, the Doucette’s for the 11th, the MacDonald’s for the 10th and the Donovan’s for the 9th. All told, his layout involved the expropriation of 30 different properties.

Henry and Julia Corson sold their estate to the park around the end of 1937. Parks Canada had coveted this location and made an immediate purchase. The Corsons were paid right away and compared to others, the family were well compensated for their land. Jim Stuart approached Stanley about having the second nine holes to go out on Middle Head and back. But Stanley felt the point was too narrow for adjoining holes and knew it was too tough and expensive to build there. Robbie Robinson would push for the same idea, but Stanley told him he wasn’t interested. The other consideration was trying to string holes down the coastline, beyond the current 6th hole, but that option was never feasible. Stanley’s budget could not afford the cost to relocate the town road and this would have expropriated land from far more families.

The plan was approved in principal. The expropriations would eventually be handled by Wilfred Creighton. Stanley Thompson had the first nine approved and wanted to get underway. According to Geoff Cornish, he asked Peter Dauphinee to tell the owners, “I’ve got a job for you now – the federal or provincial government will pay you someday for your land—I will assure you of that.” Since the community respected Peter, and knew he too was facing expropriation, they trusted everything would work out for the best. They were in the middle of the Depression, so the promise of steady work and payment for their land probably seemed like their best option. Once they agreed, Thompson immediately put the men on the construction team and began paying them 30 cents a day, a good wage for the era. The income turned out to be critical since it took a very long time for them to get reimbursed and they ended up counting on the income to survive and rebuild.

Thompson finalized The Short Loop and placed bunkers on the plan. Geoff Cornish mentioned that Stan did produce a few green models, but not a full set unlike Capilano. The original budget for the Short Nine submitted to Council was set at $57,500. The budget for the Long Nine was estimated at $70,000. The budget for all 18 holes was $127,000. Cornish remembers the overruns turning out to be $40,000, and the final cost being closer to $180,000 with the comment that the bridges ended up playing a significant role in the final cost.

The largest number of workers on site at any point was 180 men. The crew worked 10-hour days with an hour off in the middle for lunch. Some went home and others had their families walk down to the site and join them to eat. Cornish estimates the number of different people working on the site from start to finish was around 375. But that may have included the 100 young men hired for Sydney to build that section of the trail system for the National Park. Peter Dauphinee continued to play a critical role in the selecting the men as well as being the liaison between the Toronto crew and the Ingonish crew.

In the second-year the payroll was handled on site by Bill Stuart, who was Stanley’s business manager. He had come to check expenditures and he may have actually been an active business partner in this project. Bill was originally an engineer, who had been secretary to Sir Henry Thornton of the Canadian National until 1932. It is highly likely that he met Thompson while Jasper Park was being renovated. Bill was the man who designed and built the famous swinging bridge that crossed the Clyburn Brook between the 10th green and 11th tees. His construction assistant was none other than Peter Dauphinee.

Geoff Cornish says he was able to see most of the holes prior to starting construction. The only really significant tree removal on the Short Loop was for the 1st and 2nd and 16th fairways. The Long Loop required even less clearing since the Clyburn Valley was wide open from the mountain to the banks of the Brook. The only really significant clearing required was for the 7th and 8th holes.

Work began in August 1938 with Hennie Henderson acting as the lead foreman. He was an engineer who was often given the task of organizing a project. He began to clear the site, organizing the construction teams and worked out the logistics for distributing soil around the property. According to Geoff Cornish, Thompson preferred to begin projects with an engineer and then to transition to an associate once the finishing stages had begun. Robbie Robinson was in charge of both projects for Thompson, but, in reality, it was Hennie’s site to organize and then Geoff’s site to finish. For Geoff, this included establishing and growing in the turfgrass too. The initial golf superintendent was Bert Donovan from the community.

Stanley kept in touch regularly by telegraph and he came to Atlantic Canada once a month by train. He would ride out to Sydney and then take a coastal steamer called the Aspy out to Ingonish. Geoff said that as soon as he arrived he was hands on, He would demand a crew to be available to make changes. Geoff recalled, “He would do a lot of those bunkers personally. And, then, the rolls in the green. We never seemed to have those right. He’d changed them all when he arrived.” He mentioned that Stanley would give him instructions before he left, always asking why Geoff was writing things down. He would return and inevitably remark: “That’s not right – that’s not what I wanted at all.”

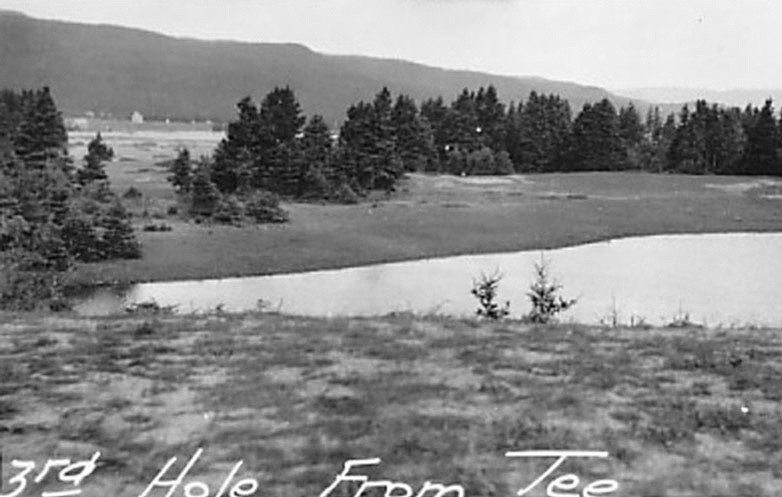

Construction began on the 2nd hole in August of 1938. The goal was to build and hopefully grass most of the Short Loop. When they reached the 3rd green, Geoff brought up the fact that the green had flooding a few times during construction. He asked, “Wouldn’t it be better is we raised her two or three feet?” Stan’s answer was a simply no. Thompson went on to stress that he wanted the greens at Cape Breton Highlands to be built on the ground.

Geoff recalled another occasion in 1939 where he met with Stanley and Robbie out at the 10th hole. Robbie had decided that the tenth green would be better placed across the river against the mountain. Geoff said he agreed with Robbie. Stanley reminded them both that it was not where he wanted the green and that they better get it built if they wanted the chance to finish it before he left. Geoff said Stan knew exactly what he wanted and wasn’t looking for any input.

Geoff became the Project Supervisor in 1939 and they were now into the construction of the Long Loop. Stanley had convinced Parks Canada that the course had to be 18 holes to be successful. That spring Stanley asked Geoff to get up to the site in March, so they could get an early start. Geoff arranged a train to Sydney and then vehicular transport, through a post office, to Ingonish. They could only get to St. Ann’s Bay, so he stayed overnight and was introduced to sled dog trainer who said he could get Geoff there. They took the dogsled 35 miles over Mount Smokey to Ingonish arriving to find the site under four feet of snow.

Geoff had a degree from the University of British Columbia in Agronomy. Stanley had brought him to Capilano to access the soils. It was only logical that Stanley put Geoff in charge of selecting the best soil for the greens at Highlands. He supervised the removal of 12,000 cubic yards of river silt from the 6th fairway and another 700 cubic yards from the Clyburn Valley above the course to be distributed around the site. The best soil was saved and used for the greens. Geoff mentioned that the greens were rock hard early on, but Robinson says after the Second World War they were able amend the greens with sand and improve the soil characteristics. The remainder of the topsoil was used to build tees and to cover the rocky outcrops in the fairways and roughs. Everything was hand-raked and stones were hand-picked before seeding.

The course was seeded to fescue and New Zealand Brown Top (Bent), but the fescues quickly died out giving way to poa annua. They got the seed from Blondie Wilson, who at one time worked directly for Stanley. They planted fescues and Kentucky Bluegrass on the fairways and the same blend for the rough. They established fairway lines by mowing. The fairways were seeded with a wheelbarrow seeder and then rolled with a homemade roller built from spare parts by Neil Donovan.

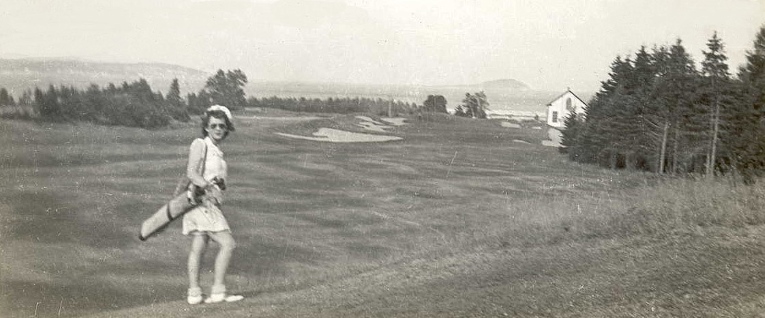

Thompson had also sent Ken Gullan to assist Geoff. He was from Gullane, Scotland, and his role was to give the course “a definitive links look.” Geoff recalls that he was a few years older than Stan and the one person who could confront Stan when he felt it necessary. Ken transplanted Marram grass from around the area onto the golf course to add a links feel. There were lots of locations in the area where the grasses could be found, dug up, and transplanted back onto the site. There are still large stands right of the 6th hole, but the biggest architectural loss was the removal of the marram covered sand dunes on the 4th hole for topdressing sand.

Stanley kept a set of clubs at the construction site, which are still there today. He used to hit shots periodically to test out holes. He was still a fine player at this point. Geoff eventually played the course during the grow-in, but went off to war soon after. The golf course officially opened in 1941 with Thompson being present at the event. With resources becoming scarce and no visitors to support the course, they had to close the Long Loop in 1942. They scaled the maintenance down to the minimum on the remaining holes. The holes were eventually brought back into play in 1946. After the war, Thompson made regular trips to Eastern Canada to review courses for the railways and he often included a stop at Highlands Links. There don’t appear to be any modifications made in the period before his death in 1953.

The Course Layout

One of the unusual aspects of Cape Breton Highlands is the number of truly unique landscapes it traverses in 18 holes. The golfer receives a walking education on the region’s geography. When Stanley surveyed the property on foot, he must have recognized how different each section was from the previous. Whether intended or by circumstance, he ended up telling this story a chapter at a time.

The initial six holes begin out on the headland with a wide panorama of the ocean. The holes that follow work their way in and out of the conifers rewarding the players with one epic vista after another out to the ocean. As the holes progress, they work increasingly closer to the sea culminating with the last one playing right alongside the Clyburn Estuary.

After the sixth green, you head inland and have a moment to relax as you enter the forested highlands. This is the first change of setting. When you step out into the opening at the 7th tee you are completely taken aback by the mountains on your right and a forest of mostly Hardwoods surrounding the hole. Since Thompson selected a natural valley for the hole, the impression is almost claustrophobic in contrast, since the previous stretch of holes were wide open. The latter part of the open six presents opportunities to score, so in typical Thompson in form has presented a seemingly insurmountable hole to test their mettle.

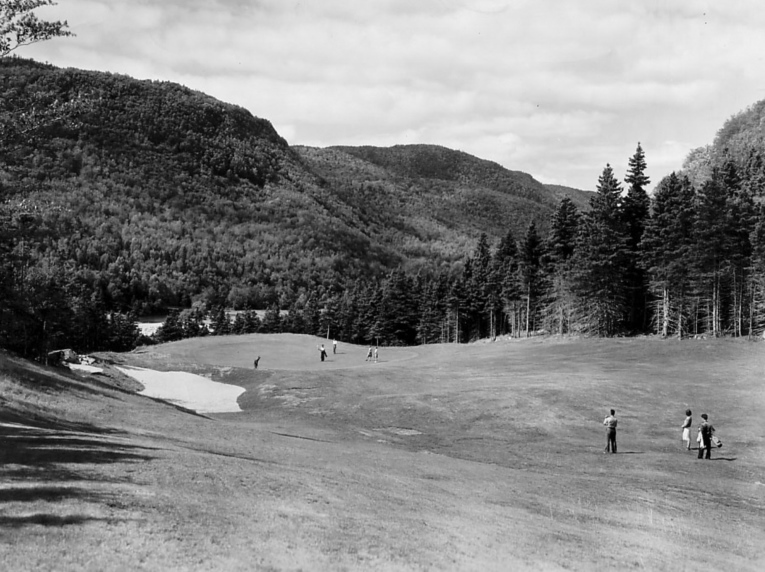

The finish of this two-hole stretch is a breathtaking. From off the back of the 8th green, players can see down into the narrow Clyburn valley framed by the mountains beyond. The initial impression is more tree lined holes to come, but he surprises you at the 9th tee with a wide fairway in the valley below. There is plenty of room off the tee with the shot played into the mountain backdrop and at the turn the hole points directly at Ben Franey in the distance.

Thompson kept the golf fun in the valley, allowing the scenery to dominate this section of holes. This was a breather before taking on the next wildly undulating and much more challenging section to come. The walk from 12 green to the 13th tee is the prettiest walk in golf with players following the bank of the Clyburn right onto the 13th tee. At this point they have exited the valley and up onto the rugged highlands surrounded by stands of conifer. All three holes feature dramatic ocean views all culminating with the 15th played directly at Ingonish Island.

The final transition involves a walk past the pastoral setting of the Catholic Church. The ocean drops out of view and the course returns to the headland. The holes are fairly open and surrounded by more conifers at the periphery. The 18th plays directly toward the highest point on Middle Head and when you reach the green you’re rewarded with a spectacular view of Cape Smokey as your final view.

Whether intended, intuitive or just sheer happenstance, the separation of each unique setting, with long walks between holes, adds to the experience. It slows the player down enough to allow them to enjoy where they are. The breaks emphasize each setting. It makes the round unfold like a series of chapters from a book. Each chapter educates you about that particular geography. And when the chapters are all combined together, it makes for wonderful journey through the local landscape.

The Holes

Hole 1 – Ben Franey

Hole plays toward Ben Franey in the distance. The natural plateau where the green resides was out in a clearing and made a suitable conclusion to the hole. Some of the undulations in the middle of the landing are actually rocks collected during construction covered with topsoil. The back ridge of the green mimics the horizon line of Ben Franey in the background. The most unusual feature found on the hole is a wooden structure built over the large Karst Cavern under the front left bunker.

Hole 2 – Tam O’Shanter

The hole cants around a small hidden valley on the right and then drops dramatically down to a green set on top of ridgeline. This creates a panoramic view of Ingonish Bay, which is one of the most memorable views on the course. The fairway features a series of deep pockets and rumpled undulations. Most of the pockets were deeper and were raised with stumps, rocks and logs. The undulations are largely natural but a few were accentuated by adding extra rocks and covering them with soil. The hole gets its name from the unusual green top hat contours.

Hole 3 – Lochan

The hole plays from the top of the ridgeline, over the saltwater pond, to a green set hard up against a backdrop of dark Spruce. The fairway is just over a foot above sea level and floods regularly. The front of the green will only flood with storms and heavy rains.

Hole 4 – Heich O’ Fash

The hole plays out to a green set on a knoll with Ben Franey looming beyond. The green is reachable, particularly from the left tee, but the closer you get the more dangerous the hole becomes. The combination of deep fronting bunkers, the two ponds on the left and the precipitous drop of the right means you can’t miss the shot played to the green. The mounds at the back of the green were finished to emulate the profile of Ben Franey in the distance. The tee shot used to play over small dunes covered with marram grass, but they were unfortunately used as a source of sand. The large knoll on the right features Karst Formations and an old Portuguese Cemetery on top. They were fishing the area in the late 1800’s and using the mouth of the Clyburn as place of refuge. The ponds left of the green are also Karst Formations and are shockingly deep.

Hole 5 – Canny Slap

The hole was as natural as they come. The green site sits in a bowl just beyond the enormous hollow with only the barn in the way. The early plan shows an alternate tee playing from the right of 4th to the green at 245 yards. The most amusing part of Stanley’s work was the creation of a whimsical bunker formation known as the Dragon and Fireball.

Hole 6 – Muckle Mouth Meg

The elevated tee provides a wonderful panorama of the Clyburn Estuary and mountains beyond. The hole plays down into the flats and begins to slowly curving around the Clyburn Brook finishing hard up against a stand of Spruce on Brook’s edge. There are multiple low points in this fairway that are at one foot sea level. The large mounds behind the green have been essential to avoiding flood damage.

Stanley was very well read enjoying the classics. Only he would be clever/crazy enough take a Robert Browning poem about an unusual and unsightly woman and turn it into the features for a green site. The original score card described his version of the woman including her ability to stick and entire turkey egg in her unusually wide mouth. So with that in mind, using the illustration of what he built, do you see “Muckle Mouth Meg’s face? And the egg?

Hole 7 – Killiecrankie

Stanley found the hole when he crossed the Brook and set foot up the old logging road. The road crossed briefly through open farmland and then ran through the middle of a well-treed the valley. The journey out from the elevated tee, up the broad valley right to the termination at the end was such a natural hole. It was destined to be a great hole from the outset. But his decision to narrowing the landing, add bunkering as you got closer to the green and then build the wildest green on the golf course made this a diabolical hole golfers will never forget.

Hole 8 – Caber’s Toss

The hole harkens back to the courses he visited in Scotland where the tee shot is played blindly over a hill and when the player crests the hill they are rewarded with a beautiful view down to the green. The pitch can be a challenge since the majority of the green falls away from play, but Stanley flipped up the back of the green to make this play like a punchbowl. The problem comes when trying to read your putts.

Hole 9 – Corbie’s Nest

The view from the elevated tee was a wide-open valley. The next shot was between two gills to a green you couldn’t see with Ben Franey directly above. Stanley had to submit a letter to Jim Smart to explain the merits of the 9th hole and why it should stay. He explained that while the green was blind from the landing, all the contours around would feed the ball back towards the putting surface, making it easy to play.

Hole 10 – Cuddy’s Lugg’s

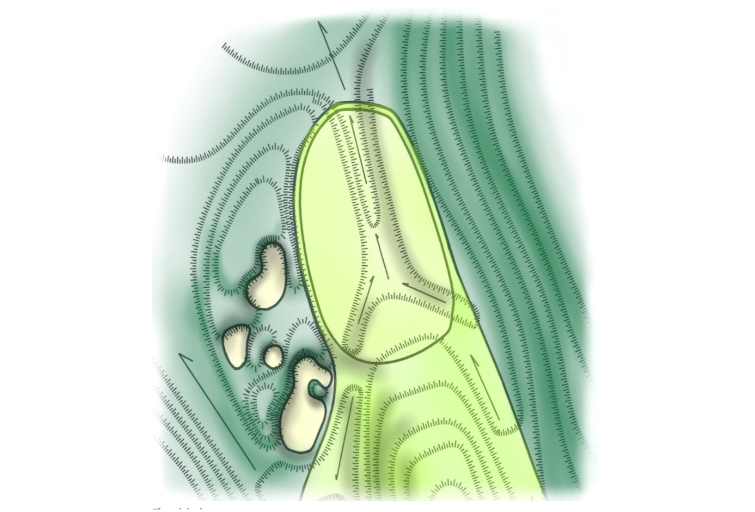

The earliest plan suggested an epic par three to play from an elevated tee, over the river, to a green on the other side. Stanley then changed this to a green on the near side of the river, set on the valley floor, with the Clyburn and mountain as a backdrop. Robbie suggested moving that green to the opposite side of the river hard up against the mountainside. Stanley maintained he wanted the location he selected. The most entertaining aspect of what Stanley built was the two bunkers that were made to look like Donkey’s ears framing the green.

Hole 11 – Bonnie Burn

This was originally a par four played from the existing tees on the other side of the brook. The tee shot was wide open with nothing to fear. Originally, the green was planned to be set hard up against a secondary channel of the brook. But when the green was being built, Stanley shifted the location forward to accommodate a new back tee for the 12th hole. There is a beautiful waterfall back right of the green worth going to see after a rain.

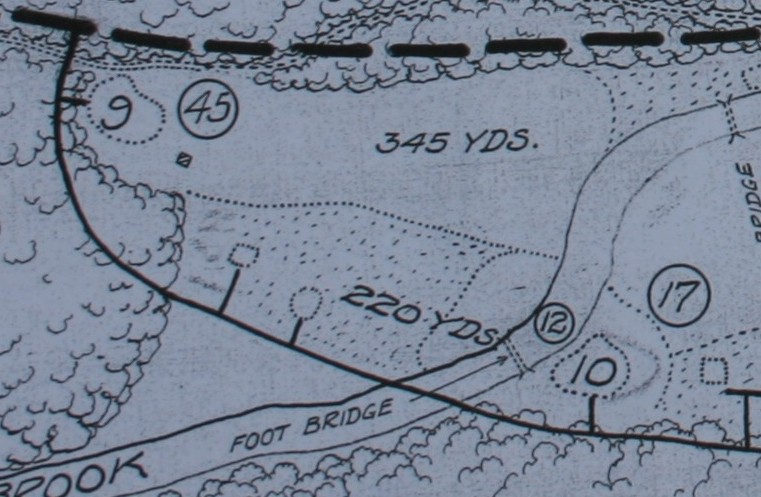

Hole 12 – Cleaugh

The hole was designed to play from the island, back over the brook and up to the base of the rocky cliff. Thompson designed it as a shorter hole but added a much longer tee to ensure he would end up with at least one very long par three on his course.

Hole 13 – Laird

The hole was a short par five. The valley, as Thompson saw it, had only a single ancient apple tree. It would have been easy to envision this hole, but not the location of the green. This is one of Stanley’s greatest golf holes because he made the unusual choice of placing the green directly behind a very prominent knoll. The second shot is all about how you are going to deal with this landform. Since there were no trees on the left hillside by the green, the player had the option of playing well left for a better view into the green. This is the only green that has been rebuilt. The original green was 18” lower and featured an upside down “Y” shaped valley through the middle of the green where the water exited out the back.

Hole 14 – Haugh

The right half of the hole was wide open and he would have been able to follow the hole up to the green site at the end of the valley. The left side was lower and needed to be cleared over to the sharp ridge for additional room to play. The rocks from the cleared area were accumulated and dumped in fairway, covered with topsoil, to create additional ridges in the landing area. The view back from where you exited the green was one of the best on the property.

Hole 15 – Tattie Bogle

While the wild rollercoaster of a fairway is as impressive as anything at Highlands, most people are even more enamoured with the long view out to Ingonish Island. It’s here where Thompson knew he was in competition with his surroundings. To deal with this he surrounded the green with elaborate bunkering and added back mounding to hide the road. He needed enough drama and character to take your eye off the view long and appreciate what he had built.

Hole 16 – Sair Fecht

Thompson was smart to envision this as a very short par five where the player’s ambitions would remove any thoughts about the grade they were now transitioning to. He accomplished this by having a wide landing, no bunkers, and the green clearly within reach of the long player. All you had to do was avoid the fairway moguls the size of cars and buses and you were all set. I had originally thought the entire contour was natural, but it turns out some of the undulations are more of the rocks collected, dumped in place and covered with topsoil.

Hole 17 – Dowie Den

There valley was wide open and being farmed. He likely stood where the tees are now and saw the natural amphitheatre on the far side. The green was cut into the hill, the front raised and the hole was then well bunkered for dramatic effect.

Hole 18 – Hame Noo

Stanley took the players to a small knoll, had them play down into a gentle valley and then back up to a second knoll. Beyond the green in the distance was the highest point on Middle Head to act as a backdrop. The sea was not in view from the tee, but was on your left at the landing and finally on your right at on 18th green. This was the very first view of Cape Smokey.

Afterword

When the course and park officially were opened on Canada Day (July 1, 1941) Canada was at war. Stanley Thompson attended the ceremony. 18 holes remained open for play for 1941, but beginning in 1942 the Long Loop and the two-year-old Keltic Lodge had to be closed due to shortages and a lack of visitors. Bert Donovan and a handful of employees did the best they could to keep the remaining nine in play, but the conditioning slowly deteriorated. The 18-hole course and Keltic Lodge were eventually re-opened in 1946 was the assistance of the federal government.

I was lucky to play the course in 1981 and it was an important childhood memory to me. When I finally returned in 2003, I was appalled at what the course had become. It was over-grown with trees, multiple greens had turf loss, and architect Graham Cooke had inexplicably changed the original bunkering and added the most intrusive cart path system I had ever seen during a renovation in the late 1990s. But I wasn’t the only one frustrated by what I saw. The golf media began to criticize Parks Canada pointing out their responsibility to preserve and protect all history including the golf course.

In 2006 the Historic Sites and Monument Board of Canada recognized Stanley Thompson as a person of National Historical Significance. The combination of Mark Sajatovich, Ken Donovan, and Graham Hudson managed to make this designation come about. This in turn opened up a dialogue about whether Cape Breton Highlands was a place of historical importance.

The pressure caused Parks Canada to concede that the golf course deserved more attention. Hudson began a process to restore where I was eventually brought in. Our common goal was a restoration, no adaptions, no alterations, the quirky bits too. The only exception was that we were going remove a couple of backdrops for additional sunlight to save those greens. It took a while to get Parks Canada on board with tree removal, since the Regional Environmentalist had prohibited any significant removals for decades. But after reading an article on the preservation of cultural landscapes I took a stab and presented the idea of restoring this cultural landscape. I presented the entire history and Parks Canada were supportive a few (reasonable) environmental conditions attached. Now the problem was funding the restoration.

On September 3rd, 2010, Hurricane Earl made landfall bringing minor flooding to the Clyburn Valley. Then on September 21st, Hurricane Igor came through bringing close to seven inches of rain. The Clyburn Valley is defined as a flash valley, meaning everything rushes to the river which gets wildly overloaded producing a very high peak flow (flash flood). The river left its banks and took the most direct route down the valley, right across the 10th and through the middle of the 11th hole. This covered the 11th fairway a foot or more of gravel and sand from start of the hole to green. Graham Hudson being an enterprising thinker accessed an emergency fund to repair the damage. He combined all his existing resources and new capitol to clean up the fairways (6th being the other) and rebuild the flood damaged bunkers. The rebuild felt remarkably close to the build with almost everything done by hand. This included cutting and laying sod from on site. But it was the most enjoyable two years of my career.

George Knudson called Cape Breton Highlands the Cypress Point of Canada. Stanley Thompson called it his “mountains and ocean course.” No matter what expropriation and the recent privatisation say about land ownership, in my mind this course still belongs to the Ingonish Community and to the people of Canada. It is a place of National Historical Significance.

THE END

Ian would like to offer a special thanks to Joe Robinson, Ken Donovan and Geoff Cornish for sharing what they know about the course and its’ history.>>>next>>>